La incidencia del ictus isquémico en el adulto joven está aumentando globalmente, no siendo infrecuente en nuestro territorio. Este se encuentra asociado a la presencia factores de riesgo vascular tradicionales. Sin embargo, poca es la información disponible en cuanto a su pronóstico a diferencia de otros grupos etarios. El objetivo del presente trabajo es determinar la mortalidad, tanto a corto como a largo plazo, y la recurrencia a largo plazo del ictus isquémico en pacientes adultos jóvenes en Aragón, conformando el primer estudio de esta naturaleza en Spain, y de los pocos que aborda el tema en Europa.

Material y métodosEstudio multicéntrico, observacional, retrospectivo de todos los pacientes entre 18 y 50 años que ingresaron por un evento isquémico cerebrovascular en cualquier hospital de Aragón entre 2005–2015. El seguimiento de la muestra se hizo hasta el 31 de marzo de 2021. Se recogió la mortalidad, causas de muerte y recurrencia de eventos cerebrovasculares, estratificando la muestra en base al sexo y grupo etario de los pacientes. Para determinar los factores asociados a mortalidad y recurrencia se usaron modelos de regresión logística y de Cox.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 721 pacientes (697 con seguimiento a largo plazo). La mortalidad fue de 3,3% en los primeros 30 días. La mortalidad y la recurrencia a largo plazo fue de 9,2% y 11,9% en una mediana de 10,1 años de seguimiento. La causa de muerte más frecuente a corto plazo fue la neurovascular y a largo plazo la neoplásica. Tener una NIHSS > 15 se asoció a una mayor mortalidad a corto plazo. La hipertensión arterial, diabetes mellitus, consumo excesivo de alcohol, fibrilación auricular y la enfermedad vascular periférica estuvieron asociadas con la de largo plazo. El antecedente de ictus previo, diabetes mellitus y los ictus de etiología aterotrombótica estuvieron asociados con un mayor riesgo acumulado de recurrencia.

ConclusionesLa mortalidad y recurrencia de ictus isquémico en adultos jóvenes en Aragón, aunque menor a la descrita por otros estudios, no es en absoluto despreciable y se encuentran asociadas a la presencia de factores de riesgo vascular tradicionales.

The incidence of ischemic stroke in young adults is increasing worldwide, and it is not uncommon in our region. It is associated with the presence of traditional vascular risk factors. However, there is little information about its prognosis, unlike other age groups. The objective of this study is to determine mortality, both in the short and long term follow-up, and the long-term follow-up recurrence of ischemic stroke in young adult patients in Aragon, making up the first study of this kind in Spain, and one of the few that addresses this issue in Europe.

MethodsMulticenter, observational, retrospective study of all patients between 18 and 50 years old who were admitted for an ischemic stroke in any hospital in Aragon between 2005−2015. The follow-up was carried out until March 31, 2021. Mortality, causes of death and recurrence of cerebrovascular events were collected, stratifying the sample based on the sex and age group of the patients. Logistic and Cox regression models were used to determine the factors associated with mortality and recurrence.

Results721 patients were included (697 with long-term follow-up). Mortality was 3.3% in the first 30 days. Long-term mortality and recurrence was 9.2% and 11.9% at a median of 10.1 years of follow-up. The most frequent cause of death in the short term was of Neurovascular origin and in the long term was cancer. Having a NIHSS > 15 was associated with higher short-term mortality. Arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, excessive alcohol consumption, atrial fibrillation and peripheral vascular disease were associated with long-term mortality. A history of previous stroke, diabetes mellitus, and atherothrombotic aetiology were associated with a higher cumulative risk of stroke recurrence.

ConclusionsMortality and recurrence of ischemic stroke in young adults in Aragon, although lower than that described by other studies, is by no means negligible and is associated with the presence of traditional vascular risk factors.

Stroke is the third leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Although it most frequently occurs in the eighth decade of life, its incidence and prevalence have increased by 15% and 22%, respectively, among individuals younger than 70 years over the past 20 years.1 In fact, the incidence of ischaemic stroke among young adults is rising worldwide, in contrast with the trend observed in older adults.2 This increase may be due to multiple factors, including improved disease detection or the increased incidence of cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) in this age group.3

Although no specific cut-off age has been established, most studies define young stroke as that occurring in individuals under the age of 50 years.4,5 These individuals are of working age and have a potentially long life expectancy; therefore, in addition to the burden on patients and their families, mortality and disability in individuals with young stroke has a significant socioeconomic impact.

In the Spanish region of Aragon, ischaemic stroke in young adults is not rare, with a mean annual incidence rate of 12.3 cases per 100 000 population. This type of stroke is associated with presence of at least one classic CVRF, and in a significant number of cases the aetiology remains undetermined.3

The purpose of this study is to determine both short- and long-term mortality, as well as long-term recurrence rates of ischaemic stroke in young adults in Aragon. This is the first study of this kind to be conducted in Spain, and one of the few in other European countries, none of which have focused on the Mediterranean region.2,6–13

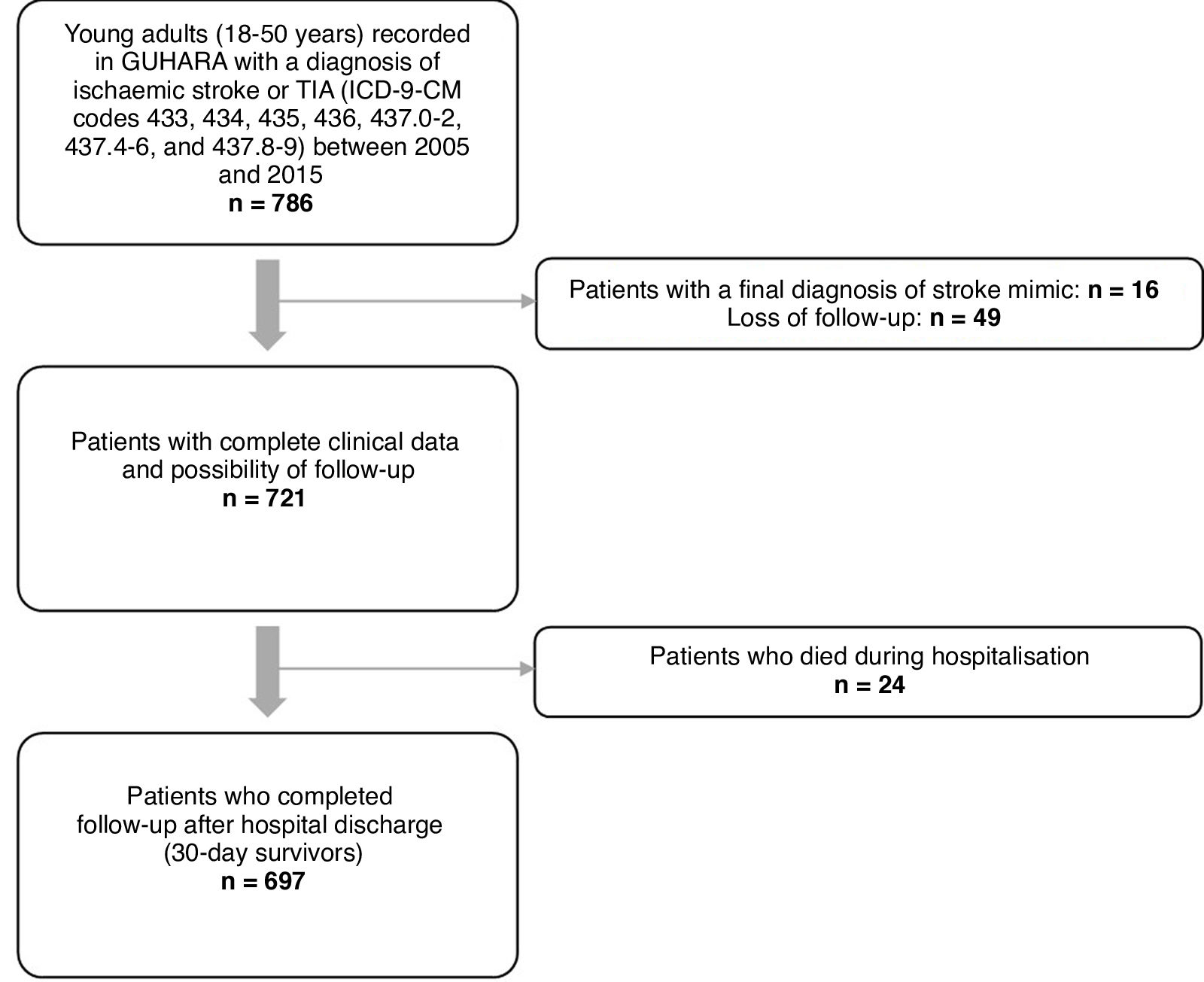

Material and methodsWe conducted a multicentre, retrospective, observational study, gathering data from the neurology departments of all hospitals within the Health Service of Aragon. We identified all patients aged 18 to 50 years who were admitted to any of these hospitals with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) (ICD-9-CM codes 433, 434, 435, 436, 437.0-2, 437.4-6, and 437.8-9) between January 2005 and December 2015. We excluded patients with a discharge diagnosis of venous sinus thrombosis; ischaemic cerebrovascular events secondary to head trauma, strangulation, or complications of subarachnoid haemorrhage; and ischaemic stroke related to surgery, catheterisation, or angiography procedures. Fig. 1 presents the patient selection process.

The following data were gathered from patients’ medical histories: demographic variables, CVRFs (arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, atrial fibrillation, obesity, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, history of ischaemic stroke, history of coronary artery disease, history of peripheral vascular disease), type of ischaemic stroke according to the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project (OCSP) and Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classifications, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score at admission (for patients diagnosed with ischaemic stroke only), whether the patient received reperfusion therapy, and whether antiplatelets or oral anticoagulants were prescribed at discharge.

Patients were followed up until 31 March 2021. Follow-up was divided into 2 periods to assess short- and long-term mortality, considering that the 2 periods have specific characteristics. In accordance with previous studies, short-term mortality was defined as death within 30 days of stroke.14,15 To determine long-term stroke recurrence, we recorded the number of hospital readmissions due to ischaemic stroke in patients who survived the first 30 days after the event.

The variables analysed during long-term follow-up were stratified by sex and age group; by age, patients were split into groups of those aged 18–40 vs 41–50 years, given the high prevalence of CVRFs among ischaemic stroke patients aged 41–50 years in Aragon, as reported in a previous study by our research group.4

For the descriptive analysis, qualitative variables are expressed as frequencies or percentages. Quantitative variables are expressed as measures of central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion (standard deviation or quartiles 1 and 3 [Q1–Q3]), depending on whether data followed a normal distribution.

For the inferential analysis, statistical significance was set at P < .05; we used the chi-square test and the Fisher exact test to compare proportions for qualitative variables, and the t test or ANOVA to compare means when one of the variables was quantitative (Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test for non–normally distributed data).

Multivariate regression models were built using logistic regression or Cox proportional-hazards regression methods. Survival analysis used the Kaplan-Meier method to calculate the cumulative risks of mortality and stroke recurrence in patients who survived the first 30 days after stroke. The log-rank test was used to compare survival curves between groups (sex, age group, number of CVRFs, and aetiology), with P values <.05 being considered statistically significant.

Graphs were created with Microsoft Excel 2010 (version 14.0) and statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (version 21.0).

Our study protocol was approved in April 2016 by the Stroke Care Programme of the region of Aragon and the regional research ethics committee.

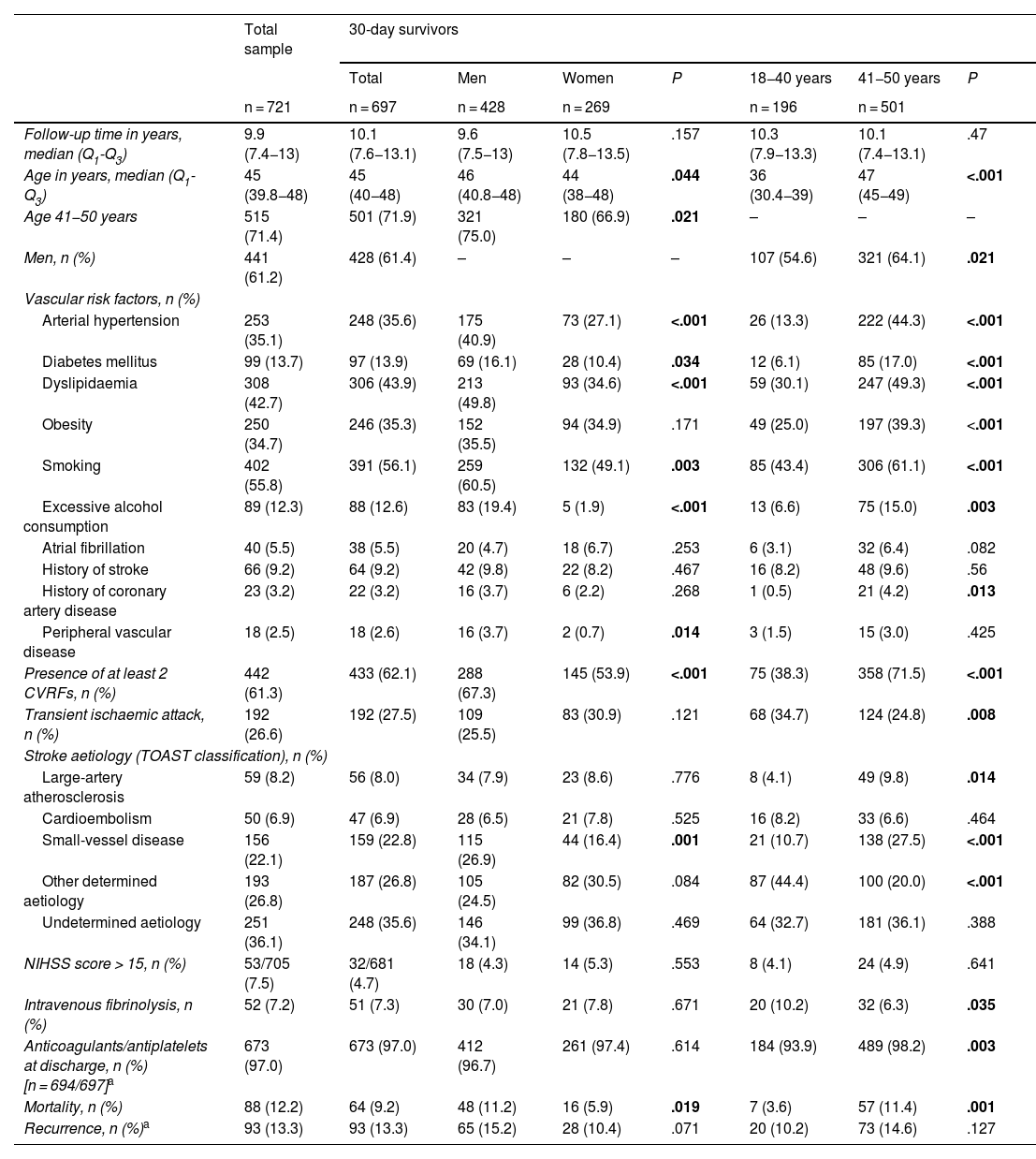

ResultsWe identified 786 patients aged 18 to 50 years who were admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke or TIA between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2015. Of these, 721 patients met the inclusion criteria (61.2% men; median age, 45 years [Q1–Q3: 39.8–48]). At the time of the initial event, 71.4% were 41-50 years old, and 61.3% presented at least 2 CVRFs. Median follow-up time among patients who survived the first 30 days after stroke (n = 697) was 10.1 years (Q1–Q3: 7.6–13.1). Table 1 summarises the demographic and clinical characteristics of our sample.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the total sample and of patients who survived the first 30 days after stroke, by sex and age group.

| Total sample | 30-day survivors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Men | Women | P | 18−40 years | 41−50 years | P | ||

| n = 721 | n = 697 | n = 428 | n = 269 | n = 196 | n = 501 | |||

| Follow-up time in years, median (Q1-Q3) | 9.9 (7.4−13) | 10.1 (7.6−13.1) | 9.6 (7.5−13) | 10.5 (7.8−13.5) | .157 | 10.3 (7.9−13.3) | 10.1 (7.4−13.1) | .47 |

| Age in years, median (Q1-Q3) | 45 (39.8−48) | 45 (40−48) | 46 (40.8−48) | 44 (38−48) | .044 | 36 (30.4−39) | 47 (45−49) | <.001 |

| Age 41−50 years | 515 (71.4) | 501 (71.9) | 321 (75.0) | 180 (66.9) | .021 | – | – | – |

| Men, n (%) | 441 (61.2) | 428 (61.4) | – | – | – | 107 (54.6) | 321 (64.1) | .021 |

| Vascular risk factors, n (%) | ||||||||

| Arterial hypertension | 253 (35.1) | 248 (35.6) | 175 (40.9) | 73 (27.1) | <.001 | 26 (13.3) | 222 (44.3) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 99 (13.7) | 97 (13.9) | 69 (16.1) | 28 (10.4) | .034 | 12 (6.1) | 85 (17.0) | <.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 308 (42.7) | 306 (43.9) | 213 (49.8) | 93 (34.6) | <.001 | 59 (30.1) | 247 (49.3) | <.001 |

| Obesity | 250 (34.7) | 246 (35.3) | 152 (35.5) | 94 (34.9) | .171 | 49 (25.0) | 197 (39.3) | <.001 |

| Smoking | 402 (55.8) | 391 (56.1) | 259 (60.5) | 132 (49.1) | .003 | 85 (43.4) | 306 (61.1) | <.001 |

| Excessive alcohol consumption | 89 (12.3) | 88 (12.6) | 83 (19.4) | 5 (1.9) | <.001 | 13 (6.6) | 75 (15.0) | .003 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 40 (5.5) | 38 (5.5) | 20 (4.7) | 18 (6.7) | .253 | 6 (3.1) | 32 (6.4) | .082 |

| History of stroke | 66 (9.2) | 64 (9.2) | 42 (9.8) | 22 (8.2) | .467 | 16 (8.2) | 48 (9.6) | .56 |

| History of coronary artery disease | 23 (3.2) | 22 (3.2) | 16 (3.7) | 6 (2.2) | .268 | 1 (0.5) | 21 (4.2) | .013 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 18 (2.5) | 18 (2.6) | 16 (3.7) | 2 (0.7) | .014 | 3 (1.5) | 15 (3.0) | .425 |

| Presence of at least 2 CVRFs, n (%) | 442 (61.3) | 433 (62.1) | 288 (67.3) | 145 (53.9) | <.001 | 75 (38.3) | 358 (71.5) | <.001 |

| Transient ischaemic attack, n (%) | 192 (26.6) | 192 (27.5) | 109 (25.5) | 83 (30.9) | .121 | 68 (34.7) | 124 (24.8) | .008 |

| Stroke aetiology (TOAST classification), n (%) | ||||||||

| Large-artery atherosclerosis | 59 (8.2) | 56 (8.0) | 34 (7.9) | 23 (8.6) | .776 | 8 (4.1) | 49 (9.8) | .014 |

| Cardioembolism | 50 (6.9) | 47 (6.9) | 28 (6.5) | 21 (7.8) | .525 | 16 (8.2) | 33 (6.6) | .464 |

| Small-vessel disease | 156 (22.1) | 159 (22.8) | 115 (26.9) | 44 (16.4) | .001 | 21 (10.7) | 138 (27.5) | <.001 |

| Other determined aetiology | 193 (26.8) | 187 (26.8) | 105 (24.5) | 82 (30.5) | .084 | 87 (44.4) | 100 (20.0) | <.001 |

| Undetermined aetiology | 251 (36.1) | 248 (35.6) | 146 (34.1) | 99 (36.8) | .469 | 64 (32.7) | 181 (36.1) | .388 |

| NIHSS score > 15, n (%) | 53/705 (7.5) | 32/681 (4.7) | 18 (4.3) | 14 (5.3) | .553 | 8 (4.1) | 24 (4.9) | .641 |

| Intravenous fibrinolysis, n (%) | 52 (7.2) | 51 (7.3) | 30 (7.0) | 21 (7.8) | .671 | 20 (10.2) | 32 (6.3) | .035 |

| Anticoagulants/antiplatelets at discharge, n (%) [n = 694/697]a | 673 (97.0) | 673 (97.0) | 412 (96.7) | 261 (97.4) | .614 | 184 (93.9) | 489 (98.2) | .003 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 88 (12.2) | 64 (9.2) | 48 (11.2) | 16 (5.9) | .019 | 7 (3.6) | 57 (11.4) | .001 |

| Recurrence, n (%)a | 93 (13.3) | 93 (13.3) | 65 (15.2) | 28 (10.4) | .071 | 20 (10.2) | 73 (14.6) | .127 |

CVRF: cardiovascular risk factors; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; Q1–Q3: quartiles 1 and 3; TOAST: Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment.

The Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project classification was used only in patients with ischaemic stroke.

Statistically significant differences are shown in bold.

In the group of 30-day survivors, a significant difference was observed in the distribution of CVRFs between men and women, as well as between individuals aged ≤40 and > 40 years. Regarding stroke aetiology, large-artery atherosclerosis and small-vessel disease were the most frequent subtypes in patients aged 41 to 5 years (9.8%, vs 4.1% in the younger age group [P = .014], and 27.5% vs 10.7% [P < .001], respectively). Small-vessel disease was also more frequent in men than in women (26.9% vs 16.4% [P = .001]). Strokes due to other determined causes were more frequent in the younger age group (44.4% vs 20% [P < .001]).

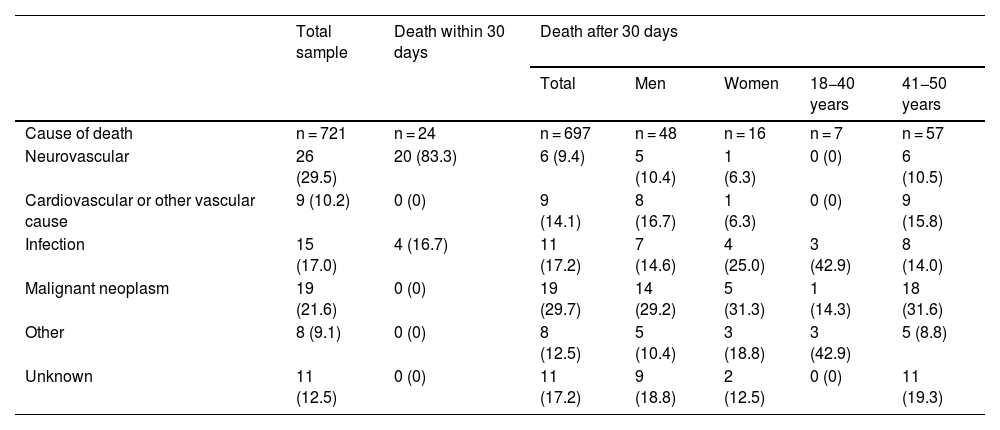

Short-term and long-term mortalityEighty-eight patients died during follow-up: 24 (3.3%) within 30 days of stroke (during hospitalisation in all cases), and the remaining 64 over the long-term follow-up period (9.2% of the 697 30-day survivors). In the total sample, mortality rates were higher in men (13.8%, vs 9.6% in women) and in patients aged 41-50 years (13.8%, vs 8.3% in the younger age group). However, these differences were statistically significant only among 30-day survivors (11.2% vs 5.9% [P = .019] for sex, and 3.6% vs 11.4% [P = .001] for age group). Table 2 describes the causes of death in our sample, by survival time, sex, and age group. Neurovascular causes were the most frequent within 30 days of ischaemic stroke (83.3%), whereas malignancies (29.7%) and infections (17.2%) were the most prevalent during the long-term follow-up period.

Causes of mortality in the total sample, in patients who died within 30 days after the cerebrovascular event, and in 30-day survivors, by sex and age group.

| Total sample | Death within 30 days | Death after 30 days | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Men | Women | 18−40 years | 41−50 years | |||

| Cause of death | n = 721 | n = 24 | n = 697 | n = 48 | n = 16 | n = 7 | n = 57 |

| Neurovascular | 26 (29.5) | 20 (83.3) | 6 (9.4) | 5 (10.4) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 6 (10.5) |

| Cardiovascular or other vascular cause | 9 (10.2) | 0 (0) | 9 (14.1) | 8 (16.7) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 9 (15.8) |

| Infection | 15 (17.0) | 4 (16.7) | 11 (17.2) | 7 (14.6) | 4 (25.0) | 3 (42.9) | 8 (14.0) |

| Malignant neoplasm | 19 (21.6) | 0 (0) | 19 (29.7) | 14 (29.2) | 5 (31.3) | 1 (14.3) | 18 (31.6) |

| Other | 8 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 8 (12.5) | 5 (10.4) | 3 (18.8) | 3 (42.9) | 5 (8.8) |

| Unknown | 11 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 11 (17.2) | 9 (18.8) | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 11 (19.3) |

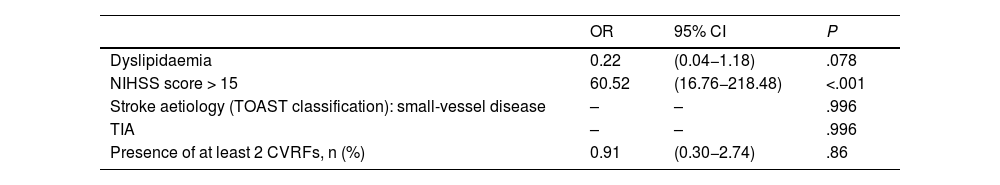

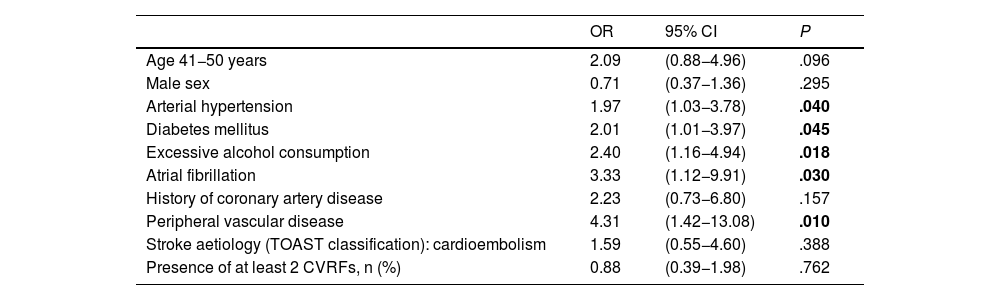

In the multivariate analysis, only moderate-to-severe stroke at admission (NIHSS score >15) was found to be significantly associated with higher mortality within 30 days of stroke (OR = 60.5; 95% CI, 16.8–218.5) (Table 3). None of the patients admitted with a diagnosis of TIA or lacunar ischaemic stroke died during the short-term follow-up period. Arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, excessive alcohol consumption, atrial fibrillation, and peripheral vascular disease were found to be significantly associated with long-term mortality in our sample (Table 4).

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with mortality within 30 days after ischaemic stroke.

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dyslipidaemia | 0.22 | (0.04−1.18) | .078 |

| NIHSS score > 15 | 60.52 | (16.76−218.48) | <.001 |

| Stroke aetiology (TOAST classification): small-vessel disease | – | – | .996 |

| TIA | – | – | .996 |

| Presence of at least 2 CVRFs, n (%) | 0.91 | (0.30−2.74) | .86 |

CI: confidence interval; CVRF: cardiovascular risk factors; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; OR: odds ratio; TIA: transient ischaemic attack; TOAST: Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with mortality beyond 30 days after ischaemic stroke.

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age 41−50 years | 2.09 | (0.88−4.96) | .096 |

| Male sex | 0.71 | (0.37−1.36) | .295 |

| Arterial hypertension | 1.97 | (1.03−3.78) | .040 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.01 | (1.01−3.97) | .045 |

| Excessive alcohol consumption | 2.40 | (1.16−4.94) | .018 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3.33 | (1.12−9.91) | .030 |

| History of coronary artery disease | 2.23 | (0.73−6.80) | .157 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 4.31 | (1.42−13.08) | .010 |

| Stroke aetiology (TOAST classification): cardioembolism | 1.59 | (0.55−4.60) | .388 |

| Presence of at least 2 CVRFs, n (%) | 0.88 | (0.39−1.98) | .762 |

CI: confidence interval; CVRF: cardiovascular risk factors; OR: odds ratio; TOAST: Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment.

Statistically significant differences are shown in bold.

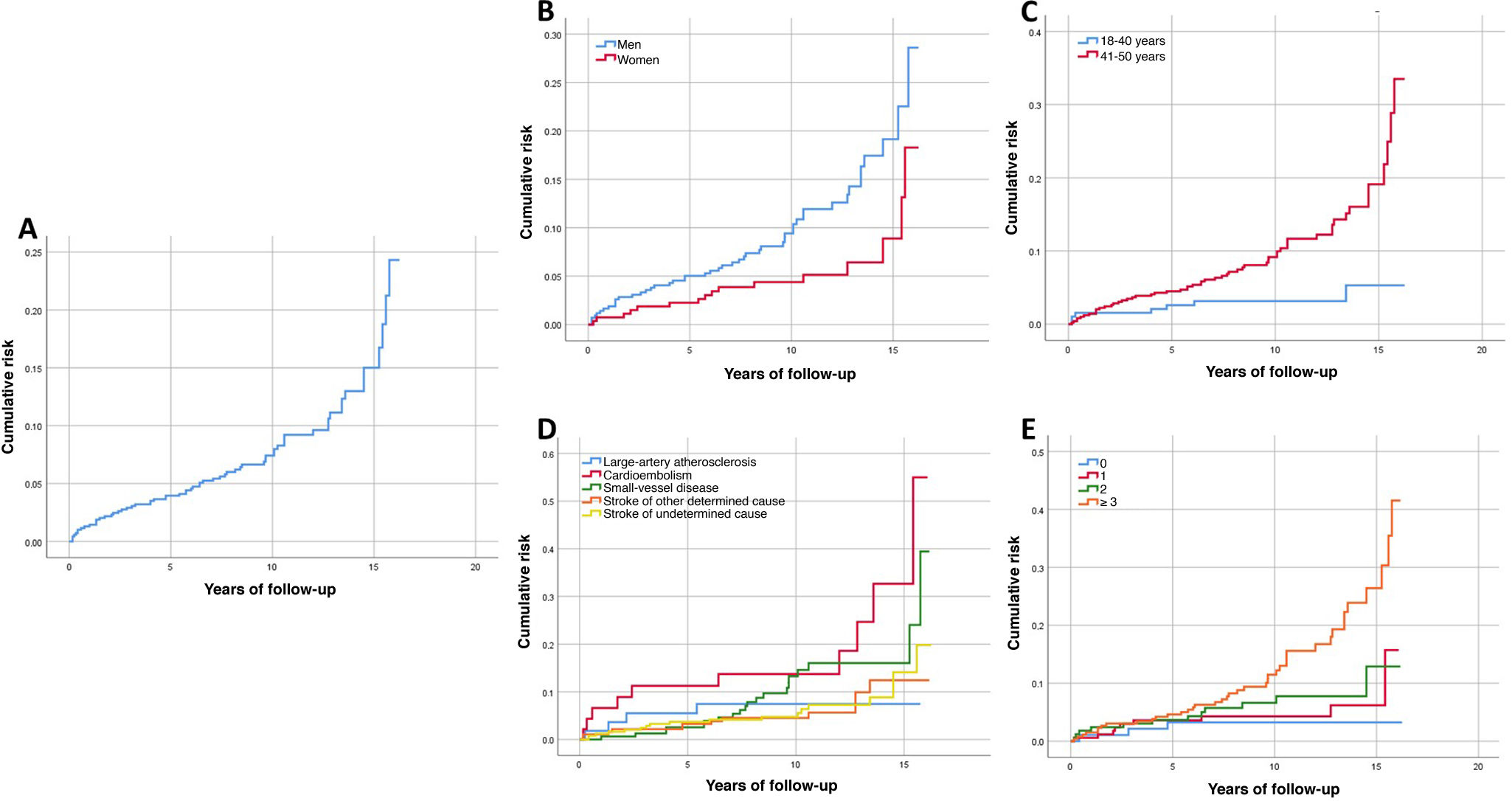

In 30-day survivors, the cumulative mortality risk at the end of follow-up was 24.3% (Fig. 2 A), with a significantly higher rate in men (P = .013) and in patients aged 41-50 years (P = .001) (Fig. 2 B and C). Significant differences were also observed in the cumulative mortality curves based on stroke aetiology (P = .033) and number of CVRFs (P = .001) (Fig. 2 D and E). In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, the CVRFs arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, excessive alcohol consumption, atrial fibrillation, and peripheral vascular disease were significantly associated with greater cumulative mortality risk during the long-term follow-up period (Supplementary Material: Table A.1).

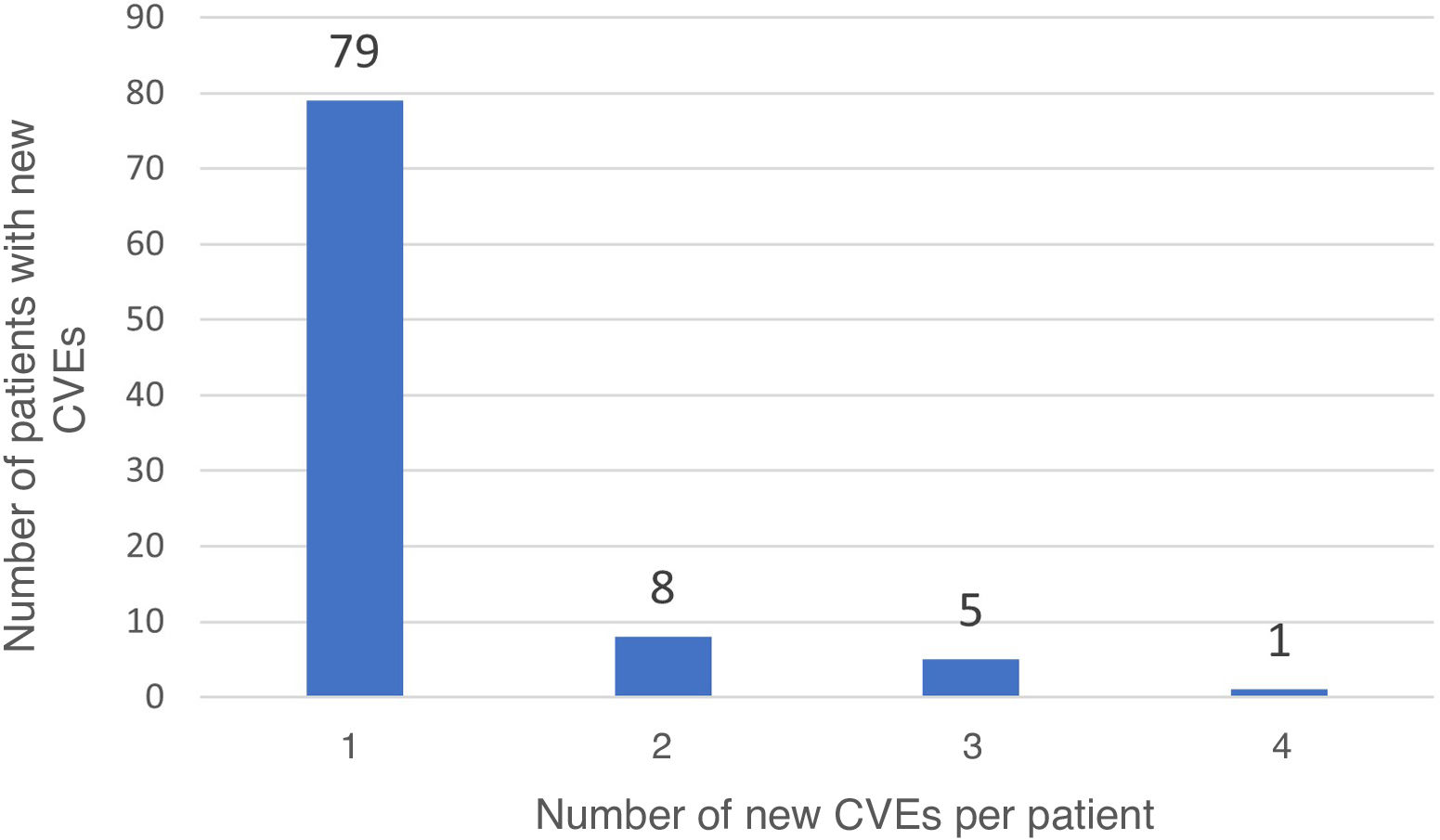

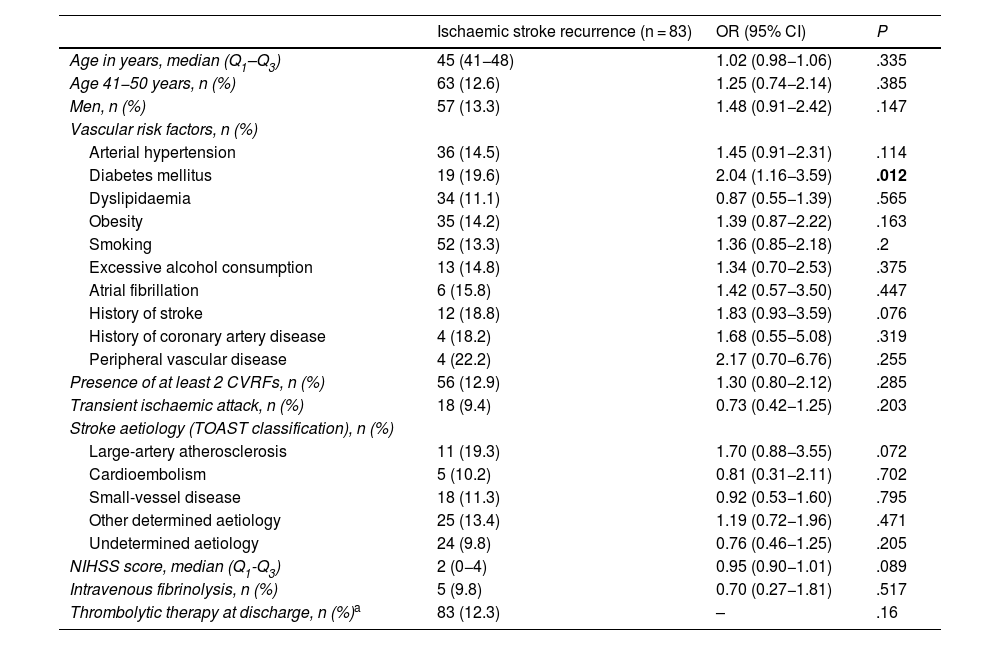

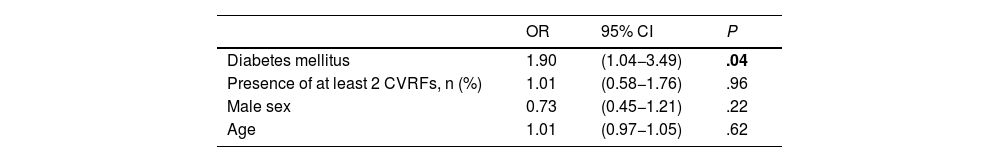

Long-term recurrenceOf the 697 patients who survived the first 30 days after stroke, 93 (13.3%) presented recurrent stroke, amounting to 114 recurrences. Fourteen patients with recurrent stroke (16.9%) presented more than one recurrence during follow-up (Fig. 3). In 11 patients, recurrent stroke was haemorrhagic. One patient presented an ischaemic stroke recurrence, followed by a haemorrhagic stroke. Table 5 presents the bivariate analysis of variables associated with ischaemic stroke recurrence during follow-up in our sample. Only history of diabetes mellitus was significantly associated with greater risk of ischaemic stroke recurrence in the long-term; this association remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, and presence of 2 or more CVRFs in the multivariate analysis (OR = 1.9; 95% CI, 1.04–3.49; P = .04) (Table 6).

Recurrence in patients who survived the first 30 days after ischaemic stroke.

| Ischaemic stroke recurrence (n = 83) | OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, median (Q1–Q3) | 45 (41−48) | 1.02 (0.98−1.06) | .335 |

| Age 41−50 years, n (%) | 63 (12.6) | 1.25 (0.74−2.14) | .385 |

| Men, n (%) | 57 (13.3) | 1.48 (0.91−2.42) | .147 |

| Vascular risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 36 (14.5) | 1.45 (0.91−2.31) | .114 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 19 (19.6) | 2.04 (1.16−3.59) | .012 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 34 (11.1) | 0.87 (0.55−1.39) | .565 |

| Obesity | 35 (14.2) | 1.39 (0.87−2.22) | .163 |

| Smoking | 52 (13.3) | 1.36 (0.85−2.18) | .2 |

| Excessive alcohol consumption | 13 (14.8) | 1.34 (0.70−2.53) | .375 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6 (15.8) | 1.42 (0.57−3.50) | .447 |

| History of stroke | 12 (18.8) | 1.83 (0.93−3.59) | .076 |

| History of coronary artery disease | 4 (18.2) | 1.68 (0.55−5.08) | .319 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 4 (22.2) | 2.17 (0.70−6.76) | .255 |

| Presence of at least 2 CVRFs, n (%) | 56 (12.9) | 1.30 (0.80−2.12) | .285 |

| Transient ischaemic attack, n (%) | 18 (9.4) | 0.73 (0.42−1.25) | .203 |

| Stroke aetiology (TOAST classification), n (%) | |||

| Large-artery atherosclerosis | 11 (19.3) | 1.70 (0.88−3.55) | .072 |

| Cardioembolism | 5 (10.2) | 0.81 (0.31−2.11) | .702 |

| Small-vessel disease | 18 (11.3) | 0.92 (0.53−1.60) | .795 |

| Other determined aetiology | 25 (13.4) | 1.19 (0.72−1.96) | .471 |

| Undetermined aetiology | 24 (9.8) | 0.76 (0.46−1.25) | .205 |

| NIHSS score, median (Q1-Q3) | 2 (0−4) | 0.95 (0.90−1.01) | .089 |

| Intravenous fibrinolysis, n (%) | 5 (9.8) | 0.70 (0.27−1.81) | .517 |

| Thrombolytic therapy at discharge, n (%)a | 83 (12.3) | – | .16 |

CVRF: cardiovascular risk factors; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; OR: odds ratio; Q1–Q3: quartiles 1 and 3; TOAST: Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment.

Statistically significant differences are shown in bold.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with ischaemic stroke recurrence in patients who survived the first 30 days after the event.

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.90 | (1.04−3.49) | .04 |

| Presence of at least 2 CVRFs, n (%) | 1.01 | (0.58−1.76) | .96 |

| Male sex | 0.73 | (0.45−1.21) | .22 |

| Age | 1.01 | (0.97−1.05) | .62 |

CI: confidence interval; CVRF: cardiovascular risk factors; OR: odds ratio.

Statistically significant differences are shown in bold.

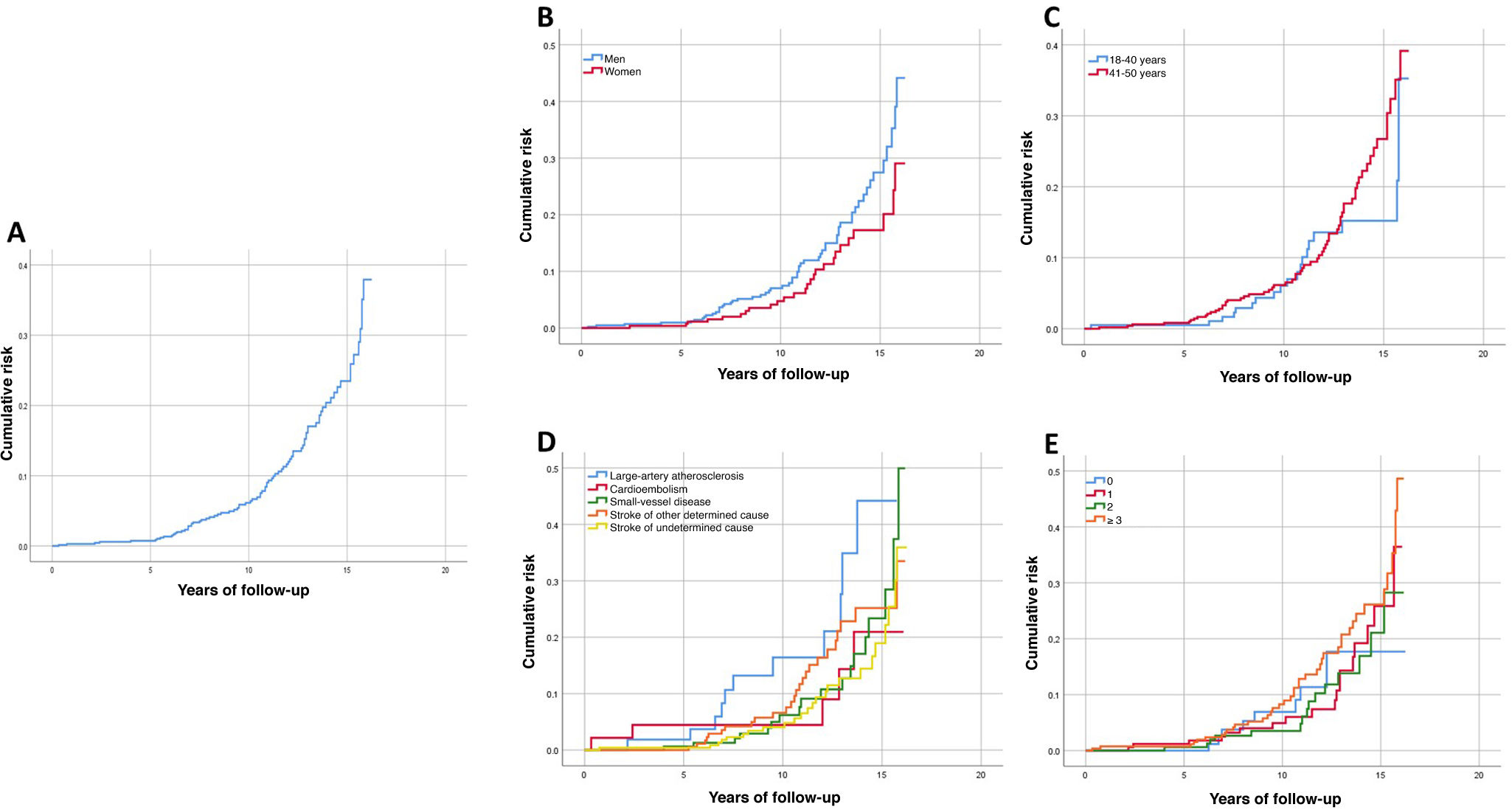

Cumulative recurrence risk at the end of follow-up was 47.7% (Fig. 4 A), with a non-significant trend toward higher risk in men and in some stroke aetiologies (P = .076 and P = .058, respectively) (Fig. 4 B and D). No significant differences were observed in cumulative recurrence curves based on the number of CVRFs or age group (Fig. 4 C and E). In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, the CVRFs diabetes mellitus and history of stroke, and large-artery atherosclerotic aetiology were significantly associated with greater cumulative recurrence risk during long-term follow-up (Supplementary Material: Table A.2).

DiscussionThe worldwide impact of stroke has been studied extensively.1 In Europe, stroke affects an estimated 1.1 million people per year, causing around 440 000 deaths annually.16,17 It is unsurprising that it remains a health priority in the European Union, as well as the subject of a joint initiative led by the European Stroke Organisation (ESO) and the Stroke Alliance for Europe (SAFE).18,19

The incidence of stroke among young adults has increased over the past 2 decades. This population group is of working age and has a potentially long life expectancy. As a result of stroke, approximately 50% of these patients present cognitive alterations, 55% experience mood disorders, and nearly half are unable to return to their previous employment20–22; this entails a greater socioeconomic burden than with older adults, both for the healthcare system and for the patients’ families. Young adults with stroke are estimated to experience a loss of 9.21 quality-adjusted life years as compared to the age-matched general population.23

The definition of “young adult” varies across studies; this should be taken into account when interpreting the results of these studies.2,3,24,25 In our study, “young adult” was defined as individuals aged 18 to 50 years, as this is the most widely used definition and the one with the largest body of epidemiological data in our setting.4

Our sample’s baseline characteristics are similar to those of a previous epidemiological study of ischaemic stroke in young adults in Aragon.4 Aside from this study, no other recent study has systematically analysed these data across an entire Spanish region. Arboix et al.26 described the clinical characteristics of 280 patients younger than 55 years who were consecutively admitted to Hospital Universitario del Sagrat Cor in Barcelona between 1986 and 2009 due to stroke. As in that study, the most prevalent CVRF in our sample was smoking (55.8%), and the most frequent aetiologies of ischaemic stroke were small-vessel disease (22.1%) and other determined cause (26.8%); this has also been reported in other countries.3,11

Our study is the first to analyse ischaemic stroke mortality and recurrence in young adults in Spain and in the Mediterranean region, and one of the very few European studies to have focused on this topic. In Spain, a study completed in 2001 analysed the long-term prognosis of ischaemic stroke in young adults. However, the sample was drawn from a single centre, and therefore included only a small proportion of all patients attended due to ischaemic stroke in that region.13

Like previous studies, our study distinguished between mortality within 30 days of the event and mortality during the rest of the follow-up period (long-term follow-up).2 The reason for this distinction is the reported evidence of different demographic and clinical profiles in patients with short-term and long-term mortality14,15; this was also observed in our sample (Supplementary Material: Table A.3).

In our sample, the 30-day mortality rate was 3.3%, and the long-term mortality rate was 9.2%. This short-term mortality rate is consistent with those reported in previous studies.2,7,8,12 The lower long-term mortality rate observed in our sample6,12,25 may be due to the inclusion of patients with TIA, which is associated with lower mortality rates than established ischaemic stroke.12 Another factor that may have played a role is the lower prevalence in our sample of variables associated with increased mortality, as compared to other studies.2 Finally, most studies report cumulative mortality risk; this measure is different from mortality, and was higher in our study (24.3% at the end of follow-up).

Regarding factors associated with mortality, only moderate-to-severe stroke at admission (NIHSS score > 15) was associated with increased risk of mortality within 30 days of stroke. During the long-term follow-up, however, an association was also observed with such CVRFs as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, excessive alcohol consumption, atrial fibrillation, and peripheral vascular disease. These associations have also been reported in other studies.14,15 Patients with severe ischaemic stroke present risk of malignant cerebral infarction or such complications as aspiration pneumonia and pulmonary embolism, which can contribute to the risk of early mortality. However, after the first 30 days, it is not stroke severity but rather other factors, such as classic CVRFs, that increase mortality in these patients.

Similarly, we also observed significant differences between the causes of death within 30 days of stroke (neurovascular diseases and infections) and during long-term follow-up (malignancies in nearly one-third of cases). Furthermore, deaths due to neurovascular, cardiovascular, or other vascular causes accounted for 23.5% of all deaths occurring during long-term follow-up, which may be linked to the high prevalence of classic CVRFs in our sample. On the other hand, the prevalence of cancer in young adults with ischaemic stroke may reach 7.7% after a median follow-up period of 10 years27; this may explain the role of cancer as a major cause of long-term mortality in these patients.

In our study, the survival curves for cumulative long-term mortality risk presented a similar pattern to those reported by Schneider et al.2 and Maaijwee et al.25 However, the differences observed in mortality rates between sexes and age groups during long-term follow-up are probably influenced by the higher prevalence of CVRFs among men over the age of 40 years, as CVRFs continued to display an independent association with mortality and cumulative mortality risk in the multivariate analysis, unlike age and sex, which lost statistical significance. In fact, the cumulative long-term mortality curve for patients with ≥ 3 CVRFs is clearly different from that of patients with no CVRFs; however, the multivariate Cox regression analysis found that the presence of CVRFs, but not the number of CVRFs, was significantly associated with increased cumulative mortality risk. This may indicate that mortality is influenced differently by each CVRF, or even by the different interactions between them, rather than simply by the accumulation of CVRFs.

The rate of recurrence of ischaemic stroke during the follow-up period was 11.9%. This rate is lower than those reported by other studies, such as the one by Varona et al.13; however, that study was conducted in a single centre and included a very long recruitment period (1974–2001), during a time when the management of stroke and CVRFs was probably very different to that of our study period. Very few similar studies have been conducted with which we may compare our results. We found a significant association between diabetes mellitus and greater likelihood of recurrence during the follow-up period; this is in line with findings from the previously mentioned study, which also reported an association with other CVRFs, large-artery atherosclerosis, and age over 35 years.

Regarding cumulative recurrence risk, Putaala et al.,28 in a study with 5 years of follow-up, found a statistically significant association with diabetes mellitus, age, large-artery atherosclerosis, and history of TIA. In our study, a significant association was only observed with history of stroke and large-artery atherosclerosis.

The weaker association found in our study between CVRFs and ischaemic stroke recurrence, compared to mortality, may be explained by a number of factors, including the fact that CVRFs have an impact not only on stroke mortality but also on mortality from other cardiovascular diseases, and the definition of recurrence used in our study. We defined recurrent ischaemic stroke as any cerebrovascular event requiring hospitalisation, as recorded in our health information system; this may have overlooked cases of TIA that were managed at the emergency department without the need for hospital admission.

In line with similar studies,2,7,14,15 our results underscore the impact of classic CVRFs on the long-term prognosis of young adults with ischaemic stroke in terms of both mortality and recurrence. The prevalence of CVRFs among young adults is increasing worldwide, which has an impact on the prognosis of a wide range of diseases, including stroke.29 The American Heart Association (AHA) recently added sleep health as a new component of cardiovascular health to its traditional 7-item list.30 Primary and secondary stroke prevention strategies should be specifically developed for this patient population.

Finally, regarding QALY loss among young adults, future studies should not only assess the risk of mortality and recurrence in the long term, but also functional status after stroke. Therefore, in these patients, functional assessment tools beyond the modified Rankin Scale should be used to analyse such other factors as self-perceived health or social and work performance.

LimitationsThe main limitation of this study is its retrospective, observational design. Such CVRFs as obesity, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption may be underrepresented, and cases diagnosed as stroke of undetermined aetiology may be due to an incomplete evaluation.

Furthermore, we did not control for such follow-up variables as treatment adherence or whether CVRFs observed at admission were controlled during follow-up. Likewise, we were unable to determine whether new CVRFs appeared in patients with no CVRFs at the time of stroke diagnosis.

As mentioned in the discussion section, the inclusion of patients with TIA in our study may have resulted in lower mortality and recurrence rates than in other studies: although in our region, only patients with TIA presenting high risk of recurrence are admitted to hospital (these are the cases included in our sample), we cannot rule out the possibility of stroke mimics among these cases.

Finally, the recruitment period pre-dates the routine implementation of endovascular treatment for ischaemic stroke in our region; therefore, current mortality rates may differ from those reported in this study.

ConclusionYoung stroke mortality and recurrence rates in Aragon, though lower than those reported in other studies, are by no means negligible. As stroke mortality and recurrence are associated with classic CVRFs, significant efforts should be made to strengthen healthcare policies aimed at reducing the prevalence of these factors in our setting. It is often said that our health in old age is built during our youth. However, in the light of findings from studies like our own, we should not forget that what we aim to prevent may not be so distant. CVRF prevention and promotion of a healthy lifestyle should be pursued throughout life, and healthcare systems and professionals, as key stakeholders, should play an active role in ensuring that this is the case.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.