Today, the increasing frequency and complexity of life-threatening emergency care interventions related to acute neurological syndromes in hospital emergency departments,1 and the evidence of the impact on prognosis, care quality, and cost reduction of the intervention of a neurologist in such diseases as stroke, firmly establish the need for an on-call neurologist to be physically present at the hospital 24hours a day.2–4 In fact, despite the heterogeneity of on-call neurology models in the different autonomous communities, more and more Spanish hospitals are filling this gap.5

The longitudinal study by Ramírez-Moreno et al.6 of in-hospital neurology consultations in a university hospital confirmed that the emergency department ordered the most consults, most frequently for patients exhibiting loss of consciousness and epileptic seizures. Together with studies by other authors, this study underlines the need for early consultations with a neurologist in diseases other than acute stroke that are frequently encountered by emergency departments.7,8 Previous studies analysing management of epileptic seizures in emergency departments have stressed that neurologists are needed in the emergency department to confirm and start treatment. Good communication with emergency clinicians and primary care doctors will result in continuity of care and prevent diagnostic and management errors in this patient group.9

To date, the circumstances pushing emergency department doctors to order neurological consults for patients with seizures remain unknown. Also to be determined is whether the patient would undergo the same intervention whether or not the neurologist was consulted, and whether short-term outcomes are affected by in-hospital neurology consults.

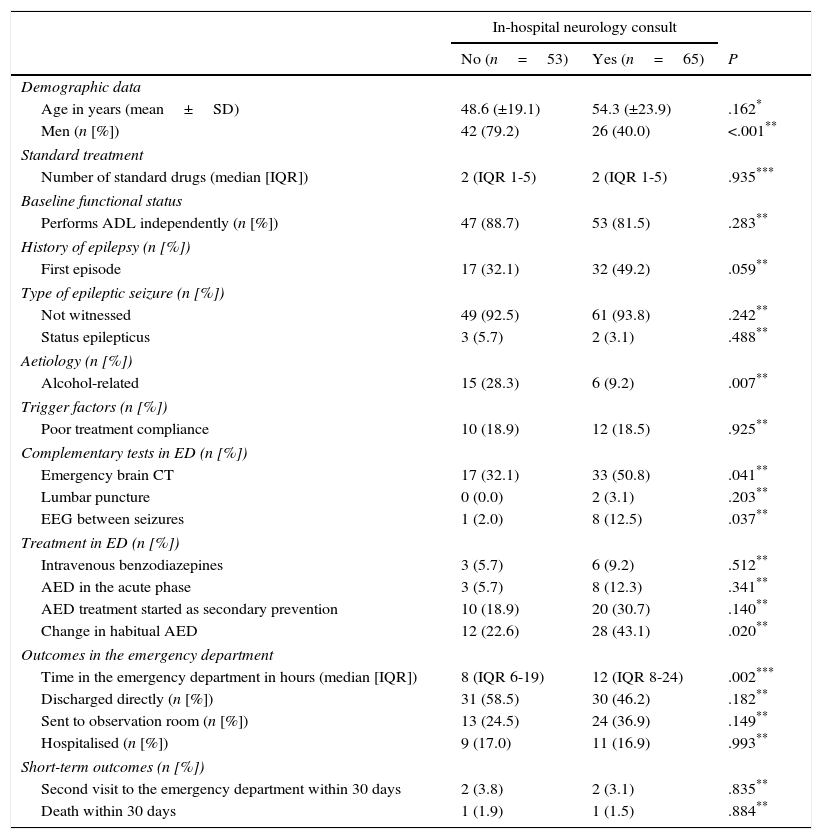

We designed a descriptive study aiming to define the profile of patients attended in emergency departments for convulsions or epilepsy and whose management included an emergency neurology consult. We also intended to ascertain any differences in management and short-term outcomes when emergency doctors call for a consult. This descriptive study followed a retrospective cohort including all patients aged 16 and older whose main reason for consultation was epileptic seizure. Patients were attended in the emergency department of a tertiary referral university hospital between 1 September and 31 December 2011. Demographic, clinical, and management data, and the final destination of the patient after the emergency department visit were collected. We also gathered follow-up data 30 days after the initial episode motivating the emergency visit using the electronic medical records pertaining to the emergency department, the hospital, and the Madrid healthcare system (Horus). The sample was divided into 2 groups for the analysis according to whether or not the emergency department had requested a neurology consult, and it consisted of 118 patients (0.3%) of the total of 37573 seen in the emergency department. The on-call neurologist was consulted in 65 cases (55.1%). Regarding patient profiles, emergency in-hospital consultations with a neurologist tend to be more frequent in possible first epileptic seizures (49.2% vs 32.1%; P=.059), but less frequent in men than in women (40% vs 79.2%; P<.001) or when alcohol is suspected to be the possible trigger or aetiological factor (9.2% vs 28.3%; P=.007). Patients assessed by the neurologist were more likely to undergo emergency brain computed tomography (CT) (50.8% vs 32.1%; P=.041), electroencephalogram (EEG) between seizures (12.5% vs 2.0%; P=.037), and changing the usual antiepileptic drug (AED) (43.1% vs 22.6%; P=.020). In terms of the patient's final destination and short-term outcomes, statistically significant differences were only found in the median time of stay in the emergency department (12h, IQR: 8-24 vs 8h, IQR: 6-19; P=.002) (Table 1).

Analysis of patients attended in the emergency department due to epileptic seizure broken down by presence or absence of an emergency consult.

| In-hospital neurology consult | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=53) | Yes (n=65) | P | |

| Demographic data | |||

| Age in years (mean±SD) | 48.6 (±19.1) | 54.3 (±23.9) | .162* |

| Men (n [%]) | 42 (79.2) | 26 (40.0) | <.001** |

| Standard treatment | |||

| Number of standard drugs (median [IQR]) | 2 (IQR 1-5) | 2 (IQR 1-5) | .935*** |

| Baseline functional status | |||

| Performs ADL independently (n [%]) | 47 (88.7) | 53 (81.5) | .283** |

| History of epilepsy (n [%]) | |||

| First episode | 17 (32.1) | 32 (49.2) | .059** |

| Type of epileptic seizure (n [%]) | |||

| Not witnessed | 49 (92.5) | 61 (93.8) | .242** |

| Status epilepticus | 3 (5.7) | 2 (3.1) | .488** |

| Aetiology (n [%]) | |||

| Alcohol-related | 15 (28.3) | 6 (9.2) | .007** |

| Trigger factors (n [%]) | |||

| Poor treatment compliance | 10 (18.9) | 12 (18.5) | .925** |

| Complementary tests in ED (n [%]) | |||

| Emergency brain CT | 17 (32.1) | 33 (50.8) | .041** |

| Lumbar puncture | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) | .203** |

| EEG between seizures | 1 (2.0) | 8 (12.5) | .037** |

| Treatment in ED (n [%]) | |||

| Intravenous benzodiazepines | 3 (5.7) | 6 (9.2) | .512** |

| AED in the acute phase | 3 (5.7) | 8 (12.3) | .341** |

| AED treatment started as secondary prevention | 10 (18.9) | 20 (30.7) | .140** |

| Change in habitual AED | 12 (22.6) | 28 (43.1) | .020** |

| Outcomes in the emergency department | |||

| Time in the emergency department in hours (median [IQR]) | 8 (IQR 6-19) | 12 (IQR 8-24) | .002*** |

| Discharged directly (n [%]) | 31 (58.5) | 30 (46.2) | .182** |

| Sent to observation room (n [%]) | 13 (24.5) | 24 (36.9) | .149** |

| Hospitalised (n [%]) | 9 (17.0) | 11 (16.9) | .993** |

| Short-term outcomes (n [%]) | |||

| Second visit to the emergency department within 30 days | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.1) | .835** |

| Death within 30 days | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.5) | .884** |

ADL: activities of daily life; SD: standard deviation; ED: emergency department; EEG: electroencephalogram; AED: antiepileptic drug; N: total number; IQR: interquartile range; CT: computed tomography.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide data on the profile, emergency management, and short-term outcomes of patients with epileptic seizures attended in emergency departments when doctors call for an emergency neurology consult. This study shows that intervention by a neurologist, when available on-call 24hours, is more likely to be requested by the emergency department doctor for patients with a first epileptic seizure that is not suspected to be linked to alcohol consumption. It also shows that intervention by a neurologist is associated with higher numbers of certain emergency complementary tests, such as brain CT and EEG between seizures, and with changes in AED in patients with a history of epilepsy who present due to epileptic seizure. This study's main limitations, in addition to those inherent to the study design, are that it did not include a paediatric population, and the diagnosis of epileptic seizure was not subsequently reassessed by an expert. This is important, since a correct initial diagnosis during emergency care can modify outcomes.10,11

Therefore, considering all the above and drawing from experience with other emergency procedures, we recognise the need to determine which patients seen by the emergency department for epileptic seizure will benefit the most from a consultation with the on-call neurologist. Furthermore, the medical specialties involved in this process must jointly create an action protocol to improve the quality and safety of care for patients with epileptic seizures in Spanish emergency departments.12,13 Tools helping us make decisions for daily clinical practice should also be designed.14

Please cite this article as: Fernández Alonso C, Matias-Guiu JA, Castillo C, Martín-Sánchez FJ. Análisis de las interconsultas al neurólogo de guardia por crisis comicial en un servicio de urgencias. Neurología. 2016;31:572–574.