Spinal cord infarction is a rare entity that accounts for approximately 1.2% of all central nervous system infarctions and explains 5%-8% of cases of acute myelopathy.1 It may be caused by multiple factors, although the most frequent aetiology is atherothrombosis, in the context of invasive vascular procedures or thoracic-abdominal surgeries, during which detached emboli may migrate distally.2

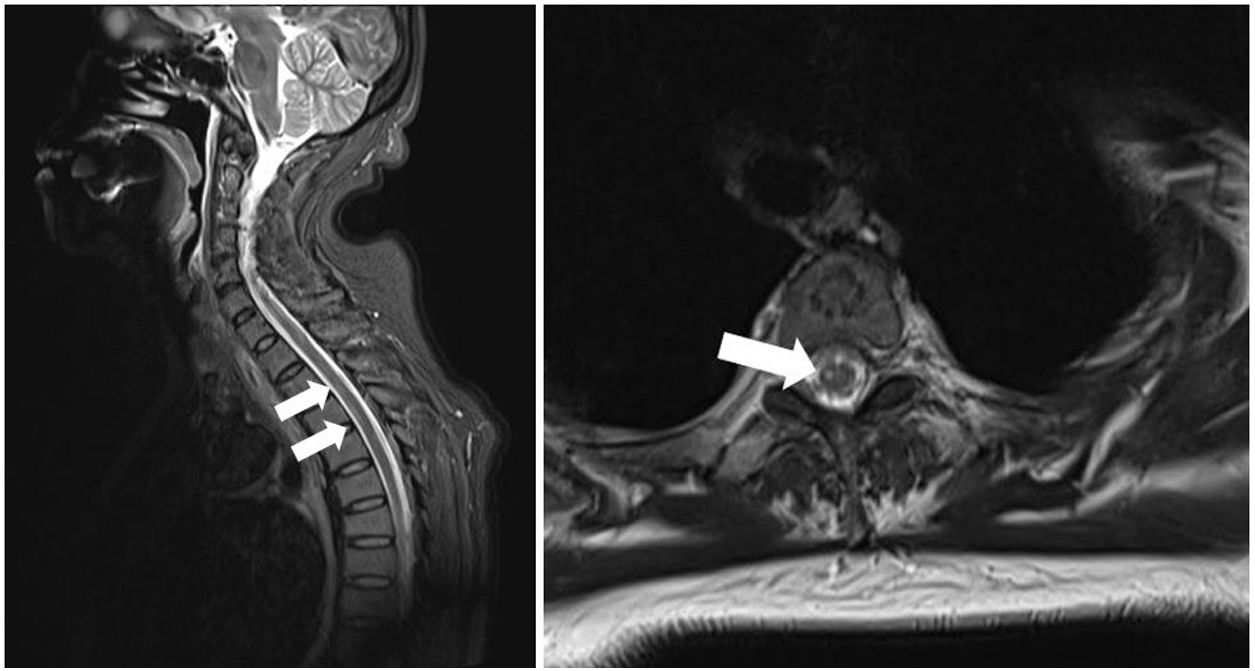

We present the case of a 54-year-old Chinese woman with history of occasional haemoptysis due to a pseudonodular lesion to the right upper lobe and bronchial artery hypertrophy, for which she underwent successful embolisation in 2011. In 2018, she presented another episode of haemoptysis with haemodynamic instability, and underwent emergency bronchial artery embolisation; the procedure was successful. The patient’s general status improved after 2 days at the intensive care unit, but she presented difficulty moving the right leg; this was interpreted as possible postoperative right femoral nerve neurapraxia. The intensive care unit requested a consultation with the neurology department 2 days later due to lack of clinical improvement. The neurological examination revealed an adequate level of consciousness and no alterations in cranial nerve function. The patient presented hypotonia in the right leg: she was only able to move the limb on the horizontal plane and presented 2/5 muscle strength in the right psoas, quadriceps, and hamstrings muscles and 4−/5 in the right tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles. Muscle tone and strength were normal in all other limbs. The patient also presented tactile and thermal hypoaesthesia and hypalgesia in the left side of the body at the T6 sensory level, without reduced vibration sensitivity or alterations in arthrokinetic sensitivity, as well as lower limb hyporeflexia and absent plantar reflex in the right foot. Suspecting acute, incomplete anterior cord syndrome, we performed a spinal cord MRI scan, which revealed T2 and STIR hyperintensities and diffusion restriction in the anterior column of the upper thoracic segments (T2-T7), compatible with recent ischaemic lesions (Figs. 1 and 2).

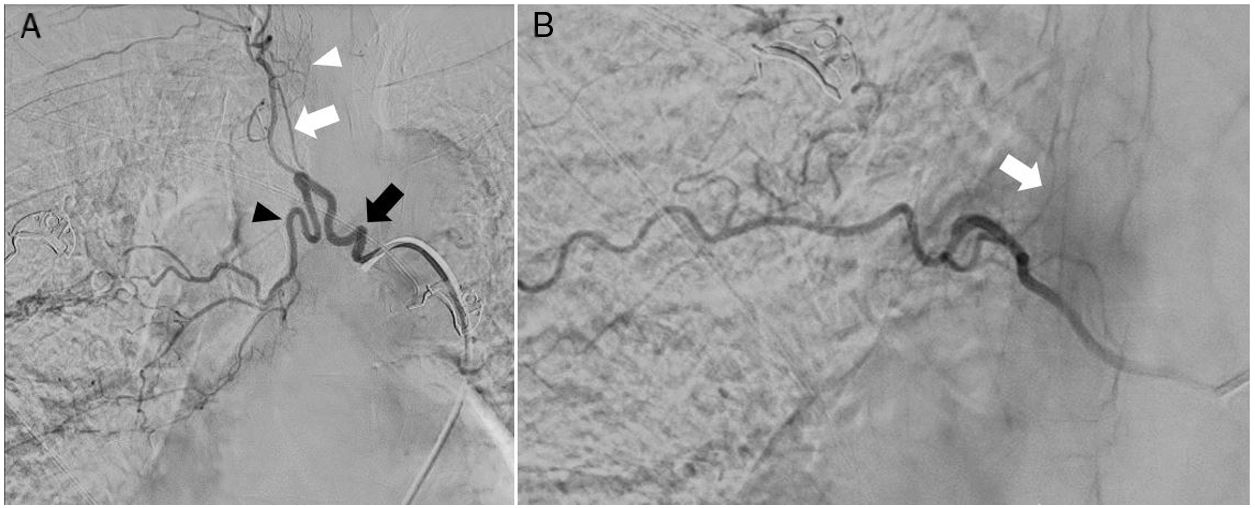

A) Digital subtraction angiography shows the right intercostobronchial trunk (black arrow), feeding a hypertrophic bronchial artery (black arrowhead), and pathological intrapulmonary vascularisation. The intercostobronchial trunk also gives rise to a common trunk for several intercostal arteries (white arrow), which feed several radiculomedullary arteries; the anterior medullary artery is not visible at this level (white arrowhead). B) Right intercostal artery at the T8 level, which gives rise to the radiculomedullary artery that connects with the anterior medullary artery (arrow). No embolisation procedure was performed at this level.

The patient started rehabilitation treatment during hospitalisation, presenting acute urinary retention, which required placement of a urinary catheter, and frequent episodes of orthostatic hypotension associated with profuse sweating; these symptoms are compatible with autonomic dysreflexia. At discharge, the patient was able to walk short distances independently and presented mild right leg paresis with 4/5 muscle strength and tactile hypoaesthesia and hypalgesia in the left side of the body, at the T6 sensory level. After 3 months of outpatient rehabilitation treatment, the patient is independent in the activities of daily living, but considerable autonomic dysfunction persists.

This case is an example of iatrogenic anterior spinal cord infarction following bronchial artery embolisation due to migration of embolisation particles to the spinal arteries. This rare occurrence (very few cases have been reported) constitutes the most severe complication of bronchial artery embolisation, presenting in 1.4%-6.5% of procedures.3

During embolisation, the main risk factor for this complication is presence at the thoracic level of a radiculomedullary artery following the trajectory of the corresponding spinal nerve until reaching the anterior spinal artery. Origin of a radiculomedullary artery as a branch of the bronchial artery, while presenting in only 5% of cases, increases the risk of ischaemic complications; visualisation of this artery during the procedure is an absolute contraindication for bronchial artery embolisation due to the high risk of embolism.4,5 At the thoracic level, the radiculomedullary artery may also originate from a common intercostobronchial trunk or from an intercostal artery. Visualisation of radicular arteries originating from the bronchial artery or intercostal arteries does not constitute an absolute contraindication for embolisation, since they only supply the spinal nerve. However, due to the haemodynamic changes that occur during bronchial artery embolisation, it has been hypothesised that initially undetected radiculomedullary branches may subsequently open, allowing embolic material into the anterior spinal artery, as has previously been reported.6 Several review articles suggest that the size of the embolisation particles may constitute a risk factor; the use of particles larger than 350 μm is therefore recommended.7

During the procedure, we found the bronchial artery in our patient to originate from a common intercostobronchial trunk on the right side; intercostal arteries arising from that trunk gave rise to several radicular arteries. Therefore, we performed selective catheterisation of the bronchial artery, aiming to preserve the intercostal branches and radicular arteries. The embolisation particles used measured 100-300 μm in diameter; migration of embolic material was not observed during the procedure. An intercostal arteriography at the right T7 level revealed a radiculomedullary artery originating from the intercostal artery and connecting with the anterior medullary artery. No embolisation procedure was performed at this level.

No specific evidence-based recommendations have been issued on the treatment of spinal cord infarction. The use of fibrinolysis is limited since the exact time of symptom onset is uncertain on many occasions, leading to diagnostic delays that leave patients outside the treatment window. To date, only isolated cases have been reported of successful fibrinolysis.8

The prognosis of spinal cord infarction is poor: only 11%-46% of patients are able to walk independently after the event.9 The main risk factors for poor functional prognosis include initial severity, female sex, old age, and lack of improvement within 24 hours of symptom onset. Although prognosis is usually poor, functional recovery may occur several months or even years after the lesion, which underscores the importance of early, long-term rehabilitation treatment.

In conclusion, while spinal cord infarction is an infrequent complication of bronchial artery embolisation, physicians should be aware of this entity and be familiar with the associated anatomical and technical risk factors; prevention is essential given the poor long-term functional prognosis and associated morbidity. Long-term rehabilitation treatment may achieve substantial functional improvement, even several months or years after the event.

Please cite this article as: Ramírez Torres M, Lastras Fernández C, Rodríguez Pardo J. Infarto medular anterior tras embolización bronquial. Neurología. 2021;36:248–250.