Cytarabine is an antimetabolite antineoplastic agent indicated mainly as a first-line treatment for acute myeloid leukaemia and as a second- or third-line treatment for lymphomas. At high doses (>48g/m2), it may cause a pancerebellar syndrome characterised by ataxia, dysarthria, and oculomotor alterations.1 However, at a total dose <15g/m2, cytarabine-induced neurotoxicity is extremely rare, with very few published cases in the literature.2,3 We present the first case series of cerebellar toxicity in patients receiving low doses of cytarabine.

Between 2008 and 2013, 4 patients in our hospital developed cerebellar syndrome secondary to treatment with cytarabine. Tables 1 and 2 summarise patients’ baseline characteristics and clinical symptoms, respectively. All patients had lymphoma; they were receiving cytarabine as part of rescue chemotherapy after relapse due to first-line treatment failure. They had all completed at least one cycle of chemotherapy, that meaning that all patients had been in contact with cytarabine but had never manifested any neurotoxic effects. The dose of cytarabine was adjusted to each patient's age: the 2 patients older than 60 (patients 1 and 4) received half doses, whereas the 2 youngest (patients 2 and 3) received the standard dose. None of them had a history of kidney disease but 3 of them had pre-existing liver disease.

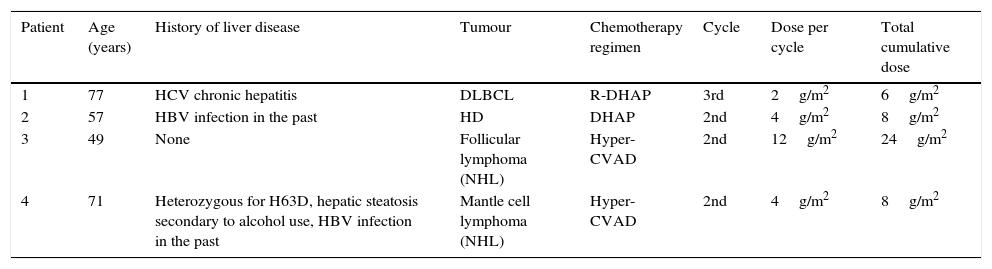

Patient characteristics at baseline.

| Patient | Age (years) | History of liver disease | Tumour | Chemotherapy regimen | Cycle | Dose per cycle | Total cumulative dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 77 | HCV chronic hepatitis | DLBCL | R-DHAP | 3rd | 2g/m2 | 6g/m2 |

| 2 | 57 | HBV infection in the past | HD | DHAP | 2nd | 4g/m2 | 8g/m2 |

| 3 | 49 | None | Follicular lymphoma (NHL) | Hyper-CVAD | 2nd | 12g/m2 | 24g/m2 |

| 4 | 71 | Heterozygous for H63D, hepatic steatosis secondary to alcohol use, HBV infection in the past | Mantle cell lymphoma (NHL) | Hyper-CVAD | 2nd | 4g/m2 | 8g/m2 |

HD, Hodgkin disease; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus. R-DHAP: chemotherapy regimen including cisplatin, cytarabine (2g/m2/12h during day 2 of the cycle), dexamethasone, and rituximab. Hyper-CVAD: chemotherapy regimen consisting of 2 cycles; the first one with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone, and the second with methotrexate and cytarabine (3g/m2/12h during days 2 and 3 of the cycle).

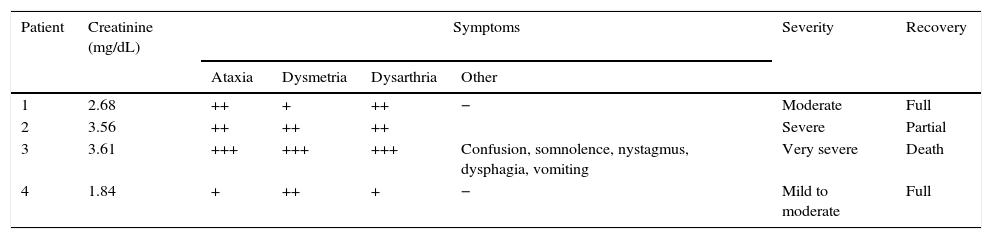

Clinical manifestations.

| Patient | Creatinine (mg/dL) | Symptoms | Severity | Recovery | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ataxia | Dysmetria | Dysarthria | Other | ||||

| 1 | 2.68 | ++ | + | ++ | − | Moderate | Full |

| 2 | 3.56 | ++ | ++ | ++ | Severe | Partial | |

| 3 | 3.61 | +++ | +++ | +++ | Confusion, somnolence, nystagmus, dysphagia, vomiting | Very severe | Death |

| 4 | 1.84 | + | ++ | + | − | Mild to moderate | Full |

Symptoms: –, absent; +, mild; ++, moderate; +++, severe/disabling.

Cerebellar symptoms appeared 3 to 5 days after the first dose of cytarabine was administered, and symptoms were always associated with acute renal failure. This loss of renal function had occurred 48 to 72hours previously and was attributed to either the toxic effects of another chemotherapeutic agent or to tumour lysis syndrome. Symptoms appeared suddenly in all cases and consisted of a pancerebellar syndrome characterised by ataxic gait, bilateral dysmetria, and dysarthria. The most severe of the cases (patient 3) also presented multidirectional nystagmus and a decreased level of consciousness. Symptom severity was directly associated with the degree of renal dysfunction (expressed as the serum creatinine level). Patient 3 was the only one to also present liver dysfunction secondary to drug toxicity.

All patients underwent a thorough aetiological study, including a CSF analysis and a brain MRI scan, which ruled out other possible causes of cerebellar dysfunction (vertebrobasilar stroke, CNS infection, tumour infiltration, or space-occupying lesion). Patients 1 and 4, who had received lower doses of cytarabine due to their advanced age but who at the same time were the ones with milder signs of kidney failure, showed more favourable outcomes, with symptoms resolving in the following 3 to 4 days. Patient 2, who was severely affected, was left with ataxic gait and mild bilateral dysmetria as sequelae. Patient 3, who presented the most severe neurological symptoms of all in addition to liver failure, died in the hospital.

Cerebellar toxicity is a dose-dependent secondary effect of cytarabine; high doses of this drug are therefore linked to the greatest risk of developing this syndrome. Given that cytarabine is mainly eliminated through urinary excretion of its inactive metabolite, age and kidney failure may decrease cytarabine excretion, leading to drug accumulation and neurotoxicity,4 even at standard doses as in our case series. Liver dysfunction has also been described as a risk factor for cerebellar syndrome secondary to cytarabine1; 3 of our 4 patients had a history of liver disease. In addition, some genotypes have been found to increase the likelihood of developing this syndrome, which may explain the considerable inter-individual variability in the toxic response to cytarabine.5 Although symptoms are normally mild and transient, they can also be severe and irreversible,6 as occurred in 2 of our patients. Prevention and early diagnosis are essential for avoiding long-term sequelae or even death. We recommend adjusting the dose to the patient's age, closely monitoring renal function, preventing volume depletion with adequate oral hydration, and treating kidney disease with fluid therapy.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sainz de la Maza Cantero S, Jiménez Martín A, de Felipe Mimbrera A, Corral Corral Í. Toxicidad cerebelosa por citarabina: serie de 4 casos. Neurología. 2016;31:491–492.

This study was presented as an oral communication at the 66th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology.