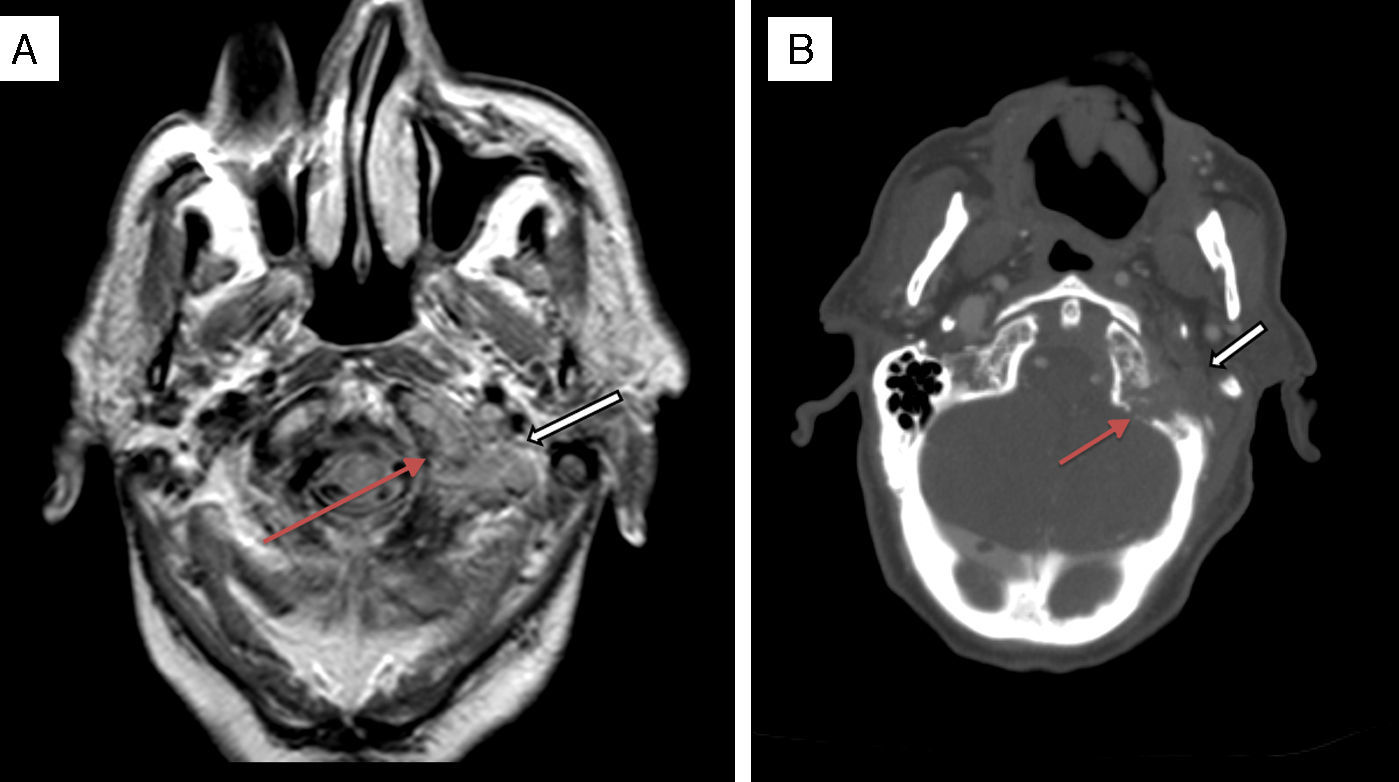

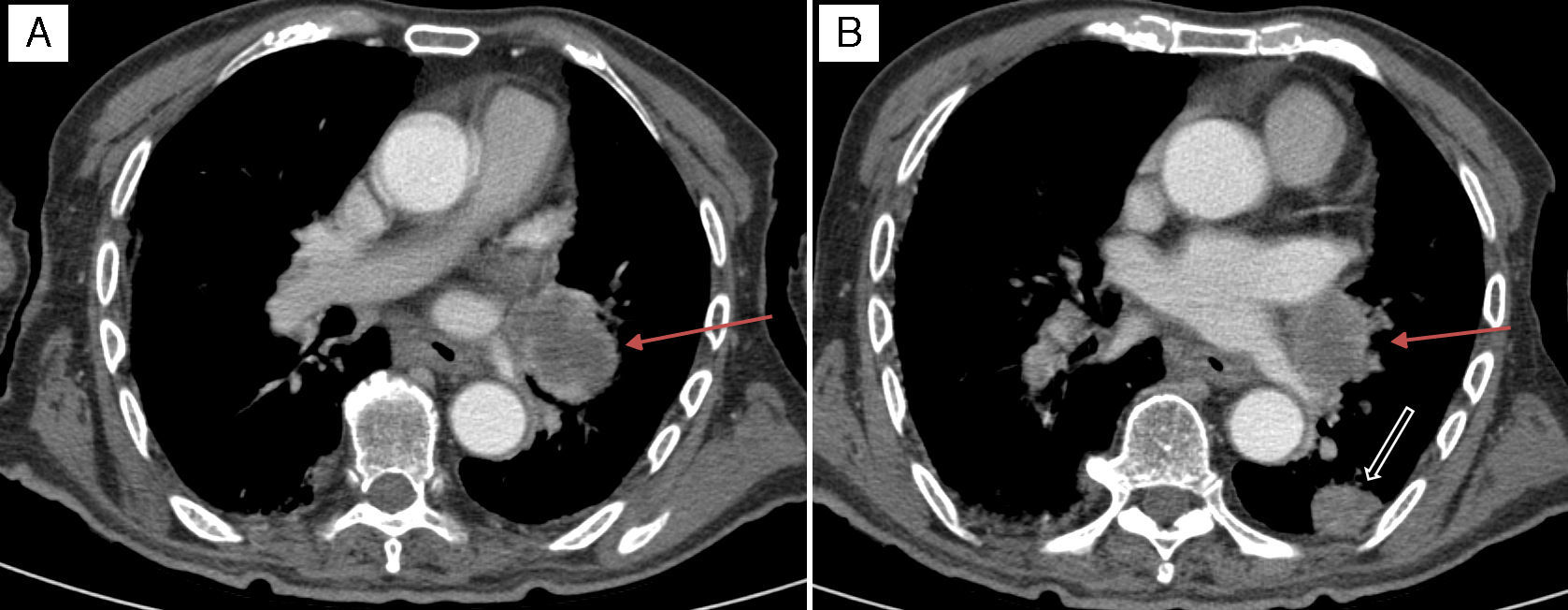

It was with great interest that we read the case of Collet–Sicard syndrome (CSS) described by Gutiérrez Ríos et al.1 and the explanation for the syndrome offered by these researchers. However, we were surprised to note that their literature search only yielded 51 cases of CSS published between 1915 and 2012. We would like to point out that the number of published cases has increased in recent years: a review of post-traumatic cases of CSS published in April 2015 identified 14 cases,2 that is, 4 more cases of post-traumatic CSS than those identified by Gutiérrez Ríos et al. The low number of published cases may be explained by several reasons. The first is the rareness of the associated symptoms and the fact that the syndrome may be mistaken for other similar syndromes affecting nearby topographical locations. As Gutiérrez Ríos et al. state, there are many jugular foramen syndromes and they may exhibit gradual progression. This situation may result in different diagnoses in the same patient depending on the stage of disease progression. Another potential explanation for the low number of cases is the difficulty of diagnosing CSS when multiple cranial nerves are affected. In some cases, involvement of one nerve (for example, the vagus nerve) may mask the involvement of another (for example, the glossopharyngeal nerve); this is more likely to occur when patients are not examined by neurologists. And lastly, as in other diseases, many cases identified in our setting may have not been published. We offer the example of a previously unpublished case of CSS in a 90-year-old man who was attended at our hospital a year ago. Our patient had a history of arterial hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus, and an mRS score of 0 according to our records. He visited the emergency department on 2 occasions due to progressive dysphonia and dysphagia. He was initially diagnosed with left vocal cord paralysis. An outpatient follow-up study including a CT scan of the neck and chest was scheduled to rule out compression of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve. However, our patient returned to the emergency department a few days after his first visit due to intense left-sided headache. On that occasion, he was assessed by neurologists who identified dysarthria and tongue deviation to the left side; all other general and neurological findings were normal. A simple cranial CT scan performed at the emergency department revealed no relevant findings and a chest radiography showed thickening of the left parihilar region. The patient was admitted for a more thorough study. During hospitalisation, his symptoms worsened: he presented marked weakness of the left sternocleidomastoid, deviation of the uvula to the right, left palatal paralysis, and abolished left gag reflex with no sympathetic involvement. All these findings pointed to CSS (involvement of the left IX, X, XI, and XII cranial nerves). A cranial MRI scan (Fig. 1A) revealed a lytic lesion with soft tissue mass in the left occipital condyle which suggested metastasis; the lesion was confirmed by a full-body CT scan (Fig. 1B). The CT scan also revealed a spiculated mass in the left infrahilar region measuring 55mm (Fig. 2A) as well as a solitary pulmonary nodule ipsilateral to the spiculated mass and measuring 20mm (Fig. 2B). Our patient displayed no symptoms of prostate cancer or apparent bone infiltration in the chest or vertebral column. Given our patient's advanced age and the wishes of his family, we ruled out aggressive treatment and opted for palliative care. The patient died a few days later after developing laryngeal stridor and acute respiratory failure. The physicians who last attended him did not request an autopsy.

Axial proton density MRI scan (A) and axial cranial CT scan with intravenous contrast (B) showing an osteolytic lesion with bone destruction in the left condyle and left occipital tubercle (thin arrows) and a soft tissue mass (bold arrows) extending to both sides of the bone, invading the foramen magnum, and extending anteriorly to the tip of the odontoid process. The mass also occupies the jugular foramen and hypoglossal canal, and is in contact with the ipsilateral vertebral artery.

Axial CT scan of the chest with intravenous contrast. (A) Mass in the left infrahilar region with a maximum diameter of approximately 55mm (arrow), with associated hypodense mediastinal adenopathy. (B) Pulmonary nodule measuring 20mm located at the edge of the posterolateral segment of the left inferior lobule (thick arrow), probably linked to the satellite metastatic mass of the primary tumour located in the infrahilar region (thin arrow).

In our view, this is a case of CSS caused by a metastatic tumour probably secondary to lung carcinoma; however, we lack anatomical pathology findings to support our hypothesis. The tumours most frequently causing skull-base metastasis are prostate and breast cancers; lung cancers are the fourth most common type (approximately 6% of all cases of skull-base metastasis).3 However, there is only one published case of CSS caused by metastasis of lung cancer (more specifically lung adenocarcinoma).4

Lastly, in patients showing involvement of several lower cranial nerves, differential diagnosis should aim to distinguish between carcinomatous meningitis (which is especially likely to affect these nerves in cases of basal arachnoiditis due to their caudal location) and a localised anomaly able to affect multiple nerves since they are very near to one another as they exit the base of the skull. The first diagnostic approach should aim to assess the anatomy of the impaired nerves to determine whether they are affected by a single topographic lesion. Once this step has been completed, we suggest delaying CSF tests until an accurate neuroimaging study of the area has been performed; MRI will be used in most cases of jugular foramen syndromes.3

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Larsen A, Feria-Vilar I, Collado R, Segura T. Síndrome de Collet-Sicard metastásico. Neurología. 2017;32:399–401.