Teleneurology was initially developed to provide care for complex, acute disorders in patients living in remote places, as was the case with telestroke.1 However, in recent years its use has been expanded to treat other neurological diseases, and teleneurology has been gradually incorporated into routine outpatient follow-up.2 Benefits include a reduction in time and travel costs for patients, improved access from remote areas, and perceived satisfaction among professionals and patients and their family members. Its limitations include the loss of traditional in-person relationships, the inability to perform a complete neurological examination, and neurologists’ concerns about a possible loss of diagnostic accuracy.3 We may distinguish 3 means of communication between neurologists and patients in teleneurology: telephone, audiovisual systems, and written consultation.4 We propose the abbreviations t-consultation for telephone consultations, v-consultation for video consultations, and e-consultation5 for written consultations.

Since the publication in Spain of Royal Decree 463/2020,6 declaring the state of alarm that transferred management of the healthcare crisis caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (COVID-19 disease) to the central government,7 reorganising habitual clinical care in different areas of knowledge8 has been essential in promoting the development of strategies to avoid contact between neurologists and patients.9 While no information is currently available on the virulence of this disease in patients with neuromuscular diseases, they should generally be considered a high-risk population.10

We report the experience with teleneurology at our neuromuscular diseases unit through an observational, prospective study conducted from 14 March 2020 (beginning of the state of alarm) to 24 April 2020. We included 88 consecutive patients in the sample, and collected demographic and clinical variables (age, sex, diagnosis, and screening for COVID-19 symptoms); and variables related to communication: person interviewed (patient or carer), type of electronic consultation (t-consultation, v-consultation, or e-consultation), distance from hospital to the place of the interview as measured with the Google Maps application, and estimated fuel savings. The cost of travel was estimated considering current price of unleaded 95 petrol (є1.30/L) and assumed the average fuel consumption of a sedan vehicle with 2 occupants, 8 L/100 km. These data were compared against data from the same period in 2019.

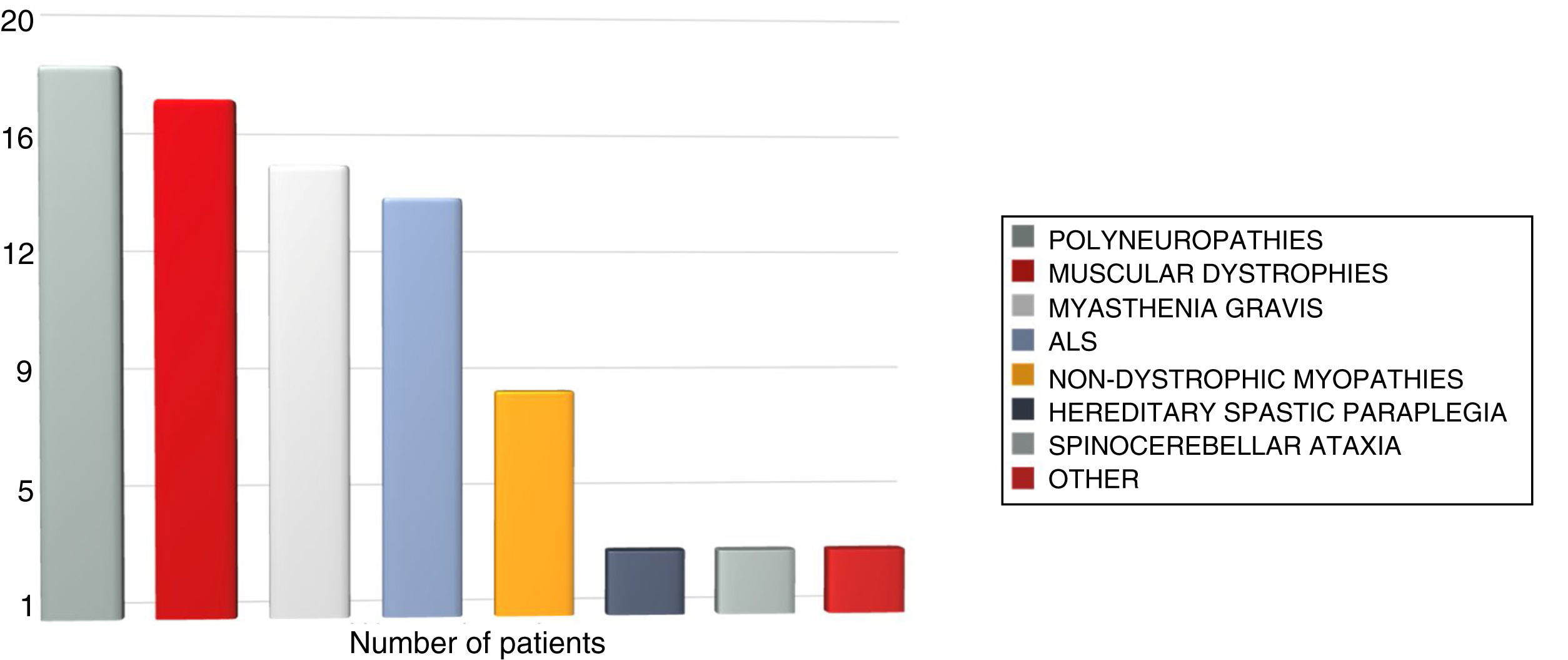

A total of 86 of the 88 patients or carers used electronic consultation (97.7%). All individuals initially agreed to use t-consultation and 8 patients (9.3%) were reassessed by v-consultation (4 patients with myasthenia gravis, 2 with muscular dystrophy, and 2 with other conditions) due to poor symptom control or unexpected symptom progression. Two patients reassessed by v-consultation (2.3% of the total) used e-consultation to report events during subsequent progression. None required emergency hospital care after electronic consultation. Mean age of the patients was 52.6 years; men accounted for 56.9% of the sample. In 13.9% of cases, patients needed the help of their carer to contact their neurologist. The total travel distance saved was 5591.7 km (63.68 km per patient). The estimated total fuel saving amounted to є684.4, with a mean expenditure per consultation of є7.6. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of neuromuscular diseases attended.

None of the patients presented symptoms compatible with COVID-19. The percentage of patients attended at the unit in the same period in 2019 was 88.7% (79 of the 89 scheduled consultations), 9% less than in 2020.

The emergency move from in-person consultations at our neuromuscular diseases unit to a teleneurology system during the COVID-19 pandemic improved access and decreased the ratio of non-attendance with regard to the previous year. The participation of carers was required for effective communication with some patients. This type of care avoided the need for travel for patients whose main symptom is muscle weakness, which impairs mobility, and led to fuel savings. Implementation of teleneurology at our unit has enabled continuity of care. The lockdown of patients included in this study appears to have been a safe and effective method of preventing new cases of COVID-19.

Once the COVID-19 pandemic is over, teleneurology strategies should be developed to coexist with in-person neurological care for patients with neuromuscular diseases under routine outpatient follow-up. We believe that abbreviations t-consultation, v-consultation, and e-consultation simplify discussion of the type of communication used with each patient.

Author contributionsAll authors have participated in patient assessment, statistical analysis, and drafting of the article.

Please cite this article as: Romero-Imbroda J, Reyes-Garrido V, Ciano-Petersen NL, Serrano-Castro PJ. Implantación emergente de un servicio de Teleneurología en la Unidad de Neuromuscular del Hospital Regional de Málaga durante la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2. Neurología. 2020;35:415–417.