Functional health, a reliable parameter of the impact of disease, should be used systematically to assess prognosis in paediatric intensive care units (PICU). Developing scales for the assessment of functional health is therefore essential. The Paediatric Overall and Cerebral Performance Category (POPC, PCPC) scales have traditionally been used in paediatric studies. The new Functional Status Scale (FSS) was designed to provide more objective results. This study aims to confirm the validity of the FSS compared to the classic POPC and PCPC scales, and to evaluate whether it may also be superior to the latter in assessing neurological function.

Patients and methodWe conducted a retrospective descriptive study of 266 children with neurological diseases admitted to intensive care between 2012 and 2014. Functional health at discharge and at one year after discharge was evaluated using the PCPC and POPC scales and the new FSS.

ResultsGlobal FSS scores were found to be well correlated with all POPC scores (P<.001), except in category 5 (coma/vegetative state). Global FSS score dispersion increases with POPC category. The neurological versions of both scales show a similar correlation.

DiscussionComparison with classic POPC and PCPC categories suggests that the new FSS scale is a useful method for evaluating functional health in our setting. The dispersion of FSS values underlines the poor accuracy of POPC-PCPC compared to the new FSS scale, which is more disaggregated and objective.

La salud funcional, parámetro adecuado de morbilidad, debería constituir un estándar pronóstico de las unidades de cuidados intensivos pediátricos (UCIP), siendo fundamental el desarrollo de escalas para su valoración. Las categorías de estado global y cerebral pediátrico (CEGP-CECP) se han empleado clásicamente en estudios pediátricos; el desarrollo de la nueva Escala de estado funcional (FSS) busca mejorar la objetividad. El objetivo del trabajo es comprobar si la escala FSS es un instrumento válido frente a la clásica CEGP-CECP, y si, incluso, posee mejores cualidades evaluadoras de la funcionalidad neurológica.

Pacientes y métodoEstudio retrospectivo descriptivo de los 266 niños con enfermedad neurológica ingresados en la UCIP durante 3 años (2012-2014). Se valora su salud funcional al alta y tras un año del ingreso en UCIP, según las categorías CEGP-CECP y la nueva FSS, comparando ambas escalas mediante análisis de correlación (Rho de Spearman).

ResultadosLa comparación de varianzas de FSSglobal en cada intervalo de CEGP muestra buena correlación para todas las comparaciones (p<0,001), excepto en la categoría «5=coma-vegetativo». La dispersión de FSSglobal aumenta a medida que lo hace la categoría CEGP. La correlación es similar en la versión neurológica de ambas escalas.

DiscusiónLa nueva escala FSS parece ser un método útil para evaluar salud funcional en nuestro medio, tras su comparación con las clásicas categorías CEGP-CECP. La dispersión de los valores de la escala FSS indica falta de precisión del sistema CEGP-CECP, comparado con la nueva escala FSS, más desglosada y objetiva.

Patients with primary and secondary neurological diseases represent a considerable proportion of all patients admitted to paediatric intensive care units (PICU). Brain injury is a frequent cause of morbidity and mortality in these units, and a major determinant of functional prognosis.1,2

Advances in paediatric intensive care have led to improvements in survival rates3; therefore, raw mortality rates are no longer sufficient to define the outcomes of paediatric intensive care. The main objective of these units has evolved from simply “saving lives” to “saving functional lives,” ensuring the best possible functional outcomes.4 Over the past few decades, studies into the prognosis of children requiring intensive care have changed their focus from mortality to functional outcomes and quality of life.5,6

Several different parameters are used to assess morbidity in paediatric patients receiving intensive care, including quality of life, health-related quality of life, and functional health. These parameters should be measured at discharge and followed up in the long term as part of the standard assessment protocols in PICUs. The concepts of quality of life and health-related quality of life present the limitation that they represent an individual's perception of their own health and disease, which cannot be easily evaluated in a large proportion of children. Therefore, the concept of “functional health” is more appropriate for evaluating outcomes in children receiving intensive care. Paediatric functional status assessment should address the changes inherent to growth and development, and will inevitably involve a subjective component. Numerous paediatric functional assessment scales have been developed in order to minimise subjectivity. The Paediatric Overall Performance Category (POPC) and Paediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) scales are global scales based on observer impressions. They are valid and reliable, despite several limitations, and have been used in multiple studies of paediatric populations.7–9 In 2009, Pollack et al.10 published a new functional outcome assessment scale, the Functional Status Scale (FSS), which enables more disaggregated, defined, and accurate assessment of all types of patients, providing more objective results.11 The scale evaluates 6 functional domains (mental status, sensory functioning, communication, motor functioning, feeding, and respiratory status), which can be classified into 6 functional levels: (1) normal, (2) mild dysfunction, (3) moderate dysfunction, (4) severe dysfunction, (5) very severe dysfunction, and (6) death (the last category was added to the original scale to match the POPC and PCPC scales).

Our purpose was to evaluate the validity of the new FSS as compared against the classic POPC and PCPC scales, and to determine whether it is superior in evaluating neurological function.

Material and methodsWe conducted a descriptive, retrospective, observational analysis of the 266 children admitted to the PICU of a tertiary hospital between January 2012 and December 2014 due to primary or secondary neurological disease. We evaluated patient outcomes in terms of mortality and morbidity. Morbidity was evaluated by assessing functional status using the POPC and PCPC scales (Table 1) and the FSS one year after discharge from the PICU. The 6 items of the new FSS enable a more disaggregated (and therefore more objective) evaluation; however, as this complicates assessment and data analysis, the items were recoded as in the study by Pollack et al.12 We calculated the mean score for the 6 items, establishing a new subscore, “overall FSS,” and the mean score of the items evaluating neurological function, “neurological FSS,” which is further subdivided into “neuro1 FSS,” including scores from items 1-4, and “neuro2 FSS,” for scores from items 1-3, which evaluate cognitive function. Based on these scores, a patient's functional status may be classified as favourable (normal function or mild dysfunction) or unfavourable (moderate, severe, or very severe dysfunction, or death), as in the study by Bone et al.13 Functional assessment was performed at baseline, at discharge from the PICU, and one year after discharge, since improvements and recovery may not be significant until some time has passed. We compared scores at discharge and one year after discharge against baseline scores; a change from a favourable to an unfavourable functional status category was regarded as clinically significant worsening of functional status.

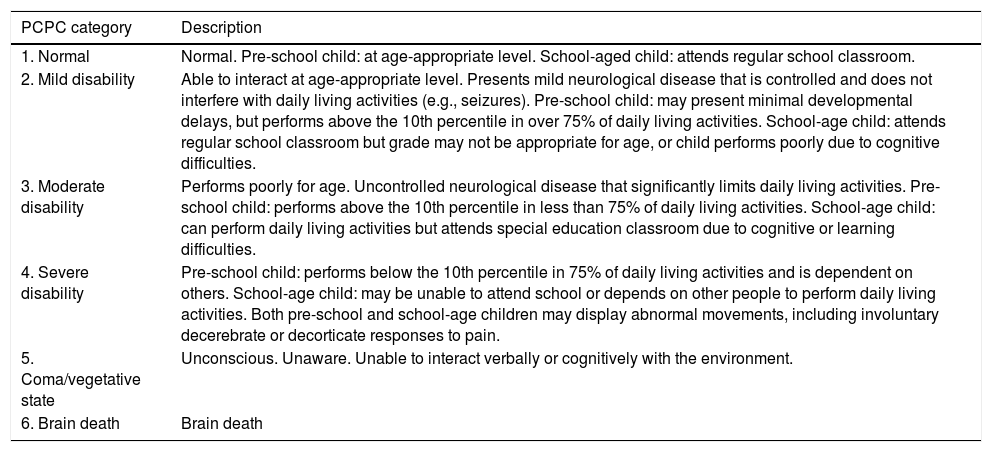

POPC and PCPC categories of global and neurological functional status.7

| PCPC category | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Normal | Normal. Pre-school child: at age-appropriate level. School-aged child: attends regular school classroom. |

| 2. Mild disability | Able to interact at age-appropriate level. Presents mild neurological disease that is controlled and does not interfere with daily living activities (e.g., seizures). Pre-school child: may present minimal developmental delays, but performs above the 10th percentile in over 75% of daily living activities. School-age child: attends regular school classroom but grade may not be appropriate for age, or child performs poorly due to cognitive difficulties. |

| 3. Moderate disability | Performs poorly for age. Uncontrolled neurological disease that significantly limits daily living activities. Pre-school child: performs above the 10th percentile in less than 75% of daily living activities. School-age child: can perform daily living activities but attends special education classroom due to cognitive or learning difficulties. |

| 4. Severe disability | Pre-school child: performs below the 10th percentile in 75% of daily living activities and is dependent on others. School-age child: may be unable to attend school or depends on other people to perform daily living activities. Both pre-school and school-age children may display abnormal movements, including involuntary decerebrate or decorticate responses to pain. |

| 5. Coma/vegetative state | Unconscious. Unaware. Unable to interact verbally or cognitively with the environment. |

| 6. Brain death | Brain death |

| POPC category | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Normal | Performs at age-appropriate level in daily living activities. Medical or physical problems do not interfere with normal activity. |

| 2. Mild disability | Mild medical or physical problems causing minor limitations that do not interfere with normal life (e.g., asthma). Pre-school child: may present disabilities compatible with future independent life (e.g., single amputation) and is able to perform over 75% of age-appropriate daily living activities. |

| 3. Moderate disability | Medical or physical problems interfere with normal activity. Pre-school child: unable to perform some daily living activities. School-age child: able to perform multiple daily living activities but presents physical disability (e.g., cannot participate in sports competitions). |

| 4. Severe disability | Pre-school child: unable to perform most daily living activities. Pre-school child: dependent for most daily living activities. |

| 5. Coma/vegetative state | Unconscious. Unaware. Unable to interact verbally or cognitively with the environment. |

| 6. Brain death | Brain death |

PCPC: Paediatric Cerebral Performance Category; POPC: Paediatric Overall Performance Category.

We compared global POPC score against overall FSS score, and PCPC score against both neurological FSS scores (neuro1 and neuro2 FSS), and assessed the dispersion of FSS scores for each POPC/PCPC category.

Quantitative data were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and are presented as measures of central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion (standard deviation [SD] or interquartile range [IQR], respectively). Qualitative variables are expressed as frequencies or percentages. Correlation between scales was analysed using the Spearman ρ for baseline scores from both scales. We compared the dispersion of overall FSS scores for each POPC category, and of neuro1 and neuro2 FSS scores for each PCPC category (normal, mild disability, moderate disability, severe disability, coma/vegetative state). Dispersion was assessed using standard deviations and percentile ranges (25th-75th, 10th-90th, 5th-95th) of overall FSS and neurological FSS scores for each POPC and PCPC category, respectively.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the region of Aragon. Data were anonymised. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistics software (version 18.0). The threshold for statistical significance was set at α=.05.

ResultsBetween 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2014, our hospital's PICU recorded 1178 admissions; 323 (27.5%) correspond to 266 children presenting neurological diseases either as the reason for admission or with onset during hospitalisation at the PICU. The statistical analysis considers the total number of patients. For patients admitted to the PICU on multiple occasions, we analysed the first episode only. The median age of our sample was 58 months (approximately 4.8 years) (IQR, 94). Of the 266 patients included in the study, 163 (61.3%) were boys and 103 (38.7%) were girls. Median duration of hospitalisation at the PICU was 2 days (IQR, 2).

During this period, the overall mortality rate at the PICU was 2.1% (25 deaths from a total of 1178 admissions), whereas mortality in the sample of neurological patients was 2.5% of all admissions (8 deaths from a total of 323 admissions) and 3% of all the patients included.

At discharge, POPC scores showed either no changes or clinically significant improvements in overall function in 73.7% of the sample, and worsening in 26.3%. PCPC scores revealed either no changes or clinically significant improvements in neurological function in 89.5% of patients. The new FSS yielded more optimistic results: at discharge, overall (overall FSS), neurological (neuro1 FSS), and cognitive function (neuro2 FSS) remained unchanged or significantly improved in 96.2% of patients. One year after discharge from the PICU, overall (POPC) and neurological function (PCPC) remained unchanged or significantly improved in 94.3% and 95.1% of the sample, respectively. According to the FSS, overall, neurological, and cognitive function remained unchanged or improved in 89.5%, 89.1%, and 89.5% of patients, respectively.

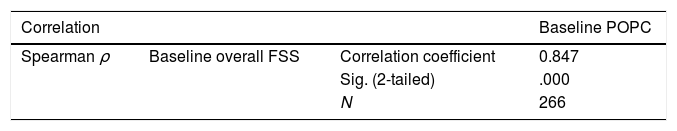

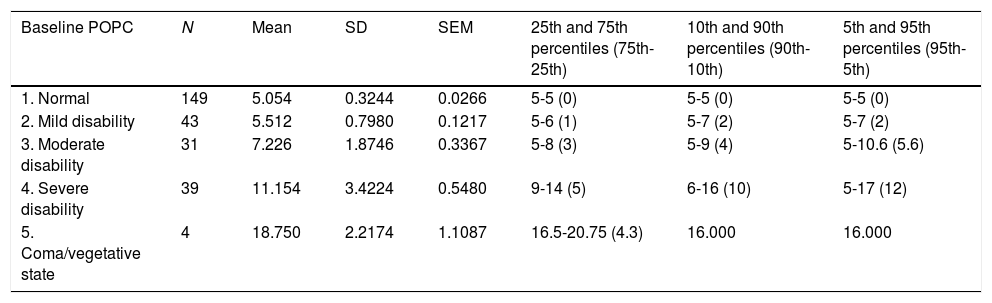

Table 2 shows the correlation between the POPC and PCPC scales and the FSS (Spearman ρ). We analysed the correlations between scores for overall function (overall FSS vs POPC) and for neurological function (neuro1 and neuro2 FSS vs PCPC). Table 3 analyses the dispersion of overall FSS scores for each POPC category. Similar findings were obtained for neurological function (neuro1 and neuro2 FSS vs PCPC).

Correlation between overall FSS scores and POPC categories, and between neuro1 and neuro2 FSS scores and PCPC categories.

| Correlation | Baseline POPC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman ρ | Baseline overall FSS | Correlation coefficient | 0.847 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | ||

| N | 266 | ||

| Correlation | Baseline PCPC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman ρ | Baseline neuro1 FSS | Correlation coefficient | 0.813 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | ||

| N | 266 | ||

| Baseline neuro2 FSS | Correlation coefficient | 0.804 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | ||

| N | 266 | ||

Correlations are significant at the .01 level (2-tailed).

FSS: Functional Status Scale; PCPC: Paediatric Cerebral Performance Category; POPC: Paediatric Overall Performance Category; Sig.: statistical significance.

Analysis of dispersion between overall FSS and POPC.

| Baseline POPC | N | Mean | SD | SEM | 25th and 75th percentiles (75th-25th) | 10th and 90th percentiles (90th-10th) | 5th and 95th percentiles (95th-5th) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Normal | 149 | 5.054 | 0.3244 | 0.0266 | 5-5 (0) | 5-5 (0) | 5-5 (0) |

| 2. Mild disability | 43 | 5.512 | 0.7980 | 0.1217 | 5-6 (1) | 5-7 (2) | 5-7 (2) |

| 3. Moderate disability | 31 | 7.226 | 1.8746 | 0.3367 | 5-8 (3) | 5-9 (4) | 5-10.6 (5.6) |

| 4. Severe disability | 39 | 11.154 | 3.4224 | 0.5480 | 9-14 (5) | 6-16 (10) | 5-17 (12) |

| 5. Coma/vegetative state | 4 | 18.750 | 2.2174 | 1.1087 | 16.5-20.75 (4.3) | 16.000 | 16.000 |

FSS scores for POPC categories “normal” and “mild disability” are similar, with increases of 1.5-2 points for “moderate disability,” 4 points for “severe disability,” and 7 points for “coma/vegetative state.”

FSS: Functional Status Scale; POPC: Paediatric Overall Performance Category; SD: standard deviation; SEM: standard error of the mean.

Neurological disease represents an essential part of the responsibilities of PICUs. Survivors attended at these units are at high risk of presenting physical, cognitive, or psychological sequelae, which may persist for months or years after the episode. Brain injury is one of the main causes of death at PICUs,2 and is largely responsible for the high morbidity rates observed in these patients. Whether it is primary or secondary to a non-neurological condition, brain injury plays a decisive role in morbidity and mortality in paediatric patients requiring intensive care. Our results provide a global view of neurocritical care in our hospital's PICU between January 2012 and December 2014. During this period, around one-third of all admissions (27.5%) presented neurological diseases (acute or chronic, primary or secondary), which reflects the importance of paediatric neurocritical care.1,14 These episodes correspond to 266 paediatric patients requiring admission to the PICU on one or more occasions. The mortality rate during the 3-year period analysed was 3% in our patient sample (2.5% of all admissions); however, PICUs no longer aim merely to save lives, but seek to preserve as much functional capacity as possible. Neurological diseases have a great impact on daily life; therefore, standardised neurological assessment and adequate support and rehabilitation play an essential role in improving functional health. It is of the utmost importance for paediatric neurologists and intensivists to implement neuroprotective strategies for all paediatric critical care patients; the development of multidisciplinary paediatric neurointensive care teams can help optimise research and care provision both at the PICU and in the medium term after discharge.4

Numerous scales have been developed for assessing functional outcomes in these patients. Paediatrics as a discipline faces the challenge of developing a functional outcome measure that is well-defined, quantitative, reliable, and quick to administer; such a tool should be objective and applicable to as wide an age range as possible, and to hospitalised patients in any setting. The instruments currently available have a number of limitations, including their subjectivity, the limited age range for which they have been validated, and the time taken to administer them. The classic POPC and PCPC scales modified for paediatric patients are based on the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS), which was initially developed to evaluate stroke outcomes in adults. The paediatric version of the GOS, which was designed to assess the outcomes of traumatic brain injury,15 has been used in several studies but is no longer in use due to its lower precision.16 Fiser8 validated the scale in paediatric patients using the categories of the POPC and PCPC, 2 general scales based on observer impressions. This led to the standardisation and validation in 1992 of the assessment of neurological and non-neurological function (i.e., cognitive and physical function) in survivors discharged from PICUs. Although these categories provide only an overview of overall and cognitive function, they are validated and show an association with measures from the Bayley Psychomotor Developmental Index, the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test,9 and the Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales; therefore, they constitute a valid, reliable tool for evaluating the outcomes of paediatric patients receiving intensive care.7 Despite the limitations of the POPC and PCPC scales and the possibility of a learning effect, multiple studies including paediatric samples have used them to evaluate outcomes after PICU admissions, with many reporting satisfactory results.17,18

In 2009, Pollack et al.10 published a new functional outcome assessment scale, the FSS, which enables a more disaggregated, defined, accurate assessment of all types of patients, aiming to improve upon the objectivity of the POPC and PCPC scales.11

Our study classified functional outcomes after discharge from the PICU into 2 categories: improvement or lack of change with respect to baseline function, or worsening of functional status. Outcomes were evaluated at discharge and at one year. For the analysis of the results, a change from a favourable to an unfavourable functional status was regarded as clinically significant worsening. We evaluated overall and neurological functional status using the POPC and PCPC scales and the FSS (overall, neuro1, and neuro2 FSS). Although over 70% of the sample, according to the POPC, and over 85%, according to the PCPC, presented favourable functional outcomes after discharge from the PICU, paediatric intensive care should focus particularly on the small yet considerable percentage of patients presenting a clinically significant worsening of functional status, given the great impact this may have on their quality of life. The new FSS subscores (overall, neuro1, and neuro2 FSS) provide more optimistic results, revealing clinically significant favourable outcomes in over 95% of patients. However, the most important consideration in these patients is prognosis in the medium and long term. At one year after discharge, the majority of patients presented a functional improvement compared to baseline according to the POPC and PCPC scales. Over 90% of patients showed clinically significant improvements in functional outcomes, which reflects the brain's ability to repair itself (neuroplasticity) and the importance of rehabilitation in these patients.19 Although the FSS yields more optimistic results than the POPC and PCPC scales for functional status at discharge from the PICU, the percentage of patients with a favourable functional progression was slightly lower at one year, mainly due to underlying neurodegenerative diseases in some patients.

At baseline, the POPC and PCPC scales and the FSS showed similar results. Our analysis found a very strong, positive, statistically significant correlation between POPC and overall FSS scores (ρ=0.847; P<.001), and between PCPC and neuro1 (ρ=0.813) and neuro2 FSS scores (ρ=0.804) (P<.001). FSS scores increased in parallel with severity of POPC categories, with the magnitude of change increasing in line with the severity of functional impairment. In line with the 2014 study by Pollack et al.12 (a multicentre study including over 5000 patients), we evaluated the dispersion of overall FSS scores for each POPC category and the dispersion of neuro1 and neuro2 FSS scores for each PCPC category; our analysis revealed a lack of precision of the POPC and PCPC scales compared to the new FSS, which is more disaggregated and objective. Analysis of the dispersion of overall FSS scores shows a strong association with all POPC categories (P<.001) except for category 5 (coma/vegetative state), due to the small number of patients classified into this category. The dispersion of overall FSS is greater for more severe POPC categories; this is probably explained by the progressive decrease in the number of patients with more severe dysfunction according to the POPC scale, given that dispersion tends to decrease with larger samples. Regarding neurological function, a similar relationship was observed between PCPC categories and neuro1 and neuro2 FSS scores.

In our setting, the ability of PICUs to evaluate changes in patients’ functional status is directly correlated with the accuracy of the tools used. In our study, as in the study by Pollack et al.,12 FSS scores increased significantly with more severe POPC/PCPC categories; in fact, these increases were more marked as severity progressed, which suggests that the FSS is a useful tool for detecting changes in functional status in descriptive or interventional studies in our setting. Furthermore, the FSS provides more objective results due to its disaggregated, more specific design, which makes it a more reliable tool for evaluating functional outcomes in paediatric patients with neurological disease. In the light of both of these observations, the FSS should be used to evaluate functional outcomes in paediatric patients receiving intensive care.

The minimal differences observed between baseline and one-year scores may also demonstrate the usefulness of the scale to predict medium- and long-term functional outcomes, as shown by Fiser et al.8 in their study of the POPC and PCPC scales.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Madurga-Revilla P, López-Pisón J, Samper-Villagrasa P, Garcés-Gómez R, García-Íñiguez JP, Domínguez-Cajal M, et al. Valoración funcional tras tratamiento neurointensivo pediátrico. Nueva escala de estado funcional (FSS). Neurología. 2020;35:311–317.