We present the Spanish Society of Neurorehabilitation’s guidelines for adult acquired brain injury (ABI) rehabilitation. These recommendations are based on a review of international clinical practice guidelines published between 2013 and 2020.

DevelopmentWe establish recommendations based on the levels of evidence of the studies reviewed and expert consensus on population characteristics and the specific aspects of the intervention or procedure under research.

ConclusionsAll patients with ABI should receive neurorehabilitation therapy once they present a minimal level of clinical stability. Neurorehabilitation should offer as much treatment as possible in terms of frequency, duration, and intensity (at least 45–60minutes of each specific form of therapy that is needed). Neurorehabilitation requires a coordinated, multidisciplinary team with the knowledge, experience, and skills needed to work in collaboration both with patients and with their families. Inpatient rehabilitation interventions are recommended for patients with more severe deficits and those in the acute phase, with outpatient treatment to be offered as soon as the patient’s clinical situation allows it, as long as intensity criteria can be maintained. The duration of treatment should be based on treatment response and the possibilities for further improvement, according to the best available evidence. At discharge, patients should be offered health promotion, physical activity, support, and follow-up services to ensure that the benefits achieved are maintained, to detect possible complications, and to assess possible changes in functional status that may lead the patient to need other treatment programmes.

Guía para la práctica clínica en neurorrehabilitación de personas adultas con daño cerebral adquirido (DCA) de la Sociedad Española de Neurorrehabilitación. Documento basado en la revisión de guías de práctica clínica internacionales publicadas entre 2013−2020.

DesarrolloSe establecen recomendaciones según el nivel de evidencia que ofrecen los estudios revisados referentes a aspectos consensuados entre expertos dirigidos a definir la población, características específicas de la intervención o la exposición bajo investigación.

ConclusionesDeben recibir neurorrehabilitación todos aquellos pacientes que, tras un DCA, hayan alcanzado una mínima estabilidad clínica. La neurorrehabilitación debe ofrecer tanto tratamiento como sea posible en términos de frecuencia, duración e intensidad (al menos 45–60 minutos de cada modalidad de terapia específica que el paciente precise). La neurorrehabilitación requiere un equipo transdisciplinar coordinado, con el conocimiento, la experiencia y las habilidades para trabajar en equipo tanto con pacientes como con sus familias. En la fase aguda y para los casos más graves, se recomiendan programas de rehabilitación en unidades hospitalarias procediéndose a tratamiento ambulatorio tan pronto como la situación clínica lo permita, y se puedan mantener los criterios de intensidad. La duración del tratamiento debe basarse en la respuesta terapéutica y en las posibilidades de mejoría en base al mayor grado de evidencia disponible. Al alta deben ofrecerse servicios de promoción de la salud, actividad física, apoyo y seguimiento para garantizar que se mantengan los beneficios alcanzados, detectar posibles complicaciones o valorar posibles cambios en la funcionalidad que hagan necesario el acceso a nuevos programas de tratamiento.

Currently, no consensus criteria have been published in Spain on the management of rehabilitation interventions and care in the context of acquired brain injury (ABI), which can lead to inequities in care quality and access. This situation is further complicated by the fact that, despite the commendable efforts made in their development, the limited number of guidelines and recommendations issued by various local, regional, and national institutions, seeking to unify these patients’ treatment needs, lack recent updates and therefore do not account for the latest advances in this area of considerable scientific productivity.

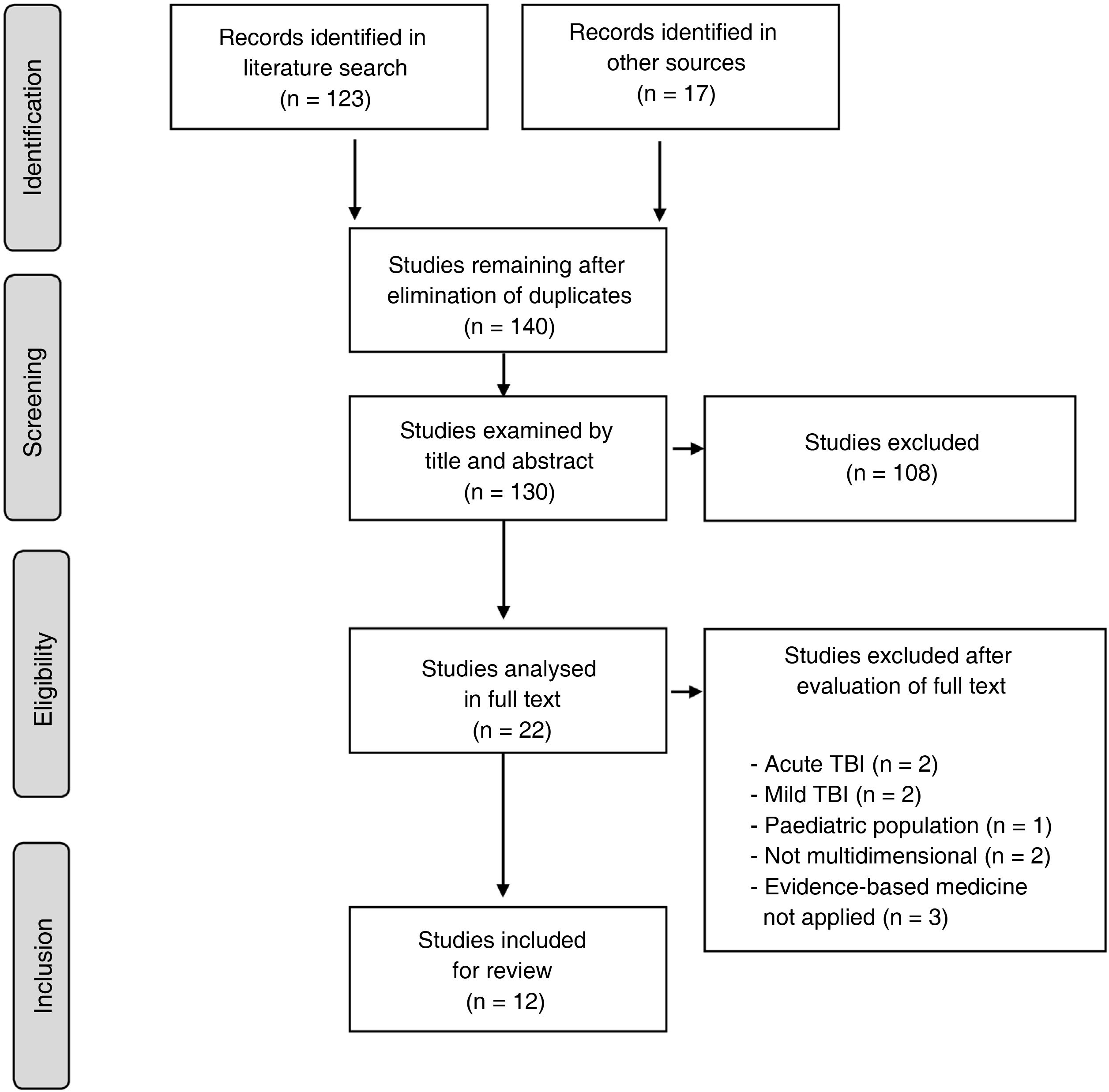

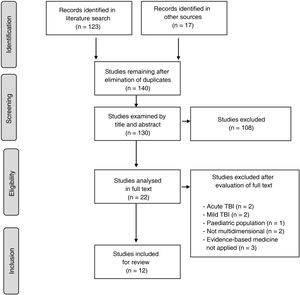

In the light of this, the present document is intended to guide clinical practice in neurorehabilitation, in accordance with the best and most recent level of evidence currently available on rehabilitation management in adult patients (> 16 years) after stroke (either ischaemic or haemorrhagic) or moderate-severe traumatic brain injury (TBI). These guidelines, developed on behalf of the Spanish Society of Neurorehabilitation (SENR), aim to improve the quality of care provided to these patients. To that end, the authors reviewed and extracted data and levels of evidence on 5 key aspects of neurorehabilitation, established by consensus, from clinical practice guidelines (CPG) and consensus statements published by different national and international organisations between 2013 and 2020 (Fig. 1).

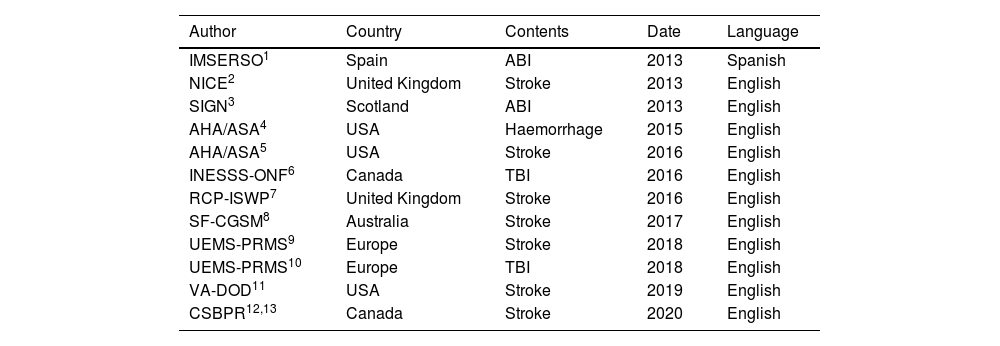

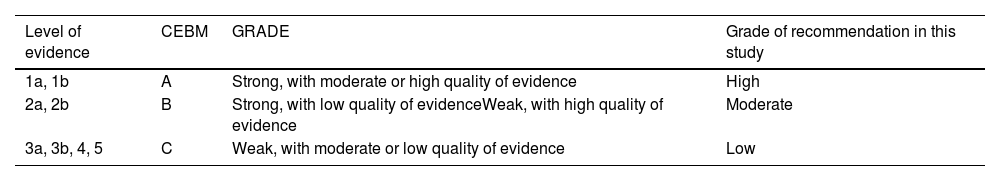

A total of 12 CPGs were finally included in the systematic review.1–13Table 1 summarises the 12 guidelines meeting the inclusion criteria for the review and highlights the most relevant aspects of each. Table 2 shows the grades of recommendation and levels of evidence for each recommendation.

Guidelines included in the study.

| Author | Country | Contents | Date | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMSERSO1 | Spain | ABI | 2013 | Spanish |

| NICE2 | United Kingdom | Stroke | 2013 | English |

| SIGN3 | Scotland | ABI | 2013 | English |

| AHA/ASA4 | USA | Haemorrhage | 2015 | English |

| AHA/ASA5 | USA | Stroke | 2016 | English |

| INESSS-ONF6 | Canada | TBI | 2016 | English |

| RCP-ISWP7 | United Kingdom | Stroke | 2016 | English |

| SF-CGSM8 | Australia | Stroke | 2017 | English |

| UEMS-PRMS9 | Europe | Stroke | 2018 | English |

| UEMS-PRMS10 | Europe | TBI | 2018 | English |

| VA-DOD11 | USA | Stroke | 2019 | English |

| CSBPR12,13 | Canada | Stroke | 2020 | English |

“Author” refers to the society or authority responsible for publishing the guidelines; “country” refers to country or region of origin; “contents” refers to the disease addressed by the recommendations; and “year” refers to the year in which the latest update to the document was published.

ABI: acquired brain injury; AHA/ASA: American Heart Association-American Stroke Association; CSBPR: Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Stroke Rehabilitation Practice Guidelines; IMSERSO: Instituto de Migraciones y Servicios Sociales – Fundación Reintegra; INESSS-ONF: Institut National d’Excellence en Santé et en Services Sociaux – Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; RCP-ISWP: Royal College of Physicians: Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party; SF-CGSM: Stroke Foundation – Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management; SIGN: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; TBI: traumatic brain injury; UEMS-PRMS: European Union of Medical Specialists – Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine Section; VA-DOD: Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of Stroke Rehabilitation. Department of Veterans Affairs – Department of Defense.

Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation.

| Level of evidence | CEBM | GRADE | Grade of recommendation in this study |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a, 1b | A | Strong, with moderate or high quality of evidence | High |

| 2a, 2b | B | Strong, with low quality of evidenceWeak, with high quality of evidence | Moderate |

| 3a, 3b, 4, 5 | C | Weak, with moderate or low quality of evidence | Low |

The different health systems in Spain vary greatly in terms of the evaluation of patients’ rehabilitation needs after ABI. This variability results in deep inequalities in the provision of neurorehabilitation care, which has clinical and ethical repercussions.14 If we accept that rehabilitation plays an important role in facilitating recovery and participation in the community, then we must also acknowledge the significant healthcare, social, and obviously financial impact of the decision of whether or not to offer this treatment. To date, no scientific evidence has been published to justify, at least from a clinical perspective, a series of universally accepted criteria for access to centres or programmes offering specialised neurorehabilitation. Therefore, this decision is often made subjectively, influenced by personal and organisational factors, as well as by the personal characteristics of the clinician or institution responsible for triage.15,16 In fact, the current literature includes numerous criteria for referral to rehabilitation centres, fundamentally based on personal, structural, and economic considerations.15,17 According to a recent meta-analysis,18 the factors most frequently limiting access to rehabilitation are presence of a premorbid functional or cognitive disability, age > 70 years, and lack of family support. A recent study by the same working group15 found that the conditions most frequently considered by the physicians responsible for referring patients to neurorehabilitation systems to treat disability after brain injury were premorbid cognitive, communication, and mobility status, whereas the most frequently cited exclusion criteria were mobility after stroke, social support, and cognitive status after stroke.

Overall, triage processes are currently exposed to individual susceptibility of the person or organisation responsible to be influenced by financial, personal, structural, or attitudinal factors. Despite the available objective selection criteria, the purpose of patient selection can vary greatly, for instance due to funding allocation, the availability and proximity to the patient’s home of healthcare resources, or other personal/institutional priorities related to a wide range of considerations, including efficiency, effectiveness, expected benefit, or cost-benefit and cost-efficacy calculations.19 As a result of all of these influences, the variables established to date for the selection of candidates for neurorehabilitation probably result in the inclusion of ineligible patients and vice versa. In this context, several authors have proposed that the best criterion for determining capacity to benefit from rehabilitation (rather than the likelihood of favourable outcomes) is probably the existence of a demonstrated benefit after inclusion in the relevant programme, while ensuring that patients who are not admitted receive the necessary support and resources.20Table 3 includes the recommendations related to admission to rehabilitation services and the corresponding grades of recommendation in the main guidelines reviewed.

- -

SENR recommendations:

- 1.

All patients should receive neurorehabilitation treatment following a stroke or TBI, once minimal clinical stability is achieved and potentially life-threatening complications are controlled.

- 2.

Rehabilitation is indicated in patients presenting a loss of physical, cognitive, sensory, emotional, behavioural, and/or functional capacity (structures and functions), with an impact on the activities and/or participation of the patients with ABI.

- 3.

The patient’s capacity for recovery must be established by professionals with accredited experience in the rehabilitation of patients with ABI, using validated, standardised tools adapted for the level of clinical severity.

- 1.

Who should receive neurorehabilitation treatment? Summary of recommendations.

| Recommendations | Grade of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Stroke | |

| Acute phase. All patients hospitalised following stroke should undergo initial assessment by rehabilitation experts as soon as possible after admission. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase. Patients with moderate-severe stroke and ready to start rehabilitation, whose rehabilitation objectives are likely to be achieved, should have the opportunity to participate in an inpatient rehabilitation programme. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase. All patients with stroke should start rehabilitation as early as deemed appropriate, providing that they are ready for this and are sufficiently stable from a medical perspective to participate actively in rehabilitation programmes. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase. Given the potential severity and complexity of disability resulting from intracranial haemorrhage, and the growing evidence on the efficacy of rehabilitation, all patients with intracranial haemorrhage should have access to multidisciplinary rehabilitation. | HighA (AHA-ASA) |

| Acute/subacute/chronic phases. Education of patients with stroke, as well as their families and caregivers, should be included in comprehensive treatment plans, and should be taken into account at all meetings between professionals and the treatment team, especially at times of care transition. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (aphasia). All patients with communication difficulties following stroke should receive speech therapy adapted to their individual requirements. | High(UEMS-PRMS) |

| Chronic phase. All community-dwelling patients who present difficulties with basic activities of daily living following stroke should be assessed by an experienced clinician. If problems with personal or extended daily living activities are confirmed, they should be offered specific treatment by an experienced clinical team. | HighStrong, with moderate level of evidence (SF-CGSM) |

| Chronic phase. All patients with stroke should receive training in the basic activities of daily living, adapted to their needs and to their final destination. | HighA (AHA-ASA) |

| Chronic phase. All patients referred to a long-term care facility following stroke should initially be assessed by medical, nursing, and rehabilitation professionals, as soon as possible after admission. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase. Patients and their families and caregivers should actively participate in the rehabilitation programme from an early stage. | ModerateC (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (aphasia). Patients with aphasia should be afforded rapid access to intensive rehabilitation programmes adapted to their needs, objectives, and the severity of their problems. | ModerateC (CSBPR) |

| Subacute/chronic phases. Patients with stroke and their families and caregivers should be prepared in advance to guarantee success in the different treatment stages and settings they will pass through over the course of rehabilitation. To that end, they should be provided with information and training materials, offered psychosocial support, and informed and assisted as needed in order to access community services and resources. | ModerateC (CSBPR) |

| Acute/subacute/chronic phases. All patients with stroke and their families and caregivers should be assessed to establish their capacity to cope with their new circumstances, the risk of depression, and other potential physical or psychological problems. | ModerateC (CSBPR) |

| Chronic phase. All patients with stroke should receive training in instrumental activities of daily living, adapted to their needs and to their final destination. | ModerateB (AHA-ASA) |

| Chronic phase. Patients with stroke and their families and caregivers should be given information, education, training, support, and access to the services needed when the patient returns to the community, in order to achieve the greatest possible level of social activity and participation. | ModerateC (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (aphasia). The existence of communication difficulties should be evaluated with validated screening tools in all patients with stroke. Screening tests should be conducted by a speech therapist or, should this not be possible, by other experienced professionals. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (aphasia). All patients with suspected communication difficulties should be referred to a speech therapist for formal evaluation, including the application of validated, reproducible tools addressing comprehension, verbal expression, reading, writing, voice, and level of communication. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Subacute phase. In the post-acute phase, rehabilitation needs should be established according to proper assessment of residual neurological deficits, activity limitations, cognitive status, psychosocial characteristics, ability to communicate, swallowing, previous functional status, other medical comorbidities, level of family or external support, ability for the patient’s care needs to be met in their setting, likelihood of returning home, and ability to participate in rehabilitation. | LowC (ASA-AHA) |

| Subacute phase (evaluation). The potential rehabilitation needs of all patients not initially meeting criteria for rehabilitation should be re-evaluated on a weekly basis for the first month, with subsequent periodic re-evaluation in accordance with their health status. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| TBI | |

| Chronic phase. Tailored treatment protocols should be developed to improve functional status in all patients with TBI, with a view to helping them to effectively meet the demands and challenges of everyday life. According to the needs and the disability profile of each patient, the therapeutic intervention may focus on social skills, basic/instrumental activities of daily living, workplace reintegration, problem-solving skills, decision-making, risk management, behaviour management, etc. | ModerateB (INESSS-ONF) |

| Acute phase. All patients with moderate-severe TBI should be afforded access to appropriate multidisciplinary rehabilitation services. | LowFundamental C (INESSS-ONF) |

| Acute phase. Rehabilitation programmes should have clear admission criteria including the following: diagnosis of TBI, medical stability, capacity to improve over the course of the rehabilitation process, capacity to learn and adhere to treatment, and sufficient tolerance to treatment. | LowFundamental F (INESSS-ONF) |

| Chronic phase. Patients with persistent disability following TBI should be given suitable access to specialised outpatient or community rehabilitation programmes, with a view to achieving progressive improvements that may enable successful reintegration into the community. | LowFundamental C (INESSS-ONF) |

| Chronic phase. All patients with persistent cognitive deficits following TBI should be offered cognitive rehabilitation with functional objectives. | LowC (INESSS-ONF) |

| Acute phase (aphasia). All patients presenting communication disorders following TBI should be offered an appropriate treatment programme. | LowC (INESSS-ONF) |

AHA/ASA: American Heart Association-American Stroke Association; CSBPR: Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Stroke Rehabilitation Practice Guidelines; INESSS-ONF: Institut National d’Excellence en Santé et en Services Sociaux – Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; SF-CGSM: Stroke Foundation – Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management; TBI: traumatic brain injury; UEMS-PRMS: European Union of Medical Specialists – Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine Section.

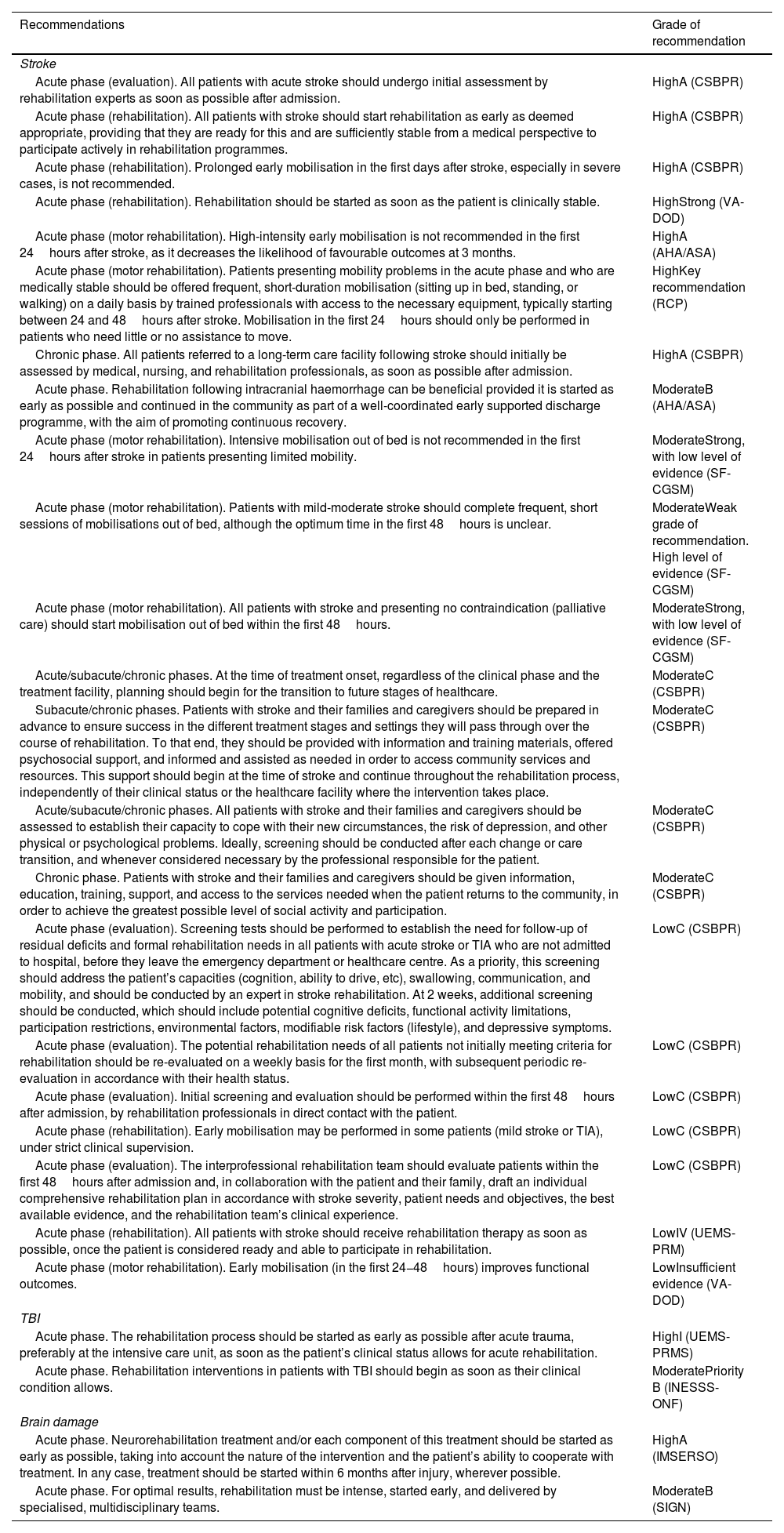

Most of the studies published to date conclusively assert that the effectiveness of neurorehabilitation increases with earlier treatment onset.21,22 It is generally accepted that neurorehabilitation should be started as early as possible, and must be adapted to the clinical situation of each individual patient.21,23–25 Generally, early treatment onset (3–30 days after stroke) tends to be associated with better outcomes. In fact, many studies have shown that, in both stroke and TBI, the number of days from injury to onset of rehabilitation is predictive of institutionalisation and functional status at discharge.26 Furthermore, earlier onset of neurorehabilitation is associated with shorter hospital stays and, as a result, reduced expenditure; this is true for both moderate and severe injuries.27,28

Although no specific timeframes are described in the literature, it is estimated that rehabilitation after ABI should begin within 24−48hours after injury, with simple actions such as early mobilisation, in the physical domain; and adaptation to the environment and orientation to reality, or management of such specific deficits as neglect or aphasia, in the cognitive domain.22 As the patient’s initial status improves, the intensity and content of rehabilitation should be increased; it has been suggested that the maximum time between injury and rehabilitation onset should be no longer than 3 weeks for moderate stroke and 4 weeks for severe stroke and moderate-severe TBI.27–29Table 4 shows the recommendations related to the time of rehabilitation onset and the corresponding grades of recommendation in the main guidelines reviewed.

- -

SENR recommendations:

- 1.

Rehabilitation treatment should be started as early as possible after stroke/TBI, once potentially life-threatening complications have been controlled, and always taking into account the characteristics of the intervention.

- 2.

With regard to mobility, given the special clinical relevance of complications derived from long periods of immobility, early mobilisation is recommended (stroke), although in patients with greater clinical severity, physical activity outside of the bed is not recommended in the first 24hours, including bed-chair transfers, standing, or walking.

- 3.

After the first 24hours, and preferably before the third day, expert assessment should establish the most appropriate and safest way to mobilise the patient, including short sessions repeated over the course of the day (stroke).

- 1.

When should patients receive neurorehabilitation? Summary of recommendations.

| Recommendations | Grade of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Stroke | |

| Acute phase (evaluation). All patients with acute stroke should undergo initial assessment by rehabilitation experts as soon as possible after admission. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (rehabilitation). All patients with stroke should start rehabilitation as early as deemed appropriate, providing that they are ready for this and are sufficiently stable from a medical perspective to participate actively in rehabilitation programmes. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (rehabilitation). Prolonged early mobilisation in the first days after stroke, especially in severe cases, is not recommended. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (rehabilitation). Rehabilitation should be started as soon as the patient is clinically stable. | HighStrong (VA-DOD) |

| Acute phase (motor rehabilitation). High-intensity early mobilisation is not recommended in the first 24hours after stroke, as it decreases the likelihood of favourable outcomes at 3 months. | HighA (AHA/ASA) |

| Acute phase (motor rehabilitation). Patients presenting mobility problems in the acute phase and who are medically stable should be offered frequent, short-duration mobilisation (sitting up in bed, standing, or walking) on a daily basis by trained professionals with access to the necessary equipment, typically starting between 24 and 48hours after stroke. Mobilisation in the first 24hours should only be performed in patients who need little or no assistance to move. | HighKey recommendation (RCP) |

| Chronic phase. All patients referred to a long-term care facility following stroke should initially be assessed by medical, nursing, and rehabilitation professionals, as soon as possible after admission. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase. Rehabilitation following intracranial haemorrhage can be beneficial provided it is started as early as possible and continued in the community as part of a well-coordinated early supported discharge programme, with the aim of promoting continuous recovery. | ModerateB (AHA/ASA) |

| Acute phase (motor rehabilitation). Intensive mobilisation out of bed is not recommended in the first 24hours after stroke in patients presenting limited mobility. | ModerateStrong, with low level of evidence (SF-CGSM) |

| Acute phase (motor rehabilitation). Patients with mild-moderate stroke should complete frequent, short sessions of mobilisations out of bed, although the optimum time in the first 48hours is unclear. | ModerateWeak grade of recommendation. High level of evidence (SF-CGSM) |

| Acute phase (motor rehabilitation). All patients with stroke and presenting no contraindication (palliative care) should start mobilisation out of bed within the first 48hours. | ModerateStrong, with low level of evidence (SF-CGSM) |

| Acute/subacute/chronic phases. At the time of treatment onset, regardless of the clinical phase and the treatment facility, planning should begin for the transition to future stages of healthcare. | ModerateC (CSBPR) |

| Subacute/chronic phases. Patients with stroke and their families and caregivers should be prepared in advance to ensure success in the different treatment stages and settings they will pass through over the course of rehabilitation. To that end, they should be provided with information and training materials, offered psychosocial support, and informed and assisted as needed in order to access community services and resources. This support should begin at the time of stroke and continue throughout the rehabilitation process, independently of their clinical status or the healthcare facility where the intervention takes place. | ModerateC (CSBPR) |

| Acute/subacute/chronic phases. All patients with stroke and their families and caregivers should be assessed to establish their capacity to cope with their new circumstances, the risk of depression, and other physical or psychological problems. Ideally, screening should be conducted after each change or care transition, and whenever considered necessary by the professional responsible for the patient. | ModerateC (CSBPR) |

| Chronic phase. Patients with stroke and their families and caregivers should be given information, education, training, support, and access to the services needed when the patient returns to the community, in order to achieve the greatest possible level of social activity and participation. | ModerateC (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (evaluation). Screening tests should be performed to establish the need for follow-up of residual deficits and formal rehabilitation needs in all patients with acute stroke or TIA who are not admitted to hospital, before they leave the emergency department or healthcare centre. As a priority, this screening should address the patient’s capacities (cognition, ability to drive, etc), swallowing, communication, and mobility, and should be conducted by an expert in stroke rehabilitation. At 2 weeks, additional screening should be conducted, which should include potential cognitive deficits, functional activity limitations, participation restrictions, environmental factors, modifiable risk factors (lifestyle), and depressive symptoms. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (evaluation). The potential rehabilitation needs of all patients not initially meeting criteria for rehabilitation should be re-evaluated on a weekly basis for the first month, with subsequent periodic re-evaluation in accordance with their health status. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (evaluation). Initial screening and evaluation should be performed within the first 48hours after admission, by rehabilitation professionals in direct contact with the patient. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (rehabilitation). Early mobilisation may be performed in some patients (mild stroke or TIA), under strict clinical supervision. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (evaluation). The interprofessional rehabilitation team should evaluate patients within the first 48hours after admission and, in collaboration with the patient and their family, draft an individual comprehensive rehabilitation plan in accordance with stroke severity, patient needs and objectives, the best available evidence, and the rehabilitation team’s clinical experience. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase (rehabilitation). All patients with stroke should receive rehabilitation therapy as soon as possible, once the patient is considered ready and able to participate in rehabilitation. | LowIV (UEMS-PRM) |

| Acute phase (motor rehabilitation). Early mobilisation (in the first 24−48hours) improves functional outcomes. | LowInsufficient evidence (VA-DOD) |

| TBI | |

| Acute phase. The rehabilitation process should be started as early as possible after acute trauma, preferably at the intensive care unit, as soon as the patient’s clinical status allows for acute rehabilitation. | HighI (UEMS-PRMS) |

| Acute phase. Rehabilitation interventions in patients with TBI should begin as soon as their clinical condition allows. | ModeratePriority B (INESSS-ONF) |

| Brain damage | |

| Acute phase. Neurorehabilitation treatment and/or each component of this treatment should be started as early as possible, taking into account the nature of the intervention and the patient’s ability to cooperate with treatment. In any case, treatment should be started within 6 months after injury, wherever possible. | HighA (IMSERSO) |

| Acute phase. For optimal results, rehabilitation must be intense, started early, and delivered by specialised, multidisciplinary teams. | ModerateB (SIGN) |

AHA/ASA: American Heart Association-American Stroke Association; CSBPR: Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Stroke Rehabilitation Practice Guidelines; IMSERSO: Instituto de Migraciones y Servicios Sociales – Fundación Reintegra; INESSS-ONF: Institut National d’Excellence en Santé et en Services Sociaux – Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; SF-CGSM: Stroke Foundation - Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management; SIGN: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; TBI: traumatic brain injury; TIA: transient ischaemic attack; UEMS-PRMS: European Union of Medical Specialists-Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine Section; VA-DOD: Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Stroke Rehabilitation. Department of Veterans Affairs-Department of Defense.

All recent studies in the field of rehabilitation agree that the number of hours of treatment per day is clearly predictive of the final functional outcome.30,31 Treatment intensity has been directly associated with both the magnitude and the speed of patients’ physical, cognitive, and functional recovery, in both the short and the long term.30–39 Several studies have suggested a cut-off point of at least 3hours of treatment per day.40–43 When assessing the influence of treatment intensity on the benefit of the treatment applied, it should be noted that the majority of studies consider time in therapy to be the closest correlate of treatment intensity; however, “time in therapy” clearly does not mean the same as “time spent performing a therapeutic activity.” Most studies generally focus on motor aspects, such as global mobility, ability to walk, or upper limb use. No evidence has been reported to date that patients with more symptoms of fatigue or with greater cognitive difficulties do not benefit from this time planning and structure, although their tolerance to certain intensive treatments may not be optimal. In patients with more severe cognitive involvement, certain strategies can be employed to maximise time in treatment, increasing tolerance and treatment duration. The most frequently used environmental changes include removing distractors, simplifying instructions, reducing the amount of information provided, or fractionating therapy with the introduction of more frequent rests.44Table 5 shows the recommendations related to rehabilitation treatment intensity and the corresponding grades of recommendation in the main guidelines reviewed.

- -

SENR recommendations:

- 1.

Rehabilitation programmes should be structured to offer, at all times, the greatest possible frequency, duration, and intensity of treatment, understood as the time dedicated to the task, always taking into account the needs and objectives of the rehabilitation team.

- 2.

CPGs currently recommend at least 45–60minutes of each type of therapy needed (e.g, speech therapy, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, neuropsychology), in accordance with patient needs (typically 3hours/day), at a frequency that enables the patient to achieve their rehabilitation objectives (typically, 5 days per week). If further rehabilitation is needed at a later time, its intensity should be adapted to patient needs at all times.

- 1.

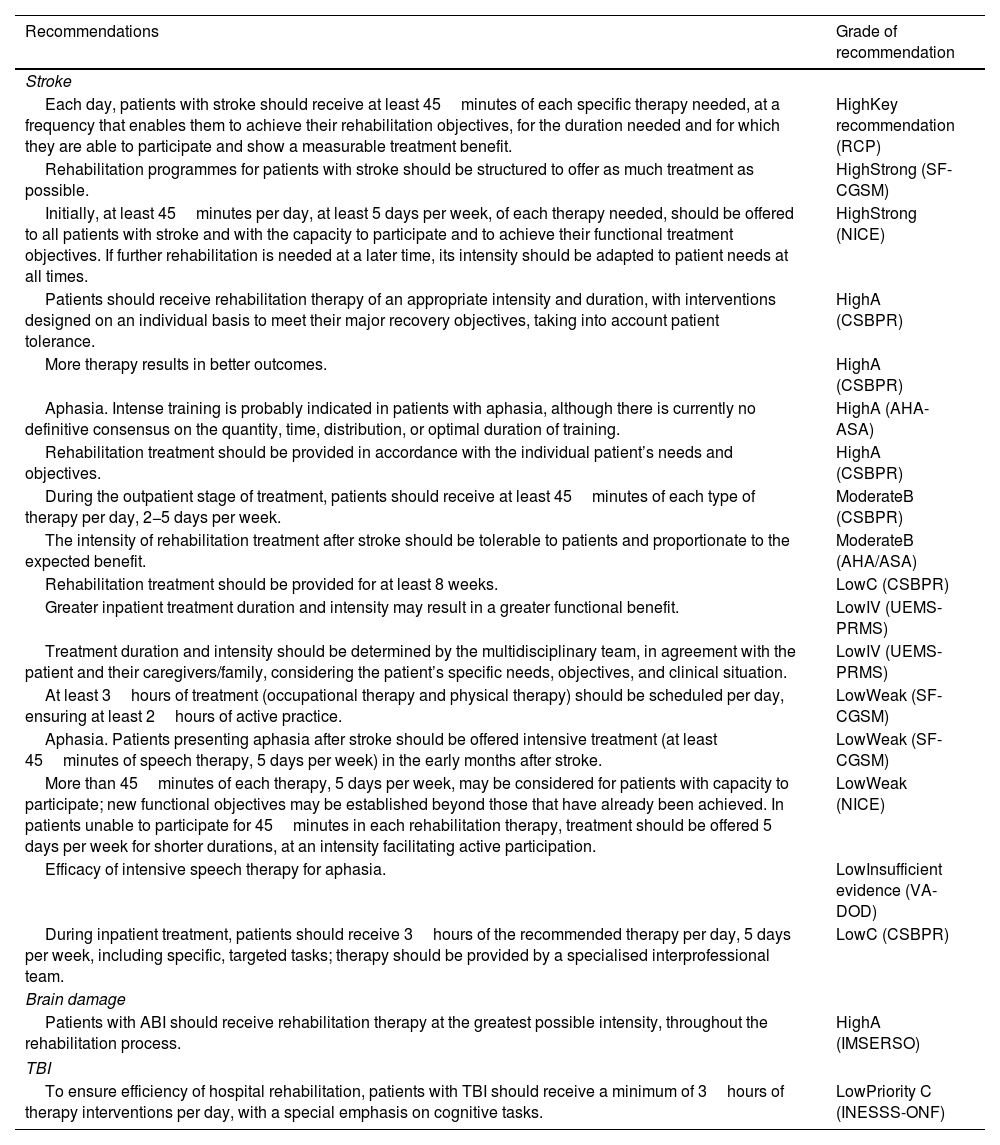

How much treatment should be provided? Summary of recommendations.

| Recommendations | Grade of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Stroke | |

| Each day, patients with stroke should receive at least 45minutes of each specific therapy needed, at a frequency that enables them to achieve their rehabilitation objectives, for the duration needed and for which they are able to participate and show a measurable treatment benefit. | HighKey recommendation (RCP) |

| Rehabilitation programmes for patients with stroke should be structured to offer as much treatment as possible. | HighStrong (SF-CGSM) |

| Initially, at least 45minutes per day, at least 5 days per week, of each therapy needed, should be offered to all patients with stroke and with the capacity to participate and to achieve their functional treatment objectives. If further rehabilitation is needed at a later time, its intensity should be adapted to patient needs at all times. | HighStrong (NICE) |

| Patients should receive rehabilitation therapy of an appropriate intensity and duration, with interventions designed on an individual basis to meet their major recovery objectives, taking into account patient tolerance. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| More therapy results in better outcomes. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Aphasia. Intense training is probably indicated in patients with aphasia, although there is currently no definitive consensus on the quantity, time, distribution, or optimal duration of training. | HighA (AHA-ASA) |

| Rehabilitation treatment should be provided in accordance with the individual patient’s needs and objectives. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| During the outpatient stage of treatment, patients should receive at least 45minutes of each type of therapy per day, 2−5 days per week. | ModerateB (CSBPR) |

| The intensity of rehabilitation treatment after stroke should be tolerable to patients and proportionate to the expected benefit. | ModerateB (AHA/ASA) |

| Rehabilitation treatment should be provided for at least 8 weeks. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Greater inpatient treatment duration and intensity may result in a greater functional benefit. | LowIV (UEMS-PRMS) |

| Treatment duration and intensity should be determined by the multidisciplinary team, in agreement with the patient and their caregivers/family, considering the patient’s specific needs, objectives, and clinical situation. | LowIV (UEMS-PRMS) |

| At least 3hours of treatment (occupational therapy and physical therapy) should be scheduled per day, ensuring at least 2hours of active practice. | LowWeak (SF-CGSM) |

| Aphasia. Patients presenting aphasia after stroke should be offered intensive treatment (at least 45minutes of speech therapy, 5 days per week) in the early months after stroke. | LowWeak (SF-CGSM) |

| More than 45minutes of each therapy, 5 days per week, may be considered for patients with capacity to participate; new functional objectives may be established beyond those that have already been achieved. In patients unable to participate for 45minutes in each rehabilitation therapy, treatment should be offered 5 days per week for shorter durations, at an intensity facilitating active participation. | LowWeak (NICE) |

| Efficacy of intensive speech therapy for aphasia. | LowInsufficient evidence (VA-DOD) |

| During inpatient treatment, patients should receive 3hours of the recommended therapy per day, 5 days per week, including specific, targeted tasks; therapy should be provided by a specialised interprofessional team. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Brain damage | |

| Patients with ABI should receive rehabilitation therapy at the greatest possible intensity, throughout the rehabilitation process. | HighA (IMSERSO) |

| TBI | |

| To ensure efficiency of hospital rehabilitation, patients with TBI should receive a minimum of 3hours of therapy interventions per day, with a special emphasis on cognitive tasks. | LowPriority C (INESSS-ONF) |

ABI: acquired brain injury; AHA/ASA: American Heart Association-American Stroke Association; CSBPR: Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Stroke Rehabilitation Practice Guidelines; IMSERSO: Instituto de Migraciones y Servicios Sociales – Fundación Reintegra; INESSS-ONF: Institut National d’Excellence en Santé et en Services Sociaux – Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; SF-CGSM: Stroke Foundation – Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management; TBI: traumatic brain injury; UEMS-PRMS: European Union of Medical Specialists-Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine Section; VA-DOD: Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Stroke Rehabilitation. Department of Veterans Affairs-Department of Defense.

With regard to the rehabilitation team, all guidelines for rehabilitation after ABI consider it necessary for therapy to be provided by multidisciplinary teams including, at least: physicians specialised in caring for patients with brain injury, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, neuropsychologists, and social workers. Furthermore, therapy should be provided in specific spaces dedicated to this treatment, with access to other services (e.g, orthopaedics, pharmacy, nutrition), and a multidisciplinary education programme for patients’ families.45

This multidisciplinary approach requires that patients be assessed by all members of the team, with a view to developing a common treatment approach with objectives that are coordinated, precise, measurable, relevant, realistic, and achievable. The holistic approach and other comprehensive treatment approaches are characterised by considerable structuring and integration of interventions in different domains (cognitive, emotional, functional, physical, social, etc); this requires intensive coordination between all members of the transdisciplinary team, the patient, and their family.46–49 These approaches have been shown to be more effective than multidisciplinary treatment that is less structured and coordinated (but with similar rehabilitation team composition and treatment times). Table 6 shows the recommendations related to rehabilitation team composition and the corresponding grades of recommendation in the main guidelines reviewed.

- -

SENR recommendations:

- 1.

Regardless of the care setting, patients with ABI should have access to assessment and treatment by an organised, coordinated transdisciplinary team equipped with the knowledge, experience, and skills required to work in collaboration with patients with ABI and their families. Teams should include, at least, physicians (physiatrist, neurologist, and other physicians with experience in rehabilitation after ABI), nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, neuropsychologists, and social workers.

- 2.

Teams may benefit from the support of a dietitian, orthopaedist, pharmacist, care assistants, pedagogists, recreational and vocational therapy specialists, rehabilitation engineers, and any other specialist required to achieve specific treatment objectives.

- 3.

The team should be able to address any physical, cognitive/behavioural, or social problems (structure-function-activity and participation) that patients may present over the course of their recovery.

- 1.

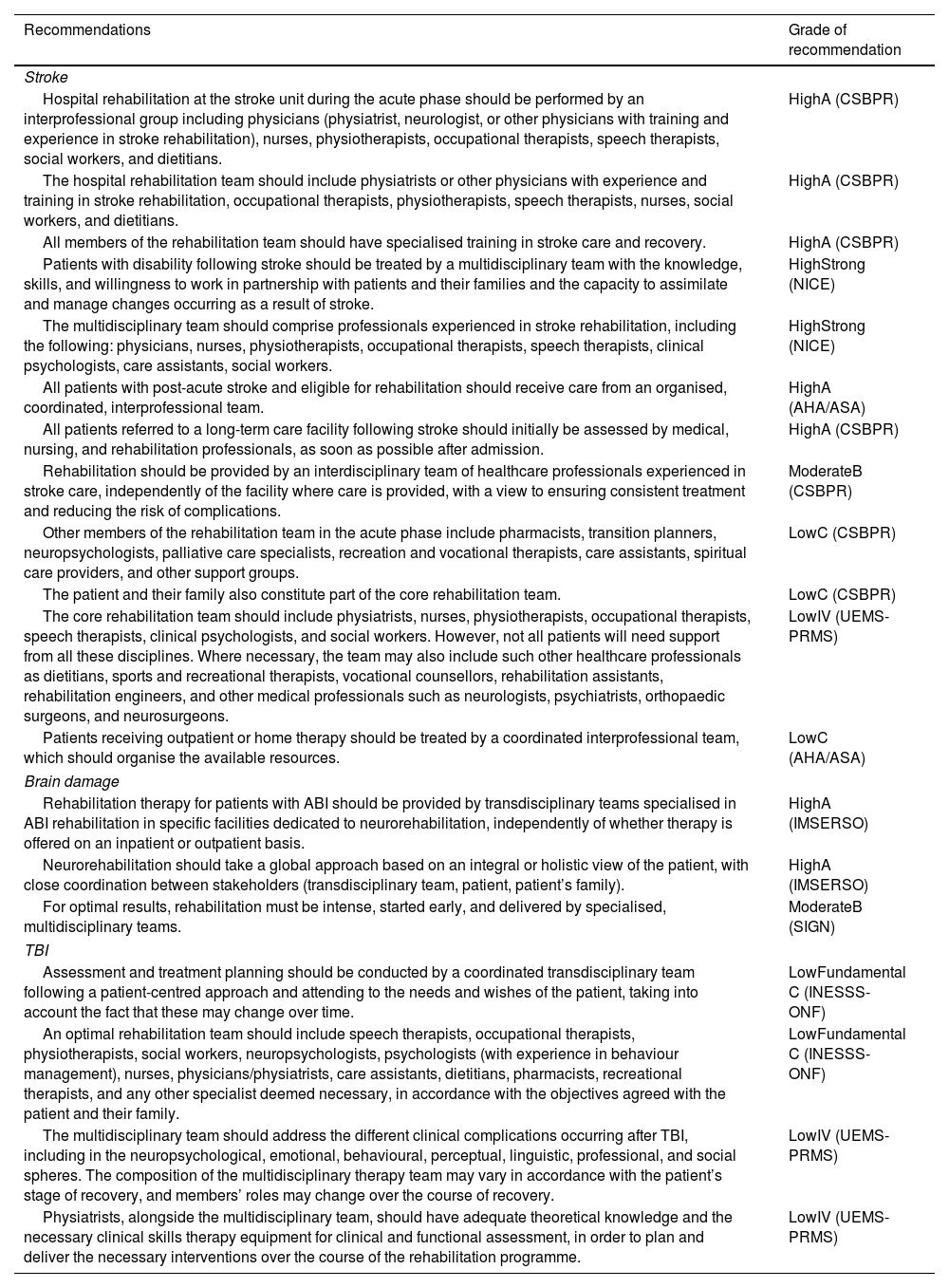

Who should provide neurorehabilitation treatment? Summary of recommendations.

| Recommendations | Grade of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Stroke | |

| Hospital rehabilitation at the stroke unit during the acute phase should be performed by an interprofessional group including physicians (physiatrist, neurologist, or other physicians with training and experience in stroke rehabilitation), nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, social workers, and dietitians. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| The hospital rehabilitation team should include physiatrists or other physicians with experience and training in stroke rehabilitation, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech therapists, nurses, social workers, and dietitians. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| All members of the rehabilitation team should have specialised training in stroke care and recovery. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Patients with disability following stroke should be treated by a multidisciplinary team with the knowledge, skills, and willingness to work in partnership with patients and their families and the capacity to assimilate and manage changes occurring as a result of stroke. | HighStrong (NICE) |

| The multidisciplinary team should comprise professionals experienced in stroke rehabilitation, including the following: physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, clinical psychologists, care assistants, social workers. | HighStrong (NICE) |

| All patients with post-acute stroke and eligible for rehabilitation should receive care from an organised, coordinated, interprofessional team. | HighA (AHA/ASA) |

| All patients referred to a long-term care facility following stroke should initially be assessed by medical, nursing, and rehabilitation professionals, as soon as possible after admission. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Rehabilitation should be provided by an interdisciplinary team of healthcare professionals experienced in stroke care, independently of the facility where care is provided, with a view to ensuring consistent treatment and reducing the risk of complications. | ModerateB (CSBPR) |

| Other members of the rehabilitation team in the acute phase include pharmacists, transition planners, neuropsychologists, palliative care specialists, recreation and vocational therapists, care assistants, spiritual care providers, and other support groups. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| The patient and their family also constitute part of the core rehabilitation team. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| The core rehabilitation team should include physiatrists, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, clinical psychologists, and social workers. However, not all patients will need support from all these disciplines. Where necessary, the team may also include such other healthcare professionals as dietitians, sports and recreational therapists, vocational counsellors, rehabilitation assistants, rehabilitation engineers, and other medical professionals such as neurologists, psychiatrists, orthopaedic surgeons, and neurosurgeons. | LowIV (UEMS-PRMS) |

| Patients receiving outpatient or home therapy should be treated by a coordinated interprofessional team, which should organise the available resources. | LowC (AHA/ASA) |

| Brain damage | |

| Rehabilitation therapy for patients with ABI should be provided by transdisciplinary teams specialised in ABI rehabilitation in specific facilities dedicated to neurorehabilitation, independently of whether therapy is offered on an inpatient or outpatient basis. | HighA (IMSERSO) |

| Neurorehabilitation should take a global approach based on an integral or holistic view of the patient, with close coordination between stakeholders (transdisciplinary team, patient, patient’s family). | HighA (IMSERSO) |

| For optimal results, rehabilitation must be intense, started early, and delivered by specialised, multidisciplinary teams. | ModerateB (SIGN) |

| TBI | |

| Assessment and treatment planning should be conducted by a coordinated transdisciplinary team following a patient-centred approach and attending to the needs and wishes of the patient, taking into account the fact that these may change over time. | LowFundamental C (INESSS-ONF) |

| An optimal rehabilitation team should include speech therapists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, social workers, neuropsychologists, psychologists (with experience in behaviour management), nurses, physicians/physiatrists, care assistants, dietitians, pharmacists, recreational therapists, and any other specialist deemed necessary, in accordance with the objectives agreed with the patient and their family. | LowFundamental C (INESSS-ONF) |

| The multidisciplinary team should address the different clinical complications occurring after TBI, including in the neuropsychological, emotional, behavioural, perceptual, linguistic, professional, and social spheres. The composition of the multidisciplinary therapy team may vary in accordance with the patient’s stage of recovery, and members’ roles may change over the course of recovery. | LowIV (UEMS-PRMS) |

| Physiatrists, alongside the multidisciplinary team, should have adequate theoretical knowledge and the necessary clinical skills therapy equipment for clinical and functional assessment, in order to plan and deliver the necessary interventions over the course of the rehabilitation programme. | LowIV (UEMS-PRMS) |

ABI: acquired brain injury; AHA/ASA: American Heart Association-American Stroke Association; CSBPR: Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Stroke Rehabilitation Practice Guidelines; ABI: acquired brain injury; IMSERSO: Instituto de Migraciones y Servicios Sociales-Fundación Reintegra; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; INESSS-ONF: Institut National d’Excellence en Santé et en Services Sociaux – Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; SIGN: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; TBI: traumatic brain injury; UEMS-PRMS: European Union of Medical Specialists – Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine Section.

Patients with ABI may require both inpatient and outpatient treatment. The selection of one or the other form of treatment depends on the rehabilitation needs established according to the guidelines described above, and the clinical severity of the patient. With respect to inpatient care, the guidelines reviewed present a high degree of consensus on the recommendation that specialised stroke units, with multidisciplinary teams specialised in stroke care, are more effective than general hospital wards or residential or other tertiary-level healthcare centres.45 Some European countries, with organised outpatient services, have developed models with short hospitalisation times and early supported discharge for patients with sufficiently good functional status (chair-bed transfers performed independently or with assistance, as long as the environment and assistant promote safety and confidence).50 In these systems, early discharge and transfer to outpatient care is understood as a process that promotes the independence of patients in their environment, without detriment to rehabilitation needs (intensity, constancy, frequency).51 If, as a result of the lack of resources or clinical severity, these requirements cannot be guaranteed, it is preferable to continue treatment on an inpatient basis.

Outpatient treatment ensures continuity of care, and therefore may offer additional benefits to many patients who are discharged from acute care or who, having benefited from specialised care at neurorehabilitation centres, need to continue treatment on an outpatient basis. This type of treatment can be offered via multiple healthcare resources (hospitals with outpatient programmes, day centres, community care programmes, home care programmes, etc). Most studies comparing these diverse services have found no differences, providing that they ensure similar content, intensity, and organisation; however, patients with more severe ABI seem to benefit more from inpatient care.52 For practical purposes, guidelines recommend continued treatment on an outpatient basis in the 24−72hours after hospital discharge in patients requiring this care, following the care plan established by the rehabilitation team. For this reason, it is advisable to maintain continuity of the treatment team during the transition from hospital to outpatient care.53 Despite the uniformity of care provision, this model requires an extensive network of services both for treatment and for assessment, across the health system, including the knowledge and use of scales by all professionals in contact with potentially eligible patients, the creation of bodies to regulate access to rehabilitation, etc. Table 7 includes the recommendations related to the context in which rehabilitation programmes should be delivered and the corresponding grade of recommendation in the main guidelines reviewed.

- -

SENR recommendations:

- 1.

Once the patient with ABI has been assessed and their rehabilitation needs determined, the most appropriate context for rehabilitation must be established (inpatient care, outpatient care, home rehabilitation, community rehabilitation).

- 2.

During the acute phase, and in the most severe cases, intensive, multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes at hospital units are recommended.

- 3.

The transition to the outpatient setting must guarantee continuity in time (24−72hours) and in the knowledge accumulated during the inpatient phase (same treatment team, or close cooperation between teams), and should be made as early as possible, providing that the patient’s clinical status permits this, that treatment intensity can be maintained in accordance with the pre-established treatment objectives, and that care quality can be guaranteed in the patient’s social or family setting.

- 4.

Outpatient treatment should offer the same structure and content as inpatient care.

- 1.

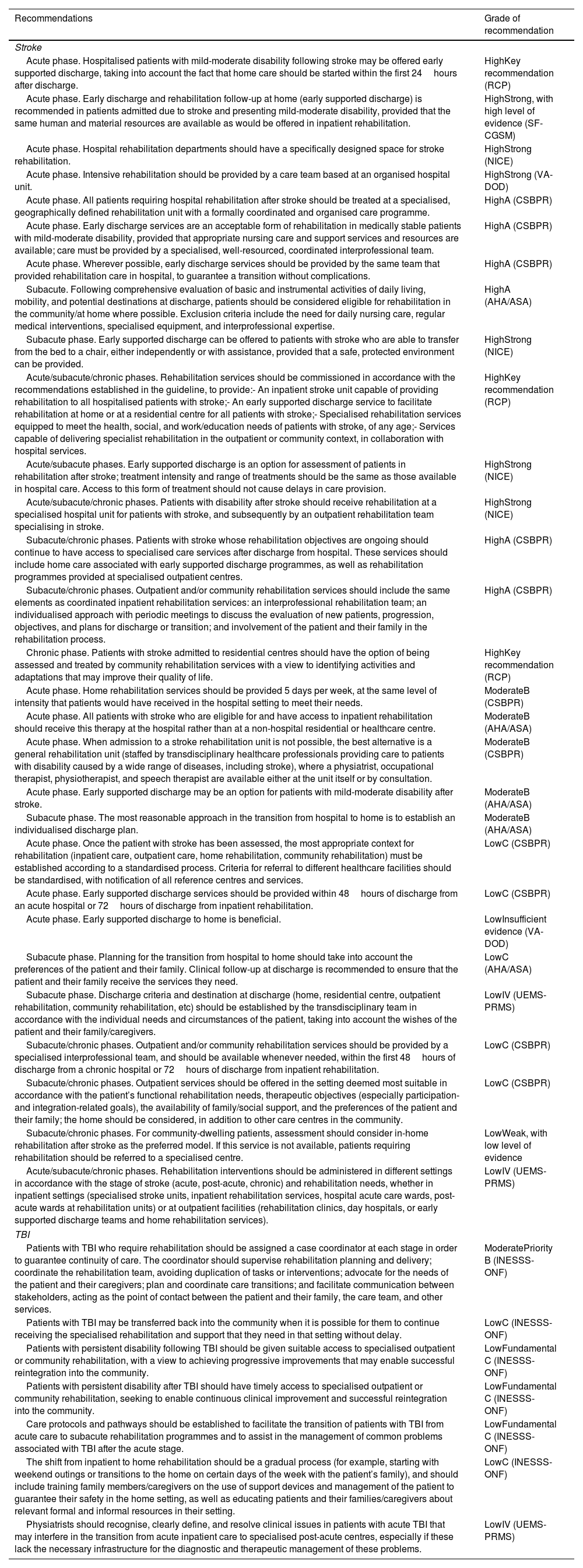

Where should neurorehabilitation treatment be provided? Summary of recommendations.

| Recommendations | Grade of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Stroke | |

| Acute phase. Hospitalised patients with mild-moderate disability following stroke may be offered early supported discharge, taking into account the fact that home care should be started within the first 24hours after discharge. | HighKey recommendation (RCP) |

| Acute phase. Early discharge and rehabilitation follow-up at home (early supported discharge) is recommended in patients admitted due to stroke and presenting mild-moderate disability, provided that the same human and material resources are available as would be offered in inpatient rehabilitation. | HighStrong, with high level of evidence (SF-CGSM) |

| Acute phase. Hospital rehabilitation departments should have a specifically designed space for stroke rehabilitation. | HighStrong (NICE) |

| Acute phase. Intensive rehabilitation should be provided by a care team based at an organised hospital unit. | HighStrong (VA-DOD) |

| Acute phase. All patients requiring hospital rehabilitation after stroke should be treated at a specialised, geographically defined rehabilitation unit with a formally coordinated and organised care programme. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase. Early discharge services are an acceptable form of rehabilitation in medically stable patients with mild-moderate disability, provided that appropriate nursing care and support services and resources are available; care must be provided by a specialised, well-resourced, coordinated interprofessional team. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase. Wherever possible, early discharge services should be provided by the same team that provided rehabilitation care in hospital, to guarantee a transition without complications. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Subacute. Following comprehensive evaluation of basic and instrumental activities of daily living, mobility, and potential destinations at discharge, patients should be considered eligible for rehabilitation in the community/at home where possible. Exclusion criteria include the need for daily nursing care, regular medical interventions, specialised equipment, and interprofessional expertise. | HighA (AHA/ASA) |

| Subacute phase. Early supported discharge can be offered to patients with stroke who are able to transfer from the bed to a chair, either independently or with assistance, provided that a safe, protected environment can be provided. | HighStrong (NICE) |

| Acute/subacute/chronic phases. Rehabilitation services should be commissioned in accordance with the recommendations established in the guideline, to provide:- An inpatient stroke unit capable of providing rehabilitation to all hospitalised patients with stroke;- An early supported discharge service to facilitate rehabilitation at home or at a residential centre for all patients with stroke;- Specialised rehabilitation services equipped to meet the health, social, and work/education needs of patients with stroke, of any age;- Services capable of delivering specialist rehabilitation in the outpatient or community context, in collaboration with hospital services. | HighKey recommendation (RCP) |

| Acute/subacute phases. Early supported discharge is an option for assessment of patients in rehabilitation after stroke; treatment intensity and range of treatments should be the same as those available in hospital care. Access to this form of treatment should not cause delays in care provision. | HighStrong (NICE) |

| Acute/subacute/chronic phases. Patients with disability after stroke should receive rehabilitation at a specialised hospital unit for patients with stroke, and subsequently by an outpatient rehabilitation team specialising in stroke. | HighStrong (NICE) |

| Subacute/chronic phases. Patients with stroke whose rehabilitation objectives are ongoing should continue to have access to specialised care services after discharge from hospital. These services should include home care associated with early supported discharge programmes, as well as rehabilitation programmes provided at specialised outpatient centres. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Subacute/chronic phases. Outpatient and/or community rehabilitation services should include the same elements as coordinated inpatient rehabilitation services: an interprofessional rehabilitation team; an individualised approach with periodic meetings to discuss the evaluation of new patients, progression, objectives, and plans for discharge or transition; and involvement of the patient and their family in the rehabilitation process. | HighA (CSBPR) |

| Chronic phase. Patients with stroke admitted to residential centres should have the option of being assessed and treated by community rehabilitation services with a view to identifying activities and adaptations that may improve their quality of life. | HighKey recommendation (RCP) |

| Acute phase. Home rehabilitation services should be provided 5 days per week, at the same level of intensity that patients would have received in the hospital setting to meet their needs. | ModerateB (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase. All patients with stroke who are eligible for and have access to inpatient rehabilitation should receive this therapy at the hospital rather than at a non-hospital residential or healthcare centre. | ModerateB (AHA/ASA) |

| Acute phase. When admission to a stroke rehabilitation unit is not possible, the best alternative is a general rehabilitation unit (staffed by transdisciplinary healthcare professionals providing care to patients with disability caused by a wide range of diseases, including stroke), where a physiatrist, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, and speech therapist are available either at the unit itself or by consultation. | ModerateB (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase. Early supported discharge may be an option for patients with mild-moderate disability after stroke. | ModerateB (AHA/ASA) |

| Subacute phase. The most reasonable approach in the transition from hospital to home is to establish an individualised discharge plan. | ModerateB (AHA/ASA) |

| Acute phase. Once the patient with stroke has been assessed, the most appropriate context for rehabilitation (inpatient care, outpatient care, home rehabilitation, community rehabilitation) must be established according to a standardised process. Criteria for referral to different healthcare facilities should be standardised, with notification of all reference centres and services. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase. Early supported discharge services should be provided within 48hours of discharge from an acute hospital or 72hours of discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Acute phase. Early supported discharge to home is beneficial. | LowInsufficient evidence (VA-DOD) |

| Subacute phase. Planning for the transition from hospital to home should take into account the preferences of the patient and their family. Clinical follow-up at discharge is recommended to ensure that the patient and their family receive the services they need. | LowC (AHA/ASA) |

| Subacute phase. Discharge criteria and destination at discharge (home, residential centre, outpatient rehabilitation, community rehabilitation, etc) should be established by the transdisciplinary team in accordance with the individual needs and circumstances of the patient, taking into account the wishes of the patient and their family/caregivers. | LowIV (UEMS-PRMS) |

| Subacute/chronic phases. Outpatient and/or community rehabilitation services should be provided by a specialised interprofessional team, and should be available whenever needed, within the first 48hours of discharge from a chronic hospital or 72hours of discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Subacute/chronic phases. Outpatient services should be offered in the setting deemed most suitable in accordance with the patient’s functional rehabilitation needs, therapeutic objectives (especially participation- and integration-related goals), the availability of family/social support, and the preferences of the patient and their family; the home should be considered, in addition to other care centres in the community. | LowC (CSBPR) |

| Subacute/chronic phases. For community-dwelling patients, assessment should consider in-home rehabilitation after stroke as the preferred model. If this service is not available, patients requiring rehabilitation should be referred to a specialised centre. | LowWeak, with low level of evidence |

| Acute/subacute/chronic phases. Rehabilitation interventions should be administered in different settings in accordance with the stage of stroke (acute, post-acute, chronic) and rehabilitation needs, whether in inpatient settings (specialised stroke units, inpatient rehabilitation services, hospital acute care wards, post-acute wards at rehabilitation units) or at outpatient facilities (rehabilitation clinics, day hospitals, or early supported discharge teams and home rehabilitation services). | LowIV (UEMS-PRMS) |

| TBI | |

| Patients with TBI who require rehabilitation should be assigned a case coordinator at each stage in order to guarantee continuity of care. The coordinator should supervise rehabilitation planning and delivery; coordinate the rehabilitation team, avoiding duplication of tasks or interventions; advocate for the needs of the patient and their caregivers; plan and coordinate care transitions; and facilitate communication between stakeholders, acting as the point of contact between the patient and their family, the care team, and other services. | ModeratePriority B (INESSS-ONF) |

| Patients with TBI may be transferred back into the community when it is possible for them to continue receiving the specialised rehabilitation and support that they need in that setting without delay. | LowC (INESSS-ONF) |

| Patients with persistent disability following TBI should be given suitable access to specialised outpatient or community rehabilitation, with a view to achieving progressive improvements that may enable successful reintegration into the community. | LowFundamental C (INESSS-ONF) |

| Patients with persistent disability after TBI should have timely access to specialised outpatient or community rehabilitation, seeking to enable continuous clinical improvement and successful reintegration into the community. | LowFundamental C (INESSS-ONF) |

| Care protocols and pathways should be established to facilitate the transition of patients with TBI from acute care to subacute rehabilitation programmes and to assist in the management of common problems associated with TBI after the acute stage. | LowFundamental C (INESSS-ONF) |

| The shift from inpatient to home rehabilitation should be a gradual process (for example, starting with weekend outings or transitions to the home on certain days of the week with the patient’s family), and should include training family members/caregivers on the use of support devices and management of the patient to guarantee their safety in the home setting, as well as educating patients and their families/caregivers about relevant formal and informal resources in their setting. | LowC (INESSS-ONF) |

| Physiatrists should recognise, clearly define, and resolve clinical issues in patients with acute TBI that may interfere in the transition from acute inpatient care to specialised post-acute centres, especially if these lack the necessary infrastructure for the diagnostic and therapeutic management of these problems. | LowIV (UEMS-PRMS) |

AHA/ASA: American Heart Association-American Stroke Association; CSBPR: Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Stroke Rehabilitation Practice Guidelines; IMSERSO: Instituto de Migraciones y Servicios Sociales – Fundación Reintegra; INESSS-ONF: Institut National d’Excellence en Santé et en Services Sociaux – Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; RCP: Royal College of Physicians; SF-CGSM: Stroke Foundation – Clinical Guidelines for Stroke; TBI: traumatic brain injury; UEMS-PRMS: European Union of Medical Specialists – Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine Section.

The conceptual model of ABI has changed in line with current evidence, and it is now understood as a chronic health issue with long-term repercussions, rather than as an incidental occurrence.54–56 In fact, after the initial period of recovery facilitated by rehabilitation, disability secondary to ABI tends to follow a progressive course, with a gradual increase in physical, cognitive, behavioural, and emotional complications over the years following the injury; this results in a clear decrease in life expectancy and quality in these patients.39,57 Some authors report that 3% of patients with stroke deteriorate to dependency each year, reaching 10%–18% at 5 years.50,58–60 A similar loss of functional capacity over the years is described in patients with TBI. In addition to this loss of independence, these diseases have a clear impact on patients’ health throughout their lives. Numerous studies have shown that patients with ABI present increased risk of epilepsy, sleep disorders, neuroendocrine problems, depression and other psychiatric disorders, cognitive impairment, and dementia and other neurodegenerative processes.55,61,62

Furthermore, the classical idea during the 1990s that clinical stabilisation after stroke occurs at 3–6 months63 has evolved in line with the implementation and generalisation of multidisciplinary rehabilitation systems; new technologies available today have enabled the intensification and prolongation of treatment.64 We now know that recovery after ABI does not follow a linear path, and that while recovery of deficits resulting from these injuries slows over time, stabilisation (termed the plateau in the literature) seems to extend beyond the first months.65,66 Populations of patients undergoing rehabilitation programmes and assessed with appropriate scales seem to show improvements in deficits, activity, social participation, and quality of life, even years after the initial injury.33,67,68 The previously reported reduction in some of the gains made appears to be related to the methodological characteristics of some studies, particularly with respect to population characteristics or the measurements used, treatment intensity, the complex patient-therapist interaction, and other structural factors, as well as potential adaptation mechanisms, etc.64,69

Finally, we must bear in mind the fact that, for many patients participating in rehabilitation programmes, their rehabilitation needs are not met when they are assessed years after the event that caused ABI.70 In fact, a high percentage of patients with ABI who are considered to have recovered well continue to present cognitive/behavioural problems that limit their participation in the family, social, and work settings.71 The neurorehabilitation paradigm must take into account the fact that treating a deficit is only meaningful if it enables rehabilitation of the patient. However, it is striking that even today, only 2% of trials on acute stroke and 6% of trials on stroke rehabilitation analyse limitations in participation. Table 8 shows the recommendations related to rehabilitation programme duration and the corresponding levels of evidence in the main guidelines reviewed.

- -

SENR recommendations:

- 1.

Rehabilitation programmes should not be subject to time limitations; rather, they should take into account treatment response and the likelihood of improvement according to the best available evidence and the professional judgement of the rehabilitation team.

- 2.

After discharge, patients should be offered health promotion services, physical activity, support, and long-term follow-up to ensure that benefits are maintained, to detect potential medical complications, and to assess potential changes in functional status or level of dependence that require access to new treatment programmes.

- 1.

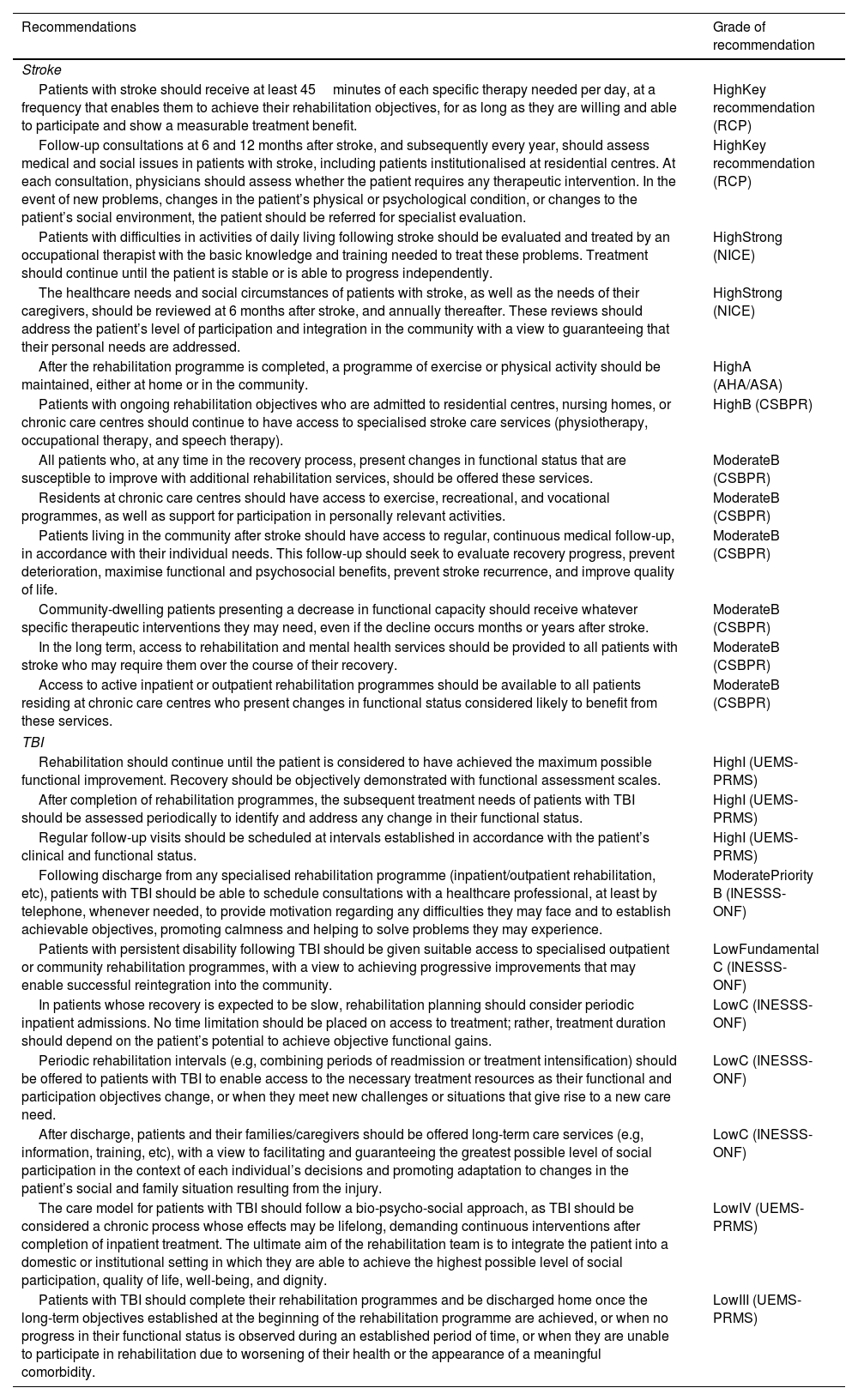

For how long should care be provided? Summary of recommendations.

| Recommendations | Grade of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Stroke | |

| Patients with stroke should receive at least 45minutes of each specific therapy needed per day, at a frequency that enables them to achieve their rehabilitation objectives, for as long as they are willing and able to participate and show a measurable treatment benefit. | HighKey recommendation (RCP) |

| Follow-up consultations at 6 and 12 months after stroke, and subsequently every year, should assess medical and social issues in patients with stroke, including patients institutionalised at residential centres. At each consultation, physicians should assess whether the patient requires any therapeutic intervention. In the event of new problems, changes in the patient’s physical or psychological condition, or changes to the patient’s social environment, the patient should be referred for specialist evaluation. | HighKey recommendation (RCP) |

| Patients with difficulties in activities of daily living following stroke should be evaluated and treated by an occupational therapist with the basic knowledge and training needed to treat these problems. Treatment should continue until the patient is stable or is able to progress independently. | HighStrong (NICE) |

| The healthcare needs and social circumstances of patients with stroke, as well as the needs of their caregivers, should be reviewed at 6 months after stroke, and annually thereafter. These reviews should address the patient’s level of participation and integration in the community with a view to guaranteeing that their personal needs are addressed. | HighStrong (NICE) |

| After the rehabilitation programme is completed, a programme of exercise or physical activity should be maintained, either at home or in the community. | HighA (AHA/ASA) |

| Patients with ongoing rehabilitation objectives who are admitted to residential centres, nursing homes, or chronic care centres should continue to have access to specialised stroke care services (physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy). | HighB (CSBPR) |

| All patients who, at any time in the recovery process, present changes in functional status that are susceptible to improve with additional rehabilitation services, should be offered these services. | ModerateB (CSBPR) |

| Residents at chronic care centres should have access to exercise, recreational, and vocational programmes, as well as support for participation in personally relevant activities. | ModerateB (CSBPR) |

| Patients living in the community after stroke should have access to regular, continuous medical follow-up, in accordance with their individual needs. This follow-up should seek to evaluate recovery progress, prevent deterioration, maximise functional and psychosocial benefits, prevent stroke recurrence, and improve quality of life. | ModerateB (CSBPR) |

| Community-dwelling patients presenting a decrease in functional capacity should receive whatever specific therapeutic interventions they may need, even if the decline occurs months or years after stroke. | ModerateB (CSBPR) |

| In the long term, access to rehabilitation and mental health services should be provided to all patients with stroke who may require them over the course of their recovery. | ModerateB (CSBPR) |

| Access to active inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation programmes should be available to all patients residing at chronic care centres who present changes in functional status considered likely to benefit from these services. | ModerateB (CSBPR) |

| TBI | |

| Rehabilitation should continue until the patient is considered to have achieved the maximum possible functional improvement. Recovery should be objectively demonstrated with functional assessment scales. | HighI (UEMS-PRMS) |

| After completion of rehabilitation programmes, the subsequent treatment needs of patients with TBI should be assessed periodically to identify and address any change in their functional status. | HighI (UEMS-PRMS) |

| Regular follow-up visits should be scheduled at intervals established in accordance with the patient’s clinical and functional status. | HighI (UEMS-PRMS) |

| Following discharge from any specialised rehabilitation programme (inpatient/outpatient rehabilitation, etc), patients with TBI should be able to schedule consultations with a healthcare professional, at least by telephone, whenever needed, to provide motivation regarding any difficulties they may face and to establish achievable objectives, promoting calmness and helping to solve problems they may experience. | ModeratePriority B (INESSS-ONF) |

| Patients with persistent disability following TBI should be given suitable access to specialised outpatient or community rehabilitation programmes, with a view to achieving progressive improvements that may enable successful reintegration into the community. | LowFundamental C (INESSS-ONF) |

| In patients whose recovery is expected to be slow, rehabilitation planning should consider periodic inpatient admissions. No time limitation should be placed on access to treatment; rather, treatment duration should depend on the patient’s potential to achieve objective functional gains. | LowC (INESSS-ONF) |

| Periodic rehabilitation intervals (e.g, combining periods of readmission or treatment intensification) should be offered to patients with TBI to enable access to the necessary treatment resources as their functional and participation objectives change, or when they meet new challenges or situations that give rise to a new care need. | LowC (INESSS-ONF) |

| After discharge, patients and their families/caregivers should be offered long-term care services (e.g, information, training, etc), with a view to facilitating and guaranteeing the greatest possible level of social participation in the context of each individual’s decisions and promoting adaptation to changes in the patient’s social and family situation resulting from the injury. | LowC (INESSS-ONF) |

| The care model for patients with TBI should follow a bio-psycho-social approach, as TBI should be considered a chronic process whose effects may be lifelong, demanding continuous interventions after completion of inpatient treatment. The ultimate aim of the rehabilitation team is to integrate the patient into a domestic or institutional setting in which they are able to achieve the highest possible level of social participation, quality of life, well-being, and dignity. | LowIV (UEMS-PRMS) |

| Patients with TBI should complete their rehabilitation programmes and be discharged home once the long-term objectives established at the beginning of the rehabilitation programme are achieved, or when no progress in their functional status is observed during an established period of time, or when they are unable to participate in rehabilitation due to worsening of their health or the appearance of a meaningful comorbidity. | LowIII (UEMS-PRMS) |

AHA/ASA: American Heart Association-American Stroke Association; CSBPR: Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Stroke Rehabilitation Practice Guidelines; INESSS-ONF: Institut National d’Excellence en Santé et en Services Sociaux – Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; TBI: traumatic brain injury; UEMS-PRMS: European Union of Medical Specialists – Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine Section.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Coordinator: Enrique Noé Sebastián.

Drafting committee:

Enrique Noé Sebastián, Antonio Gómez Blanco, Montserrat Bernabeu Guitart, and Ignacio Quemada Ubís.

Review or institutional committee: Joan Ferri Campos, Rubén Rodríguez Duarte, Teresa Pérez Nieves, Cristina López Pascua, Sara Laxe García, Carolina Colomer Font, Marcos Ríos Lago, Alan Juárez Belaúnde, Carlos González Alted, and Raúl Pelayo Vergara.