Kinsbourne syndrome, or opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome (OMAS), is a rare aggressive, recurrent, chronic neurological disease of paraneoplastic, parainfectious, or idiopathic origin that also involves the immune system. It negatively affects a critical stage in neurodevelopment as it most frequently appears in paediatric patients aged 6 months to 3 years. The syndrome is characterised by acute or subacute opsoclonus (large, rapid, multi-directional saccades), truncal instability, cerebellar ataxia, and diffuse myoclonus.1–3 In addition to these classic manifestations, the condition may also be associated with irritability, alterations in the sleep-wake cycle, headache, language or visual disorders, dysphagia, vomiting, sialorrhoea, and lethargy.1

As most cases are associated with infections, immunisations, and immunological alterations, there is now extensive evidence that the syndrome is of immune origin, and may be mediated by antibodies associated with dysfunction of T- and B-cells or by antibodies against ACTH, neurofilament proteins, Hu (ANNA-1), Ri (ANNA-2), Yo, Tr, glutamic acid decarboxylase, or amphiphysin. However, the specific antibody responsible for the syndrome is yet to be identified, hence the current lack of treatment models based on the results of clinical trials of systematic treatment protocols. Current treatment for Kinsbourne syndrome includes high-dose corticosteroids, ACTH, intravenous immunoglobulins, cyclophosphamide, plasmapheresis, and even rituximab.1–4

We present the case of a patient who received immunosuppressant therapy with dexamethasone, intravenous human immunoglobulin (IVIg), cyclophosphamide, and verapamil.

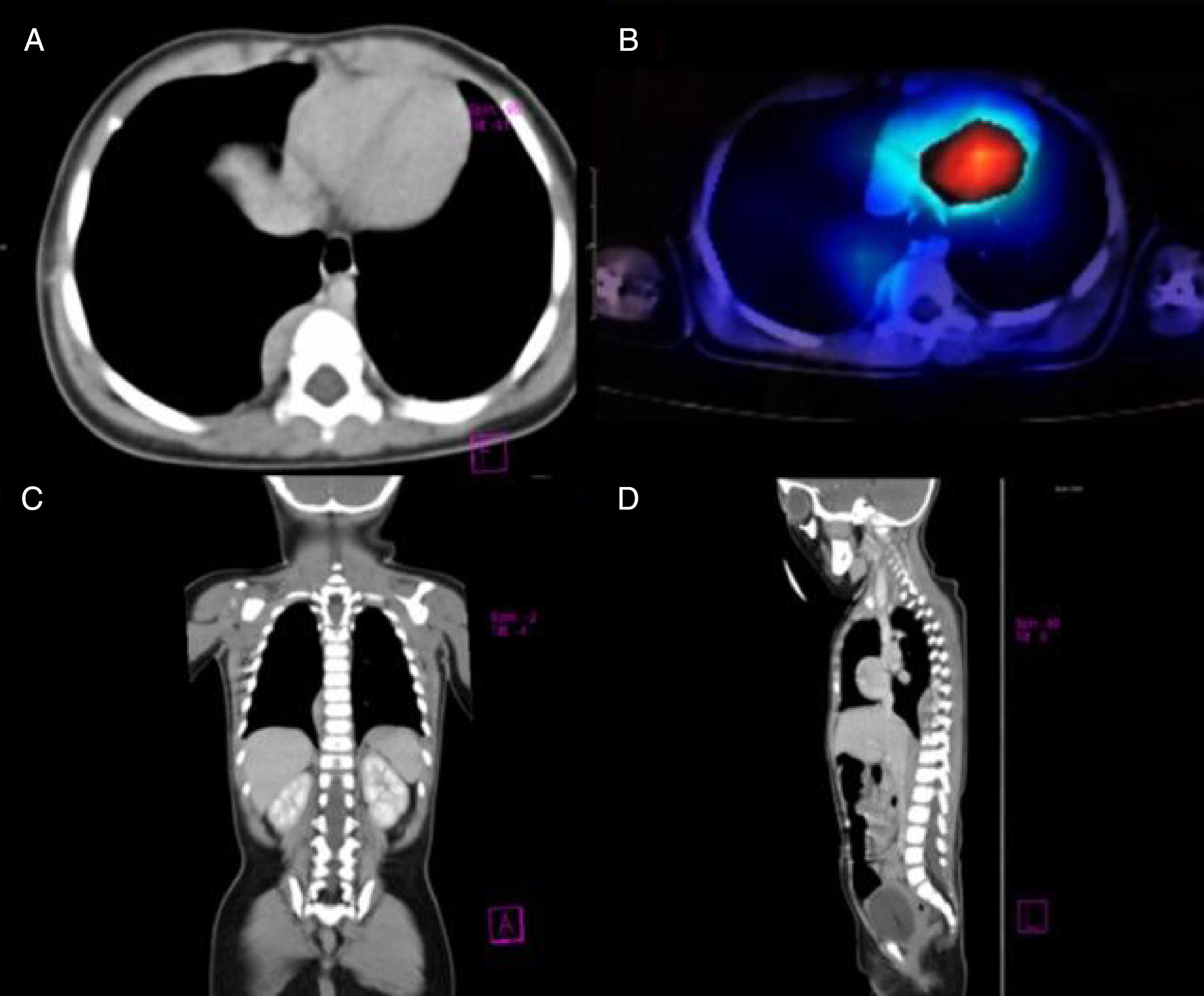

Our patient was a previously healthy 9-month-old infant from the State of Mexico. She had last been vaccinated at 6 months of age. She was admitted due to a 3-week history of fourth cranial nerve palsy, truncal ataxia, and irritability. Ataxia worsened 2 weeks after the onset of the initial symptoms, with the patient becoming unable to sit and progressively developing opsoclonus and sleep-wake cycle alterations. Head CT (1 January 2015) and brain MRI scans (2 January 2015) ruled out space-occupying, inflammatory, and demyelinating lesions. Suspecting postinfectious cerebellitis, we performed a lumbar puncture, with negative results for CSF cytochemical and cytological analyses, Gram staining, CSF cultures, and viral serology tests. As OMAS was suspected, we performed chest CT and 131I-MIBG SPECT scans (30 January 2015), detecting a tumour in the right paravertebral region (Fig. 1). The mass was surgically removed; anatomical pathology findings indicated differentiating neuroblastoma. We confirmed diagnosis of OMAS of paraneoplastic aetiology and started treatment with monthly cycles of dexamethasone (dosed at 20mg/m2 for 3 days), IVIg (2g/kg), and cyclophosphamide (150mg/m2 for 7 days), in addition to verapamil (15mg/8h, until adolescence), for 6 months. After 2 years of treatment, the patient is in complete remission and has no sequelae.

(A) Axial CT image revealing a paravertebral mass at the level of T7, with no signs of invasion of peripheral tissues. (B) 131I-MIBG SPECT image showing an area positive for chromaffin tissue. (C and D) Coronal and parasagittal sections revealing a space-occupying mass in the paravertebral region between T6 and T10.

Multiple treatment protocols for OMAS have been developed. When the syndrome is of paraneoplastic origin, the most frequent treatment approach constitutes surgical resection of the tumour followed by immunomodulatory therapy with ACTH and IVIg.3 Due to the aggressiveness of the syndrome, however, treatment aims to reduce the formation of antibodies potentially involved in the pathophysiology of the condition,3 which leads to symptom resolution. In our case, we decided to administer corticosteroids and immunoglobulin to reduce lymphocytic and phagocytic responses and the production of interleukins.1 Combining these 2 drugs has the advantage of inducing immunomodulation without immunosuppression, leading to complete resolution of neurological symptoms in cases of paraneoplastic OMAS.5 Cyclophosphamide, on the other hand, is an alkylating agent and immunosuppressant used in the treatment of autoimmune disorders.1,6 In recent years, various studies have shown that long-term treatment with P-glycoprotein inhibitors (eg, verapamil) reduces IL-2 production and T-cell proliferation in vitro.7

Although delays in diagnosis or initiation of immunotherapy may result in brain injury, with irreversible neurological impairment, verapamil is reported to protect against cognitive and behavioural disorders in experimental models of Alzheimer disease, as it blocks calcium entry into neurons, inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity, and decreases the production of inflammatory mediators from microglial NADPH oxidase8; this was the reason for our decision to add the drug to our patient's regime.

OMAS in paediatric patients is associated with poor prognosis, with fewer than 20% of cases showing complete recovery. It usually becomes chronic, with relapses varying in number and intensity.6 Our patient, however, remained asymptomatic and displayed no short-term sequelae after 24 months of treatment.

Future studies with longer follow-up periods and larger samples should aim to determine whether the treatment administered to our patient is as effective as or more effective than ACTH for OMAS. In any case, treatment should be multidisciplinary and tailored to each patient's needs.

Please cite this article as: Castañón-González A, Barragán-Pérez E, Hernández-Pliego G, López-Valdés JC. Terapia inmunosupresora en síndrome de opsoclonus-mioclonus ataxia asociado a un neuroblastoma paravertebral. Neurología. 2020;35:54–56.