In clinical practice, assessing patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) is a complex, time-consuming task. Our purpose is to provide a rigorous and objective evaluation of how motor function in PD patients is assessed by neurologists specialising in movement disorders, on the one hand, and by nurses specialising in PD management, on the other.

MethodsWe conducted an observational, cross-sectional, single-centre study of 50 patients with PD (52% men; mean age: 64.7±8.7 years) who were assessed between 5 January 2016 and 20 July 2016. A neurologist and a nurse evaluated motor function in the early morning hours using the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) parts III and IV and Hoehn & Yahr (H&Y) scale. Tests were administered in the same PD periods (in 48 patients during the “off” time and in 2 patients during the “on” time). Inter-rater variability was estimated with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

ResultsForty-nine patients (98%) were classified in the same H&Y stage by both raters. Assessment times were similar for both raters. ICC for UPDRS-IV and UPDRS-III total scores were 0.955 (P<.0001) and 0.954 (P<.0001), respectively. The greatest variability was found for UPDRS-III item 29 (gait; ICC=0.746; P<.0001) and the lowest, for item 30 (postural stability; ICC=0.918; P<.0001).

ConclusionsMotor function assessment of PD patients by a trained nurse is equivalent to that made by an expert neurologist and takes the same time to complete.

En la práctica clínica la evaluación del paciente con enfermedad de Parkinson (EP) es compleja y lleva tiempo. El presente estudio pretende comparar de forma rigurosa y objetiva la evaluación motora del paciente con EP realizada por el neurólogo experto frente a la enfermera especializada de la Unidad de Parkinson.

MétodosEstudio observacional, transversal, monocéntrico en el que se incluyó a 50 pacientes con EP (52% varones, 64,7±8,7 años), que fueron evaluados entre el 05 de enero del 2016 y el 20 de julio del 2016. El neurólogo y la enfermera evaluaron a los pacientes desde el punto de vista motor mediante el uso de las escalas de Hoehn&Yahr (H&Y) modificada, Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale part-iii (UPDRS-III) y part-iv (UPDRS-IV) en el mismo estado motor (48 en OFF y 2 en ON) de forma protocolizada a primera hora de la mañana. Se utilizó el coeficiente de correlación intraclase (CCI) para medir la variabilidad.

ResultadosEl H&Y fue el mismo según ambos evaluadores en 49 de los 50 casos. No hubo grandes diferencias entre el tiempo empleado por ambos evaluadores. El CCI para la UPDRS-IV fue de 0,955 (p<0,0001) y para la UPDRS-III de 0,954 (p<0,0001). La mayor variabilidad en la UPDRS-III fue para el ítem 29 (marcha) con un CCI de 0,746 (p<0,0001) y la menor para el ítem 30 (reflejos posturales) con un CCI de 0,918 (p<0,0001).

ConclusiónLa evaluación motora de los pacientes con EP realizada por una enfermera entrenada es superponible a la del neurólogo experto y empleando un tiempo similar.

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a frequent and complex disorder; good knowledge of the condition is necessary for diagnosis and treatment. Patients with PD present a wide range of symptoms; symptom severity and progression and treatment response are highly variable. Many validated scales are currently used to determine disease severity based on patients’ motor (tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, etc.) and non-motor symptoms (fatigue, pain, sleep disorders, cognitive alterations, depression, anxiety, apathy, impulse control disorder, psychosis, etc.), as well as on their level of independence and quality of life.1,2 In clinical practice, however, physicians have little time to complete these evaluations; a multidisciplinary team should ideally assess patients and make decisions collaboratively.3,4 Nurses specialising in PD management are essential as they play a key role in the integrated care of patients with PD.5,6

While non-motor symptoms are frequently assessed with subjective scales (patients are asked about a specific symptom), motor symptom assessment is objective since it follows a protocolised neurological examination. The examination may be complex, requiring several scales, such as parts III and IV of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS-III: motor examination; UPDRS-IV: motor complications).7 A correctly performed motor examination (“on” and “off” periods, periods with disabling dyskinesias, degree of motor impairment during “on” and “off” periods, axial symptoms, etc.) informs therapeutic decision-making; completion of these tasks by nursing staff would save neurologists time that could be used to other ends (talking with patients, asking about other symptoms, etc.). However, we must be sure that the motor examination is performed correctly if we are to make decisions based on the findings.

This study aims to rigorously and objectively compare the results of a motor examination performed by an expert neurologist to that made by a specialist nurse from our hospital's movement disorders unit.

Material and methodsThis observational, descriptive, cross-sectional, non-interventional study included a series of patients with PD who were enrolled in the COPPADIS-2015 study8; patients were evaluated at the movement disorders unit of Hospital Arquitecto Marcide in Ferrol (Spain) between January and July 2016. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a diagnosis of PD according to the UK Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank criteria9; (2) age between 18 and 75 years; (3) ability to complete the questionnaires; and (4) willingness to participate. We excluded all patients treated with infusion pumps (enteral levodopa and/or apomorphin) or surgery (deep brain stimulation), patients with other causes of parkinsonism, and those meeting the Movement Disorder Society criteria for dementia (MMSE<26/30).10

A neurologist specialising in PD (DSG; evaluating 60 to 90 patients with PD per month at the movement disorders unit since 2009) conducted an initial motor examination, including (in the following order): (1) UPDRS-IV and (2) UPDRS-III,7 followed by the modified Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y)11 scale for determining the stage of disease progression. As soon as possible after the initial examination was completed (to ensure that the patient remained in the same motor state), a specialist nurse from the movement disorders unit (TdDF, employed at the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ferrol since 2013) repeated the motor examination, following the same order. The time taken by the neurologist and the nurse to administer the UPDRS-IV and the UPDRS-III was recorded. Each professional was blinded to the other's results. Data were gathered on epidemiological, clinical, and treatment variables.

The study (titled “Motor Evaluation Comparison Between Neurologist and Specialised Nurse” [MECENAS]) was classified by the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices as a non-post-authorisation study and approved by the clinical research ethics committee of Ferrol and our centre's director. All participants signed informed consent forms. The patients included also participated in the COPPADIS-2015 study, although both studies are compatible in terms of protocol. The MECENAS study was specifically designed to evaluate this inter-rater agreement; the participants met the inclusion criteria established for this end.

DSG performed the statistical analysis using the SPSS statistical software (version 21.0). Quantitative variables are expressed as means±SD and qualitative variables as percentages. The intraclass correlation coefficient12 (ICC) was used to study variability between assessments for each item. We compared overall scores and sum scores for different items to assess variability in different signs or complications: UPDRS-IV.32 to UPDRS-IV.35, dyskinesias; UPDRS-IV.36 to UPDRS-IV.39, motor fluctuations; UPDRS-IV.40 to UPDRS-IV.42, other complications; UPDRS-III.18, language; UPDRS-III.19, hypomimia; UPDRS-III.20 and UPDRS-III.21, tremor; UPDRS-III.22, rigidity; UPDRS-III.23 to UPDRS-III.27, bradykinesia; UPDRS-III.28, posture; UPDRS-III.29, gait; UPDRS-III.30, postural stability; and UPDRS-III.31, body movement. The Cohen kappa coefficient13 was used to analyse agreement in PD classification by the modified H&Y scale and the identification of patients with and without motor fluctuations and/or dyskinesia. Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

ResultsWe recruited 50 patients with PD (52% men; mean age, 64.7±8.7 years) between 5 January and 20 July 2016. By month, the distribution was as follows: 8 in January, 6 in February, 8 in March, 6 in April, 8 in May, 11 in June, and 3 in July. Forty-eight patients were evaluated during “off” periods (between 8.00 and 9.00 am in all cases; they had taken no medications in the previous 12h) and 2 during “on” periods (in the morning, during the patients’ best “on” period after receiving the medication). Mean time between the beginning of each examination was 30.8±14.3minutes.

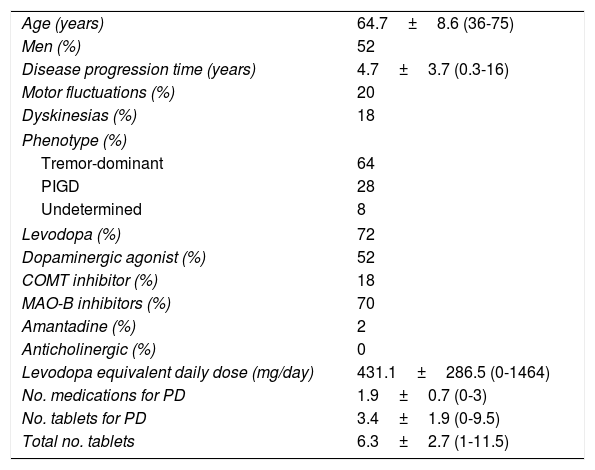

Mean disease progression time was slightly shorter than 5 years; approximately one in every 5 patients showed motor complications (20% motor fluctuations, 18% dyskinesias). The tremor-dominant phenotype14 was the most common in our sample. Levodopa was the most frequently administered medication (72%), followed by monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors (70%). Table 1 lists some characteristics associated with the disease and different medications.

Characteristics of the sample (n=50).

| Age (years) | 64.7±8.6 (36-75) |

| Men (%) | 52 |

| Disease progression time (years) | 4.7±3.7 (0.3-16) |

| Motor fluctuations (%) | 20 |

| Dyskinesias (%) | 18 |

| Phenotype (%) | |

| Tremor-dominant | 64 |

| PIGD | 28 |

| Undetermined | 8 |

| Levodopa (%) | 72 |

| Dopaminergic agonist (%) | 52 |

| COMT inhibitor (%) | 18 |

| MAO-B inhibitors (%) | 70 |

| Amantadine (%) | 2 |

| Anticholinergic (%) | 0 |

| Levodopa equivalent daily dose (mg/day) | 431.1±286.5 (0-1464) |

| No. medications for PD | 1.9±0.7 (0-3) |

| No. tablets for PD | 3.4±1.9 (0-9.5) |

| Total no. tablets | 6.3±2.7 (1-11.5) |

COMT: catechol-O-methyltransferase; MAO-B: monoamine oxidase B; PD: Parkinson's disease; PIGD: postural instability and gait disorder; SD: standard deviation. Data are expressed as percentages and/or means±SD (range).

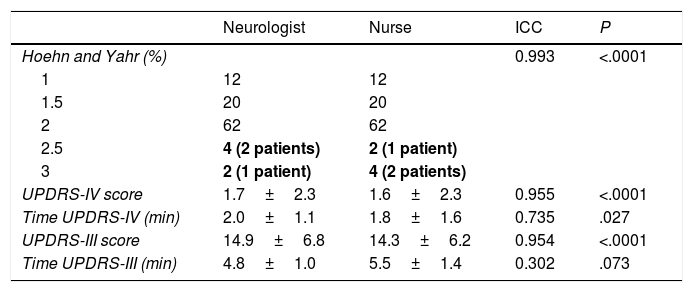

Forty-nine patients (98%) were classified into the same H&Y stage by the neurologist and the nurse, with a Cohen kappa coefficient of 0.964 (P<.0001). The remaining patient was classified as H&Y stage 2.5 by the neurologist and stage 3 by the nurse (Table 2). The neurologist and the nurse gave similar mean scores for UPDRS-IV (1.7±2.3 vs 1.6±2.3) and UPDRS-III (14.9±6.8 vs 14.3±6.2) (Table 2). Variability in H&Y stages and UPDRS-IV and UPDRS-III scores was extremely low; the ICC was over 0.950 in all cases (P<.0001). The UPDRS-IV took the neurologist significantly longer to administer (2.0±1.1 vs 1.8±1.6min; P=.027); no significant differences in administration time were observed for the UPDRS-III (4.8±1.0 vs 5.5±1.4min; P=.073) (Table 2).

Agreement between neurologist and nurse assessment for Hoehn and Yahr stage and total UPDRS-III and UPDRS-IV scores, and assessment times.

| Neurologist | Nurse | ICC | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoehn and Yahr (%) | 0.993 | <.0001 | ||

| 1 | 12 | 12 | ||

| 1.5 | 20 | 20 | ||

| 2 | 62 | 62 | ||

| 2.5 | 4 (2 patients) | 2 (1 patient) | ||

| 3 | 2 (1 patient) | 4 (2 patients) | ||

| UPDRS-IV score | 1.7±2.3 | 1.6±2.3 | 0.955 | <.0001 |

| Time UPDRS-IV (min) | 2.0±1.1 | 1.8±1.6 | 0.735 | .027 |

| UPDRS-III score | 14.9±6.8 | 14.3±6.2 | 0.954 | <.0001 |

| Time UPDRS-III (min) | 4.8±1.0 | 5.5±1.4 | 0.302 | .073 |

ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; UPDRS: Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale.

Lack of agreement between nurse and neurologist is indicated in bold.

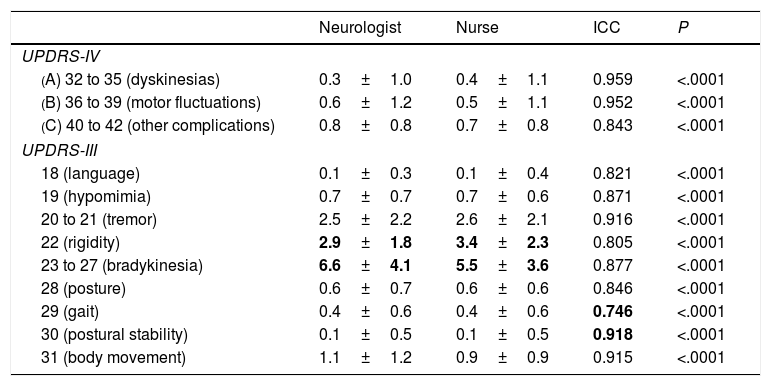

The analysis of each item of the UPDRS-IV and UPDRS-III for different signs or complications showed low inter-rater variability, with an ICC above 0.740 in all cases (P<.0001). In the UPDRS-IV, the greatest variability was observed in items 40 to 42, which evaluate complications (nausea, sleep alterations, and orthostasis) other than motor fluctuations and dyskinesias (ICC>0.950 in both cases; P<.0001); the ICC for “other complications” was 0.843 (P<.0001) (Table 3). We observed little variability in the classification of patients as having motor fluctuations and/or dyskinesias (Cohen kappa coefficients of 0.874 and 0.703, respectively; P<.0001). The greatest differences in mean UPDRS-III scores between the neurologist's and the nurse's examinations were observed in rigidity and bradykinesia, with the nurse scoring patients higher for rigidity and the neurologist for bradykinesia. The greatest variability was observed in gait (UPDRS-III.29, ICC of 0.746; P<.0001) and the lowest in postural stability (UPDRS-III.30, ICC of 0.918; P<.0001) (Table 3).

Variability between neurologist and nurse UPDRS-III and UPDRS-IV scores, broken down by signs and/or symptoms.

| Neurologist | Nurse | ICC | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPDRS-IV | ||||

| (A) 32 to 35 (dyskinesias) | 0.3±1.0 | 0.4±1.1 | 0.959 | <.0001 |

| (B) 36 to 39 (motor fluctuations) | 0.6±1.2 | 0.5±1.1 | 0.952 | <.0001 |

| (C) 40 to 42 (other complications) | 0.8±0.8 | 0.7±0.8 | 0.843 | <.0001 |

| UPDRS-III | ||||

| 18 (language) | 0.1±0.3 | 0.1±0.4 | 0.821 | <.0001 |

| 19 (hypomimia) | 0.7±0.7 | 0.7±0.6 | 0.871 | <.0001 |

| 20 to 21 (tremor) | 2.5±2.2 | 2.6±2.1 | 0.916 | <.0001 |

| 22 (rigidity) | 2.9±1.8 | 3.4±2.3 | 0.805 | <.0001 |

| 23 to 27 (bradykinesia) | 6.6±4.1 | 5.5±3.6 | 0.877 | <.0001 |

| 28 (posture) | 0.6±0.7 | 0.6±0.6 | 0.846 | <.0001 |

| 29 (gait) | 0.4±0.6 | 0.4±0.6 | 0.746 | <.0001 |

| 30 (postural stability) | 0.1±0.5 | 0.1±0.5 | 0.918 | <.0001 |

| 31 (body movement) | 1.1±1.2 | 0.9±0.9 | 0.915 | <.0001 |

ICC: Intraclass correlation coefficient; UPDRS: Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale.

The data in bold show the greatest differences between mean scores (neurologist vs nurse) and the highest and lowest ICCs, indicating the items with the highest and the lowest level of agreement.

Our results show that the motor examination performed by a nurse specialising in PD management is similar to that made by a neurologist specialising in movement disorders. Differences were minimal; the results reported by the 2 healthcare professionals in terms of H&Y stage and UPDRS-IV and UPDRS-III scores, and the time taken to complete the assessment, were similar. These findings support the possibility of nurses being responsible for complementary tasks15,16 to support neurologists, affording them more time for patient care. In other words, the motor examination may be performed by nursing staff both in routine clinical practice and in research projects.

Nurses specialising in PD management have played an active role in some countries, such as the United Kingdom, since the 1990s17,18 and are becoming increasingly important in other countries.16 In addition to the functions inherent to their position, specialist nurses may also perform such other tasks as informing and educating patients and carers, ensuring proper treatment adherence, solving any doubts or problems that may arise, or managing devices in patients receiving second-line treatments (deep brain stimulation and infusion pumps).19–22 Specialist nurses may help reduce waiting times, prevent unnecessary hospital admissions, or reduce post-surgery times; some centres are successfully implementing programmes for teleconsultation with nursing staff as the initial contact between patients with PD and healthcare professionals.23,24 Some randomised trials have shown similar cost-effectiveness for initial consultations with nurses and with general practitioners.25 In Spain, a recently developed integrated care plan for Parkinson's disease specifically addresses the crucial role of nurses in the management of patients with PD.26 Healthcare centres have fewer nurses specialising in PD than recommended, despite evidence that they reduce long-term healthcare costs and overburdening of neurologists.23 More initiatives should be developed to grant patients access to this type of care.27–29

Specialist nurses can assess not only non-motor symptoms, based on patients’ subjective impressions of specific symptoms,8,30,31 but also motor symptoms, following an examination protocol. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies.32–34 Bennet et al.32 observed excellent agreement between the assessment results from 3 nurses evaluating 75 patients with PD using the UPDRS-III (ICC>0.97 in all cases), and good to excellent agreement between them and an expert neurologist (ICC>0.90 for total scores, ranging between 0.76 and 0.95 depending on the domain). Post et al.33 studied inter-rater variability in UPDRS-III scores from 50 patients with PD assessed by 2 nurses and 2 neurology residents on the one hand, and a neurologist specialising in movement disorders on the other, reporting ICCs of 0.91 (nurse 1) and 0.90 (nurse 2), similar to those of the neurology residents (0.90 and 0.86). Palmer et al.34 studied 46 patients with Alzheimer disease and found moderate agreement between the results of motor examinations (UPDRS-III) performed by the nurse and the neurologist, with an ICC of 0.65 and a Cohen kappa coefficient of 0.53 (normal vs abnormal UPDRS-III results). This suggests that it may be difficult to determine whether results are normal or abnormal (e.g., bradykinesia) in patients with mild or no known PD.34,35 In our study, agreement was lowest for gait (UPDRS-III.29) and highest for postural stability (UPDRS-III.30). Agreement was also high for rigidity and bradykinesia (ICC>0.80 in both cases); however, different mean scores were recorded, with the nurse tending to overrate rigidity and the neurologist tending to overrate bradykinesia. Other studies also report a high level of agreement in postural stability,33 a fundamental factor for determining the H&Y stage. In general terms, these results reflect the variability that may be observed between neurologists specialising in movement disorders.36

In addition to evaluating inter-rater agreement for UPDRS-III scores, this study is the first to evaluate inter-rater agreement for UPDRS-IV scores, assessing motor complications, and assessment times. We found excellent agreement between the neurologist and the nurse for detecting motor fluctuations and/or dyskinesias. Broadly speaking, the UPDRS-III takes around 5minutes to administer, and the UPDRS-IV takes approximately 2minutes. Although the nurse took longer to complete the UPDRS-III, this difference was not significant, and time taken varied greatly depending on the patient (ICC of 0.302). The shorter time it took the nurse to administer the UPDRS-IV (P=.027) may be explained by the fact that the neurologist had already evaluated the patient, who was therefore able to answer the questions faster and more precisely. These findings suggest that specialist nurses may not only determine patients’ level of motor impairment but also identify motor complications; this, combined with patient diaries, may provide the neurologist with crucial information for therapeutic decision-making (duration and timing of “on” and “off” periods and disabling dyskinesias, level of impairment during “on” and “off” periods, administration times).

Our study has several limitations. We did not evaluate intra-rater reliability. Although the time elapsed between assessments was shorter than 30minutes, the examinations were performed in different rooms (10m apart, but with a different layout). The neurologist (DSG) has expertise in administering the UPDRS (participating in international phase-IV trials); we cannot therefore rule out bias in the nurse's assessment due to her familiarity with the scale through experience working with him. Finally, our results do not allow us to confirm the reliability of nurse assessments for clinical trials or longitudinal studies. In any case, the study was designed with a specific aim and has accomplished its purpose, providing novel data on the agreement between UPDRS-IV scores (motor complications) established by a nurse and a neurologist.

In conclusion, specialist nurses can assess motor function in patients with PD, with similar results to those of expert neurologists in terms of reliability and time taken to complete the examination. This should be taken into account when planning patient management at movement disorders units, reducing neurologists’ workloads and allowing them to devote more time to patient care and assessing other aspects of the disease.

Author contributionsTeresa de Deus Fonticoba: patient assessment, critical review of the manuscript.

Diego Santos García, MD, PhD: patient assessment; conception, organisation, and execution of the project; manuscript drafting.

Mercedes Macías Arribí: patient assessment, critical review of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The study has received no funding of any kind.

Please cite this article as: de Deus Fonticoba T, Santos García D, Macías Arribí M. Variabilidad en la exploración motora de la enfermedad de Parkinson entre el neurólogo experto en trastornos del movimiento y la enfermera especializada. Neurología. 2019;34:520–526.