Non-aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is a rare entity that accounts for approximately 15% of all cases of spontaneous SAH.1 Perimesencephalic SAH is a type of non-aneurysmal SAH characterised by location in the basal cisterns, with excellent prognosis.2,3 The source of bleeding in perimesencephalic SAH is unknown, although the most widely accepted hypothesis suggests that aetiology is venous, including drainage abnormalities or stenosis of the vein of Galen.1,2 A recent study of a series of patients with perimesencephalic SAH reports 2 cases of dural arteriovenous fistulas (DAVF).4 However, the causal relationship between the 2 entities is still much debated; furthermore, very few studies have been published on the topic, which hinders therapeutic decision-making in patients with perimesencephalic SAH and an underlying DAVF.

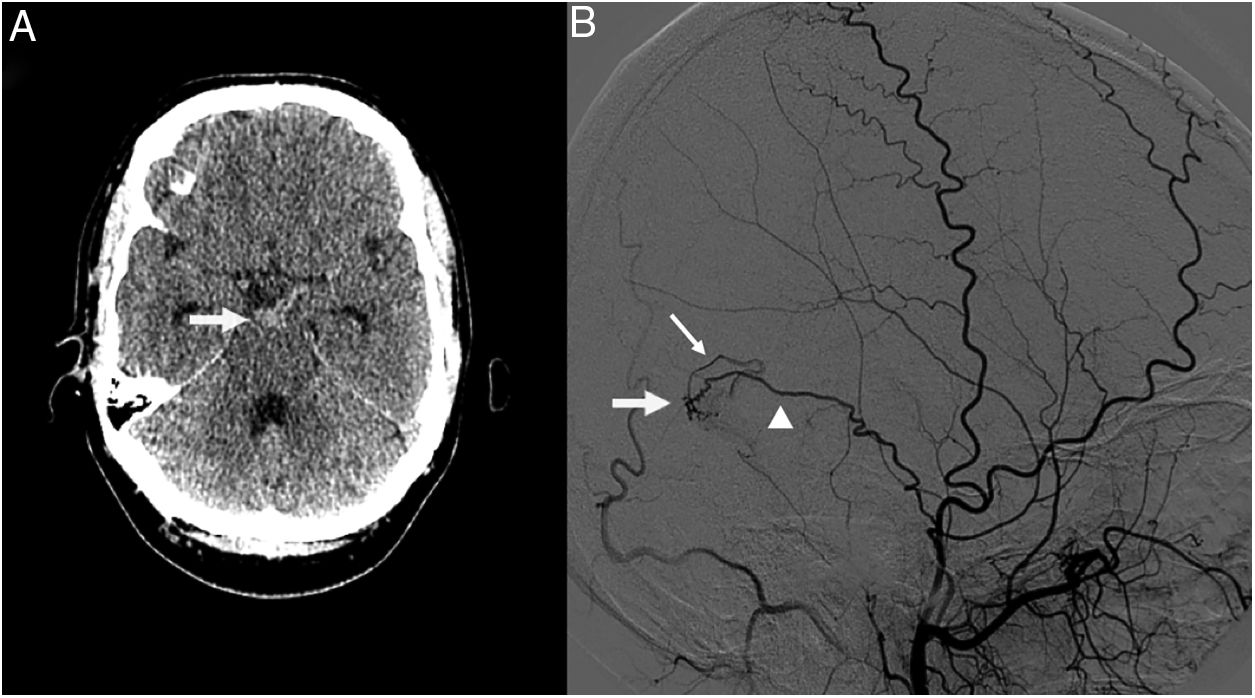

We present the case of a 39-year-old man who visited our hospital due to sudden onset of severe headache and neck pain. The physical examination revealed severe nuchal rigidity with no clear focal neurological signs. A head CT scan identified an SAH in the interpeduncular cistern (Fig. 1A), and an emergency CT angiography of the supra-aortic and cerebral arteries revealed no signs of underlying neurovascular disease. A digital subtraction angiography of the cerebral vessels performed 24hours after admission (Fig. 1B) detected a DAVF in the right transverse sinus, fed by a temporal branch of the ipsilateral middle meningeal artery, with retrograde drainage into a cortical vein (type III according to the Cognard classification5). The fistula was successfully treated with cyanoacrylate embolisation. The patient progressed favourably, and was discharged without symptoms 15 days after the initial event.

A) Head CT scan showing a subarachnoid haemorrhage in the interpeduncular cistern (arrow). B) Digital subtraction angiography of the cerebral vessels revealed a dural arteriovenous fistula in the right transverse sinus (arrow), fed by a temporal branch of the ipsilateral middle meningeal artery (arrowhead), with retrograde drainage into a cortical vein (thin arrow).

DAVFs are abnormal connections between meningeal arteries and small venules located in the dura mater, and cause approximately 10% of all intracranial shunts. They are usually classified according to the pattern of venous drainage (Cognard and Borden classifications), and are considered eligible for treatment if they present bleeding or retrograde venous flow (particularly through dilated cortical veins), since they are associated with a high risk of spontaneous haemorrhage (malignant dural fistulas).5,6 Malignant DAVFs have classically been associated with cerebral haemorrhage due to rupture of the venous structures of the fistula. On occasion, they can have a subdural component, and many studies report a clear association between DAVFs and diffuse (non-perimesencephalic) SAHs.7,8

However, the association between DAVFs and perimesencephalic SAHs, as well as small, sulcal SAHs is not clearly established due to limited evidence, uncertainty about the pathophysiological mechanism, and discrepancies between the location of the fistula and the bleeding site. Among the few similar cases published, Heit et al.9 detected a DAVF (location not specified) in a patient with sulcal SAH, Ohshima et al.4 found a DAVF of the right transverse sinus in a patient with sulcal SAH in the contralateral hemisphere, and some cases of perimesencephalic SAH have been observed in patients with spinal DAVFs.10,11 The authors of these studies have reservations about the causal association between both entities, but argue that we cannot ignore the fact that DAVFs are much more frequent among patients with perimesencephalic SAH than in the general population. For example, Ohshima et al.4 found 2 DAVFs in a sample of 20 patients with perimesencephalic SAH; this represents an incidence of 10%, a much higher rate than the estimated incidence of DAVFs in the Japanese general population (0.29 cases per 100000 person-years) or in the population of Minnesota (0.15 cases per 100000 person-years).7 To further complicate the situation, some of these DAVFs were not detected in the baseline angiography study, but rather in follow-up angiography studies; this may indicate, as other authors have suggested, that “the mechanisms of DAVF are also unclear and may be related to preexisting venous abnormalities such as occult venous thrombosis.”4 It is therefore unclear whether management of DAVFs in patients with perimesencephalic SAH should be based on the assumption that the fistula is the cause of the bleeding.

In our centre, we detected a DAVF in the baseline angiography study of one of 96 cases of perimesencephalic SAH recorded over the last 5 years (1.04%). That patient, whose case we describe here, presented a DAVF in the transverse sinus with drainage into a cortical vein, detected following a perimesencephalic SAH. Despite the evident neuroanatomical uncertainties about the association between fistula location and bleeding, and in view of the controversy mentioned previously, we opted to perform endovascular closure of the fistula, although we were aware that conservative treatment was also an option. This isolated case may be interesting in view of the scarce literature on the topic. Given the low incidence of this condition, publication of isolated cases may in the future help to determine the relationship between both entities and to establish the best treatment option.

Please cite this article as: Páez-Granda D, Parrilla G, Espinosa de Rueda M, Berná-Serna JD. Fístula arteriovenosa dural intracraneal y hemorragia subaracnoidea perimesencefálica. A propósito de un caso. Neurología. 2020;35:514–515.