Epilepsy is the most common neurological disease in childhood; depending on the definition of drug-resistant epilepsy, incidence varies from 10% to 23% in the paediatric population. The objective of this study was to account for the decrease in the frequency and/or monthly duration of epileptic seizures in paediatric patients with drug-resistant epilepsy treated with antiepileptic drugs, before and after adding intravenous immunoglobulin G (iIV IgG).

MethodsThis is an analytic, observational, retrospective case–control study. We studied paediatric patients with drug-resistant epilepsy who were treated with IV IgG at the Centro Médico Nacional 20 de Noviembre, in Mexico City, from 2003 to 2013.

ResultsOne hundred and sixty seven patients (19.5%) had drug-resistant epilepsy and 44 (5.1%) started adjuvant treatment with IV IgG. The mean age of patients at the beginning of treatment was 6.12 years(5.14); aetiology was structural acquired in 28 patients (73.6%), genetic in 5 (13.1%), immune in 1 (2.6%), and unknown in 4 (10.5%). At 2 months from starting IV IgG, seizure duration had reduced to 66.66%; the frequency of seizures was reduced by 64% at 4 months after starting treatment (P<.001).

ConclusionsAccording to the results of this study, intravenous immunoglobulin may be an effective therapy for reducing the frequency and duration of seizures in paediatric patients with drug-resistant epilepsy.

La epilepsia es la enfermedad neurológica más común en la infancia; dependiendo de la definición de epilepsia farmacorresistente la incidencia varía del 10 a 23% en la población pediátrica. El objetivo de este estudio fue contabilizar la disminución en la frecuencia y/o duración mensual de crisis epilépticas en pacientes pediátricos con epilepsia farmacorresistente tratados con antiepilépticos, antes y después de la adición de inmunoglobulina G intravenosa (IgG iv).

MétodosEstudio analítico, observacional retrospectivo de casos-controles. Se estudiaron pacientes pediátricos con epilepsia farmacorresistente atendidos en el Centro Médico Nacional 20 de Noviembre de la Ciudad de México durante el período 2003-2013 y que recibieron tratamiento con IgG iv.

ResultadosCiento sesenta y siete pacientes (19,5%) presentaron epilepsia farmacorresistente y 44 (5,1%) iniciaron tratamiento adyuvante con IgG iv. La edad media de los pacientes al inicio del tratamiento fue de 6,12 años (5,14); 28 (73,6%) tuvieron una etiología estructural adquirida, 5 (13,1%) genética, uno (2,6%) inmune y 4 (10,5%) desconocida. A los 2 meses de la aplicación de inmunoglobulina la duración de las crisis se redujo al 66,66% y la frecuencia de las crisis alcanzó una reducción del 64% a los 4 meses de iniciado el tratamiento (p<0,001).

ConclusionesLa IgG iv puede ser una terapia eficaz para la disminución en la frecuencia y duración de las convulsiones en pacientes pediátricos con epilepsia farmacorresistente, como lo demuestran los resultados de este estudio.

Epilepsy is a common neurological disease in childhood, affecting 0.5% to 1% of the paediatric population. Approximately one in every 150 children is diagnosed with epilepsy in the first 10 years of life.1,2 Around 3.5 million new cases of epilepsy are reported annually; 40% of these patients are younger than 18 years, and over 80% live in developing countries. Unfortunately, 6% to 14% of these children will develop drug-resistant epilepsy.3 The incidence of drug-resistant epilepsy in the paediatric population ranges from 10% to 23%, depending on the definition used in each study.4

Drug-resistant epilepsy is defined by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) as failure of 2 antiepileptic drug (AED) schedules to achieve sustained seizure freedom.5 Risk factors for drug-resistant childhood epilepsy include age below one year, symptomatic epilepsy, neurodevelopmental delay, and pathological neuroimaging findings.6,7 Intravenous immunoglobulin (IV IgG) has been reported to be an effective adjuvant treatment for drug-resistant epilepsy in childhood. Persistent seizures and poor seizure control are known to have a negative psychosocial, behavioural, cognitive, and economic impact and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.8

MethodsStudy designThis analytical, observational, retrospective case–control study included a sample drawn by convenience sampling, with each patient serving as his or her own control. The study was approved by the research ethics committee at Hospital Centro Médico Nacional “20 de Noviembre,” in Mexico City.

Patients and definitionsWe reviewed the electronic medical records of all patients aged under 18 years and attended at our centre's paediatric neurology department between January 2003 and December 2013. Patients with drug-resistant epilepsy and receiving immunoglobulin were considered for analysis, regardless of the type of epilepsy.

We identified a total of 856 patients with epilepsy, 167 of whom (19.5%) developed drug-resistant epilepsy. Ours is a highly specialised reference centre; most of our patients live in other Mexican states. According to the medical records, 44 of the 167 patients with drug-resistant epilepsy (5.1% of the total sample) started treatment with IV IgG. Six patients received a single dose of IV IgG but did not return for subsequent treatment; these patients were excluded from our analysis.

We used the previously mentioned ILAE definition of drug-resistant epilepsy, as well as the definition of drug-resistant childhood epilepsy, which also considers the presence of at least one seizure per month for 18 months.9–11 All patients met the definition for drug-resistant epilepsy; decreases of ≥50% in monthly seizure frequency and/or duration compared to baseline were regarded as significant.

Each patient served as his or her own control; we compared seizure frequency and duration at baseline (3 months before onset of IV IgG treatment; control data) and at 2, 4, and 6 months of treatment.

AssessmentsPatients received 6 cycles of IV IgG dosed at 0.4g/kg for 5 consecutive days, with a 3-week interval between cycles. Human IgG was used for treatment; each flask contained 6g immunoglobulin in 0.9% saline solution. According to our medical records, the neurological examination, AED dose adjustment, and IV IgG dose calculation were conducted by members of the paediatric neurology department.

Statistical analysisData were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and exported to R (version 3.0.1) for statistical analysis. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies, and continuous variables as medians (range). The Friedman test was used to analyse continuous variables, as paired data (data gathered before and after treatment) were not normally distributed.

Data are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Two-tailed P values <.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

ResultsBetween 2003 and 2013, our paediatric neurology department attended 856 patients with epilepsy, of whom 167 (19.5%) developed drug-resistant epilepsy and 44 (5.1%) were treated with IV IgG. Treatment was withdrawn in 6 patients, who were therefore excluded; the final sample included 38 patients (26 boys [68.4%] and 12 girls [31.6%]).

Mean age of epilepsy onset was 2 years and mean age (SD) at onset of IV IgG treatment was 6.12 (5.14) years.

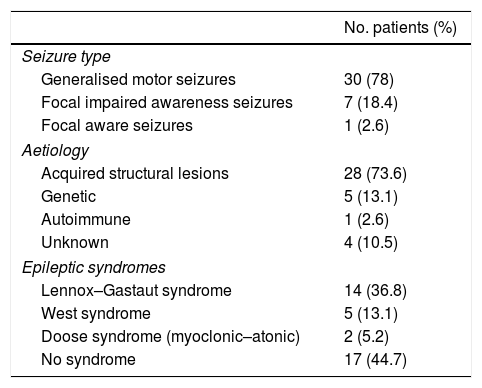

Epilepsy was due to acquired structural causes in 28 patients (73.6%); aetiology was genetic in 5 (13.1%), autoimmune in one (2.6%), and unknown in 4 (10.5%). The most frequent epileptic syndromes, in descending order, were Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, West syndrome, and Doose syndrome (Table 1).

Frequency of epileptic seizures and epilepsy, by type.

| No. patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Seizure type | |

| Generalised motor seizures | 30 (78) |

| Focal impaired awareness seizures | 7 (18.4) |

| Focal aware seizures | 1 (2.6) |

| Aetiology | |

| Acquired structural lesions | 28 (73.6) |

| Genetic | 5 (13.1) |

| Autoimmune | 1 (2.6) |

| Unknown | 4 (10.5) |

| Epileptic syndromes | |

| Lennox–Gastaut syndrome | 14 (36.8) |

| West syndrome | 5 (13.1) |

| Doose syndrome (myoclonic–atonic) | 2 (5.2) |

| No syndrome | 17 (44.7) |

The most frequent type of epileptic seizures were generalised motor seizures (30 patients; 78%), followed by focal impaired awareness seizures (7; 18.4%), and focal aware seizures (1; 2.6%).

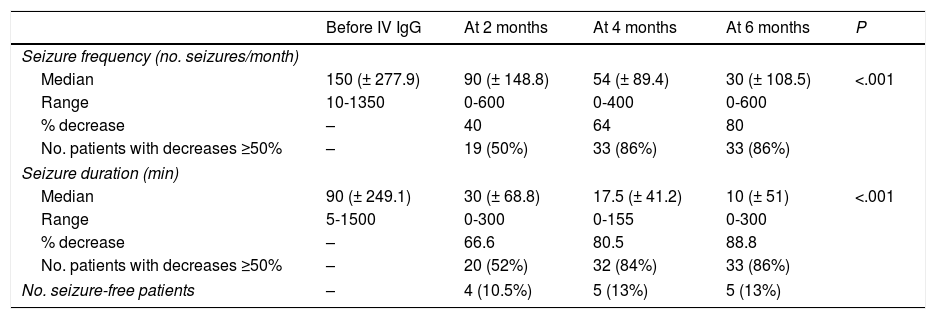

Seizure duration decreased by 66.66% at 2 months after onset of treatment with IV IgG, with seizure frequency decreasing by 64% at 4 months (P<.001) (Table 2).

Changes in seizure frequency and duration over time.

| Before IV IgG | At 2 months | At 4 months | At 6 months | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seizure frequency (no. seizures/month) | |||||

| Median | 150 (± 277.9) | 90 (± 148.8) | 54 (± 89.4) | 30 (± 108.5) | <.001 |

| Range | 10-1350 | 0-600 | 0-400 | 0-600 | |

| % decrease | – | 40 | 64 | 80 | |

| No. patients with decreases ≥50% | – | 19 (50%) | 33 (86%) | 33 (86%) | |

| Seizure duration (min) | |||||

| Median | 90 (± 249.1) | 30 (± 68.8) | 17.5 (± 41.2) | 10 (± 51) | <.001 |

| Range | 5-1500 | 0-300 | 0-155 | 0-300 | |

| % decrease | – | 66.6 | 80.5 | 88.8 | |

| No. patients with decreases ≥50% | – | 20 (52%) | 32 (84%) | 33 (86%) | |

| No. seizure-free patients | – | 4 (10.5%) | 5 (13%) | 5 (13%) | |

The number of AEDs used before and after onset of treatment with IgG was 2.65 and 2.84, respectively; this difference was not statistically significant (P=.655).

Five patients underwent surgery (13.1%): 3 underwent nerve stimulator implantation (the device was implanted one and 2 years before and one year after IV IgG treatment onset, respectively), whereas the remaining 2 patients underwent corpus callosotomy (6 years before and one year after treatment onset, respectively).

DiscussionIn our study, 19.5% of patients developed drug-resistant epilepsy and 5.1% received IV IgG. Similar rates are reported by Yilmaz et al.3 and in other studies that use different definitions of drug-resistant epilepsy (10% to 23%).4

According to Geerts et al.,12 the aetiology of drug-resistant epilepsy is symptomatic in 22.6% of patients; in our study, drug-resistant epilepsy was most frequently acquired due to a structural lesion (73.6%). Although the study by Geerts et al.12 uses an older classification of epilepsy aetiology, there is a connection between symptomatic causes and acquired structural causes. In our study, most cases of acquired drug-resistant epilepsy were due to perinatal hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury.

In terms of patients’ response to adjuvant treatment with IV IgG, seizure frequency decreased by 40% at 2 months in half of the patients and by ≥50% at 4 months in 86% of patients; decreases persisted at 6 months of follow-up (P<.01). The literature reports variable results. Granata13 (N=15; 2003) reports a reduction in seizure frequency in 86% of patients, Billiau et al.14 in 31% (N=13; 2007), Mikati et al.15 in 43% (N=37; 2009), Geva-Dayan et al.16 in 15% (N=64; 2012), and Bello-Espinosa et al.11 in 81% (N=27; 2015).

The most recent reviews in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews include only one randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial of adult and paediatric patients treated with immunoglobulin, which reported treatment response in 52.5% of patients (vs 27.78% of controls; P=.095).17,18

This reflects the great variability in the rates of response to immunoglobulin treatment in these patients,9 regardless of epilepsy aetiology,19 including immunological alterations. Our results are consistent with those published previously.

No significant decrease was detected in the number of AEDs administered after onset of IV IgG treatment, which supports the use of immunoglobulin as an adjuvant treatment.

Our study has a number of limitations, including those inherent to its retrospective, observational design; the fact that each participant served as his or her own control; the lack of randomisation; the fact that data were gathered from medical records; the lack of control over certain variables; and the lack of a placebo-controlled group. Despite their lower level of evidence, observational studies provide valid information about diseases where clinical trials are not easy to perform. This is the first study to evaluate treatment response in terms of seizure duration in addition to seizure frequency; previous studies analyse seizure frequency exclusively.

Our results show a positive correlation between seizure frequency and duration; however, decreases of ≥ 50% were first seen in seizure duration and subsequently in seizure frequency (at 2 months, 52% of patients already displayed a 66% decrease in seizure duration; P<.001).

This reflects the impact of immunoglobulin as adjuvant treatment for patients with drug-resistant epilepsy and the importance of analysing both of the parameters studied before concluding that treatment has failed.

ConclusionsOur results support the effectiveness of IV IgG adjuvant treatment for drug-resistant childhood epilepsy, regardless of the aetiology of the disease.

Our study contributes important information on this little-explored topic and underscores the importance of conducting clinical trials in this area.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: González-Castillo Z, Solórzano Gómez E, Torres-Gómez A, Venta Sobero JA, Gutiérrez Moctezuma J. Inmunoglobulina G intravenosa como tratamiento adyuvante en epilepsia infantil farmacorresistente. Neurología. 2020;35:395–399.