The contrast sensitivity test determines the quality of visual function in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). The purpose of this study is to analyse changes in visual function in patients with relapsing-remitting MS with and without a history of optic neuritis (ON).

MethodsWe conducted a longitudinal study including 61 patients classified into 3 groups as follows: (a) disease-free patients (control group); (b) patients with MS and no history of ON; and (c) patients with MS and a history of unilateral ON. All patients underwent baseline and 6-year follow-up ophthalmologic examinations, which included visual acuity and monocular and binocular Pelli-Robson contrast sensitivity tests.

ResultsMonocular contrast sensitivity was significantly lower in MS patients with and without a history of ON than in controls both at baseline (P=.00 and P=.01, respectively) and at 6 years (P=.01 and P=.02). Patients with MS and no history of ON remained stable throughout follow-up whereas those with a history of ON displayed a significant loss of contrast sensitivity (P=.01). Visual acuity and binocular contrast sensitivity at baseline and at 6 years was significantly lower in the group of patients with a history of ON than in the control group (P=.003 and P=.002 vs P=.006 and P=.005) and the group with no history of ON (P=.04 and P=.038 vs P=.008 and P=.01). However, no significant differences were found in follow-up results (P=.1 and P=.5).

ConclusionsMonocular Pelli-Robson contrast sensitivity test may be used to detect changes in visual function in patients with ON.

El examen de la sensibilidad al contraste permite determinar la calidad de la función visual en pacientes con esclerosis múltiple (EM). El objetivo de este estudio es analizar las modificaciones evolutivas de la función visual en pacientes con EM remitente-recurrente.

MétodosEstudio longitudinal de 61 pacientes clasificados en 3 grupos: a) pacientes libres de enfermedad (grupo control); b) pacientes con EM y sin antecedentes de neuritis óptica (NO), y c) pacientes con EM y antecedentes de NO unilateral. A todos los pacientes se les realizó una exploración oftalmológica que incluía agudeza visual y test de sensibilidad al contraste tipo Pelli-Robson mono y binocularmente, tanto al inicio como a los 6 años de seguimiento.

ResultadosLa sensibilidad al contraste monocular en pacientes con EM con y sin antecedentes de NO fue significativamente inferior al grupo control tanto al inicio (p=0,00 y p=0,01) como a los 6 años (p=0,01 y p=0,02), manteniéndose estable a lo largo del seguimiento excepto en el grupo de pacientes con NO en el cual existe una pérdida significativa de sensibilidad al contraste (p=0,01). La agudeza visual y la sensibilidad al contraste binocular al inicio y a los 6 años de seguimiento fueron significativamente inferiores en el grupo de pacientes con antecedentes de NO que en el grupo control (p=0,003 y p=0,002; p=0,006 y p=0,005) y con EM sin NO (p=0,04 y p=0,038; p=0,008 y p=0,01); sin embargo, no encontramos diferencias significativas en el seguimiento (p=0,1 y p=0,5).

ConclusionesEl test de Pelli-Robson monocular podría servir como marcador evolutivo del deterioro de la función visual en ojos con NO.

Visual impairment is one of the most significant causes of disability in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS),1 with 80% of patients developing some degree of visual impairment during the progression of the disease.2 Given the prevalence of this symptom and the negative impact of vision loss on quality of life, visual function is one of the parameters analysed in the majority of clinical trials on MS.3,4

Traditional visual acuity tests (the Snellen test, the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinography Study [ETDRS]) assess high-contrast visual acuity. Tests assessing low-contrast visual acuity (the Sloan test) and contrast sensitivity (the Pelli-Robson test) identify visual dysfunction not detectable in high-contrast tests in patients with MS.5,6

Pelli-Robson charts test contrast sensitivity and use a single letter size. Numerous cross-sectional studies have analysed modifications of this test in patients with MS with and without history of optic neuritis (ON) and related the results with visual evoked potentials, quality of life, MS type, level of functional impairment, and retinal nerve fibre layer thickness.7–9 However, few longitudinal studies have assessed visual function with contrast sensitivity tests or other techniques; the extant studies include short follow-up periods.10–12

The present study analyses alterations in visual function (visual acuity and contrast sensitivity) in patients with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) with and without history of ON over a follow-up period of 6 years.

Material and methodsWe performed a longitudinal, observational study of 61 patients (122 eyes) at the neuro-ophthalmology unit at Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Victoria (Málaga) between January 2010 and January 2016. In compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the confidentiality of the results was guaranteed and all patients signed informed consent forms.

Patients were grouped as follows: 1) control group: 15 healthy individuals (30 eyes); 2) patients with RRMS and no documented history of ON (this group included the eyes of patients without ON [28 patients; 56 eyes] and contralateral eyes of those patients who had presented an episode of ON [18 patients; 18 eyes]): 46 patients (74 eyes); and 3) patients with RRMS and a history of unilateral ON of over 6 months’ progression: 18 patients (18 eyes). No statistically significant differences in monocular Pelli-Robson test results were observed between the eyes of patients with no history of ON and the contralateral eyes of patients with ON (P=.154). MS was diagnosed according to the McDonald criteria.13 RRMS is defined as acute attacks or relapses of neurological alterations with full or partial recovery; no disease progression is observed in periods between relapses.14 ON was clinically defined as a sudden, unilateral loss of visual acuity accompanied by mild periorbital pain exacerbated by eye movements.15 We excluded all those patients who presented ocular hypertension, glaucoma, cataracts, uveitis, retinal detachment, diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, or any other ophthalmologic or systemic disease with potential to affect visual acuity, either at baseline or at any point during the follow-up period. Patients experiencing episodes of ON during the follow-up period were also excluded.

All patients underwent neurological and ophthalmologic examinations at the beginning and at the end of the study period. We gathered the following data: Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score; MS progression time prior to the start of the study; MS follow-up time; best visual acuity score on a Snellen chart at 6 metres; contrast sensitivity (monocular and binocular) according to a Pelli-Robson chart (Clement Clark Ltd.; Harlow, UK) at one metre, illuminated at 90 to 120cd/m2; intraocular pressure, measured using applanation tonometry; and a non-contact slit-lamp examination of the posterior segment using an 84-diopter lens (Volk; Ohio, USA).

Statistical analysisQuantitative data are expressed as means±standard deviation; qualitative data are expressed as percentages. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics, v 22.0 (IBM Corporation; Chicago, USA). Qualitative variables were compared using the chi-square test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare quantitative to non-dichotomous qualitative variables. The t test was used to compare normally-distributed quantitative variables and independent, dichotomous qualitative variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparisons involving non-normally-distributed data. For paired samples, the paired samples t test was used for normally-distributed data, and the Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used for non-normally-distributed data. Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

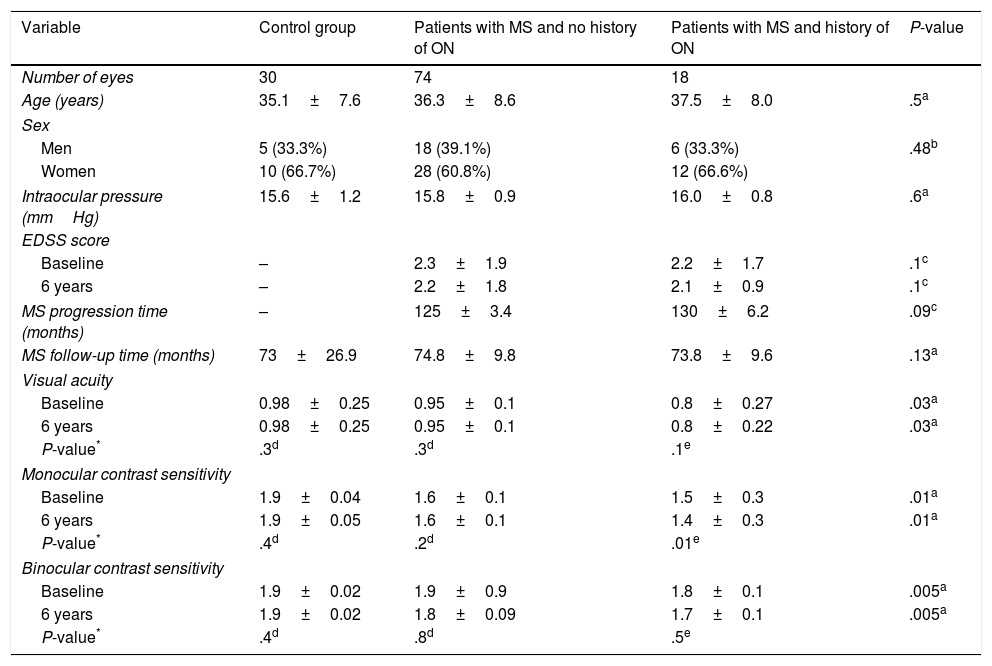

ResultsOf the 61 patients included in the study, 38 (62.2%) were women and 23 (37.7%) were men. Mean age was 36.3±8.1 years. Mean intraocular pressure was 15.8±1.01mmHg. Disease progression at the time of study inclusion was 127.5±4.84 months. Mean follow-up time was 73.8±15.4 months. Mean EDSS score was 2.26±1.84 at the beginning of the study period and 2.68±1.96 at the end. Mean visual acuity was 0.9±0.21 at the beginning of the study period and 0.9±0.17 at the end. Mean monocular contrast sensitivity was 2.06±0.19 at the beginning of the study period and 1.66±0.16 at the end. Mean binocular contrast sensitivity was 1.88±0.39 at the beginning of the study period and 1.86±0.08 at the end. Clinical characteristics for the different study groups are listed in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study participants.

| Variable | Control group | Patients with MS and no history of ON | Patients with MS and history of ON | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of eyes | 30 | 74 | 18 | |

| Age (years) | 35.1±7.6 | 36.3±8.6 | 37.5±8.0 | .5a |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 5 (33.3%) | 18 (39.1%) | 6 (33.3%) | .48b |

| Women | 10 (66.7%) | 28 (60.8%) | 12 (66.6%) | |

| Intraocular pressure (mmHg) | 15.6±1.2 | 15.8±0.9 | 16.0±0.8 | .6a |

| EDSS score | ||||

| Baseline | – | 2.3±1.9 | 2.2±1.7 | .1c |

| 6 years | – | 2.2±1.8 | 2.1±0.9 | .1c |

| MS progression time (months) | – | 125±3.4 | 130±6.2 | .09c |

| MS follow-up time (months) | 73±26.9 | 74.8±9.8 | 73.8±9.6 | .13a |

| Visual acuity | ||||

| Baseline | 0.98±0.25 | 0.95±0.1 | 0.8±0.27 | .03a |

| 6 years | 0.98±0.25 | 0.95±0.1 | 0.8±0.22 | .03a |

| P-value* | .3d | .3d | .1e | |

| Monocular contrast sensitivity | ||||

| Baseline | 1.9±0.04 | 1.6±0.1 | 1.5±0.3 | .01a |

| 6 years | 1.9±0.05 | 1.6±0.1 | 1.4±0.3 | .01a |

| P-value* | .4d | .2d | .01e | |

| Binocular contrast sensitivity | ||||

| Baseline | 1.9±0.02 | 1.9±0.9 | 1.8±0.1 | .005a |

| 6 years | 1.9±0.02 | 1.8±0.09 | 1.7±0.1 | .005a |

| P-value* | .4d | .8d | .5e | |

EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; MS: multiple sclerosis; ON: optic neuritis.

No statistically significant differences were observed for age, sex, intraocular pressure, MS progression/follow-up time, or EDSS score. However, we did observe statistically significant differences between study groups for visual acuity and monocular and binocular contrast sensitivity, both at baseline (P=.03, P=.01, and P=.005, respectively) and at the end of the study period (P=.03, P=.01, and P=.005, respectively) (Table 1).

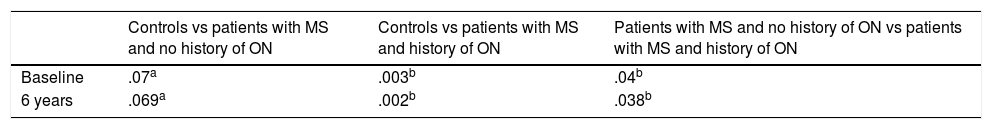

The control group and the group of patients with RRMS and no history of ON displayed significantly better visual acuity than patients displaying ON, both at the beginning (P=.003 and P=.04, respectively) and at the end of the study period (P=.002 and P=.038) (Table 2). However, no group showed differences between visual acuity measurements taken at the beginning and at the end of the study (P=.3, P=.3, and P=.1) (Table 1).

Comparison of visual acuity between study groups at baseline and at 6 months.

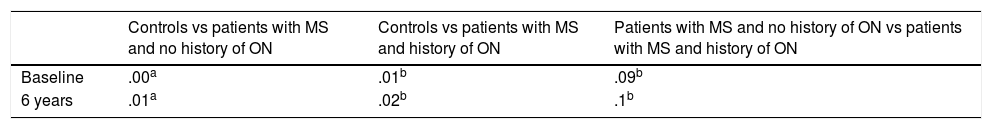

Scores for monocular contrast sensitivity were significantly lower in patients with MS with and without history of ON than in controls, both at the beginning (P=.01 and P=.00, respectively) and at the end of the study period (P=.02 and P=.01). However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the MS groups at the beginning (P=.09) or at the end of the follow-up period (P=.1) (Table 3). Only the group of patients with history of ON showed statistically significant differences between monocular contrast sensitivity measurements taken at the beginning and at the end of the study (P=.01) (Table 1).

Comparison of monocular contrast sensitivity between study groups at baseline and at 6 months of follow-up.

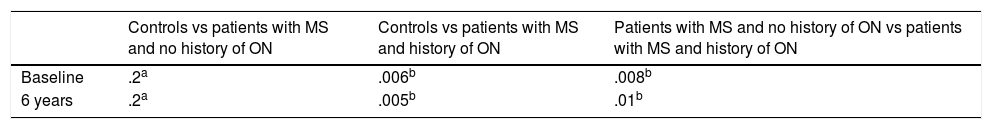

Scores for binocular contrast sensitivity were significantly lower in patients with MS with history of ON than in patients without ON and controls, both at the beginning (P=.006 and P=.008, respectively) and at the end of the follow-up period (P=.005 and P=.01) (Table 4). However, no group showed statistically significant differences between Pelli-Robson scores as measured at the beginning and at the end of the study (P=.4, P=.8, and P=.5) (Table 1).

Comparison of binocular contrast sensitivity between study groups at baseline and at 6 months of follow-up.

ON, an inflammatory neuropathy of the optic nerve, constitutes the first symptom of MS in 20% of cases.15 In our study, patients with ON had poorer visual acuity than the remaining participants, both at baseline and at 6 years of follow-up. Our results are consistent with the findings of Cennamo et al.16 and Saxena et al.,17 but contradict those reported by Oreja-Guevara et al.18 and Waldman et al.,19 who observed no statistically significant differences in visual acuity between patients with and without ON. Recovery of visual acuity generally begins at 2 weeks, with full recovery at 6 months.20 Mean symptom progression among patients with history of ON in our study was longer than 6 months. Mean visual acuity for patients with ON remained stable at 0.8 (equivalent to an ETDRS score of 20/25) throughout the study period.21 In the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial, 85% of patients with ON had a mean visual acuity greater than 20/25 10 years after the episode.22 Therefore, it would appear that patients with history of ON in our sample have good visual acuity, with some level of residual vision loss compared to patients without neuritis.

Trobe et al.23 describe a recovery of visual acuity in 75% of patients with MS and a history of ON; however, 55.7% of these patients had abnormal results in a contrast sensitivity test performed a year after the episode. Controls showed better monocular contrast sensitivity than patients with MS with and without history of ON, both at the beginning and at the end of the study period. Fisher et al.,24 Waldman et al.,19 and Merle et al.25 also observe reduced monocular contrast sensitivity in patients with MS and ON compared to those without ON. However, we observed no statistically significant differences between the groups with and without ON. In a study of 29 controls and 22 patients with MS (8 with history of ON), Waldman et al.19 found poorer binocular contrast sensitivity in patients with a history of ON. These results are consistent with our own; patients with ON in our sample also presented poorer binocular contrast sensitivity than those with MS but not ON.

A literature review (PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases; search terms: “multiple sclerosis,” “optic neuritis,” “contrast sensitivity,” and “Pelli-Robson”) identified only one longitudinal study of Pelli-Robson test results in patients with MS. Narayanan et al.12 used Pelli-Robson charts to study contrast sensitivity in 57 patients with RRMS over a 2-year follow-up period. Statistical analysis detected no significant differences in monocular contrast sensitivity at the beginning and at the end of the study period in patients with ON of over 6 months’ progression or patients without ON. However, a statistically significant improvement was seen between scores at the beginning and at the end of the study period in eyes with ON of less than 6 months’ progression. Our 6-year results for the group of patients with history of ON show significantly poorer scores in the Pelli-Robson test. The differences between our findings and those of Narayanan et al.12 for this patient group may be due to the difference in the follow-up periods (6 vs 2 years), which could affect test results, or to the level of functional disability: Pelli-Robson scores decrease as MS becomes more severe.26

Researchers including Herrero et al.,27 García-Martín et al.,28 and Narayanan et al.29 have studied changes in mean retinal nerve fibre layer thickness in patients with MS with different follow-up periods, concluding that there is a statistically significant, progressive decrease in this parameter in these patients with respect to controls. New protocols, such as the Spectralis “Nsite axonal analytics” software, are now available for the study of neurodegenerative diseases; these techniques appear to be more sensitive than traditional protocols for detecting nerve fibre layer alterations secondary to neurodegenerative disease.30

The main limitation of the present study is the sample size; further studies should include greater numbers of patients. Secondly, while no statistically significant differences were observed in MS progression time, future longitudinal studies should ensure uniformity in this parameter.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that measuring visual acuity with the Snellen test is not effective for assessing visual pathway alterations in patients with MS. Contrast sensitivity may progressively deteriorate in patients with a history of ON, even in the absence of additional ON episodes. This deterioration is not observed in eyes with no history of ON. The Pelli-Robson test may therefore be used to assess the deterioration of visual function in patients with MS and history of ON.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: González Gómez A, García-Ben A, Soler García A, García-Basterra I, Padilla Parrado F, García-Campos JM. Estudio longitudinal de la función visual en pacientes con esclerosis múltiple remitente-recurrente con y sin antecedentes de neuritis óptica. Neurología. 2019;34:241–247.