The main challenge of Parkinson’s disease in women of childbearing age is managing symptoms and drugs during pregnancy and breastfeeding. The increase in the age at which women are having children makes it likely that these pregnancies will become more common in future.

ObjectivesThis study aims to define the clinical characteristics of women of childbearing age with Parkinson’s disease and the factors affecting their lives, and to establish a series of guidelines for managing pregnancy in these patients.

ResultsThis consensus document was developed through an exhaustive literature search and a discussion of the available evidence by a group of movement disorder experts from the Spanish Society of Neurology.

ConclusionsParkinson’s disease affects all aspects of sexual and reproductive health in women of childbearing age. Pregnancy should be well planned to minimise teratogenic risk. A multidisciplinary approach should be adopted in the management of these patients in order to take all relevant considerations into account.

El manejo de la enfermedad de Parkinson en la mujer en edad fértil nos plantea como principal reto el manejo de la enfermedad y los fármacos durante el embarazo y lactancia. El aumento de la edad gestacional de la mujer hace más probable que la incidencia de embarazos pueda incrementarse.

ObjetivoDefinir las características clínicas y los factores que condicionan la vida de la mujer en edad fértil con enfermedad de Parkinson y definir una guía de actuación y manejo del embarazo en estas pacientes.

DesarrolloEste documento de consenso se ha realizado mediante una búsqueda bibliográfica exhaustiva y discusión de los contenidos llevadas a cabo por un grupo de expertos en trastornos del movimiento de la Sociedad Española de Neurología.

ConclusionesLa enfermedad de Parkinson afecta a todos los aspectos relacionados con la salud sexual y reproductiva de la mujer en edad fértil. Se debe planificar el embarazo en las mujeres con enfermedad de Parkinson para minimizar los riesgos teratogénicos sobre el feto. Se recomienda un abordaje multidisciplinar de estas pacientes para tener en cuenta todos los aspectos implicados.

Women of childbearing age present a series of characteristics that influence not only their health but also the course of diseases they may present. In this population group, disease is influenced by biological factors related to sex, gender, and other social determinants.

Movement disorders are a heterogeneous group of diseases, with age of onset ranging from childhood to old age. As onset occurs during childbearing age in many women, it is important to understand and know how to manage these diseases in this stage of life.

A panel of experts belonging to the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Movement Disorders Study Group has prepared a consensus statement aiming to improve the diagnosis and treatment of movement disorders in women of childbearing age, and particularly during pregnancy and breastfeeding, given the risks and responsibilities associated with these situations.

The document is based on a comprehensive review of articles published on the Brain, PubMed, Web of Science, PEDro, Scopus, CINAHL, and ScienceDirect databases, as well as the authors’ clinical experience. We identified relevant articles addressing subjects related to Parkinson’s disease (PD) during pregnancy, applying no filters based on year of publication, language, or study limitations. Based on the findings of the review, all the authors of the study agreed on a series of recommendations intended to assist in the management of movement disorders during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

In part 1, we address the characteristics of women of childbearing age with PD. This review places special emphasis on the management of pregnant women with PD and on rational, evidence-based management of the drugs used to treat the disease.

Between 5% and 7% of Western patients with PD (10%-14% in Japan) are diagnosed before the age of 55 years; these patients are considered to have young-onset PD.1 The incidence of pregnancy in patients with PD is low and poorly understood, as the disease most frequently affects patients older than 50 years. The increase in the age at which women are having children makes it likely that incidence of pregnancy in these patients will increase in future. PD has a greater effect on quality of life in patients younger than 45 years, with a clear impact on family, personal, and work activities.2

Sexual health in women with Parkinson’s diseaseVery few studies have been conducted into sexual health in women with PD, partly due to social and cultural issues.3 Sexual problems in these patients are complex, with the motor and non-motor symptoms of the disease, the secondary effects of some drugs, and potential cognitive, behavioural, and emotional involvement all playing an important role.

Population studies suggest that 84% of women with PD present reduced libido and 75% have difficulty reaching orgasm.4 Some signs and symptoms of PD (eg, bradykinesia, rigidity, difficulty turning in bed, sialorrhoea, hyperhidrosis, seborrhoea, and hypomimia) often make patients feel self-conscious. Sleep alterations, such as REM sleep behaviour disorder, periodic limb movement disorder, and restless legs syndrome, can force couples to sleep in separate beds or rooms. Depression, cognitive impairment, and delusions (particularly delusions of jealousy) can also influence sexual health. Fear of rejection can prevent patients from approaching their partners sexually, while their partners may also feel ignored. PD is also associated with greater prevalence of vaginal dryness, resulting in painful intercourse and vaginismus. All these factors affect the quality of patients’ sex lives.5 Some women receiving dopaminergic agonists (0.5%) may present hypersexuality; we should be vigilant to the appearance of this symptom in order to withdraw the drug promptly.

Few studies have evaluated the potential for drug interactions involving contraceptives and antiparkinsonian drugs. Bioequivalence studies with rotigotine and oral contraceptive drugs have detected no relevant interactions.6 In any case, it should be noted that in general, some drugs can induce expression of such liver enzymes as cytochrome P450, which accelerate the conversion of oral contraceptives into metabolites with reduced biological activity, making it necessary to consider double barrier contraception.

Prolonged use of oral contraceptives or menopausal hormones may be associated with increased risk of developing PD; however, more studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.7

Individualised, multidisciplinary pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment is the key to success. It is helpful to follow an individual care plan to assist patients and their partners in solving specific problems, which may change over the course of the disease and can include feelings of loss or guilt, changes to body image, and shifts in each partner’s roles in the relationship.

Reproductive health in women with Parkinson’s diseaseReproductive health is defined as the physical, mental, and social well-being related to the reproductive system.

Factors related to reproduction in Parkinson’s disease. Few studies have been conducted into reproductive milestones in patients with PD, and their results are inconclusive.3 Women with PD seem to be older at menarche and to present more premenstrual symptoms and dysmenorrhoea than those without the disease. Duration of the reproductive period, age at menopause, and form of onset of menopause are similar in women with and without PD, although women with PD present more hot flushes. Women with PD also tend to have fewer children and miscarriages, and less frequently use oral contraceptives.

Reproductive factors and the risk of developing PD. The impact of female reproductive factors on the risk of developing PD is poorly understood. One study found no association between PD and age at menarche and menopause, duration of the reproductive period, cumulative length of pregnancy, hormone replacement therapy, or surgical menopause, although use of oral contraceptives did show a positive association with PD.8 However, a meta-analysis of 11 observational studies found that PD was not associated with age at menarche or at menopause, duration of the reproductive period, parity, or oral contraceptive use.9

Reproductive factors and age of onset of PD. Certain reproductive factors (eg, number of pregnancies, duration of the reproductive period, cumulative length of pregnancy, number of children, and age at menopause) have been associated with later disease onset10,11; this may explain the lower incidence of PD among women and suggest a protective role of oestrogens.

Effects of pregnancy on the symptoms and progression of Parkinson’s diseaseFew data have been published on PD and pregnancy. The incidence of pregnancy among patients with PD is also unclear.

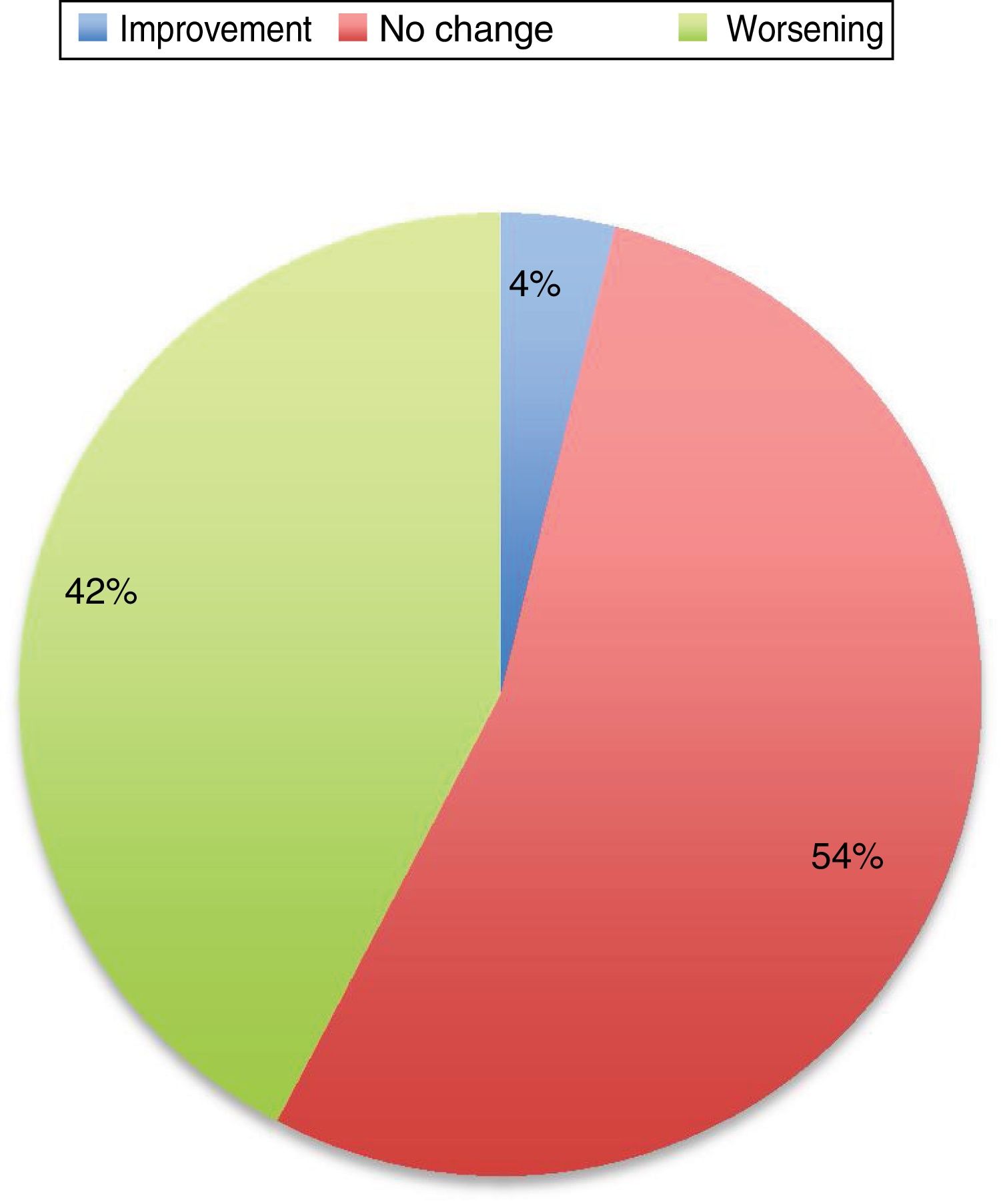

The first series was published in 1987, and included 24 pregnancies12; the second series, including 35 pregnancies, was not published until 1998.13 In most cases (65% in the study by Kranick et al.12 and 45% in the study by Hagell et al.13), PD worsens during pregnancy, and some of these patients do not recover their pre-pregnancy status. Almost a quarter of these patients used no medication during pregnancy.

A subsequent review of cases published until 2016 includes 74 pregnancies.3 PD did not worsen in 52% of patients, and improved in some cases. Eighty-three percent of patients continued taking antiparkinsonian medications; of these, 64% showed improvement or no change in PD symptoms, and up to 33% of those who suspended treatment also experienced an improvement. However, these data are heterogeneous, with each article using different measures of the status of the disease and including patients at different stages of pregnancy and disease progression, of different ages, and receiving different drugs.

Symptoms worsened in 36% of cases in this series. The reason that some patients present clinical worsening despite continuing with treatment is unclear. It may be explained by physiological changes, such as increased plasma volume, volume of distribution, and metabolic state, which may result in subtherapeutic levels of the medication. Changes in diet and intestinal absorption may also play a role. The physical and psychological stress involved in pregnancy may be another factor. The role of oestrogens is complex. Oestrogens seem to have a protective effect on dopaminergic neurons. Oestriol is the dominant oestrogen during pregnancy, whereas oestradiol is predominant during most of the reproductive period; the latter has greater affinity for oestrogen receptors and seems to play a neuroprotective role.3 Twelve percent of the remaining patients presented no change in their situation. Several recent series have also addressed this issue, and report very similar data (Fig. 1).

Changes in motor status in Parkinson’s disease during pregnancy.29

In general, the published data suggest that women who receive treatment during pregnancy present better disease progression than those who do not. Good motor function is extremely important, particularly in the period prior to delivery and in the postpartum period.

Potential effects of Parkinson’s disease on pregnancyIn women with PD, we may expect many symptoms of pregnancy to be exacerbated, particularly those that existed prior to pregnancy as a result of PD. For example, such non-motor symptoms as anxiety or depression, sialorrhoea, circadian rhythm alterations, or gastrointestinal problems including vomiting or constipation may be more pronounced in pregnant women, as these symptoms are characteristic of both pregnancy and PD. Likewise, instability due to parkinsonism may be exacerbated in pregnant patients, who present greater mobility problems due to weight gain and the change in their centre of gravity.

The current evidence suggests that, beyond complications during pregnancy, PD seems not to affect fertility, conception, or delivery: a lower rate of caesarean sections has been reported in women with PD than in the general population.14

Neither has any study clearly demonstrated increased incidence of miscarriage or fetal anomalies in patients with PD. In fact, a study of 75 full-term neonates reports only 3 cases of fetal anomalies (osteomalacia, ventricular septal defect, and inguinal hernia); all 3 children were born to mothers who were receiving antiparkinsonian drugs.3

Therefore, we may conclude that PD can exacerbate the typical complaints during pregnancy, but does not increase the rate of severe complications.

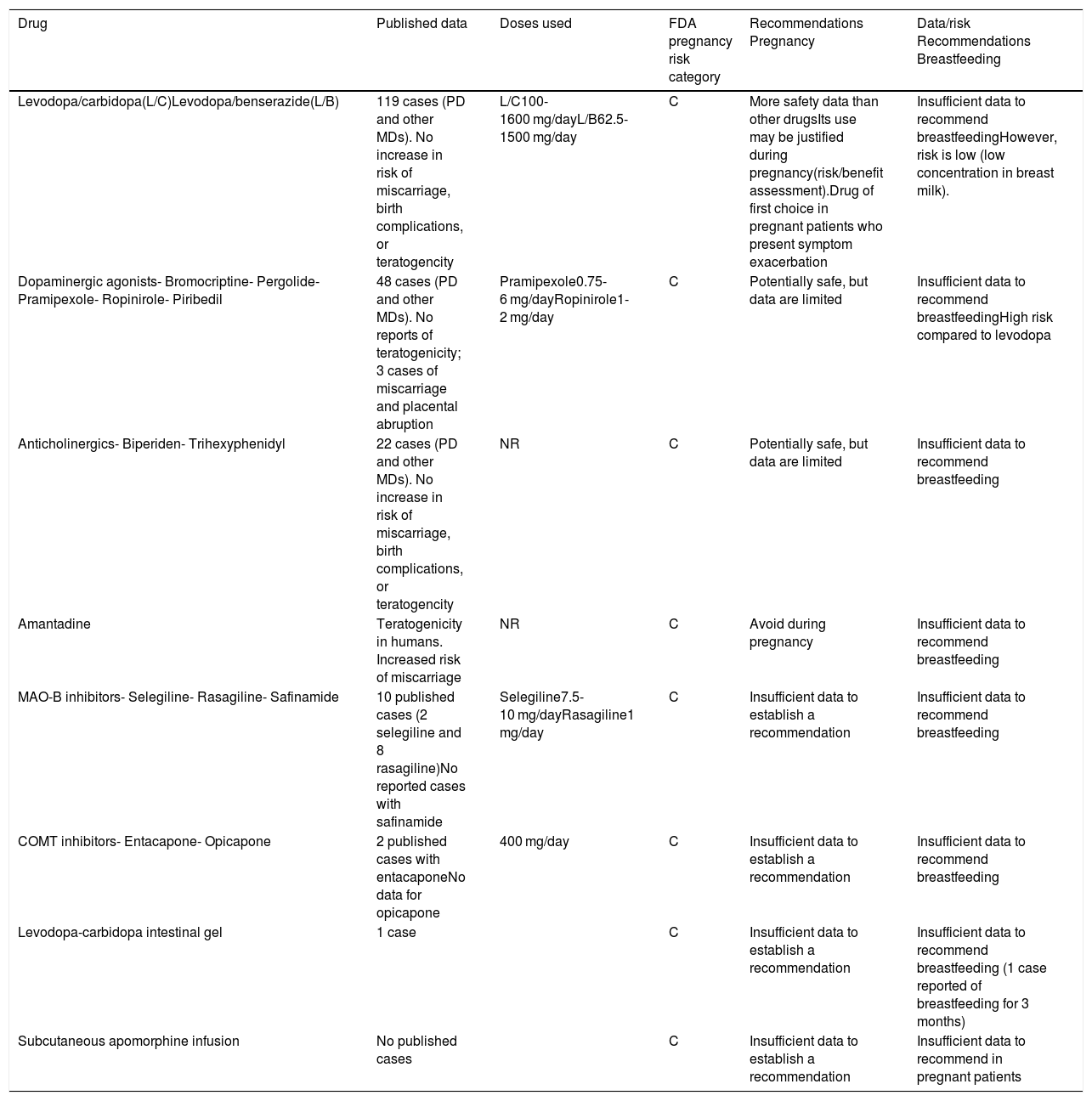

Antiparkinsonian treatment during pregnancyFew studies have described the effects of dopaminergic drugs on pregnancy or their teratogenic potential; the literature on this subject includes only case reports and small series. Furthermore, the samples included are heterogeneous in terms of patient age and drug types and combinations, which prevents us from drawing firm conclusions. Regarding exposure time, it is common when patients become pregnant for doses to be reduced or for some drugs to be suspended, resulting in motor impairment that frequently leads to reintroduction of the drug (Table 1).

Summary of the recommendations for the main drugs used in movement disorders during pregnancy and breastfeeding.3,12,14,30–32

| Drug | Published data | Doses used | FDA pregnancy risk category | Recommendations Pregnancy | Data/risk Recommendations Breastfeeding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levodopa/carbidopa(L/C)Levodopa/benserazide(L/B) | 119 cases (PD and other MDs). No increase in risk of miscarriage, birth complications, or teratogencity | L/C100-1600 mg/dayL/B62.5-1500 mg/day | C | More safety data than other drugsIts use may be justified during pregnancy(risk/benefit assessment).Drug of first choice in pregnant patients who present symptom exacerbation | Insufficient data to recommend breastfeedingHowever, risk is low (low concentration in breast milk). |

| Dopaminergic agonists- Bromocriptine- Pergolide- Pramipexole- Ropinirole- Piribedil | 48 cases (PD and other MDs). No reports of teratogenicity; 3 cases of miscarriage and placental abruption | Pramipexole0.75-6 mg/dayRopinirole1-2 mg/day | C | Potentially safe, but data are limited | Insufficient data to recommend breastfeedingHigh risk compared to levodopa |

| Anticholinergics- Biperiden- Trihexyphenidyl | 22 cases (PD and other MDs). No increase in risk of miscarriage, birth complications, or teratogencity | NR | C | Potentially safe, but data are limited | Insufficient data to recommend breastfeeding |

| Amantadine | Teratogenicity in humans. Increased risk of miscarriage | NR | C | Avoid during pregnancy | Insufficient data to recommend breastfeeding |

| MAO-B inhibitors- Selegiline- Rasagiline- Safinamide | 10 published cases (2 selegiline and 8 rasagiline)No reported cases with safinamide | Selegiline7.5-10 mg/dayRasagiline1 mg/day | C | Insufficient data to establish a recommendation | Insufficient data to recommend breastfeeding |

| COMT inhibitors- Entacapone- Opicapone | 2 published cases with entacaponeNo data for opicapone | 400 mg/day | C | Insufficient data to establish a recommendation | Insufficient data to recommend breastfeeding |

| Levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel | 1 case | C | Insufficient data to establish a recommendation | Insufficient data to recommend breastfeeding (1 case reported of breastfeeding for 3 months) | |

| Subcutaneous apomorphine infusion | No published cases | C | Insufficient data to establish a recommendation | Insufficient data to recommend in pregnant patients |

C: human studies have shown no adverse effects on the fetus. No controlled studies have been performed in pregnant women. Risk-benefit assessment must be performed before prescribing.

Levodopa is the most widely used and the safest drug. A review performed in 2017 described 114 women (46 with PD) receiving levodopa dosed between 100 and 2500 mg, with treatment duration ranging from several weeks to the entire pregnancy.3 Among these patients, only 8 cases of minor complications were reported, including spotting in the first trimester, neonate presenting a seizure after birth, preeclampsia, osteomalacia, ventricular septal defects, placental abruption, and transient hypotonia. In most cases, levodopa was combined with other dopaminergic drugs. In a 2018 study of a series of 14 patients, 5 of whom were treated with levodopa, the only complication reported was a case of neonatal respiratory distress.14 Subsequent development was completely normal in all neonates. The incidence of miscarriage and preeclampsia was no greater than that expected in the general population.14

Dopaminergic agonistsLittle evidence is available on the safety of this group of drugs in PD. They are very widely used to treat hyperprolactinaemia, and no complications of pregnancy or teratogenic effects have been reported in this context. A German registry of pregnancies, in which most patients were treated for restless legs syndrome, reports 21 pregnancies without complications.5 However, these data are difficult to extrapolate as low doses were used in both groups, and all the women with hyperprolactinaemia and many of those with restless legs syndrome suspended treatment when they became aware they were pregnant.

Barely 30 cases have been reported of treatment with dopaminergic agonists in pregnant patients with PD; the only complications reported are one case of placental abruption in a patient who received cabergoline; neonatal seizures in a child born to a patient who received bromocriptine; and one miscarriage, one case of Down syndrome, and one neonatal death due to severe liver deficiency in a twin pregnancy, all 3 born to mothers who received pramipexole.3,14 Causality was not clearly demonstrated in any case.

MAO-B inhibitors and COMT inhibitorsFew data are currently available on other dopaminergic drugs. Two cases have been published of patients who received selegiline, with one neonate born with a ventricular septal defect (the mother was also receiving levodopa and entacapone).3 In a Turkish series including 7 patients receiving rasagiline, one newborn died due to severe liver failure; 6 patients continued receiving the drug throughout the period of organogenesis, with no cases of fetal abnormalities. Rasagiline undergoes hepatic metabolism by the cytochrome P450 system; however, no cases of liver failure have been reported.14 No data have been published on the use of safinamide in pregnant women.

One case has been reported of entacapone use during pregnancy; no complications were recorded, despite the teratogenic effects observed in animal studies.15 No data have been published on the use of opicapone in pregnant women. Animal studies provide insufficient data on reproductive toxicity. In rats, opicapone administered at doses 22 times higher than the therapeutic level in humans had no effect on fertility in male or female animals, or on prenatal development. In pregnant rabbits, the drug was less well tolerated, reaching maximal systemic exposure levels near or below the therapeutic range. While embryonic/fetal development was not negatively affected in rabbits, this study is not considered to be predictive for assessing the risk associated with the drug.

AmantadineAnimal studies suggest that the drug may have embryotoxic and teratogenic effects. In humans, 2 cases have been reported of newborns with congenital heart defects after exposure to amantadine at least during the weeks of organogenesis.16 Several cases have also been reported of pregnancies carried to term with healthy neonates.14 The authors recommend avoiding amantadine during pregnancy.

AnticholinergicsMinor defects have been described in patients treated with anticholinergics for other conditions; in the 8 patients with PD, no complications occurred and the neonates developed normally.14

In conclusion, while very limited information is available, we are able to offer guidance on the use of these drugs. Firstly, it is evident that PD must be treated during pregnancy. Regarding drug selection, the use of levodopa has been most widely reported; this is also the safest and therefore the most recommended drug. Dopaminergic agonists also seem to be safe, with no fetal abnormalities associated with their use. On the contrary, we cannot establish any conclusions on monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors, or anticholinergics due to a lack of evidence. Finally, it should be noted that the published data suggest that amantadine should be avoided during pregnancy.

Other drugs for managing Parkinson’s disease during pregnancySerotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors seem not to increase the risk of miscarriage or birth defects, but are associated with low birth weight and poor neonatal adaptation. These drugs are also associated with a slight increase in the risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension and heart defects in the neonate. Tricyclic antidepressants also seem not to be associated with an increase in congenital malformations or pregnancy complications, although they do appear to affect neonatal adaptation. The long-term neurological and psychiatric effects are unknown, as most studies only consider the first years of life. Benzodiazepines should be avoided during pregnancy, as they are associated with cleft lip and palate defects when used in the first trimester, and muscle flaccidity, hypo- or hypertonia, hypothermia, respiratory problems, and neonatal abstinence syndrome when used in the third trimester. Instead of these drugs, non-pharmacological approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy are recommended.17,18

Like in the general population, treatment of constipation includes abundant fluid intake and such osmotic laxatives as polyethylene glycol and lactulose. Polyethylene glycol (United States Food and Drug Administration [FDA] pregnancy risk category C) presents minimal systemic absorption; it is therefore unlikely to cause fetal abnormalities. Lactulose (FDA pregnancy risk category B) can also be used during pregnancy, if needed.19

Second-line treatments for Parkinson’s disease during pregnancySecond-line treatments are mainly indicated for patients with advanced PD. In the light of this, and given the low incidence of pregnancy in women with PD,3 cases of pregnancy coinciding with these treatments are even more anecdotal, particularly with regard to perfusion treatments, which are usually prescribed to older patients at later stages of disease progression. Advanced PD is even more unfavourable for self-care in all 3 trimesters, for delivery of the baby, and for subsequent care of the neonate.

Women receiving second-line treatments for advanced PD who express a desire to have children should be given individualised information on the risks involved; it is essential to assess whether they have adequate social/family or caregiver support. Whichever the second-line treatment used, treatment should be optimised in pregnant women with PD to reduce motor complications at each stage; pregnancy should be considered high-risk, and these women should be closely followed up by the neurology and gynaecology departments.3

Deep brain stimulation and ablative lesionsDeep brain stimulation. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an effective therapy in patients with advanced PD. The potential benefits for pregnant patients are a reduction in doses of antiparkinsonian medication and improvements in well-being and quality of life.

The few series published, which mainly include patients with PD9 or dystonia,8 show that most pregnancies were carried to term without complications for the fetus; few caesarean sections were performed, and some patients were able to dramatically reduce the intake of drugs, many of which have been shown to present some degree of teratogenicity (FDA pregnancy risk category C). Some authors even consider DBS an ideal therapy in younger women, as it enables management of the disease without using these drugs in patients who become pregnant. It should be noted that such symptoms as orthostatic hypotension can be exacerbated during pregnancy in patients with parkinsonism.20 Reduction or elimination of antiparkinsonian drugs following surgery may improve this symptom.

Abdominal or subclavicular placement of the pulse generator can have negative consequences in these patients. Many patients with the generator implanted in the abdominal wall reported local discomfort and a feeling of “tension” in the skin; therefore, subclavicular placement seems more suitable. However, we must also be aware that implantation in this location can also cause discomfort and difficulties with breastfeeding. In patients undergoing caesarean section, the stimulator is switched off prior to the procedure and switched back on immediately after delivery to avoid interference in the monitoring of both mother and fetus.8

Neuroablative lesions.Gamma-knife and high-intensity focused ultrasound. The potential benefits of these techniques for pregnant women are the same as those of DBS: the reduction or elimination of drugs during pregnancy. However, they do not present the other major advantage of DBS, the ability to adjust stimulation parameters. No cases have been published of the use of these techniques in pregnant women with dystonia or PD.

Continuous infusion of intestinal levodopa and subcutaneous apomorphineContinuous intestinal infusion of levodopa. Levodopa is the most widely used drug in pregnant women with PD, although the evidence on its safety is weak, and the drug can cross the placenta.3,10 We identified only one case of a patient with advanced PD receiving continuous intestinal infusion of levodopa who became pregnant with a levodopa dose of 1100 mg/day, and who was followed up as a high-risk pregnancy.11 Dyskinesia worsened during pregnancy, possibly due to COMT inhibition caused by the oestrogenic state or by other pharmacokinetic mechanisms, and the rate of infusion had to be reduced.3,11 The dose also had to be adjusted during delivery to improve labour, as she presented dyskinesia alternating with severe “off” periods. A healthy baby was delivered during an “on” period with dyskinesia, after normal vaginal delivery without complications, although the infant presented slow growth in the following months. The patient presented no complications related to the device or the stoma.11 In the event of complications due to continuous intestinal infusion of levodopa during pregnancy, we should account for the fact that endoscopic procedures are associated with potential risks to the fetus.21

Continuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusion. We identified no published case of pregnancy coinciding with continuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusion to treat advanced PD. As previously mentioned, motor complications must always be prioritised and managed on an individual basis; nonetheless, even less evidence is available on the use of dopaminergic agonists during pregnancy than for levodopa.3

Measures to adopt and neurological follow-up during a planned pregnancyMotor symptoms of PD will worsen during pregnancy in approximately half of cases. This exacerbation may be attributed to various causes, including the social and psychological stress and physiological changes associated with pregnancy, disease progression, and the effects of oestrogens.22 Worsening of motor symptoms is less pronounced in women who continue and adjust dopaminergic treatment during pregnancy; therefore, this treatment should be continued throughout pregnancy.3 Close follow-up is needed during pregnancy to enable precise adjustment of dopaminergic medication. No recommendations have been made on the frequency of review consultations during pregnancy; follow-up should be individualised and based on each patient’s needs.

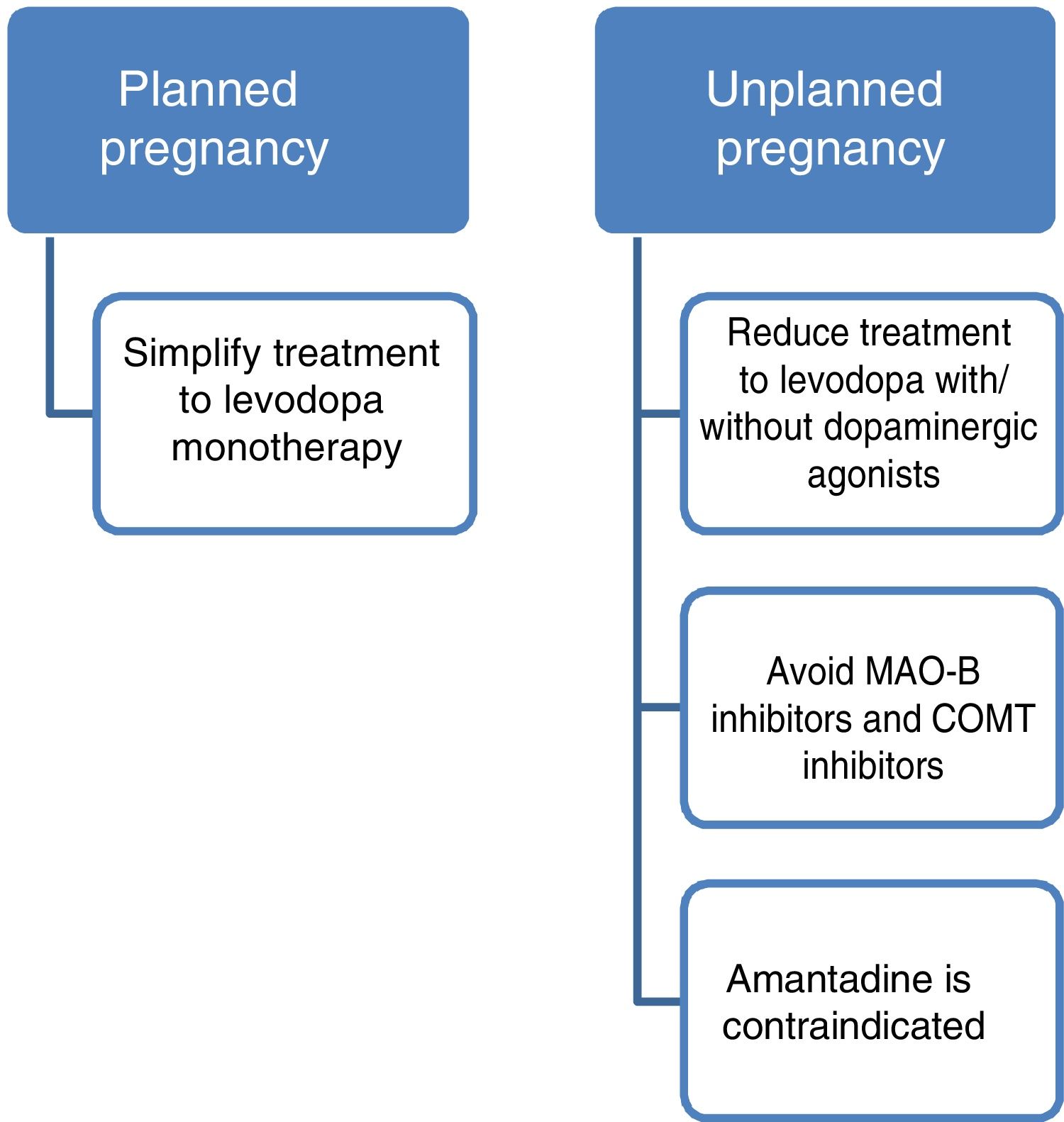

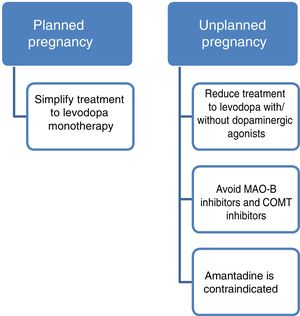

Current data support the use of levodopa as the first treatment option in pregnant patients with PD presenting exacerbation of motor symptoms.3,23 If a patient becomes pregnant, such drugs as amantadine should be avoided due to teratogenicity and increased risk of miscarriage. In patients planning to become pregnant, amantadine should be suspended in advance, or when pregnancy is confirmed. MAO-B inhibitors and COMT inhibitors should also be avoided due to a lack of evidence on their use in this population. Furthermore, current data are insufficient to support the routine recommendation of dopaminergic agonists or anticholinergics during pregnancy, despite the absence of known teratogenic effects.3,14 Given all this information, and despite the lack of guidelines on the subject, women with PD who plan to become pregnant should receive levodopa in monotherapy, with dose adjustments made according to clinical progression. The use of such other drugs as dopaminergic agonists or anticholinergics should be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

PD does not increase the risk of complications during delivery; therefore, there is no need to schedule caesarean section on the basis of PD alone. Similarly, miscarriage rates are not increased in this patient group (Fig. 2).3

Puerperium and breastfeedingPuerperium is the period in which the reproductive system fully recovers following childbirth. Some general symptoms of PD can be exacerbated during this period. Constipation can worsen, and there is increased risk of urinary problems or haemorrhoids. A diet rich in fibre and abundant fluid intake seem advisable. Depression may also appear or worsen in this period. Cases have been described of PD onset during puerperium. Some cases were initially misdiagnosed as being psychogenic or as postpartum depression; it is therefore important to ensure proper evaluation of such motor symptoms as tremor or slowness of movement in the postpartum period, with or without depression, as well as close follow-up of psychological and affective problems.24

Breast milk is indicated as a complete food source until 6 months of age, and to supplement other foods until 2 years of age.25 Insufficient evidence exists on the effect of PD on breastfeeding and the safety of breastfeeding when the mother is receiving antiparkinsonian medication.3

Levodopa, amantadine, entacapone, and tolcapone are excreted in breast milk, and the potential effects on the infant are unknown. Breastfeeding should be avoided in patients receiving these drugs. No data are available on the excretion of opicapone in breast milk, or the potential effects on the infant. Levodopa and dopaminergic agonists may inhibit the release of prolactin, and therefore of breast milk. The degree to which these drugs are excreted in milk is unknown; therefore, breastfeeding is not recommended in patients receiving them. Data are also lacking on the excretion of MAO-B inhibitors in breast milk and their effect on the infant, so patients taking these drugs should also be advised against breastfeeding. Three cases have been reported of breastfeeding in patients treated with oral or duodenal levodopa. In one patient, the dose ingested by the infant was determined, and was very low.24 Domperidone is excreted at low concentrations and has an unknown effect on the infant; therefore, caution should be exercised when prescribing the drug.

One case has been described of treatment with continuous intestinal infusion of levodopa during lactation; the treatment was maintained for 3 months, and while the infant showed slow growth, no developmental delays were observed.5

In conclusion, more studies on pregnancy and puerperium in patients with PD would enable us to improve clinical practice in this rare situation. However, given the gaps in our understanding of the effects of these drugs on infants, breastfeeding is not advisable in women with PD.

Genetic counselling in Parkinson’s diseaseBoth genetic and environmental factors are involved in PD pathogenesis, although genetics only explains 10% of cases.26 Good genetic counselling requires analysis of family history of PD to determine whether the disease is sporadic or familial; dominant or recessive inheritance is established according to the gene involved and the associated clinical picture. Genetic testing is currently recommended for women of childbearing age with typical PD and clear family history of the condition, showing dominant inheritance, or with sporadic PD with onset before 40 years of age. Identifying the causal gene in familial PD enables us to offer personalised care, as well as specific genetic counselling on the risk of recurrence in the family.27,28 As some mutations display incomplete penetrance, and given the lack of disease-modifying treatments or gene therapies for PD, genetic testing of asymptomatic relatives should be performed with caution due to the ethical and personal implications.

ConclusionsIn women of childbearing age, PD affects all aspects of sexual and reproductive health. Management of these patients should follow a multidisciplinary approach, and these aspects should be taken into consideration during the comprehensive treatment of the disease. In patients planning to become pregnant, antiparkinsonian treatment should be adjusted to minimise the potential risk of teratogenic effects. Genetic counselling should be offered and pregnancy should be considered high-risk, with close follow-up by the obstetrics department.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: García-Ramos R, Santos-García D, Alonso-Cánovas A, et al. Manejo de la enfermedad de Parkinson y otros trastornos del movimiento en mujeres en edad fertil: Parte 1. Neurología. 2021;36:149–158.