Nilotinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that has been approved as a treatment for chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML). Nilotinib has been associated with increased risk of peripheral artery disease (PAD),1–3 coronary artery disease, and cerebrovascular events.4–6 We present the cases of 3 patients who experienced ischaemic strokes during long-term treatment with nilotinib. Two of them also presented PAD and intracranial atherosclerosis. The third had dissection of the internal carotid artery (ICA) with no evidence of atheromatosis in the vascular study. At the time of stroke, the 3 patients showed high 10-year cardiovascular risk (CVR) according to the instrument developed by the American Heart Association (AHA).7

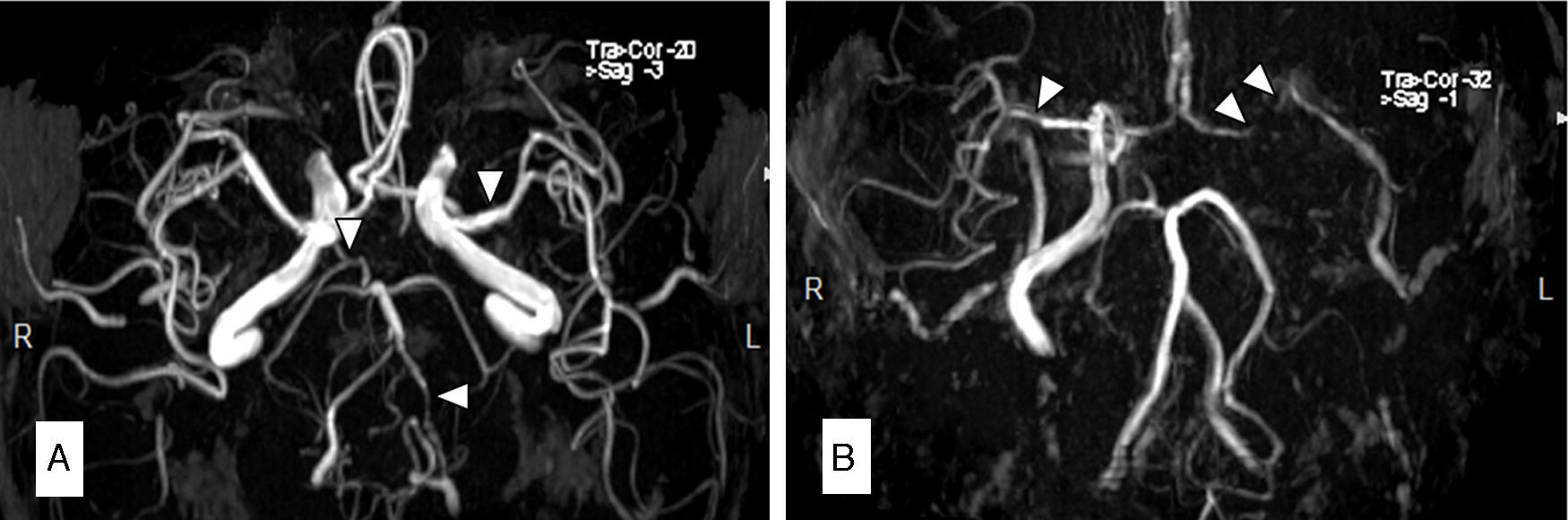

Description of the 3 casesCase 1Our first patient was a 66-year-old man with a history of arterial hypertension and CML; he had been treated with nilotinib 400mg twice daily throughout the previous 8 months. His 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) was 9.6%. The patient visited our hospital due to sudden onset of vertigo, diplopia, central facial palsy, and gait ataxia. An MRI scan revealed multiple acute ischaemic lesions in the midbrain, pons, and occipital cortex. MR angiography (MRA) showed occlusion of the vertebral artery and significant intracranial atherosclerosis (Fig. 1A). Treatment was changed to dasatinib and oral anticoagulant treatment with acenocoumarol was added. Eight months later, the patient was diagnosed with PAD and had a stent placed in his femoral artery.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) in patient 1 (A) showed occlusion of the left vertebral artery (VA) and intracranial diffuse atherosclerosis, especially in the right VA, the left MCA, and the right posterior cerebral artery (PCA). The MRA in patient 2 (B) showed a lack of circulation in the left ICA and MCA, with intracranial atherosclerosis predominantly affecting the right MCA and PCA.

The second patient was a male smoker aged 56 with a history of arterial hypertension and coronary artery disease. Five years before the admission in question, he was diagnosed with CML and treated with nilotinib 300mg twice daily. Sixteen months before being admitted, the patient presented occlusion of the central retinal artery. Treatment with nilotinib was therefore suspended in favour of antiplatelet and lipid-lowering agents. His 10-year ASCVD risk was 14.8%. The patient was admitted following multiple self-limiting episodes of dysarthria, hemiparesis, and hemihypaesthesia. The vascular study showed near occlusion of the left ICA and stenosis of the right ICA and both middle cerebral arteries (MCA). We initiated anticoagulant treatment with intravenous sodium heparin. Despite treatment, the patient showed further symptoms of hemiplegia and aphasia due to left ICA occlusion. Emergency angioplasty and stent placement failed to result in clinical improvement. An ultrasound study 2 days later showed stent occlusion. MR angiography confirmed lack of flow in the left ICA and MCA. The patient remained on anticoagulant treatment with acenocoumarol after discharge. His NIHSS score was 7 in a follow-up assessment completed at 3 months. He had not experienced any new vascular events at that time and we decided to replace acenocoumarol with aspirin.

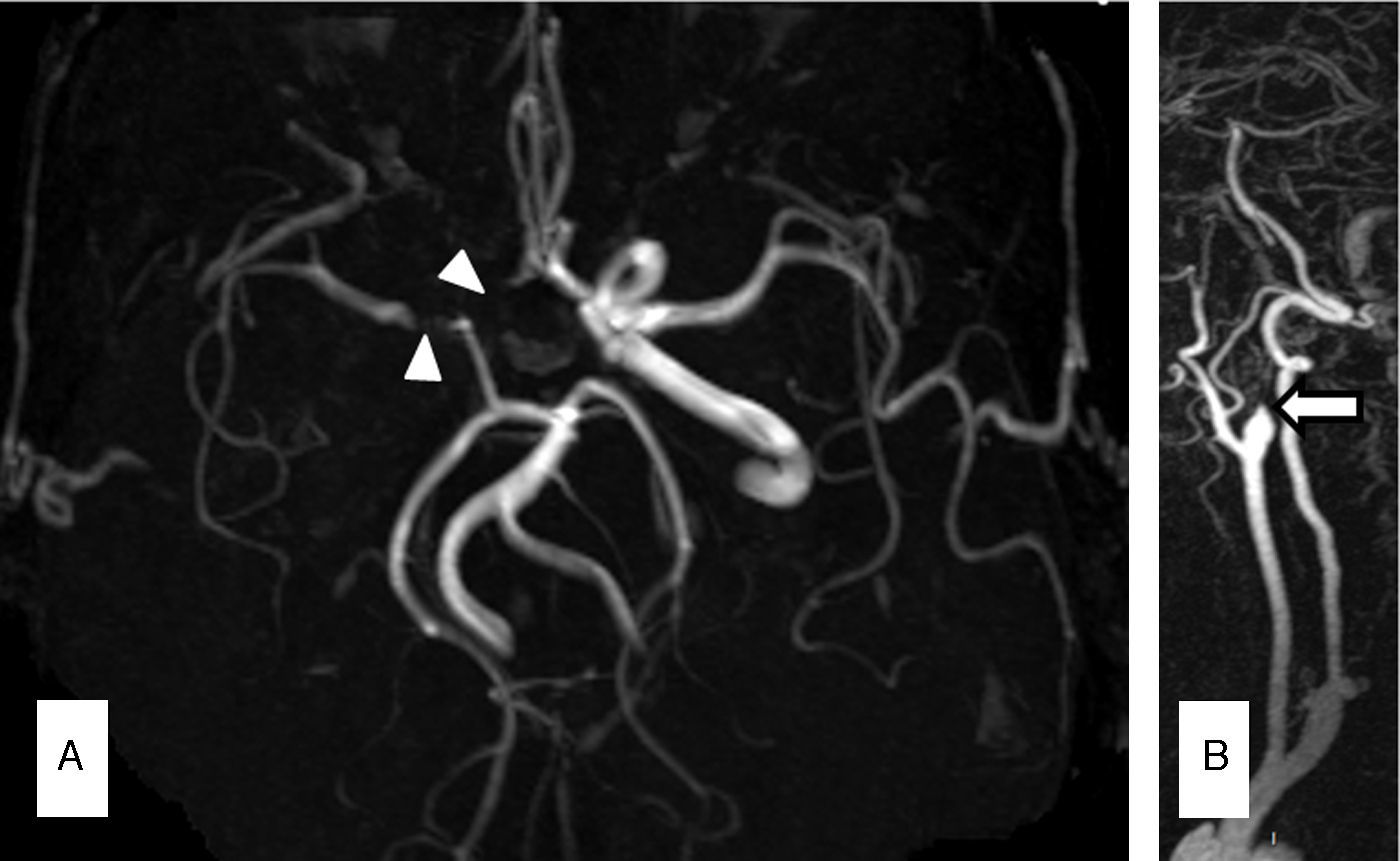

Case 3Our third patient was a 66-year-old man with a history of CML treated with nilotinib 300mg twice daily throughout the previous 7 years. The patient visited our department due to 2 transient episodes of hemiparesis and left hemihypaesthesia. His 10-year ASCVD risk was 9.3%. An MRI scan revealed multiple ischaemic lesions in the right frontal and parietal cortex. MR angiography showed ICA dissection and MCA stenosis of more than 50% (Fig. 2A and B). After suspending treatment with nilotinib, we started treating the patient with lipid-lowering drugs and acenocoumarol as an anticoagulant agent. At 3 months, a follow-up CT angiography showed persistent ICA occlusion and we opted to replace acenocoumarol with aspirin.

DiscussionNilotinib has been proven to be an effective treatment for CML.8 Nevertheless, long-term follow-up studies have documented such vascular events as PAD, coronary artery disease, or cerebrovascular disease in a significant percentage of patients receiving this treatment.9,10 Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this association. The effects of nilotinib on nonhematopoietic cells, such as vascular and perivascular cells, mast cells, or pancreatic cells, might promote development of atherosclerosis, hyperglycaemia, or hypercholesterolaemia.2 Furthermore, the TKI ponatinib has been associated with vascular and cerebral events, which suggests a potential drug class effect.1,11 However, such events have not been described with imatinib or dantinib.

Two of our patients presented pronounced intracranial atherosclerosis. Similar findings have been described previously in patients treated with nilotinib4 and ponatinib.11 The third patient showed dissection of an extracranial large vessel, a manifestation of vascular involvement that had not previously been described in patients treated with nilotinib.

Some experts have suggested that estimating CVR using such validated scales as those developed by the AHA7 or the European Society of Cardiology12 may help identify patients with a higher risk of adverse vascular events.1,13

Clinicians should be aware of the association between nilotinib and cerebrovascular events and thus avoid that drug in patients with a high CVR, or else monitor the related metabolic changes that may appear, such as hypercholesterolaemia or hyperglycaemia. Likewise, we recommended informing patients treated with nilotinib about stroke symptoms so that they would know to seek medical attention promptly.

We would like to thank Dr Francisco Cervantes for his contributions.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Galván JB, Borrego S, Tovar N, Llull L. Nilotinib como factor de riesgo de ictus isquémico. A propósito de 3 casos. Neurología. 2017;32:411–413.