Interferon-β (IFN-β) is an immunomodulatory agent that has been used for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) for more than twenty years now. Its efficacy and tolerability are well known as well as its side effects.1 We present a case of a woman diagnosed of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) who developed two spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) while on subcutaneous IFN-β-1b and intramuscular IFN-β-1a.

A 56-year-old woman smoker of 10 cigarettes per day otherwise healthy, was diagnosed of RRMS in 2006 due to a left hemi-hypoesthesia relapse, three periventricular, two subcortical and an infratentorial lesion in a brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and positive IgG oligoclonal bands in cerebrospinal fluid. She had been treated with subcutaneous IFN-β-1b 250μg every two days for eight years. She suffered a new relapse (transverse myelitis) in 2009, with complete symptoms resolution. She was admitted to Emergency Department (ED) due to status epilepticus in February 2014. No prior history of head trauma was reported. A brain Computed Tomography (CT) showed a right frontal hematoma (24mm×28mm×32mm) (Fig. 1a). She was transferred to Intensive Care Unit where she needed orotracheal intubation, sedation and antiepileptic treatment.

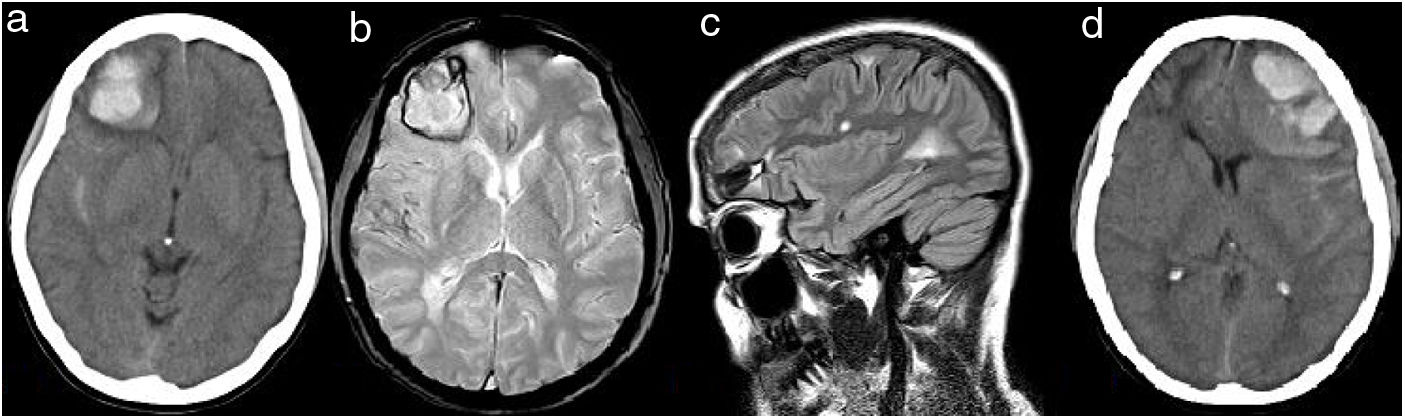

(a) CT brain (2014) showing right frontal hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage around temporal lobe. (b) Gradient Echo T2 sequence one month later showing hypointense signal around temporal lobe due to subarachnoid hemorrhage and around right frontal hemorrhage. No hypointense signals suggestive of microbleeds are showed. (c) High signal lesions on axial FLAIR-T2 sequence one month later showing juxtacortical and periventricular lesions suggestive of MS diagnosis. (d) CT brain (2019) showing left frontal hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage around frontal and temporal lobe, and mass effect.

Initial blood pressure was 127/72mmHg. Routine laboratory tests and drugs in urine were normal on admission. An extensive coagulopathy panel, including platelet count and function tests, coagulation times, and hemorrhagic diathesis was uninformative. Serologies were also negative. A cerebral angiography did not find any aneurysm, arterial or venous malformations. A brain MRI did not show any underlying vascular abnormality, signs of vasculitis, brain tumor or cerebral microbleeds one month later (Fig. 1b and c). Brain biopsy was not performed. The patient did not have any personal or familial history of spontaneous bleeding, nor during minor surgeries. She did not have history of cognitive impairment or other vascular risk factors apart from smoking. The patient recovered appropriately and no neurosurgical treatment was needed.

In August 2014, IFNβ was switched to subcutaneous glatiramer acetate (20mg/day) and then discontinued in November 2014 because of dermatological side effects. In December 2014, intramuscular IFN-β-1a (30μg per week) was started. By that time, the patient had been without disease activity and had a score of 2.5 in the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Follow up MRI (2016 and 2018) did not find disease activity, nor found them any cerebral microbleeds.

In April 2019, she suffered a new left motor and sensitive relapse. Blood and urine analysis did not find any abnormality and urgent CT did not show any new finding. She was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 1g daily for five days. The day after finishing this treatment, she was admitted to ED complaining of headache and somnolence. Blood pressure was 150/90mmHg. Brain CT showed a left frontal intracerebral hemorrhage with mass effect (Fig. 1d) without contrast enhancement or venous thrombosis signs. Urgent left frontal craniotomy was performed. An extensive investigation for coagulopathy was repeated, but it was unnoticeable again.

In January 2020, EDSS score was 3.5 (right pyramidal signs, right leg weakness and left hemi-hypoesthesia). An extensive neuropsychological study found mild amnesic cognitive impairment and low quality of life assessment. Since the patient suffered two spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhages while on interferon-β therapy without any other potential cause, we might consider the possible relationship between interferon-β and recurrent ICHs in this patient.

Interferon-β is a natural cytokine secreted in response to pathogens and other substances. It is claimed that it has immunomodulatory, antiviral, antitumoral and anti-inflammatory effects.2 It exerts them via different mechanisms such as the prevention of migration of leukocytes across the blood-brain-barrier or by modifying antigen presentation,3 but it has also effects on endothelial cells as shown in cancer or during viral infections.4

ICHs in MS patients are uncommon, may occur generally in patients with previous vascular risk factors. Moreover, patients under disease modifying therapy might have a trend against ICH.5 A review of the literature found only two cases similar to our patient: two women on interferon-β-1b for MS. One of them, like ours, suffered an ICH while on treatment with methylprednisolone for a MS relapse,6 and the other, suffered two spontaneous and bilateral ICHs within four days7 without concomitant corticosteroid therapy, as first ICH suffered by our patient. It is noticeable that interferon-β has been linked to thrombotic microangiopathy, Raynaud Phenomenon or pulmonary arterial hypertension, suggesting a procoagulant and vasoconstrictive effect, probably related to an impairment in endothelial cell functions, as shown in vitro.8,9 There are also reports of severe bleedings in other organs in patients under interferon-β therapy10,11 and of an increase in cardiovascular risk.12

In the case we present, common factors for ICH, except smoking, were absent and ICH common and uncommon causes were also ruled out. It has been recently shown that patients with MS have a higher risk of hemorrhagic stroke compared to non-MS population, specially within the first five years after MS diagnosis.13 Exposure to a specific MS treatment was not considered in that meta-analysis. Since it is strikingly rare that two spontaneous ICHs occur in the same patient in the absence of an underlying disorder, we cannot preclude a potential relation to Interferon- β in our patient's context. If a patient with MS under Interferon-β therapy suffers a hemorrhagic event and alternative causes are excluded, Interferon-β discontinuation might be considered. As far as we as concerned, this would be the third case published of ICH in a patient with MS under IFN-β treatment. More studies are warranted to evaluate the possible relationship between the drug and this severe complication.

FundingAuthors do not receive any funding for this paper.

Conflict of interestAuthors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose associated with this publication.