Patients’ knowledge about their medications is key to guarantee therapeutic compliance in chronic diseases.

Aims of the studyTo determine patients’ knowledge of oral preventive treatment (OPT) in migraine.

MethodsThis is a cross-sectional study evaluating knowledge of medication with a validated questionnaire that assessed: therapeutic objective, process of use, safety and conservation.

Results198 patients were included. Mean age was 45.4 ± 11.5 years-old and 92.4% were women. A 61.1% of migraine patients did not know the medication they used, 55.1% showed insufficient knowledge and 6.1% had no knowledge. The most known dimension was “conservation” (80.3%) and the most unknown dimension of was safety (33.7%). In this regard, 82.3% considered that they should not take precautions when taking the treatment, 80.3% stated that it had no contraindications and 82.8% were unaware of possible interactions with other medications. Worse knowledge about OPT was associated with longer time since migraine onset (p = .049), higher scores on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (p = .021), less qualified jobs (p = .045), use of monotherapy (p = .001) and longer periods since OPT initiation (p = .013).

ConclusionsThe majority of migraine patients did not adequately know their preventive treatment, despite identifying some of the items related to their medication. The present study shows that knowledge of patients about their preventive treatment should be evaluated in clinical practice and could help migraine patients in the correct use of OPT.

El conocimiento de los pacientes sobre su medicación es clave para garantizar el cumplimiento terapéutico en las enfermedades crónicas.

ObjetivoDeterminar el grado de conocimiento de los pacientes con migraña sobre su tratamiento preventivo oral (TPO).

MétodosEstudio transversal que evaluó el conocimiento de los pacientes sobre su medicación (CPM) mediante un cuestionario validado que valora cuatro dimensiones: objetivo terapéutico, proceso de uso, seguridad y conservación.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 198 pacientes: 92,4% mujeres, edad promedio 45,4 ± 11,5 años. El 61,1% desconocía la medicación que utilizaba para su migraña, de los que un 55,1% mostraba un conocimiento insuficiente y un 6,1% no tenía ningún conocimiento. La dimensión más conocida fue “conservación” (80,3%) y la menos conocida fue “seguridad” (33,7%). A este respecto, el 82,3% consideró que no debía tomar precauciones en la toma de su tratamiento, el 80,3% afirmó no conocer las posibles contraindicaciones y el 82,8% desconocía la existencia de interacciones con otros medicamentos. Un peor conocimiento global se asoció con puestos laborales menos cualificados (p = 0,045), un mayor tiempo desde el inicio de la migraña (p = 0,049), mayores periodos desde el inicio del TPO (p = 0,013), uso del fármaco en monoterapia (p = 0,001), y una mayor puntuación en la Escala de Ansiedad y Depresión Hospitalaria (p = 0,021).

ConclusionesPese a identificar algunos de los aspectos relacionados con su medicación, la mayoría de los pacientes con migraña no conocen adecuadamente su tratamiento preventivo. Por ello, el conocimiento sobre el TPO debería ser evaluado en la práctica clínica ya que podría ayudar a un uso correcto de su medicación.

Rates of adherence to therapies for chronic diseases are approximately 50% in developed countries.1 The World Health Organization considers poor treatment adherence a “worldwide problem of striking magnitude.” Different factors have been related to poor adherence to long-term therapy, including patients having insufficient knowledge of medication.2

Migraine is the main cause of years lived with disability between 15 and 49 years of age.3 However, unlike in other causes of neurological disability, prophylactic treatments may change the lives of patients with migraine and alleviate their disease burden.4 The most frequent options are oral preventive treatments (OPT), which are widely recommended in clinical practice guidelines.4 Unfortunately, long-term adherence to these therapies is poor, mainly due to suboptimal efficacy and tolerability. In Spain, the Persistence, use of resources and costs in patients under migraine preventive treatment (PERSEC) study has shown that approximately 70% of patients with migraine who start OPT discontinue treatment before 12 months.5

However, such a determinant factor for adherence as the degree of knowledge of medication has not previously been assessed in this disease. The main aim of our study is to assess these patients’ knowledge of their preventive therapies for migraine, and to identify the factors influencing the degree of patients’ knowledge of medication.

MethodsStudy design and participantsThis is a cross-sectional observational study including patients attended by a headache specialist at 10 external neurology consultations in Spain (March–August 2020). Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) diagnosis of migraine according to the criteria of the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3)6; and 2) stable treatment for at least 3 months with an OPT included in the guidelines of the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Headache Study Group7: propranolol, nadolol, atenolol, metropolol, nebivolol, topiramate, zonisamide, valproic acid, gabapentin, lamotrigine, candesartan, lisinopril, flunarizine, amitriptyline, and venlafaxine. We excluded patients aged below 18 years, with psychiatric comorbidities, and not willing to participate. The study was approved by the drug research ethics committee of Navarre (PI_2019/130).

Study variablesWe gathered data on demographic and clinical characteristics. We analysed the number of previous treatments, the type of treatment regime (monotherapy/polymedication), treatment duration, and the physician prescribing the OPT (headache specialist/general neurologist/emergency medicine physician/general practitioner). The impact of migraine was assessed using the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), and anxiety and depression with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

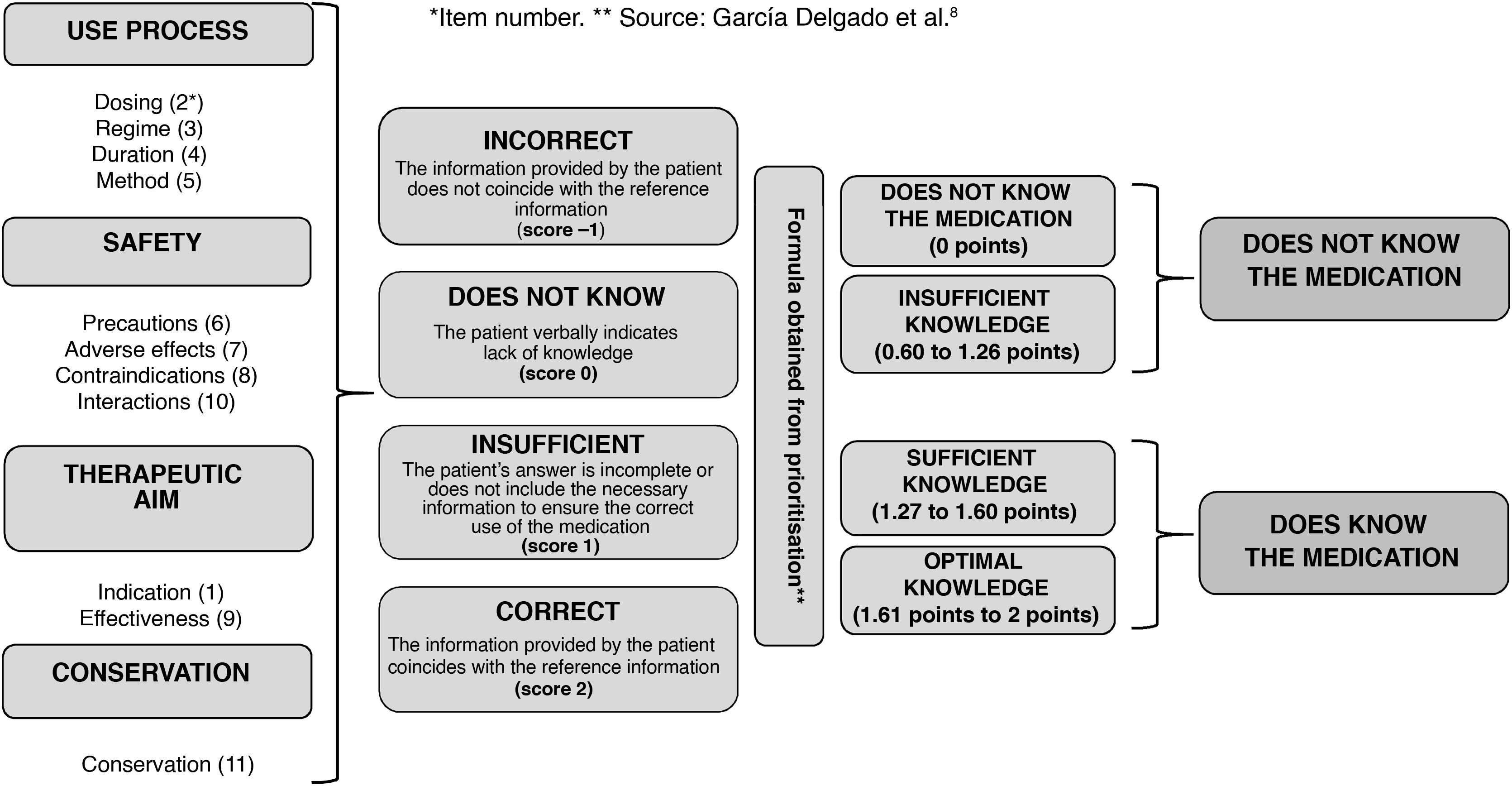

Evaluation of patients’ knowledge of medicationPatients’ knowledge of medication was assessed with the validated version of a questionnaire assessing the level of knowledge patients have about their medication,8 which includes 11 items assessing 4 dimensions: therapeutic aim, use process, safety, and conservation. Each item is scored differently depending on the dimension. The first 5 items (1-indication, 2-dosing, 3-regime, 4-treatment duration, and 5-administration) correspond to the minimum criteria for correct use of a medication.8,9 A score was assigned to each answer, depending on the degree of concordance between the data provided by the patient and the reference information. Subsequently, according to the algorithm of the original formula, knowledge was classified as: 1) knows the medication or 2) does not know the medication (Fig. 1). In those patients treated with several medications at the time of the evaluation, we selected one at random.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are expressed as percentages and frequencies. Continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR). Mean changes were analysed using the t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test, depending on whether data followed a normal distribution. We used the chi-square test for categorical variables and the comparison of frequencies. Statistical significance was established at P < .05. Statistical analysis was completed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS®) software, version 23.0.

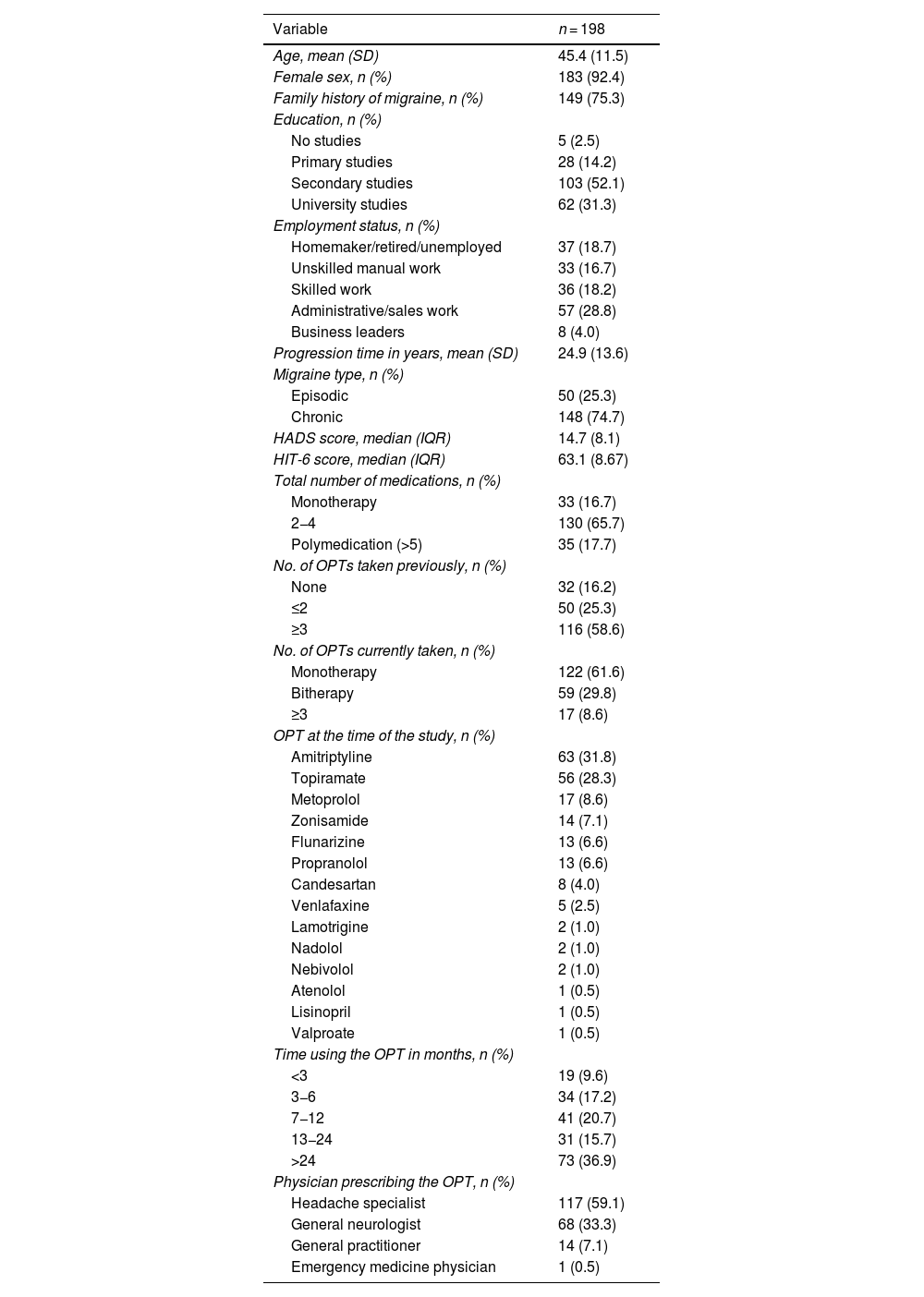

ResultsThe sample included 198 patients; 94.2% were women and the mean age (SD) was 45.4 years (11.5). Most patients had completed secondary education, and a significant percentage (31.3%) had university studies. Of all patients, 74.7% met criteria for chronic migraine (CM) and 75.3% had family history of migraine. Most patients (78.3%) presented severe migraine impact according to the HIT-6 score, with a median (IQR) of 63.1 (8.67) points. Regarding their OPT, 62.6% were receiving monotherapy and 58.6% had previously received ≥ 3 preventive treatments. At the time of the assessment, the most frequent OPTs were amitriptyline (31.8%), topiramate (28.3%), and zonisamide (7.1%). Treatment had been prescribed by a headache specialist in 59.1% of cases. Demographic and clinical variables are detailed in Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and treatment variables.

| Variable | n = 198 |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 45.4 (11.5) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 183 (92.4) |

| Family history of migraine, n (%) | 149 (75.3) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| No studies | 5 (2.5) |

| Primary studies | 28 (14.2) |

| Secondary studies | 103 (52.1) |

| University studies | 62 (31.3) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Homemaker/retired/unemployed | 37 (18.7) |

| Unskilled manual work | 33 (16.7) |

| Skilled work | 36 (18.2) |

| Administrative/sales work | 57 (28.8) |

| Business leaders | 8 (4.0) |

| Progression time in years, mean (SD) | 24.9 (13.6) |

| Migraine type, n (%) | |

| Episodic | 50 (25.3) |

| Chronic | 148 (74.7) |

| HADS score, median (IQR) | 14.7 (8.1) |

| HIT-6 score, median (IQR) | 63.1 (8.67) |

| Total number of medications, n (%) | |

| Monotherapy | 33 (16.7) |

| 2−4 | 130 (65.7) |

| Polymedication (>5) | 35 (17.7) |

| No. of OPTs taken previously, n (%) | |

| None | 32 (16.2) |

| ≤2 | 50 (25.3) |

| ≥3 | 116 (58.6) |

| No. of OPTs currently taken, n (%) | |

| Monotherapy | 122 (61.6) |

| Bitherapy | 59 (29.8) |

| ≥3 | 17 (8.6) |

| OPT at the time of the study, n (%) | |

| Amitriptyline | 63 (31.8) |

| Topiramate | 56 (28.3) |

| Metoprolol | 17 (8.6) |

| Zonisamide | 14 (7.1) |

| Flunarizine | 13 (6.6) |

| Propranolol | 13 (6.6) |

| Candesartan | 8 (4.0) |

| Venlafaxine | 5 (2.5) |

| Lamotrigine | 2 (1.0) |

| Nadolol | 2 (1.0) |

| Nebivolol | 2 (1.0) |

| Atenolol | 1 (0.5) |

| Lisinopril | 1 (0.5) |

| Valproate | 1 (0.5) |

| Time using the OPT in months, n (%) | |

| <3 | 19 (9.6) |

| 3−6 | 34 (17.2) |

| 7−12 | 41 (20.7) |

| 13−24 | 31 (15.7) |

| >24 | 73 (36.9) |

| Physician prescribing the OPT, n (%) | |

| Headache specialist | 117 (59.1) |

| General neurologist | 68 (33.3) |

| General practitioner | 14 (7.1) |

| Emergency medicine physician | 1 (0.5) |

HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HIT-6: Headache Impact Test; OPT: oral preventive treatment; SD: standard deviation.

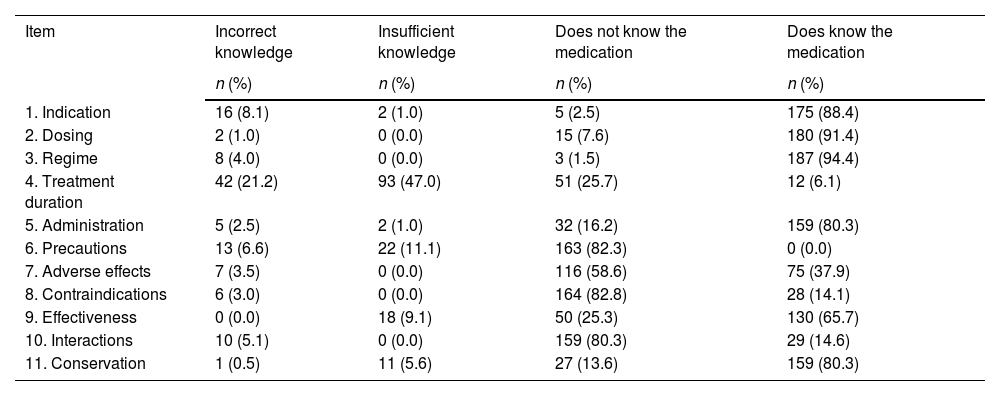

According to the data obtained in the questionnaire, 61.1% of patients with migraine did not know the medication they were using, with 55.1% of them showing insufficient knowledge and 6.1% no knowledge at all. Assessment of the different dimensions showed that the most widely known was conservation (80.3%) and the least known was safety (33.7%). In this regard, 82.3% considered that no precautions should be taken regarding their OPT, and 58.6% were not able to identify any adverse effect (AE) associated with their medication. Furthermore, 80.3% asserted that their OPT had no contraindications and 82.8% did not know of any possible interactions with other medications. Table 2 shows the frequency of the different responses to each item.

Frequency of each response for items on the questionnaire assessing patients’ knowledge of their medication.

| Item | Incorrect knowledge | Insufficient knowledge | Does not know the medication | Does know the medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| 1. Indication | 16 (8.1) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.5) | 175 (88.4) |

| 2. Dosing | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (7.6) | 180 (91.4) |

| 3. Regime | 8 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.5) | 187 (94.4) |

| 4. Treatment duration | 42 (21.2) | 93 (47.0) | 51 (25.7) | 12 (6.1) |

| 5. Administration | 5 (2.5) | 2 (1.0) | 32 (16.2) | 159 (80.3) |

| 6. Precautions | 13 (6.6) | 22 (11.1) | 163 (82.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| 7. Adverse effects | 7 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 116 (58.6) | 75 (37.9) |

| 8. Contraindications | 6 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 164 (82.8) | 28 (14.1) |

| 9. Effectiveness | 0 (0.0) | 18 (9.1) | 50 (25.3) | 130 (65.7) |

| 10. Interactions | 10 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 159 (80.3) | 29 (14.6) |

| 11. Conservation | 1 (0.5) | 11 (5.6) | 27 (13.6) | 159 (80.3) |

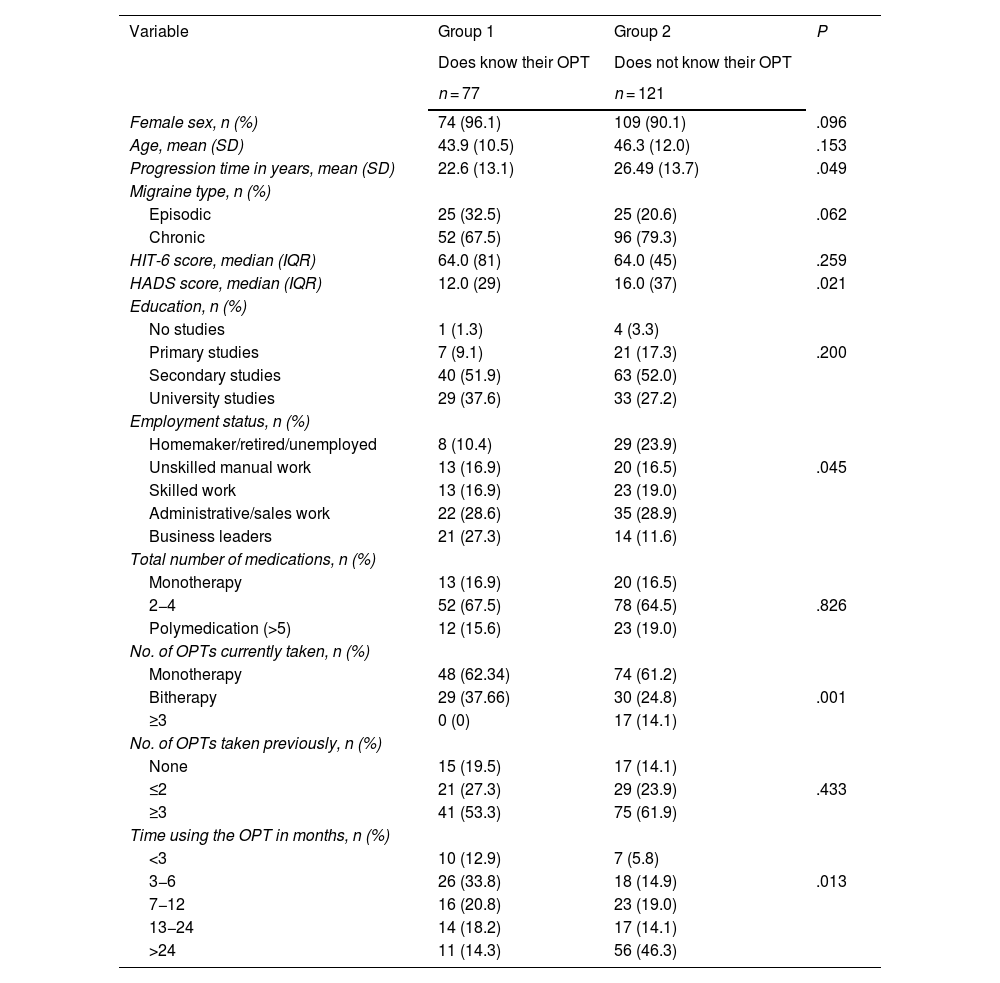

Lack of knowledge of the OPT was associated with longer disease duration (P = .049), higher HADS scores (P = .021), and less qualified work (P = .045). Patients receiving monotherapy (P = .001) and those with longer times since the onset of therapy (P = .013) had lower rates of knowledge of their medication. These results are summarised in Table 3.

Differences in knowledge of oral preventive treatment depending on baseline characteristics.

| Variable | Group 1 | Group 2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Does know their OPT | Does not know their OPT | ||

| n = 77 | n = 121 | ||

| Female sex, n (%) | 74 (96.1) | 109 (90.1) | .096 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 43.9 (10.5) | 46.3 (12.0) | .153 |

| Progression time in years, mean (SD) | 22.6 (13.1) | 26.49 (13.7) | .049 |

| Migraine type, n (%) | |||

| Episodic | 25 (32.5) | 25 (20.6) | .062 |

| Chronic | 52 (67.5) | 96 (79.3) | |

| HIT-6 score, median (IQR) | 64.0 (81) | 64.0 (45) | .259 |

| HADS score, median (IQR) | 12.0 (29) | 16.0 (37) | .021 |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| No studies | 1 (1.3) | 4 (3.3) | |

| Primary studies | 7 (9.1) | 21 (17.3) | .200 |

| Secondary studies | 40 (51.9) | 63 (52.0) | |

| University studies | 29 (37.6) | 33 (27.2) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| Homemaker/retired/unemployed | 8 (10.4) | 29 (23.9) | |

| Unskilled manual work | 13 (16.9) | 20 (16.5) | .045 |

| Skilled work | 13 (16.9) | 23 (19.0) | |

| Administrative/sales work | 22 (28.6) | 35 (28.9) | |

| Business leaders | 21 (27.3) | 14 (11.6) | |

| Total number of medications, n (%) | |||

| Monotherapy | 13 (16.9) | 20 (16.5) | |

| 2−4 | 52 (67.5) | 78 (64.5) | .826 |

| Polymedication (>5) | 12 (15.6) | 23 (19.0) | |

| No. of OPTs currently taken, n (%) | |||

| Monotherapy | 48 (62.34) | 74 (61.2) | |

| Bitherapy | 29 (37.66) | 30 (24.8) | .001 |

| ≥3 | 0 (0) | 17 (14.1) | |

| No. of OPTs taken previously, n (%) | |||

| None | 15 (19.5) | 17 (14.1) | |

| ≤2 | 21 (27.3) | 29 (23.9) | .433 |

| ≥3 | 41 (53.3) | 75 (61.9) | |

| Time using the OPT in months, n (%) | |||

| <3 | 10 (12.9) | 7 (5.8) | |

| 3−6 | 26 (33.8) | 18 (14.9) | .013 |

| 7−12 | 16 (20.8) | 23 (19.0) | |

| 13−24 | 14 (18.2) | 17 (14.1) | |

| >24 | 11 (14.3) | 56 (46.3) |

HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HIT-6: Headache Impact Test; OPT: oral preventive treatment; SD: standard deviation.

Our study assesses the degree of knowledge of patients with migraine of their OPT. The main finding is that more than half of the patients showed insufficient knowledge of their OPT. In this regard, patients’ knowledge of their medication was assessed in different chronic diseases, with rates of knowledge between 17% and 29.4%; this percentage is higher when validated questionnaires are used.10,11

Though migraine is one of the leading causes of years lived with disability, the lack of knowledge and awareness of the disease is real. Viana et al.12 used a structured interview to assess knowledge of migraine in different countries worldwide, evidencing a lack of awareness of the disease among patients and professionals. However, such other crucial aspects as knowledge of symptomatic and preventive treatments for migraine have not been assessed to date.

In this regard, data from our study show that only 38.9% of participants obtained scores indicating adequate overall knowledge of their OPT. The rate of correct answers was higher when the degree of knowledge was evaluated according to the different dimensions; however, the contribution of each dimension to the original formula differs.8,11 Of the patients with migraine, 61.1% did not know the minimum criteria (1-indication, 2-dosing, 3-regime, 4-treatment duration, and 5-administration)for ensuring correct use of the drug.

The lowest percentage of knowledge was obtained for the dimension “safety”: AE (37.9%), contraindications (14.6%), interactions (14.1%), and precautions (11.1%). These data coincide with those reported in previous studies, in which only 16% of the patients frequently knew the AE of the drugs they were using and 19% knew the precautions to be taken when using them.13 AE are frequent in the majority of drugs used for migraine prevention, and therefore it is essential to explain to patients these possible events and how to manage them,4,7 as the lack of this awareness leads to treatment non-adherence and discontinuation.13

In contrast, the greatest levels of knowledge were observed in the dimensions therapeutic aim and use process, with percentages above 80%; this is consistent with other studies conducted in our setting.10 The highest percentages were observed for the degree of knowledge of the administration regime, probably because it involves a direct action on the patients’ part, and indication, in which a percentage similar to the 78% observed in other studies was obtained.14 The higher percentages observed in our results may be related to the patient sample (young patients with a chronic and disabling disease), as knowledge of medication is poorer, for example, among hospitalised elderly patients.13 The item with the lowest degree of knowledge in the dimension “use process” was treatment duration, as only 6.1% of patients were aware that the estimated duration ranges from 3 to 12 months. In this regard, different clinical practice manuals recommend maintaining OPT from 6 to 12 months4,7; however, treatment periods are established on an individual basis, according to severity, effectiveness, and tolerability.

Finally, we assess factors influencing the degree of knowledge; some authors describe an association between education level and patients’ knowledge of their medication, with poorer rates of knowledge among patients with lower education levels.9 In our study, we observed a lower degree of knowledge of the OPT in unemployed patients and in those with unskilled manual jobs, whereas executives and business leaders obtained higher scores. Such other sociodemographic variables as age or sex did not significantly influence the degree of knowledge of the treatment; in this regard, and considering that more than 90% of the patients in our study are women, we would underscore the relevance of assessing the degree of knowledge of preventive medication during pregnancy and breastfeeding, due to the possible implications for treatment adherence and the optimal management of their migraine.15

Furthermore, the degree of knowledge was poorer in patients with longer progression times of migraine; this coincides with results reported in other chronic diseases9; in turn, patients with CM scored lower than patients with episodic migraine. We also analysed the relevance of anxiety and depression in patients’ knowledge of their medication: patients with higher HADS scores presented more difficulties knowing their OPT. This is an important consideration, as psychiatric comorbidities may significantly impact treatment adherence in migraine.12,16

To conclude, we observed a significant association between treatment time and overall knowledge, with poorer knowledge of medications among patients with longer treatment times, especially in those with more than 24 months of treatment. This contrasts with the results of Delgado et al.,8 who observed a lower degree of knowledge in patients using the medication for over one year but less than 2 years. Similarly, a lower degree of knowledge was observed in patients with higher numbers of concomitant treatments; similar results are reported in previous studies.17

Our study has significant limitations. Firstly, we included all consecutive patients and assessed their prophylactic treatment at the time of the interview; this may involve a recall bias. However, patients are periodically assessed by a headache specialist, who would provide the necessary information on OPT. Secondly, some OPTs were prescribed by a physician other than their regular doctor; therefore, it is difficult to determine whether these low rates of knowledge of medication may be due to differences in the information provided by the different healthcare professionals. Lastly, the limited sample size makes it difficult to observe statistically significant differences and, therefore, to extrapolate our results.

In conclusion, our results show that the majority of patients with migraine have insufficient knowledge of their preventive treatments. Despite identifying some specific aspects, correct use of the treatment may not be guaranteed due to a lack of general knowledge. Therefore, we consider it necessary to assess knowledge in headache clinics and units, and thus be able to help patients to understand the correct process for using the medication. Accordingly, we encourage researchers to perform future studies to assess whether the degree of knowledge of preventive medication may be related to low rates of treatment adherence and persistence.

FundingThis study has received no private or public funding of any kind.