Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a serious global health problem that is ranked third among the leading causes of death worldwide. However, underdiagnosis remains common, especially in Spain. The CARABELA-COPD initiative aims to address these issues by optimizing processes across the diverse healthcare settings in Spain.

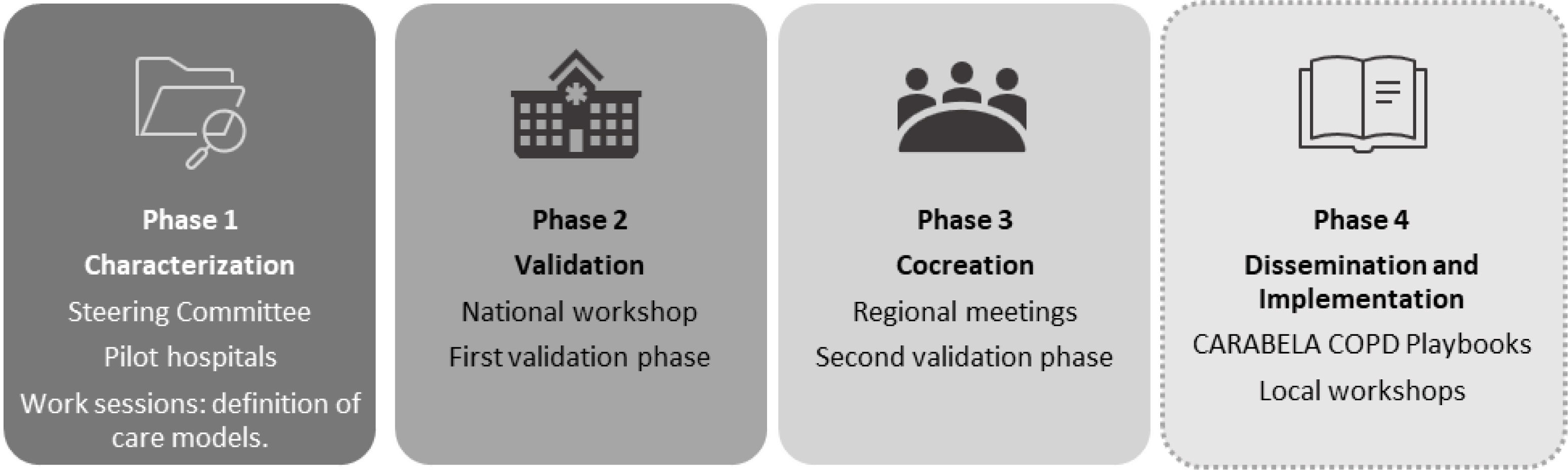

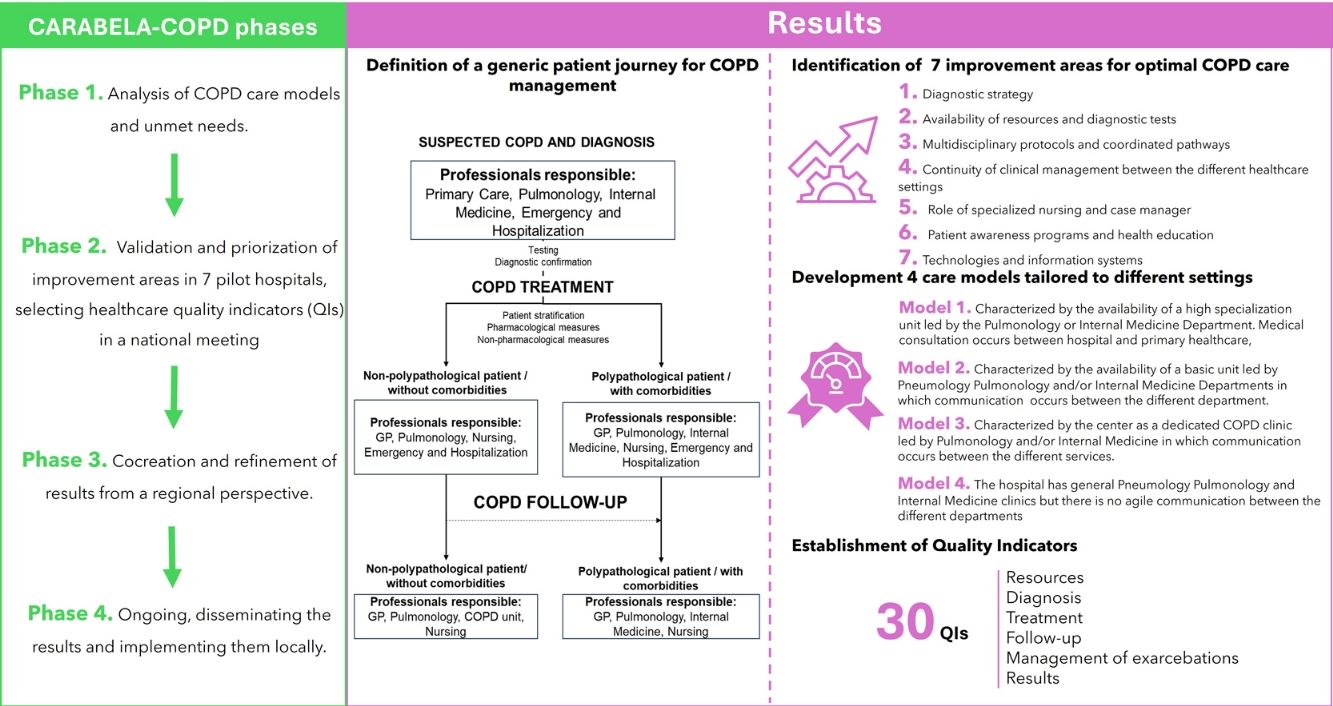

Material and methodsCARABELA-COPD employs lean methodology and fosters partnership between scientific societies, industry, clinicians, and managers to improve COPD care. The methodology consists of 4 phases: Phase 1 involved experts analyzing COPD care models and unmet needs; Phase 2, validation and priorization of improvement areas in 7 pilot hospitals, selecting healthcare quality indicators (QIs) in a national meeting; Phase 3, cocreation and refinement of results from a regional perspective; and Phase 4 is ongoing, disseminating the results and implementing them locally.

ResultsInitial phases of the initiative have defined a generic patient journey for COPD management from a multidisciplinary approach, identified 7 improvement areas for optimal COPD care, developed 4 care models tailored to different settings, and established QIs that have been validated in national and regional meetings.

DiscussionCARABELA-COPD is a novel practical approach to COPD management in Spain that acts as catalyst for a system transformation to boost overall system efficiency and enhance patient outcomes. It provides a clear framework for improvement, emphasizing interdisciplinary collaboration and communication. The ongoing implementation phase will require flexibility and constant evaluation to further enhance COPD care, ultimately improving patient quality of life and healthcare effectiveness.

La enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) es un problema de salud global grave y se sitúa como la tercera causa de muerte en todo el mundo. Sin embargo, su infradiagnóstico sigue siendo común, especialmente en España. La iniciativa CARABELA-EPOC tiene como objetivo abordar estos problemas mediante la optimización de los procesos asistenciales en los diversos entornos sanitarios en España.

Material y métodosCARABELA-EPOC emplea una metodología estructurada y eficiente que fomenta la colaboración entre sociedades científicas, industria, clínicos y gestores para mejorar la atención de las personas con EPOC. La metodología consta de cuatro fases: la fase 1 involucró a expertos que analizaron los modelos de atención en EPOC y las necesidades no cubiertas; la fase 2, implicó la validación y la priorización de áreas de mejora en siete hospitales piloto, seleccionando indicadores de calidad asistencial (IC) en una reunión nacional; la fase 3, co-creación y refinamiento de resultados desde una perspectiva regional, y la fase 4 está en curso, difundiendo los resultados e implementándolos a nivel local.

ResultadosLas fases iniciales de la iniciativa han definido un recorrido genérico del paciente para el manejo de la EPOC desde un enfoque multidisciplinar, han identificado 7 áreas de mejora para una atención óptima de la EPOC, han desarrollado 4 modelos de atención adaptados a diferentes entornos, y han establecido IC que han sido validados en reuniones nacionales y regionales.

DiscusiónLa iniciativa CARABELA-EPOC representa un enfoque innovador en la gestión de la EPOC en España, actuando como un catalizador para la transformación del sistema de salud, con el objetivo de incrementar su eficiencia y mejorar los resultados para los pacientes. Este proyecto proporciona un marco claro para la mejora continua, destacando la importancia de la colaboración y la comunicación interdisciplinarias. La fase de implementación, actualmente en curso, exigirá flexibilidad y una evaluación constante para seguir optimizando la atención de la EPOC, lo que finalmente se traducirá en una mejor calidad de vida para los pacientes y una mayor efectividad en la atención sanitaria.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, preventable, and treatable chronic lung disease that affects men and women worldwide. It is globally the third leading cause of death.1 The underdiagnosis rate is significant, accounting for up to 70% of patients worldwide,2 but increasing in Spain to 75%.3 COPD has a prevalence of 33.9 cases per 1000 habitants among individuals ≥40 years of age in Spain,4 while the EPISCAN II study reported a prevalence of 11.8% in the general population, 14.6% in men and 9.4% in women.5 COPD mortality is 4 times higher in men than in women, and from 2001 to 2019 it fell by approximately 50% in men and 33% in women.4

Healthcare costs of COPD management in Spain are high, particularly after an exacerbation,6 and expenditure is even higher in the case of older patients, longer hospital stays, intensive care unit admission, and higher Charlson index.7 In view of the aging population, this is clearly a scenario in which optimization should be addressed. Indeed, this issue has been on the table for decades. The Spanish National Health System 2009 COPD Strategy, for instance, identified various shortcomings in healthcare organization and established objectives and recommendations for improving the entire healthcare model,8 while an update of this document in 2014 highlighted the poor level of implementation of the strategy9 and the disparity between guideline recommendations and clinical practice.10 Improvement of COPD management and results in Spain has always been a priority, but despite many efforts over the years, the impact in terms of tangible results is still insufficient.11–13

In this context, scientific societies in partnership with industry have designed a novel approach. CARABELA-COPD is a holistic multidisciplinary approach that seeks to reduce possible inefficiencies and existing clinical variability by optimizing the processes and quality of healthcare, taking into account the many realities and settings present in our healthcare system. This effort is part of the ongoing CARABELA initiatives14 that are characterized by a particular mindset and a methodology aimed primarily at assessing and understanding the improvement areas within the Spanish healthcare system in managing high-burden chronic diseases, such as COPD. Moreover, it aims and to act as catalyst for system transformation toward practical improvements. In line with our integrative philosophy, all procedures are led by healthcare professionals, managers, scientific societies, and other relevant stakeholders.

This article describes the results of an ambitious reengineering initiative aimed at modeling our healthcare services and patient pathways for COPD in Spain and setting quality standards designed by the nationwide working groups of the 3 collaborating scientific societies SEMI (Spanish Society of Internal Medicine), SEPAR (Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery) SECA (Spanish Society of Quality of Care), in partnership with AstraZeneca. These results may serve as a basis for assessment and a roadmap for transformation toward optimal COPD care within our healthcare model.

Material and methodsThe general methodology for the CARABELA approach, based on lean methodology applied to healthcare ecosystems,15 has been described elsewhere.14 Representatives of SECA, SEMI, SEPAR, AstraZeneca, and dozens of clinicians and managers experts in COPD collaborated in the various phases of CARABELA-COPD.

Approval from an Ethics Committee was not required for this study as it did not involve the recruitment of patients. The process of obtaining informed consent was not applicable for the same reason.

The specific details of the CARABELA-COPD program are summarized here. The initial phases of this project comprised 4 main objectives: (1) to establish the various healthcare models present in the Spanish system, delineating the available resources and patient pathways used in each setting; (2) to identify unmet needs in each of the models described; (3) to define the healthcare quality indicators (QIs) that should be met to achieve an integrated optimal model; (4) to obtain a set of general solutions that may direct the improvement areas toward optimal care (Fig. 1).

Phase 1A multidisciplinary steering committee (SC) was formed, consisting of experts from three major Spanish scientific societies: SEMI, SEPAR, and SECA. Four pulmonologists, 4 internists, and 1 healthcare manager highly experienced in COPD management, were officially appointed by the presidents of these scientific societies. AstraZeneca provided logistical and technical support without influencing clinical decisions.

In their preliminary meetings, the CARABELA SC analyzed the state of COPD care in Spain, identified unmet needs, and improvement areas by performing a targeted literature search of current clinical guidelines, position papers and other expert opinion documents, systematic literature reviews and metanalysis regarding the disease and its treatment. They also defined a generic patient journey for COPD based on the retrieved literature and an iterative feedback process over several rounds of discussion.

Seven pilot centers were chosen (Supplementary material) by the SC, following predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria: geographic variability across Spain, representation of different management models (e.g., tertiary, regional hospitals), centers recognized for their leadership in COPD management and with no conflicts of interest (i.e., centers where SC members were employed were excluded to avoid bias), strong multidisciplinary collaboration, high-impact project participation, and use of data and technology for decision-making. Each hospital assembled multidisciplinary teams, including pulmonologists, internists, cardiologists, general practitioners, pharmacists, emergency physicians, and nurses. These teams validated the generic model proposed by the SC, tailoring it to their specific resources and patient pathways in various working sessions and identified seven improvement areas to be addressed in any initiative aimed at optimal COPD management. Individual reports were issued, and the SC discussed the results and agreed on the solutions, the healthcare models and patient pathways and drafted QIs to be presented in the national workshop for cocreation and further discussion.

Phase 2A national workshop was held on March 8, 2022, with 96 multidisciplinary healthcare professionals involved in the management of COPD. The participants voted on the prioritization of key areas for improvement and the alignment with quality indicators (QIs) proposed by the SC.

Two votes were held: one to rank the importance of the seven improvement areas (1 being the highest priority and 7 the lowest), and a second to assess the alignment with the QIs (scored from 1 to 10, where 10 indicates the highest alignment).

Phase 3Four regional meetings were conducted across Spain (north, south, east, and west regions) with a total of 41 experts participating (Supplementary materials). These experts represented a broad spectrum of healthcare providers from both primary care and hospital settings, ensuring diverse perspectives and local realities were considered. A structured voting process was employed to gather feedback and validate the proposed models and action points. Six votes were conducted: (1) Evaluation of key areas for improvement in COPD management: Experts were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the identified areas for improvement in the COPD care model. A scale from 1 to 10 was used, where 10 represented the highest level of agreement and 1 the lowest. This provided insight into the consensus regarding the priority areas for intervention in COPD management. (2) Selection of the COPD management model most relevant to each center: Participants were asked to identify which of the four proposed COPD care models (differentiated by level of specialization and resource availability) best aligned with the structure and capabilities of their respective centers. This helped assess the feasibility of implementing the proposed models across different healthcare settings in Spain. (3) Evaluation of agreement with the proposed COPD management models: After selecting the most relevant model, participants rated their degree of agreement with the proposed models using the same 1–10 scale. This provided feedback on whether the proposed models accurately reflected the needs and realities of each region's healthcare system. (4) Prioritization of action points: Experts were asked to prioritize the top five action points that they considered most critical for improving COPD management in their region. A total of 100 points were distributed, with each of the five selected actions receiving 20 points. This exercise helped identify which solutions were deemed most impactful and should be prioritized for implementation. (5) Validation of the QIs: The participants also evaluated their agreement with the set of QIs presented by the SC, again using a scale of 1–10. This process ensured that the QIs were both relevant and applicable to the local context of each region. (6) Assessment of satisfaction with the regional meeting: At the end of each regional meeting, participants were asked to rate their overall satisfaction with the meeting and the discussions held, using a scale from 1 to 10. This feedback was used to gauge the effectiveness of the meetings and the level of engagement among participants.

The insights gained from the regional meetings were instrumental in refining the proposed COPD care models, action plans, and QIs, ensuring they were adaptable to the specific needs of different regions.

Phase 4This is an ongoing phase that consists of the dissemination and application of models, solutions and variables developed in the previous phases. CARABELA workshops are conducted upon request in individual healthcare centers across Spain. The objective of these workshops, led by the healthcare professionals attending COPD patients, is to perform a self-assessment according to the model that best applies to reality of that team, and ultimately design a pathway toward optimized management within their care model or to upgrade to a higher model, according to their needs, aspirations, and resources. As this phase is ongoing, a description of results is beyond the scope of the present manuscript. However, clinical outcome data will be collected and published in future studies.

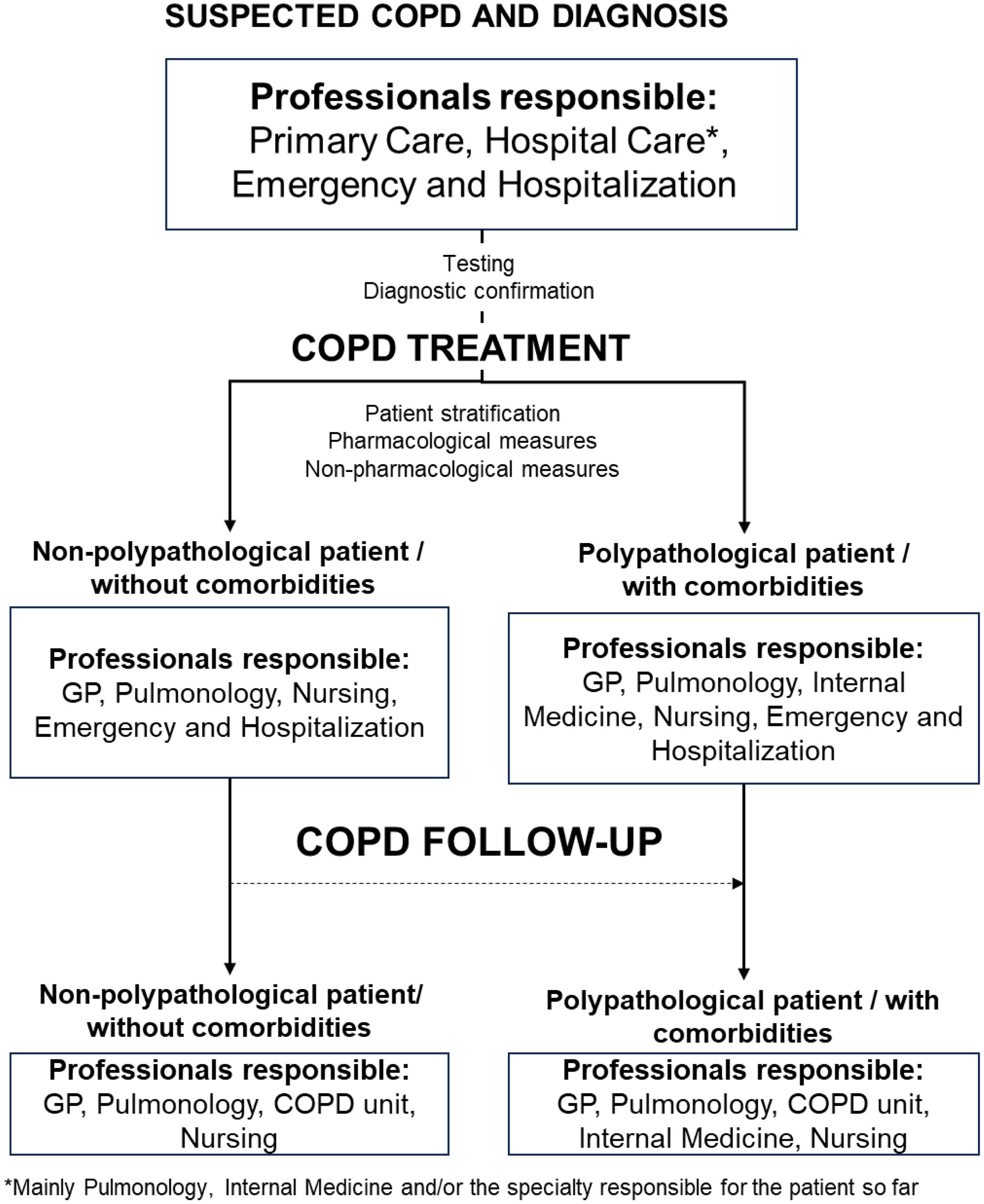

ResultsPhase 1. Characterization of COPD healthcare modelsIn the first instance, a general model for COPD management was discussed and defined by the SC. This model was based on a multidisciplinary approach and differentiated the patient circuit depending on the presence or absence of comorbidities (Fig. 2).

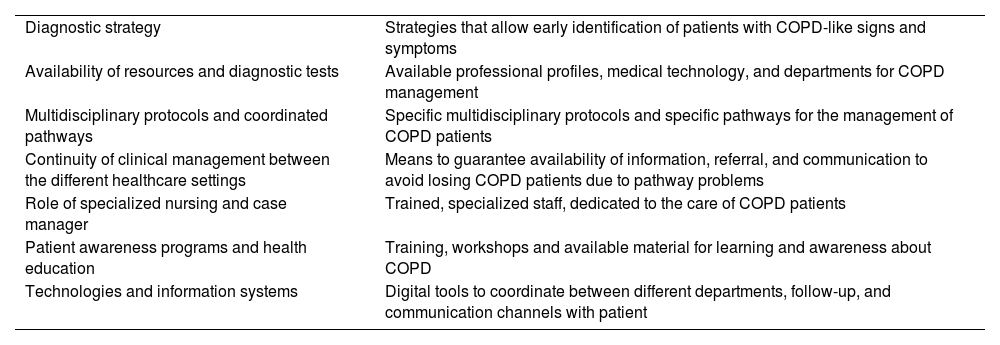

Individual sessions and detailed analyses of resources, protocols, and organization in the 7 pilot hospitals resulted in the identification of 7 improvement areas that should be addressed in any initiative aimed at optimal COPD management. These areas were recorded in reports and discussed with the SC (Table 1).

Improvement areas in COPD management identified at the pilot hospitals.

| Diagnostic strategy | Strategies that allow early identification of patients with COPD-like signs and symptoms |

| Availability of resources and diagnostic tests | Available professional profiles, medical technology, and departments for COPD management |

| Multidisciplinary protocols and coordinated pathways | Specific multidisciplinary protocols and specific pathways for the management of COPD patients |

| Continuity of clinical management between the different healthcare settings | Means to guarantee availability of information, referral, and communication to avoid losing COPD patients due to pathway problems |

| Role of specialized nursing and case manager | Trained, specialized staff, dedicated to the care of COPD patients |

| Patient awareness programs and health education | Training, workshops and available material for learning and awareness about COPD |

| Technologies and information systems | Digital tools to coordinate between different departments, follow-up, and communication channels with patient |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Using the improvement areas as the framework for assessment, evaluation and study of the 7 pilot hospitals, the design of 4 COPD care models emerged, defined as paradigms in the national healthcare system. The most important differential feature was the availability of a specialized COPD unit. These models were refined and agreed upon by the SC.

Model 1. Characterized by the availability of a high specialization unit led by the Pulmonology or Internal Medicine Department. Medical consultation occurs between hospital and primary healthcare, and the infrastructure and functional tests required for COPD management are available.

Model 2. Characterized by the availability of a basic unit led by Pulmonology and/or Internal Medicine Departments in which communication occurs between the different departments. It lacks accreditation but the infrastructure and some functional tests for the management of COPD are available.

Model 3. Characterized by the center as a dedicated COPD clinic led by Pulmonology and/or Internal Medicine in which communication occurs between the different services. It lacks accreditation but has access to infrastructure and performs some functional tests required for the management of COPD. Waiting lists are long.

Model 4. The hospital has general Pulmonology and Internal Medicine clinics but there is no agile communication between the different departments. It has no specific infrastructure and performs some functional tests for the management of COPD. Waiting lists are long.

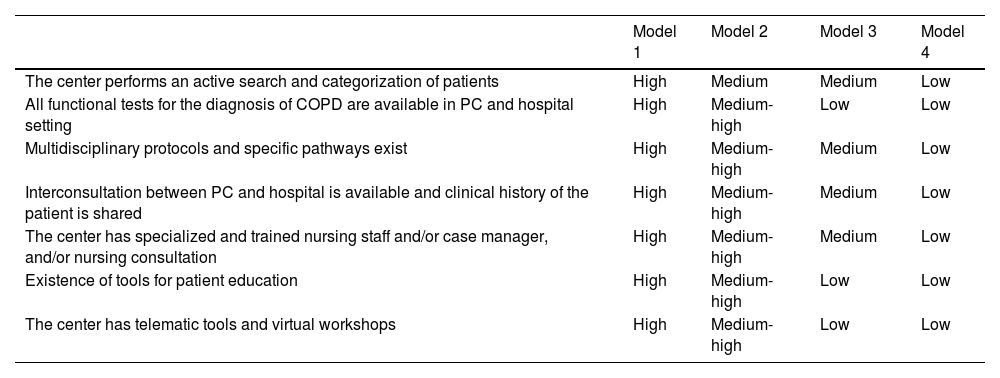

Details of each of these models have been drawn up in figures describing patient pathways for suspicion, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up (see Supplementary material). The degree of specialization of each model in different areas is summarized in Table 2.

Degree of specialization of the 4 models for COPD management.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The center performs an active search and categorization of patients | High | Medium | Medium | Low |

| All functional tests for the diagnosis of COPD are available in PC and hospital setting | High | Medium-high | Low | Low |

| Multidisciplinary protocols and specific pathways exist | High | Medium-high | Medium | Low |

| Interconsultation between PC and hospital is available and clinical history of the patient is shared | High | Medium-high | Medium | Low |

| The center has specialized and trained nursing staff and/or case manager, and/or nursing consultation | High | Medium-high | Medium | Low |

| Existence of tools for patient education | High | Medium-high | Low | Low |

| The center has telematic tools and virtual workshops | High | Medium-high | Low | Low |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PC, primary care setting.

The improvement areas and care models described in Phase 1, along with a list of QIs drafted by the SC, were discussed and voted on in a national meeting.

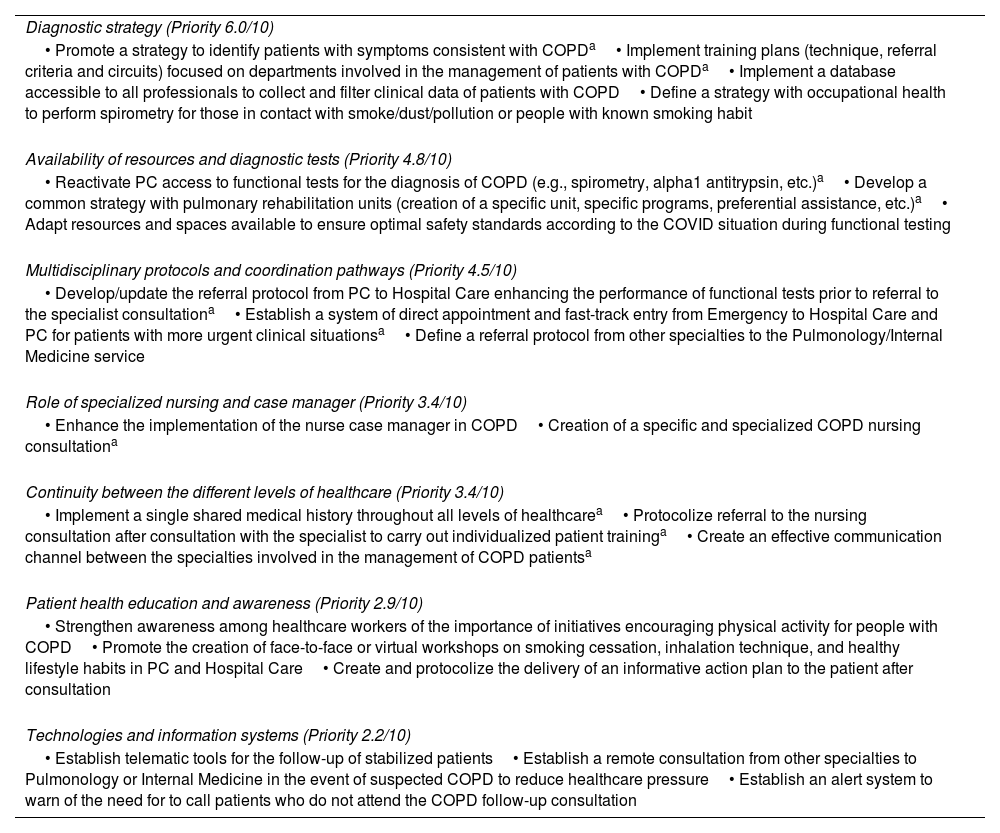

Priority of improvement areas for COPD managementParticipants in the national meeting voted on improvement areas and stablished priorities according to their importance or impact in the journey toward optimization of COPD management. Results are listed in Table 3.

List of solutions agreed in the national meeting to improve COPD management. Improvement area priority (bold) was voted in the phase 2 national meeting (10 being the highest priority).

| Diagnostic strategy (Priority 6.0/10) |

| • Promote a strategy to identify patients with symptoms consistent with COPDa• Implement training plans (technique, referral criteria and circuits) focused on departments involved in the management of patients with COPDa• Implement a database accessible to all professionals to collect and filter clinical data of patients with COPD• Define a strategy with occupational health to perform spirometry for those in contact with smoke/dust/pollution or people with known smoking habit |

| Availability of resources and diagnostic tests (Priority 4.8/10) |

| • Reactivate PC access to functional tests for the diagnosis of COPD (e.g., spirometry, alpha1 antitrypsin, etc.)a• Develop a common strategy with pulmonary rehabilitation units (creation of a specific unit, specific programs, preferential assistance, etc.)a• Adapt resources and spaces available to ensure optimal safety standards according to the COVID situation during functional testing |

| Multidisciplinary protocols and coordination pathways (Priority 4.5/10) |

| • Develop/update the referral protocol from PC to Hospital Care enhancing the performance of functional tests prior to referral to the specialist consultationa• Establish a system of direct appointment and fast-track entry from Emergency to Hospital Care and PC for patients with more urgent clinical situationsa• Define a referral protocol from other specialties to the Pulmonology/Internal Medicine service |

| Role of specialized nursing and case manager (Priority 3.4/10) |

| • Enhance the implementation of the nurse case manager in COPD• Creation of a specific and specialized COPD nursing consultationa |

| Continuity between the different levels of healthcare (Priority 3.4/10) |

| • Implement a single shared medical history throughout all levels of healthcarea• Protocolize referral to the nursing consultation after consultation with the specialist to carry out individualized patient traininga• Create an effective communication channel between the specialties involved in the management of COPD patientsa |

| Patient health education and awareness (Priority 2.9/10) |

| • Strengthen awareness among healthcare workers of the importance of initiatives encouraging physical activity for people with COPD• Promote the creation of face-to-face or virtual workshops on smoking cessation, inhalation technique, and healthy lifestyle habits in PC and Hospital Care• Create and protocolize the delivery of an informative action plan to the patient after consultation |

| Technologies and information systems (Priority 2.2/10) |

| • Establish telematic tools for the follow-up of stabilized patients• Establish a remote consultation from other specialties to Pulmonology or Internal Medicine in the event of suspected COPD to reduce healthcare pressure• Establish an alert system to warn of the need for to call patients who do not attend the COPD follow-up consultation |

Under these 7 improvement areas, 21 solutions that could be applied to all the identified models were defined. See summary in Table 3.

Participants discussed the approach to these action points and provided several practical insights. In terms of diagnostic strategy, the identification of multimorbid patients with suspected COPD, smokers with cough or dyspnea, and patients with other comorbidities should be established in a multidisciplinary manner. Mechanisms should also be implemented in hospitals to promote rapid access to functional tests for patients after their first consultation, to avoid competition with follow-up tests, since rapid diagnosis of the potential COPD patient is crucial. Once diagnosed, the second line, i.e., the availability of resources and diagnostic tests, comes into play.

The creation of networks of experts acting under a single care framework may be needed to make resources available. This would offer patients equal access to the most advanced technology needed for their management (new diagnostic techniques, gamified training, etc.). A shared resource structure between Hospital and Primary Care settings should be generated, and shared access to training resources and technology should also be available. This line also requires an increase in the number of respiratory rehabilitation consultations for patients with COPD and, finally, the creation or promotion of a multipurpose day hospital.

As for the implementation of protocols and pathways, protocols for integrated patient care throughout the healthcare process should be defined or updated and disseminated, while incorporating the vision of the different professionals and levels of healthcare involved throughout the process. Fast-track pathways and protocols for chronic patients should also be implemented.

The role of nursing staff and case managers was discussed. The professionals agreed that official specialized nursing programs should be promoted. Nursing consultations require physical space and the technology and equipment necessary for the follow-up and monitoring of patients. Finally, the figure of the professional case manager responsible for the intra/extra-hospital transitions of patients with COPD should be supported.

Continuity of healthcare in COPD is a must, so clinical follow-up protocols and the role and functions of nurses in patient monitoring and follow-up should be reinforced, as a reference for all professionals involved. Development/dissemination and the use of agile communication channels between the PC and hospital settings and among hospital departments should be implemented throughout the healthcare process. The role of a transversal coordinator with responsibilities and decision-making autonomy in all healthcare areas should be defined.

Educational programs for patients that adapt to their needs and their digital profile should be created. These programs should incorporate technological features that assist patients in learning about the management and self-management of their disease. This could include gamification tools, but the generation of valuable materials in physical format aimed at non-digital patients cannot be overlooked. Patient education programs in all settings and coordination of expert patient groups are crucial for patient empowerment, and the role of nursing in this aspect should be formalized.

Finally, in this age of technology and information systems, the current situation of informatics and technological options in healthcare centers must be examined. Innovative solutions may promote the creation of networks of experts who function under a single healthcare framework, offering patients equitable access to the latest technologies available in the care of their disease. The advantages and benefits of implementing groundbreaking technological tools should be exploited among the various disciplines. Computer systems should be employed to test the possible benefits of pilot technological tools, check barriers, and assess viability to decide on investment.

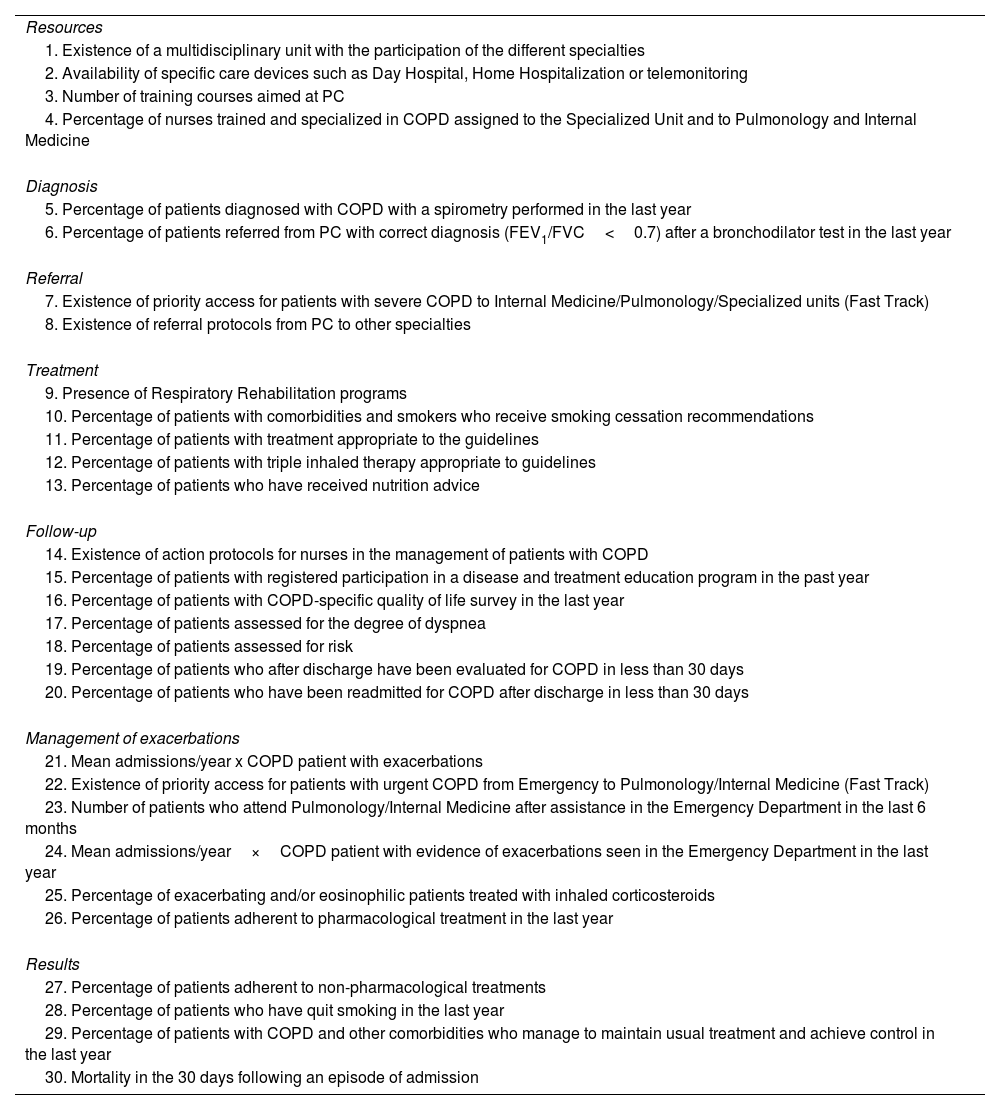

Healthcare quality indicatorsTable 4 contains the final list of QIs agreed upon in the national meeting and later validated in the regional meetings.

Healthcare quality indicators to assess the quality of COPD management.

| Resources |

| 1. Existence of a multidisciplinary unit with the participation of the different specialties |

| 2. Availability of specific care devices such as Day Hospital, Home Hospitalization or telemonitoring |

| 3. Number of training courses aimed at PC |

| 4. Percentage of nurses trained and specialized in COPD assigned to the Specialized Unit and to Pulmonology and Internal Medicine |

| Diagnosis |

| 5. Percentage of patients diagnosed with COPD with a spirometry performed in the last year |

| 6. Percentage of patients referred from PC with correct diagnosis (FEV1/FVC<0.7) after a bronchodilator test in the last year |

| Referral |

| 7. Existence of priority access for patients with severe COPD to Internal Medicine/Pulmonology/Specialized units (Fast Track) |

| 8. Existence of referral protocols from PC to other specialties |

| Treatment |

| 9. Presence of Respiratory Rehabilitation programs |

| 10. Percentage of patients with comorbidities and smokers who receive smoking cessation recommendations |

| 11. Percentage of patients with treatment appropriate to the guidelines |

| 12. Percentage of patients with triple inhaled therapy appropriate to guidelines |

| 13. Percentage of patients who have received nutrition advice |

| Follow-up |

| 14. Existence of action protocols for nurses in the management of patients with COPD |

| 15. Percentage of patients with registered participation in a disease and treatment education program in the past year |

| 16. Percentage of patients with COPD-specific quality of life survey in the last year |

| 17. Percentage of patients assessed for the degree of dyspnea |

| 18. Percentage of patients assessed for risk |

| 19. Percentage of patients who after discharge have been evaluated for COPD in less than 30 days |

| 20. Percentage of patients who have been readmitted for COPD after discharge in less than 30 days |

| Management of exacerbations |

| 21. Mean admissions/year x COPD patient with exacerbations |

| 22. Existence of priority access for patients with urgent COPD from Emergency to Pulmonology/Internal Medicine (Fast Track) |

| 23. Number of patients who attend Pulmonology/Internal Medicine after assistance in the Emergency Department in the last 6 months |

| 24. Mean admissions/year×COPD patient with evidence of exacerbations seen in the Emergency Department in the last year |

| 25. Percentage of exacerbating and/or eosinophilic patients treated with inhaled corticosteroids |

| 26. Percentage of patients adherent to pharmacological treatment in the last year |

| Results |

| 27. Percentage of patients adherent to non-pharmacological treatments |

| 28. Percentage of patients who have quit smoking in the last year |

| 29. Percentage of patients with COPD and other comorbidities who manage to maintain usual treatment and achieve control in the last year |

| 30. Mortality in the 30 days following an episode of admission |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1/FVC, ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1second to forced vital capacity; PC, primary care.

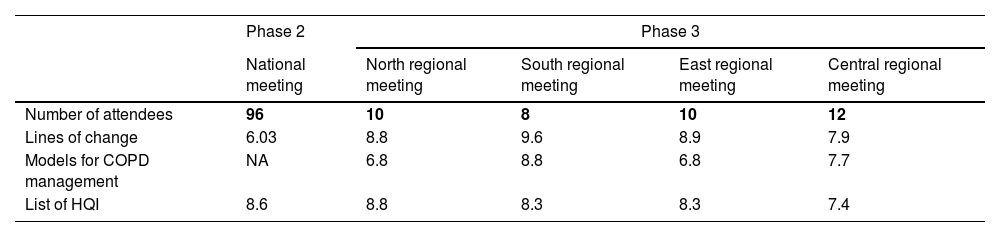

Regional meetings served as a forum to share and discuss the materials developed in previous phases and to measure the degree of agreement at a more granular level (Table 5). Priorities for solutions shown in Table 3 were also set, and a more in-depth discussion of potential actions adapted to the various realities was carried out. These discussions will be covered in another publication.

Summary of results obtained in the validation processes performed in the national and regional meetings of CARABELA-COPD. All items were scored from 0 to 10, 10 being the highest level of agreement.

| Phase 2 | Phase 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National meeting | North regional meeting | South regional meeting | East regional meeting | Central regional meeting | |

| Number of attendees | 96 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

| Lines of change | 6.03 | 8.8 | 9.6 | 8.9 | 7.9 |

| Models for COPD management | NA | 6.8 | 8.8 | 6.8 | 7.7 |

| List of HQI | 8.6 | 8.8 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 7.4 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NA, not applicable; HQI, Healthcare Quality Indicator.

This article summarizes the main results of 4 CARABELA-COPD phases. The CARABELA-COPD initiative generated a highly valuable set of insights on the realities, needs, aspirations, and vision of a considerable number of healthcare providers and managers treating COPD patients across Spain. The CARABELA mindset and methodology were applied to analyze the current organization and processes in detail, as a foundation for constructing a pathway toward optimal management in each setting. As a result, a comprehensive and integrated plan has been developed under the leadership of the collaborating scientific societies and industry partners to help healthcare teams and centers treating COPD in Spain systematically work toward aligning guidelines, recommendations, and national strategies.

A very important problem that healthcare teams face when treating COPD is the implementation of guidelines and optimal processes using the resources available in real life.10,16 Since the Spanish National Health System COPD Strategy was published in 2009,8 many national, regional and local efforts have been made, but the overall impact on the practical implementation of the many improvements that have been repeatedly recommended has been limited.9–13,17,18 Indeed, over the years, QIs and recommendations for the Spanish system have been developed for COPD,17,18 guidelines have been updated,1 solutions have been proposed,19 and official public plans have been issued, yet a recent discussion on the shortcomings in COPD management in Spain highlighted that, among other problems, the impact of public health plans was still ephemeral, coordination in healthcare settings was lacking, diagnostic issues existed, clinical practice guideline adherence was poor, and education of the population and patients was insufficient.20 Such opinions have been shared over the years one way or another by other voices.3,21,22

In such a scenario, we need to discuss which features would draw attention the CARABELA initiative in the field and how its results may add value to the therapeutic process. The first is the mindset itself: CARABELA was born as a collaborative framework in which all stakeholders in COPD management have a voice. One important factor of the many Spanish realities is diversity: diversity of healthcare centers and settings, profiles of healthcare professionals, resources, needs, and the patient population, all of which influence methods and organization. The 7 pilot centers were representative not only of the Spanish geography, but also of organizational models that had been created to respond to local necessities. These centers served as a basis to construct 4 models that could encompass all the requirements. The second feature is that all insights, proposals, and products are the result of a pragmatic approach to the realities of COPD care in Spain, and each professional profile of collaborating experts reported their real-world situation, along with their aspirational horizons. Hospital departments and units across Spain now use the resulting models and patient pathways in local workshops to recognize themselves and analyze their own organizational structure and processes, each setting an individual pathway for improvement. Thus, each care team can tailor its own plan for improving COPD care according to the QIs, solutions, and prioritized action points created for the implementation of optimal COPD management, aiming at their own viable goal, while continuing to address areas needing improvement. These improvement areas include underdiagnosis, healthcare system overload, high costs, chronicity, high prevalence, and the associated comorbidities that complicate the implementation of an integral, comprehensive, patient-focused healthcare model.

While the CARABELA-COPD initiative marks significant progress, it has some limitations. The applicability of its outcomes may vary across Spanish regions due to differences in healthcare settings and resources. Although we have attempted to ensure diverse representation through the selection of pilot hospitals and regional validation processes, the results obtained for the pilot centers may not fully capture all healthcare realities across the country. Moreover, the findings and models may need to be adjusted for use outside the Spanish public healthcare system. On the other hand, while the project successfully defined care models and identified key areas for improvement, clinical outcome data comparing the effectiveness of these models against traditional approaches have not yet been collected. This limitation arises because the initiative is still in Phase 4, which focuses on dissemination and local implementation. As such, the impact of the proposed care models on clinical outcomes will need to be evaluated in future studies. Another limitation concerns the involvement of specific healthcare professionals and institutions. Although the project included a broad range of professionals (pulmonologists, internists, primary care physicians, and nurses), it did not officially involve representatives from all relevant scientific societies which may have limited the scope of the recommendations. Nonetheless, the CARABELA-COPD mindset ensures that clear lines of work have been drawn and interdisciplinary collaboration has been greatly promoted, and the roles of many professionals in the management of COPD patients and the need for increasing communication among them in a collective pursuit have been highlighted.

During the implementation of all the insights and solutions developed in this manuscript, barriers will clearly need to be overcome in our continuous effort to improve. Addressing these areas will require a steady but flexible execution of the CARABELA-COPD blueprint, essential to ensure that the quality of healthcare is not strained and the QIs are met. Further investigation is warranted to respond to the new needs that will emerge during the transformation process, refining COPD management in Spain with the final goal of improving QoL in COPD patients and healthcare effectiveness.

FundingCARABELA-COPD is a co-organization accord between medical societies and AstraZeneca Spain.

Authors’ contributionsJavier de Miguel-Díez, Jesús Díez-Manglano, Inmaculada Mediavilla and Luciano Escudero participated in the conceptualization, drafting and writing of the manuscript. The final version of the manuscript has been reviewed and validated by all authors who participate in the CARABELA-COPD Scientific Committee.

Conflicts of interestInmaculada Mediavilla has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Boehringer-Ingelheim, MSD, Pfizer, and Bayer; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Novartis and Pfizer; she is the President of the Spanish Society for Quality of Care. Jesús Díez-Manglano has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Esteve, GSK, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. Javier de Miguel-Díez has received grants or contracts from GSK and AstraZeneca; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer, Chiesi, FAES, Ferrer, Gebro, GSK, Janssen, Menarini, Novartis, Roche, Teva and Pfizer; support for attending meetings and/or travel from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, FAES, Gebro, GSK, Menarini, Novartis, Roche, Teva, and Pfizer; he is the COPD coordinator of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery. Juan Luis García has received grants or contracts from GSK and AstraZeneca; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, GSK, Gebro, Sanofi, Grifols and Chiesi; support for attending meetings and/or travel from AstraZeneca, GSK and Sanofi; he has participated on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board from AstraZeneca and GSK he is the secretary of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery and the president of the Cantabrian Association for Respiratory System Research. Francisco Javier Medrano has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca. Francisco Casas-Maldonado has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, CSL Behring, Grifols and GSK; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and CSL Behring; support for attending meetings and/or travel from AstraZeneca, Boehringer- Ingelheim, and CSL Behring. Ramón Boixeda has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Gilead, and GSK; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Chiesi and Gilead; he has participated in a Data Safety Monitoring Board and Advisory Board for Bayer. María Belén Alonso-Ortíz has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Chiesi, FAES Farma, GSK and Nestlé Health Science and support for attending meetings and/or travel from Almirall, GSK and Novo Nordisk. Luciano Escudero, Carmen Corregidor, Eunice Fitas and Lucía Regadera are employees in AstraZeneca Medical Department. Sergio Campos has no conflicts of interest to report.

The authors acknowledge the participation of all the professionals participating in the regional meetings of the CARABELA-COPD initiative, and of all those involved in the pilot phase of the CARABELA-COPD initiative from Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro (Pontevedra, Spain), Hospital Clínico de Valencia (Valencia, Spain), Hospital Galdakao (Bizkaia, Spain), Hospital de Mieres (Asturias, Spain), Hospital La Paz (Madrid, Spain), Hospital El Bierzo (Ponferrada, Spain), Hospital Vall d’Hebron (Barcelona, Spain).

Medical writing support was provided under the guidance of the authors by Antoni Torres-Collado, PhD, Blanca Piedrafita, PhD and Vanessa Marfil, PhD from Medical Statistics Consulting (MSC), Valencia, Spain, and was funded by Astra Zeneca, Madrid, Spain, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

María Belén Alonso-Ortíz (Spanish Society of Internal Medicine), Ramón Boixeda (Spanish Society of Internal Medicine), Sergio Campos (Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery), Francisco Casas-Maldonado (Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery), Carmen Corregidor (AstraZeneca Farmacéutica Spain), Jesús Díez-Manglano (Spanish Society of Internal Medicine); Luciano Escudero (AstraZeneca Farmacéutica Spain), Eunice Fitas (AstraZeneca Farmacéutica Spain), Juan Luis García (Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery), Inmaculada Mediavilla (Spanish Society for Quality Care), Francisco Javier Medrano (Spanish Society of Internal Medicine), Javier de Miguel-Díez (Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery and Lucía Regadera (AstraZeneca Farmacéutica Spain).