Severe asthma management is associated with increased healthcare resource use. The CARABELA initiative employs lean methodology to optimize severe asthma management in Spain.

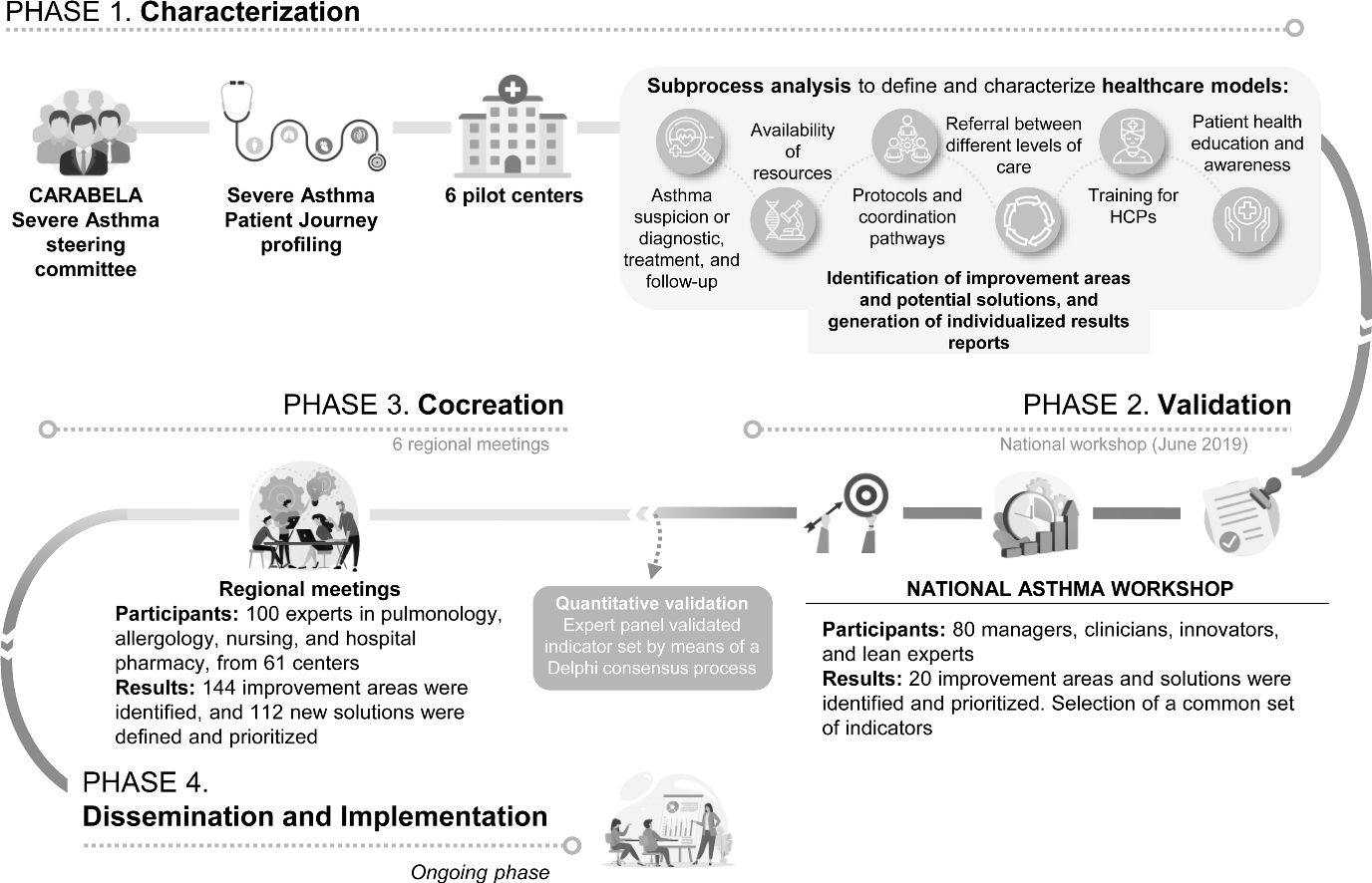

Material and methodsScientific Societies, clinicians, healthcare management and industry stakeholders implemented lean methodology to reorganize and optimize processes and design a practical, individualized approach to improve quality of care for the management of severe asthma patients. This initiative involved four phases: Phase 1 characterized severe asthma management models in six pilot hospitals, identifying improvement areas; Phase 2 validated and prioritized these areas and healthcare quality indicators in a National Workshop; Phase 3 focused on regional meetings to co-create and refine solutions; and Phase 4 is disseminating and implementing results locally by applying a digital tool and organizing tailored workshops.

ResultsThis CARABELA initiative identified 87 improvement areas, mainly in diagnosis and care coordination, and developed solutions emphasizing awareness, nursing roles, patient education, and communication. National and regional meetings produced 112 cocreated solutions and established healthcare quality indicators. Thirty-six hospitals are now implementing tailored improvement plans.

ConclusionsThe CARABELA-SA initiative revealed variability in severe asthma management across Spain, underscoring the need for standardized healthcare quality indicators. By engaging nearly 200 professionals, the initiative fostered collaboration and innovation and established a framework for ongoing improvement in managing severe asthma and other chronic diseases. The CARABELA initiative promotes patient-centered care and interdisciplinary collaboration with the objective of enhancing patient outcomes and healthcare efficiency.

El tratamiento del asma grave se asocia con un uso de recursos sanitarios creciente. La iniciativa CARABELA hace uso de la metodología Lean para optimizar el manejo del asma grave en España.

Material y métodosCon el trabajo conjunto de sociedades científicas, clínicos, gestores sanitarios y agentes de la industria se implementó la metodología Lean para reorganizar y optimizar los procesos asistenciales en el tratamiento del asma grave y diseñar un enfoque práctico e individualizado para mejorar la calidad asistencial de este manejo. Esta iniciativa se desarrolló en 4 fases: la fase 1 sirvió para caracterizar los modelos de gestión del asma grave en 6 hospitales piloto, con la identificación de áreas de mejora; en la fase 2 se validaron y priorizaron estas áreas e indicadores de calidad asistencial en una Reunión Nacional; la fase 3 se centró en reuniones regionales en las que se cocrearon y optimizaron distintas soluciones; y a través de la fase 4 se están difundiendo e implementando los resultados a nivel local mediante la aplicación de una herramienta digital y la organización de talleres ad hoc.

ResultadosEsta iniciativa CARABELA sirvió para identificar 87 áreas de mejora, sobre todo en el diagnóstico del asma grave y la coordinación de cuidados de los pacientes, y desarrollar soluciones enfocadas en la concienciación, el papel de enfermería, la educación al paciente y la comunicación. En las reuniones nacional y regionales se definieron 112 soluciones y se establecieron indicadores de calidad asistencial. Un total de 36 hospitales están aplicando planes de mejora específicos.

ConclusionesLa iniciativa CARABELA-AG puso de manifiesto la variabilidad en el manejo del asma grave en España, señalando la necesidad de estandarizar indicadores de calidad asistencial. Al involucrar a cerca de 200 profesionales, la iniciativa fomentó la colaboración y la innovación, y estableció un marco para la mejora continua en el tratamiento del asma grave y otras enfermedades crónicas. La iniciativa CARABELA promueve la atención centrada en el paciente y la colaboración interdisciplinar con el objetivo de mejorar el manejo de los pacientes y la eficiencia de la asistencia sanitaria.

Asthma is a syndrome that includes diverse clinical phenotypes that share similar clinical manifestations but different pathophysiological processes. Classically, it is defined as a chronic inflammatory disease of the respiratory tract, in which different cells and mediators of inflammation participate. It is conditioned in part by genetic factors and presents with bronchial hyperresponsiveness and variable airflow obstruction.1–3 Asthma affects approximately 8.5% of Spanish adults and approximately 10.5% of children.4,5

Clinical guidelines define severe asthma by the need for multiple drugs and high doses of inhaled corticosteroids, and this categorization is applicable to both controlled and uncontrolled asthma patients.1,2 Severe asthma is also associated with higher healthcare resource consumption and costs than moderate or mild asthma, due to its complex nature and heterogeneity.6–8 The spectrum of the disease is mirrored in distinct phenotypes, characterized by various clinical, functional, and quality-of-life parameters, as well as associated comorbidities.9 Multiple interventions have been attempted in an effort to optimize the management of complex chronic diseases, including severe asthma which affects an estimated 3.7–10% of asthma patients in Spain.2

The application of lean methodology to the healthcare sector reflects a strategic paradigmatic shift rooted in principles originating from manufacturing systems.10,11 This methodology aims to systematically enhance operational efficiency, reduce wasteful practices, and ultimately optimize patient outcomes. At the core of lean philosophy lies a perpetual commitment to improvement, achieved through the identification and elimination of non-value-added processes and the promotion of a culture of organizational learning and adaptability, all based on a patient-centered approach.10–12

The CARABELA initiative was developed in a holistic and transformative manner with the initial aim of optimizing healthcare processes for managing patients with severe asthma in Spain. Lean methodology was implemented to identify patient journeys, reorganize and optimize processes, and generate profound solutions that have a positive impact on the management of severe asthma. The initiative considered both patient and healthcare provider perspectives to ensure optimal outcomes from a healthcare management perspective. This laid the groundwork for transforming the management of a chronic condition like severe asthma and created a new mindset for reshaping the approach to managing other chronic diseases with comparable improvement areas in terms of healthcare burden and economic impact. The CARABELA initiative has since evolved into an action framework13 and a catalyst for transformation, and a true fleet of CARABELA initiatives have been launched.14

The CARABELA severe asthma initiative successfully outlined a set of quality healthcare quality indicators to facilitate the optimization of patient management in Spanish hospitals.14 However, to develop these healthcare quality indicators, it was necessary to thoroughly characterize the improvement areas and define strategies that, according to participating professionals, would constitute a substantial solution in the management of severe asthma patients in their hospitals. Here we describe the detailed characterization process of the healthcare model in severe asthma and the measures evaluated to establish the paradigm shift that constitutes the CARABELA severe asthma initiative.

Material and methodsLean methodologyWe used lean methodology to apply comprehensive process reengineering to design a thorough restructuring of workflows aimed at achieving significant improvements in efficiency and effectiveness.10,11 This entails a meticulous evaluation of existing processes, identification of obstacles, and the implementation of innovative solutions to bring about substantial enhancements. The integration of lean principles with process reengineering not only streamlines healthcare operations but also raises the bar for the standard of patient care,15,16 as comprehensively described elsewhere in the general methodology of the CARABELA mindset.13

Initiative designPhase 1: Characterization of the management modelDuring the initial phase of the initiative, the Scientific Committee drew up a general process flowchart to characterize the management of patients with severe asthma to serve as a starting point to delineate the different models for the pilot centers.

We subsequently selected six pilot centers, each of which adopted a distinct approach to the care of severe asthma patients. These approaches included management by respiratory medicine or allergology departments, collaborative management by both, with or without accreditation for an asthma unit, and with or without multidisciplinary profiles, among other variations.

After selecting the pilot center, in-person workshops were conducted at each facility with the aim of characterizing their healthcare models and identifying opportunities for optimization. These workshops involved the participation of various professional profiles engaged in the management of severe asthma patients at the hospital, including specialists in respiratory medicine, allergology, nursing staff with experience or who were dedicated to the asthma unit or the management of asthma patients, hospital pharmacy staff with experience in managing and dispensing biological medications indicated for severe asthma, and physicians from other specialties (e.g., otolaryngology, endocrinology, and psychiatry) involved in the care of severe asthma patients.

The workshops were approached collaboratively, using the basic process flowchart for severe asthma management as a foundation. The specific processes of each hospital were analyzed and depicted in detail. Professionals were asked to identify potential barriers, unmet needs, improvement areas, and distinctive elements that could be exported as best practices throughout the entire process. Potential solutions were proposed during the sessions to optimize the analyzed care processes.

Following the collaborative workshop, a comprehensive results report was compiled for each pilot center. This report encompassed the flowchart outlining the specific care process, a detailed breakdown of each subprocess within the flowchart, and the formulated courses of action.

The model for severe asthma management in each pilot center was defined in a specific care process flowchart. This entailed an analysis of the distinctive elements within each subprocess and the interactions among professionals. Furthermore, the characteristics of the health area (i.e., coverage area of each hospital) and the hospital were taken into consideration.

The detailed description of each subprocess included in the flowchart was presented in a standardized form delineating actions at each step, the professionals involved, documentation generated, information systems employed, and the necessary infrastructures and equipment. Each subprocess was linked to the healthcare quality indicators established at the initiative's inception, so that its value could be compared in detail once solutions were implemented.

The courses of action were established based on the improvement areas identified in the process. A series of action plans were outlined, each of which was associated with specific improvements. For each improvement area, both an incremental solution (leveraging available center resources and process reorganization) and a disruptive solution (utilizing exponential technologies in clinical practice, humanization of care, and efficiency) were clearly defined.

Phase 2: National Asthma Multidisciplinary WorkshopAfter completing the characterization of the six pilot centers, a National Asthma Multidisciplinary Workshop was organized to communicate the results of the first phase to asthma specialists nationwide and to outline the next steps of the initiative. This one-and-a-half-day meeting, held in Malaga on June 28 and 29, 2019, brought together 80 participants, including managers, clinicians, innovators, and lean methodology experts, providing a platform to discuss the approach to severe asthma patients.

The multidisciplinary workshop focused on defining the optimized asthma unit of the future. Discussions covered the crucial role of management and healthcare quality indicators as indispensable tools in clinical activity. An interactive voting session was conducted in which attendees used the Power Vote tool to prioritize improvement areas and opportunities in asthma management. A total of 80 participants identified and prioritized 20 improvement areas and opportunities.

Phase 3: Regional MeetingsFollowing the work in the pilot centers, six regional meetings were held to bring together healthcare professionals of multidisciplinary profiles to discuss unmet needs and improvement areas in severe asthma management, and to identify and prioritize potential solutions.

Representative healthcare centers from as many provinces as possible across Spain were included in the six regional meetings to capture a broad spectrum of realities in severe asthma management in Spain. The meetings involved 100 professionals from respiratory medicine, allergology, nursing, and hospital pharmacies, representing a total of 61 centers (Supplementary Table 1.).

A list of solutions was generated and categorized into four categories based on their impact on the process flowchart: coordination and protocols, diagnostic tests and equipment, information systems, and patient experience. Participants prioritized the list of solutions by assigning scores from 1 to 10, with 1 being the least important and 10 being the most important, using the Mentimeter tool.17 This placed the proposed solutions in order and facilitated discussions on the results with the participants.

Participants also expressed their degree of agreement with a list of healthcare quality indicators generated in the initiative by the Coordinating and Scientific Committees described elsewhere.14

Phase 4: Dissemination and implementationFor the final phase, the results of the previous phases have been integrated into a digital tool in the form of a Playbook, focused on disseminating and applying the models, solutions, and variables. This is implemented in a series of workshops organized upon request at individual healthcare centers across Spain.

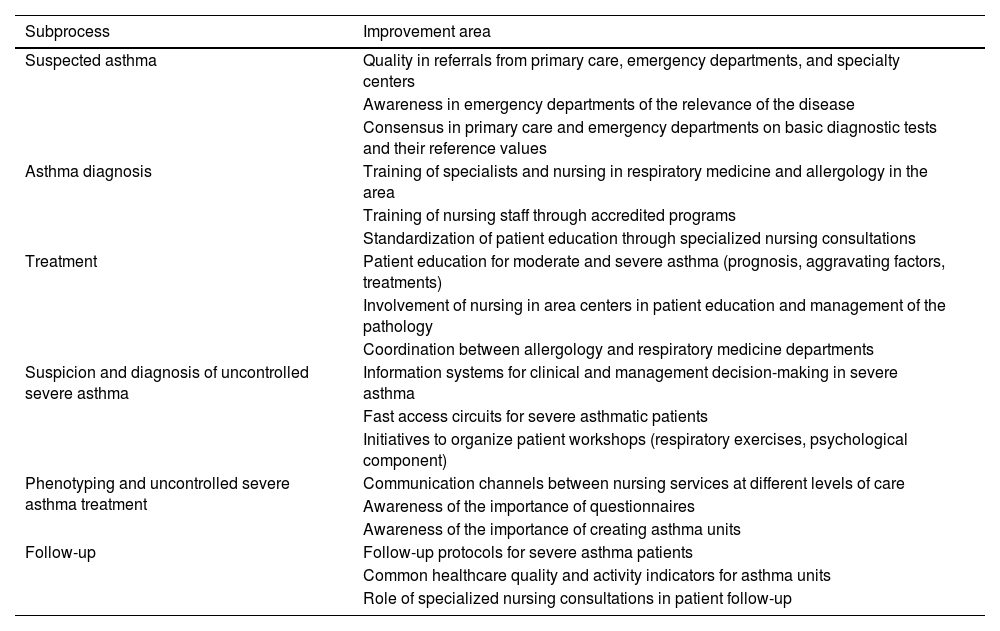

ResultsPhase 1: Characterization of pilot centersThe care model of six Spanish hospitals was characterized by analyzing the processes and subprocesses associated with the treatment of severe asthma patients. Potential improvement areas were identified from the insights of healthcare professionals, revealing opportunities for further development. Table 1 outlines the identified improvement areas categorized according to the subprocess in which they were identified.

Improvement areas identified in the pilot centers by subprocess.

| Subprocess | Improvement area |

|---|---|

| Suspected asthma | Quality in referrals from primary care, emergency departments, and specialty centers |

| Awareness in emergency departments of the relevance of the disease | |

| Consensus in primary care and emergency departments on basic diagnostic tests and their reference values | |

| Asthma diagnosis | Training of specialists and nursing in respiratory medicine and allergology in the area |

| Training of nursing staff through accredited programs | |

| Standardization of patient education through specialized nursing consultations | |

| Treatment | Patient education for moderate and severe asthma (prognosis, aggravating factors, treatments) |

| Involvement of nursing in area centers in patient education and management of the pathology | |

| Coordination between allergology and respiratory medicine departments | |

| Suspicion and diagnosis of uncontrolled severe asthma | Information systems for clinical and management decision-making in severe asthma |

| Fast access circuits for severe asthmatic patients | |

| Initiatives to organize patient workshops (respiratory exercises, psychological component) | |

| Phenotyping and uncontrolled severe asthma treatment | Communication channels between nursing services at different levels of care |

| Awareness of the importance of questionnaires | |

| Awareness of the importance of creating asthma units | |

| Follow-up | Follow-up protocols for severe asthma patients |

| Common healthcare quality and activity indicators for asthma units | |

| Role of specialized nursing consultations in patient follow-up |

A total of 87 improvement areas were identified and associated with potential initiatives that could have an impact on them. When considering the subprocesses where improvement areas and solutions were identified, 62% were linked to the suspicion and diagnosis of asthma (45.9% and 16.1% areas for asthma and uncontrolled severe asthma, respectively), with a particular emphasis on enhancing coordination between care levels and specialties. It is essential to highlight that early diagnosis is a significant improvement area in managing severe asthma, a fact acknowledged by specialists. Consequently, specific solutions tailored to each center were proposed with this objective in mind. The remaining improvement areas were evenly distributed among the remaining subprocesses (14.9% each for improvement areas and solutions in phenotyping and uncontrolled severe asthma treatment and follow-up, and 8.1% for improvement areas and solutions in treatment).

The most notable improvement areas were associated with raising awareness about the condition across all care levels, recognizing the crucial role of nursing in managing the condition, understanding the importance of providing comprehensive education and training for patients, and acknowledging the necessity to develop efficient communication systems among professionals and with patients (Table 1).

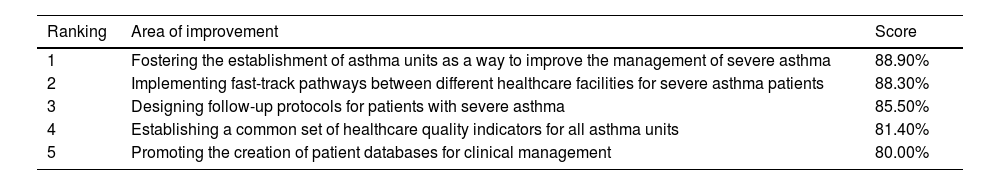

Phase 2: National WorkshopDuring the National Workshop, participants prioritized 20 questions, rating them from 1 to 5 (1 indicating low importance and 5 indicating high importance) to assess improvement areas in the management of severe asthma patients. The top five areas identified as most critical, with a priority level of 4 or 5, included fostering the establishment of asthma units to improve the management of the condition, implementing fast-track pathways between different healthcare facilities (e.g., between primary care or the emergency room and asthma units) for severe asthmatic patients, designing follow-up protocols for patients with severe asthma, establishing a common set of healthcare quality indicators for all asthma units, and promoting the creation of patient databases for clinical management (Table 2).

Solutions considered highest priority based on the results obtained in the National Workshop meeting vote.

| Ranking | Area of improvement | Score |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fostering the establishment of asthma units as a way to improve the management of severe asthma | 88.90% |

| 2 | Implementing fast-track pathways between different healthcare facilities for severe asthma patients | 88.30% |

| 3 | Designing follow-up protocols for patients with severe asthma | 85.50% |

| 4 | Establishing a common set of healthcare quality indicators for all asthma units | 81.40% |

| 5 | Promoting the creation of patient databases for clinical management | 80.00% |

Scores were calculated based on the number of attendees who rated the response with a priority level of 4 or 5, out of the total.

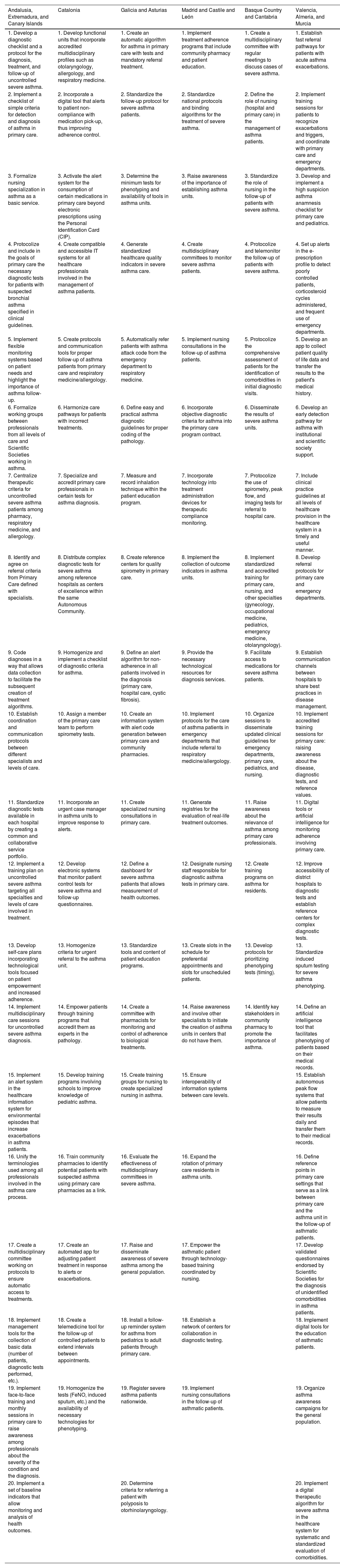

In the regional meetings, a total of 144 items were identified as improvement areas where efforts could be made to optimize the management of patients with severe asthma. All delineated improvement areas, meticulously identified and prioritized during these regional discussions, are presented in Table 3.

Priority solutions in each of the regional meetings.

| Andalusia, Extremadura, and Canary Islands | Catalonia | Galicia and Asturias | Madrid and Castile and León | Basque Country and Cantabria | Valencia, Almeria, and Murcia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Develop a diagnostic checklist and a protocol for the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of uncontrolled severe asthma. | 1. Develop functional units that incorporate accredited multidisciplinary profiles such as otolaryngology, allergology, and respiratory medicine. | 1. Create an automatic algorithm for asthma in primary care with tests and mandatory referral treatment. | 1. Implement treatment adherence programs that include community pharmacy and patient education. | 1. Create a multidisciplinary committee with regular meetings to discuss cases of severe asthma. | 1. Establish fast referral pathways for patients with acute asthma exacerbations. |

| 2. Implement a checklist of simple criteria for detection and diagnosis of asthma in primary care. | 2. Incorporate a digital tool that alerts to patient non-compliance with medication pick-up, thus improving adherence control. | 2. Standardize the follow-up protocol for severe asthma patients. | 2. Standardize national protocols and binding algorithms for the treatment of severe asthma. | 2. Define the role of nursing (hospital and primary care) in the management of asthma patients. | 2. Implement training sessions for patients to recognize exacerbations and triggers, and coordinate with primary care and emergency departments. |

| 3. Formalize nursing specialization in asthma as a basic service. | 3. Activate the alert system for the consumption of certain medications in primary care beyond electronic prescriptions using the Personal Identification Card (CIP). | 3. Determine the minimum tests for phenotyping and availability of tools in asthma units. | 3. Raise awareness of the importance of establishing asthma units. | 3. Standardize the role of nursing in the follow-up of patients with severe asthma. | 3. Develop and implement a high suspicion asthma anamnesis checklist for primary care and pediatrics. |

| 4. Protocolize and include in the goals of primary care the necessary diagnostic tests for patients with suspected bronchial asthma specified in clinical guidelines. | 4. Create compatible and accessible IT systems for all healthcare professionals involved in the management of asthma patients. | 4. Generate standardized healthcare quality indicators in severe asthma care. | 4. Create multidisciplinary committees to monitor severe asthma patients. | 4. Protocolize and telemonitor the follow-up of patients with severe asthma. | 4. Set up alerts in the e-prescription profile to detect poorly controlled patients, corticosteroid cycles administered, and frequent use of emergency departments. |

| 5. Implement flexible monitoring systems based on patient needs and highlight the importance of asthma follow-up. | 5. Create protocols and communication tools for proper follow-up of asthma patients from primary care and respiratory medicine/allergology. | 5. Automatically refer patients with asthma attack code from the emergency department to respiratory medicine. | 5. Implement nursing consultations in the follow-up of asthma patients. | 5. Protocolize the comprehensive assessment of patients for the identification of comorbidities in initial diagnostic visits. | 5. Develop an app to collect patient quality of life data and transfer the results to the patient's medical history. |

| 6. Formalize working groups between professionals from all levels of care and Scientific Societies working in asthma. | 6. Harmonize care pathways for patients with incorrect treatments. | 6. Define easy and practical asthma diagnostic guidelines for proper coding of the pathology. | 6. Incorporate objective diagnostic criteria for asthma into the primary care program contract. | 6. Disseminate the results of severe asthma units. | 6. Develop an early detection pathway for asthma with institutional and scientific society support. |

| 7. Centralize therapeutic criteria for uncontrolled severe asthma patients among pharmacy, respiratory medicine, and allergology. | 7. Specialize and accredit primary care professionals in certain tests for asthma diagnosis. | 7. Measure and record inhalation technique within the patient education program. | 7. Incorporate technology into treatment administration devices for therapeutic compliance monitoring. | 7. Protocolize the use of spirometry, peak flow, and imaging tests for referral to hospital care. | 7. Include clinical practice guidelines at all levels of healthcare provision in the healthcare system in a timely and useful manner. |

| 8. Identify and agree on referral criteria from Primary Care defined with specialists. | 8. Distribute complex diagnostic tests for severe asthma among reference hospitals as centers of excellence within the same Autonomous Community. | 8. Create reference centers for quality spirometry in primary care. | 8. Implement the collection of outcome indicators in asthma units. | 8. Implement standardized and accredited training for primary care, nursing, and other specialties (gynecology, occupational medicine, pediatrics, emergency medicine, otolaryngology). | 8. Develop referral protocols for primary care and emergency departments. |

| 9. Code diagnoses in a way that allows data collection to facilitate the subsequent creation of treatment algorithms. | 9. Homogenize and implement a checklist of diagnostic criteria for asthma. | 9. Define an alert algorithm for non-adherence in all patients involved in the diagnosis (primary care, hospital care, cystic fibrosis). | 9. Provide the necessary technological resources for diagnosis services. | 9. Facilitate access to medications for severe asthma patients. | 9. Establish communication channels between hospitals to share best practices in disease management. |

| 10. Establish coordination and communication protocols between different specialists and levels of care. | 10. Assign a member of the primary care team to perform spirometry tests. | 10. Create an information system with alert code generation between primary care and community pharmacies. | 10. Implement protocols for the care of asthma patients in emergency departments that include referral to respiratory medicine/allergology. | 10. Organize sessions to disseminate updated clinical guidelines for emergency departments, primary care, pediatrics, and nursing. | 10. Implement accredited training sessions for primary care: raising awareness about the disease, diagnostic tests, and reference values. |

| 11. Standardize diagnostic tests available in each hospital by creating a common and collaborative service portfolio. | 11. Incorporate an urgent case manager in asthma units to improve response to alerts. | 11. Create specialized nursing consultations in primary care. | 11. Generate registries for the evaluation of real-life treatment outcomes. | 11. Raise awareness about the relevance of asthma among primary care professionals. | 11. Digital tools or artificial intelligence for monitoring adherence involving primary care. |

| 12. Implement a training plan on uncontrolled severe asthma targeting all specialties and levels of care involved in treatment. | 12. Develop electronic systems that monitor patient control tests for severe asthma and follow-up questionnaires. | 12. Define a dashboard for severe asthma patients that allows measurement of health outcomes. | 12. Designate nursing staff responsible for diagnostic asthma tests in primary care. | 12. Create training programs on asthma for residents. | 12. Improve accessibility of district hospitals to diagnostic tests and establish reference centers for complex diagnostic tests. |

| 13. Develop self-care plans incorporating technological tools focused on patient empowerment and increased adherence. | 13. Homogenize criteria for urgent referral to the asthma unit. | 13. Standardize tools and content of patient education programs. | 13. Create slots in the schedule for preferential appointments and slots for unscheduled patients. | 13. Develop protocols for prioritizing phenotyping tests (timing). | 13. Standardize induced sputum testing for severe asthma phenotyping. |

| 14. Implement multidisciplinary care sessions for uncontrolled severe asthma diagnosis. | 14. Empower patients through training programs that accredit them as experts in the pathology. | 14. Create a committee with pharmacists for monitoring and control of adherence to biological treatments. | 14. Raise awareness and involve other specialists to initiate the creation of asthma units in centers that do not have them. | 14. Identify key stakeholders in community pharmacy to promote the importance of asthma. | 14. Define an artificial intelligence tool that facilitates phenotyping of patients based on their medical records. |

| 15. Implement an alert system in the healthcare information system for environmental episodes that increase exacerbations in asthma patients. | 15. Develop training programs involving schools to improve knowledge of pediatric asthma. | 15. Create training groups for nursing to create specialized nursing in asthma. | 15. Ensure interoperability of information systems between care levels. | 15. Establish autonomous peak flow systems that allow patients to measure their results daily and transfer them to their medical records. | |

| 16. Unify the terminologies used among all professionals involved in the asthma care process. | 16. Train community pharmacies to identify potential patients with suspected asthma using primary care pharmacies as a link. | 16. Evaluate the effectiveness of multidisciplinary committees in severe asthma. | 16. Expand the rotation of primary care residents in asthma units. | 16. Define reference points in primary care settings that serve as a link between primary care and the asthma unit in the follow-up of asthmatic patients. | |

| 17. Create a multidisciplinary committee working on protocols to ensure automatic access to treatments. | 17. Create an automated app for adjusting patient treatment in response to alerts or exacerbations. | 17. Raise and disseminate awareness of severe asthma among the general population. | 17. Empower the asthmatic patient through technology-based training coordinated by nursing. | 17. Develop validated questionnaires endorsed by Scientific Societies for the diagnosis of unidentified comorbidities in asthma patients. | |

| 18. Implement management tools for the collection of basic data (number of patients, diagnostic tests performed, etc.). | 18. Create a telemedicine tool for the follow-up of controlled patients to extend intervals between appointments. | 18. Install a follow-up reminder system for asthma from pediatrics to adult patients through primary care. | 18. Establish a network of centers for collaboration in diagnostic testing. | 18. Implement digital tools for the education of asthmatic patients. | |

| 19. Implement face-to-face training and monthly sessions in primary care to raise awareness among professionals about the severity of the condition and the diagnosis. | 19. Homogenize the tests (FeNO, induced sputum, etc.) and the availability of necessary technologies for phenotyping. | 19. Register severe asthma patients nationwide. | 19. Implement nursing consultations in the follow-up of asthmatic patients. | 19. Organize asthma awareness campaigns for the general population. | |

| 20. Implement a set of baseline indicators that allow monitoring and analysis of health outcomes. | 20. Determine criteria for referring a patient with polyposis to otorhinolaryngology. | 20. Implement a digital therapeutic algorithm for severe asthma in the healthcare system for systematic and standardized evaluation of comorbidities. |

Upon scrutinizing the distribution of improvement areas across each subprocess of the care flow, a discernible pattern with a uniform distribution emerged, among which the treatment domain exhibited the highest prevalence. Twenty-nine (20.1%) improvement areas were identified for treatment, indicating the need for and importance of promoting and updating of patient education in symptom management and proper treatment administration, the need to address non-adherence, and the importance of involving patients as active participants in their treatment.

Twenty-five (17.4%) improvement areas in early identification or suspicion of asthma were identified. Most highlighted the need for referral protocols between primary and hospital care, the lack of a systematic diagnostic testing in primary care, and the lack of effective communication tools between care levels.

Regarding the diagnosis of asthma, 27 (18.8%) improvement areas were identified. The role of primary care as the initial point of diagnosis and a filter for patients not requiring hospital care, the expansion of high-resolution asthma consultations and the importance of promoting health education in the condition were the principal optimization areas identified.

Eighteen (12.5%) improvement areas were detected in the early identification and diagnosis of uncontrolled severe asthma, addressing the need to standardize the diagnosis of uncontrolled severe asthma, the importance of collaboration between different specialties, and the early detection of these patients.

In the category related to phenotyping and treatment of uncontrolled severe asthma, 24 (16.7%) improvement areas were identified mainly pointing the needs related to the systematization of the phenotyping process, standardization of access to treatments and therapeutic algorithms, and the integration of psychological treatment for these patients.

Finally, regarding follow-up, 20 (13.4%) improvement areas were described including the enhancement of the nursing role in patient follow-up, the need for incorporating telemedicine systems for remote patient monitoring, and the facilitation of the follow-up process of controlled patients in primary care.

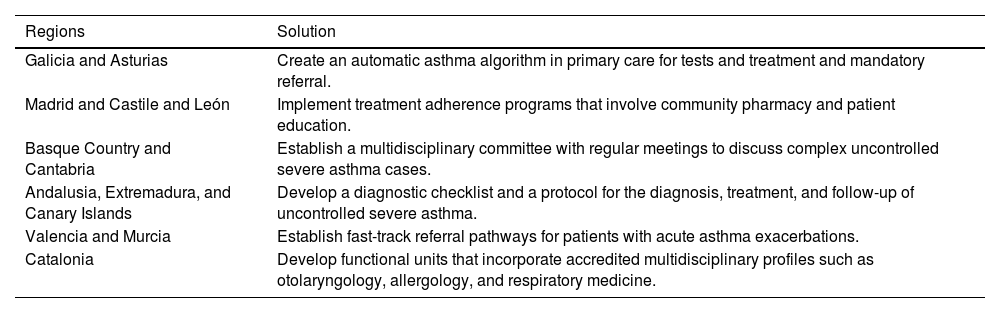

As for the solutions identified and prioritized in the regional meetings, a total of 112 solutions were cocreated. Considering their distribution by categories, 51 solutions belonged to the coordination and protocols category (45.5% of the total), information systems was the second most represented with 23 solutions (20.5% of the total), followed by patient experience with 19 (16.9%), and lastly, diagnostic tests with nine solutions (8.0%). The prioritized solution in each of the regional meetings is detailed in Table 4.

Priority solutions in each of the regional meetings.

| Regions | Solution |

|---|---|

| Galicia and Asturias | Create an automatic asthma algorithm in primary care for tests and treatment and mandatory referral. |

| Madrid and Castile and León | Implement treatment adherence programs that involve community pharmacy and patient education. |

| Basque Country and Cantabria | Establish a multidisciplinary committee with regular meetings to discuss complex uncontrolled severe asthma cases. |

| Andalusia, Extremadura, and Canary Islands | Develop a diagnostic checklist and a protocol for the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of uncontrolled severe asthma. |

| Valencia and Murcia | Establish fast-track referral pathways for patients with acute asthma exacerbations. |

| Catalonia | Develop functional units that incorporate accredited multidisciplinary profiles such as otolaryngology, allergology, and respiratory medicine. |

Workshop sessions to implement the final phase of the CARABELA initiative have been held in a total of 36 requesting hospitals. These hospitals are now implementing improvement plans tailored to their specific needs (Supplementary Table 2).

DiscussionDifferences in care models among different asthma unitsOne of the most outstanding findings of this initiative was the lack of uniformity in the management of severe asthma patients across autonomous communities, provinces, hospitals, and even within departments of the same hospital. It is important to remember that Spain is a country with a complex healthcare system, featuring a decentralized National Health System that transfers certain health responsibilities to the autonomous communities. This factor carries significant weight and explains how the medical care received by two severe asthma patients in Spain may differ depending on where they are treated. Even so, this variation should not imply a difference in the quality of healthcare delivered but rather organizational variations that confound the measurement of results, such as healthcare quality indicators and the optimization of patient care throughout the healthcare journey.

One way to address these inconsistencies is to implement specific quality standards that can be applied independently of the system or protocol used in each center. These standards should provide specific measures of the excellence of patient care or the efficiency in managing the pathology. Indeed, one of the classifications identified in this study of the asthma treatment models determines whether the asthma unit is accredited by a governing body (i.e., SEPAR or SEAIC, Spanish Scientific Societies for Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery and Allergology and Clinical Immunology, respectively). While the non-accreditation of the unit does not indicate a lack of excellent patient care, the accreditation process, endorsed by several organizations, uses benchmarks and measurements that pinpoint improvement areas to improve care for severe asthma patients and helps enhance optimization.18

Another notable difference observed among participating centers and regions in the initiative was the phenotyping process for severe asthma patients. Specifically, professionals highlighted discrepancies in the timing and centralization of this process, the availability of equipment for conducting all required tests, and multidisciplinary collaboration in diagnosis and treatment.

Furthermore, a significant number of individual initiatives undertaken by professionals and departments from different hospitals were identified, impacting the quality of care and patient experience. These initiatives constitute a partnership between Scientific Societies and the industry, primarily propelled by the dedication and time invested by clinicians and managers in developing innovative projects focused on improving care. The CARABELA mindset aims to extend this spirit to all healthcare centers and to foster a transformation process, by providing tools for consistent optimization tailored to real needs.

Additionally, key areas of action have been pinpointed where the professionals have reached a consensus, such as patient education and training, efficient collaboration between care levels (primary care and hospital care), the role of nursing in managing the condition, and the importance of a holistic multidisciplinary approach in the treatment and follow-up of severe asthma, among others.

Impact of the initiativeThe CARABELA initiative has engaged the participation of nearly 200 healthcare professionals, each offering their insights into the management of severe asthma. This extensive involvement led to the generation of a raft of innovative initiatives and ideas designed to optimize the approach to this condition. This outcome is largely due to the individual commitment of professionals to their daily practice, as reflected in the results. The institutional support provided by the various Scientific Societies that actively participated in the initiative has been crucial. Specifically, the opportunity to implement transversal initiatives born from clinicians with a focus on enhancing the quality of care and the quality of life for patients has been invaluable. In essence, clinicians act as catalysts for solution, while managers play a pivotal role in facilitating that solution.

Specific initiatives have been initiated, showcasing the enhanced value of the CARABELA mindset. These initiatives involve laying the groundwork by achieving consensus on referral recommendations for patients arriving at the emergency room with an asthma exacerbation, as well as establishing recommendations for reducing the use of glucocorticoids in the treatment of severe asthma.19,20 Also, as a final step of the initiative, a set of healthcare quality indicators were defined as a fundamental tool in solution management, allowing for the assessment of the impact of implemented measures.14 This basic set of healthcare quality indicators, developed and validated by professionals to measure the quality of care in asthma units at the national level, will serve as a first step toward standardizing patient care for asthma, enabling the assessment of quality in a similar manner. These healthcare quality indicators will simultaneously allow for the evaluation of the impact of the various initiatives implemented to optimize care and improve quality.14

ConclusionsThe CARABELA mindset applied to the present severe asthma initiative has generated a perspective in which potential improvement areas may translate into opportunities for solution. Overall, several improvement areas in the management of severe asthma pathology have been highlighted and specific solutions have been cocreated to develop a transformation process working toward optimization. After the success in proving its effectiveness, the CARABELA initiative has been established in order to provide tools for process optimization in centers managing patients with severe asthma.

FundingCARABELA-SA is a co-organization accord between scientific societies and AstraZeneca Farmacéutica Spain, Madrid, Spain.

Authors’ contributionsAll the authors participated in the content and critical review of the present article and have approved its final version.

Conflicts of interestAll authors have received support for the present manuscript (e.g., funding, provision of study materials, medical writing, article processing charges, etc.) from AstraZeneca. FJAG has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, GSK and Sanofi; has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Bial, GSK, Orion Pharma, and Sanofi; has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from AstraZeneca, GSK, Bial, Chiesi, and Sanofi; and is the director of asthma research projects at Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica (SEPAR). MB-A has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca. AC-L has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, GSK, Gebro, MSD, Zambon, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Orion Pharma, and Novartis; has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from GSK, Sanofi, Novartis, and AstraZeneca; has participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for AstraZeneca, Sanofi and GSK; and has received research funding/grants from several state agencies and non-profit foundations, and from AstraZeneca, MSD and GSK. JD-O has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Sanofi, Teva, ALK, GSK, Chiesi, and Leti; and has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Sanofi and Chiesi. MP has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, GSK, Gebro, Zambon, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Chiesi; has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, GSK and Sanofi; has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from GSK, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Chiesi; has received payment for expert testimony from GSK, Chiesi and Sanofi; and has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Sanofi, AstraZeneca and Chiesi. LPDL has received grants or contracts from AstraZeneca, Chiesi and Sanofi; has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, GSK and Sanofi; has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, GSK and Sanofi; has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Teva, Sanofi, GSK, Gilead, and Gebro; has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from AstraZeneca, Sanofi and FAES; and has participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for AstraZeneca. MS has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca; and has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca. EF, FR-L, LR, and GR are employees at Departamento médico, AstraZeneca Farmacéutica Spain. JF and JAM declare no conflict of interest.

Medical writing support for the development of this manuscript was provided by Dr. Beatriz Albuixech, Dr. Maria Giovanna Ferrario, Dr. Blanca Piedrafita, and Dr. Javier Arranz-Nicolás at Medical Statistics Consulting S.L. (Valencia) and funded by AstraZeneca, Madrid, Spain, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

The CARABELA-SA Scientific Committee consists of the following members (listed alphabetically by last name): Francisco Javier Álvarez-Gutiérrez (Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocio, Seville, Spain); Marina Blanco-Aparicio (Hospital Universitario A Coruña, Galicia, Spain); Astrid Crespo-Lessmann (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau. Barcelona); Javier Domínguez-Ortega (Hospital Universitario La Paz. Institute for Health Research [IDIPAZ], Madrid, Spain); Eunice Fitas (AstraZeneca Farmacéutica Spain, Madrid, Spain); Juan Fraj (Instituto Aragonés de Ciencias de la Salud [IACS], Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa. Zaragoza, Spain); Juan Antonio Marqués Espi (Member of the SEDISA Executive Committee; Managing Director, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant y C.E. Stma. Faz); Marta Palop Cervera (Hospital de Sagunto, Valencia, Spain); Luis Pérez de Llano (Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti, EOXI Lugo, Galicia Spain); Francisco Ramos-Lima (AstraZeneca Farmacéutica Spain, Madrid, Spain); Lucia Regadera (AstraZeneca Farmacéutica Spain, Madrid, Spain); Gustavo Resler (AstraZeneca Farmacéutica Spain, Madrid, Spain); Manuel Santiñá (Sociedad Española de Calidad Asistencial [SECA], Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer [IDIBAPS]).