The idiopathic chronic cholangitides comprise a group of hepatobiliary diseases of probable autoimmune origin that are usually asymptomatic in the initial stages and can lead to cirrhosis of the liver. Elevated cholestatic enzymes on blood tests raise suspicion of these entities. Among the idiopathic cholangitides, the most common is primary sclerosing cholangitis, which is associated with inflammatory bowel disease and with an increased incidence of hepatobiliary and digestive tract tumours. It is important to establish the differential diagnosis with IgG4-associated cholangitis, primary biliary cholangitis, and secondary cholangitides, because the therapeutic management is different. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is the best test to evaluate the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tract, and MRI also provides information about the liver and other abdominal organs. An appropriate MRCP protocol and knowledge of the different findings that are characteristic of each entity are essential to reach the correct diagnosis.

Las colangitis crónicas idiopáticas son un grupo de enfermedades hepatobiliares, de probable origen autoinmune, que suelen ser asintomáticas en sus estadios iniciales y pueden evolucionar hacia cirrosis hepática. La sospecha se establece al encontrar elevación de las enzimas de colestasis en analíticas de sangre. Entre las colangitis idiopáticas, la más frecuente es la colangitis esclerosante primaria, asociada a la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal y que conlleva una incidencia aumentada de neoplasias hepatobiliares y del tubo digestivo. Es importante establecer el diagnóstico diferencial con la colangitis asociada a IgG4, la colangitis biliar primaria y colangitis secundarias, puesto que el manejo terapéutico es diferente. La colangiopancreatografía por resonancia magnética (CPRM) es la mejor prueba para la valoración de la vía biliar intrahepática y extrahepática, y el estudio de RM proporciona información sobre el hígado y el resto de los órganos abdominales. Un adecuado protocolo de CPRM y el conocimiento de los distintos hallazgos colangiográficos característicos de cada entidad son esenciales para alcanzar un diagnóstico correcto.

The chronic cholangitides straddle a broad-spectrum of hepatobiliary disorders characterized by chronic inflammation and fibrosis of the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts, which condition a reduction in bile duct calibre and obstruction.1

More than 50% of cases are diagnosed in asymptomatic patients through an analytical pattern of chronic cholestasis. In the early stages, some patients present pruritus. Other symptoms that may emerge with disease progression include pain in the right hypochondrium, fever, jaundice, weight loss, and, in later stages, signs of chronic liver disease, liver failure, and cirrhosis. Patients with chronic cholangitides present an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma.

Many chronic cholangitides present an uncertain aetiology, probably autoimmune; they are the so-called idiopathic cholangitides, which include primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), and IgG4-related cholangiopathy.

Other patients sustain chronic repeat bile duct damage due to causes such as surgery, lithiasis, ischaemia, or other vascular alterations, parasitic infections or diseases of the bile duct, etc., which conditions a secondary chronic cholangitis. The treatment of secondary chronic cholangitides depends on the causal aetiology.

In chronic cholangitides, abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) may provide relevant diagnostic information, although magnetic resonance (MR) is regarded as the imaging technique of choice for the study of this set of diseases since it provides a comprehensive evaluation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts and also furnishes information about the changes in the liver parenchyma that occur in these patients.2

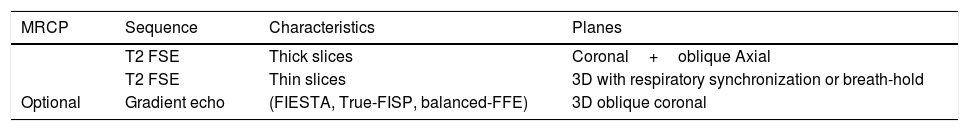

Magnetic resonance study protocol in chronic cholangitides (Table 1)Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is the best non-invasive imaging method for the study of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts on account of its high contrast resolution and spatial definition. They are heavily T2-weighted fast spin echo sequences (FSE/TSE) to accentuate the high signal of the static fluid of the bile ducts and to suppress the signal from the underlying tissues3 (Table 1).

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and liver magnetic resonance protocol in the study of cholangiopathies.

| MRCP | Sequence | Characteristics | Planes |

|---|---|---|---|

| T2 FSE | Thick slices | Coronal+oblique Axial | |

| T2 FSE | Thin slices | 3D with respiratory synchronization or breath-hold | |

| Optional | Gradient echo | (FIESTA, True-FISP, balanced-FFE) | 3D oblique coronal |

| Liver MR | Sequence | Characteristics | Planes |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | In-phase or out-of-phase+T1 Fat Sat or Dixon | Axial | |

| T2 | Fat Sat | Axial | |

| DWI | b=600–800s/mm2+b=0 | Axial | |

| Optional | T1 | Gd multiphase | Axial+coronal |

MRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; 3 D: three-dimensional; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; Fat Sat: Fat saturation; FSE: fast spin-echo; Gd: gadolinium MR: magnetic resonance.

The standard MRCP protocol includes thick slices in 2 D (40–60mm) acquired in breath holds of a few seconds, normally in coronal and oblique planes to include the hepatic ducts and the common bile duct. Axial slices may be added for the study of the intrahepatic ducts. Thin slices (1–2mm) can also be acquired for a better evaluation of the intrahepatic ducts and intraductal lesions.4 It is usually a 3 D sequence with longer acquisition times (minutes) involving respiratory synchronization or navigated echoes in order to reduce movement-induced artefacts, although they can be acquired during breath hold with modern acceleration techniques (parallel image, compressed sensing).

Coherent rapid gradient-echo sequences (SSFP: FIESTA, True-FISP, balanced-FFE, etc.) are a good complement because they show the biliary tree with hyperintense fluid and have fewer flow artefacts, although background suppression is poorer and they are more sensitive to artefacts due to magnetic susceptibilities (staples, air).

The MRI protocol in patients with chronic cholangitides should also include T1- and T2-weighted anatomical images without and with fat suppression (or Dixon) and diffusion-weighted images to evaluate the bile duct wall and possible alterations of the liver parenchyma. A dynamic study with contrast is required when a neoplasm is suspected and can help to characterize inflammatory lesions. Partial hepatobiliary excretion contrasts provide functional information and make it possible to obtain an excretion cholangiography, although they have not demonstrated a clear advantage in the study of chronic cholangitides.3,5

Idiopathic chronic cholangitidesPrimary sclerosing cholangitisPrimary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic cholestatic hepatobiliary disease of unknown cause. Inflammation phenomena and fibrosis cause progressive strictures of the intra-and extrahepatic bile ducts. Their evolution is very variable; they may progress through to cirrhosis and liver failure, with a median pre-liver transplant survival of 10–12 years as of diagnosis.

Up to 70% of patients with PSC also have inflammatory bowel disease, mainly ulcerative colitis (up to 90% in a routine colon biopsy), normally diagnosed before PSC. However, only 5%-10% of patients diagnosed with ulcerative colitis develop PSC in the course of their life, and therefore cholangiography is only recommended in patients with inflammatory bowel disease when there is an analytical suspicion.

The clinical suspicion of PSC emerges when an analytical pattern of chronic cholestasis is detected (elevated serum alkaline phosphatase), with most patients being asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. The onset of symptoms, mainly fatigue and pruritus, is related to a poorer survival.

The characteristic histological finding of PSC is periductal (“onion skinning”) fibrosis with minimal inflammatory infiltration. Nevertheless, fewer than 20% of liver biopsies performed on patients with PSC yield specific findings, meaning they are not routinely recommended for diagnostic purposes.6

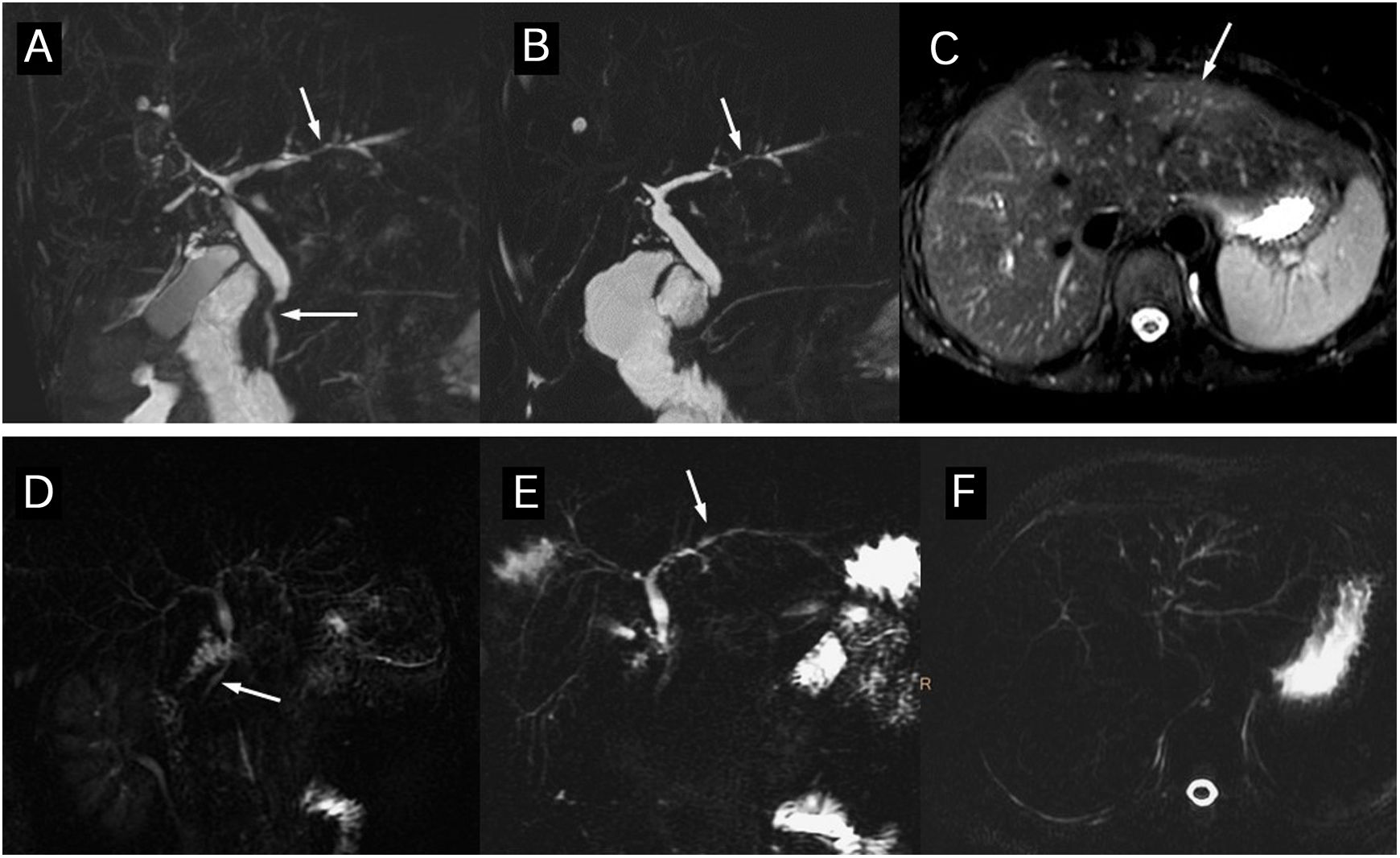

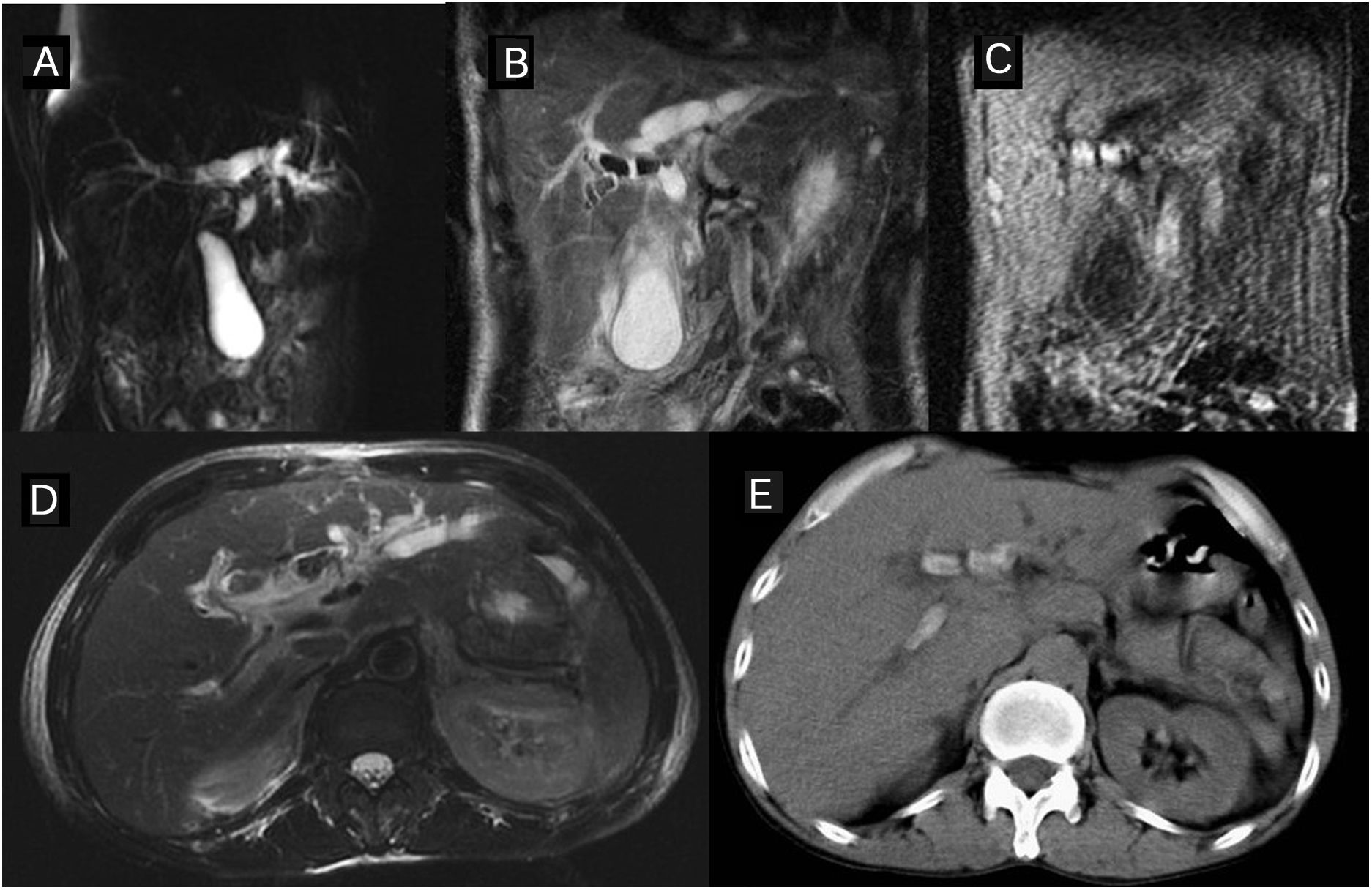

If there is a clinical-analytical suspicion of BSE, a bile duct study should be performed. The European and American clinical guidelines recommend a MR cholangiography study, since it is more sensitive than ultrasound or CT scan and also avoids the risks of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) or percutaneous cholangiography. The most common cholangiographic finding is an abnormal biliary tree caused by short and multi-focal stenoses alternating with normal or moderately-dilated bile ducts, yielding a “rosary” appearance in the bile ducts.7 75% of patients present involvement of both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct,6 while extrahepatic involvement alone is very rare. Areas of circumferential stenosis and saccular or diverticular dilations of the bile duct can be identified (Fig. 1). The degree of dilation is less than in other obstructive causes due to the periductal fibrosis. In early stages, the involvement of the intrahepatic bile ducts may be subtle, so the diagnosis calls for a careful MRCP technique and a detailed evaluation to identify mild stenoses or dilations of the ducts instead of the normal calibre reduction pattern from the centre to the periphery. In more advanced cases, stenoses make it difficult to fill the peripheral bile ducts, prompting a “pruned tree” appearance on the ERCP. Gallbladder and cystic duct alterations may be identified, usually associated with extrahepatic bile duct involvement (Fig. 2).

Diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). (A–C) 45-year-old woman with ulcerative colitis. The thick-slice (A) and thin-slice (B) MRCP images show stenosis in the common bile duct and intrahepatic ducts (arrows) with slight pre-stenotic dilation and some diverticular dilation. The T2 image with fat suppression (C) shows triangular augmented signal areas in the liver parenchyma (arrow). (D–F) Thick-slice MRCP images from another patient, a 25-year-old man with ulcerative colitis in radial (D and E) and axial (F) slices. A change of calibre is observed in the common bile duct and the intrahepatic ducts present a slight rosary appearance (arrows). The axial slice shows intrahepatic segmental involvement. Both patients had had a previous magnetic resonance cholangiography study a few months previously reported as normal.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) Wall thickening and bile duct enhancement. 37-year-old man with PSC. The thick-slice magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (A) shows multiple areas of stenoses and dilation of the intra- and extra-hepatic bile ducts. The images of the dynamic study with intravenous contrast in the arterial (B) and interstitial (C) phases show long wall thickening, with a smooth outline, of the right and common hepatic duct wall with early and maintained continuous enhancement. The lumen is thinner and there are no focal enhancements.

The diagnosis of PSC may be established when the typical imaging findings are present and secondary causes of cholangitis have been ruled out. 5% of PSC cases have a normal cholangiography because in these cases the disease only affects small-calibre intrahepatic ducts. “Small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis” is a variant of PSC with a better long-term prognosis5 and presents with cholestasis without cholangiographic alterations, whereby it is an indication for a liver biopsy which usually yields characteristic findings in these patients.

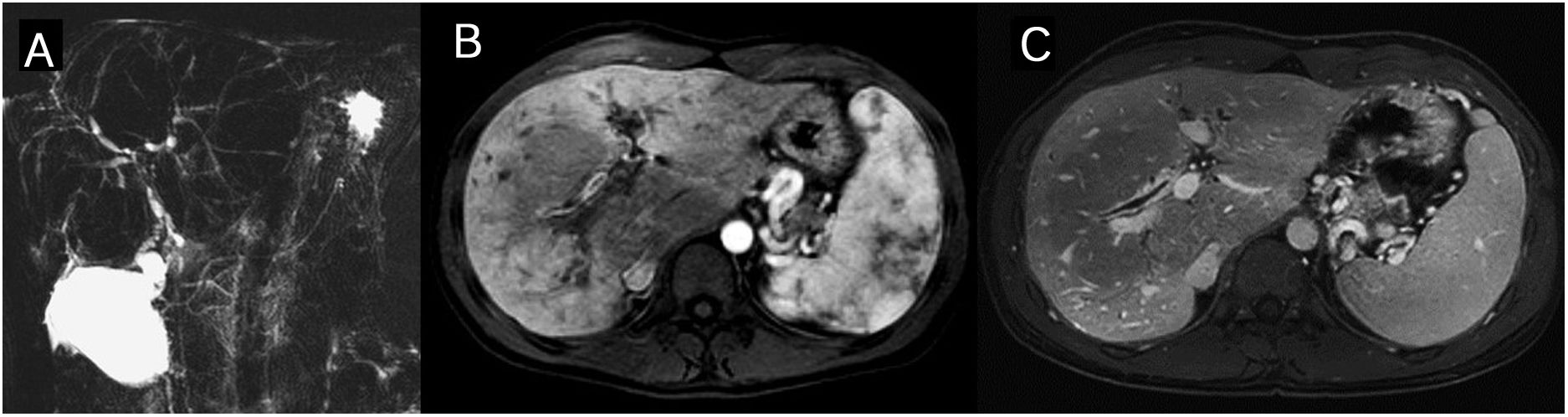

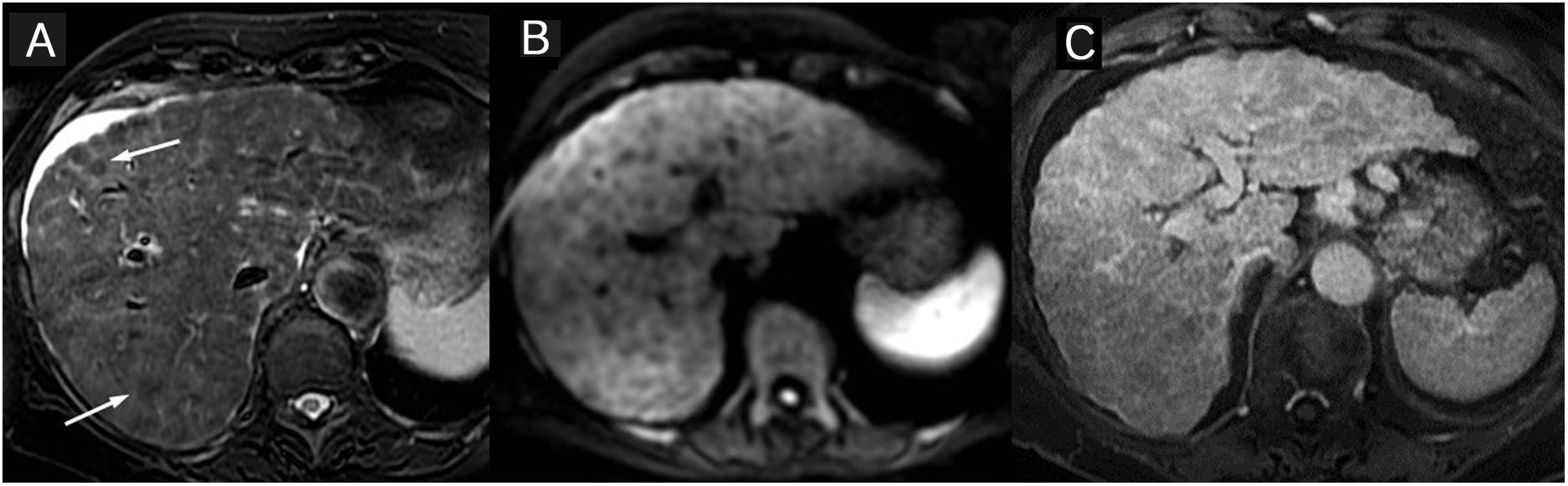

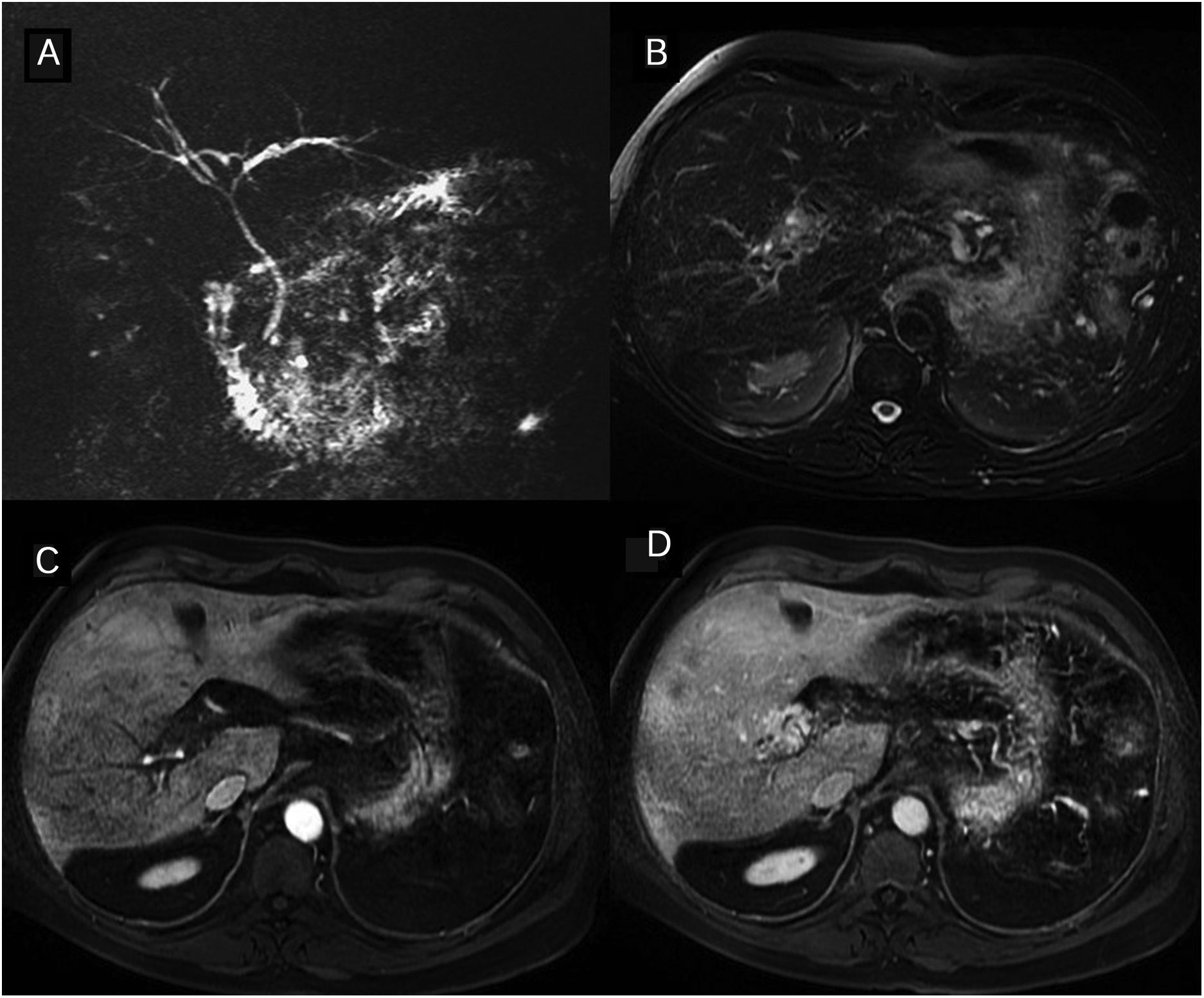

Patients with PSC frequently present liver parenchyma alterations that can be detected in MR studies. The liver tends to take on a rounded morphology because the caudate lobe is hypertrophied and the posterior segments of the right hepatic lobe and the lateral segments of the left lobe are atrophied.8 Geographical areas (normally peripheral and wedge-shaped) appear with a high parenchyma signal intensity on T2 and diffusion due to oedema, and cholestasis-related inflammation and fibrosis (Fig. 3). Signs of periportal oedema and adenopathies are also frequent. In the more advanced stages there is splenomegaly and signs of portal hypertension (Fig. 4 and Table 2).

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) Segmental alterations of the liver parenchyma on the magnetic resonance. The signal is increased in the T2- and diffusion-weighted images (b=800s/mm2) in the posterior segments of the right hepatic lobe and the lateral segments of the left lobe. The arterial phase of the dynamic study with gadolinium contrast shows a regional flow alteration which in this patient is also accompanied by hepatic steatosis with segmental distribution (out-of-phase T1 image).

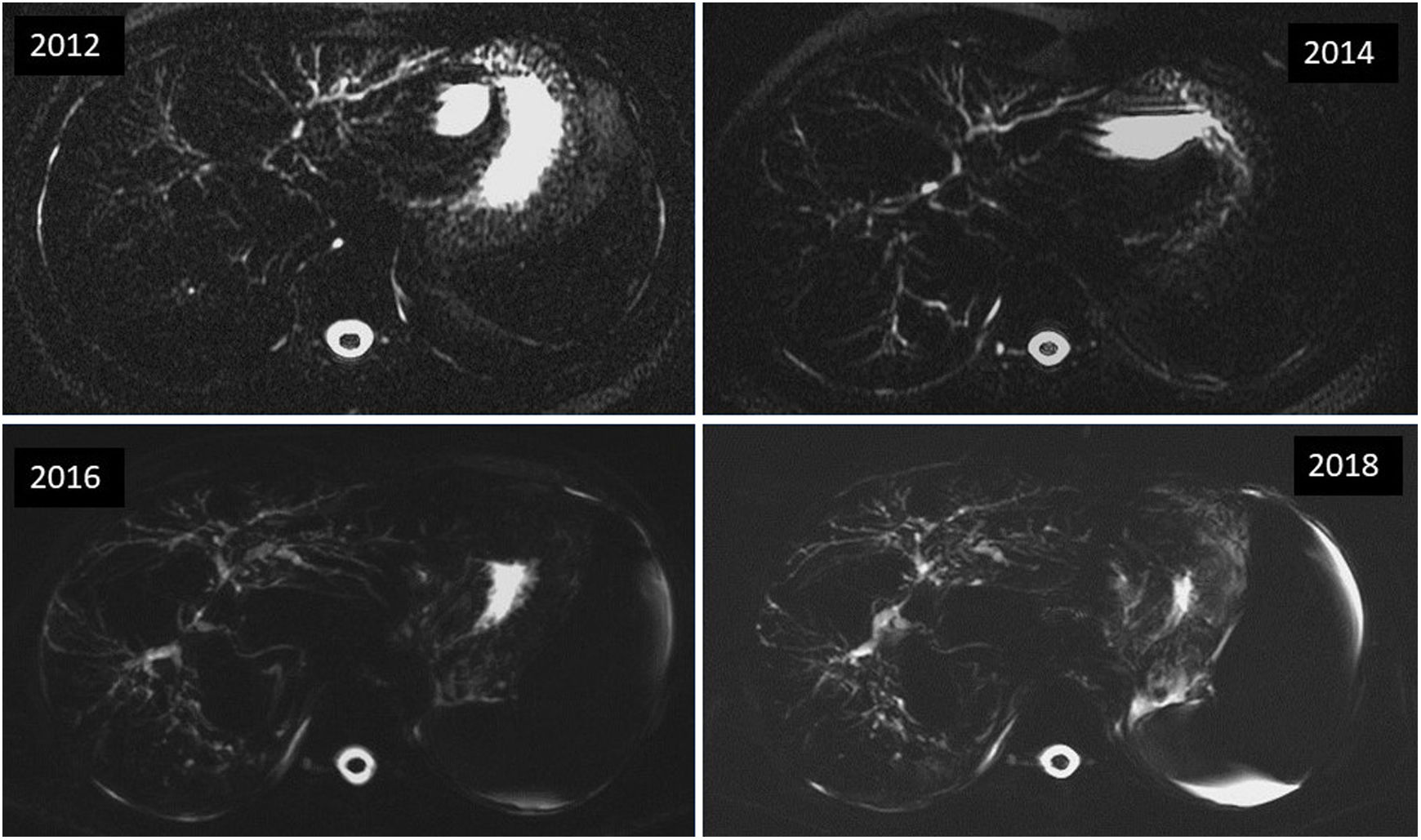

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) Disease progression on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Axial MRCP images with thick sections of a male patient with PSC showing rapid disease progression with progressive worsening of the cholangiographic findings. The previous magnetic resonance study had already showed clear signs of hepatic cirrhosis and portal hypertension, ascites, and splenomegaly (in other sequences, not shown here).

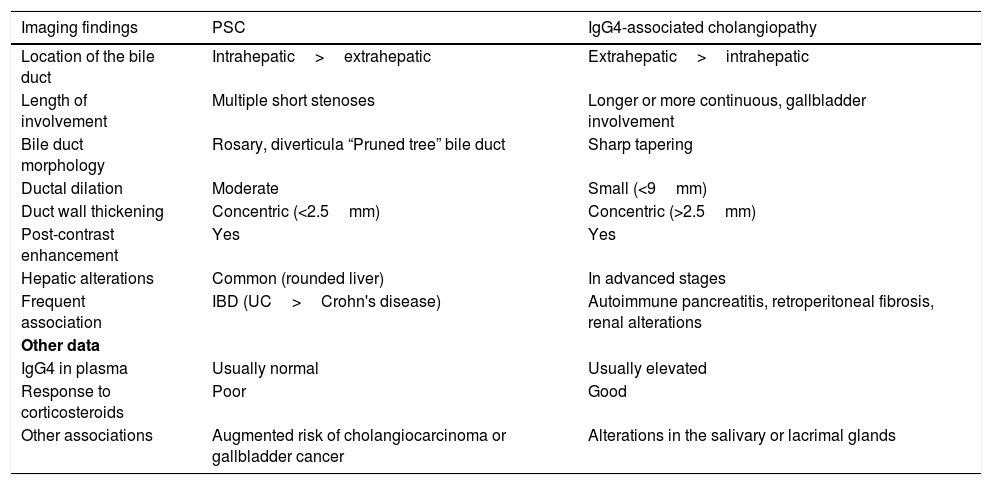

Characteristics of primary sclerosing cholangitis and IgG4-associated cholangiopathy.

| Imaging findings | PSC | IgG4-associated cholangiopathy |

|---|---|---|

| Location of the bile duct | Intrahepatic>extrahepatic | Extrahepatic>intrahepatic |

| Length of involvement | Multiple short stenoses | Longer or more continuous, gallbladder involvement |

| Bile duct morphology | Rosary, diverticula “Pruned tree” bile duct | Sharp tapering |

| Ductal dilation | Moderate | Small (<9mm) |

| Duct wall thickening | Concentric (<2.5mm) | Concentric (>2.5mm) |

| Post-contrast enhancement | Yes | Yes |

| Hepatic alterations | Common (rounded liver) | In advanced stages |

| Frequent association | IBD (UC>Crohn's disease) | Autoimmune pancreatitis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, renal alterations |

| Other data | ||

| IgG4 in plasma | Usually normal | Usually elevated |

| Response to corticosteroids | Poor | Good |

| Other associations | Augmented risk of cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder cancer | Alterations in the salivary or lacrimal glands |

PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis; UC: ulcerative colitis; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

T1-weighted sequences, following the administration of intravenous paramagnetic contrast are the most sensitive for demonstrating circumferential bile duct wall thickening with moderate late enhancement secondary to the inflammatory process and fibrosis. In the arterial phase images, liver parenchyma enhancement is often heterogeneous and reflects regional hepatic inflammatory changes.

Elastography techniques (based on ultrasound or MR) are useful for evaluating the degree of liver fibrosis in PSC and in other entities associated with chronic liver disease. Magnetic resonance elastography is a technique that is currently not widely available, although in the future it may complement the evaluation of patients with PSC.9,10

Patients with PSC are at greater risk of developing cholangiocarcinomas (up to 10%) as well as gallbladder and colorectal cancer. The early diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma is not simple due to the presence of multiple biliary strictures with wall thickening. It may be suspected when an abrupt stricture is identified, which has progressed over time, with greater wall thickening engrossment or a greater uptake of contrast in late phases.1 In advance tumours there may be signs of vascular involvement or infiltration of the liver parenchyma.

A dominant stricture, a term derived from ERCP, is defined as stricture of the common hepatic duct, less than 1.5mm in diameter, or of the left or right hepatic ducts, less than 1mm in diameter. The presence of dominant stricture is associated with a poor prognosis and a greater risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma.9,11 In these cases, ERCP or cholangioscopy are more useful because a sample of the zone can be obtained to evaluate the presence of malignancy.

Up to 2% of patients with PSC will develop gallbladder cancer, which has a poor prognosis in advanced disease stages.11 The risk of developing colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis is fourfold when it coexists with the diagnosis of PSC. Moreover, hepatocellular carcinoma is related to cirrhosis (end-stage PSC) although it is very infrequent in patients with PSC.4

The American College of Gastroenterology's 2015 clinical practice guidelines recommend screening for cholangiocarcinoma with frequent ultrasound or MR, the determination of the CA 19-9 antigen, a periodic colonoscopy and cholecystectomy if polyps of more than 8mm are detected, although the level of evidence of this screening is low.12

More than 25% of patients with PSC may develop autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), known as PSC-AIH overlap syndrome.13 For this reason, MRCP is recommended in the evaluation of patients with AIH, particularly when the response to treatment with corticosteroids is poor.

IgG4-associated cholangitisAlso known as IgA4-associated sclerosing cholangitis or autoimmune cholangiopathy, it is the manifestation, in the bile ducts, of immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-related disease, a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by increased levels of IgG4 in serum and by the infiltration of the tissues affected by plasma cells positive for IgG4 which can affect different organs.

The bile ducts are the second organ affected in this disease after the pancreas. IgG4-associated cholangitis is associated with autoimmune pancreatitis (type 1) in up to 90% of patients,14 whereas 39% of the cases of autoimmune pancreatitis present signs of cholangitis.15 Occasionally, IgG4-associated cholangitis is associated with other IgG4-related diseases such as dacryoadenitis/sialadenitis and, in the abdomen, retroperitoneal fibrosis and kidney involvement.16 It is more frequent in men, and the median age of diagnosis is higher than in PSC.

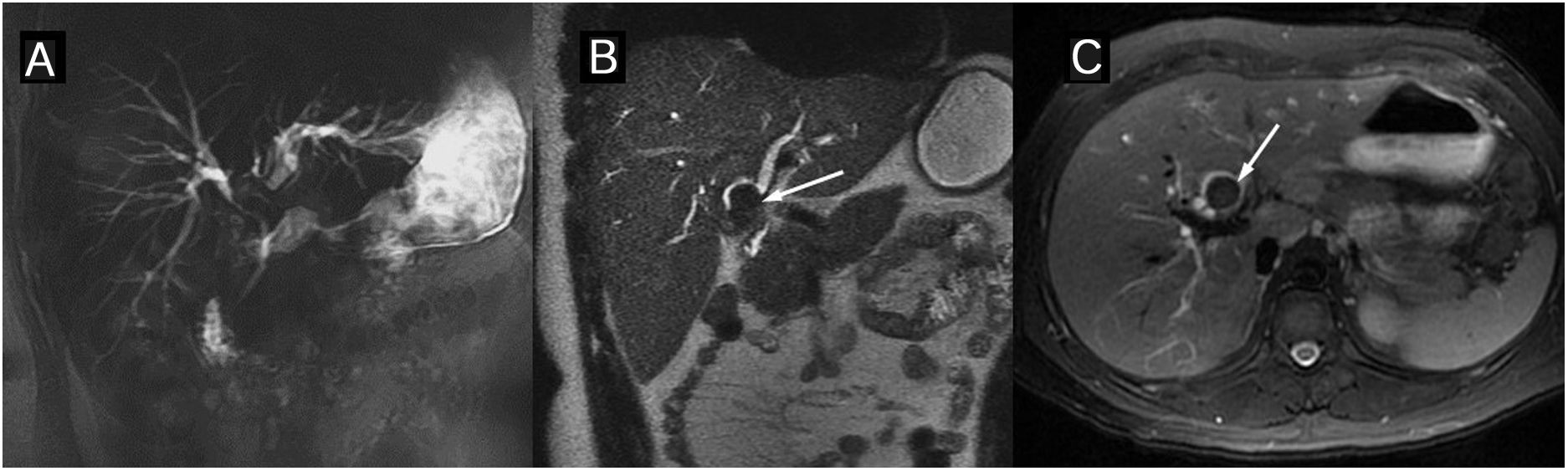

The typical MR findings include circumferential wall thickening and late enhancement of contrast in long segments of the bile duct associated with prestenotic dilations. The extrahepatic ducts tend to be more impacted. In order of frequency, the most affected segments are the intrapancreatic common bile duct, the bile ducts in hilum and the intrahepatic ducts (Fig. 5).

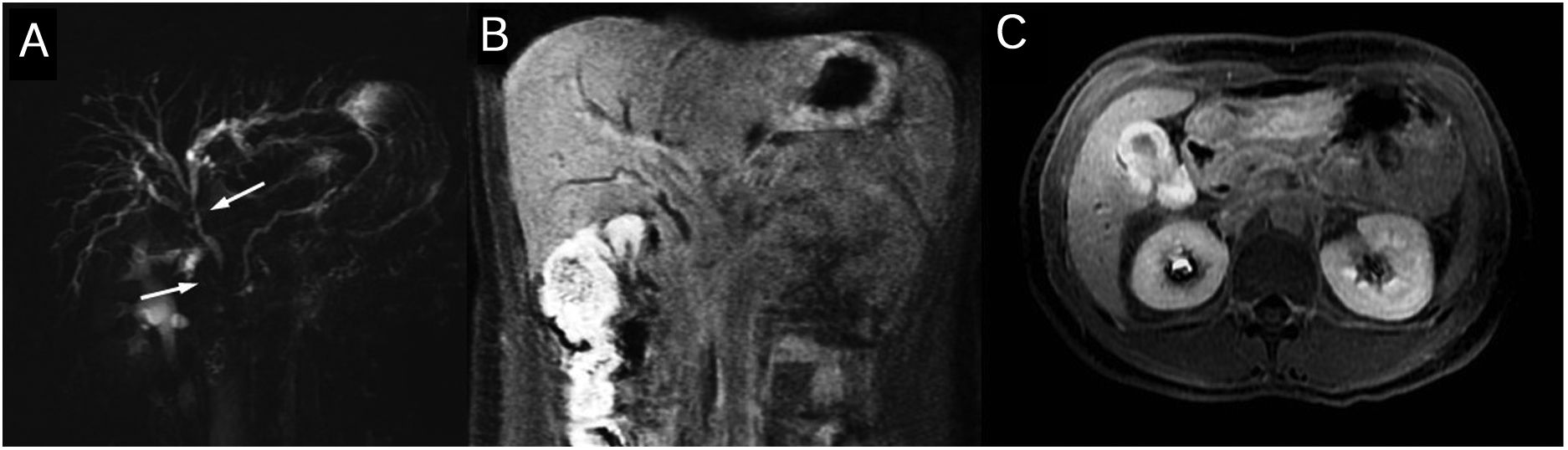

gG4-associated cholangiopathy. The thick-cut magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (A) shows stenosis of the distal common bile duct in the common and right hepatic duct in the hiliar region (arrows) with proximal dilation of the bile duct. The coronal (B) and axial (C) late-phase contrast images show wall thickening and enhancement in the biliary stenosis areas and on the vascular wall.

There are radiological signs that may suggest IgG4-associated cholangitis, although it may be difficult to distinguish between the latter and other entities such as PSC or bile duct cancer. It is important to evaluate the type of distribution (distal, several locations) and morphology of the stenoses (smooth wall thickening, sometimes with visible lumen) and to search for pancreatic, renal or retroperitoneal alterations, since these findings firmly support the diagnosis of autoimmune cholangitis (Fig. 6).17–21 IgG4-associated cholangitis normally responds well to treatment with corticosteroids, and this should therefore be considered in the radiological report if the findings are consistent (Table 2).

IgG4-associated cholangitis Involvement of other abdominal organs. 63-year-old patient with cholestasis. The ultrasound showed moderate dilation of the bile duct and thickening of the suprapancreatic common bile duct wall. The magnetic resonance study showed alterations consistent with autoimmune pancreatitis and signs of nephritis, also related to IgG4 (B: T2-weighted image, C: diffusion-weighted image b=800mm/s2, D: apparent diffusion coefficient map, ADC).

The HISORt criteria,22 first described in the Mayo Clinic, have been mainstreamed for the diagnosis of IgG4-related diseases and include a combination of criteria based on histology (H), imaging (I), serology (S), involvement of other organs (O) and response to treatment (Rt). The IgG4-associated sclerosing cholangitis diagnostic criteria of the Japan Biliary Association are similar but specifically target the differential diagnosis of PSC and cholangiocarcinoma.23

Primary biliary cholangitisPrimary biliary cholangitis (PBC), formerly called primary biliary cirrhosis, is a chronic non-suppurative cholestatic liver disease of unknown aetiology and autoimmune pathogenesis that destroys the small-calibre intrahepatic bile ducts. It mainly affects middle-aged women (90%).24 It is a slow-coursing disease that may evolve into hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, and in some cases liver failure. The classic triad of this entity is chronic cholestasis, the presence of antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) in serum, and nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis of the intrahepatic bile ducts.

The diagnosis of PBC is made on the basis of the following three criteria: serum AMA titre above 1:40, alkaline phosphatase more than 1.5 times the limit of normality for more than 24 weeks, and consistent hepatic histology.25

Histologically, PBC manifests as a periportal inflammation that progresses towards necrosis and the destruction of small- and medium-sized bile ducts. Four stages have been described in PBC: cholangitis or portal hepatitis (stage 1); periportal fibrosis or periportal hepatitis (stage 2); septal fibrosis, necrosis in bridges or both (stage 3); and biliary cirrhosis (stage 4).26

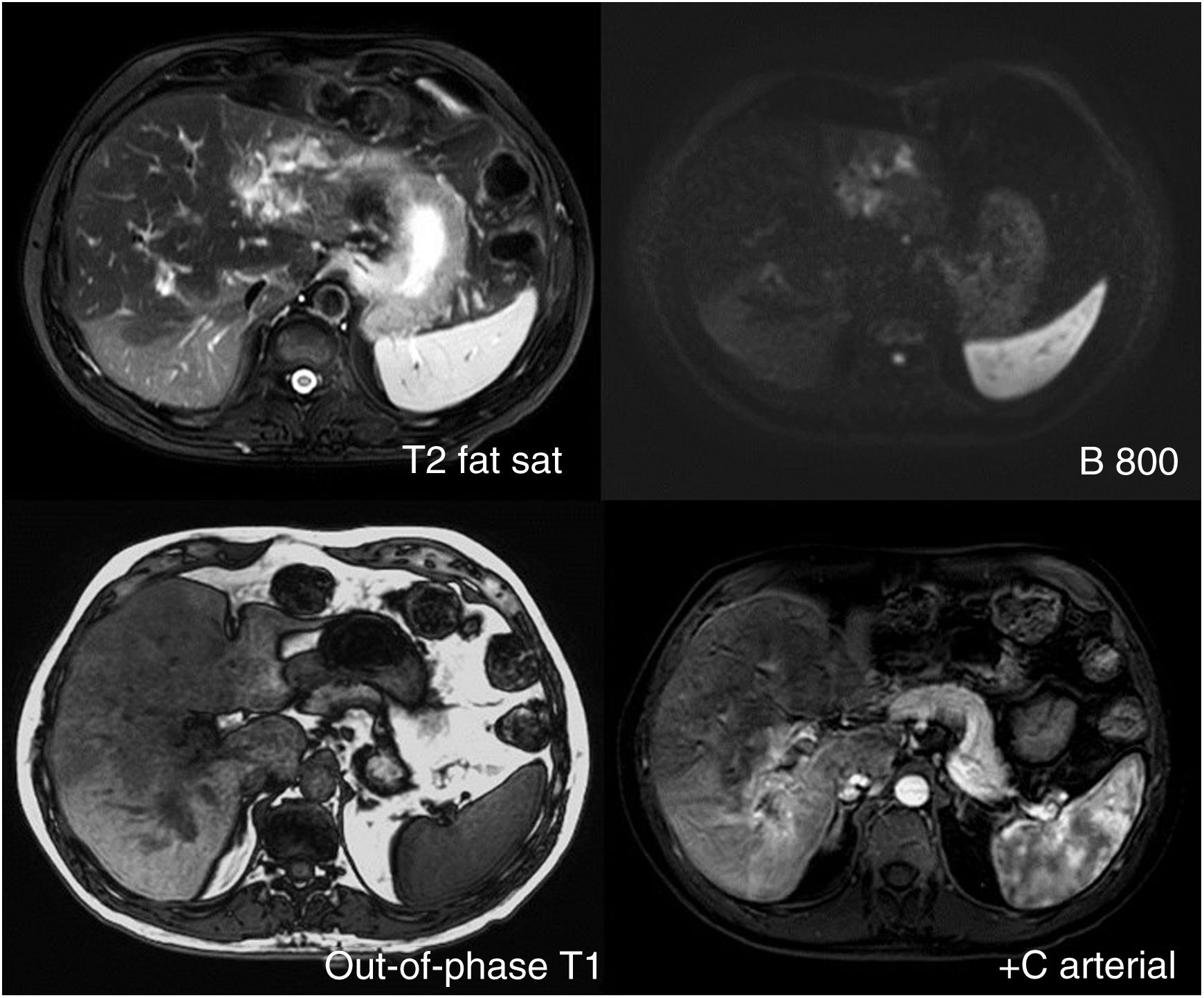

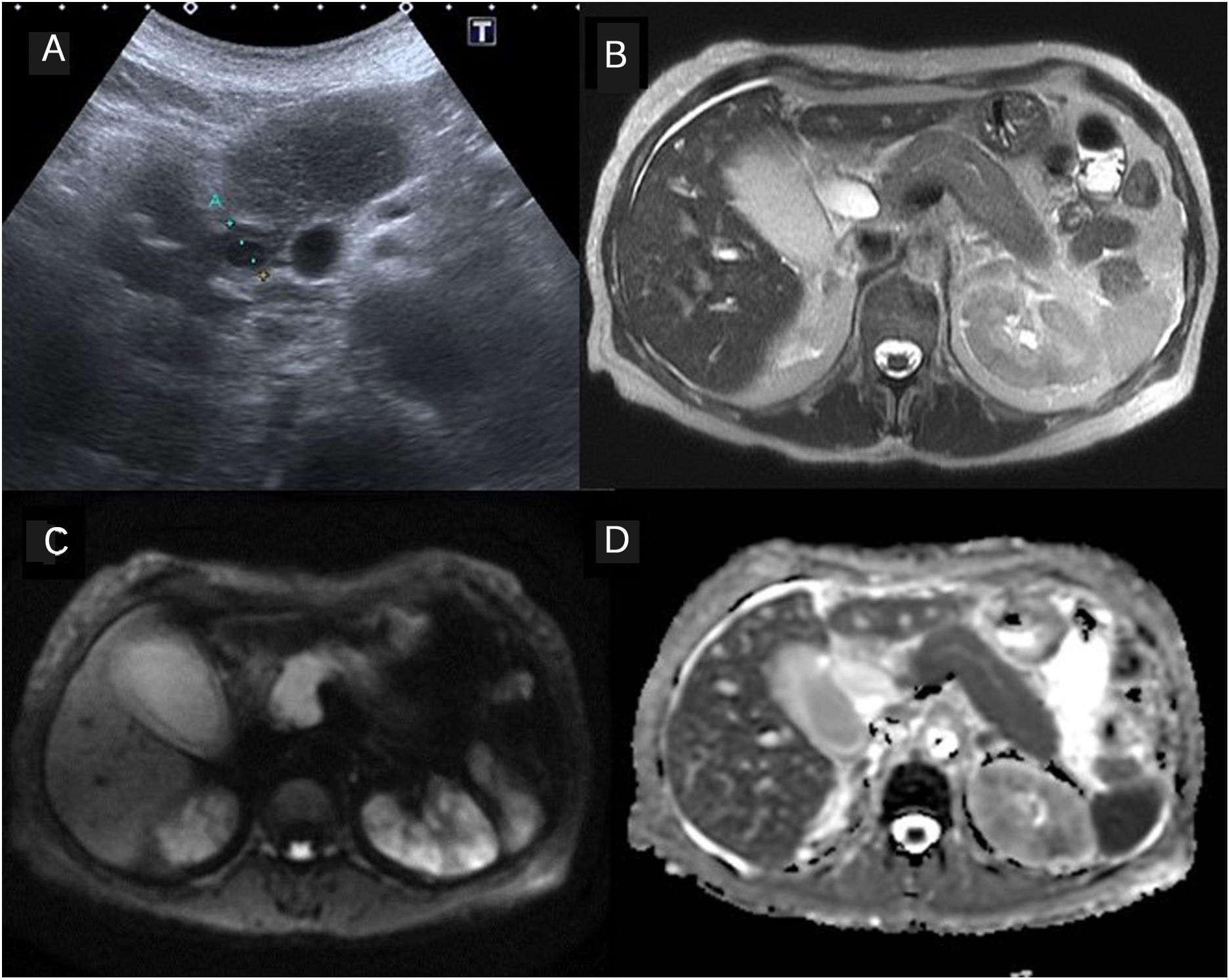

Imaging tests are not essential to the diagnosis of PBC and cholangiographic alterations are not usually observed Nevertheless, MRCP may be useful for distinguishing between PBC and other cholestatic diseases, mainly to rule out cholangitis secondary to biliary lithaisis or other secondary cholangitides, and the MR can also indicate the degree of fibrosis.27 Moreover, there are some imaging findings, such as the periportal collar sign, described by Wenzel as specific to PBC, consisting of numerous rounded lesions of between 5mm and 1cm with a low signal on T1-and T2-weighted sequences, focused in the portal vein branch, with no mass effect, and affecting any one of the hepatic lobes. This sign appears in 40% and is more prevalent in advanced stages.24,28–30 The presence of hypointense periportal collar is related to a significant degree of hepatic fibrosis27 (Fig. 7). Periportal hyperintensity on T2 sequences (cuffing) is a common, albeit non-specific sign, that is present from early stages and is indicative of active inflammation.

Primary biliary cholangitis. Periportal collar sign. Woman with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). The hypointense periportal collar (arrows), typical of PBC, is better appreciated in the T2-weighted images (A), although it can also be seen in diffusion-weighted images (B). Other unspecific signs are periportal oedema, small node cirrhosis, with “lace-like” enhancement pattern of the fibrotic bands (C: interstitial phase of the study with contrast), and adenopathies. The magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography was normal (not shown).

Another frequently observed finding is the presence of augmented nodes in the hepatic hilum, in the gastrohepatic ligament, or in the upper retroperitoneal space. In the more advanced stages of the disease, there may be signs of micronodular cirrhosis, splenomegaly, ascites, portosystemic collaterals (shunts) and portal thrombosis.30 Active inflammation of the portal triads may ultimately cause arterioportal shunts, identified as early enhancement areas on the MR.

The treatment of choice for patients with PBC is ursodeoxycholic acid. It improves cholestasis and symptoms, it delays disease progression with good long-term outcomes, and is also well tolerated by the patient.

Secondary chronic cholangitidesSome chronic cholangitides are caused by repeat or sustained damage to the bile ducts caused by different unknown aetiologies These are the most frequent ones.

Ischaemic cholangitisBiliary tree perfusion depends solely on arterial blood supply, meaning different aetiologies that affect the main hepatic arteries or the perbiliary plexus may cause an ischaemic cholangiopapthy. Most cases are iatrogenic, including vascular complications derived from liver transplant, embolisations, hepatic intra-arterial chemotherapy, or any bile duct surgery.6 Patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia or polyarteritis nodosa rarely present this type of cholangitis.1

The clinical and radiological findings are related to the extent of the ischaemic injury and the time of the disease. During the acute phase, symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, jaundice, and biliary sepsis. At this point, radiological tests can detect bile moulds or intraductal repletion defects and bilomas in the area close to the damaged bile duct.6 In the chronic phase, patients present cholestasis and radiological findings of multiple stenoses (non-anastomotic, normally affecting the hiliar region and the common hepatic duct) and bile duct dilations.1

Aetiological treatment of ischaemia may sometimes halt disease progression.

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitisRecurrent pyogenic cholangitis, formerly known as oriental cholangiohepatitis, due to its Asian provenance, is a progressive biliary disease characterized by recurring episodes of infectious cholangitis and pigmented intrahepatic lithiases. The initial biliary damage is probably secondary to a parasitic infection. Inflammatory stenoses and the presence of lithiasis produce recurrent biliary obstruction and cholangitis.6,31 Complications include liver abscesses, sepsis, portal thrombosis, pancreatitis, and cirrhosis. Epidemiological, clinical and radiological data are included for diagnostic purposes.

The MRCP shows intrahepatic biliary lithiases (Fig. 8), multiple intrahepatic bile duct stenoses, dilation of the central bile duct, and rapid sharpness of the proximal extrahepatic bile duct (“arrowhead” appearance). Pigmented intrahepatic calculi are normally hyperintense in T1 and better detected in T1 fat-saturated sequences. Involvement of the lateral segments of the left hepatic lobe and the posterior segments of the right hepatic lobe are more common, possibly leading to atrophy of these segments and to hypertrophy of the caudate and quadrate lobes, creating a rounded hepatic morphology.1,2 The diagnostic efficacy of MRCP is superior to that of ERPC in this entity.31

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis (oriental cholangiohepatitis). Asian patient with recurrent cholangitis. The coronal magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography images (A), T2-weighted (B), and T1 without contrast (C), show dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts, more on the left side, with major hypointense intrahepatic lithiases on T2 and hyperintense on T1. The T2-weighted (D) and baseline CT (E) axial MR images show large intrahepatic calculi.

Treatment normally includes the combination of antibiotics with interventions or surgical procedures for the extraction of the calculi and treating the stenosis to avoid biliary stasis and to prevent the recurrence of suppurative cholangitis and the formation of lithiasis.

HIV/AIDS-associated cholangiopathyHIV/AIDS-associated cholangiopathy is a disease that presents in patients with HIV infection and severe immunosuppression (CD4 values <100mm–3) and is currently very infrequent in countries where combined antiretroviral treatment is standard.32 Different pathogens have been associated with this disease, including Cytomegalovirus and Cryptosporidium.32 The diagnosis is made with the coexistence of background, clinical, analytical, and radiological data (particularly MRCP).

MRCP findings include intra- and extrahepatic alterations: papillary stenosis is found in up to 75% of patients (typically causing upper abdominal pain), frequently associated with multifocal intrahepatic stenoses (similar to those of PSC). One less frequent finding is the isolated stenosis of the extrahepatic bile duct in a segment of medium-large extension.3

Antiretroviral treatment and improvement of the immune system can halt or even reverse disease progression. Moreover, if the obstruction is persistent, interventions can be performed to alleviate symptoms.32

Portal biliopathyPortal biliopathy or portal cholangiopathy is an entity characterized by cholangiographic alterations in patients with portal cavernomatosis. Portal cavernomatosis consists of dilated and snake-like collaterals that appear in the hepatic hilum following portal thrombosis.33 The mass effect of the veins on the bile duct and secondary ischaemic changes can produce significant biliary stenoses.34

The radiological signs include portal thrombosis, portal vein collaterals (portal cavernomatosis) and bile duct dilation. These findings can be detected in the ultrasound or CT scan, although MRCP provides a better visualization of the bile duct and the vascular anatomy, which can help in determining the cause of the portal thrombosis33,35 (Fig. 9).

Portal biliopathy Patient with a record of splenectomy and chronic cholestasis. The magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (A) shows a reduction in the calibre of the right and left hepatic ducts in the hepatic hilar region with moderate proximal dilation of the intrahepatic ducts. The T2-weighted image (B) and the arterial (C) and venous (D) phases of the study with contrast show thrombosis of the principal portal vein with signs of cavernomatosis, which condition the extrinsic compression of the bile duct by venous collaterals.

Mirizzi syndrome is caused by the stenosis and obstruction of the common hepatic duct due to intrinsic compression of an impacted gallstone in the cystic duct or infundibulum; on some occasions a cholecysto-biliary fistula may be caused. It may condition recurring cholestases and cholangitides, as well as acute cholecystitis symptoms with biliary obstruction.

Radiological findings include the presence of gallstones, lithiasis in the cystic region, compression of the common hepatic duct with proximal dilation of the bile duct, and normal diameter of the distal common hepatic duct and of the common bile duct7 (Fig. 10). Treatment is surgical, although the operation is challenging, with a high risk of biliary duct lesion.

Mirizzi's syndrome Patient with cholestasis and mild jaundice. The thick-cut magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (A) shows dilation of the intrahepatic bile duct and stenosis of the common and left hepatic duct. Then T2-weighted coronal (B) and axial (C) plane images show a major lithiasis (arrow) impacted in the infundibulum as the cause of the bile duct compression.

Eosinophilic cholangitis is an infrequent disease characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the bile duct, as well as analytical eosinophilia in 50% of the cases, which helps to indicate a possible diagnosis.

Radiological findings include thickening of the common bile duct wall, the cystic duct, and the gallbladder, with diffuse or focal stenoses of the extrahepatic bile duct.6

This entity normally responds to treatment with corticosteroids and has a good prognosis.

Chronic cholangitides secondary to surgeryOne of the most frequent causes of chronic or recurrent cholangitis is as a secondary complication of hepatobiliary surgery. In surgical patients, cholangitis may be secondary to bile duct stenosis or the presence of enterobiliary reflux. It is important to know the surgery that was performed, since certain types of surgery characteristically present specific complications.

High-resolution images of the biliary anastomosis should be obtained, since most stenoses occur in this location. Defining the exact location and length of the stenosis will be critical in choosing the best treatment option, which may consist of radiological, endoscopic, or surgical interventions.

Magnetic resonance, with different sequences and acquisition planes, is usually the best imaging technique for the diagnosis of alterations in an operated biliary duct and for detecting associated findings such as lithiases, although in some patients the MRCP may be low-quality due to the presence of aerobilia or metal artefacts. In these patients, the performance of a CT scan or even a direct cholangiography with contrast can be used as an alternative to provide a better visualization of the bile duct and its anastomoses.

ConclusionsThe chronic cholangitides include highly diverse diseases in terms of aetiologies and treatment possibilities.

MRCP is the best non-invasive imaging technique for the evaluation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile duct. The use of an optimized and adapted protocol is necessary to be able to obtain high-quality studies. The MR protocol should frequently include a complete evaluation of the liver.

In a patient with chronic cholestasis and suspected PSC, MRCP is the diagnostic technique of choice to demonstrate bile duct alterations. Patients with IgG4-associated cholangitis and chronic secondary cholangitides may also presents stenoses and dilations of the intra- and extrahepatic bile duct on the cholangiography.

The clinical and analytical context is essential to the differential diagnosis of chronic cholangitides; nevertheless, in many cases, radiological findings can help to diagnose these diseases, assess complications or rule out the presence of a neoplasm.

Authors- 1.

Responsible for study integrity: ECC, JLH, RMF.

- 2.

Study conception: ECC, JLH, RMF.

- 3.

Study design: ECC, JLH, RMF.

- 4.

Data acquisition: NA.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: NA.

- 6.

Statistical processing: NA.

- 7.

Literature search: ECC, JLH, RMF.

- 8.

Drafting of the manuscript: ECC, JLH, RMF.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: RMF.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: ECC, JLH, RMF.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Cebada Chaparro E, Lloret del Hoyo J, Méndez Fernández R. Colangitis crónicas: diagnóstico diferencial y papel de la resonancia magnética. Radiología. 2020;62:452–463.