Complications after abdominal surgery are often seen in emergency departments. Many postoperative complications (e.g., infections, abscesses, hematomas, and active bleeding) are common to all types of surgery; others are specific to different types of surgery. Computed tomography (CT) is the technique normally used to diagnose postoperative complications.

This article reviews the changes that occur after some of the most common abdominal interventions that can be mistaken for pathological processes, the findings that can be considered normal after surgical intervention, and the most common early complications. It also describes the optimal protocols for CT studies depending on the different types of complications that are suspected.

La complicación tras la cirugía abdominal es un hecho frecuente en los servicios de urgencias. Muchas complicaciones son comunes a todos los tipos de cirugía, incluyendo infecciones, abscesos, hematomas, sangrado activo, mientras que otras son específicas del tipo de cirugía realizada. La tomografía computarizada (TC) es la técnica de estudio normalmente empleada para su diagnóstico.

En este trabajo revisaremos los cambios que se producen en algunas de las intervenciones abdominales más frecuentemente realizadas y que pueden confundirse con procesos patológicos, los hallazgos que pueden considerarse normales tras la intervención quirúrgica y las complicaciones tempranas más frecuentes. También describiremos el protocolo óptimo de realización de la TC según el tipo de complicación que se sospeche.

Complications of abdominal surgery are a very broad subject area. This article focuses on the most common surgical interventions in the gastrointestinal and biliopancreatic area,1 where we review the expected surgical changes after each of the interventions described and their differentiation with pathological findings.

Surgical procedures and anatomical changesBariatric surgeryLaparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypassThe stomach is divided into a small upper pouch (15−20 ml) and a much larger excluded part. The Roux jejunal limb (efferent loop) is attached to the upper pouch by a gastrojejunal anastomosis. The remaining stomach is left in place and is attached via the afferent (biliopancreatic) limb to the distal jejunum with a jejunojejunal anastomosis (Fig. 1).

The excluded stomach and afferent limb should not be filled with oral contrast; they may be filled with fluid or gas and should not be confused with abscesses.2

If the Roux loop has a retrocolic course, a discreet fixed stenosis of the lumen can be observed in its middle segment; this is due to its passage through the mesocolon, and should not be misinterpreted as a pathological stenosis.

Laparoscopic sleeve or vertical sleeve gastrectomyThe stomach is resected along the greater curvature from the fundus to the proximal antrum, leaving a tubular remnant which includes the pylorus and cardia. It has a residual volume of approximately 100 ml (Fig. 1).

The postoperative appearance of the gastric sleeve is highly variable: tubular pattern (66%, most common); upper pouch; lower pouch; upper-lower pouch; pseudodiverticular pattern; and even corkscrew appearance.

It is important to know that small upper pouches can mimic extraluminal contrast, leading to a misdiagnosis of leakage.3

PancreaticoduodenectomyThere are two variants of pancreatoduodenectomy (PD): the classic Whipple procedure and the pylorus-sparing procedure. Both include resection of the head of the pancreas, the duodenum, gallbladder, distal bile duct and jejunum, with creation of a hepaticojejunostomy and a pancreaticojejunostomy.

In the Whipple procedure, the gastric antrum is removed by creating a gastrojejunostomy, while the pylorus-sparing variant preserves the gastric antrum and the first portion of the duodenum by creating a duodenojejunostomy.4,5

The most common normal postoperative findings are pneumobilia, perivascular cuffing, lymphadenopathy, acute anastomotic oedema, small fluid collections and peripancreatic or mesenteric fat stranding.4,5

The perivascular cuffing is a soft tissue density that surrounds the coeliac trunk and its branches, and the superior mesenteric artery. It is due to an inflammatory reaction. It may have a focal or nodular appearance, which should not be confused with residual disease or local recurrence. It usually disappears within two to three months.4

Dilation of the pancreatic duct or mild intrahepatic bile duct dilation caused by oedema of the anastomosis is common, and should not be misinterpreted as a biliary-enteric stricture.

In certain circumstances, a stent is placed in the main pancreatic duct, which is seen as a hyperdense linear image traversing the pancreatic duct into the jejunum. It is used to reduce the risk of pancreatic fistula and should not be confused with a foreign body or a suture line.5

All these changes tend to return to normal over the first two months.

Bowel surgeryThe absence of the resected bowel segment, the surgical anastomosis and displacement of the adjacent viscera into the resected space will be observed in imaging studies.5 It is particularly important to be familiar with the postoperative changes in the rectum, as they can be confused with abscesses and tumour recurrence.

In a lower abdominal resection, we will see the colorectal anastomosis and an increase in the presacral space, with the rectum separated from the sacrum by about 2 cm. It is common to find small fluid collections or an image of soft tissue density in the presacral area. An increase in these findings in follow-up scans should lead us to suspect an anastomotic leak or tumour recurrence.6,7

In abdominoperineal resection, the sigmoid colon, rectum, anal canal and anal sphincters are resected through one incision in the anterior abdominal wall and another in the perineum. Intestinal transit is reconstructed with a permanent colostomy in the left iliac fossa. This causes posterior displacement of the pelvic urogenital structures and small bowel loops into a precoccygeal location. It is common to find a presacral mass, which represents granulation tissue or postoperative fibrosis. It may not be possible to distinguish such masses from tumour recurrence, but changes in subsequent follow-up scans will help make the distinction.6,7

CholecystectomyWe will see the absence of the gallbladder in the bed along with the artery ligation clips and the cystic duct.

Within the postoperative period, it is common to find small amounts of fluid in the surgical bed, and this can be considered normal during the first three to five days.8 If these findings progress, they may indicate a bile leak.

The haemostatic material (for example, Surgicel®, Spongostan®) in the gallbladder bed produces an image of fluid density with multiple air bubbles inside, which can simulate an abscess or haematoma. Retained surgical material (gossypiboma) has a similar appearance, but such material can be differentiated by its radiopaque marker.

It is common to find some non-obstructive dilation of the bile duct, a finding which will have to be correlated with clinical and analytical data.

Normal postoperative findingsIt is important to know the chronology of the most common postoperative findings in order not to confuse them with complications.

Subcutaneous emphysema. More common with laparoscopic surgery. It usually disappears within seven days of surgery. It is important not to confuse it with necrotising fasciitis, which is a surgical emergency. The incidence of necrotising fasciitis is very low, usually manifests later and is typically associated with peri-incisional erythema, foul-smelling drainage from the wound, fever and pain.9

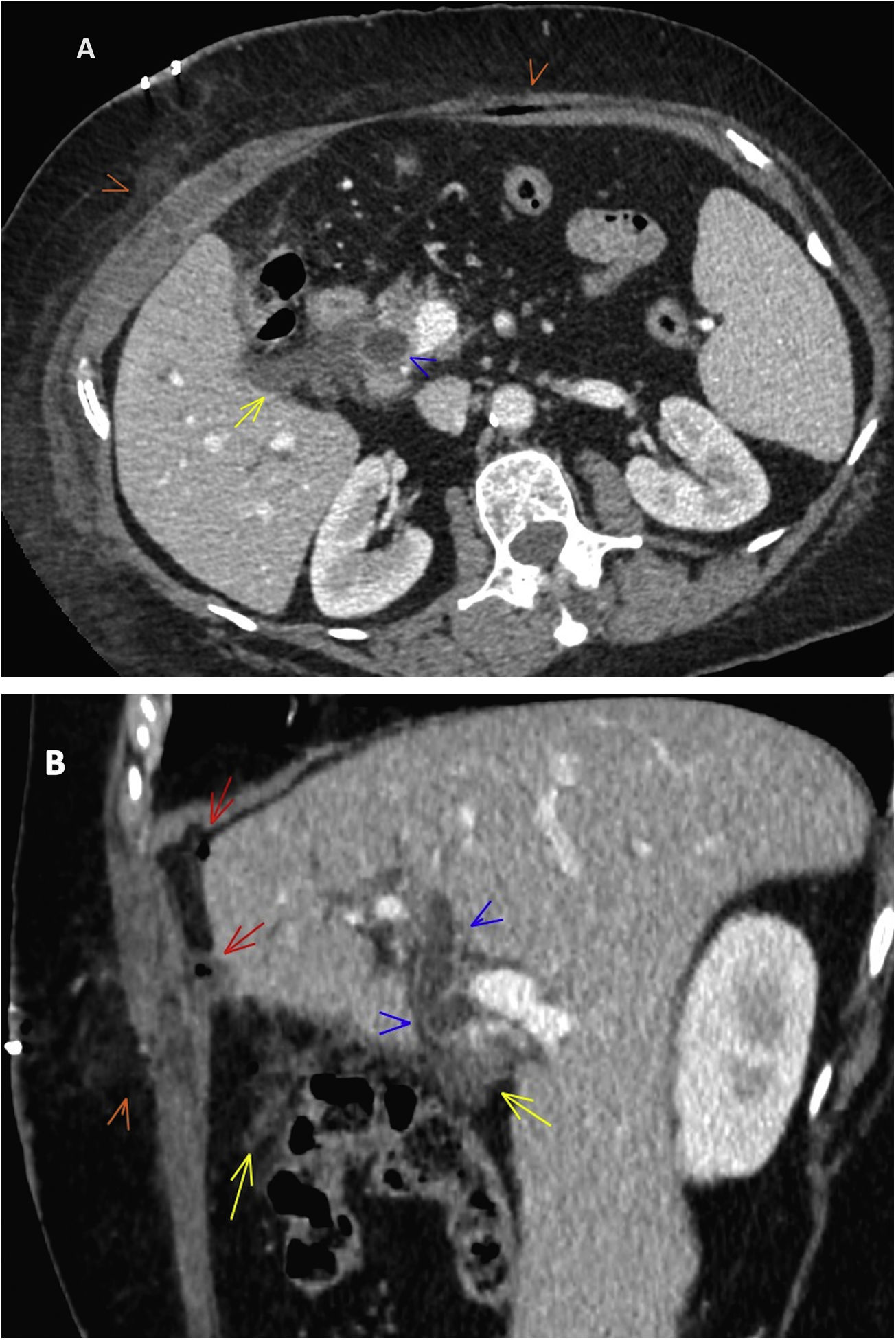

Alteration in fat density and small, non-encapsulated, crescent-shaped fluid collections, which resolve spontaneously (Fig. 2).

Normal post-cholecystectomy findings. CT of abdomen with IV contrast. (A) Axial plane. (B) Sagittal reconstruction: small haematoma and some air bubbles in the musculature of the abdominal wall with fat infiltration of the subcutaneous cellular tissue (orange arrowheads); change in fat density with a small non-encapsulated fluid collection in the surgical bed (yellow arrows); small bubbles of pneumoperitoneum (red arrows). Non-obstructive dilation of the common bile duct (blue arrowhead).

Pneumoperitoneum. May represent residual air or be indicative of a complication such as leakage from the anastomosis or perforation of the hollow viscus that requires urgent surgical intervention (Fig. 2).

"Normal" pneumoperitoneum resolves in most cases within a week, but may last from 10 to 24 days.10,11

The management of postoperative pneumoperitoneum will depend on the patient's symptoms, physical examination and laboratory test results. Clinical findings suggesting peritonitis, haemodynamic instability or sepsis are indications for emergency surgery. Isolated pneumoperitoneum only requires surveillance, but associated free fluid should make us suspect a complication.

Postoperative ileus. This usually manifests as a generalised distension of intestinal loops, both in the small bowel and the large bowel, without a transition point and with the presence of air in the rectum. It is considered a normal phenomenon in the first three or four days after abdominal surgery (up to five days in colon surgery), as the body's physiological response to external aggression.12

Postoperative complicationsComputed tomography (CT) is the technique normally used to investigate postoperative complications. The standard scan of the abdomen is performed from the base of the thorax to the pubic symphysis, with non-iodinated intravenous (IV) contrast, in venous phase (70−80 s). However, the study protocol may vary depending on the suspected diagnosis.

General complicationsAbdominal wall complicationsInfectionInfection in the surgical wound is common. It is not usually an indication for an imaging test, unless an underlying abscess or an abscess in the abdominal cavity is suspected.

Cellulitis can be seen as thickening of the skin, subcutaneous fat stranding and thickening of the adjacent superficial fascia.

Abscesses show up as low-density collections with peripheral enhancement, with or without air inside them, and inflammatory changes in the adjacent subcutaneous tissue.13

The differential diagnosis usually includes seromas, which are fluid collections that gradually resolve over the first couple of weeks after surgery.14

HaematomaA small incisional haematoma is common. However, this may develop into a significant rectus sheath haematoma as a result of coagulation issues or due to injury to the epigastric vessels during abdominal incision or trocar insertion.14

Evisceration/eventrationEvisceration or acute dehiscence of the wall occurs due to a failure of effective healing. When it is total (complete evisceration), all planes of the abdominal wall are affected and abdominal viscera may come out.15

The main clinical manifestations are the leakage of serosanguineous fluid (blood-tinged exudate), adynamic ileus and swelling of the surgical wound. Treatment involves emergency surgery with closure of the wall.16

Evisceration is partial when there is no separation of the skin plane and, barring exceptions, the patient can be stabilised before repairing the abdominal wall.15

Eventration or incisional hernia is the progressive distension of a wound scar after laparotomy, and less frequently after laparoscopy, in which the skin and subcutaneous cellular tissue are intact. It is a late complication of abdominal surgery.

Abdominal cavity infection: abscess/peritonitisThese essentially occur for two reasons: microbial contamination during the surgical intervention or wound dehiscence. They may also be secondary to an abdominal wall infection, fistulae and perforation. Contamination of the peritoneum leads to the development of inflammatory collections, localised abscesses or generalised peritonitis.14

The findings in peritonitis are ascites, increased mesenteric fat attenuation and focal or diffuse thickening of the peritoneum, which shows increased contrast uptake. Associated collections and paralytic ileus reactive to neighbouring inflammatory changes may also be identified, as well as pneumoperitoneum in cases of perforation or wound dehiscence.17

Ileus/bowel obstructionPostoperative ileus is considered a physiological response to the surgical procedure. An interval of between two and seven days is considered normal for the resumption of intestinal transit after surgery.18

When the symptoms persist over time, this is considered a paralytic ileus, also known as pathological or prolonged ileus, and it must be differentiated from secondary ileus, which is linked to extrinsic causes such as abscesses or peritonitis.

CT is helpful in differentiating between paralytic ileus and bowel obstruction.19 Moderate, generalised dilation of the colon and small bowel loops, with no transition zone, is more suggestive of paralytic ileus.

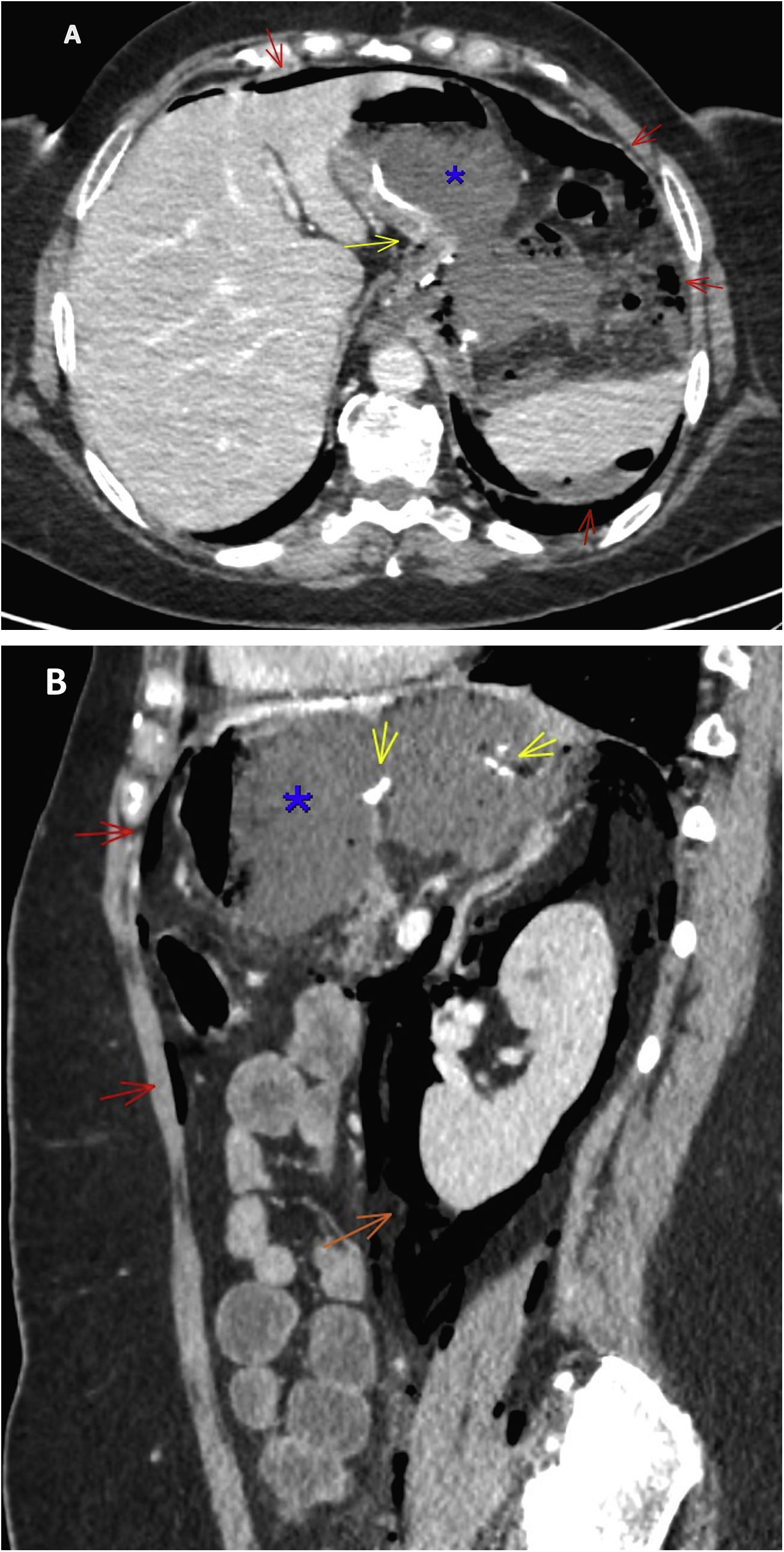

Bowel obstruction (BO) in the early postoperative period (first 30 days after the operation) is rare; 90% of these obstructions are caused by adhesions, generally due to peritonitis (Fig. 3).19 They may also be associated with internal hernias due to omental or mesenteric defects resulting from the procedure.

Bowel obstruction after cholecystectomy. CT of abdomen with IV contrast. (A) Axial plane. (B) Coronal reconstruction. Fluid accumulation in the cholecystectomy surgical bed, the lesser sac and the right subphrenic region (blue asterisk); bowel obstruction: dilated small bowel loops (yellow arrow) with a change in lumen at the level of the distal ileum in the right iliac fossa (red arrow). Significant gastric distension with contents (orange cross).

The most important radiological sign for diagnosing BO is the sudden transition from a dilated to non-dilated bowel, which indicates the point of obstruction. The dilated loops have a diameter greater than 2.5 cm. The faeces sign may also be seen proximal to the point of obstruction, as well as the absence of gas in the colon and rectum.

Vascular complicationsIf a vascular complication is suspected, a CT should be performed with baseline phases (allows differentiation of sutures, clips, post-surgical staples and calcifications from a possible extravasation of the contrast indicating active bleeding), followed by the arterial and portal venous phases. In active arterial bleeding, extravasation of IV contrast into the haematoma is seen in the arterial phase and usually increases in the portal phase.

Haemorrhagic complications are the result of incomplete haemostasis or bleeding diathesis. They can manifest as haematomas or haemoperitoneum, with or without active bleeding, pseudoaneurysms and, far less frequently (0.5–1%), as gastrointestinal haemorrhage due to bleeding at the site of the anastomosis.12 Other less common vascular complications are thrombosis and visceral infarction.

Haematomas are identified on non-contrast CT as high-attenuation collections; from 45 to 70 HU in the acute haematoma with clot, and from 30 to 45 HU in the surrounding areas of acute haemorrhage without clots or chronic haemorrhage.

Identification of the haematoma in the surgical bed or adjacent to the anastomosis, also known as the sentinel clot sign, is a useful finding on CT for locating the source of bleeding.20

Another vascular complication is a pseudoaneurysm, a rounded lesion that has the same density as the adjacent artery, both in the arterial and portal phases (Fig. 4).

Pseudoaneurysm of the splenic artery after sleeve gastrectomy. CT of abdomen with IV contrast in axial planes. (A) Arterial phase. (B) Venous phase. (C) Intraoperative image. Rounded image with the same density as the splenic artery, on which it depends, and without alteration of its morphology in the arterial or venous phase (red arrows), and its correlation with the surgery (yellow arrow). Perihepatic and perisplenic haemoperitoneum (density in HU in blue).

This occurs in 1–5% of cases after upper gastrointestinal operations and in 5–10% of resections of the inferior rectus femoris.14

Anastomotic dehiscence (AD) is defined as the loss of continuity of the anastomosis with leakage of the intraluminal contents to the outside.

The main signs of leakage are large collections of air and fluid (hydropneumoperitoneum) or abscess in the surgical bed (Fig. 5).21

Dehiscence of the anastomosis after sleeve gastrectomy. CT of abdomen with IV contrast. (A) Axial plane. (B) Sagittal reconstruction. Biloculated collection adjacent to the anastomosis, with liquid and air content forming an air-fluid level (blue asterisk). Extensive pneumoperitoneum (red arrows) and pneumoretroperitoneum (orange arrow). The yellow arrows point to the sutures and the tubular remnant of the stomach.

Although extravasation of oral or rectal contrast is the most specific sign of anastomotic leak, routine use of contrast is not usually necessary. It is used in some specific cases to try to demonstrate small anastomotic leaks. Sodium amidotrizoate (Gastrografín®) diluted to 3–5% is usually used. In the case of clinically visible leaks or those with signs of sepsis or peritonitis, an urgent repeat laparotomy is indicated. The diagnostic challenge lies in identifying the anastomotic leak in the early postoperative period and in cases with mild or nonspecific symptoms.

Patients with and without anastomotic leaks had similar findings in the early postoperative period (small reactive fluid collections and pneumoperitoneum). This means limited diagnostic accuracy of anastomotic leaks in the early days of the postoperative period.21 It is vital to compare CT findings with clinical data and laboratory results. In patients with anastomotic leaks, peri-anastomotic air and fluid is increased on the repeat CT scans.

It is important to differentiate between AD and a fistula. A fistula is a communication between adjacent organs or to the external environment by way of an epithelialised tract, which generally takes from eight to 30 days to form.22

Vascular complicationsIn the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, acute ischaemia of the Roux loop can occur due to vascular compromise causing mobilisation of the jejunum. CT usually shows wall thickening in the jejunal loop, stranding of adjacent fat and engorgement of the mesenteric vessels.2

Splenic infarction is a rare complication of sleeve gastrectomy, due to ligation of the short gastric vessels (branches of the splenic vessels) when releasing the greater gastric curvature. It is usually asymptomatic, small in size and located in the upper pole.3

Complications of pancreaticoduodenectomyPancreatic fistulaThis is the most common complication (10–30%).4 It is defined as the leakage of pancreatic secretions with an amylase level in the drainage fluid three times higher than the serum amylase, after postoperative day three.

Indicative CT findings include: fluid collections around the pancreaticojejunostomy site or in the pancreatic bed; air bubbles in a peripancreatic collection; and rupture of the pancreatic anastomosis.

Bile leakBile leaks are relatively rare (1–5%).4 They are defined as a bilirubin concentration in the drainage fluid three times higher than the serum bilirubin level from postoperative day three.

On CT, it manifests as a focal fluid collection near the bilioenteric anastomosis. Because of the proximity to the pancreatic anastomosis, differential diagnosis based on CT findings alone is virtually impossible.

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with liver-specific contrast can confirm bile leaks.4,5

Vascular complicationsBleeding after pancreaticoduodenectomy is rare. Early bleeding (<24 h), caused by inadequate ligation of the stump of the gastroduodenal artery (GDA), is distinguished from late bleeding (>5 days), associated with dehiscence of the anastomosis and vascular erosion in the form of a pseudoaneurysm of the GDA.

Thrombosis of the superior mesenteric vein or portal vein may also occur, which may be complicated by intestinal ischaemia or hepatic ischaemia.

Another much rarer complication is liver infarct, the result of injury or thrombosis of the hepatic or coeliac artery, which can progress with biliary necrosis, liver superinfection and liver abscesses.5

Complications of cholecystectomyBiliary complications are usually related to inadvertent injury to the biliary tree that can cause bile leaks (in the early period) or stricture, due to reparative fibrosis and secondary dilation of the duct (late complications).23

Bile leaksThis is one of the most common biliary complications. Bile extravasation generally occurs in the surgical bed and in the subhepatic region.8

The symptoms are abdominal pain, sepsis and jaundice. A bile leak is suspected when there is high output from the biliary drainage and free fluid in the cholecystectomy surgical bed.

When the collection of bile is encapsulated, it is called a biloma and appears as a well defined fluid collection. It can be loculated or multiloculated. It is usually close to the site of the leak, but can occasionally be remote or even intrahepatic.24

Biliary peritonitisThis is a serious complication of hepatobiliary tract surgery, with a mortality rate of about 50%. It occurs when bile leakage is too rapid and is not contained in the subhepatic space due to peritoneal adhesions. CT usually shows large, relatively low-attenuation ascites.

In some cases the abdominal cavity has a great tolerance for bile, and significant amounts can be there for days or weeks with minimal symptoms and only slight lab test abnormalities. This clinical situation is known as biliary ascites, while biliary peritonitis is an acute condition with numerous abdominal symptoms.25

Radiological confirmation of bile leakage, if necessary, can be established by hepatobiliary scintigraphy or MRI with liver-specific contrast. In some cases, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography can help identify the lesion.25

ConclusionIt is important to recognise the anatomical changes that occur after abdominal surgery and the normal postoperative findings in order not to confuse them with pathological findings. CT is very useful in the diagnosis of postoperative complications. It is less helpful in the early postoperative days, when it is essential to correlate with clinical and lab test data.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for the integrity of the study: ARD and DAM-R.

- 2

Study conception: ARD and DAM-R.

- 3

Study design: ARD and DAM-R.

- 4

Data collection: ARD and DAM-R.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: ARD and DAM-R.

- 6

Statistical processing: not applicable.

- 7

Literature search: ARD and DAM-R.

- 8

Drafting of the article: ARD and DAM-R.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: ARD and DAM-R.

- 10

Approval of the final version: ARD and DAM-R.

The authors declare that they have not received any funding for this paper.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.