Although small-bowel wall thickening is a common manifestation of Crohn’s disease and tumors, many other entities can give rise to similar imaging findings. The small bowel is difficult to access by endoscopy, so radiologic imaging tests play an essential role in the diagnosis of conditions involving the small bowel. The main objectives of this paper are to explain the definition of small-bowel wall thickening, analyze the patterns of involvement seen in multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) with intravenous contrast administration, and provide an image-based review of the different causes of small-bowel wall thickening. The differential diagnosis must include many entities because wall thickening can result from immune-mediated, infectious, or vascular causes, as well as from toxicity and other lesser-known entities. As the imaging appearance of many of these conditions overlap, clinical and laboratory findings are necessary to support the imaging diagnosis.

El engrosamiento parietal del intestino delgado es una manifestación frecuente en la enfermedad de Crohn y en las neoplasias, aunque muchas otras entidades pueden presentar hallazgos de imagen similares. El intestino delgado es poco accesible mediante el examen endoscópico, por lo que las pruebas de imagen radiológicas tienen un papel esencial en el diagnóstico. En este trabajo, nuestros objetivos principales fueron explicar la definición de engrosamiento del intestino delgado, estudiar los patrones de afectación en la tomografía computarizada multidetector (TCMD) con contraste intravenoso (CIV) y proporcionar una revisión, basada en imágenes, de las diferentes causas de engrosamiento de intestino delgado. El diagnóstico diferencial es amplio y complicado, ya que existen causas inmunomediadas, infecciosas y vasculares, casos de toxicidad y otras entidades más desconocidas. Como la apariencia radiológica de muchas de estas enfermedades puede superponerse, se necesitan datos clínicos y analíticos para apoyar nuestro diagnóstico.

The small bowel is more difficult to access by endoscopy than the oesophagus, the stomach and the large bowel, so radiological imaging tests play an essential role in assessing this region.1,2 Many different conditions can lead to small bowel wall thickening, the most common of which are inflammatory bowel disease and neoplasms.3–7 The objectives of this review article were to review the definitions and enhancement patterns of wall thickening on multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) with intravenous contrast (IVC) and to provide an image-based review of the various causes.

When assessing small bowel wall thickening by MDCT, we need to measure parameters such as the degree of wall thickening, the length of involvement, the symmetry or asymmetry, and wall enhancement. It is important to note that the thickening varies depending on the distension of the loops. As a general rule, the small bowel wall is considered to be thickened if it measures more than 3 mm.1,3 The length of involvement is another parameter to assess when wall thickening is detected on MDCT. Thickening is considered as focal when affecting a segment of less than 5 cm; segmental from 6 to 40 cm, and diffuse when more than 40 cm.1,3,6 Symmetric or concentric thickening is when the degree of increased thickness is the same in the entire circumference of the affected segment of small bowel wall. Asymmetric involvement is characterised by different degrees of eccentric wall thickening.3,6 In terms of wall enhancement, after intravenous administration of contrast and acquisition of images in the portal phase, the bowel wall shows contrast uptake. The most intense enhancement is seen in the mucosal layer, which can be clearly differentiated from the other layers. The submucosa is less vascular and is rarely seen as an independent structure on MDCT images, unless it is oedematous, fat infiltrated or haemorrhagic. The muscularis propria and serosa also show enhancement, but it is less obvious than that of the mucosa. There are several patterns of bowel wall enhancement. Stratification, also known as the "double halo" sign or "target" sign, consists of alternating densities in the bowel wall layers (hyperenhancement of the mucosa and oedema/fatty infiltration of the submucosa and uptake in the serosa). Within this pattern, we have to specify the density that predominates in the submucosa (water or fat). The white enhancement pattern shows intense contrast uptake by the entire wall, with the density being equal to or greater than that of the vessels. The grey pattern is characterised by reduced wall enhancement with a density similar to that of muscle. Last of all is the pattern of pneumatosis intestinalis, with intramural bowel gas.1,3,6

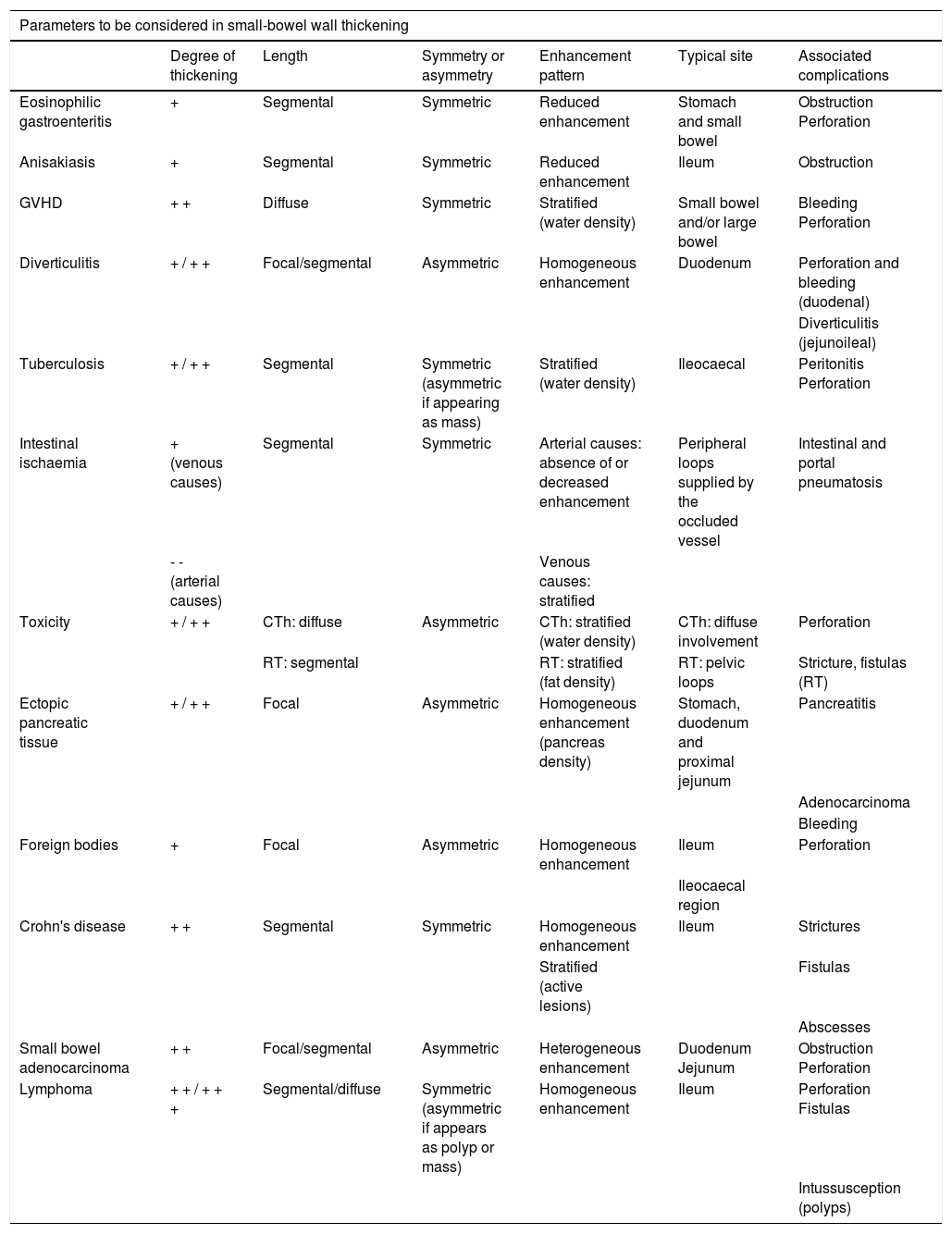

Summary table.

| Parameters to be considered in small-bowel wall thickening | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of thickening | Length | Symmetry or asymmetry | Enhancement pattern | Typical site | Associated complications | |

| Eosinophilic gastroenteritis | + | Segmental | Symmetric | Reduced enhancement | Stomach and small bowel | Obstruction Perforation |

| Anisakiasis | + | Segmental | Symmetric | Reduced enhancement | Ileum | Obstruction |

| GVHD | + + | Diffuse | Symmetric | Stratified (water density) | Small bowel and/or large bowel | Bleeding Perforation |

| Diverticulitis | + / + + | Focal/segmental | Asymmetric | Homogeneous enhancement | Duodenum | Perforation and bleeding (duodenal) |

| Diverticulitis (jejunoileal) | ||||||

| Tuberculosis | + / + + | Segmental | Symmetric (asymmetric if appearing as mass) | Stratified (water density) | Ileocaecal | Peritonitis Perforation |

| Intestinal ischaemia | + (venous causes) | Segmental | Symmetric | Arterial causes: absence of or decreased enhancement | Peripheral loops supplied by the occluded vessel | Intestinal and portal pneumatosis |

| - - (arterial causes) | Venous causes: stratified | |||||

| Toxicity | + / + + | CTh: diffuse | Asymmetric | CTh: stratified (water density) | CTh: diffuse involvement | Perforation |

| RT: segmental | RT: stratified (fat density) | RT: pelvic loops | Stricture, fistulas (RT) | |||

| Ectopic pancreatic tissue | + / + + | Focal | Asymmetric | Homogeneous enhancement (pancreas density) | Stomach, duodenum and proximal jejunum | Pancreatitis |

| Adenocarcinoma | ||||||

| Bleeding | ||||||

| Foreign bodies | + | Focal | Asymmetric | Homogeneous enhancement | Ileum | Perforation |

| Ileocaecal region | ||||||

| Crohn's disease | + + | Segmental | Symmetric | Homogeneous enhancement | Ileum | Strictures |

| Stratified (active lesions) | Fistulas | |||||

| Abscesses | ||||||

| Small bowel adenocarcinoma | + + | Focal/segmental | Asymmetric | Heterogeneous enhancement | Duodenum Jejunum | Obstruction Perforation |

| Lymphoma | + + / + + + | Segmental/diffuse | Symmetric (asymmetric if appears as polyp or mass) | Homogeneous enhancement | Ileum | Perforation Fistulas |

| Intussusception (polyps) | ||||||

GVHD, graft versus host disease; CTh: chemotherapy; RT: radiotherapy.

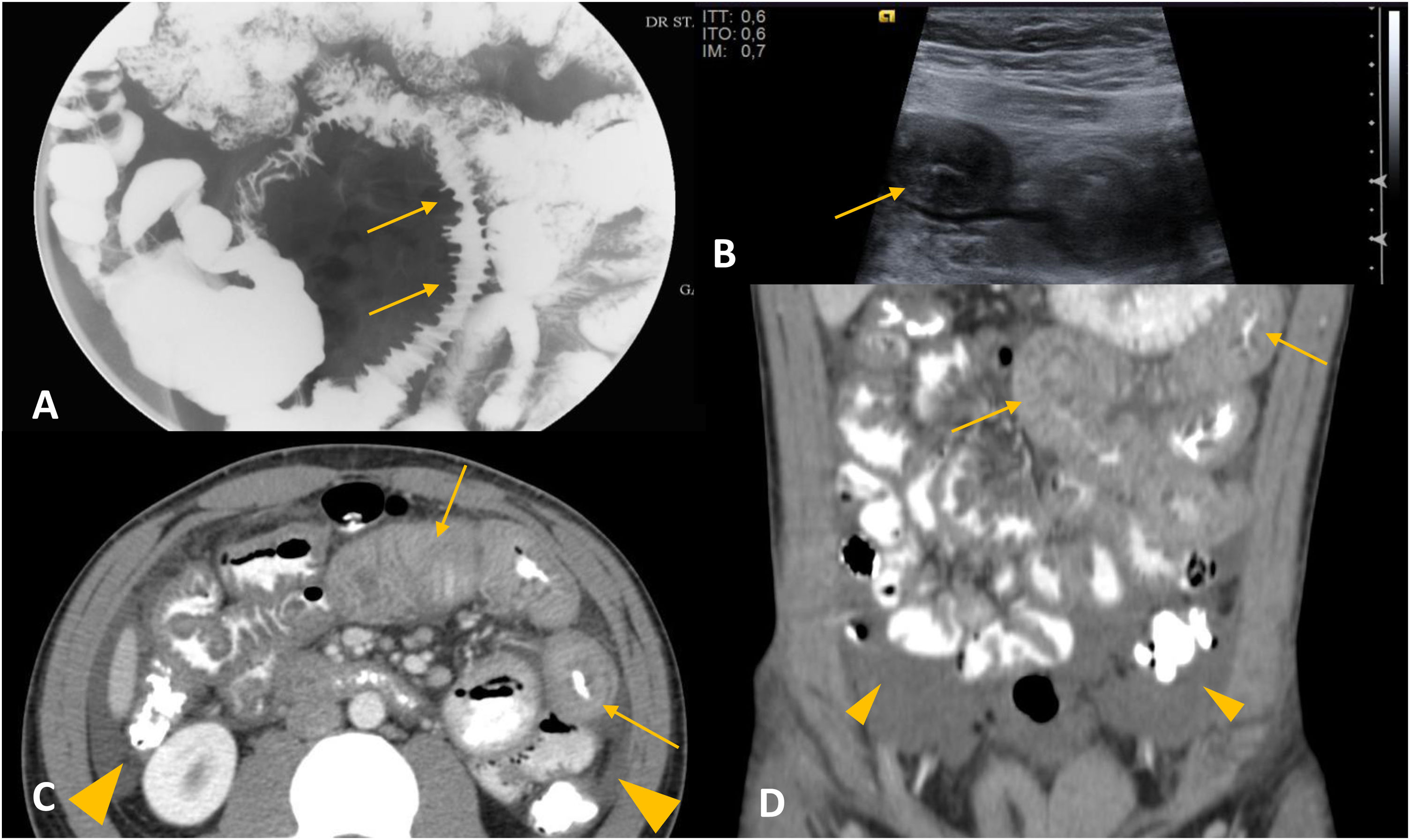

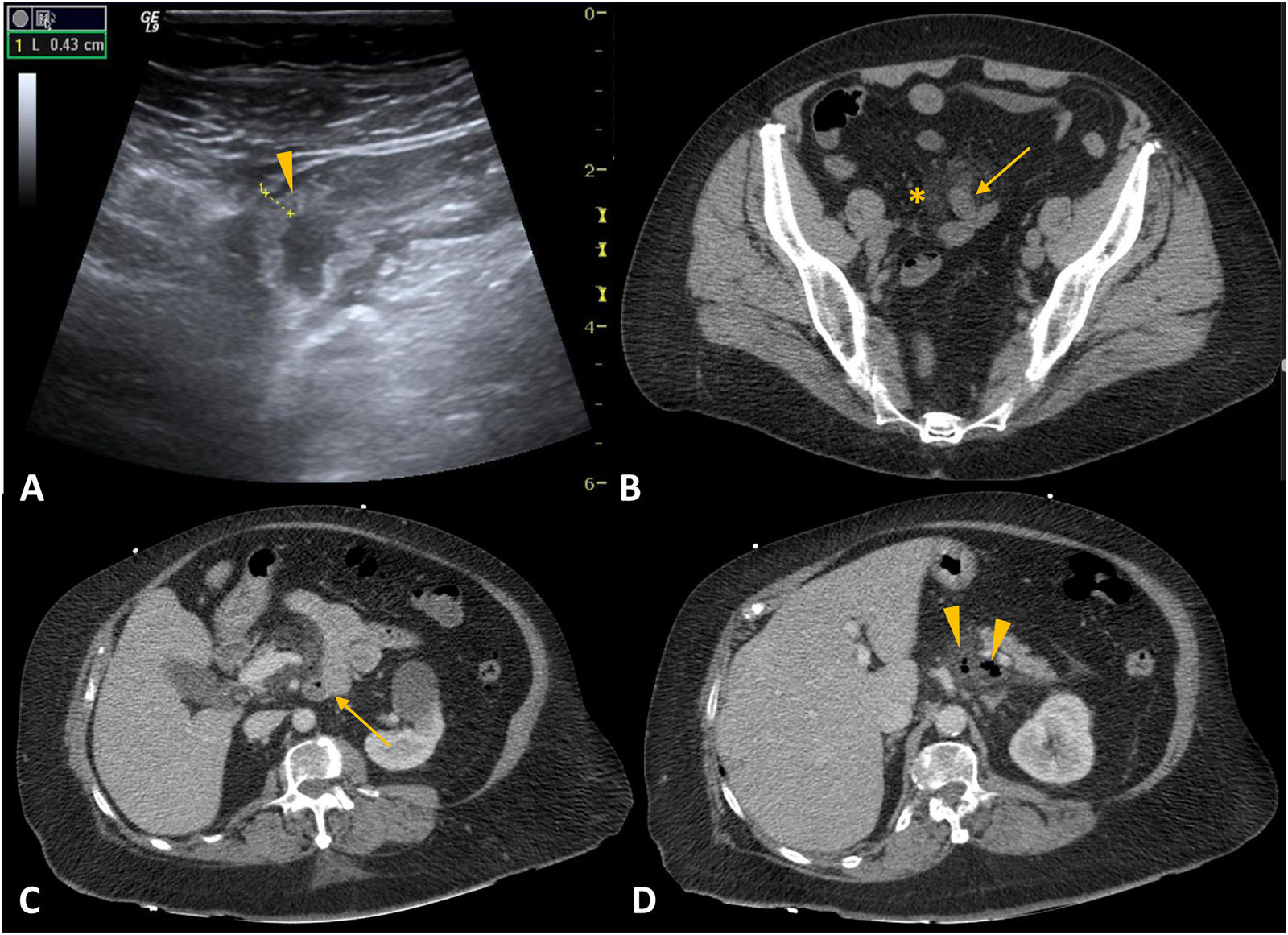

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is a rare disease, characterised by infiltration of the gastrointestinal tract by eosinophils, with no evidence of other secondary causes. Its prevalence in Spain is 44 cases per 100,000 population.8 It occurs most commonly from the third to fifth decades of life and predominantly affects males. Patients typically have a history of atopy.9,10 The manifestations of the disorder not only depend on the specific site, but also the specific layer of the gastrointestinal tract involved. Any part of the tract can be affected, but the most common sites are the stomach and the small bowel.3 The most common symptoms are abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Patients may also experience dysphagia, food impaction and diarrhoea, and even growth retardation in severely affected children. On MDCT with IVC, small bowel thickening would be segmental or diffuse and symmetrical, with oedema of the submucosa and decreased wall enhancement. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis with a predominance of mucosal layer involvement causes thickening of the intestinal folds, polyps, and ulcers (Fig. 1). When the muscle layer is involved, it is common to detect small-bowel wall thickening, which can cause stricturing and, consequently, lead to bowel obstruction (Fig. 1). Lastly, the presence of ascites, lymphadenopathy, peritoneal thickening and clustering of small bowel loops are characteristic of the serosal type.3,9,10 Radiological findings are very helpful for the diagnosis, as almost half of endoscopic studies do not show relevant findings. In the differential diagnosis, infections by other intestinal parasites that can simulate the same clinical, analytical and imaging findings should be considered. Corticosteroids are the main treatment.9,10

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. A) Barium study. B) B-mode ultrasound. C and D) Axial (C) and coronal (D) slices of computed tomography with administration of intravenous contrast and oral contrast. A 34-year-old female patient with fever, vomiting and diffuse abdominal pain. In image A, there is a thickening of the folds of a jejunum segment (arrows). The images show oedema of the submucosa and symmetrical, segmental thickening of the jejunum wall (arrows in B-D). Small amount of free fluid (arrow heads in C and D).

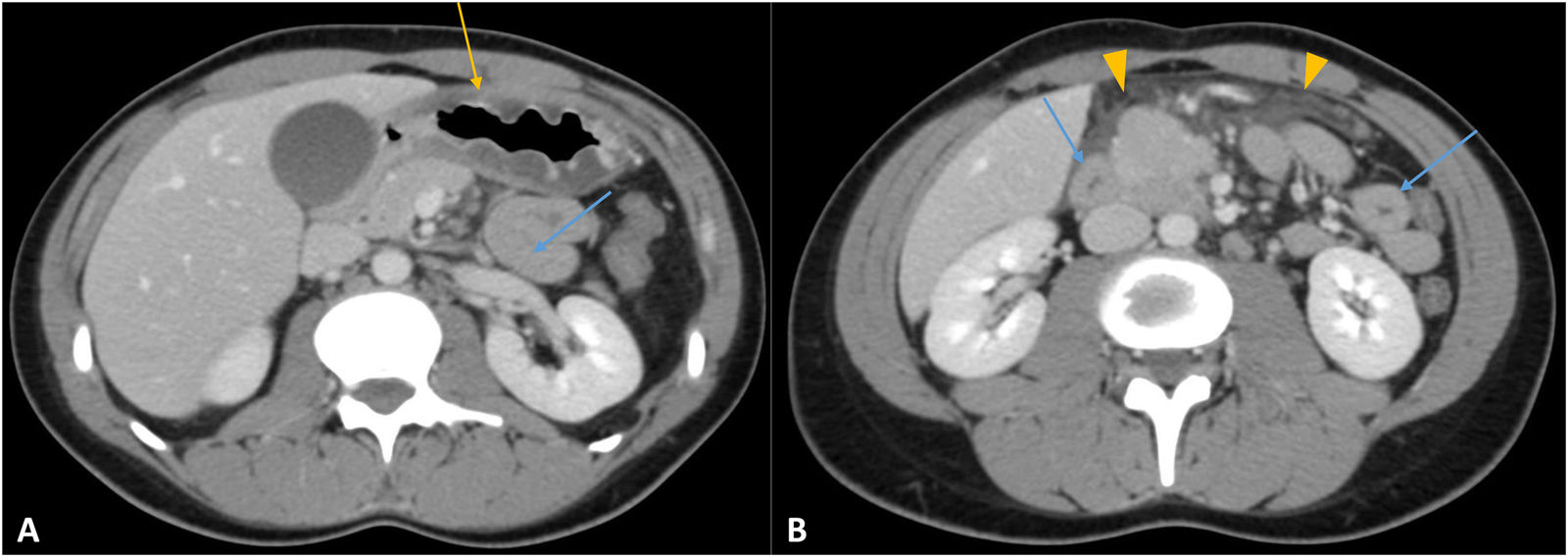

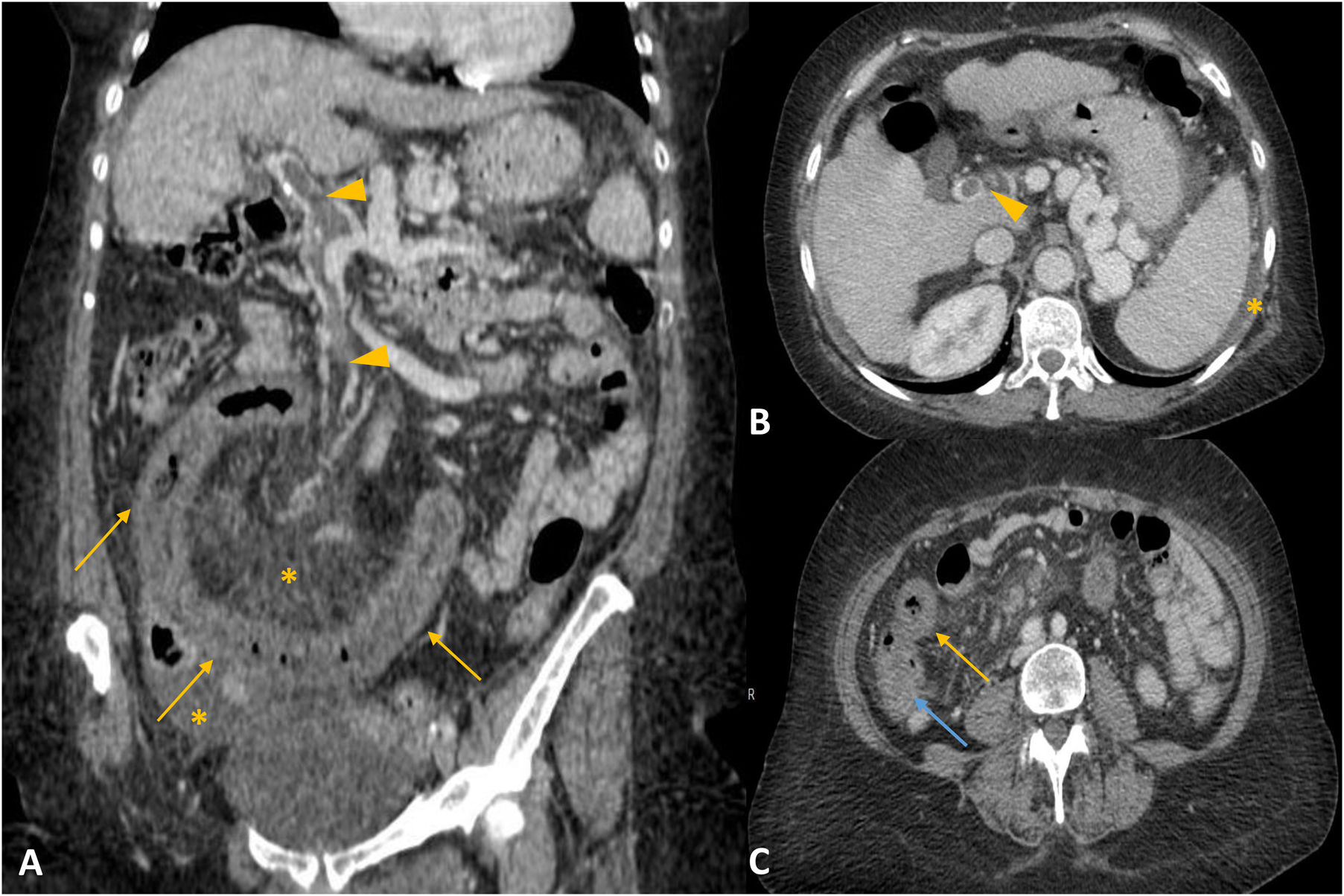

Anisakiasis is a zoonotic infection caused by Anisakis larvae, which can invade the gastrointestinal tract of humans through accidental ingestion. The pathophysiological mechanism is the result of an immediate, IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction when the body recognises Anisakis simplex antigens as foreign. Anisakis infections have become more common in recent years, associated with increased consumption of raw, undercooked or marinated fish.11 The prevalence of Anisakiasis has been studied in Madrid, where it is estimated that 12.4% of the population have specific IgE for Anisakis simplex.12 Anisakiasis is mainly divided into gastric and intestinal subtypes. Symptoms appear one to eight hours after eating raw fish and typically include epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting. Many patients also experience itching of the oropharynx and allergic reactions ranging from hives to anaphylactic shock. These symptoms can mimic a shellfish allergy. The main findings on MDCT with IVC include (Fig. 2) symmetric, segmental wall thickening (5−12 cm), accompanied by a decrease in wall enhancement. Anisakiasis has a tendency to be located in the ileum. Complications include signs of small bowel obstruction, ascites, oedema and mesenteric congestion, and even invasion of the omentum.11,13 Intestinal ischaemia should be considered within the differential diagnosis due to its similar imaging findings (segmental wall thickening with an oedematous appearance), although proximal intestinal obstruction is more specific for Anisakis infection.1,3,11,13 In cases of intestinal obstruction, anisakiasis also has to be distinguished from neoplasms, Crohn's disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, other parasitic and bacterial infections, and intussusception. In terms of treatment, removal of the parasite (endoscopy or surgery) is curative. Antiparasitic drugs such as albendazole are also used.11,13

Anisakiasis. A and B) Axial slices of computed tomography with intravenous contrast. A 25-year-old female patient with abdominal pain and vomiting after eating sushi. Gastroscopy was normal and laboratory tests show eosinophilia. Concentric thickening of the gastric wall (yellow arrow in A) and of a segment of the small bowel (blue arrows in A and B) with loss of wall enhancement. Free fluid between loops (arrow heads in B). Both the duodenum and the proximal jejunum were affected.

Graft versus host disease (GVHD) is a multisystem complication which occurs after transplantation of haematopoietic stem cells. The risk of developing GVHD depends on the type of graft, the degree of matching of the human leucocyte antigen, and the characteristics of the donor and recipient. Acute GVHD generally occurs within the first 100 days after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and the small bowel is affected in 75–100% of cases.14 The exact incidence of acute GVHD after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is unknown. Clinical presentation consists of maculopapular erythema, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea. MDCT with IVC findings include moderate wall thickening, with diffuse and symmetric involvement and a stratified enhancement pattern (target sign with water-density) (Fig. 3). It can affect the small bowel, large bowel, or both. Mesenteric engorgement and oedema, mild loop dilation, and ascites may also be seen. The main differential diagnosis is Crohn's disease, where the clinical context is essential. In addition, GVHD has diffuse intestinal involvement (typically extending from the duodenum to the rectum) and a mild degree of wall thickening.3,4,14 Infectious causes are more difficult to rule out in the differential diagnosis, especially when patients are immunosuppressed. Stool cultures are important to rule out Clostridium difficile. Rectal biopsy differentiates GVHD from viral pathogens, such as cytomegalovirus.15 Treatment consists of immunosuppressive therapies depending on the severity of the disease and prophylaxis to prevent infections.

Graft versus host disease. A-C) Axial slices of computed tomography with intravenous contrast. A 68-year-old male with bone marrow transplant one month previously who presented with fever and diarrhoea. Diffuse, symmetrical wall thickening, oedema of the submucosa (yellow arrows in B and C) and hyperenhancement of the mucosa (blue arrows in B and C) of the entire small bowel. The same findings are seen in the large bowel. Large amount of free fluid (arrow heads in A-C).

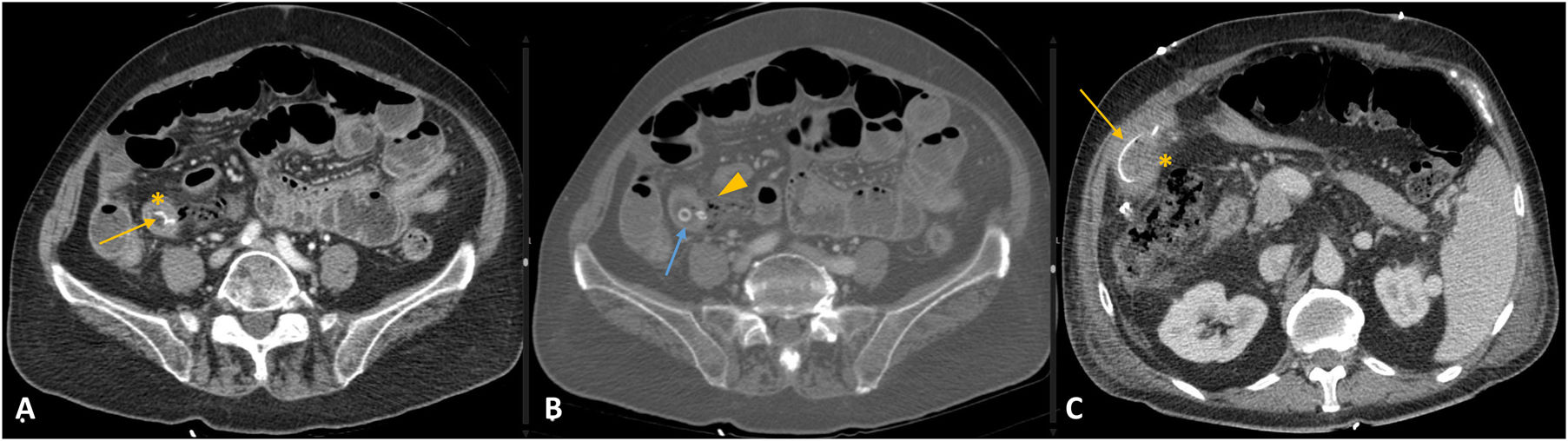

Diverticula are sac-like pouches of the mucosa and submucosa which protrude through the muscle layer of the bowel wall. In decreasing order of frequency, diverticula are located in the colon, duodenum, oesophagus, stomach, jejunum and ileum. In the general population, small bowel diverticula are found in 2–4% of imaging tests, and up to 60% of patients with diverticula in the small bowel also have diverticula in the colon.16,17 Small bowel diverticula are often asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally on imaging tests. Diverticulitis occurs when the neck of a diverticulum becomes occluded, and this can lead to microperforation and inflammation of the adjacent mesenteric fat. Diverticula can be classified into duodenal (the most common) and jejunoileal.16,17 The most common manifestation in duodenal diverticula is complicated diverticulitis with perforation or bleeding (Fig. 4), while in jejunoileal diverticula, uncomplicated diverticulitis is more typical. MDCT findings are similar to those in acute large bowel diverticulitis (Fig. 4).1,12 Asymmetric, focal or segmental thickening is seen, with homogeneous enhancement of the small bowel wall adjacent to a diverticulum with mesenteric fat stranding in the vicinity, engorgement of the mesenteric vessels and free fluid. Small bowel diverticulitis can also be complicated by a perforation and lead to extraluminal air and even abscess formation.16,17 Cancer is the most important differential diagnosis in cases with significant asymmetric wall thickening and lymphadenopathy,3,16,17 but not forgetting that both conditions can coexist. In cancer, the asymmetry of the wall thickening is more pronounced, and may also be accompanied by retraction of the mesentery. The differential diagnosis should also include foreign bodies, intestinal scleroderma and Meckel's diverticulitis. Treatment is usually conservative for patients who are clinically stable, with surgery reserved for complicated cases.16,17 Ultrasound-guided treatment can be performed for complications such as abscesses.

Diverticulitis. A) B-mode ultrasound. B-D) Axial slices of computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast. Case 1: ultrasound shows segmental thickening of the small bowel (arrowhead in A). CT shows uncomplicated Meckel's diverticulitis (arrow in B) with peri-diverticular fat stranding (asterisk in B). Case 2: perforation of duodenal diverticulitis (duodenal diverticulum in C; pneumoperitoneum in D).

Meckel's diverticulum is a true diverticulum (contains all the layers of the bowel wall) and is the most common congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract.18,19 It represents a persistent remnant of the omphalomesenteric duct and occurs in 2% of the population. It is located on the antimesenteric border of the ileum at 45−90 cm from the ileocaecal valve.19 Most Meckel's diverticula are asymptomatic, but in some cases the following complications can be observed: bleeding, intussusception, intestinal obstruction and diverticulitis (Fig. 4). The findings on MDCT are similar to the diverticulitis described above. The differential diagnosis should include appendicitis, Crohn's disease and diverticulitis of the caecum.18,19

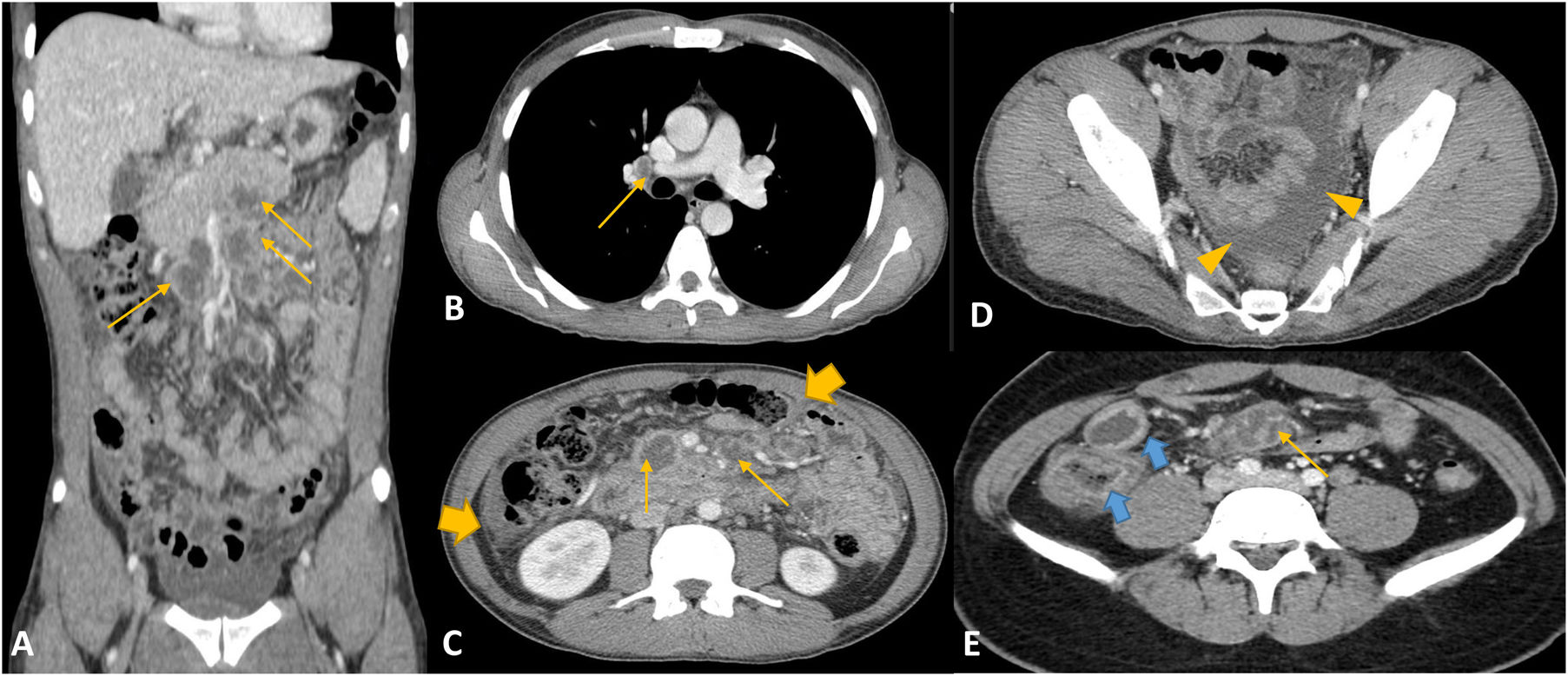

Recurrence of tuberculosisMycobacterium tuberculosis can reach the intestinal mucosa through the ingestion of infected sputum in the case of concomitant active pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) (20-25% of cases), by ingestion of milk contaminated by Mycobacterium bovis (very rare in developed countries), or by haematogenous spread from an active pulmonary focus or a disseminated infection.20,21 A third of the world's population is infected with TB. Extrapulmonary forms of TB affect 20% of immunocompetent patients, compared to 50% of immunosuppressed patients, with intestinal TB, found in 11% of patients, being the sixth most common. There is a currently a resurgence of TB, due to the increase in immunosuppressed patients (particularly HIV), multidrug-resistant strains and the increasing use of immunosuppressive drugs.20,21 The most common locations for abdominal involvement are, in descending order, the lymph nodes, the genitourinary tract, the peritoneum and the gastrointestinal tract.20,21 The most common symptoms are fever, weight loss and abdominal pain. Intestinal TB is particularly common in the ileocaecal region, affected in 90% of cases, due to the high density of lymphoid tissue. Inflammatory involvement generally causes circumferential and segmental wall thickening of the terminal ileum and caecum, with stratified enhancement (target sign with water density), and in some cases (less common presentation) it can lead to a mass-type and therefore asymmetric lesion.3,6,20,21 The lymphadenopathy has a characteristic appearance with hypodense centres and hyperuptake around the periphery (caseous necrosis)3,6,20,21 (Fig. 5). TB can also cause peritonitis (Fig. 5) and be difficult to distinguish from peritoneal carcinomatosis, although that is likely to show more pronounced implants in the omentum. It is often difficult to distinguish intestinal TB from Crohn's disease, as enteritis caused by M. tuberculosis can cause stricturing and fistulas, but lymphadenopathy with caseous necrosis is not common in Crohn's disease.6.20,21 Because of the ileocaecal region involvement, amoebiasis or a primary tumour of the caecum should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. The usual treatment is therapy with anti-tuberculosis drugs lasting 6–9 months, with surgery reserved for the most complex cases.

Tuberculosis. A-E) Coronal (A) and axial (B-E) slices of computed tomography with intravenous contrast. Case 1: 27-year-old male with general syndrome and abdominal pain. Necrotic lymphadenopathy conglomerates in mediastinal and peritoneal regions (arrows in A-C and E). There is also peritoneal enhancement (thick arrow in C) with loculated free fluid (arrow heads in D). Case 2: HIV-positive male with right iliac fossa pain. Asymmetrical segmental wall thickening in the ileocaecal region with oedema of the submucosa and hyperaemia of the mucosa (blue arrows in E) and intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy (thin arrows in E).

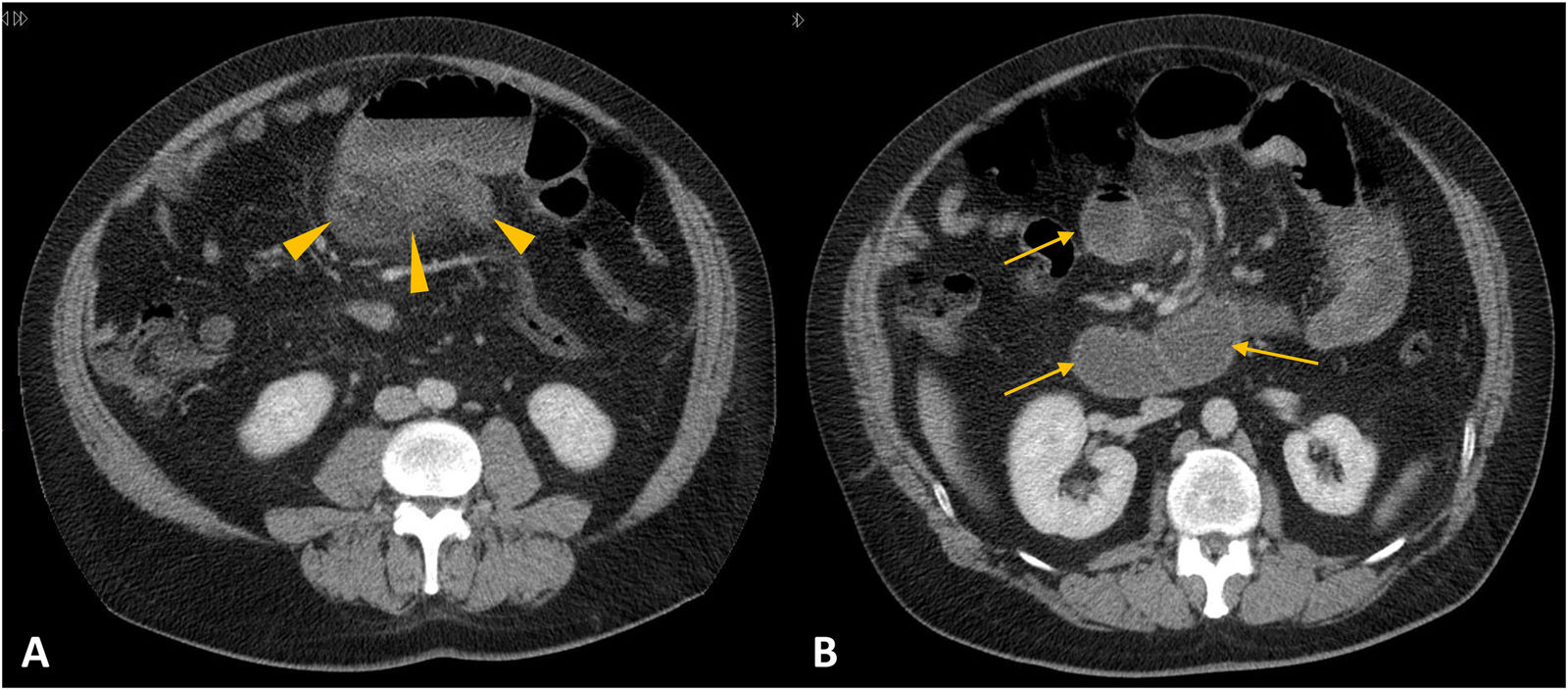

Intestinal ischaemia refers to vascular compromise of the bowel and its mesentery which, in the acute setting, has a very high mortality rate if not treated urgently. The most common cause is arterial, such as embolism (40–50%) and mesenteric arterial thrombosis (25–30%), followed by mesenteric venous thrombosis (5–10%). It can also be secondary to bowel obstruction (closed loop, adhesions, tumours) or over-distension of the loops leading to hypoperfusion (hypovolaemia, heart failure, toxins, etc).22–24 Clinical diagnosis is difficult because the symptoms are nonspecific (severe abdominal pain accompanied by nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, blood in the stool). The radiological findings vary greatly, depending on the degree of involvement. In ischaemic bowel of arterial origin, MDCT with IVC shows the wall to be thinned (paper-thin) with either no or decreased wall enhancement. Symmetric, segmental thickening of the bowel wall is the most common MDCT sign in intestinal ischaemia of venous origin.22 The target sign (with water density) can be an early finding relating to oedema of the submucosa and hyperaemia of the mucosa and/or the muscularis propria.22,23 We may also find a thrombus or a reduction in the lumen of the superior mesenteric artery or superior mesenteric vein. In mesenteric venous thrombosis, mesenteric fat stranding and ascites are common (Fig. 6).6,22–24 The presence of solid visceral infarcts points to a cardioembolic cause, particularly in patients with atrial fibrillation. As an atypical presentation of mesenteric ischaemia, there may be high attenuation of the bowel wall in the presence of intramural bleeding or haemorrhagic infarction (white enhancement pattern). Pneumatosis intestinalis, portal/mesenteric vein gas and pneumoperitoneum occur in the most severe cases when there is a transmural infarction and/or perforated bowel. However, there are many non-ischaemic causes which can lead to pneumatosis intestinalis (infections, inflammation, neoplasms, barium or endoscopic studies).22–24 The differential diagnosis includes intestinal angioedema, which causes massive wall oedema and ascites; small bowel vasculitis, characterised by segmental wall thickening, with oedema of the submucosa and target sign and ascites; shock bowel, which causes intense enhancement of the mucosa and oedema of the mucosa and mesentery; and Crohn's disease.23,24 Treatment depends on the severity of the findings, but is usually surgical and/or endovascular, with systemic anticoagulation for cases of venous thrombosis.

Venous mesenteric ischaemia. A-C) Coronal (A) and axial (B-C) slices of computed tomography with intravenous contrast. Thrombosis of the main portal and superior mesenteric vein (arrowheads in A and B). Marked, symmetrical segmental wall thickening (yellow arrows in A and C), hyperenhancement of the mucosa (blue arrow in C), mesenteric fat stranding and vascular engorgement (asterisk in A). Pelvic and peri-splenic free fluid (asterisks in A and B).

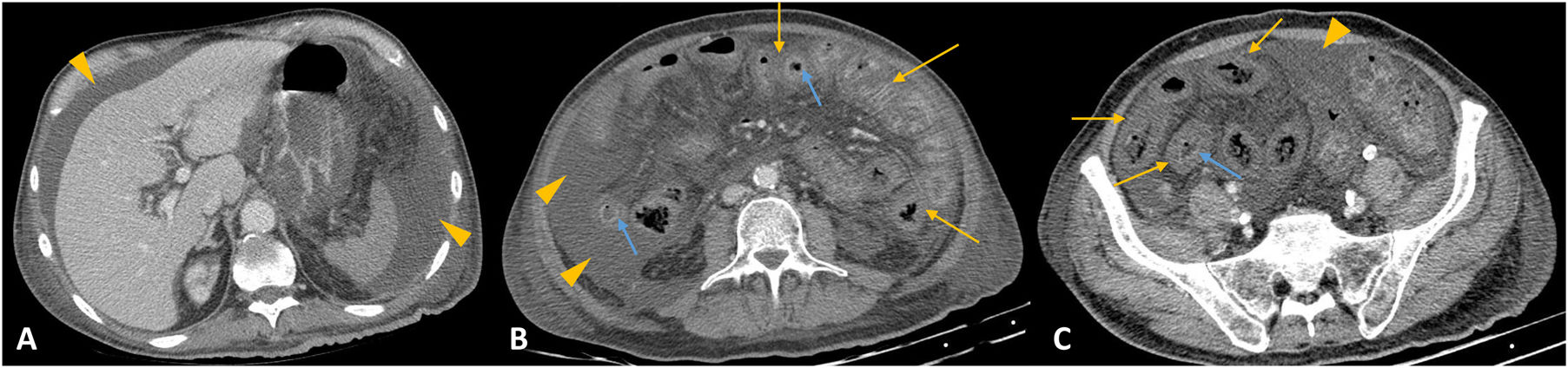

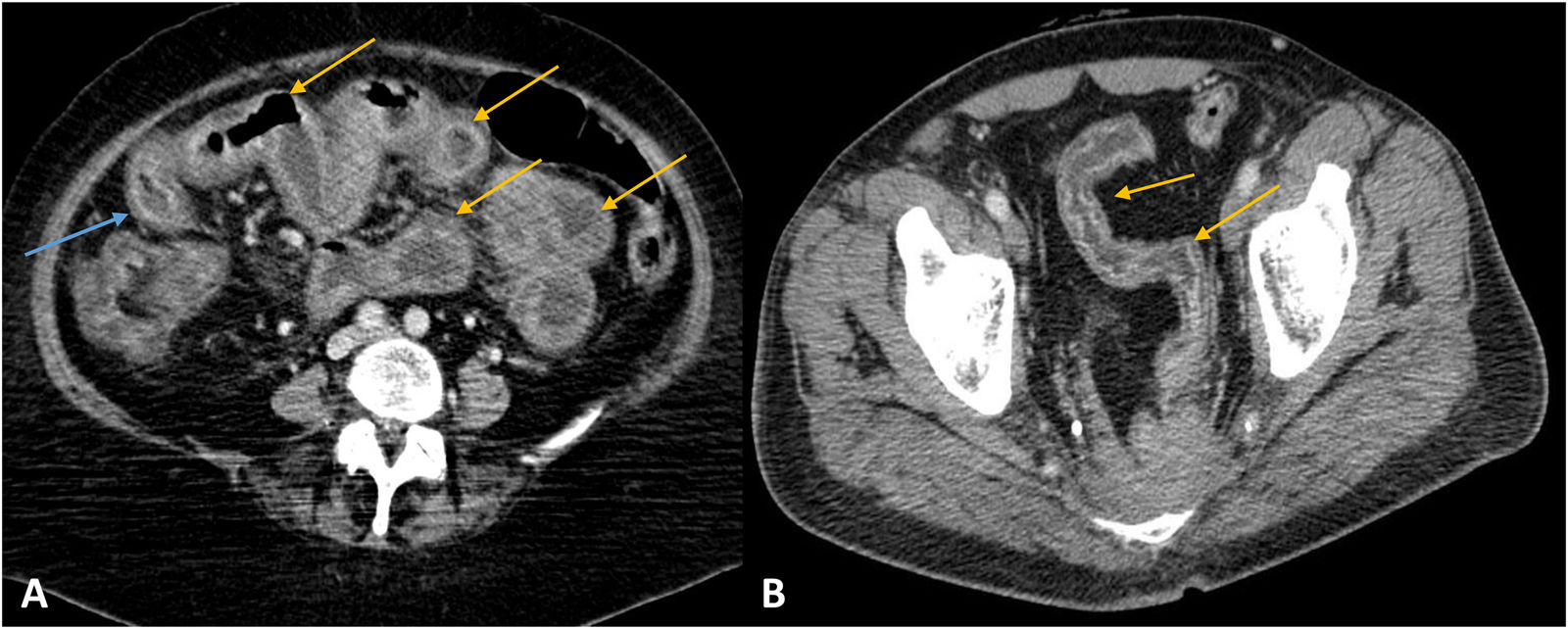

This is one of the most common types of toxicity related to classic cytotoxic agents, and is due to nonspecific damage to the rapidly dividing cells in the gastrointestinal mucosa.25,26 Patients with chemotherapy-induced enteritis develop bloating and abdominal pain, and very often diarrhoea, within a few weeks of starting treatment. A number of chemotherapy agents used in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and floxuridine) can cause enteritis, which can be either diffuse or predominantly affect the distal ileum (Fig. 7).25,26 Radiological findings include diffuse, symmetric thickening of the bowel wall and loop dilation. The typical appearance of enteritis on MDCT with IVC is the target sign with water density (oedema of the submucosa with hyperaemia of the mucosa and serosa) (Fig. 7). Bowel wall thickening may also show normal uptake.25,26 In the differential diagnosis, the clinical context is essential, and must include ischaemia and radiation-induced enteritis.1,3 Management of these patients usually includes a switch in chemotherapy.

Toxicity. A and B) Axial slices of computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast. Case 1: chemotherapy-induced enteritis. Diffuse, symmetrical wall thickening in small bowel loops (yellow arrows in A), with oedema of the submucosa and hyperenhancement of the mucosa, compatible with diffuse enteritis. Chemotherapy was discontinued and the follow-up CT scan was normal. Case 2: radiotherapy-induced enteritis. Pelvic ileum segment with homogeneous wall thickening and loss of wall enhancement due to the development of transmural fibrosis (arrows in B).

This is the damage to the mucosa and the intestinal wall caused by radiotherapy to the abdominal and pelvic regions; 5–15% of patients develop moderate-to-severe radiation-induced enteritis.25,26 When acute, symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, while chronic enteritis can cause bloody diarrhoea, steatorrhoea and weight loss, and tends to occur from 6 to 24 months after treatment. The distribution depends on the radiotherapy fields and most often includes the rectum, sigmoid colon and small bowel loops located in the pelvis.25 In acute radiotherapy-induced enteritis, the findings do not differ much from those in chemotherapy. In chronic enteritis, symmetrical segmental wall thickening can be seen, with loss of enhancement (target sign with fat density). The decreased wall enhancement is due to the development of transmural fibrosis (Fig. 7). There may also be an increase in pelvic fat and thickening of the perienteric fibrous tissue.3,6,25 In the differential diagnosis, the clinical context is fundamental, and includes Crohn's disease, intestinal ischaemia, lymphoma and primary tumours of the small bowel. Treatment consists of reduction or cessation of radiotherapy, a low-residue diet, and surgery for strictures and fistulas.

Other causesEctopic pancreatic tissueEctopic pancreatic tissue is defined as any pancreatic tissue without anatomical or vascular continuity with the orthotopic pancreas.27,28 The prevalence in the general population is approximately 0.25%. More than 90% of cases of pancreatic ectopic tissue are found in the upper gastrointestinal tract (stomach, duodenum and proximal jejunum).27,28 The presence of ectopic pancreatic tissue is usually asymptomatic. Symptomatic patients may present with abdominal pain, dysphagia and, in some rare and complicated cases, pancreatitis (Fig. 8), pseudocysts, upper gastrointestinal bleeding and adenocarcinoma. Ectopic pancreatic tissue may give the appearance of asymmetric focal wall thickening with enhancement, and is normally found in the submucosa. It appears on imaging as tissue with homogeneous enhancement (similar to the normal pancreas) or with a cystic area (acinar component or pseudocyst), with a tendency to endoluminal growth.27,28 The definitive diagnosis is obtained by biopsy or surgical resection. Ectopic pancreatic tissue located in the stomach (most common location, the antrum in particular) can be difficult to differentiate from other hypervascular submucosal lesions (glomus, carcinoid tumours) or gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST). GIST show ulceration, exophytic growth tendency and variable enhancement.27,28 Treatment usually consists of laparoscopic resection in symptomatic cases.

Ectopic pancreatic tissue. A and B) Axial slices of computed tomography with intravenous contrast. Dilation of duodenum and proximal jejunum (arrows in B). Tissue with poorly defined borders adjacent to a jejunum segment with significant fat stranding and engorgement of nearby mesenteric vessels (arrowheads in A). The pathology diagnosis was ectopic pancreatic tissue with signs of acute and chronic pancreatitis.

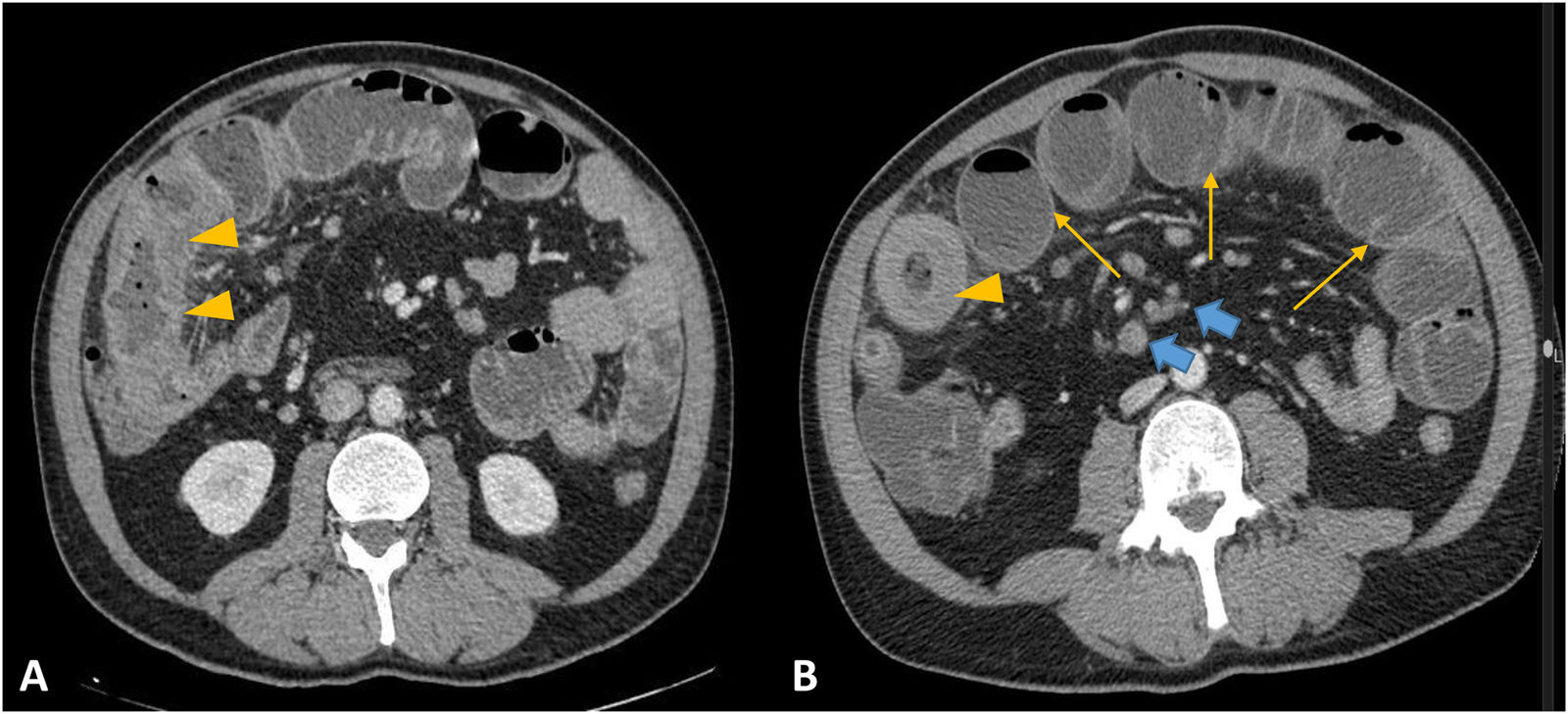

Detection of foreign bodies is relatively common in MDCT of the abdomen and pelvis. The presence of foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract can be the result of medical disorders (bezoars), previous medical procedures (displaced feeding tubes, biliary stents, etc), ingestion of diagnostic devices (endoscopic capsules), or accidental or non-accidental ingestion of other objects (fish bones, chicken bones, batteries, etc). Most foreign bodies that reach the gastrointestinal tract (less than 2.5 cm in diameter) pass easily into the stool, but hard or sharp objects such as fish or chicken bones and toothpicks can cause perforation of the bowel (Fig. 9).29 MDCT allows the foreign body to be located (intraluminal or extraluminal) and is also useful for determining its nature. Multiplanar reconstructions (MPR) are very useful in diagnosis. Fish and chicken bones are seen on MDCT as linear, hyperdense structures (Fig. 9).29 The affected bowel segment usually shows focal and asymmetric wall thickening, accompanied by perienteric fat stranding.29 The most common sites for perforated bowel are segments with pronounced angles or the more mobile regions (ileum, ileocaecal region and rectosigmoid junction). In cases with complications such as perforation, the indicated treatment is surgery.

Foreign bodies. A-C) Axial slices of computed tomography with intravenous contrast. Case 1: a linear and hyperdense structure can be seen in the ileum lumen, compatible with a chicken bone (yellow arrow in A). In addition, there is a round hyperdense image with a hypodense centre, compatible with an olive stone (blue arrow in B). Signs of intestinal perforation (arrowhead in B). The affected segment of the ileum shows focal and symmetrical wall thickening (asterisk in A). Case 2: biliary stent which has migrated distally (arrow in C). The affected segment of jejunum show segmental wall thickening with homogeneous enhancement and stranding of the adjacent fat (asterisk in C).

Crohn's disease is a chronic granulomatous inflammatory disease which can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract with multiple-site and discontinuous involvement. It has a prevalence in Europe of 322 per 100,000 people.4 In 80% of cases, the small bowel is affected, particularly the terminal ileum. There is a peak of incidence between the ages of 15 and 25. The most common symptoms are diarrhoea, pain, weight loss, fever, malabsorption and perianal fistulas. MDCT findings are segmental, symmetrical, wall thickening (1–2 cm), with homogeneous or stratified enhancement. The target or double-halo sign is common in active lesions, accompanied by perienteric hypervascularisation of the vasa recta (comb sign). The fibrofatty proliferation has slightly increased enhancement. There may be enlarged lymph nodes (3–8 mm) and extramural complications such as phlegmons or abscesses, fistulas, strictures or pre-stricture dilation.1,3–6

Small bowel adenocarcinomaThis causes malignant tumours of the glandular epithelium. Despite the low incidence (less than 1% of all primary gastrointestinal neoplasms), they are the most common primary cancers of the small bowel and occur mainly in the duodenum or jejunum.30,31 Patients may present with abdominal pain, bowel obstruction and anaemia. On MDCT, adenocarcinomas appear as solitary, focal or segmental, asymmetric, invasive lesions with destruction of the mucosa, which cause narrowing of the lumen, with a tendency to ulceration. After contrast administration, moderate, heterogeneous enhancement can be seen. Gradual narrowing of the lumen can lead to partial or complete obstructions. They tend to invade the entire thickness of the wall, spreading into the adjacent mesenteric fat, leading to a desmoplastic reaction. They metastasise to regional lymph nodes, liver or peritoneum.31 The differential diagnosis should include both malignant and benign primary tumours of the small bowel and lymphoma.

LymphomaLymphomas can appear as primary tumours of the small bowel or they can develop as secondary intestinal involvement in the context of lymphoproliferative disease. They represent 15–20% of small bowel tumours.32 B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is the most common subtype affecting the small bowel,3,6,32,33 while T-cell lymphomas are less common and are associated with coeliac disease.32,33 Primary involvement of the gastrointestinal tract is the most common form of extranodal lymphoma (30–40% of cases), the terminal ileum being the region most often affected.32 A single bowel segment may be involved or multiple regions, especially in T-cell lymphoma. Lymphoma is one of the few cancerous causes that can present with segmental or diffuse thickening of the bowel wall (neoplasms usually cause focal thickening).6,32,33 Patients present with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, weight loss and fever. Gastrointestinal lymphoma is a great mimicker. It has a large variety of radiological manifestations, but with three main patterns. It can infiltrate diffusely, causing homogeneous thickening of the entire wall of the small bowel (Fig. 10). It can manifest with the formation of polyps, or it can be exophytic, with the development of authentic masses which may cause ulceration and bowel fistulas. A typical characteristic of lymphoma when exophytic is aneurysmal dilation of the lumen of the affected intestinal loops, due to the loss of muscle tone in the invaded wall.32,33 Lymphoma with polyp formation can cause intussusception. Mesenteric involvement with lymphadenopathy (Fig. 10), preservation of mesenteric fat and associated splenomegaly support the diagnosis.3,6,32,33 Differential diagnosis should include adenocarcinoma of the small bowel and Crohn's disease.1,3,32 The lymph nodes in lymphoma tend to be more voluminous than those in adenocarcinoma. Surgical treatment is usually considered when the primary disease is limited to a single organ.

Lymphoma. A and B) Axial slices of computed tomography with intravenous contrast. Significant segmental wall thickening of the distal ileum with homogeneous enhancement (arrowheads in A and B) causing bowel obstruction (arrows in B). Lymphadenopathy can be seen in the adjacent mesenteric fat (blue arrows).

After adenocarcinoma and lymphoma, the next most common small bowel tumours are carcinoid and GIST, although they have a significantly lower prevalence.

ConclusionMDCT is one of the main diagnostic methods in small bowel disease. Differential diagnosis is broad and challenging, as on top of the most common disorders, we have to consider many other causes, such as those we have discussed here. In addition to recognising the specific features of each different disorder, we must always correlate them with the symptoms, laboratory tests and personal history, as radiological manifestations very often overlap.

- 1

Responsible for the integrity of the study: EMD and JC.

- 2

Study conception: EMD and JC.

- 3

Study design: EMD and JC.

- 4

Data acquisition: EMD and JC.

- 5

Analysis and interpretation of the data: EMD and JC.

- 6

Statistical processing: not applicable.

- 7

Literature search: EMD and JC.

- 8

Drafting of the article: EMD and JC.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with relevant intellectual contributions: EMD and JC.

- 10

Approval of the final version: EMD and JC.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Marín-Díez E, Crespo del Pozo J. Aproximación diagnóstica al engrosamiento parietal del intestino delgado: más allá de la enfermedad de Crohn y el cancer. Radiología. 2021;63:519–530.