Supplement “Pulmonary Interstitial Pathology”

More infoThe term idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis refers to a rare interstitial lung disease that predominantly involves the upper lobes. It has been considered a rare subtype of interstitial lung disease since 2013, when it was included in the joint consensus statement on the diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases published by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS).

Currently, two distinct types of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis are recognized: the idiopathic type for cases in which it has not been possible to establish a specific etiology and a secondary type associated with a variety of different causes.

The diagnosis of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis must be managed from a combined clinical and radiological perspective. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) is the imaging method of choice for the evaluation and diagnosis of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis. In many cases, the diagnosis will be based exclusively on the HRCT findings and histologic confirmation will be unnecessary.

This article describes the clinical, radiological, and histological characteristics of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis, discussing the different associations with this entity and its differential diagnosis.

La fibroelastosis pleuroparenquimatosa (FEPP) idiopática es una rara enfermedad pulmonar intersticial predominante en los lóbulos superiores. Desde 2013 se considera un subtipo raro de enfermedad pulmonar intersticial, incluyéndose en el estudio de consenso para el diagnóstico de las enfermedades pulmonares intersticiales establecido por la American Thoracic Society y la European Respiratory Society.

Actualmente se reconocen 2 formas distintas de FEPP. Una forma idiopática, en la que no se logra identificar una etiología específica, y una forma secundaria, asociada a múltiples y diferentes causas.

El diagnóstico de la FEPP debe manejarse desde una perspectiva clínico-radiológica. La tomografía computarizada de alta resolución (TCAR) es el método de imagen de elección en la evaluación y el diagnóstico de la FEPP. En muchos casos, el diagnóstico se basará exclusivamente en los hallazgos de la TCAR, no siendo necesaria una confirmación histológica.

En este artículo se describen las características clínicas y radiopatológicas de la FEPP, discutiéndose las diferentes asociaciones con esta entidad y su diagnóstico diferencial.

The term idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (IPPFE) was coined in 2004 to describe the existence of pleural and subpleural fibroelastosis predominantly affecting the upper lobes.1 A similar entity known as idiopathic pulmonary upper lobe fibrosis had previously been described in the Japanese literature.2

In 2013, IPPFE was considered a rare subtype of interstitial lung disease in the latest update to the international classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Since then, and as a result of a better understanding of the diagnostic criteria, its incidence and prevalence have increased significantly. In the same centre, over 10 years, IPPFE represented 7.7% of the consecutive cases diagnosed with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias.3

IPPFE has well-defined radiological and pathological manifestations.1,4–7 It affects the upper lobes by combining a fibrosing process of the visceral pleura and fibroelastotic changes in the underlying lung parenchyma.

The clinical, radiological and pathological findings have a certain similarity to those described in the apical pleural “cap”, a term applied to a pattern of focal pulmonary fibrosis characterised by irregular pleural thickening of less than 5mm located at the lung apices8–13 (Fig. 1). Histologically, it is characterised by a fibroelastic scar lesion of the visceral pleura and adjacent pulmonary parenchyma12,14 (Fig. 1).

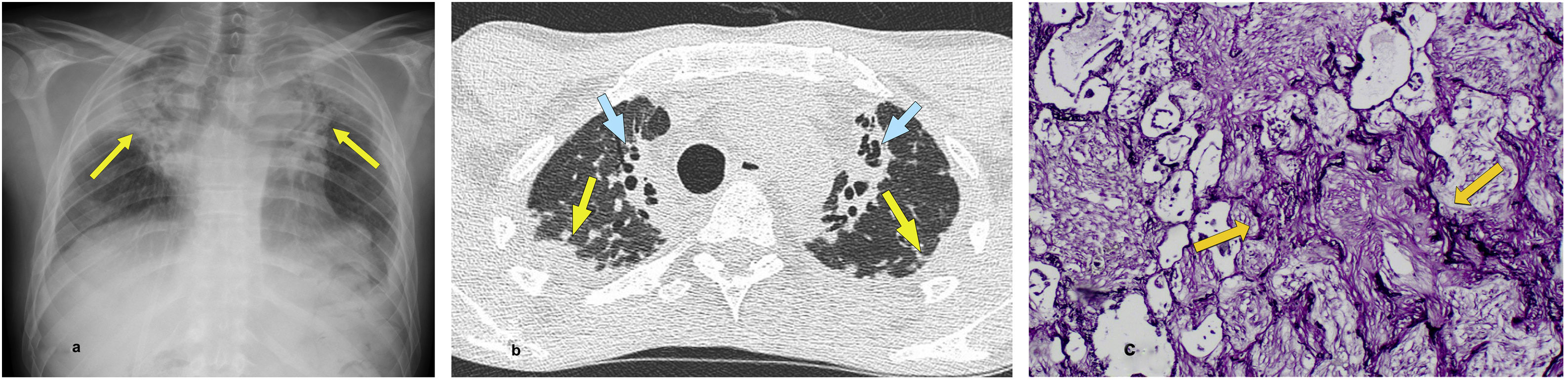

PPFE in a 30-year-old man with Hodgkin’s disease and allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) who developed pulmonary graft versus host disease. (a) A simple posterior-anterior chest radiograph reveals extensive biapical pulmonary consolidation with loss of upper lobe volume (arrows). (b) The HRCT image reveals extensive consolidation with a retractile component and bilateral pleural and subpleural involvement (arrows). At the paramediastinal level, a retractile consolidation with traction bronchiectasis was observed. (c) A section of a lung biopsy showing subpleural fibroelastosis. The typical pattern of PPFE is characterised by the presence of intraalveolar fibrosis and interstitial elastosis (arrows).

Courtesy of Dr Laura López Vilaro.

Although the apical pleural “cap” was originally thought to be the result of tuberculous infection,15 the associated presence of granulomatous inflammation has not been successfully demonstrated.12,14

Most cases of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE) are considered idiopathic. However, better knowledge of this entity has facilitated the description of various ‘non-idiopathic’ associations of PPFE, including connective tissue diseases, interstitial fibrosing diseases, occupational exposures (aluminium silicate dust), immunosuppressive therapy, chemotherapy and chronic/recurrent infections.16–22 PPFE has also been described as a late complication of lung transplantation and haematopoietic stem cell transplantation23,24 (Table 1).

Types of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE).

| Idiopathic PPFE |

| Non-idiopathic PPFE |

| 1. Restrictive allograft syndrome as a complication of lung transplantation and haematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| 2. Fibrosing interstitial lung disease (usual interstitial pneumonia, hypersensitivity pneumonitis) |

| 3. Chronic or recurrent bronchopulmonary infection (aspergillosis, non-tuberculous mycobacteria) |

| 4. Autoimmune or connective tissue diseases (scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease) |

| 5. Family history of pulmonary fibrosis |

| 6. Genetic mutation-associated pulmonary fibrosis (telomere shortening) |

| 7. Chemotherapy treatment (cyclophosphamide and carmustine) and radiation therapy |

| 8. Occupational respiratory diseases (asbestos and aluminium) |

Taken from Chua et al.5

Exceptionally, cases of PPFE with a familial/genetic basis,25 unilateral forms as a late complication of open thoracic surgery or video-assisted thoracic surgery,26–28 cases in children treated with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or bone marrow transplantation29 and cases associated with autoimmune diseases such as MPO-ANCA-positive (myeloperoxidase anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody) microscopic polyangiitis30 have been reported.

Clinically, PPFE is similar to other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. The average age of presentation is in a person’s forties. There is no predilection for gender, and it affects men and women equally.7

As a result of marked retraction of the upper lobes and reduced chest wall volume, progressive flattening of the rib cage and deep suprasternal notch have been described clinically and radiologically5 (Fig. 2).

Deep suprasternal notch associated with PPFE. (a) The HRCT image of the lung apices reveals slight pleural nodular thickening (yellow arrows). The presence of a pronounced suprasternal notch (blue arrow) stands out. (b) Subpleural retractile consolidations (yellow arrows) are observed in a slightly more cranial plane.

The progression of the disease is variable, ranging from an indolent course to rapid progression. Although symptoms are non-specific, progressive exertional dyspnoea is the most common symptom. Other symptoms include a dry cough and chest pain. Spontaneous or recurrent episodes of pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum are common in 30%–75% of cases.19 Compared with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), the frequency of spontaneous pneumothorax is significantly higher in patients with PPFE. In the advanced stages of the disease, lung function shows a restrictive pattern.

Anatomical pathology characteristicsIt has been suggested that PPFE represents a pattern of pulmonary response to various clinical situations. Histologically, it is characterised by intense fibroelastosis in the visceral pleura of the upper lobes.7 In addition, and without being a predominant feature, peribronchiolar and alveolar wall infiltration can also be observed, which is deposited into the pleura.6 (6) Occasionally, fibroblastic foci are at the edge of the fibrotic zones adjacent to the normal pulmonary parenchyma.19

Histologically, Pradere et al.31 described a form of peribronchiolar fibroelastosis associated with chronic asthma, or idiopathic, in the upper lobes of women who were non-smokers; high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) revealed thickening and deformity of the bronchial walls, presence of bronchiectasis, and subpleural retraction of the pulmonary parenchyma. Airway-centred fibroelastosis has also been described in two women (aged 19 and 60, respectively) as a late complication (after six and nine years) of chemotherapy treatment.32

Radiological manifestationsAlthough at the time of diagnosis, the findings are usually located in the lung apices, the progression of the disease can manifest as a diffuse multilobar process.6

Initially, the chest X-ray may be normal. In more advanced stages of the disease, irregular and bilateral pleural thickening will be observed at the lung apices, bilateral hilar retraction associated with distortion of the bronchovascular structures, and significant loss of pulmonary volume in the upper fields.

HRCT is the best imaging method for assessing patients with PPFE. In the early stages of the disease, as it is more sensitive than conventional radiological studies, it may reveal the manifestations and distribution of pleuroparenchymal lung lesions. Multiplanar reconstructions will be very useful in assessing the distribution and extent of the disease.

In HRCT, the most common findings include the presence of dense subpleural consolidations with traction bronchiectasis and structural distortion of the upper lobes33,34 (Fig. 3). The pleura is usually thickened in areas where subpleural fibrotic changes are observed.

PPFE in a 80-year-old man with no relevant medical history. (a) The HRCT image in a coronal reconstruction plane highlights the biapical pulmonary distribution of pleural and subpleural thickening (arrows). (b) The transverse slice at the level of the lung apices reveals in greater detail the pleural and subpleural retractile consolidation involvement (arrows).

A characteristic feature of PPFE is the clear delimitation between the fibrotic areas and the adjacent normal parenchyma. Co-existing interstitial patterns of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) or non-specific interstitial pneumonia are sometimes observed.

The diagnosis of PPFE should be made with a multidisciplinary approach. Based on the radiological criteria described, Reddy et al.6 have established three morphologically distinct groups in the differential diagnosis of PPFE: 1) definitive PPFE: presence of pleural thickening with subpleural fibrosis in the upper lobes and minimal or no involvement of the lower lobes; 2) compatible with PPFE: presence of pleural thickening in the upper lobes and pulmonary fibrosis not localised in the upper lobes or with disease characteristics in other locations, and 3) inconsistent with PPFE: absence of criteria previously described.1,6,7,35

In HRCT, it may be difficult to differentiate between apical pleural “cap” and PPFE lesions. However, the presence of bilateral apical subpleural nodular thickening associated with a subpleural reticular pattern with traction bronchiectasis, loss of upper lobe volume, and bilateral apical hilar retraction are findings suggestive of PPFE.36,37

The differential diagnosis will be established between the processes that present with apical pleural and parenchymal involvement or involvement of the upper lobes and those that have associated pleural and parenchymal fibrosis. Other pleural and parenchymal fibrosis processes include asbestosis, connective tissue diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, and radiation- or drug-induced lung disease.7

The clinical context is fundamental for the adequate assessment of manifestations associated with pleural and parenchymal fibrosis (Fig. 4).

PPFE in a patient with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. (a) The transverse plane HRCT image at the level of the lung apices reveals irregular pleural and subpleural thickening (arrows). (b) In the coronal reconstruction plane, extensive pulmonary parenchymal involvement associated with hypersensitivity pneumonitis is observed, with retractile consolidations (blue arrows) and patchy areas of air trapping (red arrows). On the right lung apex, PPFE findings can be seen in the form of small images of subpleural retractile consolidation and pleural thickening (yellow arrows).

In chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis, a “pleural thickening” similar to that of PPFE can be observed. However, in this form of fungal infection, “pleural thickening” corresponds to a transient pleuroparenchymal hypersensitivity reaction and not to an irreversible fibrotic response of the pleura.38

Clinical course and prognosisThe clinical course of PPFE is variable and median survival is approximately 11 years. In some patients, progression can be very rapid, with a mean survival of three to five years.39

Several prognostic factors have been described in the clinical course of PPFE, including advanced age,40 male sex,41,42 the presence of dyspnoea,42 a low body mass index,43 the coexistence of interstitial lung disease or the presence of a UIP pattern in the lower lobes34,44,45 and the presence of pneumothorax46 (Fig. 5).

Severe PPFE. (a) Simple chest radiograph reveals multiple biapical retractile consolidations (arrows) with volume loss of the upper lobes. Post-surgical clips can be seen in the right axillary cavity. (b) Multiple subpleural fibrotic areas are observed bilaterally in HRCT. Note the presence of pronounced bilateral traction bronchiectasis (arrows) secondary to underlying pulmonary fibrosis. (c) Evolutionary radiograph reveals right apical pneumothorax (asterisks) associated with retraction of the fibrotic component of the lung (arrows).

Case courtesy of Dr Lydia Canales.

PPFE associated with a UIP pattern is a fatal and progressive disease, and its prognosis is significantly worse than that of patients with IPF.35 Most of these patients experience rapid disease progression, and five-year survival is between 23% and 58%.34,47 At present, no definitive results are available on the efficacy of antifibrotic drugs in the treatment of PPFE.48,49

ConclusionsThis article describes the different clinical, radiological, and pathological findings that characterise PPFE, its idiopathic form and the form associated with other entities; a better understanding of this entity will aid in its diagnosis.

Authorship- 1.

Person responsible for the integrity of the article: TF.

- 2.

Conception of the article: TF.

- 3.

Study design: not applicable.

- 4.

Data collection: not applicable.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: not applicable.

- 6.

Statistical processing: not applicable.

- 7.

Literature search: TF and AGP.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: TF and AGP.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: not applicable.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: TF and AGP.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.