The first-choice treatment for ileocolic intussusception is imaging-guided reduction with water, air, or barium. The objectives of the current study were to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided reduction of intussusception using water in patients under sedation and analgesia. We compare this approach with our previous experience in reduction using barium under fluoroscopic guidance without sedation and analgesia and investigate what factors predispose to surgical correction.

Material and methodsWe retrospectively reviewed cases of children with ileocolic intussusception treated in a third-level pediatric hospital during a 52-month period: during the first 24 months, reduction was done using barium and fluoroscopy without sedoanalgesia, and during the following 28 months, reduction was done using water and ultrasound with sedoanalgesia. A pediatric radiologist and a pediatrician reviewed the clinical history, surgical records, and imaging studies.

ResultsIn the 52-month period, 59 children (41 boys and 18 girls; mean age, 16.0 months) were diagnosed with ileocolic intussusception at our hospital. A total of 33 reductions (28 patients and 5 recurrences) were done using barium under fluoroscopic guidance, achieving a 61% success rate. A total of 38 reductions (31 patients and 7 recurrences) were done using water under ultrasound guidance with patients sedated, achieving a success rate of 76%. No significant adverse effects were observed in patients undergoing ultrasound-guided hydrostatic reduction under sedation, and the success rate in this group was higher (p = 0.20). The factors that predisposed to surgical reduction were greater length of the intussusception (p = 0.03), location in areas other than the right colon (p = 0.002), and a greater length of time between symptom onset and imaging tests (p = 0.08).

ConclusionUltrasound-guided hydrostatic reduction of ileocolic intussusception under sedoanalgesia is efficacious and safe.

La primera opción de tratamiento de la invaginación ileocólica es la reducción con agua, aire o bario guiada por imagen. Los objetivos de este estudio fueron evaluar la eficacia y seguridad de la desinvaginación usando agua guiada por ecografía bajo sedoanalgesia. La comparamos con nuestra experiencia previa con bario y guiada por fluoroscopia sin sedación e investigamos qué factores predispusieron a la corrección quirúrgica.

Material y métodosRevisión retrospectiva de niños con invaginación ileocólica tratados en un hospital pediátrico de tercer nivel en un periodo de 52 meses; los primeros 24 meses, los niños fueron sometidos a reducción fluoroscópica con bario sin sedación y los siguientes meses a reducción hidrostática ecoguiada con sedoanalgesia. Un radiólogo pediátrico y una pediatra revisaron la historia clínica, hojas quirúrgicas y estudios de imagen.

Resultados59 niños (41 niños y 18 niñas; edad media, 16,0 meses) fueron diagnosticados de invaginación intestinal en nuestro hospital en un periodo de 52 meses. Se realizaron 33 reducciones (28 pacientes y 5 recurrencias) guiadas por fluoroscopia usando bario, con una tasa de éxito del 61%. Treinta y ocho desinvaginaciones (31 pacientes y 7 recurrencias) utilizando agua, guiadas por ecografía bajo sedación, tuvieron una tasa de éxito del 76%. La tasa de éxito fue superior en el segundo grupo en el que se usó sedación (p = 0,20), sin que se detectaran efectos secundarios significativos. Los factores que predispusieron a la reducción quirúrgica fueron las invaginaciones de mayor longitud (p = 0,03), las que no se localizaron en colon derecho (p = 0,002) y en las que hubo un mayor intervalo desde el inicio de los síntomas a la prueba de imagen (p = 0,08).

ConclusiónLa reducción de la invaginación ileocólica guiada por ecografía usando agua y sedoanalgesia es una técnica eficaz y segura.

Ileocolic intussusception consists of intussusception (invagination or “telescoping”) of the terminal/distal ileum in the colon causing obstruction of the bowel lumen. It is the most common cause of bowel obstruction in children three months to three years of age, and requires emergency treatment to prevent ischaemia, necrosis and perforation of the affected loops.1

The first line of treatment is non-surgical in nature; in a procedure which is monitored via fluoroscopy or ultrasound, the radiology team introduces air, barium, water or normal saline through the rectum at a particular pressure to push back the head of the intussusception and eliminate the obstruction. Most centres in North America and the United Kingdom perform fluoroscopy-guided intussusception reduction using air. Elsewhere in Europe, there is a growing trend towards ultrasound-guided intussusception reduction using water or normal saline.2 Few studies have evaluated the effects of sedation in this field.3 The objectives of this study were to evaluate the safety and efficacy of ultrasound-guided intussusception reduction using water under sedation and analgesia compared to fluoroscopy-guided intussusception reduction using barium, and to investigate which factors predispose a patient to a need for surgical correction.

Materials and methodsA paediatric radiologist and a paediatrician retrospectively reviewed medical histories, surgery records, imaging studies and radiology reports for children who received care due to ileocolic intussusception at a tertiary paediatric hospital during a period of four years and four months (January 2015 to April 2019). In the first two years, fluoroscopy-guided intussusception reduction using barium without sedation was performed. After that, ultrasound-guided hydrostatic reduction with sedation was performed. A paediatric emergency physician administered sedation and analgesia with data recording.

Both imaging studies and intussusception reduction procedures were performed by the same group on duty, which included 10 paediatric radiologists and radiologists working with adults with experience on duty in paediatric radiology. Imaging findings and demographics, including sex, age, duration of symptoms, length and location of the intussusception, success of the procedure, and, if the intussusception could not be reduced, surgical findings, were reviewed. All sets of paired data were analysed using a two-tailed Student's t-test, which was either dependent or independent, as appropriate. Fisher's exact test was used to compare nominal variables between the surgery and non-surgery groups. Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, United States) was used for statistical analysis. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

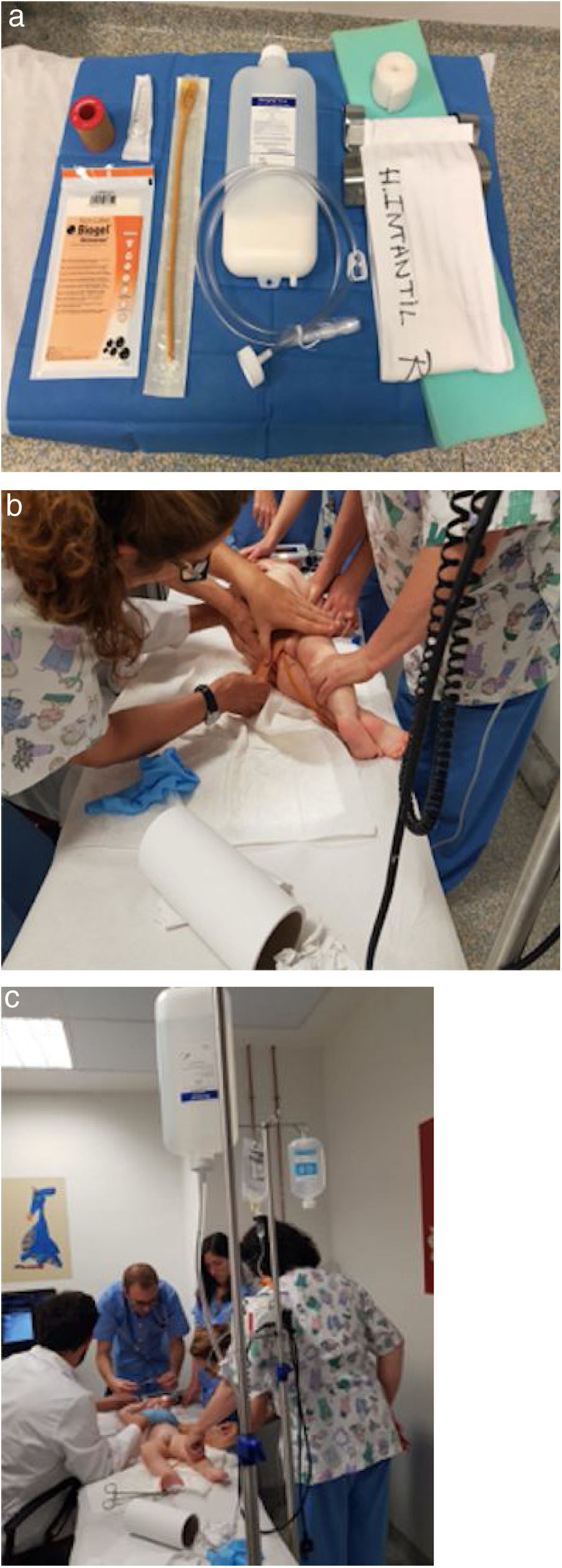

Ultrasounds were performed using a Canon Aplio 400 ultrasound system or a Siemens Acuson Antares ultrasound system with curvilinear and standard linear probes. Once ileocolic intussusception was confirmed on ultrasound, the nursing and radiology technician team prepared the materials (Fig. 1) and the room for the intussusception reduction procedure. The contraindications for attempting intussusception reduction were signs of intestinal perforation and signs of shock in the patient's physical examination.

A) Materials required for intussusception reduction (from right to left, adhesive tape, Foley catheter, bottle for filling with water/barium, tubes connecting the catheter and bottle to materials for sealing and materials for securing the boy for fluoroscopy). B) Nursing staff inserting the Foley catheter in the rectum, with the boy in the left lateral decubitus position. C) Radiologist to the right of the boy beside the ultrasound system, nursing staff to the left of the boy and paediatricians at the boy’s head, monitoring his vital signs. The bottle prepared for the start of the procedure has been filled with water and positioned at the foot of the bed at a height of approximately 1.5 m.

Procedural sedation and analgesia was performed by paediatric emergency physicians with specific training in this procedure. It was carried out according to an existing protocol on the paediatric emergency unit at our centre in accordance with the checklist and data collection protocol for procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. All patients had an assessment prior to the procedure that included: allergies, current medication, personal history, time since last meal and prior anaesthetic history. All patients also had an examination which focused on identifying potential difficulties in intubation that included cardiorespiratory auscultation and an assessment of aspiration risk.

Each patient underwent a pain assessment according to validated scales for different ages, and an anxiety assessment using the Groningen scale, to determine the type and dose of sedation and analgesia to be used.

The radiologist asked parents/guardians for specific informed consent prior to the intussusception reduction procedure and explained the procedure, possible complications and alternatives. The paediatrician asked for specific informed consent for procedural sedation and analgesia from the patients' parents/guardians. Procedural sedation and analgesia was not contraindicated in any of the patients in the sample.

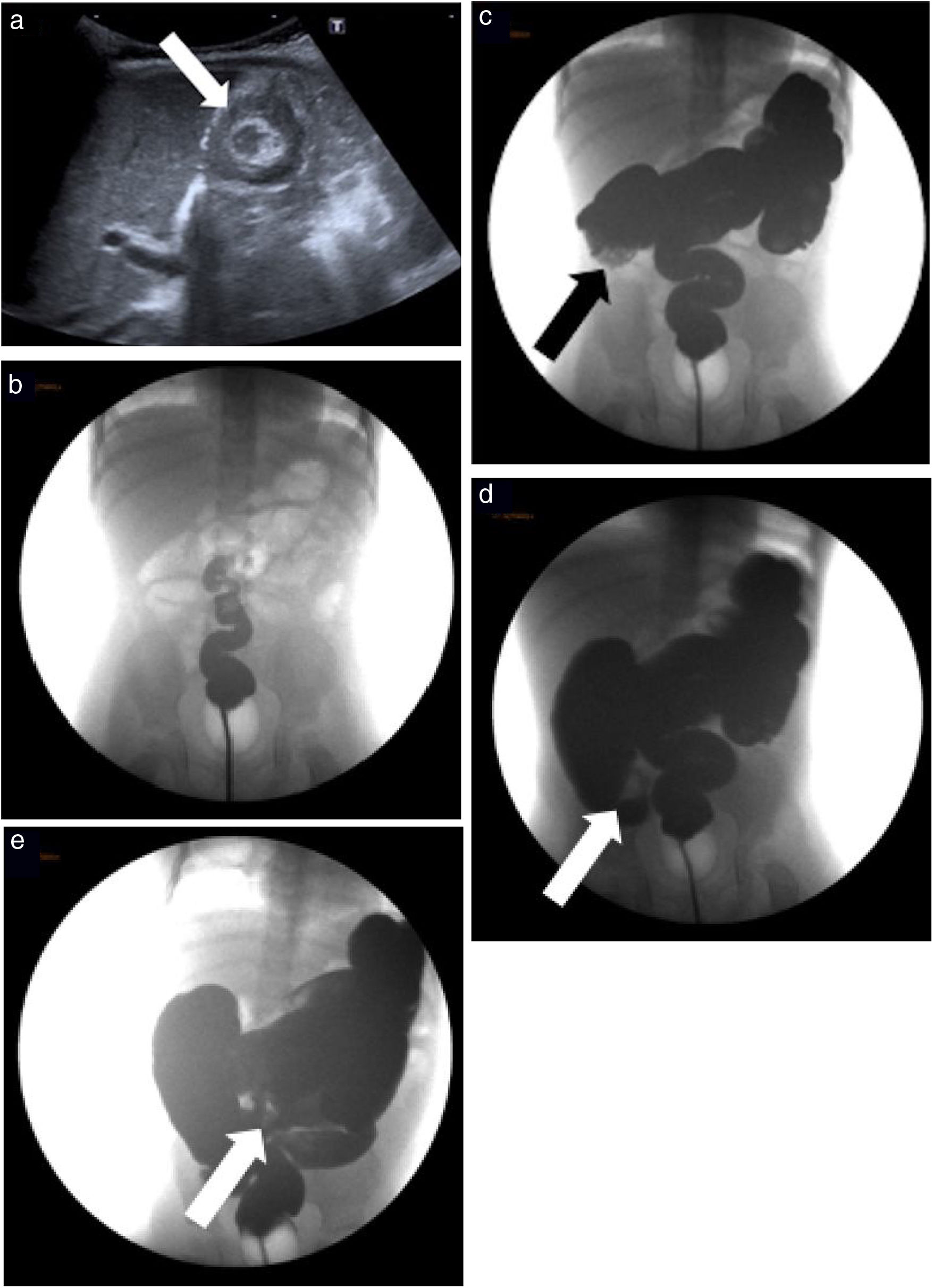

Prior to the procedure, the paediatric surgery department was notified and was present during the procedure whenever possible. At the start of the procedure, a Foley catheter was placed in the rectum (22−24 F, depending on the patient's size) and the balloon was inflated to keep the catheter in place. The rectum was sealed by taping the buttocks together with plenty of adhesive tape to prevent fluid/air leaks. The water and barium used in these procedures was at room temperature. In intussusception reduction with barium (Fig. 2), after the child was positioned on the table in the supine decubitus position, the bowel luminogram was evaluated using a scope, then contrast was introduced. Next, the system, placed at a height of approximately 1 m over the patient, was opened, the entire colon was filled by the force of gravity and the head of the intussusception was displaced towards the ileocaecal valve. The intussusception was considered to be resolved when barium reflux was observed at the terminal ileum. No sedation of any kind was used in fluoroscopy-guided intussusception reduction studies using barium.

A 9-month-old girl with a history of 6 h of abdominal pain. A) Ultrasound image showing ileocolic intussusception (arrow) in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. B) Frontal image obtained by fluoroscopy showing the catheter and the inflated balloon in the rectum and the contrast filling the rectum. C) The contrast has filled the entire colic area, thus delineating the head of the intussusception (arrow) in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. D) The contrast has pushed the head of the intussusception (arrow) towards the right iliac fossa. E) The intussusception has resolved; contrast is seen to reflux in the distal ileum (arrow).

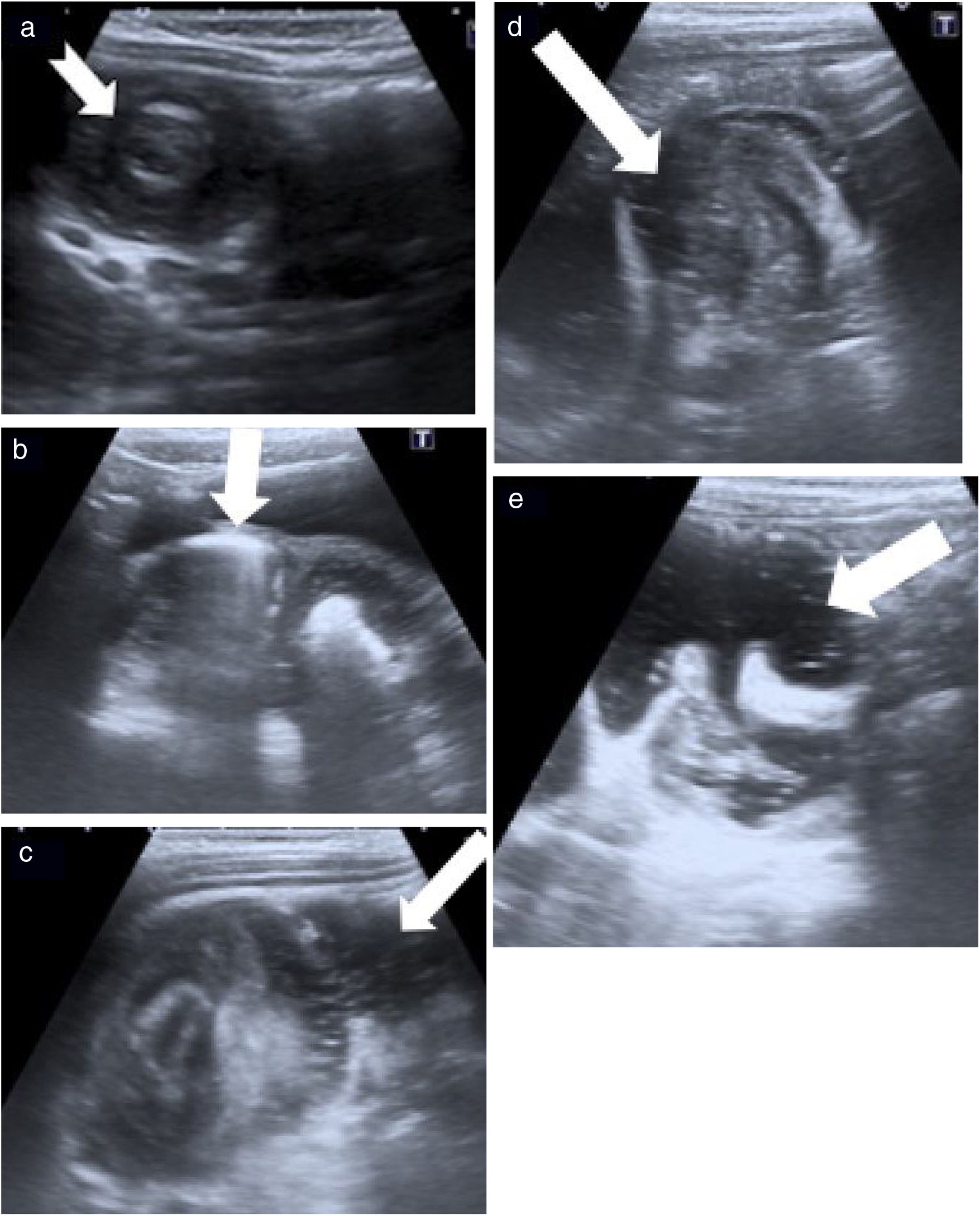

In intussusception reduction procedures with water (Fig. 3), the intussusception reduction process was started with the ultrasound probe placed on the pelvis to visualise the passage of water through the rectum and sigmoid colon. Subsequently, the column of water was followed until it came into contact with the head of the intussusception and the process was followed until refluxing water was identified at the terminal ileum.

A 2-year-old boy with a history of 4 h of abdominal pain and blood in faeces. A) Ultrasound image showing intussusception (arrow) in the right iliac fossa. B) After the catheter is inserted in the rectum and the balloon is inflated, the system is opened and the water is confirmed to enter and distend the rectum (arrow). C-D) The water has reached, and is seen to push, the head of the intussusception (arrows). E) The intussusception has resolved; water is seen to reflux in the terminal ileum with slight thickening of the wall of the ileocaecal valve (arrow).

When the first attempt at intussusception reduction failed, up to two more attempts were made. The duration of each attempt was approximately three to five minutes and the lapse of time between each attempt was around 30 min. Following completion of the procedure with barium or water, as much water/barium as possible was removed from the colon and the absence of signs of perforation was confirmed.

In all cases of intussusception reduction with water, procedural sedation and analgesia was used; the aim was to achieve a moderate level of sedation (measured with the University of Michigan sedation scale) and render the patient sleepy or asleep, yet easily awoken with tactile stimulation or verbal commands.

The pharmacological options used in our patients were intravenous administration of midazolam as a sedative (0.05−0.1 mg/kg/dose) plus fentanyl (0.5−1 μg/kg/dose) or ketamine (0.5−1 mg/kg/dose). Patients in whom a peripheral venous line could not be placed were administered intranasal midazolam (0.2−0.3 mg/kg/dose) via an atomiser plus fentanyl (1−3 μg/kg/dose) or intranasal ketamine (2−3 mg/kg/dose).

Patients were monitored before, during and after the procedure. They underwent continuous pulse oximetry, non-invasive capnography, monitoring of the degree of sedation and determination of blood pressure every five minutes.

After the procedure, the patient was transferred to the emergency observation area, where clinical surveillance and monitoring continued until the patient recovered from the sedation and analgesia. All the patients who underwent satisfactory intussusception reduction were kept under observation for approximately 24 h, to watch for any potential early recurrence.

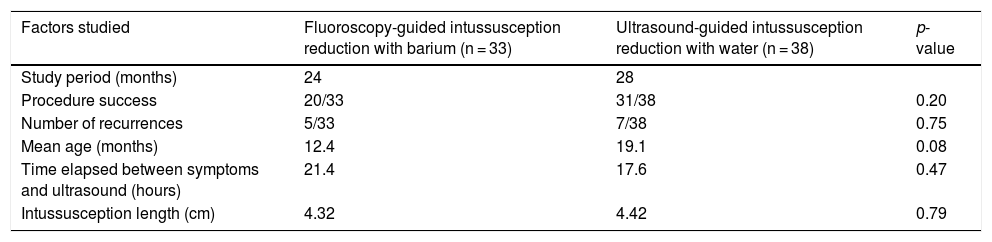

ResultsFifty-nine children were diagnosed at our hospital with ileocolic intussusception in a 52-month study period. Twenty-eight children (21 boys and 7 girls; mean age at presentation: 12 ± 6 months) were diagnosed in the 24-month period in which fluoroscopy-guided reduction using barium was performed, and 31 children (20 boys, 11 girls, mean age at presentation: 19 ± 20 months) were diagnosed in the subsequent 28-month period. Table 1 compares these two techniques.

Comparison of fluoroscopy-guided ileocolic intussusception reduction with barium to ultrasound-guided reduction with water.

| Factors studied | Fluoroscopy-guided intussusception reduction with barium (n = 33) | Ultrasound-guided intussusception reduction with water (n = 38) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study period (months) | 24 | 28 | |

| Procedure success | 20/33 | 31/38 | 0.20 |

| Number of recurrences | 5/33 | 7/38 | 0.75 |

| Mean age (months) | 12.4 | 19.1 | 0.08 |

| Time elapsed between symptoms and ultrasound (hours) | 21.4 | 17.6 | 0.47 |

| Intussusception length (cm) | 4.32 | 4.42 | 0.79 |

Thirty-three fluoroscopy-guided reductions using barium were performed, with a success rate of 61% (20 out of 33). Twenty-eight corresponded to initial diagnoses and five corresponded to recurrent intussusception. The mean time elapsed from presentation of symptoms to ultrasound was 21 h. The head of the intussusception was located in the right colon in 25 cases (76%), the transverse colon in three cases, the left colon in five cases and the rectosigmoid junction in one case. The reduction was successful in 20 out of 33 cases (61%), with five recurrences (15%).

Thirty-eight ultrasound-guided intussusception reduction procedures with water were performed in the second group of 31 patients, with a success rate of 76% (29 out of 38). Intussusception recurred in seven (18%) cases. The mean time elapsed between onset of symptoms and ultrasound was 18 h. At the time of the ultrasound, the head of the intussusception was located in the right colon in 32 (84%) cases, the transverse colon in four cases and the rectum in two cases. This group was administered sedation by paediatric emergency physicians as described in the technique. The only side effect seen following procedural sedation and analgesia was vomiting in four out of 31 (12.4%) patients. It should be borne in mind that some patients already presented vomiting as a clinical sign of intussusception prior to the procedure (17 out of 31 patients [54%]). There were no complications following procedural sedation and analgesia.

The success rate in non-surgical ileocolic intussusception reduction increased from 61% to 76% after sedation started to be used; this increase was not statistically significant (p-value 0.20). The recurrence rate was similar in the two groups, around 15% (p-value 0.75). No statistically significant differences were found between the two techniques.

No signs of perforation were detected on imaging tests or in surgery in any of the study patients. In one of the cases in the second group in which intussusception reduction could not be performed, signs of intestinal wall ischaemia were identified during surgery. In one case, acute appendicitis was identified as an underlying cause of intussusception.

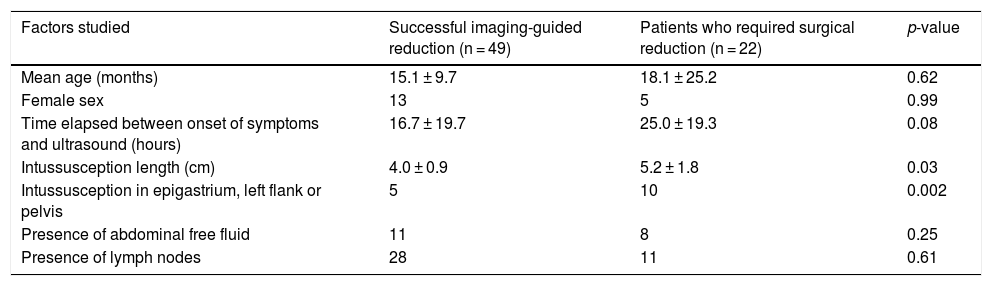

The groups in which the intussusception reduction manoeuvre was successful (n = 49) were statistically compared to the group that required surgery (n = 22) (Table 2) in search of factors that might predict which patients would require surgery. Intussusceptions of a longer length (p-value 0.03) and intussusceptions in which the head was not in the right colon (p-value 0.002) were associated with a higher rate of surgical reduction. Intussusceptions subjected to surgical reduction presented a longer period from onset of symptoms to ultrasound than those subjected to imaging-guided reduction (16.7 versus 25.0 h, p-value 0.08). No statistically significant relationship was found between patient age (p-value 0.62), presence of lymph nodes (p-value 0.61) or intra-abdominal free fluid (p-value 0.25) and need for surgery in these patients.

Comparison of factors that may influence successful ileocolic intussusception reduction with barium or water monitored with imaging techniques versus patients who required surgical intervention.

| Factors studied | Successful imaging-guided reduction (n = 49) | Patients who required surgical reduction (n = 22) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (months) | 15.1 ± 9.7 | 18.1 ± 25.2 | 0.62 |

| Female sex | 13 | 5 | 0.99 |

| Time elapsed between onset of symptoms and ultrasound (hours) | 16.7 ± 19.7 | 25.0 ± 19.3 | 0.08 |

| Intussusception length (cm) | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 5.2 ± 1.8 | 0.03 |

| Intussusception in epigastrium, left flank or pelvis | 5 | 10 | 0.002 |

| Presence of abdominal free fluid | 11 | 8 | 0.25 |

| Presence of lymph nodes | 28 | 11 | 0.61 |

The treatment of choice in ileocolic intussusception is reduction with an air or liquid enema guided by imaging tests.4 Types of enema and diagnostic imaging have varied over the years, but the concept remains the same: the head of the intussusception is pushed until liquid or air monitored with real-time imaging is seen to reflux through the ileocaecal valve. Since 2017, our department has performed ultrasound-guided hydrostatic reduction aided by sedation and analgesia administered by paediatric emergency physicians, to reduce radiation in this population and in view of the growing experience of multiple centres that supported this technique.

We believe that the improved rate of reduction that we saw in this period resulted from the use of procedural sedation and analgesia in the second study group. The effect of sedation in intussusception reduction is not well studied and remains a matter of debate. Some studies have shown lower rates of reduction,5 whereas others have found a higher success rate with the use of sedation.6,7 The use of propofol has yielded excellent results8; glucagon has proven ineffective.9,10 Our experience since we started using a combination of midazolam plus ketamine or plus fentanyl has been very positive, without medication-related complications. Other advantages of the use of procedural sedation and analgesia in this scenario are decreased study duration and decreased discomfort during the study.

The positive effect of sedation due to muscle relaxation and decreased extraluminal abdominal pressure has been reported and is known, and, in our experience, 10–14% of cases of intussusception that could not be reduced by the radiology team on arrival at the operating theatre following administration of anaesthesia had disappeared on inspection by the surgeon.11

Multiple studies in the specialised literature comparing reduction with air and with liquid (barium, iodinated contrast, normal saline or water) have shown reduction with air to be significantly superior, with a success rate of 82% in air reduction versus 68% in all other techniques. The success of air reduction compared to hydrostatic reduction is due to higher intraluminal pressure in air reduction.12 Hadidi et al.13 conducted a randomised controlled study in which they compared hydrostatic to ultrasound-guided reduction, reduction with air and fluoroscopy-guided reduction with barium. They found no significant differences with regard to age, sex or duration of symptoms. The percentage of success was higher in reduction with air (90%) than in ultrasound-guided hydrostatic reduction (67%) or in fluoroscopy-guided reduction with barium (70%). Our results were similar to those reported by these articles, 61% using fluoroscopy-guided reduction with barium and 76% using ultrasound-guided reduction with water. Our study used water rather than normal saline, as it is cheaper and more accessible. Normal saline is a reliable, harmless option and the one most extensively reported in the literature14; it may be preferable in young children so as not to interfere with the hydroelectrolytic balance. However, our study, as well as another article,15 reported no complications associated with using water.

Various studies have shown that factors such as age, rectal bleeding, radiological signs of bowel obstruction and a longer duration of signs and symptoms decrease the success rate.16–21 Our study confirmed that a long period of time between onset of symptoms and ultrasound, longer intussusception length and location of the head of the intussusception outside the right colon are signs associated with a need for surgical reduction. Even so, none is an absolute contraindication to attempting reduction if the patient is clinically stable and well-hydrated.4

Rates of recurrence are 8–15% with the use of barium enemas and 5–20% with the use of water enemas4; these figures are similar to that seen in our cohort of patients, in which both techniques had a recurrence rate close to 15%. Two series of patients have shown a high rate of reducibility among recurrent cases; hence, at our hospital, we repeat the intussusception reduction procedure if the patient is clinically stable.11,22

The most serious complication of intussusception is perforation of the bowel loops, with a mean reported rate of 0.8%12; this rate is similar whether liquid or air reduction is used. Our study did not find any cases of perforation. However, any case of perforation in an air enema is very serious, as it may result in tension pneumoperitoneum compressing the diaphragm and causing cardiorespiratory arrest. Due to the safety and efficacy of intussusception treatments, the mortality rate is extremely low: 2.1 per million live births.23

Our study corroborated the predominance of ileocolic intussusception in males, with a ratio of approximately 2:1.24 Ileocolic intussusception is idiopathic and a lead point is rarely identified. In our study, a lead point was identified in one out of 59 patients.4 Today, idiopathic intussusception is attributed to mesenteric lymph nodes which trigger intussusception as part of a viral infection.

The main limitation of this study was the fact that it was impossible to compare the two intussusception reduction techniques described, as one did not involve the use of anaesthesia. Its other limitations included its retrospective, single-centre nature and the fact that the significance of the study could not be evaluated with Doppler ultrasound of the vascularisation of the loops, as it had not been performed in all studies, or at least had not been uniformly collected in images and/or reports.

A randomised, multi-centre, prospective study comparing the different techniques used under the same conditions must be conducted. Vázquez et al.25 have reported a very promising technique for non-surgical reduction of intussusception using external manual compression and intermittent visualisation on ultrasound, with a reduction rate of approximately 80%, neither causing perforation nor involving the use of ionising radiation, thus enabling patients to recover quickly.

ConclusionUltrasound-guided reduction of ileocolic intussusception with air or normal saline and sedation and analgesia is a safe and effective technique for the non-surgical treatment of ileocolic intussusception. Our intussusception reduction success rate has increased since we started using this radiation-free technique, without us having detected significant complications. With this article we wish to encourage more centres to start using this harmless, effective technique and to promote administration of sedation and analgesia for this emergency procedure.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Caro-Domínguez P, Hernández-Herrera C, Le Cacheux-Morales C, Sánchez-Tatay V, Merchante-García E, Vizcaíno R, et al. Invaginación ileocólica: reducción hidrostática ecoguiada con sedoanalgesia. Radiología. 2021;63:406–414.

This study was presented orally at the 55th Annual Meeting of the European Society of Paediatric Radiology in Helsinki, Finland, in June 2019.