Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus. Endometriosis of the bowel and urinary tract are types of extragenital endometriosis that manifest with nonspecific symptoms, but their detection involves specific therapeutic strategies. Although the characteristics of the disease on transvaginal ultrasonography and on magnetic resonance imaging have been described in many publications, few references describe its characteristics on abdominal ultrasonography.

This paper illustrates the findings for infiltrating endometriosis involving the bowel and urinary tract on abdominal ultrasonography and shows the usefulness of this technique for identifying signs of the disease that have been described with other techniques. Knowledge of infiltrating endometriosis and its ultrasonographic features will enable radiologists to suggest its diagnosis and to include it in the differential diagnosis of pelvic pain in women of child-bearing age.

ConclusionAbdominal ultrasonography is a useful tool in the diagnosis of extragenital endometriosis. Familiarity with the ultrasonographic appearance of this entity facilitates the diagnostic orientation and management of patients with pelvic pain.

La endometriosis es la presencia de tejido endometrial fuera del útero. La endometriosis intestinal y del tracto urinario son formas de endometriosis extragenital que se manifiestan con síntomas inespecíficos, pero su detección conlleva estrategias terapéuticas específicas. Las características de la enfermedad se han descrito con ecografía transvaginal y resonancia magnética en numerosas publicaciones, pero existen escasas referencias de ecografía abdominal.

El objetivo de este trabajo es ilustrar los hallazgos ecográficos de la endometriosis infiltrante (intestinal y del tracto urinario) desde el abordaje abdominal y mostrar su utilidad en reconocer signos de la enfermedad previamente descritos con otras técnicas. Conocer la enfermedad y sus características ecográficas permite al radiólogo sugerir su diagnóstico e incluirla en el diagnóstico diferencial del dolor pélvico en mujer en edad fértil.

ConclusiónLa ecografía abdominal constituye una herramienta útil en el diagnóstico de la endometriosis extragenital. La familiarización con sus apariencias ecográficas facilita la orientación y manejo de este tipo de pacientes.

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity and myometrium.1,2 When the endometrial implant penetrates the peritoneum at a depth of more than 5mm, it is considered deep pelvic endometriosis or deep infiltrating endometriosis.2–6 Lesions are typically found in the pelvis, including the ovaries, but can appear in multiple sites and are associated with reactive inflammation, fibrosis, adhesions and smooth muscle hyperplasia. Extragenital infiltrating endometriosis refers to such implants in other parts of the body, including the gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, liver, pancreas, spleen, lungs, limbs, skin and nervous system.4 Extragenital endometriosis is rare; it occurs in approximately 8%–12% of women with endometriosis,5 most often in the gastrointestinal and urinary tract.

Ectopic endometrial tissue and the resulting inflammatory response can cause dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, chronic pain and infertility.1–7 A rare but serious sign of ileocaecal endometriosis in young women is recurrent small bowel obstruction. As the symptoms tend to be nonspecific, the delay in diagnosis is estimated to be several years.

Laparoscopy remains the gold standard for the definitive diagnosis and staging of endometriosis.2,3 Diagnostic imaging is based on the morphological characteristics of the lesion and the presence of blood content. Transvaginal ultrasound is the first-line imaging method.1–9 However, there are no previous publications on the findings and utility of abdominal ultrasound. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can identify and characterise the lesion, thanks in particular to the presence of blood degradation products.3,4,6

The objective of this study is to describe and illustrate ultrasound findings in infiltrating endometriosis from an abdominal approach and to show its utility in identifying characteristic signs of the disease reported with other imaging techniques, such as endocavity ultrasound or MRI. Recognition of these findings may help guide the diagnosis of this condition and aid the radiologist in the differential diagnosis of the many causes of pelvic and abdominal pain in women of childbearing potential.

Remember that: transvaginal ultrasound is the first-line imaging method in the diagnosis of endometriosis. However, as the clinical diagnosis is complex, abdominal ultrasound is sometimes the first-line diagnostic test.

Role of diagnostic imaging in endometriosisUltrasound is the leading imaging method in diagnosing endometriosis due to its availability and resolution.2–8 When ultrasound results are inconclusive or there is extensive involvement, MRI is preferred.2–,6,7

Endocavity ultrasound (transvaginal and endorectal).Transvaginal ultrasound is the best initial diagnostic tool.2–9 Although not essential, suitable bowel preparation and the use of endorectal ultrasound gel can improve visualisation of intestinal implants.3,7–12 The rectum and sigmoid colon, rectovaginal septum, uterosacral ligaments, uterus, adnexa, recto-uterine pouch, bladder and ureters should all be assessed.

Endorectal ultrasound can be performed when the vaginal approach is not possible, and allows for ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) puncture/biopsy of the lesion.1

The main limitation of endocavity ultrasound in the diagnosis of endometriosis is that it underestimates the extent of the disease, due to its limited assessment of the bowel segments proximal to the rectosigmoid junction and the difficulty in determining the degree of infiltration (implant depth).3,7,9

Abdominal ultrasound is often the first imaging technique used when there is little clinical suspicion of endometriosis, especially when assessing chronic abdominal pain in young women or when gynaecological ultrasound is inconclusive. Abdominal ultrasound has traditionally been considered not very accurate in detecting endometriosis, mainly due to the presence of intestinal gas and the deep pelvic location of the lesions.9 However, except for the rectum, most regions it affects are accessible using the abdominal approach: sigmoid colon, terminal ileum, caecum and appendix. Therefore, signs of intestinal endometriosis proximal to the rectosigmoid junction can be identified, as can associated findings, such as dilation of bowel loops and free intraperitoneal fluid when there are obstructive symptoms secondary to the disease. It is also the preferred technique in the study of the upper urinary tract for identifying obstructive uropathy due to bladder and/or ureteral endometriosis lesions.4,9

Computed tomography (CT) is reserved for clinical scenarios featuring obstructive symptoms or haematochezia. In contrast CT, endometriosis may be indistinguishable from other gastrointestinal disorders, including benign or malignant neoplasms. These patients generally have to undergo a surgical examination (laparotomy or laparoscopy) with insufficient preoperative planning.3

MRI is preferred when assessing deep infiltrating endometriosis due to its high sensitivity in detecting blood degradation products and its ability to assess all pelvic structures. Therefore, MRI is reserved for cases in which deep pelvic involvement is suspected, in which it enables complete mapping of pelvic lesions, and for cases with an ultrasound diagnosis of deep endometriosis for preoperative assessment.2–4,6,7

Remember that: MRI is the technique of choice when assessing deep infiltrating endometriosis, as it enables assessment of all pelvic structures and therefore is ideal for preoperative planning.

Ultrasound findings in infiltrating endometriosisIntestinal endometriosis is the most common form of extragenital infiltrating endometriosis (12%–37% of patients with endometriosis), and the rectosigmoid junction is the most commonly affected area.13 It is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma in the bowel wall, inducing smooth muscle hyperplasia and fibrosis.3,6–8 This results in bowel wall with thickening varying degrees of stricturing. The foci of endometriosis adhere to the antimesenteric border of the bowel wall serosa. They gradually invade the serosal surface and infiltrate through the muscularis propria.3 Involvement may be isolated or multifocal (multiple lesions affecting the same segment) and/or multi-site (multiple lesions affecting several bowel segments, such as the small intestine, large intestine, caecum, ileocaecal junction and/or appendix).8

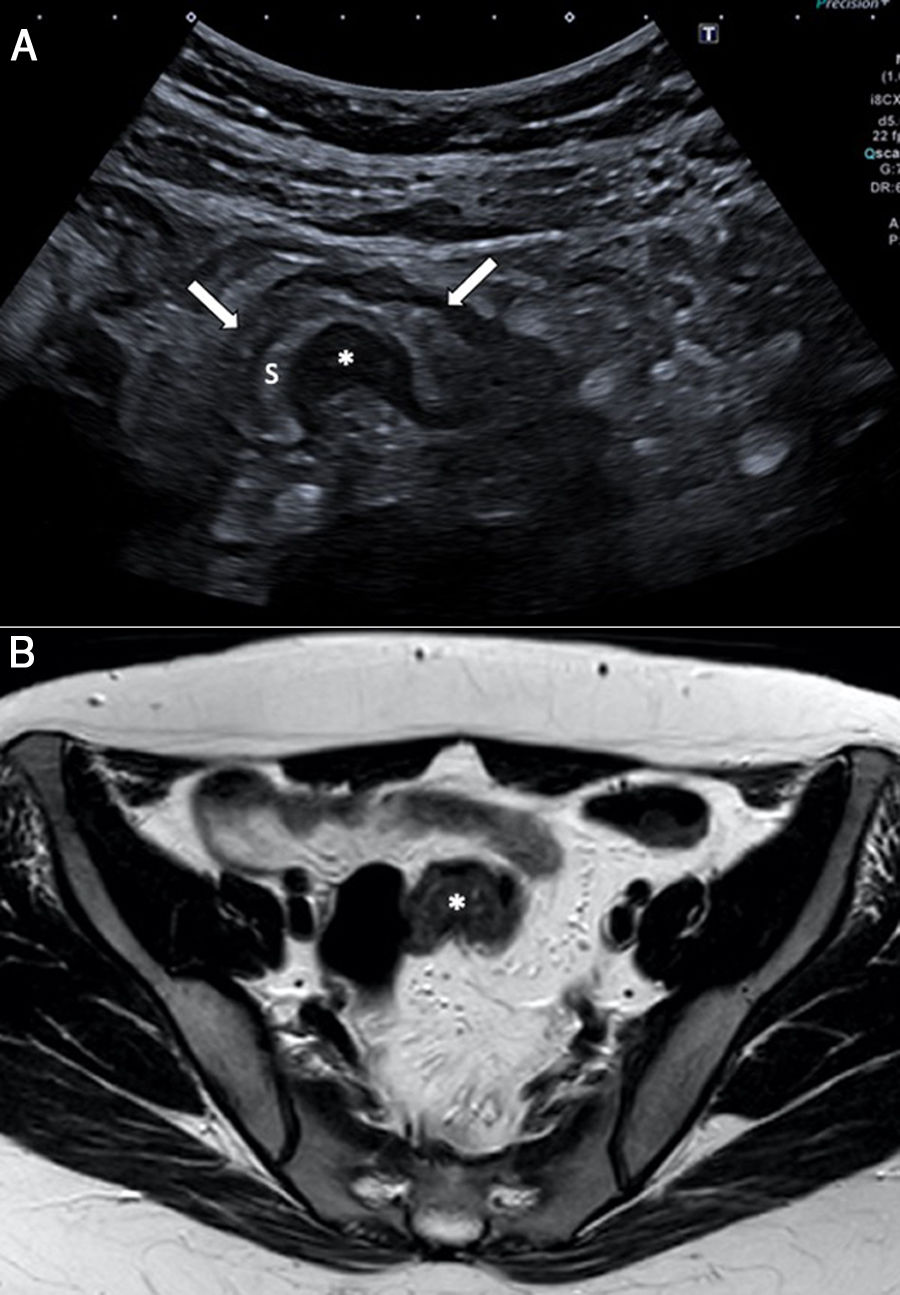

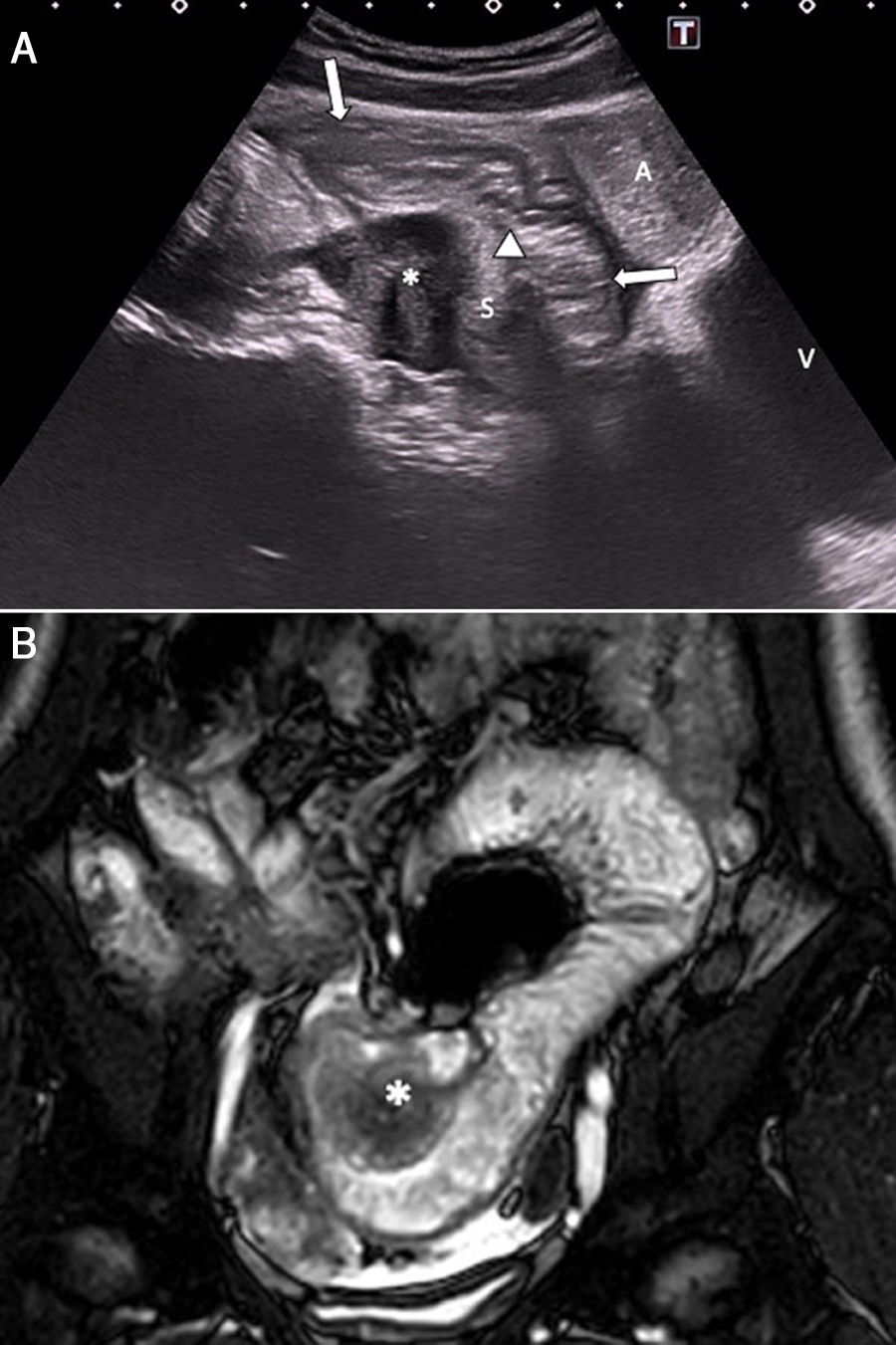

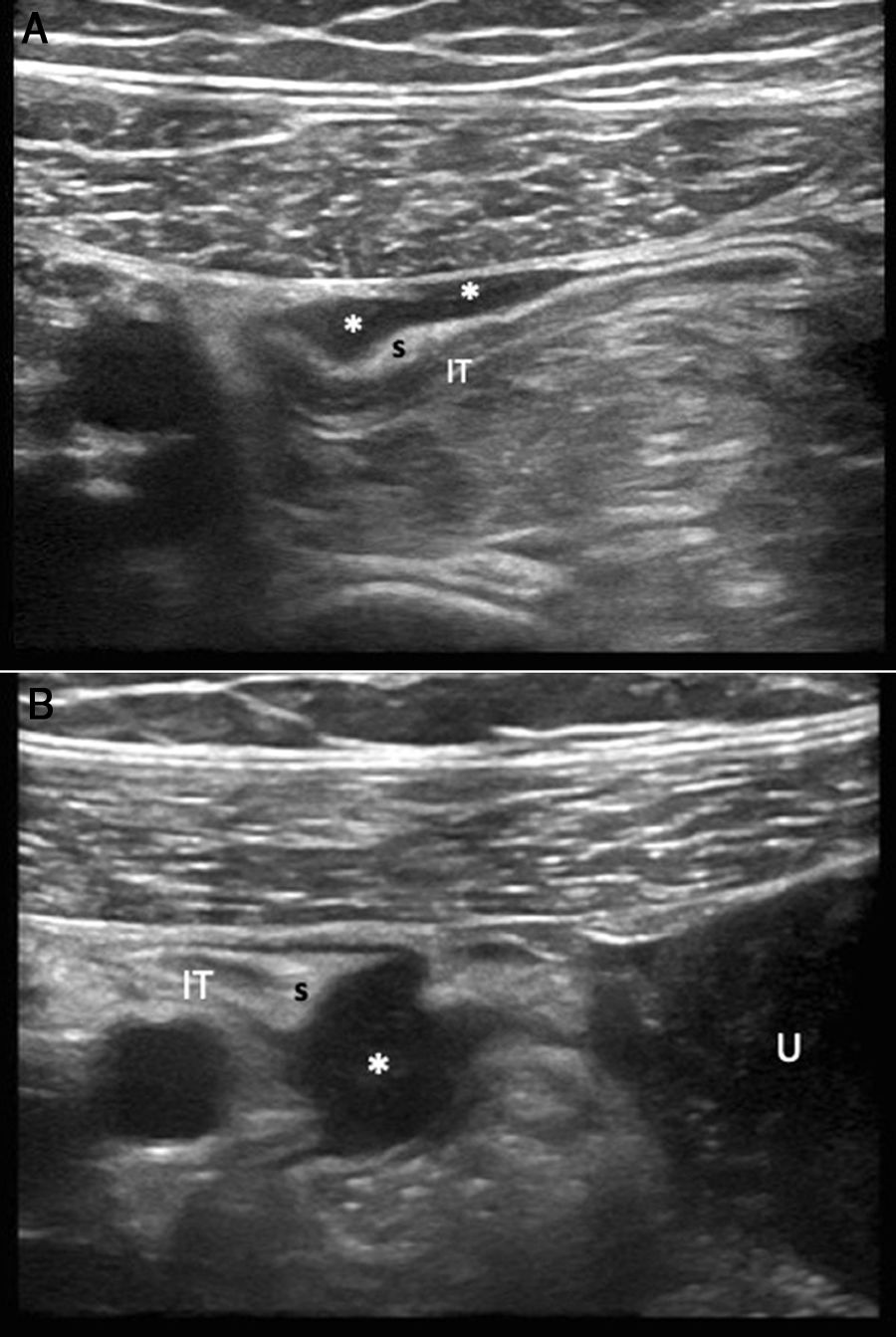

The appearance of endometriosis on ultrasound is variable. It is determined by the nature of the endometriotic foci, which are often nodular (secondary to reactive fibrosis) or cystic (secondary to bleeding); the size of the foci; and the presence of adhesions. They often consist of hypoechoic lesions, which penetrate the muscularis propria; as such, they can easily be distinguished from the adjacent structures, such as abdominal fat and layers of the bowel wall (Figs. 1 and 2). At other times, due to the presence of internal echoes, they have mixed content; more rarely, they can appear hyperechoic or cystic.3 They can also be seen as hypoechoic lesions of laminar morphology along the bowel wall. Implants do not show significant flow with Doppler colour ultrasound.1–12

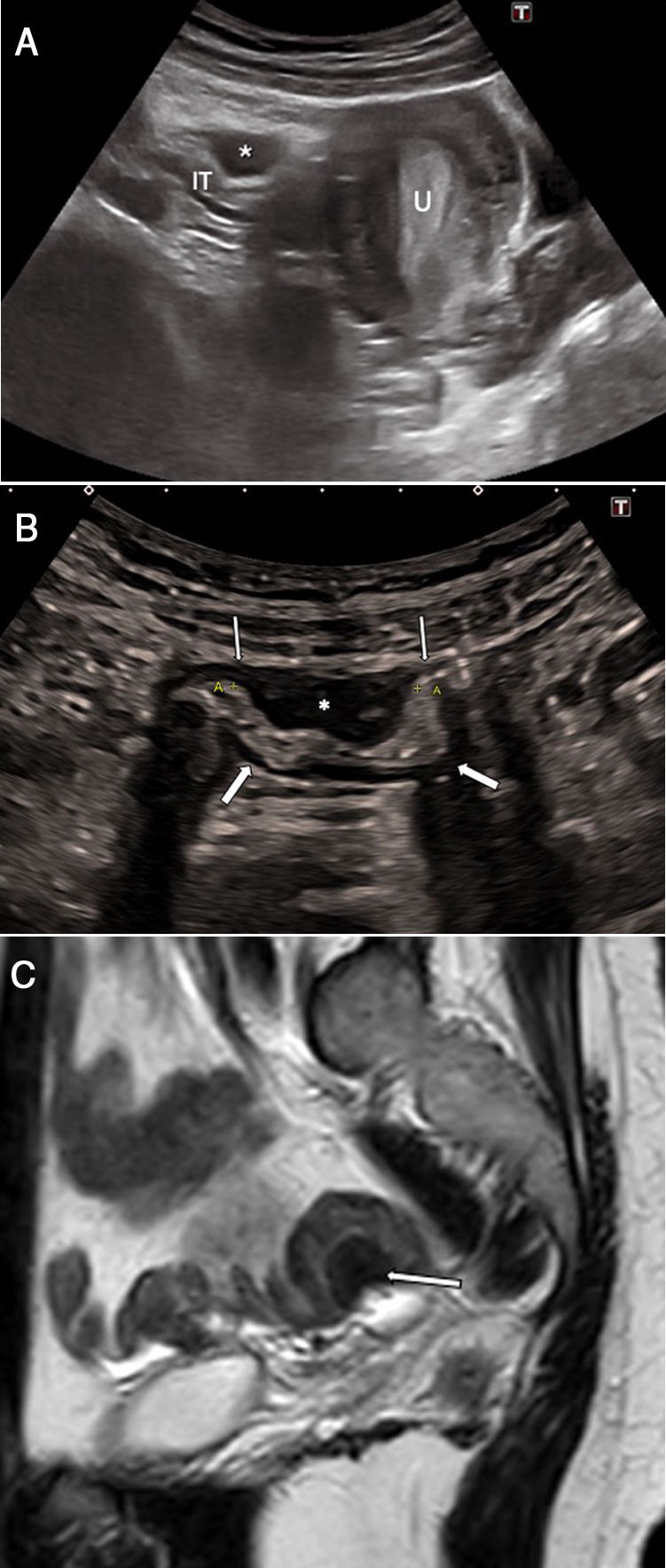

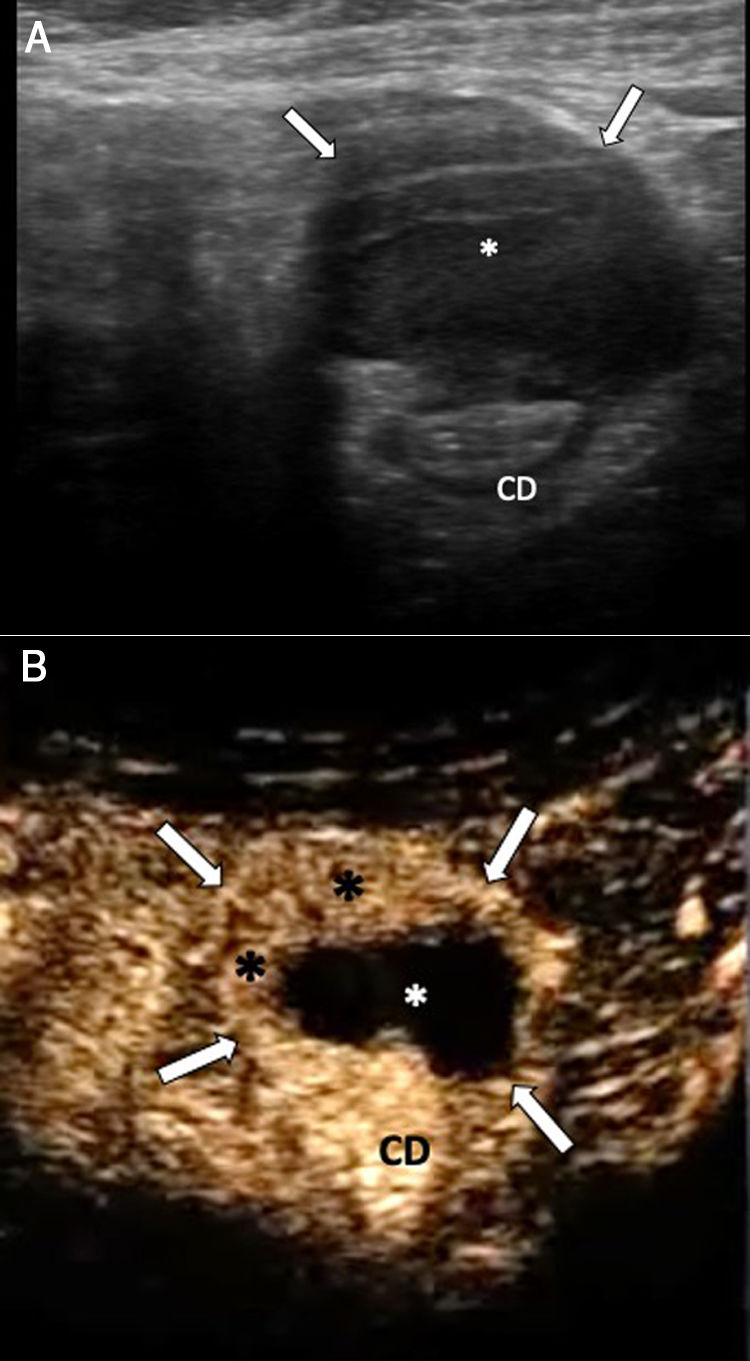

A 27-year-old woman with hypogastric pain not improving with usual analgesia. A) Abdominal ultrasound shows a hypoechoic nodule (*) attached to the wall of the sigmoid colon which is penetrating into the muscularis propria with growth towards the submucosa (S), causing the lumen to collapse (arrows). B) The study using pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (transverse T2-weighted turbo spin echo [TSE] image) confirms a lesion with a nodular morphology (*) in the sigmoid colon wall, with growth towards the submucosa and hyperintense foci inside suggestive of glandular tissue. The patient required surgery and the pathology confirmed intestinal endometriosis.

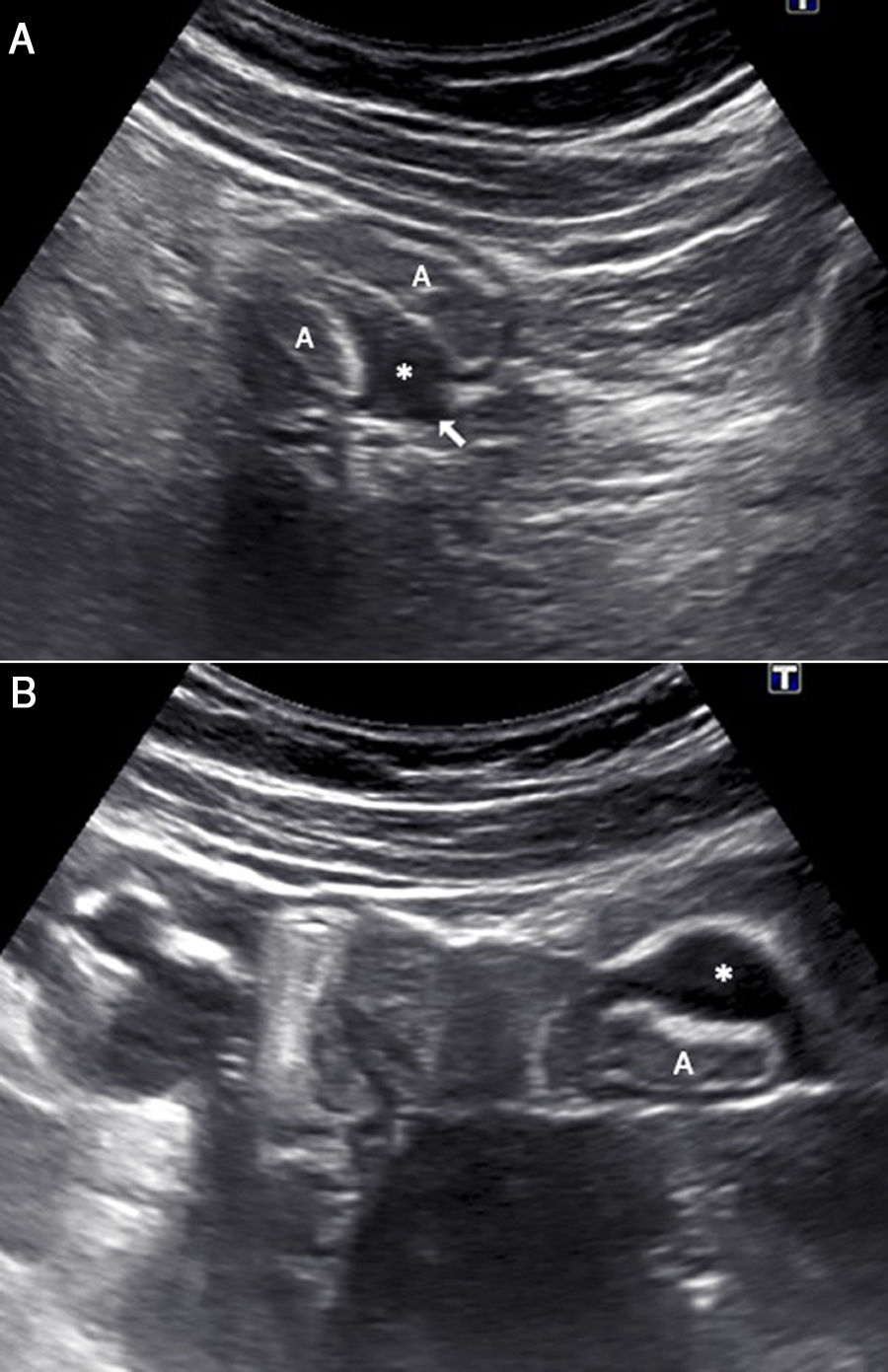

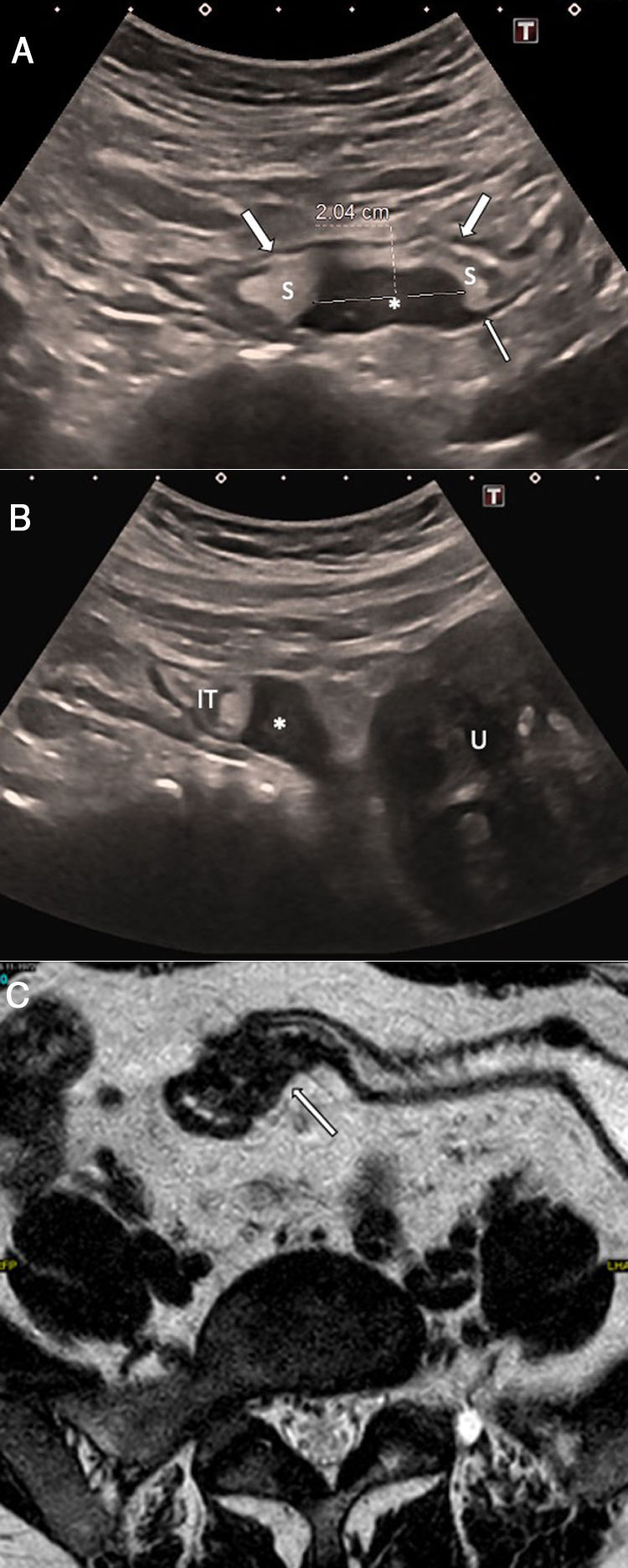

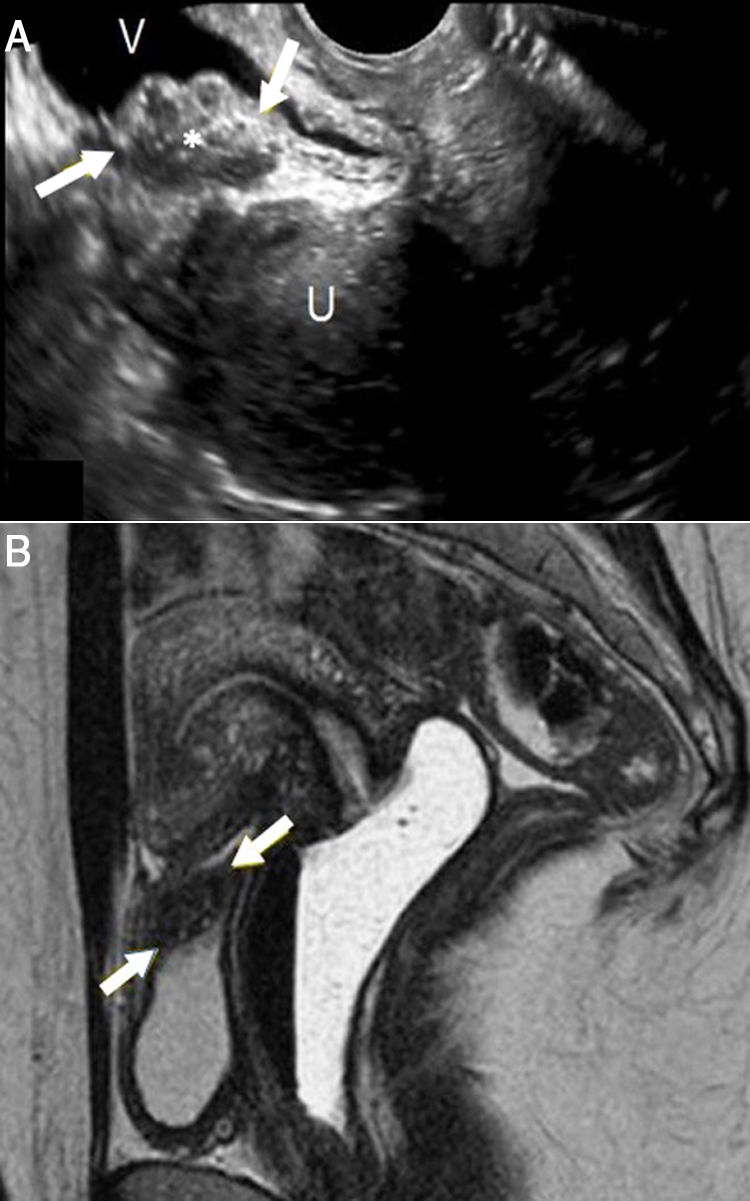

A 36-year-old woman with nausea and continuous abdominal pain, unrelated to ingestion or defecation, for the past 3 weeks. A) Abdominal ultrasound shows a hypoechoic lesion with a nodular morphology (*) adjacent to a loop of small intestine, eccentric growth from the serosa to the submucosal layer (S), which is compressing the intestinal lumen (arrows) and dilating the bowel loops (A) proximal to the stricture. Irregularities (arrowhead) in the hyperechoic submucosal layer are indicative of endometriosis infiltration. B) Magnetic resonance imaging (T2-weighted TSE coronal image) confirms the findings, identifying an eccentric lesion with endophytic growth (*) causing the dilation of loops of small intestine. The pathology examination showed endometrial tissue. V: bladder.

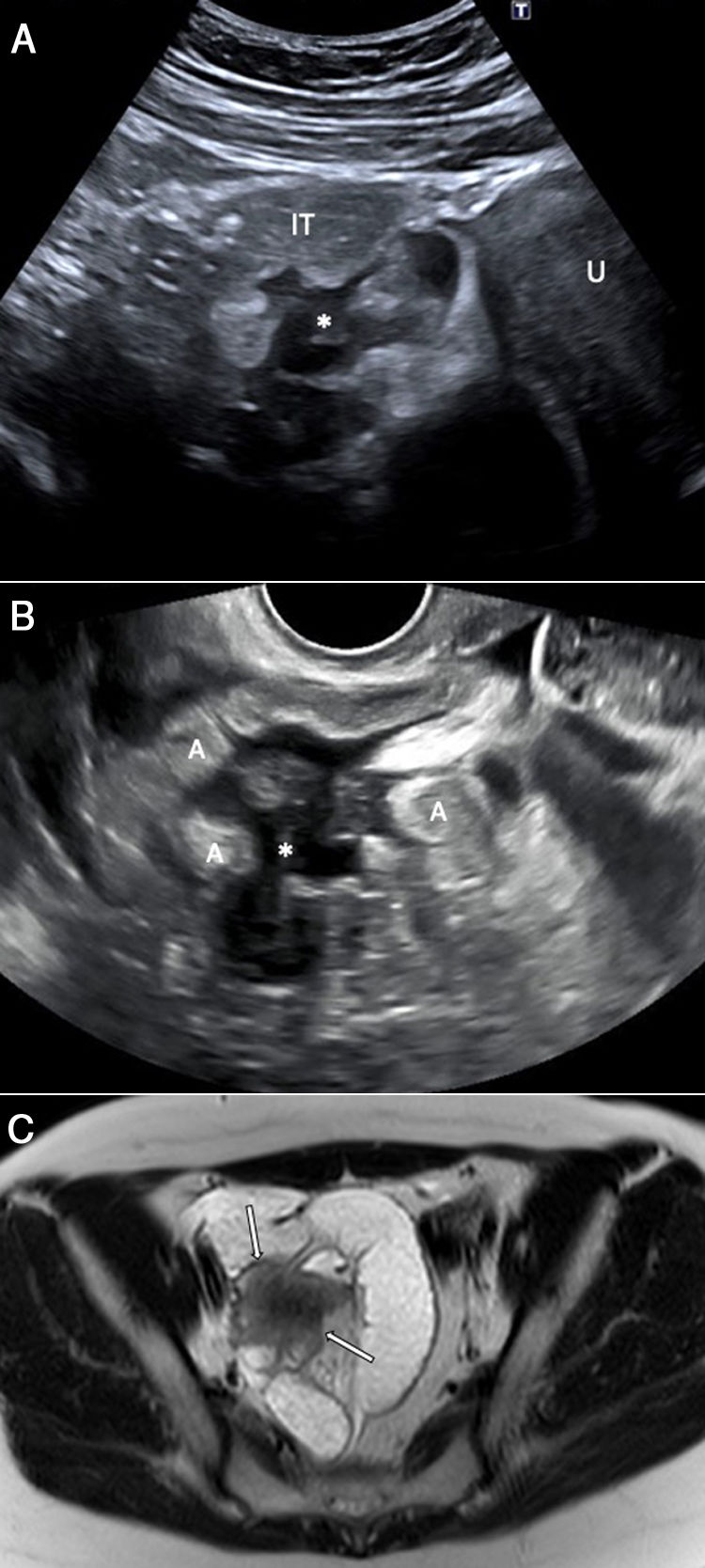

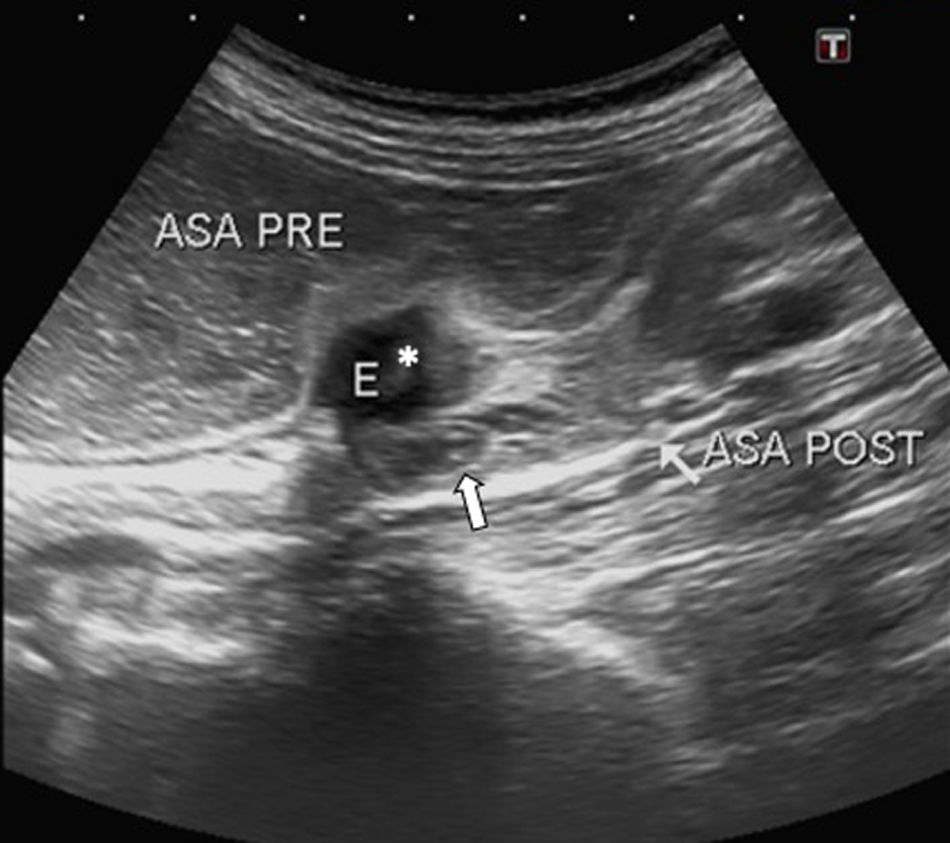

Use of high-frequency transducers enables accurate identification of the bowel wall’s layer structure: the muscularis propria is hypoechoic, and the submucosa is echogenic (Fig. 3).1,14 There is very little in the literature on the appearance on ultrasound of intestinal endometriosis. It usually appears as a hypoechoic nodule or thickening of the muscularis propria, with variable morphology and margins (Fig. 4).10,15 The normal appearance of the muscularis propria of the bowel is replaced by a nodule of abnormal tissue with possible retraction and adhesions (Figs. 5 and 6). This condition is most commonly seen in rectosigmoid endometriosis, with characteristic sonographic features classically reported in endocavity ultrasound as the “mushroom cap sign”, “pyramid sign”, “comet sign” and “moose antler sign”.3,8 The mushroom cap sign, also reported in MRI, consists of the convergence of the fibrotic implant in the serosa, with protrusion towards the submucosa/mucosa, adopting an intraluminal endophytic growth pattern (Figs. 1, 7 and 8).16 The pyramid sign denotes that the base of the implant is attached to the intestinal wall with the vertex pointing towards the uterus or mesenteric fat (Fig. 5). The comet sign refers to the implant having a fusiform shape, with tapering at both ends of the thickened area (Figs. 38 and Fig. 99).17 Other lesions have spikes or bands that extend from the centre of the implant and resemble a moose antler (Fig. 10).3,8 Some lesions have a tubular or plaque appearance, with more or less irregular margins (Fig. 3). In some cases, ultrasound detects the focus of endometriosis as a cause of low-grade obstructive conditions (Figs. 2 and 11). On rare occasions, it may be seen as a cystic mass or with mixed content. There are very few publications on the behaviour of endometriosis lesions following injection of contrast.4,10 Enhancement can be either homogeneous or heterogeneous, depending on whether the predominant component is fibrosis or bleeding (Fig. 12). In our experience, the image detected by abdominal ultrasound has a high degree of correlation with MRI; this is consistent with the scientific literature.18

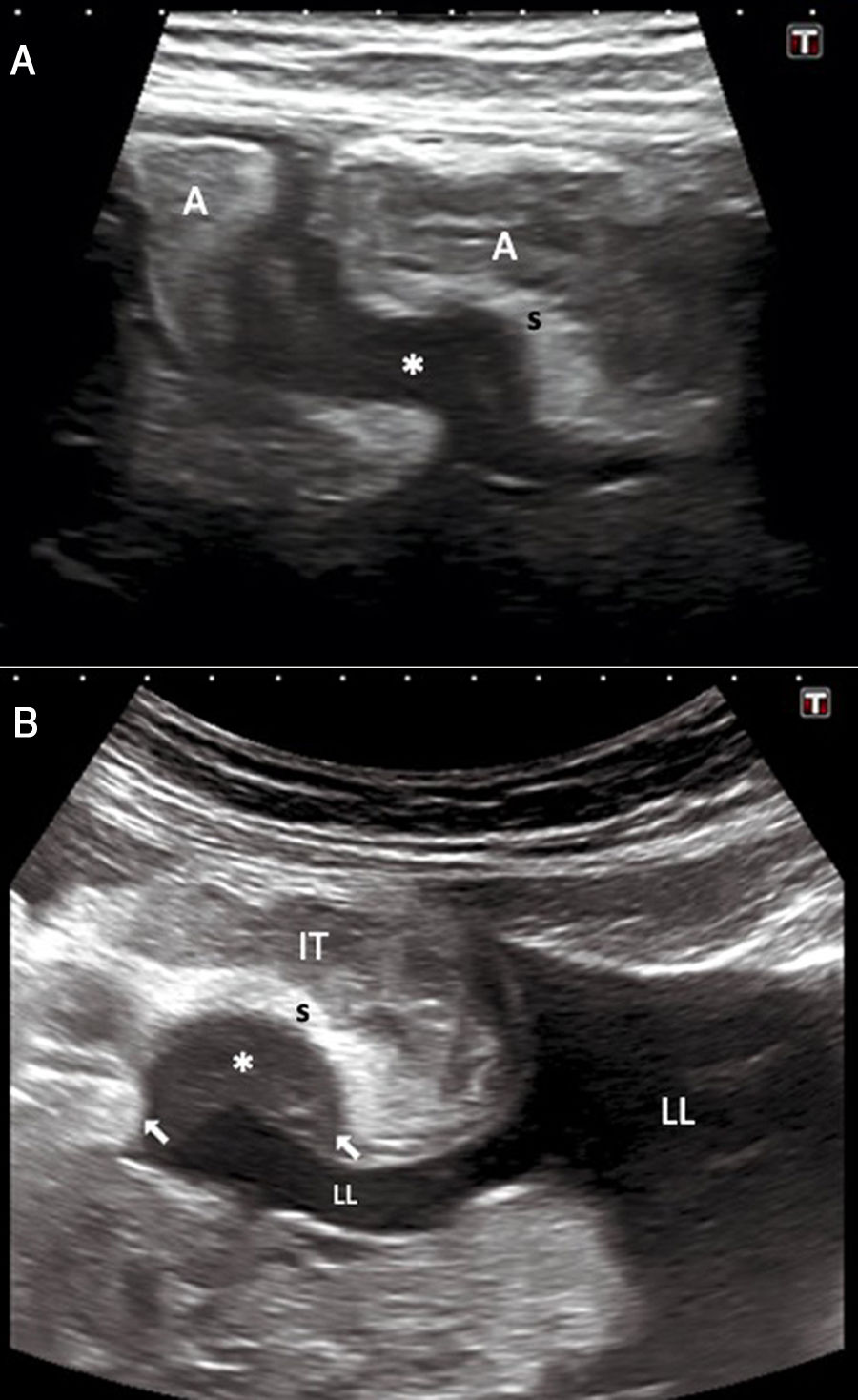

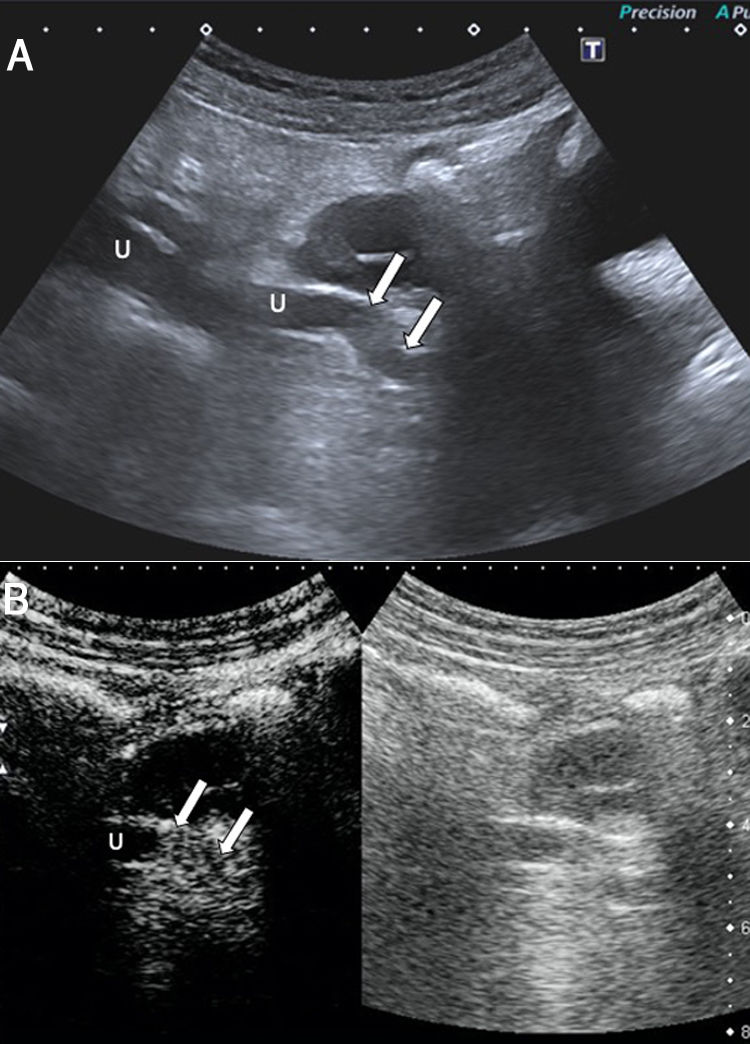

A 37-year-old woman with abdominal pain, a history of Caesarean section and Crohn’s disease, with no clinical or laboratory criteria for activity. A and B) Abdominal ultrasound identifies the terminal ileum (IT) with its slightly thickened wall and two hypoechoic lesions (**) attached to the serosal surface, suggestive of endometrial implants. The first ultrasound image has a plaque morphology, while the second has a nodular morphology. U: uterus; S: sigmoid colon.

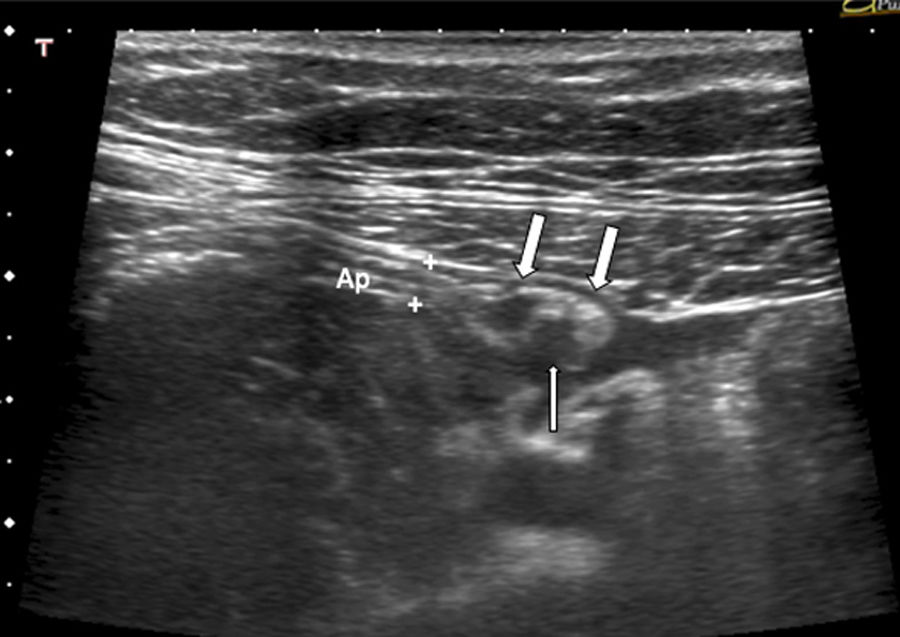

A 38-year-old woman with right iliac fossa pain and suspected acute appendicitis. Longitudinal plane of the normal appendix showing slight thickening at the tip (arrows) with a small hypoechoic mass adhered to the serosa (thin arrow), suggestive of endometrial implant. The study of the specimen showed a focus of endometriosis of the appendix. Ap: appendix.

A 40-year-old woman with diffuse hypogastric pain and a history of endometriosis. A) Abdominal ultrasound identifies a hypoechoic lesion (*) adhered to the wall of two loops of small intestine and causing retraction of said loops. B) Another lesion identified in the sigmoid colon with similar morphological characteristics (*) and preserved wall echotexture. Both lesions have a pyramid shape, with the base adhered to the bowel wall. A: intestinal loop.

A 51-year-old woman with episodic hypogastric pain, nausea and vomiting. A) Abdominal ultrasound shows a hypoechoic lesion with a laminar morphology (*) adhered to two ileum loops (A), leading to retraction and stricture. B) The implant adhered to the terminal ileum (IT) is seen to have a nodular morphology (arrows). LL: Free fluid in the pelvis; S: submucosa. Note the different echogenicity of the endometrial implants and the free fluid. Surgical and pathology findings confirmed the diagnosis of bowel obstruction secondary to intestinal endometriosis.

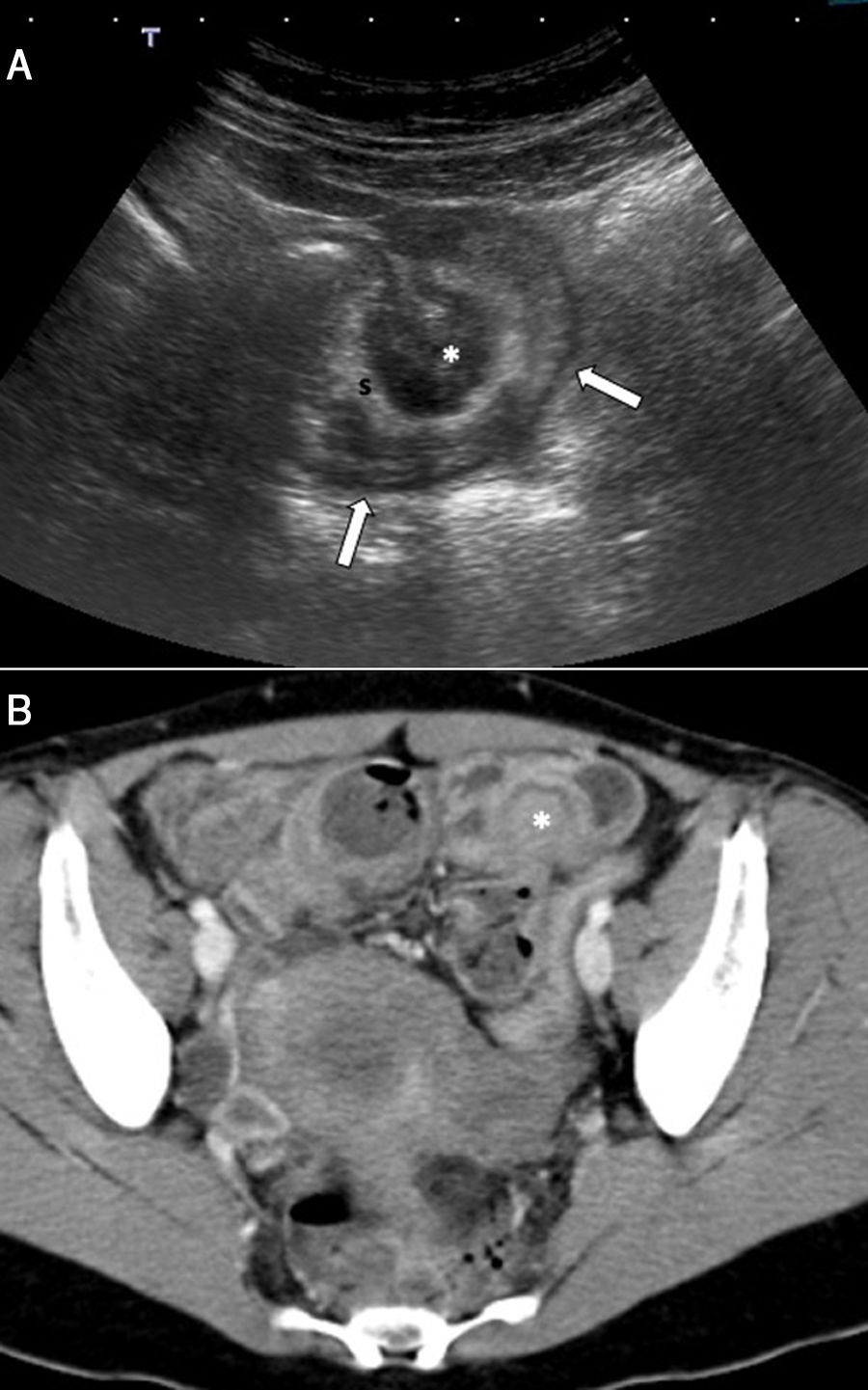

A 37-year-old woman with severe central abdominal pain, dysthymia, vomiting and constipation in the past few days. A) Abdominal ultrasound identifies a heterogeneous, mushroom cap-shaped hypoechoic lesion (*) adjacent to a loop of small intestine and pressing into the submucosal layer (S), leading to a decrease in the lumen of the affected loop (arrows). B) Computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast administration shows dilation of loops of small intestine secondary to the described eccentric nodular lesion (*). As this case shows, ultrasound enables better characterisation of these lesions compared to CT.

A 39-year-old woman with abdominal and low back pain along with fever. A) Abdominal ultrasound shows a hypoechoic nodular lesion (*) adjacent to the terminal ileum (IT). U: Uterus. B) Detail of the lesion with a high-frequency transducer enabling better identification of the layers of the bowel wall and the way in which the lesion is pressing into the submucosal layer and causing collapse of the intestinal lumen (arrows). Note the fusiform shape of the implant (“comet sign”) (thin arrows). The findings led to the diagnosis of endometrial implant. C) Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (T2-weighted sagittal TSE image) in which a hypointense lesion with a nodular morphology is observed in the sigmoid colon wall (arrow), corresponding to the lesion described in B. The pathology examination confirmed the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis.

A 44-year-old woman with diffuse abdominal pain for the past week and constipation, with a history of endometriosis. The ultrasound study showed findings suggestive of inflammatory/infectious colitis (not shown). Incidentally, there was evidence of a hypoechoic lesion in the ileum that was pressing into the submucosa (S) (image A, asterisk). Note the nodular morphology, the fusiform morphology ("comet sign") (narrow arrow) and the collapse of the lumen caused by the lesion (arrows). Another lesion with similar characteristics was identified in the terminal ileum (Image B, asterisk), with a nodular morphology. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (transverse T2-weighted TSE image) shows morphological findings similar to those reported by ultrasound (arrow). Pathology confirmed the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis. S: sigmoid colon, U: uterus, IT: terminal ileum.

A 28-year-old woman with severe abdominal pain coinciding with menstruation and associated nausea, vomiting and constipation. A) Abdominal ultrasound shows a hypoechoic lesion with lobulated borders (*) adjacent to the terminal ileum, which, in the patient's clinical context, suggests endometrial implant causing an obstructive condition. B) Transvaginal ultrasound. The presence of a hypoechoic lesion with spiculated margins adjacent to intestinal loops is confirmed, highly suggestive of endometrial implant (*), with dilation of loops and associated free fluid. C) Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (transverse T2-weighted TSE image) shows a lesion with intermediate signal intensity and spiculated margins (arrows) causing obstruction in the adjacent intestinal loops. Note that both the abdominal and the transvaginal ultrasound studies enable assessment of morphology similar to MRI. A: intestinal loops. U: Uterus. IT: terminal ileum.

A 36-year-old woman with poorly defined abdominal pain for 3 months, weight loss and repeated episodes of constipation. Ultrasound shows a hypoechoic nodular lesion suggestive of endometrial implant (*) causing dilation of proximal loops of small intestine. The loops of small intestine distal to the lesion are of normal calibre (arrows). Surgical and pathology findings confirmed the diagnosis of endometriosis. E: endometrial implant, ASA PRE: loop pre-stricture, ASA POST: loop post-stricture.

A 50-year-old woman with abdominal pain for the past 3 days. A) Abdominal ultrasound identifies a lesion with heterogeneous echogenicity, predominantly hypoechoic (*), involving the outer layers of the anterior wall of the descending colon, with the structure of the internal layers preserved. B) Following administration of ultrasound contrast (Sonovue®), the lesion (arrows) is delimited, and peripheral areas of enhancement (black asterisks) and an avascular centre (white asterisk) are identified. Although a gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) was initially suspected, the pathology examination detected an indurated nodule with areas of fibrosis and cystic lesions with haemorrhagic content of endometrial appearance. CD: descending colon.

Remember that: intestinal endometriosis is the most common form of extragenital infiltrating endometriosis and can be detected on abdominal ultrasound as hypoechoic lesions penetrating the muscularis propria.

The main differential diagnoses for these ultrasound features may include benign or malignant neoplasia of the colon, implants due to peritoneal carcinomatosis and diverticular disease.19 The characteristics which may aid in distinguishing endometriosis from malignant neoplasms are: a) normally, colon cancer is uncommon in people under 40 years of age; b) a clinical history of haematochezia is uncommon in endometriosis;19c) large endometriosis nodules have a significant fibrosis component which leads to retraction and stricture of the lumen (often in a C-shape with the convex part towards the lumen), while a malignant lesion causes stricture of the lumen due to endoluminal growth (Fig. 13);20 and d) the two conditions have clearly distinct sonographic appearances, as endometriosis originates in the serosa and invades the bowel wall from the outside, preserving the layered structure of the bowel wall, while colorectal cancer begins in the mucosal layer and penetrates through the muscle layers, thus destroying the layers of the wall.20 Laminated endometrial foci can simulate metastatic peritoneal implants, but this is usually seen in other clinical contexts.

A 30-year-old woman with episodes of dysuria coinciding with menstruation for some months. A) Transvaginal ultrasound, longitudinal plane. A lesion is identified with heterogeneous, predominantly hypoechoic, echogenicity, with lobulated borders (asterisk, arrows) in the posterosuperior wall of the bladder. B) Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (sagittal T2-weighted TSE image). The presence of a lesion in the posterosuperior wall of the bladder (arrows) is confirmed, with hyperintense foci within suggestive of glandular tissue and raising strong suspicion of endometrial implant. Note how this lesion causes some traction of the fundus of the uterus, increasing its anteflexion. Pathology confirmed the diagnosis of endometriosis. V: bladder. U: uterus.

In the ultrasound examination, the clinician should look carefully for other bowel lesions, as in more than 50% of cases there are associated lesions in another segment of the bowel (Figs. 3 and 7).

Remember that: in intestinal endometriosis the layered structure of the intestinal wall is maintained, while in colon cancer it is destroyed.

Infiltrating endometriosis of the urinary tract affects the bladder (15%) and the ureters (4.5%) in women with severe endometriosis.3 Ureteral involvement causes stricture of the lumen and obstructive uropathy with gradual loss of renal function. Unfortunately, diagnosis tends to be late and 47% of patients with ureteral endometriosis require nephrectomy as a result of the kidney damage caused.3

Ultrasound is the initial imaging method of choice for diagnosing urinary tract endometriosis. The transvaginal approach enables more precise evaluation of lesion size and muscle infiltration. Lesions tend to be elongated or spherical and hypoechoic or isoechoic to the bladder wall, with small anechoic spaces inside, described as “bubbles” (Fig. 13)3. In general, they are located in the posterior bladder wall and cause extrinsic compression of the bladder.3 Abdominal ultrasound can also be used to examine bladder lesions and assess the ureters (lesions, sites of dilation and sites of obstruction) and kidneys (hydronephrosis grading).4,9 Ureteral endometriosis is visualised as heterogeneous hypoechoic nodules which can resemble cancer (Fig. 14).3

A 46-year-old woman with pain in the right iliac fossa for 24h, with a previous episode of endometriosis requiring surgery (total hysterectomy, adnexectomy and left nephrectomy). A) Abdominal ultrasound shows ureteral dilation secondary to the presence of a lesion with intermediate echogenicity causing stricture of the distal third of the ureter (arrows). U: ureter. B) Following administration of ultrasound contrast (Sonovue®), the lesion is seen to enhance; this confirms that it is solid and suggests a differential diagnosis between endometrial implant and urothelial cancer. Pathology confirmed the diagnosis of endometrial implant. U: right ureter.

Remember that: abdominal ultrasound is the diagnostic tool of choice in the diagnosis of obstructive uropathy.

Associated findingsExtragenital infiltrating endometriosis often co-occurs with genital involvement. The abdominal approach allows the clinician to examine the ovaries for findings suggestive of endometriosis, such as medialisation of the ovaries due to adhesions (“kissing ovaries sign”) or the presence of adnexal masses of heterogeneous content, with no Doppler flow in their interior — findings corresponding to endometriomas (Fig. 15).2–9

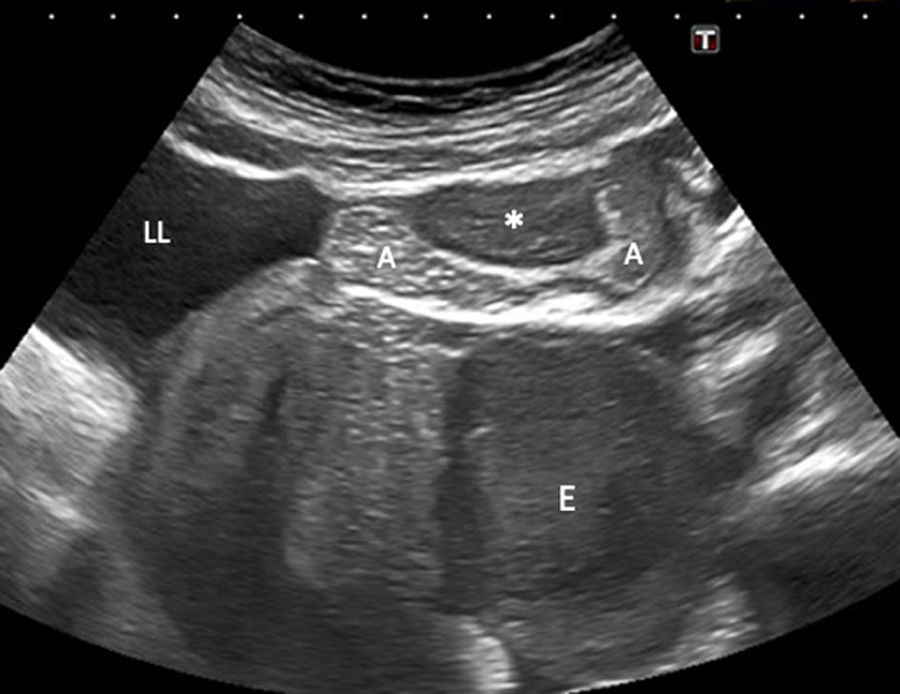

A 44-year-old woman with vomiting, bloating and abdominal pain, but no bowel rhythm abnormalities or fever. Abdominal ultrasound (longitudinal plane) shows a hypoechoic lesion involving the left adnexa suggestive of endometrioma (E), as well as a nodular lesion (*) involving the outermost layers of a loop of ileum leading to stricture of the lumen. Free fluid is also seen. The initial suspected diagnosis was endometriosis with intestinal involvement, and this was confirmed by pathology. E: endometrioma. A: intestinal loop. LL: free fluid.

In summary, non-invasive diagnosis of infiltrating endometriosis is typically performed by transvaginal ultrasound and MRI. The former should be used as an initial method, while the latter is reserved for preoperative planning. Sometimes, as the clinical signs and symptoms of infiltrating endometriosis are nonspecific, abdominal ultrasound may be the first-line diagnostic test. Findings suggestive of endometriosis classically reported with transvaginal ultrasound and MRI can be identified with abdominal ultrasound, as the image is quite characteristic, with high correlation demonstrated between these techniques (Figs. 1–4, 9, 10 and 13).

Knowledge of this disease and familiarity with its different ultrasound features helps radiologists to suggest the diagnosis and include it in the differential diagnosis of the multiple causes of pelvic pain in women of childbearing potential.

AuthorshipResponsible for study integrity: JSG, ELM, TRG, MJMP.

Manuscript conception: JSG, ELM, TRG, MJMP.

Manuscript design: JSG, ELM, TRG, MJMP.

Data acquisition: JSG, ELM, TRG, MJMP, JVDR.

Data analysis and interpretation: JSG, ELM, TRG, MJMP, JVDR.

Statistical processing: N/A.

Literature search: N/A.

Drafting of the manuscript: JSG, ELM, TRG, MJMP.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: JSG, ELM, TRG, MJMP.

Approval of the final version: JSG, ELM, TRG, MJMP.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García JS, Lorente Martínez E, Ripollés González T, Martínez Pérez MJ, Vizuete del Río J. Endometriosis infiltrante: claves diagnósticas en ecografía abdominal. Radiología. 2021;63:32–41.

![A 27-year-old woman with hypogastric pain not improving with usual analgesia. A) Abdominal ultrasound shows a hypoechoic nodule (*) attached to the wall of the sigmoid colon which is penetrating into the muscularis propria with growth towards the submucosa (S), causing the lumen to collapse (arrows). B) The study using pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (transverse T2-weighted turbo spin echo [TSE] image) confirms a lesion with a nodular morphology (*) in the sigmoid colon wall, with growth towards the submucosa and hyperintense foci inside suggestive of glandular tissue. The patient required surgery and the pathology confirmed intestinal endometriosis. A 27-year-old woman with hypogastric pain not improving with usual analgesia. A) Abdominal ultrasound shows a hypoechoic nodule (*) attached to the wall of the sigmoid colon which is penetrating into the muscularis propria with growth towards the submucosa (S), causing the lumen to collapse (arrows). B) The study using pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (transverse T2-weighted turbo spin echo [TSE] image) confirms a lesion with a nodular morphology (*) in the sigmoid colon wall, with growth towards the submucosa and hyperintense foci inside suggestive of glandular tissue. The patient required surgery and the pathology confirmed intestinal endometriosis.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/21735107/0000006300000001/v1_202101300735/S2173510720301154/v1_202101300735/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)