To analyse the imaging characteristics of histologically diagnosed metastases to the breast.

Material and methodsWe selected patients histologically diagnosed with metastases to the breast in our diagnostic and interventional breast imaging unit between March 2010 and September 2018.

ResultsA total of 9 patients (all women; mean age, 60 y; age range, 28–89 y) were diagnosed with metastases to the breast. In 1 (11.11%) case, the primary disease was diagnosed from the breast lesion. The primary tumours were melanoma (n=5), neuroendocrine tumour (n=2, one from the small bowel and one from the cervix), lung adenocarcinoma (n=1), and ovarian cancer (n=1). The clinical and imaging manifestations depend on the type of dissemination of disease and can simulate benign and malignant primary breast lesions.

ConclusionThere is no specific imaging pattern for metastases to the breast that would help to orient the diagnosis. It is important to consider this etiological possibility if the patient has a history of a primary tumour in another organ.

El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar las características radiológicas de lesiones con diagnóstico histológico de metástasis en la mama.

Material y métodosEn la Sección de Diagnóstico e Intervencionismo mamario, en el período comprendido entre marzo de 2010 y septiembre de 2018 se seleccionaron 9 pacientes que presentaban diagnóstico anatomopatológico de metástasis en la mama.

ResultadoEn total se registraron 9 pacientes de sexo femenino con diagnóstico de metástasis en la mama. La media de edad fue de 60 años (rango: 28-89 años). En 1 caso (11,11%), el diagnóstico de la enfermedad primaria se realizó a partir de la lesión mamaria. Se diagnosticaron cinco metástasis de melanoma, dos metástasis de carcinomas neuroendocrinos (uno de origen en intestino delgado y otro de origen en cérvix uterino), una metástasis de adenocarcinoma de pulmón y una metástasis de ovario. Las manifestaciones clínicas y de imagen dependen de la forma de diseminación de la enfermedad y pueden simular lesiones benignas y malignas primarias de la mama.

ConclusiónLas metástasis en la mama no presentan un patrón imagenológico específico que nos oriente a este diagnóstico. Es importante pensar en esta posibilidad etiológica si el paciente presenta el antecedente del diagnóstico de un tumor primario en otro órgano.

Metastases in the breast of extramammary origin are an extremely rare entity. The published rates range between 0.5 and 2% of all breast neoplasms. They are usually diagnosed in the context of advanced disease with systemic involvement and/or a history of some type of known cancer,1 but they can be the first manifestation of the primary tumour in up to 30% of cases.2,3

Melanoma is the most common primary tumour that metastasises in the breast. Other neoplasms, such as those of pulmonary, gastrointestinal, gynaecological, head and neck and genitourinary origin, are less frequent.1

The lesions are usually multiple and/or bilateral, typically have a non-specific appearance in imaging and can be confused with primary benign or malignant processes of the breast.3

The objective of this paper is to analyse the imaging and clinical characteristics of histologically diagnosed metastases in the breast.

Material and methodsThis was a retrospective study, approved by our hospital's ethics committee, focused on the descriptive analysis of histologically diagnosed metastases in the breast.

We selected nine patients anatomopathologically diagnosed with metastases in the breast in our diagnostic and interventional breast imaging unit between March 2010 and September 2018. The clinical histories and images of the patients were reviewed.

The patients were examined using a Fuji digital mammography unit. As part of the diagnostic process, ultrasounds were performed with Esaote My Lab equipment with a 12MHz linear probe and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with a dedicated 1.5T Avanto breast coil, Siemens; the acquisition of images included T1- and T2-weighted sequences, diffusion and dynamic study after gadolinium administration, and ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy with a 14G Tru-Cut needle.

The acquired and anonymised images were part of a database that was reviewed by three imaging specialists dedicated exclusively to the breast (professional experience of between 5 and 18 years). Age, clinical picture, type of primary tumour, synchronicity of the diagnosis, number and type of lesions and survival time were recorded. The variables of size (longitudinal maximal diameter), margins, internal characteristics of the mass (solid homogeneous or heterogeneous, calcification), vascularisation in the ultrasound and behaviour with contrast in the MRI were evaluated.

ResultsA total of nine female patients with a diagnosis of metastases in the breast were recorded. The mean age was 61 years (range: 28–89 years).

In one case, the primary disease was diagnosed from the breast lesion. In eight cases, the secondary disease was diagnosed between the first and third year of the diagnosis of the primary tumour.

In five (55.6%) patients the breast lesion was diagnosed because they consulted for a palpable breast nodule and in four (44.4%) patients it was due to a finding in the images.

The size of the nodular lesions in the breast ranged between 0.7 and 10cm.

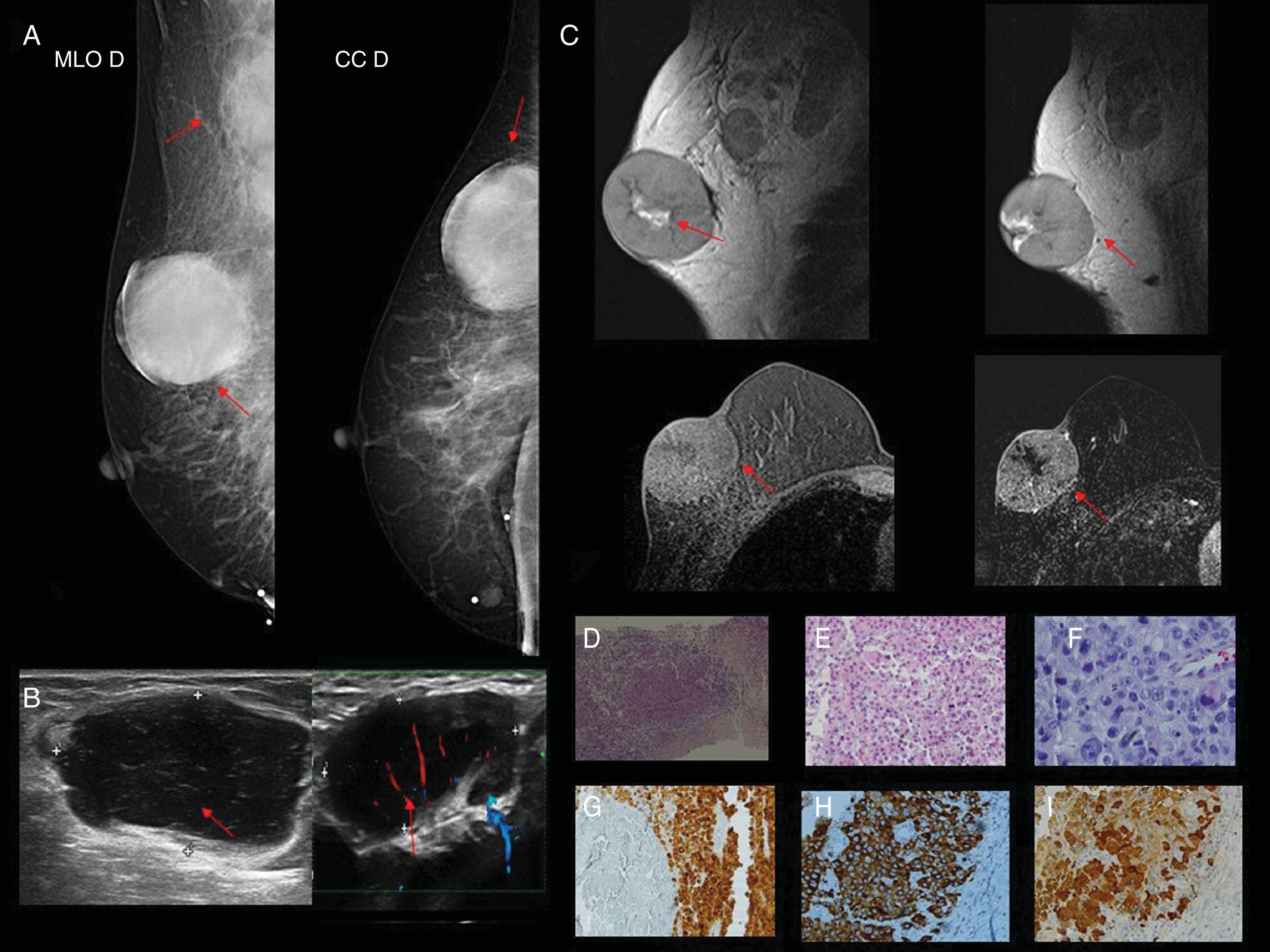

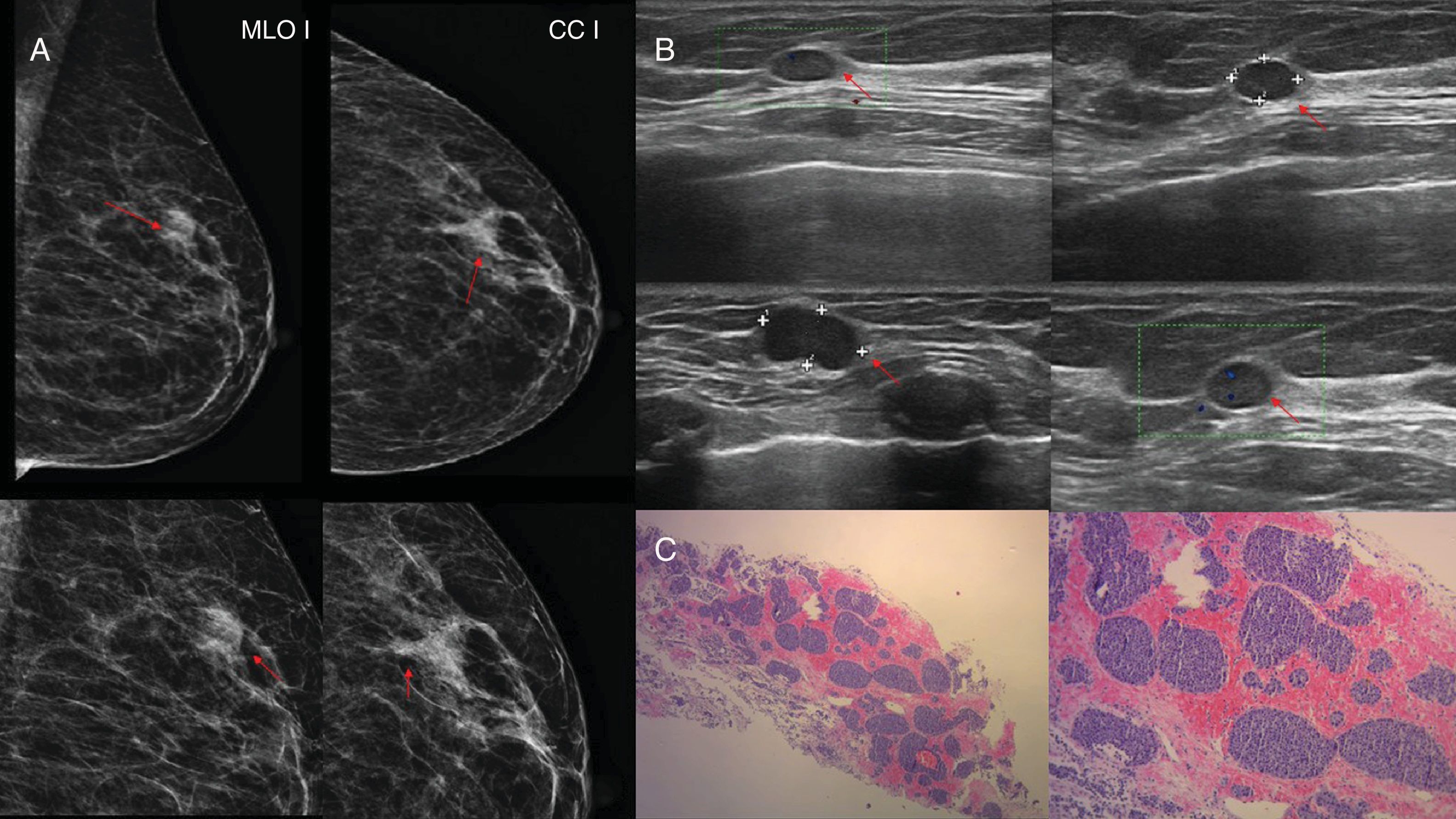

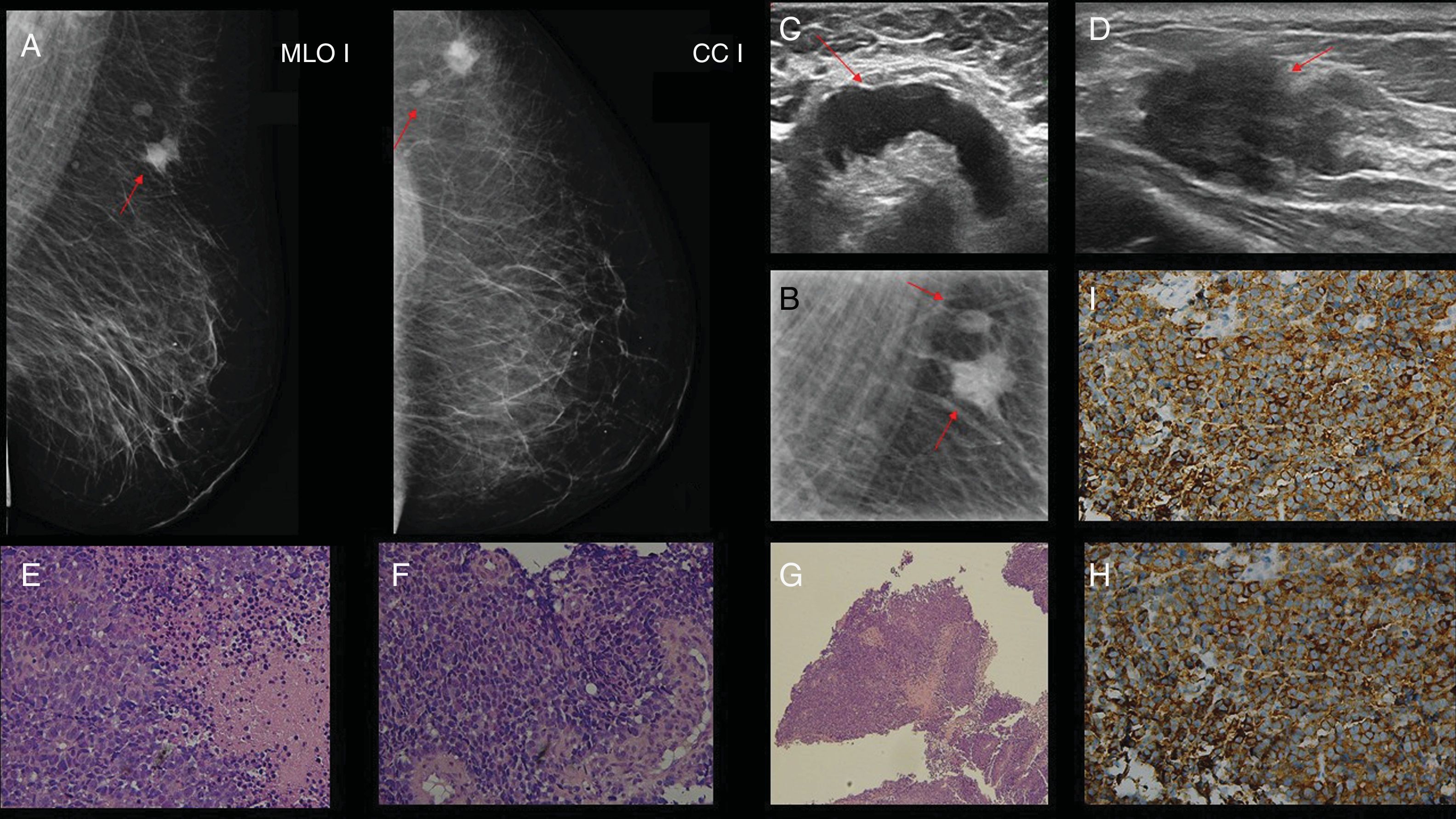

Five metastatic melanomas (Fig. 1), two metastatic neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) [one of the small intestine (Fig. 2) and another of the small cell of the uterine cervix Fig. 3, an adenocarcinoma of the lung (Fig. 4) and a metastasis in the ovary, (Fig. 5) were diagnosed. These were single lesions in seven out of nine (77.7%) of our cases.

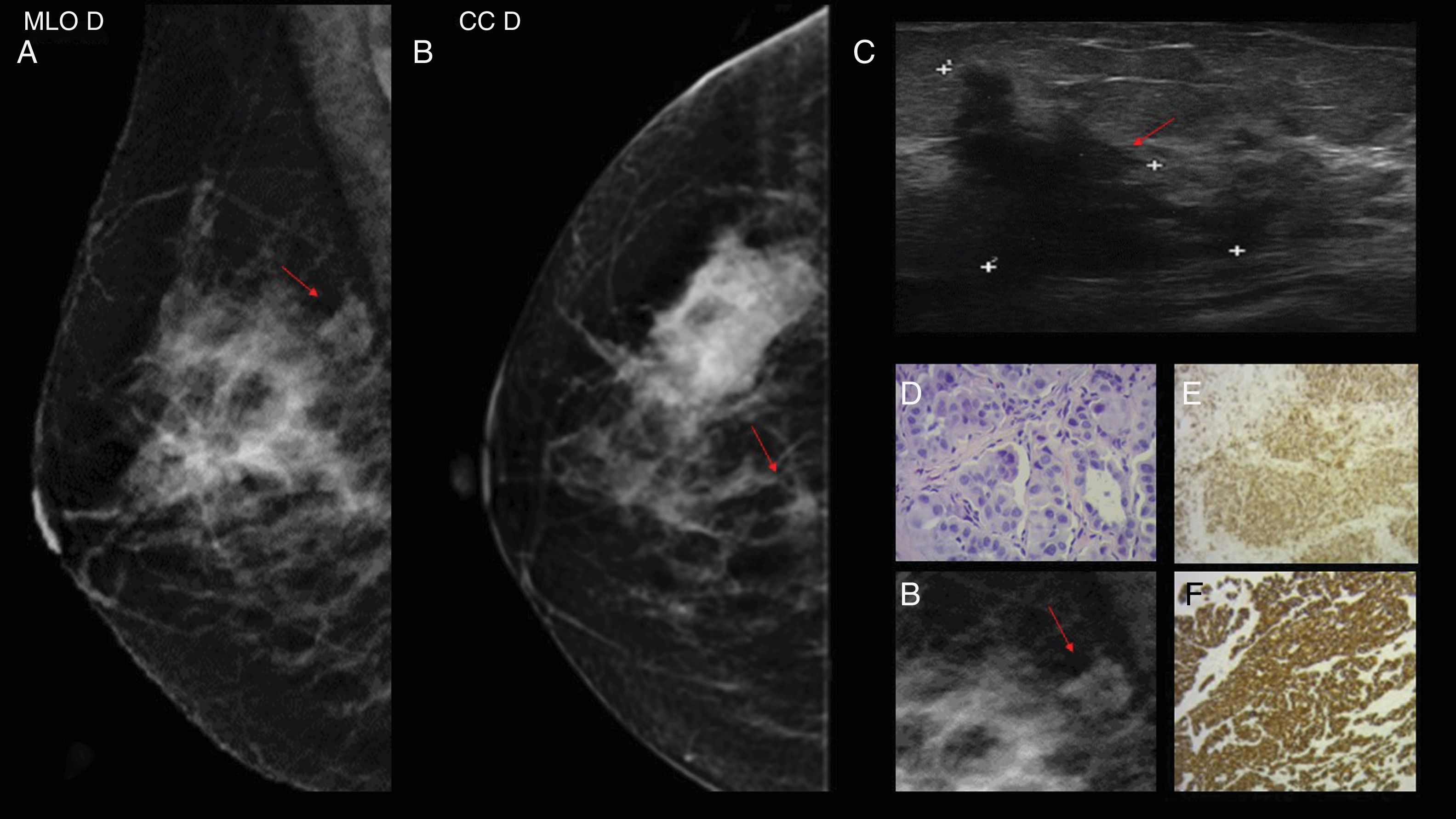

Case 2. 81-year-old patient with a history of melanoma diagnosis two years prior. (A) Mammography in the craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique incidence of the right breast (RB). In the upper outer quadrant (UOQ) a circumscribed, hyperdense nodule (red arrow) is visualised; in right axillary extension, lymph node enlargement (red arrow). (B) Ultrasound of solid, hypoechoic nodule with circumscribed margins in the UOQ of RB (red arrow); in the homolateral axilla, lymph nodes with loss of the cortex-hilum area ratio (red arrow). (C) MRI in which a nodular image with a high-intensity signal is observed in the UOQ of the RB in the T1 and T2 sequences without contrast, with heterogeneous enhancement with the intravenous contrast and a central hypointense area of possible necrosis (red arrow). Right lymph node enlargement with tortuous vascularisation with Doppler (red arrow). (D) Haematoxylin–eosin (H&E) 2.5×: the histological sections show mammary parenchyma replaced by a neoplastic proliferation that grows in fields in a discohesive pattern with the presence of tumour necrosis. (E and F) H&E 4× and 10×: atypical cells with marked pleomorphism and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm are observed. Obvious nucleolus and intranuclear vacuoles can be recognised. (G and H) Immunohistochemistry with melanin markers (Melan A, HMB 45 and S100) being their positive markers.

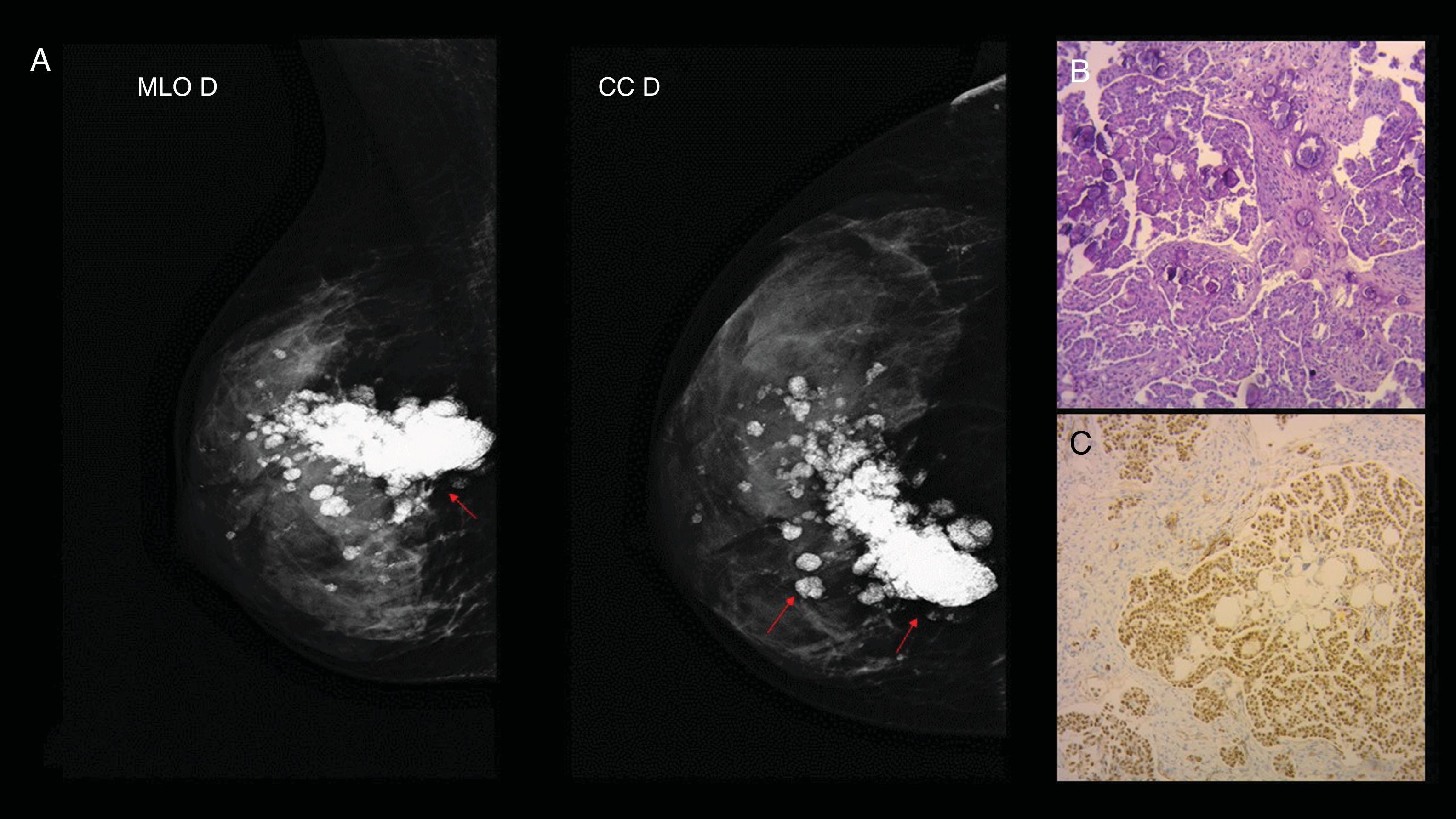

Case 5. 74-year-old woman diagnosed one year prior with neuroendocrine tumour of the intestine. (A) Left breast mammography with mediolateral oblique and craniocaudal incidence and incidence magnified in the upper outer quadrant (UOQ) where a dense, oval nodule with microlobulated margins is observed (red arrow). (B) Left breast ultrasound of the UOQ where a hypoechoic, oval nodule is observed, solid, with microlobulated margins, with positive Doppler (red arrow). (C) Anatomical pathology (haematoxylin–eosin 2.5× and 10×): neuroendocrine tumour with a glandular pattern in “nests” and with nuclear hyperchromatism; manifests typical round or oval nuclei with irregular stippled nucleoli. Immunohistochemistry: positive chromogranin.

Case 6. 50-year-old woman with a diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumour of the cervix two years prior. (A and B) Unilateral mammography of the left breast with mediolateral oblique incidence, craniocaudal incidence and magnified incidence; a dense, oval, nodular image with indistinct margins (red arrow), adjacent to the same lymph node image with increased density at the cortical level (red arrow) is visualised in the upper outer quadrant. (C and D) Ultrasound of intramammary lymphadenopathy with thickening of the cortex and tortuous vascularisation with Doppler in the cortex and solid, hyperechoic, oval nodular image with indistinct margins (red arrow). (E–G) Haematoxylin–eosin (H&E 2.5× and 10×): the histological sections show neoplastic proliferation of atypical epithelial cells, of hyperchromatic nuclei with anisokaryosis and obvious nucleolus that are arranged on solid fields with nuclear moulding. Mitosis and the presence of tumour necrosis common. (H and I) Immunohistochemistry with positive neuroendocrine (chromogranin and synaptophysin) markers.

Case 4. 68-year-old woman with diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the lung 14 months prior. (A and B) Mammography in craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique projection in which an irregular, dense, nodular image with indistinct margins is observed in hour 12, posterior plane of right breast (red arrow) categorised as BI-RADS 4C, better visualised in the magnified incidence (B). (C) Mammary ultrasound showing a hypoechoic, nodular image with a solid, irregular appearance (red arrow), with indistinct margins in the upper outer quadrant (hour 9) of the right breast (palpable) of approximately 3×2cm. BI-RDS 4C. (D) Haematoxylin–eosin (40×): the sections show neoplastic infiltration of atypical epithelial cells of hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm that are arranged forming glands and nests and infiltrate a desmoplastic stroma. E and F) The sections show positive neoplastic proliferation for CK7 and napsin by immunohistochemistry (Benchmark XT).

Case 7. 28-year-old woman with diagnosis of papillary serous ovarian carcinoma one year prior, who consulted for palpable, hard, stony nodule in the right breast. (A) Mammography of the right breast: mediolateral oblique and craniocaudal incidence where images compatible with psammoma bodies are visualised (red arrows). (B) Anatomical pathology: papillary serous carcinoma. Haematoxylin–eosin (H&E 10×): the histological sections show neoplastic infiltration of atypical epithelial cells of hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm that are arranged in a papillary and cribriform architecture. Presence of numerous psammoma bodies. (C) H&E 10×: positive labelling for WT1 with immunohistochemical techniques (Benchmark XT). This positive labelling is found within a panel of antibodies (CK7, positive oestrogen receptor and negative labelling for GATA3 and GCDFP 15).

All the patients died between the first and the fifth year following the diagnosis of secondary disease in the breast.

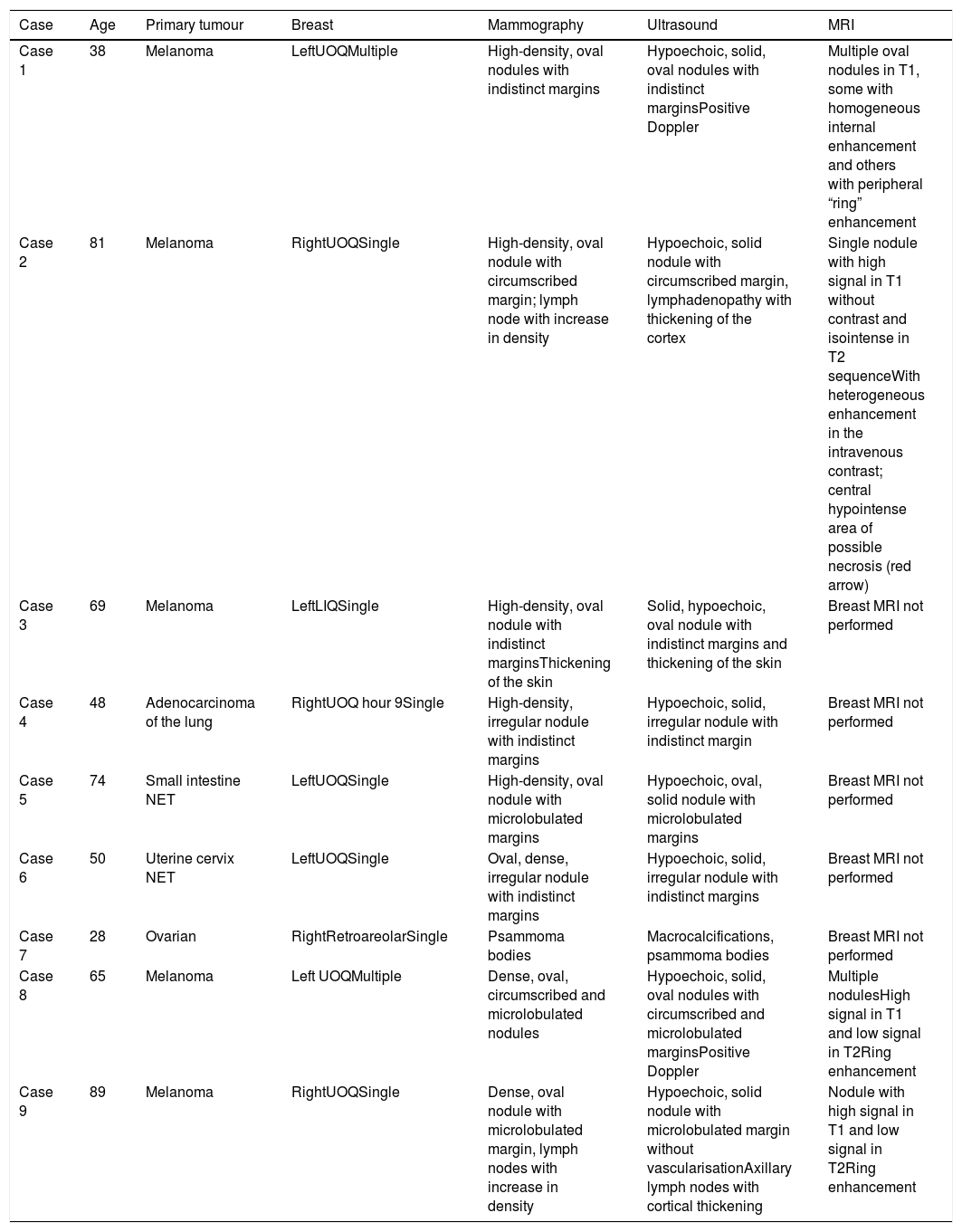

The most common characteristics from the mammographic images were high density nodules, with microlobulated or indistinct margins without desmoplastic reaction, and calcifications were exceptional (Table 1).

Characteristics of the mammography images.

| Case | Age | Primary tumour | Breast | Mammography | Ultrasound | MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 38 | Melanoma | LeftUOQMultiple | High-density, oval nodules with indistinct margins | Hypoechoic, solid, oval nodules with indistinct marginsPositive Doppler | Multiple oval nodules in T1, some with homogeneous internal enhancement and others with peripheral “ring” enhancement |

| Case 2 | 81 | Melanoma | RightUOQSingle | High-density, oval nodule with circumscribed margin; lymph node with increase in density | Hypoechoic, solid nodule with circumscribed margin, lymphadenopathy with thickening of the cortex | Single nodule with high signal in T1 without contrast and isointense in T2 sequenceWith heterogeneous enhancement in the intravenous contrast; central hypointense area of possible necrosis (red arrow) |

| Case 3 | 69 | Melanoma | LeftLIQSingle | High-density, oval nodule with indistinct marginsThickening of the skin | Solid, hypoechoic, oval nodule with indistinct margins and thickening of the skin | Breast MRI not performed |

| Case 4 | 48 | Adenocarcinoma of the lung | RightUOQ hour 9Single | High-density, irregular nodule with indistinct margins | Hypoechoic, solid, irregular nodule with indistinct margin | Breast MRI not performed |

| Case 5 | 74 | Small intestine NET | LeftUOQSingle | High-density, oval nodule with microlobulated margins | Hypoechoic, oval, solid nodule with microlobulated margins | Breast MRI not performed |

| Case 6 | 50 | Uterine cervix NET | LeftUOQSingle | Oval, dense, irregular nodule with indistinct margins | Hypoechoic, solid, irregular nodule with indistinct margins | Breast MRI not performed |

| Case 7 | 28 | Ovarian | RightRetroareolarSingle | Psammoma bodies | Macrocalcifications, psammoma bodies | Breast MRI not performed |

| Case 8 | 65 | Melanoma | Left UOQMultiple | Dense, oval, circumscribed and microlobulated nodules | Hypoechoic, solid, oval nodules with circumscribed and microlobulated marginsPositive Doppler | Multiple nodulesHigh signal in T1 and low signal in T2Ring enhancement |

| Case 9 | 89 | Melanoma | RightUOQSingle | Dense, oval nodule with microlobulated margin, lymph nodes with increase in density | Hypoechoic, solid nodule with microlobulated margin without vascularisationAxillary lymph nodes with cortical thickening | Nodule with high signal in T1 and low signal in T2Ring enhancement |

UOQ: upper outer quadrant; NET: neuroendocrine tumour.

On the ultrasound they manifested as oval nodules, with circumscribed (22.2%), indistinct (44.4%) or microlobulated (33.3%) margins. Our results differ from those published by other groups with a greater number of case studies, where the most common appearance is that of circumscribed margins. Our series is small enough to draw conclusions from the differences observed.

In those cases with lymphatic dissemination, thickening of the skin, oedema and swollen lymph nodes were observed. In MRI, as lesions in the form of round or oval masses with intermediate signal in T2-weighted sequences and low signal in T1-weighted sequences (except for melanoma metastases).

DiscussionIn order of frequency, the main tumours that produced metastases in the breast were: melanoma, sarcomas, lung tumours and ovarian carcinomas.1–7 In our series, melanoma was the most common primary tumour.

In patients with known malignant neoplasms, metastatic breast lesions are often incidentally identified in routine examinations performed for systemic staging or post-therapeutic follow-up, with computed tomography (CT) and PET-CT (positron emission tomography-computed tomography)5–9; in our series, incidentalomas occurred in 44.4%.

Of the lung metastases, the small cell subtype is the most frequent. However, in our series, the histological subtype found was the “non-small cells” variant. In the latter, metastases usually appear after diagnosis of the primary (metachronous) tumour, a finding observed in our patient.1–7

Regarding the NETs, these can come from multiple organs due to the wide distribution of these cells in the body; the most common are those of the digestive tract and lungs.8

The appearance of the metastatic lesion in the breast depends on the cancer dissemination routes, haematogenous or lymphatic. In general, the lesions disseminated via the haematogenous route are circumscribed and can mimic benign nodules or malignant primary tumours (mucinous or papillary carcinoma). In contrast, lymphatic dissemination can lead to diffuse involvement of the breast, oedema, trabecular thickening and thickening of the skin, which can mimic an inflammatory process such as mastitis or inflammatory carcinoma.1,7

The most common location for metastases, as in primary breast cancer, is in the upper outer quadrants, probably due to the increase in blood supply in this region, a fact that coincides with our series. In our case studies, all the metastases were unilateral: five in the left breast and four in the right breast.

Appearance in the form of a single nodular lesion and with circumscribed margins can lead to incorrect interpretation and be confused with primary tumours of the breast or benign lesions.

Single lesions occurred in seven out of nine (77.7%) of our cases. This data reaffirms the need to always perform percutaneous histological diagnosis of the lesion for all patients. If extramammary origin is confirmed, unnecessary surgical procedures to the breast will be avoided.

The most common image in mammography is that of a dense or isodense nodule, without the spiculated margins or signs of adjacent desmoplastic reaction that characterise the majority of primary breast carcinomas. In some cases they may show microlobulated or indistinct margins. Calcifications are rare and occur more frequently in patients with ovarian cancer due to the presence of psammoma bodies.1–7

On the ultrasound they appear as round or oval, solid, hypoechoic nodules, with circumscribed, indistinct or microlobulated margins.3,4 These lesions are most commonly located superficially in the subcutaneous tissue or immediately adjacent to the breast parenchyma, a topography that is relatively rich in blood supply.

Although most lesions are hypoechoic, the echostructure may be heterogeneous and show anechoic or hyperechoic areas, often associated with posterior acoustic enhancement.

Doppler can be useful, mainly in differential diagnosis with benign lesions, such as fibroadenomas and cysts.3,4

Sippo et al. describe a series of patients in whom these lesions appear with a mammographic pattern of high density, single or multiple, and in ultrasonography, as hypoechoic, oval, circumscribed or microlobulated masses, with positive Doppler.5 These findings coincide with ours.

Surov et al. describe melanoma metastases that are hypervascular with Doppler, and in MRI, hyperintense in T1 due to melanin, and in some cases due to areas of bleeding, which are frequent in this type of pathology.8 In our series, the lesions were observed as multiple, hypoechoic, solid nodules with microlobulated and indistinct margins with positive Doppler. In one of the cases, MRI showed hyperintense lesions in T1 with ring enhancement after intravenous contrast administration.

Another variable that must be taken into account is the marked involvement of axillary lymph nodes by melanoma, especially if the primary lesion is located in the upper limb, as was observed in two of our patients with a primary tumour located in the shoulder.4

In MRI, most metastatic lesions show an intermediate signal in the T2 sequence, and a low signal in the T1 sequence, with the exception of melanoma metastases, which can show a high signal in the T1-weighted images and a low T2 signal indicating that the tumour contains melanin. In our case studies, one of the cases differed from the more characteristic appearance of melanoma, since it was isointense in T2.

After the administration of paramagnetic contrast, an intense, rapid and homogeneous uptake is usually observed, with a plateau without washout in the delayed phase of the kinetic curve.

It is not possible to differentiate metastatic lesions from primary carcinomas of the breast by PET-CT.5–10

When a patient has a suspicious nodule in the breast, investigating history of a previous extramammary neoplasm should not be overlooked, since this clinical detail can be a key element for guiding the diagnosis. The relevance of integrating the clinical picture, history, images and anatomical pathology in order to arrive at a correct diagnosis should be noted, since the prognosis and management of metastases in the breast differ from those of primary carcinoma of the breast.

Metastatic tumours usually manifest systemic involvement at onset, with an ominous survival rate in contrast to primary breast carcinoma. In our series, the average survival was 26 months, so it does not differ from the data provided by other series.

The multidisciplinary management of this pathology is crucial. The pathologist plays a fundamental role in the medical team and must have deep knowledge of the different markers to be used in the immunohistochemical panel.

Immunohistochemical panels can be of great value when it comes to distinguishing mammary carcinoma from mammary metastases, since the histopathological findings evaluated with haematoxylin–eosin often show overlapping images. Therefore being aware of their expression is a fundamental tool. There are different molecules expressed in tissue of mammary origin that help to distinguish primary from metastatic origin, such as GCDFP 15, GATA 3, mammaglobin and oestrogen and progesterone receptors.11

The GATA 3 marker has been shown to be the most sensitive antibody, with adequate specificity to confirm primary origin.12 However, no marker is totally specific. For example, the oestrogen receptor can be expressed in ovarian cancer, and GATA 3 is also a sensitive marker for urothelial cancer.13 These markers should always be used in a panel of antibodies, since no single marker is completely sensitive or specific.11

In melanoma, the melanin pigment can sometimes be visualised in some neoplastic cells, but amelanotic melanomas exist, so it is useful to confirm the diagnosis by means of immunohistochemistry. Positivity for MELAN A, S-100 and HMB-45 proteins confirm its diagnosis.

ConclusionThere is no specific imaging pattern for metastases in the breast that can help us to orient the diagnosis. Due to their imaging appearance they can be confused with primary breast tumours or in some cases with benign lesions.

It is important to consider this aetiological possibility if there is a primary tumour in another organ. Suspicion and confirmation of the diagnosis are fundamental for appropriate therapeutic planning, because management of patients is different to that for a primary breast tumour. These lesions have a grim prognosis.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: KP.

- 2.

Study conception: KP.

- 3.

Study design: KP.

- 4.

Data collection: KP, ACZS, JSD and AW.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: KP, MJC and CH.

- 6.

Statistical processing: N/A

- 7.

Literature search: KP, MJC, CH, ACZS, JSD and AW.

- 8.

Drafting of the paper: KP.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: KP and MJC.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: KP, MJC, CH, ACZS, JSD and AW.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pesce K, Chico MJ, Sanabria Delgado J, Zabala Sierra AC, Hadad C, Wernicke A. Metástasis en la mama, un diagnóstico infrecuente. ¿Qué deben saber los radiólogos? Radiología. 2019;61:324–332.