We aim to review the characteristics of Morel-Lavallée lesions and to evaluate their treatment.

Material and methodsWe retrospectively reviewed 17 patients (11 men and 6 women; mean age, 56.1 years, range 25–81 years) diagnosed with Morel-Lavallée lesions in two different departments. All patients underwent ultrasonography, 5 underwent computed tomography, and 9 underwent magnetic resonance imaging. Percutaneous treatment with fine-needle aspiration and/or drainage with a 6–8F catheter was performed in 13 patients. Two patients required percutaneous sclerosis with doxycycline.

ResultsAll patients responded adequately to percutaneous treatment, although it was necessary to repeat the procedure in 4 patients.

ConclusionsRadiologists need to be familiar with this lesion that can be treated percutaneously in the ultrasonography suite when it is not associated with other entities.

Revisar las características de las lesiones de Morel-Lavallée y valorar su tratamiento.

Material y métodosHemos revisado de forma retrospectiva 17 pacientes diagnosticados de lesión de Morel-Lavallée en dos servicios diferentes: 11 hombres y 6 mujeres, edad media 56,1 años, rango de edad 25-81 años. En todos se hizo un estudio con ecografía, en cinco se realizó tomografía computarizada y en nueve resonancia magnética. Trece fueron tratados de forma percutánea mediante aspiración con aguja fina o drenaje con catéter de 6-8 F, o con ambos procedimientos. Dos pacientes requirieron esclerosis percutánea con doxiciclina.

ResultadosTodos los pacientes respondieron de forma adecuada al tratamiento percutáneo, aunque en cuatro hubo que repetir el procedimiento.

ConclusionesEl radiólogo debe estar familiarizado con esta patología cuyo tratamiento percutáneo, cuando no está asociada a otras afecciones, puede realizarse con éxito en la sala de ecografía.

The Morel-Lavallée lesion (MLL) was described for the first time by a French surgeon back in the year 1863. The disease is named after him. This collection proximal to the greater trochanter is due to one tangential impact that causes shear between the hypodermis and the underlying muscle fascia, forming a cavity that fills up with blood or lymph, with presence of other fibrous remains. This fact determines its variable radiological presentation.1,2 Some additional findings can be inflammatory changes, and the formation of one pseudo-capsule that not only prevents the resolution of this collection, but also promotes its growth and chronicity.3–5

The name of MLL-type lesions is applied to similar collections located in the abdominal wall, scapular region, buttocks, calves, or suprapatellar region of the knees.6–8

The radiological findings are based on the chronology of the lesion. On the ultrasound we may find one hyperechogenic collection if the hematoma component is predominant, that may become progressively hypoechoic, and even anechoic.9 The computed tomography (CT) scan shows fluid attenuation too, and even fluid-fluid levels can be seen when the lesion is subacute or chronic. Similarly, on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), its appearance can be highly variable, which is why a MLLs have been categorized into five (5) different categories: type I is one homogeneous and hypointense seroma on T1, hyperintense on T2; type II is one subacute hematoma of hyperintense appearance, and one hypointense ring on all sequences that is representative of the pseudo-capsule; type III looks like one chronic organized hematoma; types IV (closed laceration) and V (pseudonodular image) are more rare.10,11

Although most of the time the diagnosis is easy to achieve due to the presence of traumatic history and one subcutaneous collection, at times, differential diagnosis is difficult to achieve, and it can be suggested with other soft tissue lesions.5,10–13

When it comes to management, there is not such a thing as one established standard treatment.14 In small lesions, conservative treatment is feasible by draining the collection and using compression bandage systems. In complex lesions, especially in the presence of pseudo-capsule formation, surgery is the most widely accepted treatment. Recently, the techniques of alcohol or doxycycline sclerotherapy have proven valid.15

Our goal is to review the radiological characteristics of the MLL, especially the ultrasound and the MRI, and describe our own experience with ultrasound-guided percutaneous treatment in the cases reported by our hospitals during the last 7 years.

MethodsWe retrospectively reviewed all cases with an ultrasound diagnosis of MLL achieved in the services of radiology of two different hospitals consecutively back in 2010. Patients with fractures or open lesions were not included. Given the retrospective nature of the study, it was not deemed necessary to have the authorization of the hospital ethical committees.

In total, the series included 17 patients with the aforementioned diagnosis: 11 men and 6 women, mean age 56.1 years old (range: 25–81 years). In 12 patients, there was a traumatic history, and 5 patients did not mention or could not remember it.

All patients underwent ultrasound procedures on their soft tissues, including Color Doppler ultrasounds. Nine (9) patients underwent an MRI (in two of them with the IV administration of gadolinium contrast) and five (5) patients underwent one CT scan without IV contrast. In general, complementary studies were conducted in patients with soft tissue tumors of long duration.

The MLL was found in the thigh and trochanteric region of 11 patients; three patients had tumors in their back region, two in their gluteal region, and one in the knee (lateral side).

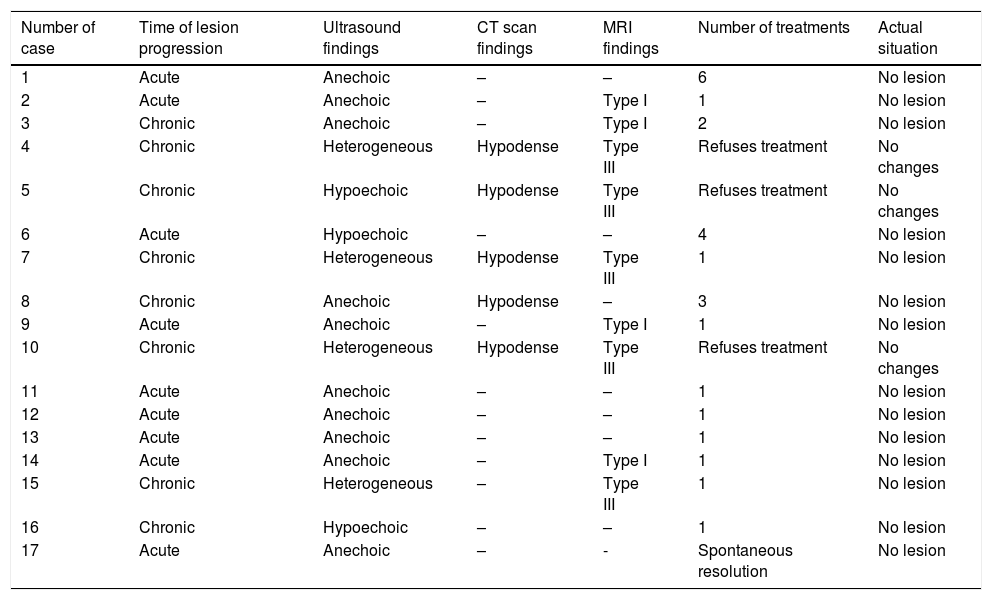

The characteristics of echogenicity and MRI were studied (Table 1).

Time of lesion progression (acute<4 weeks), radiological findings, number of treatments, and actual situation.

| Number of case | Time of lesion progression | Ultrasound findings | CT scan findings | MRI findings | Number of treatments | Actual situation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acute | Anechoic | – | – | 6 | No lesion |

| 2 | Acute | Anechoic | – | Type I | 1 | No lesion |

| 3 | Chronic | Anechoic | – | Type I | 2 | No lesion |

| 4 | Chronic | Heterogeneous | Hypodense | Type III | Refuses treatment | No changes |

| 5 | Chronic | Hypoechoic | Hypodense | Type III | Refuses treatment | No changes |

| 6 | Acute | Hypoechoic | – | – | 4 | No lesion |

| 7 | Chronic | Heterogeneous | Hypodense | Type III | 1 | No lesion |

| 8 | Chronic | Anechoic | Hypodense | – | 3 | No lesion |

| 9 | Acute | Anechoic | – | Type I | 1 | No lesion |

| 10 | Chronic | Heterogeneous | Hypodense | Type III | Refuses treatment | No changes |

| 11 | Acute | Anechoic | – | – | 1 | No lesion |

| 12 | Acute | Anechoic | – | – | 1 | No lesion |

| 13 | Acute | Anechoic | – | – | 1 | No lesion |

| 14 | Acute | Anechoic | – | Type I | 1 | No lesion |

| 15 | Chronic | Heterogeneous | – | Type III | 1 | No lesion |

| 16 | Chronic | Hypoechoic | – | – | 1 | No lesion |

| 17 | Acute | Anechoic | – | - | Spontaneous resolution | No lesion |

Following recommendations from their treating physicians, all patients were offered the possibility of undergoing ultrasound-guided percutaneous treatment, although the possibility of undergoing surgery was discussed as well. Three (3) patients rejected all kinds of treatment, one case resolved spontaneously, and the remaining ones were treated percutaneously.

The percutaneous treatment, always ultrasound-guided and administered after obtaining the patient's written consent, was initially planned through puncture-aspiration of the lesion using a 22-gauge fine needle and placement of compression bandage systems. The second therapeutic step was placing one 6–8F pigtail drainage catheter. In patients with refractory collections, drainage was conducted using one 6F catheter, and sclerodesis procedure through the injection of 5ml of prepared doxycycline solution (20mg/ml) in injectable saline solution. The catheter would remain closed for about 2h and then re-opened to evacuate the collection, remove the catheter, and place the compression bandage. Patients were followed through periodic controls once a month until the complete disappearance of the collection.

All studies and treatments were conducted by authors who agreed on their diagnosis of the images and had 15 years of experience conducting ultrasound-guided interventional radiology.

ResultsTable 1 shows the progression of the lesions ever since the trauma, the radiological characteristics, the number of treatments administered, and the actual situation.

Nine (9) patients said they had suffered from a trauma between 15 days and 2 months prior to presenting to our services (shown in Table 1 as acute cases). The remaining patients (chronic) had a prior history of trauma one or two years ago or could not remember if they had suffered a trauma at all.

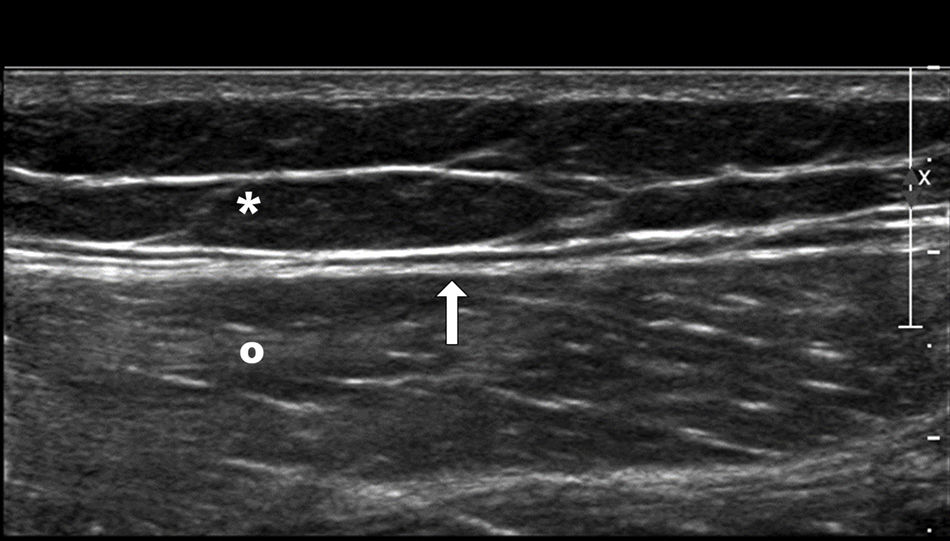

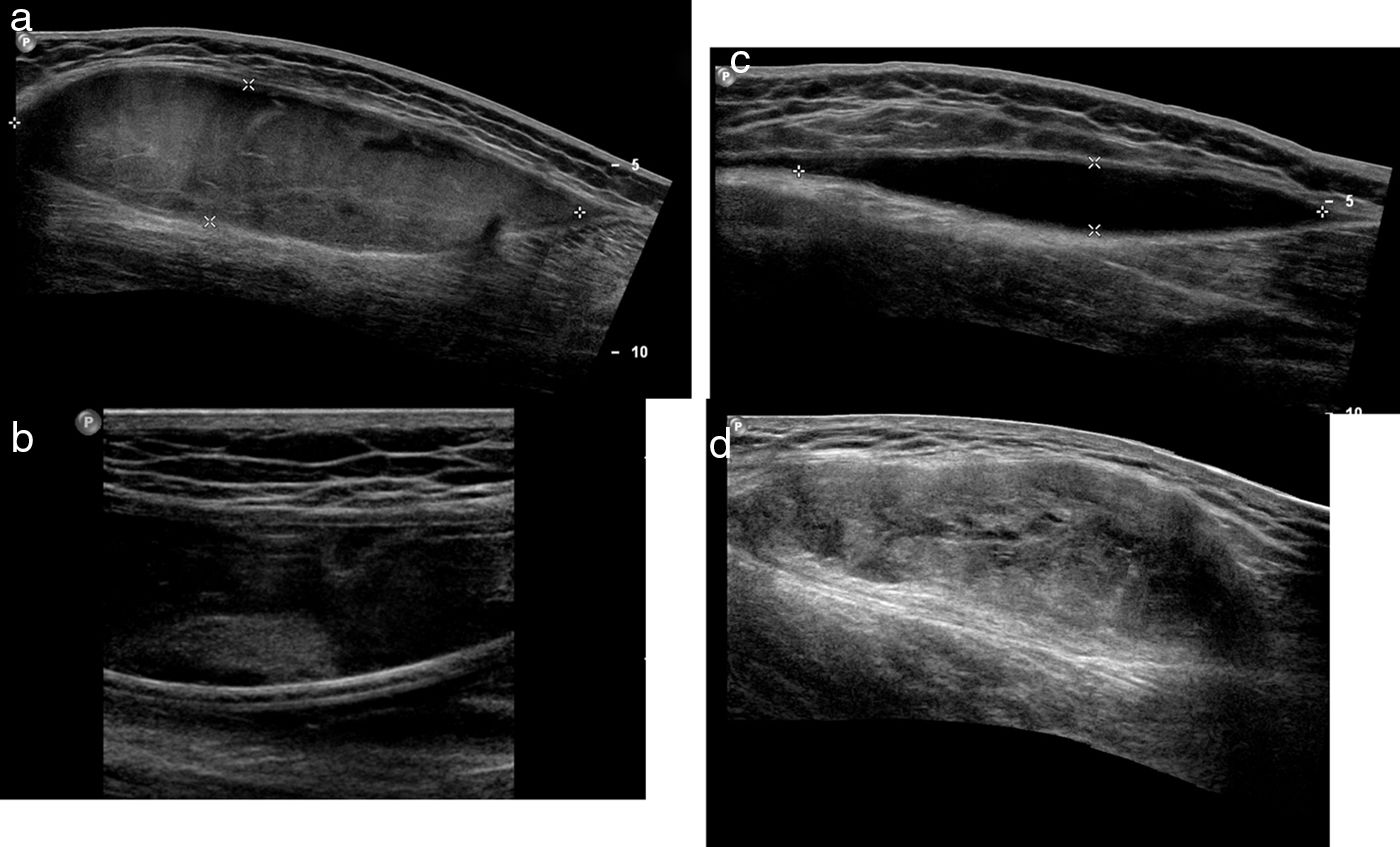

The most common ultrasound characteristic was one fusiform, anechoic collection. All of the acute collections, except for one, were anechoic, and only one collection was chronic (Figs. 1 and 2).

Normal superficial anatomy of the outer side of the thigh. Subcutaneous fat tissue (asterisk), deep fascia (arrow), and vastus lateralis muscle (circle). In the MLL, one trauma—usually a high-energy trauma, causes tangential shear that gives rise to a sudden separation of the skin and the subcutaneous cell tissue of the underlying fascia creating a cavity that ends up filling up with blood and lymph. MLL: Morel-Lavallée lesion.

Progressive stages of the MLL on the ultrasound. At all time, these lesions behave like fusiform lesions of well-established edges. (a) Acute MLL. Acute lesions are usually heterogeneously hypoechoic. (b) On a second time, echogenic nodules representative of fat elements can be detected. (c) Subacute MLL. One-three months after the trauma, the MLL looks like one homogeneously, anechoic, fusiform collection of cystic appearance. (d) Chronic MLL. In the long run (several months or years), the lesion content is usually more complex. They usually behave like lesions of fusiform or lenticular morphology of heterogeneous content and mixed echogenicity. MLL: Morel-Lavallée lesion.

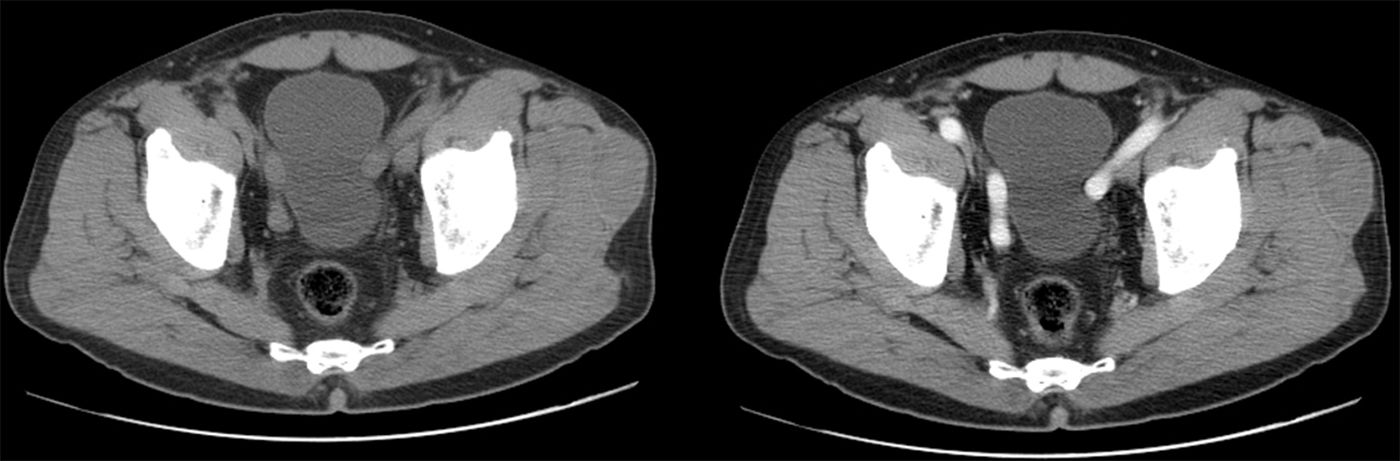

In those cases where a CT scan was conducted, the collection is always described as hypodense (all of them were chronic lesions) (Fig. 3).

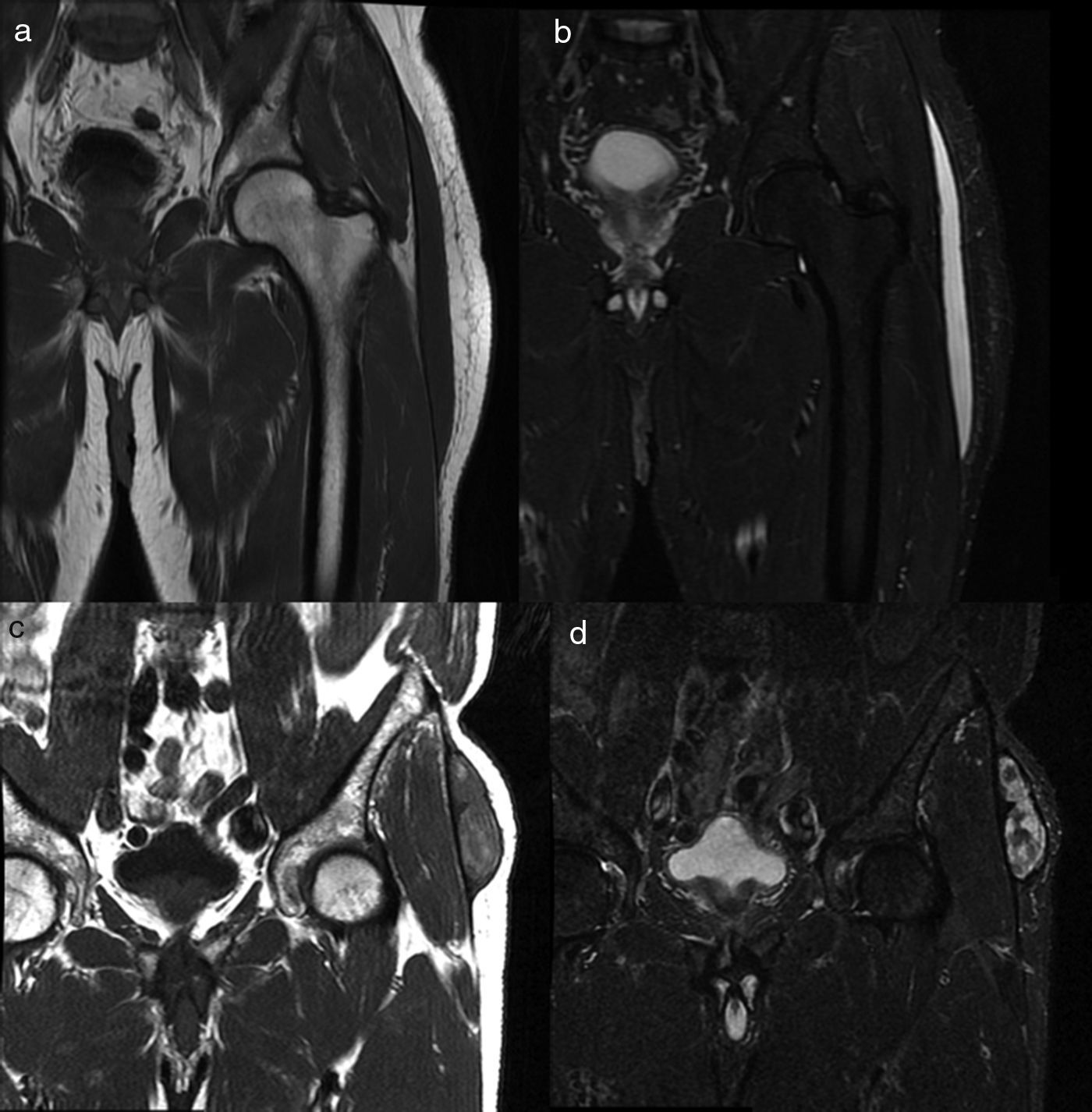

When the MRI was conducted, the lesions were described as type I or type III. All type I lesions were acute, while type III lesions were chronic (Fig. 4).

MRI findings on the MLL. Subacute MLL (a,b). Thirty-three-year-old patient weeks after falling from the bicycle. Images on the coronal plane focused on the left trochanteric region of T1-weighted sequences (a) and T2-weighted sequences with fat suppression (b) on the coronal plane. Most subacute MLLs, as it is the case here, have cystic appearance. Chronic MLL (c,d). Seventy-four-year old patient without known prior trauma. Images on the coronal plane focused on the trochanteric region. Lesion of mixed and heterogeneous signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences (c) and T2-weighted sequences with fat suppression (d). MLL: Morel-Lavallée lesion.

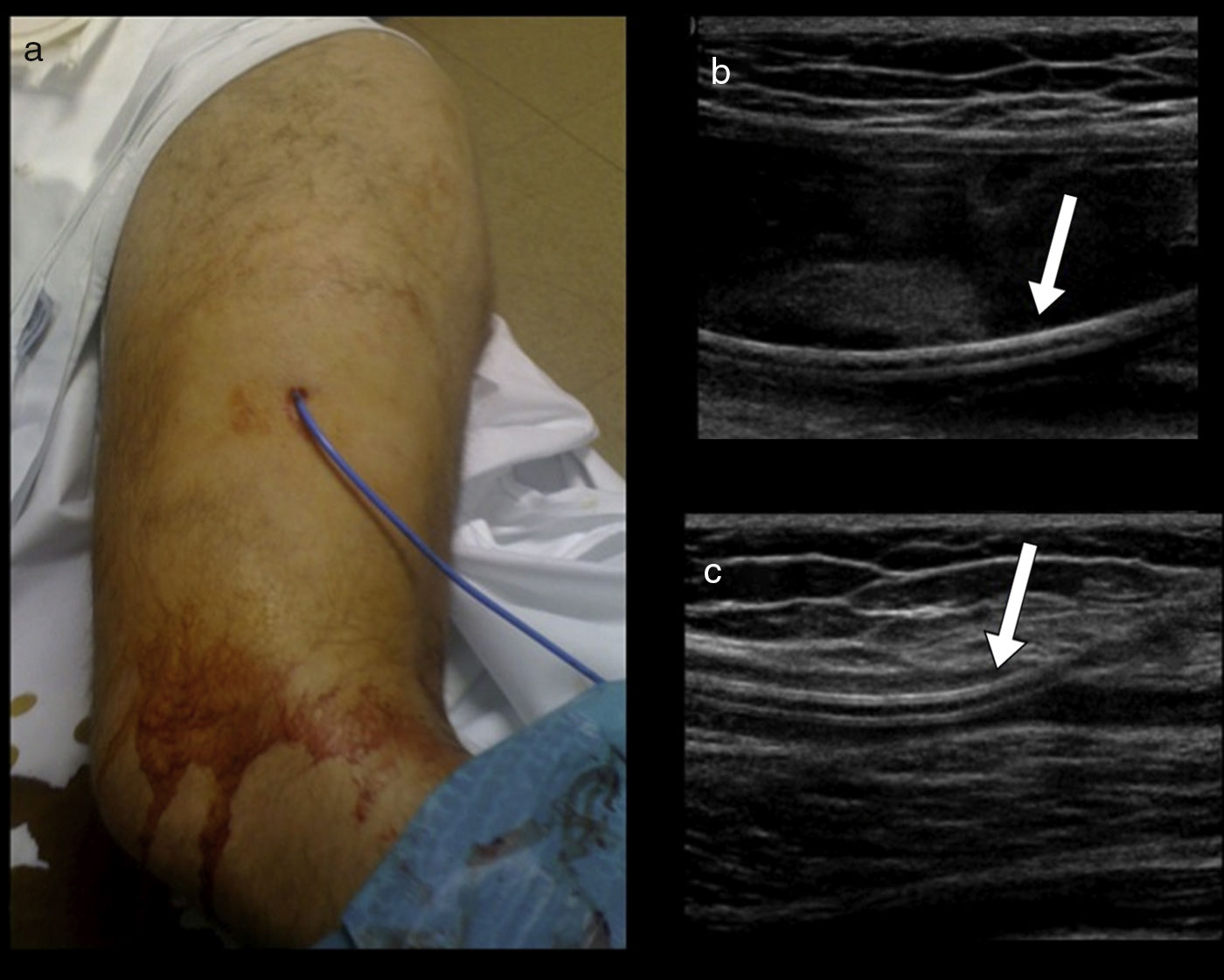

The aspiration procedure followed by compression bandage was conducted in 9 out of 13 patients (Fig. 5). In the remaining four patients, the initial treatment consisted of inserting one 6F- (three patients), or 8F- (one patient) drainage catheter. The procedure had to be repeated in four patients (in three of the patients who underwent aspiration, and in one of the patients inserted with the catheter). In two of the patients, the sclerosis procedure with doxycycline had to be used.

Patient with ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage of one MLL located on the proximal and lateral segment of the thigh. (a) External appearance of the drainage catheter. (b) Catheter (arrow) inside the collection. (c) After the drainage, we can see almost the entire resolution of the collection, and the catheter (arrow) inside the minimal residual collection. MLL: Morel-Lavallée lesion.

Today, the patients remain stable and without collections, at least, after one year of follow-up.

In one case (patient #7), differential diagnosis suggested the possibility that the lesion was actually a tumor, which is why the ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy was conducted, but it did not show any malignant cells.

No infections or other type of adverse reactions followed treatment.

DiscussionThe MLL in one rare lesion,16 whose actual incidence is still unknown5,8; some authors talk about 1.7% in patients with pelvic fractures17 and others about an incidence rate close to 8.3% in patients with traumas in the region of the greater trochanter.18 Although it has usually been associated with high energy traumas, it has also been reported in less energy-intensive accidents, as it happens in all the cases collected in our series.

In the scarce descriptions that we have of the anatomopathological aspect of the lesion, the findings show merely one cystic lesion,5 meaning that it is an entirely clinical and radiological diagnosis. Yet despite the relevant role played by the images in the diagnosis of MLLs, it is still one lesion barely reported and discussed in the radiological literature.2–6,9–13

Neal et al.9 studied the ultrasound characteristics of 21 lesions located in the hip and knee describing that only one third of the lesions were anechoic. In our series, all of the acute lesions (except for one) were anechoic, while chronic lesions were usually hypoechoic or heterogeneous, and consistent with what the aforementioned authors had reported.

We could only find one reference2 with various cases of MLL studied using CT scans, but these are only three cases and the lesion described is hypodense, with a capsule, and fluid-fluid level. In our own experience of five (5) cases, the lesion was homogeneous, hypodense, and with a thin wall. No patient in our series received IV contrast.

The MRI characteristics are far better known and have been described much better in the medical literature.6,10,11 Mellado and Bencardino10 describe five (5) patterns of presentation of MLL that are consistent with the time of lesion progression and presence of infection. Except for one, our four (4) cases with type I-lesions were consistent with acute lesions. On the contrary, the five type III-lesions were chronic lesions.

The differential diagnosis of MLL can include several conditions,3,5 being soft tissue sarcoma13 the most problematic one and can lead to conducting one percutaneous biopsy, as it happened with one of our patients.

Shen et al.19 made a systematic review of the medical literature on the management of MLLs of peripelvic location and found 21 papers on the management of 153 patients, but most of them (140 out of 153 patients) underwent different forms of surgical treatment, and only five (5) were treated with local aspiration. The authors resolve that the treatment of choice for the management of MLL is surgical but that isolated, uncomplicated MLLs can be treated with sclerotherapy.

Conservative therapy with local ice and compression bandage has been suggested as the therapy of choice for the management of MLLs located in the knee region in professional American football players.7 Therapeutic success has been confirmed in more than 50% of the patients.

Tseng and Tornetta17 describe the percutaneous management of MLLs, but this was really a minimally invasive surgery where the lesion was approached with two 2-cm skin incisions through which the drainage and cleaning of the cavity occurred.

The series of 87 MLLs treated in 79 patients of Mayo Clinic16 was reviewed retrospectively and include 25 lesions treated with percutaneous aspiration. Out of the 25, the drainage tube was inserted in 3 lesions only. These authors suggest that only lesions with intact skin and where the amount of aspirated fluid is ≤50ml can be treated percutaneously with aspiration and compression bandage. Even some authors20 say that the relapse rates of percutaneous treatment make this technique simply unacceptable.

We presented 17 cases of MLL, of which 13 were managed through ultrasound-guided percutaneous treatment. In 9 out of the 13 patients, the fine needle aspiration was used, and in 4 patients one drainage tube had to be inserted. In 4 of the patients the procedure had to be repeated several times due to fluid collection reappearance, and in 2 of the patients the sclerosis procedure with doxycycline was used according to protocol, and as described by Bansal et al.15

Our work has several limitations. The first one being the retrospective nature of the study, meaning that it is difficult to know if all patients with potential MLL managed in our hospitals were actually included in the study. On the other hand, we only included patients with MLL without associated skin lesions or fractures, which is why we cannot rule out the possibility that other patients with MLL who underwent surgical procedures to resolve such lesions also received treatment for their MLL. The small size of the sample is not powerful enough to be able to conduct statistical analyses and draw conclusions.

In sum, the MLL is a relatively rare condition, but with which radiologists should be familiar. On the ultrasound, its presentation is that of one fusiform, anechoic lesion; on the MRI it looks hypointense on the T1-weighted sequences, and highly hyperintense on the T2-weighted sequences when the lesion is acute (less than a month), or with a more heterogeneous appearance when it is chronic.

In our own experience, we suggest that when they are not accompanied by skin lesions or fractures, the management of MLLs should be done percutaneously with ultrasound-guided aspiration or drainage, and compression bandage, keeping the sclerosis procedure with doxycycline for the most refractory forms of the disease.

Authors’ contribution- 1.

Manager of the integrity of the study: JMV.

- 2.

Study idea: JMV, MJDC and ABH.

- 3.

Study design: JMV.

- 4.

Data mining: JMV, MJDC and ABH.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: JMV, MJDC and ABH.

- 6.

Statistical analysis: JMV.

- 7.

Reference: JMV and MJDC.

- 8.

Writing: JMV.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant remarks: JMV, MJDC and ABH.

- 10.

Approval of final version: JMV, MJDC and ABH.

The authors declare no conflict of interests associated with this article whatsoever.

Please cite this article as: Martel Villagrán J, Díaz Candamio MJ, Bueno Horcajadas A. Lesión de Morel-Lavallée: diagnóstico y tratamiento con técnicas de imagen. Radiología. 2018;60:230–236.