Edited by: Dr. Tomás Ripollés González - Servicio de Radiodiagnóstico, Hospital Universitari Doctor Peset, València, España

More infoImaging techniques play a fundamental role in the initial diagnosis and follow-up of inflammatory bowel disease. Intestinal ultrasound has high sensitivity and specificity in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease and in the detection of inflammatory activity. This technique enables the early diagnosis of intra-abdominal complications such as stenosis, fistulas, and abscesses. It has also proven useful in monitoring the response to treatment and in detecting postsurgical recurrence. Technical improvements in ultrasound scanners, technological advances such as ultrasound contrast agents and elastography, and above all increased experience have increased the role of ultrasound in the evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract. The features that make ultrasound especially attractive include its wide availability, its noninvasiveness and lack of ionising radiation, its low cost, and its good reproducibility, which is important because it is easy to repeat the study and the study is well tolerated during follow-up. This review summarizes the role of intestinal ultrasound in the detection and follow-up of inflammatory bowel disease.

Las técnicas de imagen desempeñan un papel fundamental en el diagnóstico inicial y seguimiento de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. La ecografía intestinal tiene alta sensibilidad y especificidad en la sospecha de la enfermedad de Crohn, en la detección de actividad inflamatoria y permite el diagnóstico temprano de complicaciones intraabdominales, como estenosis, fístulas y abscesos; además, ha demostrado su utilidad en la monitorización del tratamiento y en la recurrencia posquirúrgica. El desarrollo técnico de los equipos de ecografía, la incorporación de avances tecnológicos como el contraste ecográfico o la elastografía y, sobre todo, una mayor experiencia, han impulsado su papel en la evaluación de la patología del tubo digestivo. La ecografía es particularmente atractiva gracias a su amplia disponibilidad, su inocuidad, bajo coste y buena reproducibilidad, ya que puede repetirse de forma fácil y bien tolerada por el paciente durante el seguimiento. Esta revisión resume el papel de la ecografía intestinal en la detección y seguimiento de pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal.

The term inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), whose main characteristics are their chronic nature and the occurrence of flare-ups. IBD reaches its peak incidence between the ages of 10 and 30, but it can occur at any age.1 Approximately 10% of cases are diagnosed as indeterminate colitis as they share characteristics of the two disorders.

UC is characteristically confined to the mucosal layer of the colon and extends from the rectum proximally in a continuous and regular manner. In CD, however, the inflammation is transmural and segmental, with alternating healthy and diseased stretches of intestine. Although CD can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, the terminal ileum is the most common location, affecting up to 70% of patients.2

Colonoscopy is the standard test in the case of UC, but for patients with CD it only assesses the inflammatory activity and extent of the disease in the colon and the last few centimetres of the terminal ileum. It does not suitably assess transmural complications. It has been reported that the colonoscopy is incomplete in up to 20% of cases, due to the severity of the disease or the presence of strictures, or because it extends to inaccessible segments adjacent to the terminal ileum.1

This article aims to provide a broad overview of the real role of intestinal ultrasound in the detection of IBD and its complications, as well as an analysis of its use in monitoring patients with IBD.

Ultrasound in Crohn's diseaseAs mentioned, CD is a transmural disease which cannot be properly assessed by endoscopy, as it only allows visualisation of the mucosa. For that reason, a cross-sectional imaging technique is recommended as a supplement to colonoscopy.1 Although ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) do not detect subtle mucosal lesions, they do suitably assess transmural involvement, extramural extension of the disease and the presence of complications. As such, these techniques have taken on a central role in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with CD.3 Indeed, a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses as well as the latest consensus guidelines of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) have shown that the three cross-sectional techniques have comparable diagnostic accuracy for the initial assessment of CD, assessment of disease severity and activity, and detection of its main complications: strictures, fistulas and abscesses.3–5

CD is a chronic inflammatory disease characterised by flare-ups, with alternating periods of relapse and remission. The disease has a wide range of clinical manifestations; the most common are abdominal pain and diarrhoea.3,6 In view of the recurrent nature of the disease, frequent reassessment is recommended to ensure optimal management. A significant proportion of patients are diagnosed at an early age, with a maximum incidence between the ages of 15 and 25.7 The need for repeated assessment with imaging techniques and the prevalence in young patients both necessitate the use of radiation-free cross-sectional techniques. Hence, MRI and ultrasound have become the two leading methods in routine clinical practice. In recent years, both have been shown to have similar diagnostic performance and aid in the management of patients with CD; either can be used at different stages of the disease.3

The ultrasound technique and the process of making a diagnosis from findings are described in detail in a previously published article.8

Advantages and limitationsUltrasound has several advantages over MRI and CT, as it does not use ionising radiation, it is cheap and accessible, it is well-tolerated by patients, it does not require a specific oral preparation and it also has the potential for higher spatial resolution (using high-frequency transducers). The excellent tolerance of ultrasound means it can be repeated as often as necessary. This is especially important in monitoring treatment, as the more the treatment can be adjusted according to the findings of these tests, the more likely the goal (mucosal healing) is to be achieved.9

As with other diagnostic techniques, the performance of ultrasound depends on the operator, and the results are influenced by the quality of the ultrasound machine, the experience of the ultrasonographer, the probes used and the patient's constitution.4,10–14 However, a study assessing the interobserver variability of intestinal ultrasound found a good degree of agreement in measurement of bowel wall thickness, colour Doppler grade, presence of lymphadenopathy and detection of strictures—all of which are important factors in diagnosing the disease and assessing inflammatory activity.14

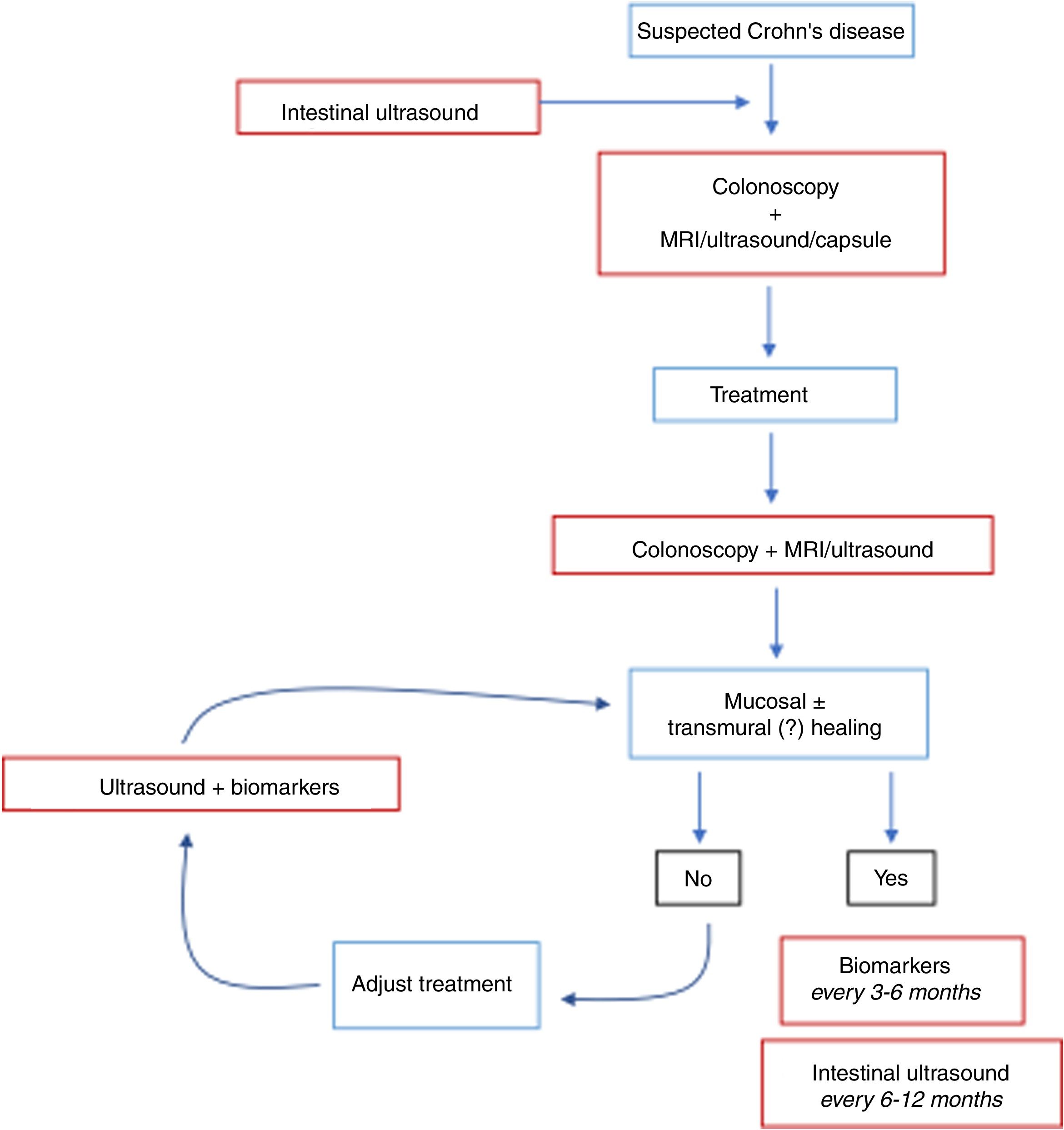

Initial diagnosisThe results in the literature show that ultrasound is an accurate technique in the initial approach for patients with bowel symptoms suggestive of CD. In published systematic reviews, ultrasound has a sensitivity of 85%–97% and a specificity of 83%–97% for the diagnosis of CD.4,5,15–18 Similar results have been obtained in meta-analyses of MRI. In addition, studies comparing the two techniques have mostly shown similar performance,11,19,20 although the METRIC study, which is the most methodologically appropriate,21 found MRI to be superior by 10% to ultrasound in determining the extent of the disease in the small intestine. Due to its high negative predictive value, ultrasound could be accepted as a first-line tool in diagnosing or ruling out CD of the small intestine in adults and children (Fig. 1). In children in particular, it could be the preferred imaging technique, as other imaging procedures are sometimes more complex to perform. Ultrasound plus ileocolonoscopy has been found to be the most accurate and least expensive strategy in suspected cases of CD.22

The diagnosis of CD is mainly based on the measurement of bowel wall thickness. A thickness of 3 mm or more should be used as a cut-off point for CD detection when high sensitivity is preferred, while a thickness of 4 mm or more should be chosen if the preference is for high specificity.23

Sensitivity varies depending on the location of the disease, with higher values for anatomical areas easy to access for ultrasound, such as the terminal ileum and left colon, and lower for the rectum, proximal bowel tracts (jejunum) and deep pelvis.4,19,21,24,25 Diagnostic accuracy also depends on the disease severity. The more severe the inflammatory lesions, the more accurate the diagnosis.

The ECCO/ESGAR guidelines support the use of intestinal ultrasound and MRI for extension and localisation studies.3 MRI shows better agreement with the surgical findings in the assessment of the length of the affected segment, while ultrasound underestimates the extent, especially when the segment is very long.12

Basic ultrasound findingsUltrasound can be used to demonstrate the abnormal findings and complications of CD and help classify each patient into one of the three disease subtypes (inflammatory, fistulising, or stricturing), thus guiding appropriate treatment. Findings can be divided into mural, extramural and transmural complications.

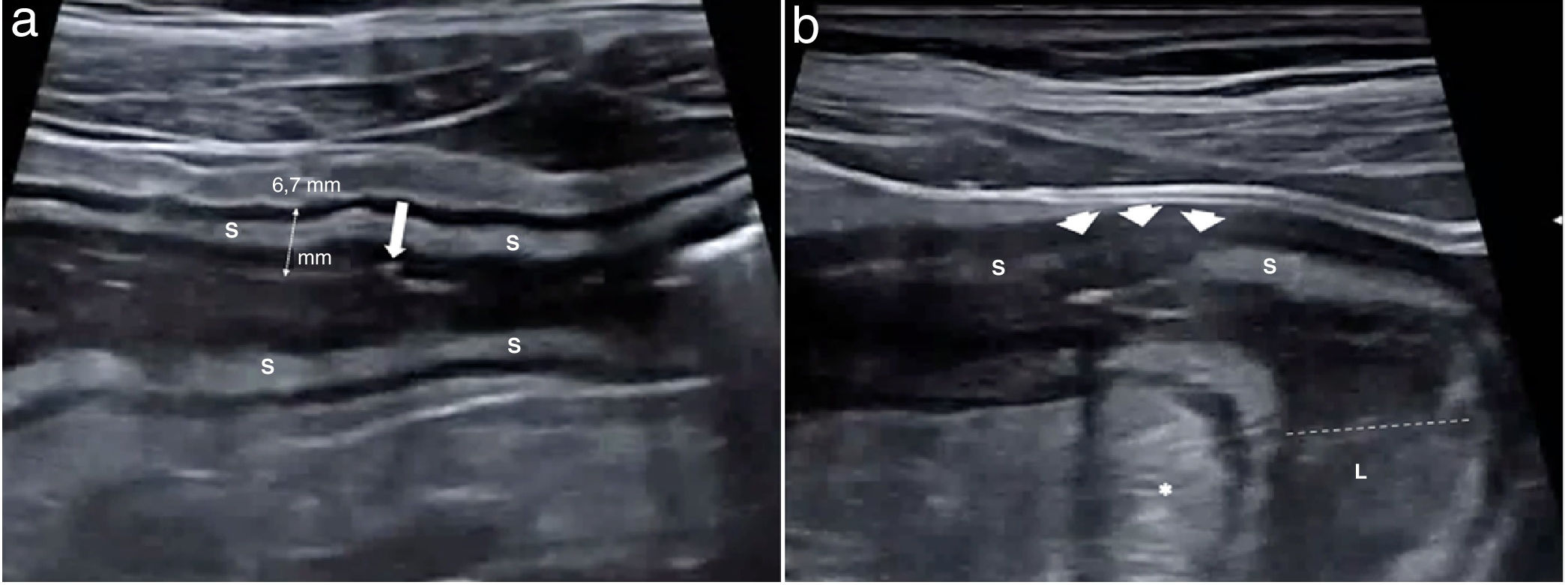

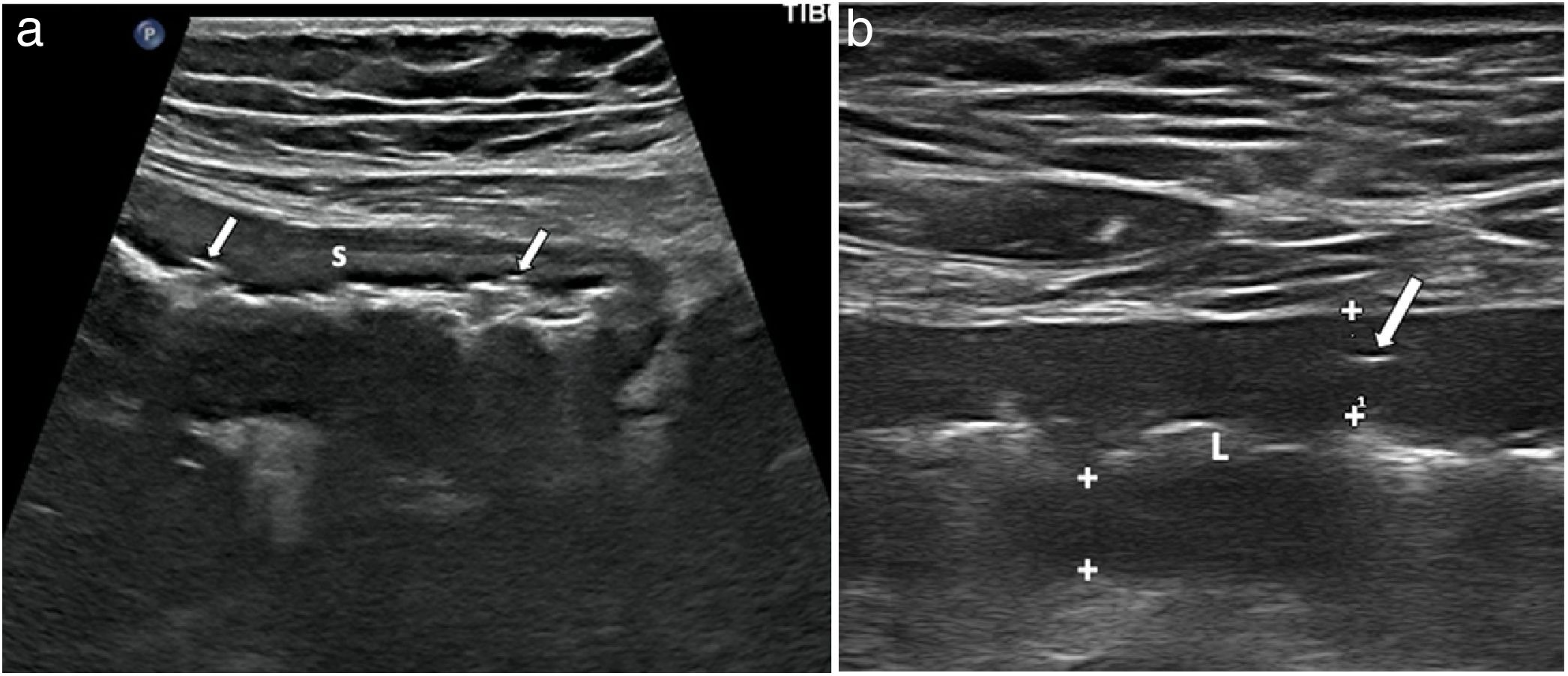

Mural findingsWall thickeningWall thickness is the most robust ultrasound parameter for diagnosing and assessing disease activity, and also a parameter that shows high interobserver agreement.14,24 Measurements should be taken on the anterior wall of the loop, along a longitudinal axis, avoiding mucosal folds (Fig. 2a). Wall thickening in CD is generally moderate, accompanied by stiffness of the affected loop and decreased or absent peristalsis. The bowel wall is significantly thicker in patients with active disease than in those with inactive disease.25

a) Crohn’s disease with wall thickening measuring 6.7 mm and preservation of the layer structure. The third layer or submucosa (S) is prominent. A linear echogenic image in the muscularis mucosae (arrow) corresponding to a superficial ulcer is identified. b) Alteration of the echotexture of the wall. Segment of the ileum of a CD patient with marked inflammatory activity. A focal alteration of the layered structure can be seen, with abrupt interruption (arrow heads) of hypoechoic submucosa (S). Some studies have shown a correlation between this finding and the presence of deep ulcers on endoscopy or in the surgical specimen. Creeping fat (*) and dilation of the lumen (dotted line) proximal to the most affected area (L) are also identified, indicating the presence of a stricture.

In CD without complications the stratified appearance is preserved. There is sometimes a significant increase in the thickness of the echogenic submucosa over the other layers. Focal or extensive loss of stratification may occur in cases of severe acute disease, possibly due to the presence of ulcerations reflecting increased disease activity (Fig. 2b). In fact, a correlation has been found between loss of stratification and endoscopic disease activity or a higher risk of needing surgery.26,27 However, it can sometimes be seen in very advanced quiescent disease, especially of the left colon (severe fibrosis).12

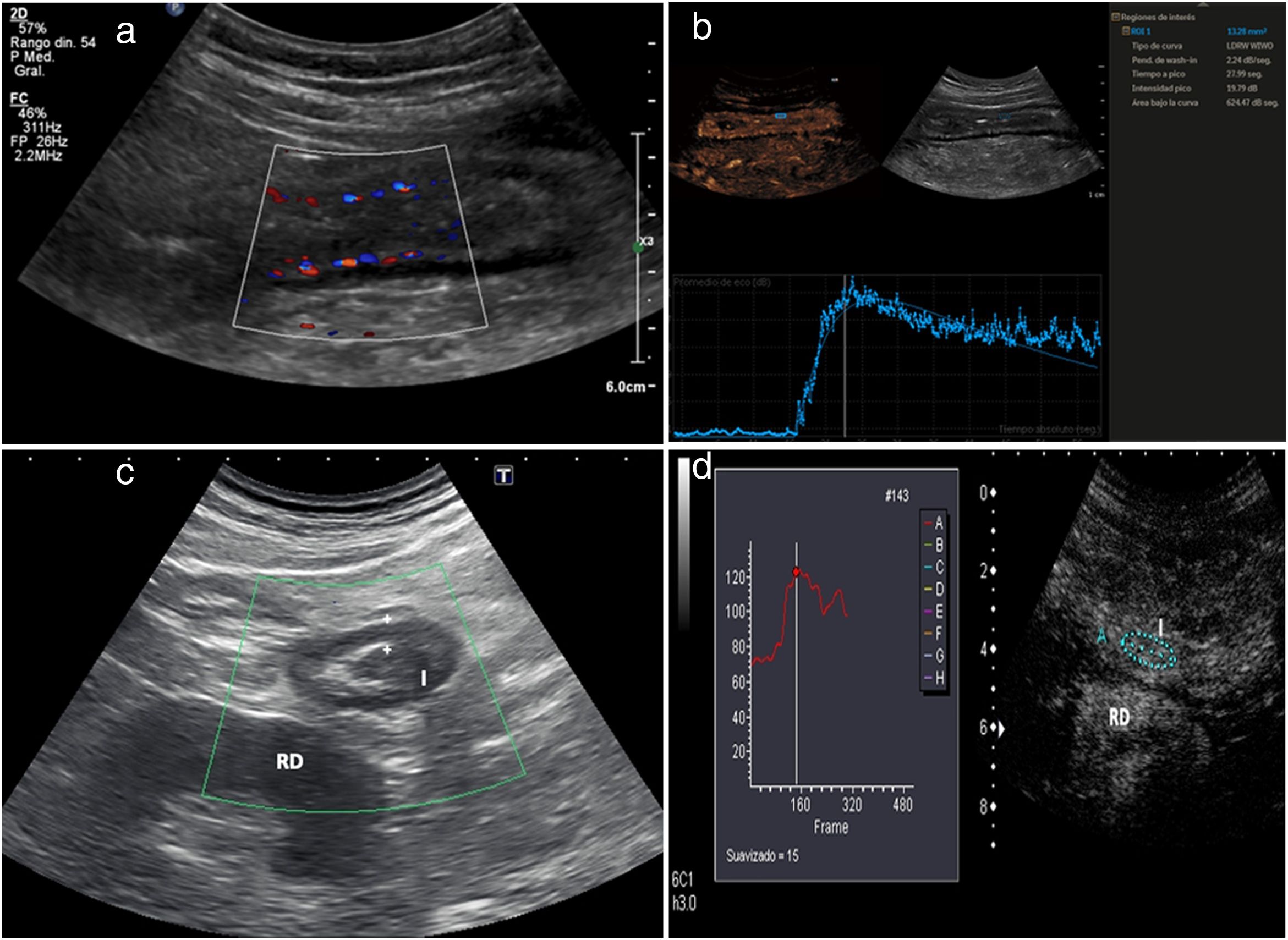

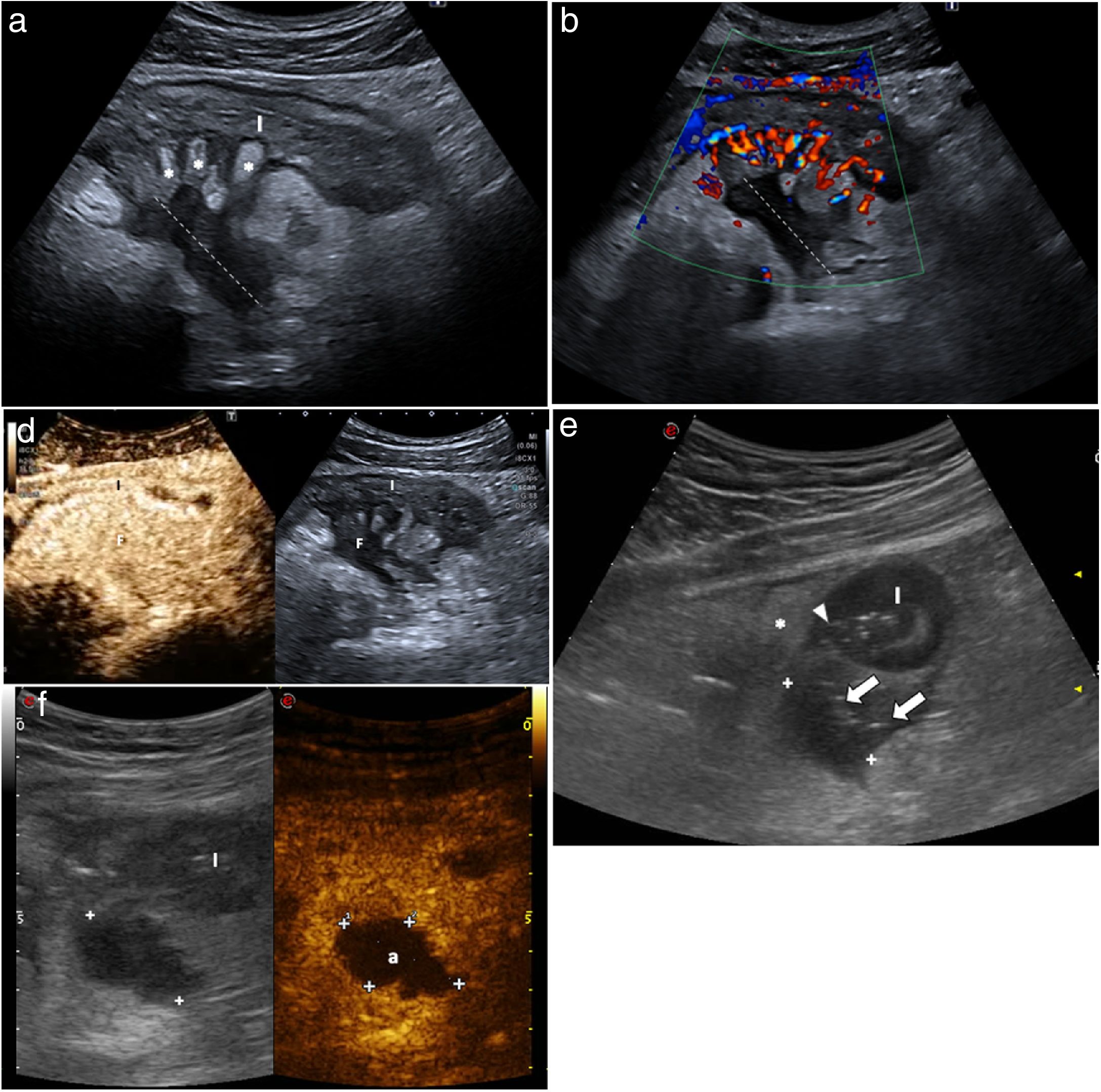

Hyperaemia with colour DopplerWall hyperaemia detected with colour Doppler ultrasound is another finding of inflammatory activity.8 Increased bowel wall vascularisation (grade 2 or grade 3 on the modified Limberg scale by colour Doppler) is correlated with histological, endoscopic and clinical activity.28–35 In a recently published series, grade 2−3 hyperaemia showed a diagnostic specificity in excess of 90% for severe endoscopic disease and a positive predictive value of 97% for the presence of ulcers on endoscopy (Fig. 3a).31 However, the persistence of wall hyperaemia may be associated with an increased risk of disease flare-up.33

a) Patient with thickened ileum (I) and abundant mural colour Doppler signal (grade 2); these findings suggest active disease. b) Following contrast injection, the wall of the ileum (I) is seen to enhance with a submucosal predominance. Region of interest (ROI) located on the posterior wall of the loop. The time-intensity curve shows a peak intensity of 19.79 dB (intensity >18 dB is associated with active disease). The contrast study suggests active disease and is consistent with the thickness and interpretation of the colour Doppler imaging. Colonoscopy showed abundant wall ulcers. c) Patient with Crohn’s disease, having previously undergone surgery, with neoterminal ileum wall thickening (I) and absence of colour Doppler signal (grade 0). Ultrasound activity is indeterminate, as the thickness suggests active disease, but this is not confirmed by colour Doppler. Right kidney (RK). d) Following injection of ultrasound contrast there is intense enhancement. The ROI is in the bowel wall. The time-intensity curve shows an increase in enhancement of 65% (an increase >46% is considered active disease). The colonoscopy showed signs of severe recurrence (Rutgeerts 3). Note: the quantitative measurements obtained with the software packages of the different commercial ultrasound systems are not interchangeable.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) increases the sensitivity of colour Doppler in detecting increased wall vascularisation, overcoming its limitations even when assessing the deep intestinal loops. Several studies have shown that wall enhancement is significantly better than thickness or colour Doppler in the assessment of disease activity, using endoscopy as a reference test25,31 (Fig. 3b). It is particularly useful in patients with abnormal wall thickening in whom the Doppler study shows no wall hyperaemia.31 Different studies and meta-analyses have shown that it is highly precise in detecting endoscopic activity, with a sensitivity of 87%–97% and a specificity of 67%–91% in differentiating between activity and endoscopic remission.16,17,25,31,36 However, the use of contrast has limitations in standard clinical practice; the main limitation is the heterogeneity in quantification curves among different ultrasound systems.23 For example, in some systems, an increase in peak intensity greater than 46% is considered active disease,25 while in others activity is measured by peak intensity, with more than 15 dB indicating activity and more than 18 dB indicating moderate activity.37

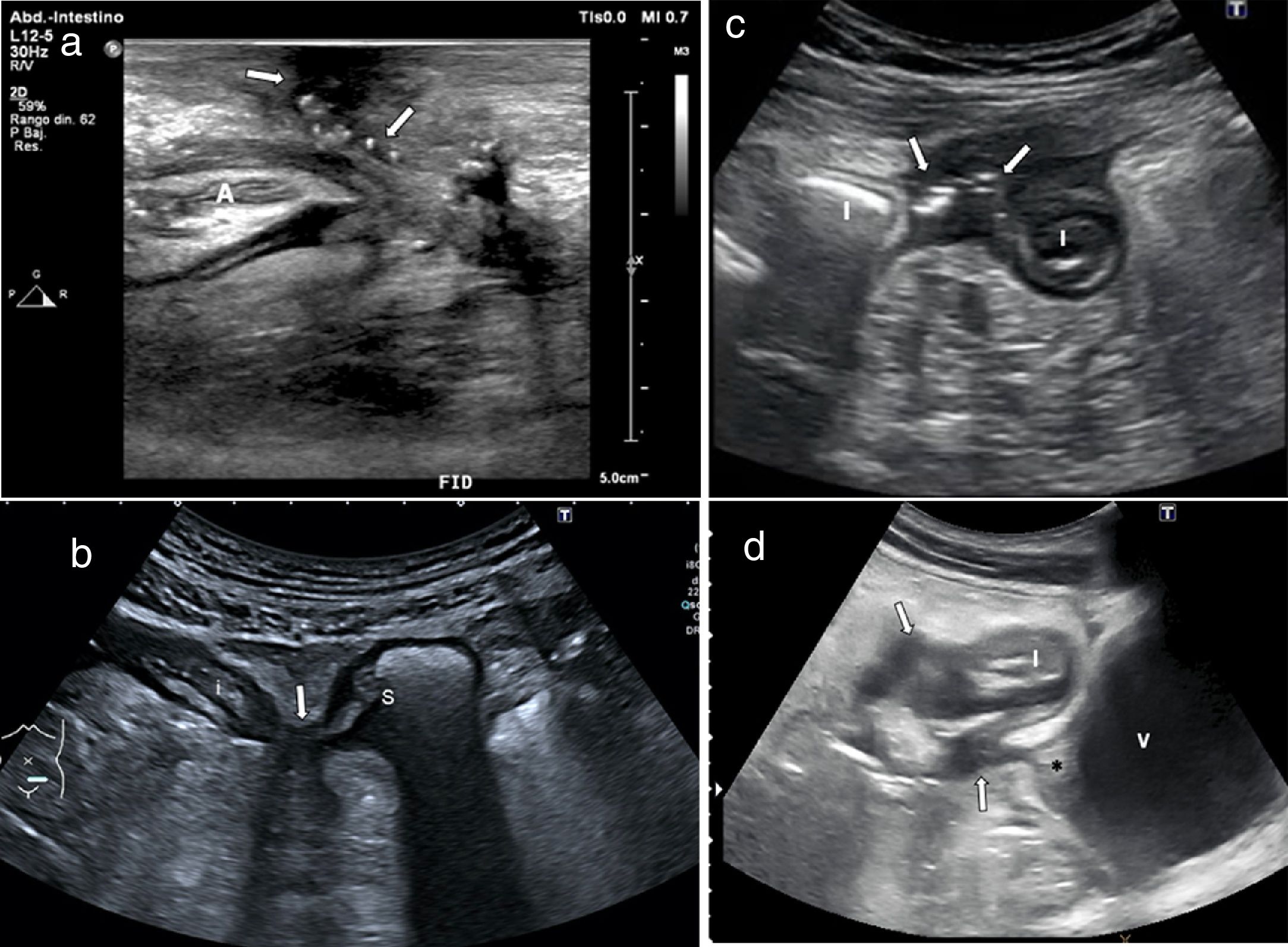

Wall ulcersWall ulcers are recognised as irregularities in the inner layer of the wall or by hyper-echogenic images which extend into the wall to varying degrees (Fig. 4). The diagnostic ability of ultrasound in detecting ulcers may be even higher than that of MRI, as demonstrated by two recently published series, which reported a diagnostic accuracy of 81%–96%, compared to the combination of colonoscopy and MRI or surgical specimens.19,38

a) Longitudinal section of terminal ileum segment revealing thickening of the wall, especially submucosa (S) and irregularity of the surface of the lumen, showing two millimetre-sized hyperechogenic foci in the thickness of the muscularis mucosae (arrows), corresponding to superficial ulcers. b) Longitudinal slice of ileum, with linear transducer, showing hypoechoic wall (wall thickness, between markers), with linear echogenic imaging inside due to deep ulcer (arrow). L: echogenic central bowel lumen.

This is characterised by the presence of a homogeneous increase in the echogenicity of the fat surrounding an affected bowel segment (Figs. 2 and 5). This finding has been associated with the presence of fistulas and abnormal wall thickening.39 However, it is a finding which may also persist in patients in remission.39

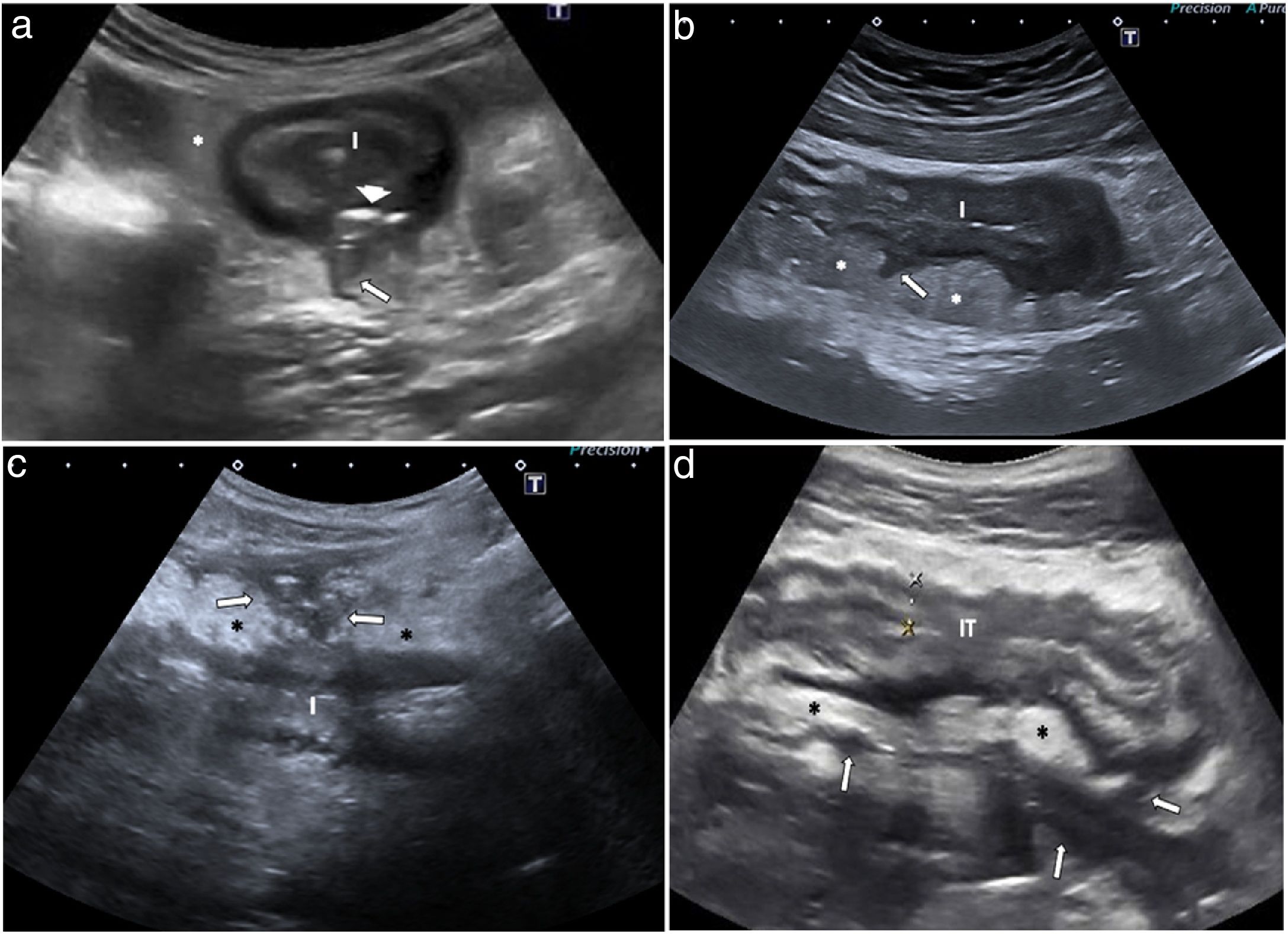

Ultrasound images of fissures in 4 patients with Crohn’s disease, a finding reflecting severe transmural inflammation. a) Hypoechoic irregularity of the serosal surface (arrow) of the ileum, and echogenic images in the muscle layer due to deep ulcers (arrow head). Creeping fat (*). b) Hypoechoic irregularity (arrow) of the posterior wall of the thickened ileum (I), which also shows loss of structure in wall layers. c) Blind-end hypoechoic tracts with gas bubbles (arrows) anterior to a thickened ileal loop (I). d) Thickened terminal ileum (TI) with multiple irregular deep hypoechoic tracts (arrows) passing through the inflamed mesenteric fat (*).

An increase in flow in the mesenteric vessels which supply the wall can be seen with colour Doppler, or after injection of contrast, described as the "comb sign". The identification of mesenteric hyperaemia is non-specific for any intestinal inflammatory process, but in the context of CD, it is a marker of bowel segments with active inflammation.

Lymph nodesThis finding may be identified in up to 25% of patients with CD.40,41 However, the presence and number of lymph nodes is more common in childhood, at the onset of the disease and in patients with fistulas and abscesses. The enlarged lymph nodes may disappear after treatment.40

Sinus tracts and fissuresAs the disease progresses, the inflammation caused by CD can spread deep into the bowel wall. Hyperechoic wall tracts, which represent linear ulcerations, pass through the intestinal wall and extend beyond the outer surface, thus becoming extramural. Initially, they are seen as subtle hypoechoic irregularities (fissures) in the outer margin of the loop or serosa (Fig. 5).41–43 Fissures can extend into hyper- or hypoechoic tracts through the mesentery, and are known as sinus tracts when they have a blind end in the mesentery (Fig. 5).44–46 Fissures and sinus tracts, probably resulting from microperforations, reflect severe transmural inflammation.

Transmural complicationsFistulasThe inflammatory phenotype is the most common at presentation of the disease, but up to a third of CD patients develop a penetrating disease during their lifetime.47 Fistulas are one of the characteristic findings of the disease and derive from wall fissures and sinus tracts.

A fistula is a connection between two structures with epithelialised surfaces and can occur between small bowel loops (enteroenteric), between the small intestine and the colon (enterocolic) or between the intestine and the skin (enterocutaneous). Less commonly, they can also affect other organs such as the bladder (enterovesical), vagina (enterovaginal) or ureter.11,40,41,47,48 Fistulas are identified as hypoechoic tracts extending from the loops to other bowel segments or other organs, but if they have gas they may show echogenic foci with or without movement within the tract (Fig. 6).

Fistula images of 4 patients with Crohn's disease. a) Enterocutaneous fistula: thickening of the wall of the anastomotic loop (A) in the right iliac fossa (RIF) in a patient having previously undergone surgery, with a fistulous tract from the anastomosis to the skin surface and gas bubbles along the tract (arrows). b) Enteroenteral fistula: axial slice of two intestinal loops (I) with thickening of the wall and fistulous tract with gas bubbles between them (arrows). c) Enterosigmoid fistula between the ileum (i) and sigmoid colon (S), with approximation and retraction of both structures (arrow). d) Enterovesical fistula: cross-section of thickened ileum (I) in contact with the bladder (V), with multiple hypoechoic fistulas (arrow), one running towards the bladder dome which shows thickening and retraction of the wall (*).

The sensitivity of ultrasound in the diagnosis of fistulas is 67%–87%, similar to that of CT or MRI, with a specificity of 90%–100%.4,24,49 The latest consensus guidelines from the ECCO and the ESGAR for the diagnosis and follow-up of IBD recommend intestinal ultrasound as one of the imaging techniques to assess fistulising complications.3

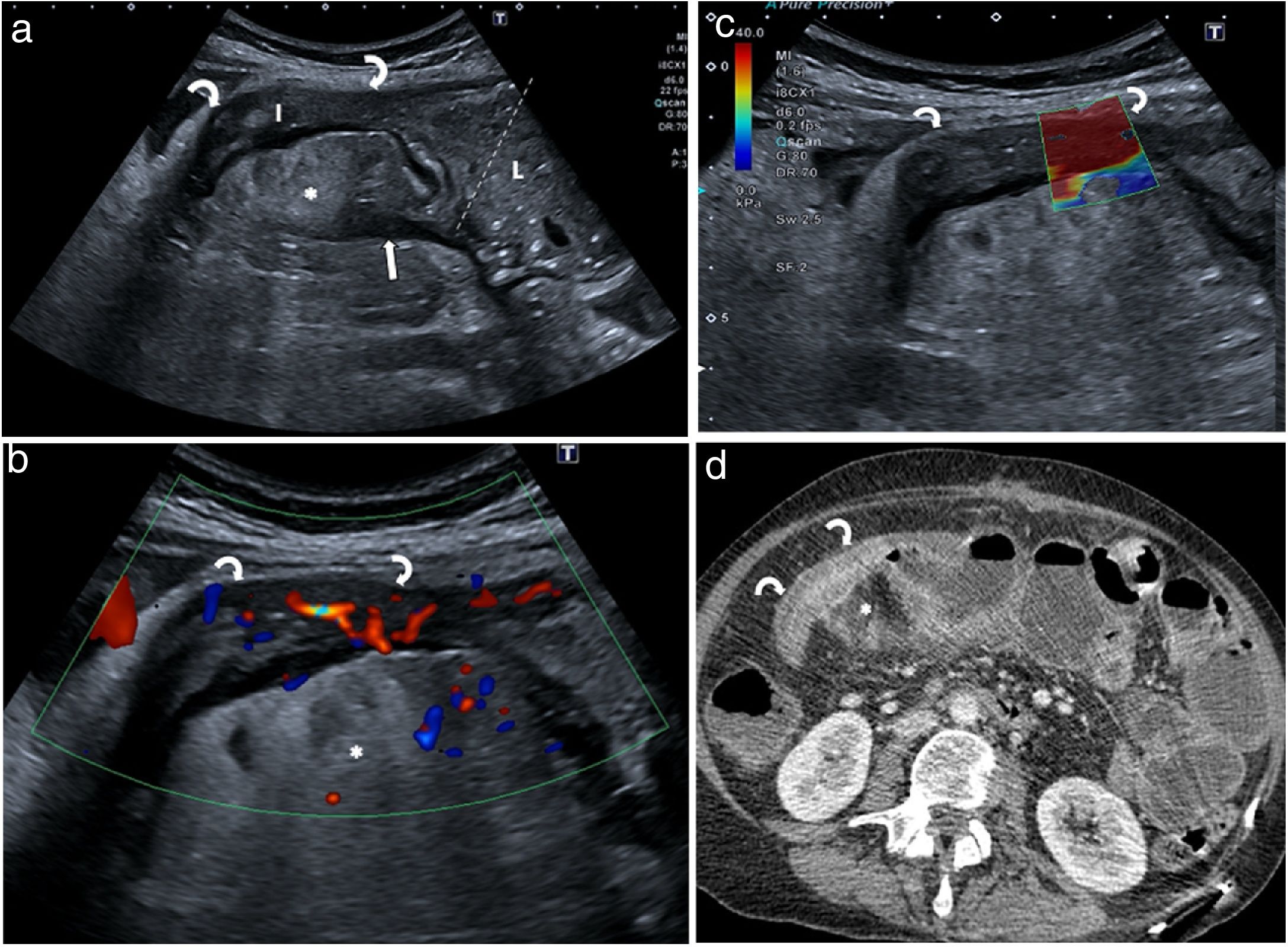

Inflammatory masses (phlegmon and abscess)Inflammatory masses, whether phlegmons or abscesses, can be associated with a fistulous tract. Abscesses appear on ultrasound as hypoechoic or anechoic masses with posterior reinforcement and well-defined thick walls which may contain gas. Phlegmons appear as hypoechoic masses with poorly defined margins and no identifiable wall.6,11,41,43,48 However, abscesses and phlegmons can look similar on B-mode ultrasound. Differentiation is important when deciding on medical treatment (antibiotics with or without percutaneous drainage) or surgical treatment. It also aids in introducing specific treatments for the disease; for example, due to the risk of septic complications, the presence of abscesses should be ruled out before starting biological treatment.

The use of contrast-enhanced ultrasound allows accurate differentiation between the two, as with a phlegmon there is diffuse enhancement of the lesion, while with an abscess a central avascular portion can be seen and enhancement is peripheral (Fig. 7).50 The use of contrast does not increase the detection of inflammatory masses, but it does improve the specificity of the diagnosis of abscess, avoiding false positives. It also allows size to be determined more precisely.50 Therefore, when an inflammatory mass is detected by ultrasound, it should be assessed with contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Contrast may also be useful for monitoring the resolution of the abscess.23,24

Utility of contrast in differentiating between phlegmon (a, b and c) and abscess (d and e). a) Mesenteric phlegmon. The thickening of an ileal loop (I) and a mesenteric hypoechoic inflammatory mass (dotted line) are observed. Note the inflamed echogenic fat (*) disrupted by hypoechoic tracts which represent fissures. b) Colour Doppler ultrasound shows grade 3 hyperaemia, with an increase in wall and mesenteric vessels (comb sign). The inflammatory mass shows no macroscopic vessels, suggesting an abscess. c) Following injection of ultrasound contrast, there is uniform enhancement of the mass, indicating that it is a phlegmon. Creeping fat (*). d) Abdominal abscess. Cross-section of thickened intestinal loop (I) with deep ulcers (arrow head) going through the wall. There is a hypoechoic mass (between markers) with small bubbles of gas inside (arrows). Creeping fat (*). e) After intravenous contrast administration there is no enhancement in the mass (between marks), allowing a definitive diagnosis of an abscess (a). Phlegmon and abscess often have an overlapping hypoechoic appearance in the B-mode ultrasound study; therefore, the use of intravenous contrast is essential in distinguishing them.

The sensitivity of ultrasound in diagnosing abdominal abscesses ranges from 81% to 100%, with specificities of 92%–94%, similar to those of CT and MRI. However, certain anatomical areas such as the pelvis are difficult to assess by ultrasound due to depth and presence of gas which can obscure lesions.23,49 Ultrasound can be used as an initial imaging method and CT or MRI can be reserved for use in resolving uncertain diagnoses or at centres without suitable ultrasound experience.

StricturesVarious systematic reviews and position statements affirm that ultrasound, CT and MRI have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of small-intestine and colon strictures, with similar diagnostic accuracy.3,4,51 In a recently published systematic review, ultrasound sensitivity was 80% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 75.2%–84.2%) and specificity was 95% (95% CI: 89.7%–99.8%).24 The diagnostic ability of ultrasound in detecting strictures increases if oral contrast (250−500 ml of polyethylene glycol) is used; this technique is known as small intestine contrast ultrasonography (SICUS). Diagnostic sensitivity is increased by 10% for a single stricture and by 20% when there are two strictures.24

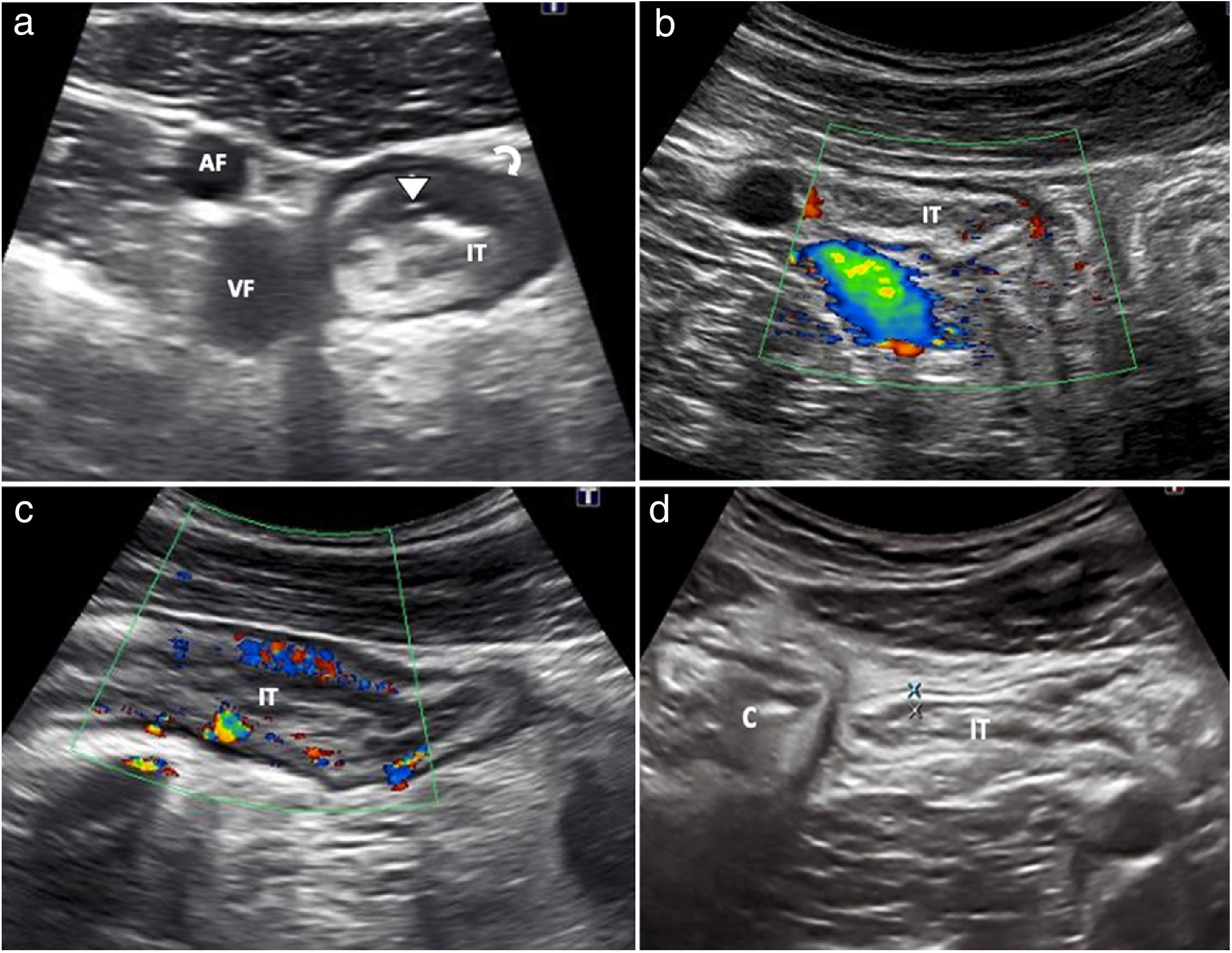

If the scan is performed without oral contrast, the stricture is seen as an aperistaltic intestinal segment with a thickened and rigid wall, narrowing of the lumen and a dilated proximal segment, which may be fixed with no movement or with hyperperistaltic movements (Fig. 8).12,13

Bowel obstruction due to stricture. a) Segment of intestine (I) with thickened strictured walls (curved arrows) and dilation of the lumen (L) of the previous loop (between markers). Mesenteric blind fissure (arrow). Creeping fat (*). b) Colour Doppler study showing grade 2 hyperaemia, suggesting inflammatory stricture. c) Elastography examination of the stricture identifies a predominance of red colouration, indicating a fibrous component. d) Intravenous contrast CT scan showing good correlation with ultrasound imaging. The surgical specimen study indicated mixed stricturing, with a high degree of inflammation and fibrosis.

Most stricturing is mixed, and only a small percentage is purely inflammatory or fibrotic.52 Several studies have shown that loss of the layered structure and moderate to severe hyperaemia with colour Doppler or CEUS are correlated with a higher degree of inflammation in surgical specimen histology.23,24,30,53–56 The enhancement parameter most strongly correlated with the degree of inflammation is a higher peak in light intensity or a higher percentage of enhancement; and the one most strongly correlated with degree of fibrosis is some time until the elongated peak.23,24 The absence of signs of inflammatory activity in a stricture causing intestinal dilation suggests fibrosis.

Elastography is a new technique allowing tissue stiffness to be assessed using specific programmes included in ultrasound systems. A recent systematic review demonstrated a correlation between the degree of wall stiffness in the stricture measured by elastography and the histological grading of fibrosis.57

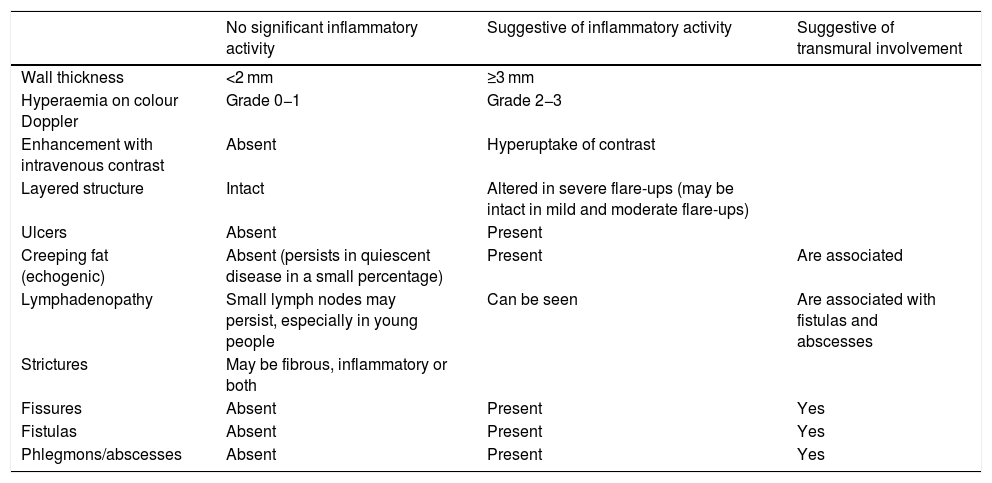

Inflammatory activityAssessment of inflammatory activity is important for planning and monitoring the effectiveness of medical treatment. The ultrasound parameters used to evaluate disease activity are shown in Table 1.

Ultrasound parameters of inflammatory activity in Crohn’s disease.

| No significant inflammatory activity | Suggestive of inflammatory activity | Suggestive of transmural involvement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall thickness | <2 mm | ≥3 mm | |

| Hyperaemia on colour Doppler | Grade 0−1 | Grade 2−3 | |

| Enhancement with intravenous contrast | Absent | Hyperuptake of contrast | |

| Layered structure | Intact | Altered in severe flare-ups (may be intact in mild and moderate flare-ups) | |

| Ulcers | Absent | Present | |

| Creeping fat (echogenic) | Absent (persists in quiescent disease in a small percentage) | Present | Are associated |

| Lymphadenopathy | Small lymph nodes may persist, especially in young people | Can be seen | Are associated with fistulas and abscesses |

| Strictures | May be fibrous, inflammatory or both | ||

| Fissures | Absent | Present | Yes |

| Fistulas | Absent | Present | Yes |

| Phlegmons/abscesses | Absent | Present | Yes |

Patient management in CD treatment has changed from simple management of symptoms to measurement of objective data on inflammatory activity, as clinical symptoms alone are neither sensitive nor specific for determining lesion severity in CD.

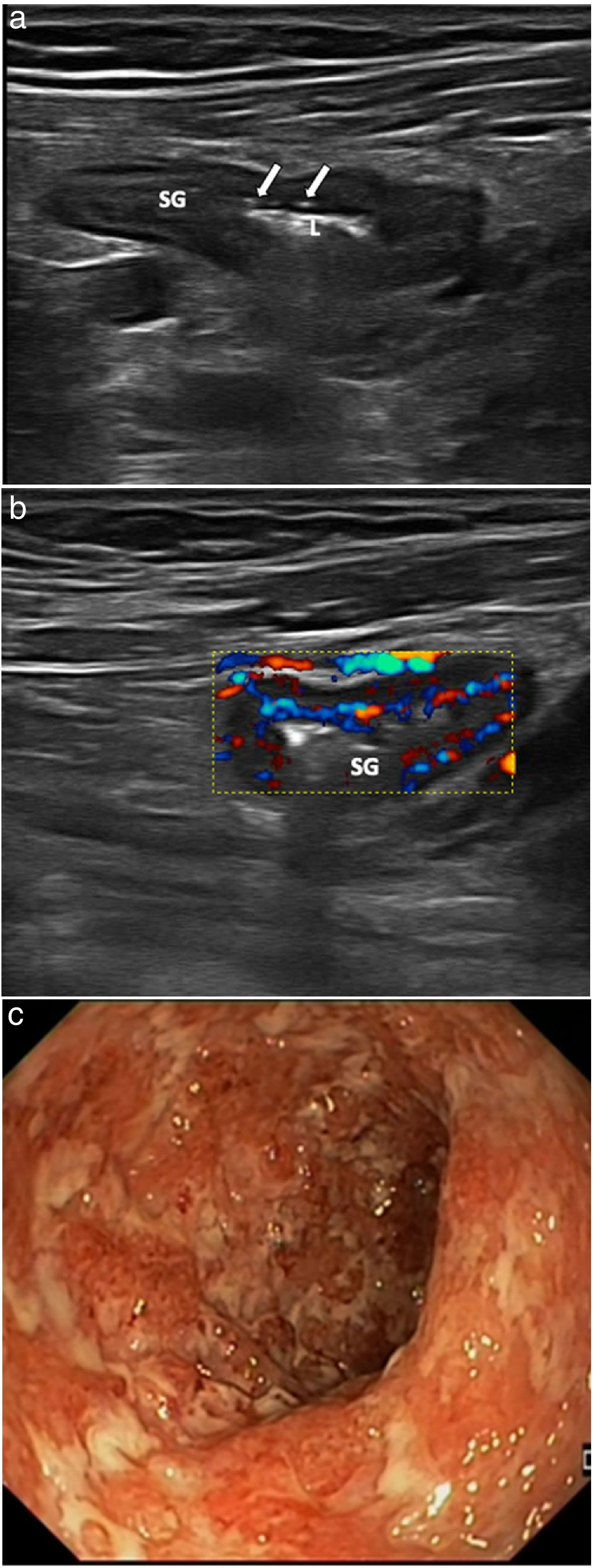

Evaluating the initial response (with ultrasound or MRI) is recommended within six months of starting treatment (Fig. 1).3 The main study showing the utility of ultrasound in monitoring CD is the TRUST study, a multicentre, prospective study in which 234 patients with activity were followed up for 12 months after starting treatment. Almost all parameters assessed (thickness, loss of stratification, creeping fat, Doppler signal, lymphadenopathy and stricturing) showed improvement after three months of treatment.40 Ultrasound changes for evaluating response may be apparent even earlier, having been reported on follow-up ultrasounds as early as two weeks32,58 or four weeks59 after starting treatment.

It has been suggested that assessment of treatment efficacy should be based on mucosal healing, with no ulcerations found in endoscopy, as this is associated with improved long-term outcomes.60 Normalisation of ultrasound parameters is closely correlated with mucosal healing in CD patients treated with biologic therapy (Fig. 9).61,62

Patient with asymptomatic Crohn’s disease being treated with immunosuppressants. a) Routine follow-up ultrasound confirms a thickening of the terminal ileum, presence of ulcers (arrow head) and focal loss of the layer structure (curved arrow). (FA and FV: femoral artery and femoral vein). b) The Doppler colour study shows grade 3 hyperaemia. With these findings, the patient was started on a TNF inhibitor (adalimumab). c) Ultrasound at 12 weeks after starting adalimumab shows a decrease in the thickness of the terminal ileum wall with normal wall vascularisation (grade 0). d) Follow-up at 12 months after starting treatment. Normalisation of findings, with normal wall thickness and absence of vascularisation (not shown). Terminal ileum (TI). Caecum (C).

Ultrasound findings also have prognostic value. Changes in ultrasound findings after starting treatment have been shown to be associated with medium- and long-term clinical outcomes in CD. A recent series including 51 patients with CD who began treatment with a TNF inhibitor showed that ultrasound changes at 12 weeks were able to predict the ultrasound response and clinical outcome at one year. In this study, clinical improvement at 52 weeks was significantly more common in patients who showed improvement in ultrasound parameters at week 12 than in those who did not (85% versus 28%; P < .0001). Complete disappearance of lesions (transmural healing) on ultrasound after one year of treatment is also associated with a lower likelihood of requiring a change in treatment or surgery within the following year.34,61

Ultrasound is as accurate as MRI in monitoring CD, as well as cheaper and more accessible. Comparison of ultrasound and MRI in diagnostic accuracy for assessing transmural healing has shown a high agreement between the two techniques (k = 0.90).63

Postoperative recurrenceThe incidence of recurrence after surgery in untreated CD is high (65%–90%). It typically appears at the anastomosis or neoterminal ileum.64. The severity of mucosal lesions is strongly associated with both clinical recurrence and prognosis, such that early detection requires significant changes in treatment or closer monitoring.63,64 The preferred technique for the initial assessment is ileocolonoscopy, preferably early, 6–12 months after surgery,64 using the Rutgeerts index (RI) to classify endoscopic lesions. However, it is not very clear when to perform the follow-up ileocolonoscopy; hence, the use of ultrasound in conjunction with calprotectin has been suggested as an alternative non-invasive method during follow-up of the disease.65

The overall sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound in detection of recurrence are 94% and 84%, respectively.66–68 Wall thickness is the main parameter studied and, in general, a thickness equal to or greater than 3 mm of the wall of the anastomosis or neoterminal ileum is considered a sign of recurrence. The use of oral contrast improves sensitivity, although specificity is reduced (sensitivity = 0.99 and specificity = 0.74).66 In addition, the baseline value that best predicts the presence of severe recurrence (RI ≥ 3) is a thickness of 5 mm or more, with sensitivity of 83.8% and specificity of 97.7%.69 Other signs associated with serious forms of disease are: presence of complications (fistulas, abscesses); proximal dilated stricture; echogenic creeping fat; colour Doppler hyperaemia; and wall enhancement with contrast.67–69

Ulcerative colitisThere are far fewer indications for ultrasound in ulcerative colitis (UC) than in CD for several reasons: a stronger correlation between the clinical signs and the endoscopic activity of the disease; a suitable correlation of endoscopic activity with faecal calprotectin70; and better accessibility to endoscopic assessment where there are validated endoscopic indexes.3 All of these factors explain why imaging tests are not required in the monitoring the response to UC treatment.71

According to the ECCO guidelines, systematic evaluation of the small intestine in patients with UC is not recommended; it is only considered in cases of diagnostic uncertainty in relation to CD, as in patients with rectal sparing, atypical symptoms or backwash ileitis.3 Ultrasound has shown a strong correlation with endoscopic findings in assessing the extent of the disease in a flare-up of UC. In patients in whom the disease begins with a severe flare-up and a limited endoscopic examination of the colon is performed due to the presence of severe lesions, or in whom proximal progression of the disease is suspected, ultrasound can determine the extent with a diagnostic reliability similar to that of colonoscopy.72,73

The most characteristic ultrasound findings are: symmetrical and continuous thickening of the intestinal wall, irregularity of the mucosal surface, submucosal oedema, loss of haustra and wall hyperaemia.73–75 The thickness for the diagnosis of UC is 3 mm in children73 and 4 mm in adults (Fig. 10), and there is a strong correlation between endoscopic activity and ultrasound findings;74,75 wall thickness and wall hyperaemia are the most useful parameters.72–75 As the disease is not transmural, mesenteric fat involvement and loss of bowel wall echotexture are less common,2 although they can be seen in severe flare-ups of the disease.45

Patient with severe flare-up of ulcerative colitis. Linear-array ultrasound transducer. a) Longitudinal plane of sigmoid colon (SG) with images of mucosal ulcers (arrows). Intestinal lumen (L). b) Colour Doppler ultrasound showing marked hyperaemia. c) Endoscopic correlation of the same patient with multiple deep ulcers, corresponding to severe endoscopic activity (Mayo score 3).

Ultrasound is an imaging technique that aids in diagnosis due to its immediacy. It also helps with monitoring IBD, especially CD, thus contributing to clinical decision-making. Ultrasound performs almost as well as MRI, but is cheaper, more accessible and better tolerated, and supplements endoscopy in managing the disease. However, widespread and established use of ultrasound in radiology departments and on IBD units is limited. Promotion of and training in the technique is therefore essential in order for ultrasound to be more generally incorporated into routine clinical practice.

In this era of awareness of the importance of avoiding radiation and reducing costs, we believe that, as recommended by the ECCO/ESGAR consensus, ultrasound, given its multiple advantages, should be considered a first-line test in assessing CD patients in all clinical situations (Table 2).

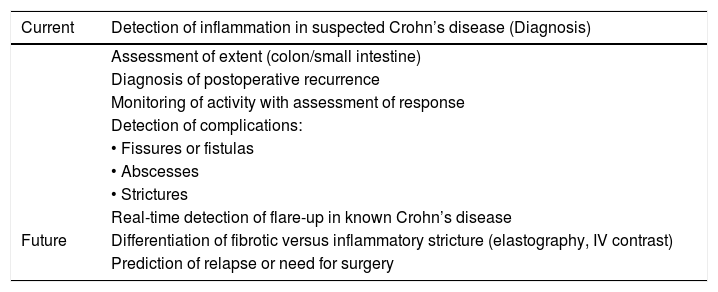

Indications for intestinal ultrasound in Crohn's disease.

| Current | Detection of inflammation in suspected Crohn’s disease (Diagnosis) |

|---|---|

| Assessment of extent (colon/small intestine) | |

| Diagnosis of postoperative recurrence | |

| Monitoring of activity with assessment of response | |

| Detection of complications: | |

| • Fissures or fistulas | |

| • Abscesses | |

| • Strictures | |

| Real-time detection of flare-up in known Crohn’s disease | |

| Future | Differentiation of fibrotic versus inflammatory stricture (elastography, IV contrast) |

| Prediction of relapse or need for surgery |

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ripollés T, Muñoz F, Martínez-Pérez MJ, de Miguel E, Poza Cordón J, de la Heras Páez de la Cadena B. Utilidad de la ecografía intestinal en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Radiología. 2021;63:89–102.