Stent thrombosis is the sudden occlusion of a stented coronary artery due to thrombus formation. Our objective was to identify variables associated to definite stent thrombosis (ST) and assess the outcomes of patients treated with bare-metal stents.

MethodsConsecutive patients treated between December 2007 and August 2012 were analyzed. Those with ST were compared to those without ST as to clinical and angiographic characteristics, and early and late outcomes.

ResultsOf a total of 6,495 percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs), 36 cases of ST (0.55%) were observed, of which 18 were early (50%), 14 (38.9%) late and 4 (11.1%) very late ST. Patients with ST were younger, with a greater prevalence of chronic renal failure and acute coronary syndromes. ST was more frequent in bifurcation lesions (11% vs. 4%; P=0.03) or lesions with visible thrombus at angiography (55.5% vs. 2.8%; P<0.01). All patients were submitted to emergency PCI, and in the inhospital phase, myocardial infarction (MI) and death were observed in 33.3% and 16.6%, respectively. Mean followup was 30.2+16.3months and early discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy was observed in 6 of the 36 cases (16.7%). In the late follow-up target vessel revascularization was observed in 33.3%, MI in 20% and no additional deaths were observed.

ConclusionsST proved to be an event with high in-hospital mortality and late morbidity. The occurrence of this event was associated to more complex clinical and angiographic characteristics and lower compliance with dual antiplatelet therapy.

Perfil Clínico e Evolução Tardia de Pacientescom Trombose de Stent Não-Farmacológico

IntroduçãoA trombose de stent é a oclusão súbita de uma artéria tratada com stent em decorrência da formação de trombos. Nosso objetivo foi identificar variáveis associadas à trombose definitiva de stent (TS) em stents não-farmacológicos e avaliar a evolução dos pacientes que apresentaram esse evento.

MétodosForam analisados pacientes tratados consecutivamente entre dezembro de 2007 e agosto de 2012. Aqueles com TS foram comparados ao grupo sem TS quanto às características clínicas e angiográficas, e evoluções inicial e tardia.

ResultadosDe um total de 6.495 intervenções coronárias percutâneas (ICPs), foram observados 36 (0,55%) casos de TS, sendo em 18 (50%) precoce, em 14 (38,9%) tardia e em 4 (11,1%) muito tardia. Pacientes com TS mostraram ser mais jovens, com maior prevalência de insuficiência renal crônica e síndrome coronária aguda. TS ocorrereu mais frequentemente em lesões de bifurcação (11% vs. 4%; P=0,03) ou lesões com presença de trombo visível à angiografia (55,5% vs. 2,8%; P<0,01). Todos os pacientes foram submetidos a ICP de emergência, sendo observados, na fase intra-hospitalar, infarto do miocárdio (IM) e óbito em 33,3% e 16,6%, respectivamente. O tempo médio de seguimento foi de 30,2±16,3 meses e a descontinuação precoce da terapia antiplaquetária dupla foi verificada em 6 dos 36 casos de TS (16,7%). Na evolução tardia observou-se revascularização do vaso-alvo em 33,3%, IM em 20% e nenhum óbito adicional.

ConclusõesA TS mostrou ser evento com elevada mortalidade hospitalar e alta morbidade tardia. A ocorrência desse evento foi associada a características clínicas e angiográficas de maior complexidade e a menor aderência à terapêutica antiagregante dupla.

Stent thrombosis (ST) is the sudden occlusion of an artery treated with a stent due to thrombus formation, which presents, in most patients, as sudden death (in approximately 20% to 40% of cases), myocardial infarction (MI) (in approximately 50% to 70%), or the need for revascularization.1-8

Despite the development of better stenting techniques, and more effective and more potent antiplatelet therapy, ST continues to occur in 1% to 2% of elective cases and in up to 5% of patients with acute coronary syndrome.3,6,9-12 Several observational studies have identified a number of clinical, angiographic, and procedure-related risk factors associated with the occurrence of ST, contributing to the identification of at-risk populations and the use of preventive measures against these events.3,6,9-11,13

As a result of myocardial ischemia caused by the sudden occlusion of an epicardial vessel by a thrombus, emergency revascularization by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the treatment of choice to restore vessel patency. Manual thrombus aspiration is an attractive option that is associated with higher rates of myocardial reperfusion. Emergency coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is required in a minority of cases (<10%) when recanalization of the occluded vessel cannot be achieved.1

The present study aimed to identify the clinical and angiographic variables and to assess the late evolution of patients with ST treated at a tertiary hospital in the public healthcare network of the state of São Paulo.

METHODSStudy design and populationA retrospective data analysis was performed of patients treated in the Invasive Cardiology Department of Instituto Dante Pazzanese de Cardiologia (São Paulo, SP, Brazil) from December 2007 to August 2012. During this period, the clinical and angiographic data, as well as those related to procedural and in-hospital evolution were prospectively collected and stored in a dedicated electronic database, according to a pre-established protocol, for all patients undergoing elective or emergency PCI.

The present study included all patients that were treated at this institution for ST with bare-metal stents (BMS), and compared their clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics with the characteristics of cases without ST. Patients treated with drug-eluting stents (DES) were excluded, as they represented a minority of this population, and because they comprised part of research protocols that did not always include PCI in everyday clinical practice, which was the aim of this analysis.

DefinitionsST is defined, according to the Academic Research Consortium (ARC),1 as the angiographic confirmation of the presence of a thrombus that originated inside the stent or in the segment surrounding the 5mm proximal or distal to the stent, and that was associated with at least one of the following criteria within a 48-hour time window: acute ischemic symptoms at rest; new ischemic alterations on ECG; typical increases and decreases in markers of myocardial necrosis; and the presence of an occluding or non-occluding thrombus. ST was also defined through the pathological confirmation of a recent thrombus within the stent during autopsy or through the analysis of tissue removed during thrombectomy.

ST was also classified according to the time of occurrence after stent implantation, as acute (24hours), subacute (> 24 hours to 30 days), late (> 30 days to one year), or very late (> one year). The acute and subacute cases of ST were grouped together as early stent thrombosis.1

Periprocedural MI was defined by an increase in the biomarker creatine phosphokinase MB-fraction of>three times the normal upper limit in a test performed at 48 hours post-procedure.1 Major adverse clinical events (MACEs) were defined by the combined outcomes of death from any cause, MI, and emergency heart surgery. Angiographic success was defined by the achievement of Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade 3, absence of a thrombus, dissection or perforation with active extravasation of contrast material, and residual stenosis<20% (quantitative coronary angiography) in the treated segment at the end of the procedure. Procedural success was defined as angiographic success, together with the absence of MACEs during the index hospitalization.

The diagnosis of renal failure was established in patients with creatinine clearance<60mL/min/1.73m2.

ProcedureThe PCI procedures were performed according to the current guidelines, aiming for optimal angiographic results after coronary device implantation.14 The choices of arterial access route, the material used in the PCI (guidewire and balloon catheter, among others), the type of stent used, the stent implantation technique, and the adjunctive medical therapy were at the surgeon’s discretion. Regarding antithrombotic therapy, the pre-treatment included acetylsalicylic acid, at a dose of 100mg/day in cases of chronic use (>seven days) or at a loading dose of 200mg administered>24 hours prior to PCI, and clopidogrel, at a loading dose of 300mg>24 hours before the intervention or 600mg before the procedure (preferably>two hours) in patients with acute coronary syndrome. After the procedures, the patients were instructed to maintain dual antiplatelet therapy (acetylsalicylic acid 100mg and clopidogrel 75mg) for at least one month in cases of BMS placement, and for one year for DES. Regarding antithrombin therapy during the procedure, heparin was administered intravenously at a dose of 70 U/kg to 100 U/kg of body weight to maintain activated clotting time>250 seconds, or>200 seconds in cases of concomitant administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, prescribed at the surgeon’s discretion.

Complementary examinations were conducted according to the institutional protocol, and they included 12-lead electrocardiography before, immediately after and once daily after the procedure until hospital discharge. The laboratory tests included analysis of cardiac biomarkers pre-procedure, at the first 24 hours post-procedure, and once daily until hospital discharge.

Angiographic analysisQualitative and quantitative angiographic analyses were performed before and after the procedures. A qualitative assessment was performed in accordance with the criteria used for American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) classification.15 Lesions were considered as type C when they had at least one of the following characteristics: extension>20mm (diffuse injury); significant tortuosity (three or more angles>75° in the segment proximal to the lesion); significant lesion angulation (>90°); bifurcation lesions with the inability to protect the side branch with a guidewire; degenerated saphenous vein graft lesions; and chronic occlusion (>three months). The analysis of quantitative coronary angiography was performed offline by experienced professionals, using validated and commercially available software (QAngio XA, release 7.3 – Medis Medical Imaging Systems BV – Leiden, the Netherlands). Lesion extent was defined by the distance between points immediately before and after the target stenosis was considered as free of atheromatous disease, that is, the transition between the stenotic segment and the normal reference. The minimal luminal diameter (MLD) and the reference vessel diameter (RVD) were used to calculate the stenosis diameter (SD) using the following formula: SD (%)=(1 – [MLD/RVD])×100. Immediate gain was defined as the pre- and post-procedure difference in MLD (post-procedure MLD – pre-procedural MLD). Quantitative variables were reported in the intrastent and intra-segment segments, which included the intrastent segment combined with the 5-mm borders in the peristent regions, according to the previously described methodology.

Statistical analysisFor comparative purposes, the total population was divided into two groups, according to the presence or absence of thrombosis, aiming to identify factors associated with this adverse event. Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages and were compared by the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The quantitative variables are expressed as the means and standard deviations and were compared using Student’s t-test. A p-value<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTSOf the total of 6,495 PCIs with BMS performed during the study period, there were 36 (0.55%) cases of ST, with 18 (50%) early (acute or subacute), 14 (38.9%) late, and four (11.1%) very late events.

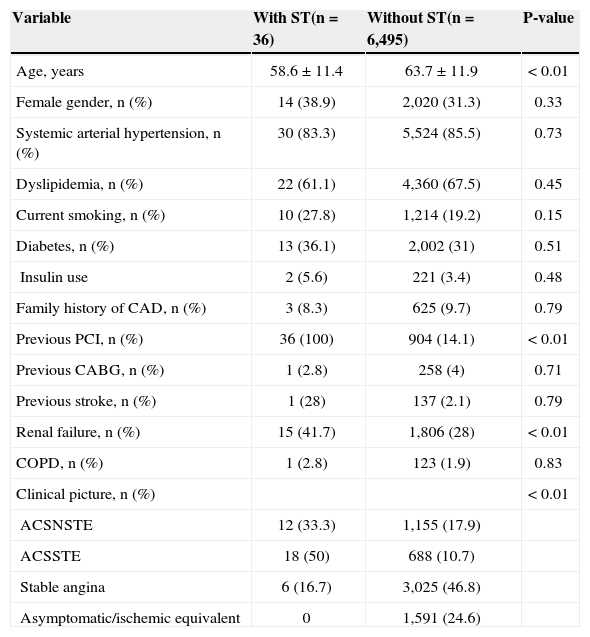

Patients with ST were younger (58.6±11.4years old vs. 63.7±11.9years old; P<0.01) and had a higher prevalence of previous PCI (100% vs. 14.1%; P<0.01), chronic renal failure (41.7% vs. 28%; P<0.01), and procedures performed in the presence of acute coronary syndrome when compared to patients without ST. There were no differences between the groups regarding gender, comorbidities, or the prevalence of risk factors for atherosclerosis (Table 1).

Basal clinical characteristics

| Variable | With ST(n=36) | Without ST(n=6,495) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 58.6±11.4 | 63.7±11.9 | < 0.01 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 14 (38.9) | 2,020 (31.3) | 0.33 |

| Systemic arterial hypertension, n (%) | 30 (83.3) | 5,524 (85.5) | 0.73 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 22 (61.1) | 4,360 (67.5) | 0.45 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 10 (27.8) | 1,214 (19.2) | 0.15 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 13 (36.1) | 2,002 (31) | 0.51 |

| Insulin use | 2 (5.6) | 221 (3.4) | 0.48 |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 3 (8.3) | 625 (9.7) | 0.79 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 36 (100) | 904 (14.1) | < 0.01 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 1 (2.8) | 258 (4) | 0.71 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 1 (28) | 137 (2.1) | 0.79 |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 15 (41.7) | 1,806 (28) | < 0.01 |

| COPD, n (%) | 1 (2.8) | 123 (1.9) | 0.83 |

| Clinical picture, n (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| ACSNSTE | 12 (33.3) | 1,155 (17.9) | |

| ACSSTE | 18 (50) | 688 (10.7) | |

| Stable angina | 6 (16.7) | 3,025 (46.8) | |

| Asymptomatic/ischemic equivalent | 0 | 1,591 (24.6) |

ST, stent thrombosis; CAD, coronary artery disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ACSSTE, acute coronary syndrome with ST-segment elevation; ACSNSTE, acute coronary syndrome without ST-segment elevation.

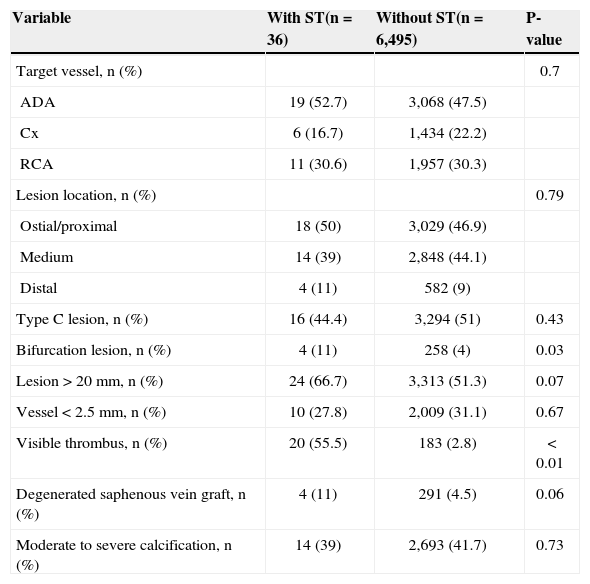

ST occurred more frequently in bifurcation lesions (11% vs. 4%; P=0.03) and in lesions with visible thrombi on angiography (55.5% vs. 2.8%; P<0.01) (Table 2). ST also tended to occur more often in lesions located in degenerated saphenous vein grafts (11% vs. 4.5%; P=0.06) and in lesions>20mm (66.7% vs. 51.3%; P=0.07).

Angiographic characteristics

| Variable | With ST(n=36) | Without ST(n=6,495) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target vessel, n (%) | 0.7 | ||

| ADA | 19 (52.7) | 3,068 (47.5) | |

| Cx | 6 (16.7) | 1,434 (22.2) | |

| RCA | 11 (30.6) | 1,957 (30.3) | |

| Lesion location, n (%) | 0.79 | ||

| Ostial/proximal | 18 (50) | 3,029 (46.9) | |

| Medium | 14 (39) | 2,848 (44.1) | |

| Distal | 4 (11) | 582 (9) | |

| Type C lesion, n (%) | 16 (44.4) | 3,294 (51) | 0.43 |

| Bifurcation lesion, n (%) | 4 (11) | 258 (4) | 0.03 |

| Lesion>20mm, n (%) | 24 (66.7) | 3,313 (51.3) | 0.07 |

| Vessel<2.5mm, n (%) | 10 (27.8) | 2,009 (31.1) | 0.67 |

| Visible thrombus, n (%) | 20 (55.5) | 183 (2.8) | < 0.01 |

| Degenerated saphenous vein graft, n (%) | 4 (11) | 291 (4.5) | 0.06 |

| Moderate to severe calcification, n (%) | 14 (39) | 2,693 (41.7) | 0.73 |

ST, stent thrombosis; ADA, anterior descending artery; Cx, circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

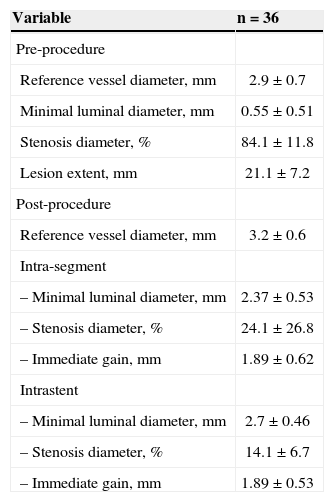

Table 3 presents the results of the quantitative coronary angiography analysis of patients with ST.

Quantitative coronary angiography of cases with coronary stent thrombosis

| Variable | n =36 |

|---|---|

| Pre-procedure | |

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | 2.9±0.7 |

| Minimal luminal diameter, mm | 0.55±0.51 |

| Stenosis diameter, % | 84.1±11.8 |

| Lesion extent, mm | 21.1±7.2 |

| Post-procedure | |

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | 3.2 ± 0.6 |

| Intra-segment | |

| – Minimal luminal diameter, mm | 2.37±0.53 |

| – Stenosis diameter, % | 24.1±26.8 |

| – Immediate gain, mm | 1.89±0.62 |

| Intrastent | |

| – Minimal luminal diameter, mm | 2.7±0.46 |

| – Stenosis diameter, % | 14.1±6.7 |

| – Immediate gain, mm | 1.89±0.53 |

Among the patients with ST, the mean clinical follow-up duration was 30.2±16.3months. Early discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy (< one month for BMS) was observed in six of the 36 cases of ST (16.7%).

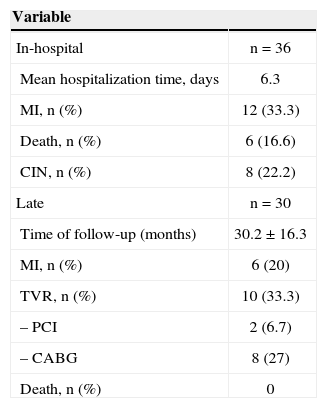

All patients were submitted to emergency PCI; during the in-hospital phase, the incidences observed of periprocedural myocardial infarction, contrast-induced nephropathy and death were 33.3%, 22.2% and 16.6% of cases, respectively (Table 4). During the late follow-up period, target-vessel revascularization was observed in 33.3% of cases, which was achieved by CABG in most cases. A new MI was observed in six (20%) cases, two resulting from recurrent ST. No additional deaths were observed.

In-hospital and late clinical follow-up of cases with coronary stent thrombosis

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| In-hospital | n=36 |

| Mean hospitalization time, days | 6.3 |

| MI, n (%) | 12 (33.3) |

| Death, n (%) | 6 (16.6) |

| CIN, n (%) | 8 (22.2) |

| Late | n=30 |

| Time of follow-up (months) | 30.2±16.3 |

| MI, n (%) | 6 (20) |

| TVR, n (%) | 10 (33.3) |

| – PCI | 2 (6.7) |

| – CABG | 8 (27) |

| Death, n (%) | 0 |

MI, myocardial infarction; CIN, contrast-induced nephropathy; TVR, target vessel revascularization; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft.

The main findings of the present study were: ST after BMS implantation occurred in the late phase (>30days) in 50% of cases; early discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy was observed in one-sixth of patients with ST; the presence of renal failure, bifurcation lesions, or evident thrombus on angiography, and of long lesions or of lesions located in degenerated saphenous vein grafts was more frequent in patients with ST; and in-hospital mortality in this population was high (16.7%), as was the incidence of new MACEs during the late clinical follow-up period.

Historically, ST in BMS has been an event that occurs more frequently during the initial days after surgery, and, by definition, has not been reported after the first month. The first reports of late ST with BMS appeared only after the recognition of late thrombosis with brachytherapy.16,17 Wenaweser et al.17 demonstrated, in one of the largest series of patients treated with BMS, that ST occurred in 1.6% of cases; it was acute in 11%, subacute in 64%, and late in 25% of patients.

ST is a complex phenomenon, and its etiology is multifactorial. According to some studies,3,13,18,19 early discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy (<one month for BMS) is one of the most important factors associated with ST. lakovou et al.3 demonstrated, in patients treated with drug-eluting stents, that the most important independent predictor of ST was the premature discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy (hazard ratio [HR]=89.78; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]=29.9 to 269.6), followed by renal failure (HR 6.49; 95% CI=2.6 to 16.15), bifurcation lesions (HR 6.42; 95% CI=2.93 to 14.07), diabetes (HR 3.71, 95% CI=1.74 to 7.89), and ejection fraction (HR 1.09; 95% CI=1.05 to 1.36 for every 10% reduction).

Renal failure is associated with increased mortality, despite a successful PCI.20-22 Renal failure is associated with metabolic and microcirculatory abnormalities, which can predispose the patient to thrombus formation.23,24 Regarding bifurcation lesions, histopathology studies have suggested that the locations of arterial branching have low shear regions and low speed flow, predisposing the vessels to the development of atherosclerotic plaques and thrombi.25-27

Study limitationsThe limitations of the present study include the retrospective analysis of the data from two cohorts with non-adjusted clinical variables and the performance of the study in a single centre. Additionally, only individuals with ST treated at this institution were included, which may have resulted in the underestimation of the true incidence.

CONCLUSIONSIn this contemporary real-world experience, ST was shown to be an event with high rates of hospital mortality and late morbidity. As demonstrated by other studies, the occurrence of this event was associated with clinical and angiographic characteristics of greater complexity, and with lower adherence to the prescribed antiplatelet therapy.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.