Inborn errors of metabolism are alterations in one or more steps in a metabolic pathway. They are associated with multisystem complications and have a high impact on the quality of life of patients. Enzyme replacement has extended life, hence the importance of recognizing the most frequent anesthetic complications.

ObjectiveTo describe the complications of anesthetic management in pediatric patients with inborn errors of metabolism undergoing non-cardiac surgery.

MethodsRetrospective descriptive observational case series of pediatric patients with inborn errors of metabolism undergoing non-cardiac surgery at the Pablo Tobón Uribe Hospital between 2008 and 2011, and their anesthetic outcomes.

ResultsThe most frequent inborn error of metabolism was glycogen storage disease type III in 7 (37%), followed by nonketotic hyperglycinemia in 4 (21%). There were 2 (6%) anesthetic complications in the immediate post-operative period in patients with nonketotic hyperglycinemia, with seizures in one case and the need for mechanical ventilation in another.

ConclusionsLow-risk procedures probably explain why there were few complications. It was found that seizures and respiratory insufficiency are potential perioperative complications in nonketotic hyperglycinemia.

los errores innatos del metabolismo son alteraciones en uno o varios pasos de alguna vía metabólica que se asocian a complicaciones multisistémicas y tienen alto impacto en la calidad de vida de los pacientes. El reemplazo enzimático ha prolongado la vida, por lo que se hace importante reconocer las complicaciones anestésicas más frecuentes.

Objetivodescribir las complicaciones del manejo anestésico en pacientes pediátricos con errores innatos del metabolismo sometidos a cirugía no cardiaca.

Métodosestudio observacional descriptivo retrospectivo, tipo serie de casos, de pacientes pediátricos con errores innatos del metabolismo sometidos a cirugía no cardiaca en el Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe entre 2008 y 2011 y sus desenlaces anestésicos.

Resultadosel error innato del metabolismo más frecuente fue la glucogenosis tipo iii en7 (37%), seguido de la hiperglicinemia no cetósica en 4 (21%). Se presentaron 2 (6%) complicaciones anestésicas en el postoperatorio inmediato de pacientes con hiperglicinemiano cetósica con convulsiones en un caso y necesidad de ventilación mecánica en otro.

Conclusioneslos procedimientos de bajo riesgo probablemente explican las pocas complicaciones presentadas. Se observó que las convulsiones y la insuficiencia respiratoria sonposibles complicaciones perioperatorias en la hiperglicinemia no cetósica.

Inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) are biochemical disorders due to a defective protein involved in a metabolic pathway. They are associated with multisystem complications in pediatric patients1,2 and may cause of premature death, severe neurologic disorders, mental retardation and poor quality of life.2

Reported incidences of IEMs range from 1:800 to 1:5000 births2 and are usually underdiagnosed due to non-specific symptomatology, low index of suspicion, intermittent manifestation of some disorders1 and a broad spectrum of presentations due to enzyme activity levels influencing the presentation of the disease.2

Enzyme replacement therapy and a better understanding of the pathophysiology have extended life expectancy in these patients,2 which means that they are taken more frequently to non-cardiac surgery in multi-disciplinary hospitals. Only case reports are found in the literature about anesthetic management in some type of specific disorder, but there are no studies including IEMs in general.3–5 Hence the importance of describing the behavior and perioperative complications in these patients.

Materials and methodsRetrospective descriptive observational case series at the Pablo Tobón Uribe Hospital (HPTU). A search was conducted in the database of the Clinical Record Management Department of the electronic records of pediatric patients under 15 years of age with IEM who underwent non-cardiac surgery and required anesthesia or sedation between 2008 and 2011, based on the International Nursing Code version 10 (INC 10). The study was approved by the HPTU Research and Ethics Committee as stated in minutes No. 02-2012 of February 2012. The confidentiality of the reviewed clinical records was preserved.

Data collection in Excel included demographic and clinical variables, procedures performed, monitoring used, intra- and immediate post-operative incidents and complications. The anesthetic technique was not standardized. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA); absolute and relative frequency measurements were described for qualitative variables, and means with standard deviations (SD) were measured for continuous variables.

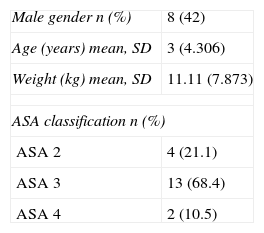

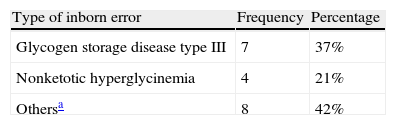

ResultsIn total, 19 patients were included, some of whom required more than one intervention under sedation or general anesthesia for diagnostic and/or therapeutic procedures, totaling 34 events. Table 1 describes the clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients. Table 2 shows specific IEM diagnoses.

Specific diagnoses of inborn errors of metabolism.

| Type of inborn error | Frequency | Percentage |

| Glycogen storage disease type III | 7 | 37% |

| Nonketotic hyperglycinemia | 4 | 21% |

| Othersa | 8 | 42% |

Source: Authors.

Glycogen storage disease tipo XI and Fanconi's syndrome, Pompe's syndrome (glycogen storage disease type II), 3-hydroxy methyl glutaric aciduria, propionic aciduria, hyperammonemia without metabolic acidosis, hyperammonemia and carnitine deficit, ornitine transcarbamylase deficit, mucopolysaccharidosis.

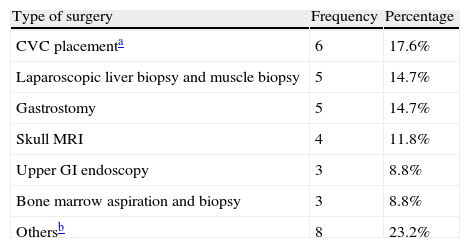

All patients were scheduled for elective surgery (Table 3), 13 (38%) had maintenance metabolic flow at the time they entered surgery, and a difficult venous access was reported in 11 (32.4%).

Basic monitoring was used in all cases. Inhalation induction with sevoflurane was used in 25 cases (73.5%), intravenous induction with propofol was used in 6 (18%) and ketamine was used in 1 (3%). Dexamethasone for nausea and vomiting prophylaxis was used in 4 cases (12%). Airway management was done with orotracheal intubation in 21 (61.8%) cases.

Mean anesthesia time was 70min (SD 54.836). Twenty-six patients (76%) were transferred to a general unit, 4 (12%) were transferred to the Special Care Unit (SCU) and 4 (12%) were taken to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

There were 7 patients with glycogen storage disease type III and 4 were taken to liver biopsy. The preoperative echocardiographic assessment showed that 4 had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and there was association with pericardial disease in 2 cases. None of these patients had anesthetic complications and they were all transferred to the genera recovery room.

There were 4 patients with nonketotic hyperglycinemia (NKHG). A 13-day old baby, admitted to the general room with hyperammonemia and left ventricular hypertrophy was scheduled for central venous catheter (CVC) placement, with no complications. At 6 months of age she was taken to bone marrow aspiration and biopsy and presented tonic seizures in the immediate postoperative period. She was treated with rectal diazepam and temporary intubation, and had a difficult intravenous access that required placement of a CVC. Metabolic acidosis, hyperglycemia and anemia were documented, and the course was favorable.

Another one-month old patient with a diagnosis of NKHG was scheduled for gastrostomy and admitted to the ICU with the use of continuous nasal positive pressure and recent invasive mechanical ventilation. The patient was intubated for the procedure, and induction and maintenance were achieved only with sevoflurane. The patient required post-operative mechanical ventilation because of insufficient ventilatory drive, with a normal chest X-ray and blood gases showing metabolic alkalosis. He was extubated the next day without complications. At 5 months of age, he was scheduled for ventriculo-peritoneal shunting and CVC, with transient intraoperative hypotension, and later for CVC, and high-resolution chest CT scan, with no anesthetic complications.

A 12 year-old patient with mucopolysaccharidosis and a history of drug hepatotoxicity but no alteration in coagulation tests and a preoperative platelet count of 108,000mm3 was taken to laparoscopic cholecystectomy that was converted to an open procedure due to significant intraoperative bleeding. The patient required red blood cell transfusion and postoperative management in the SCU.

There were no cases of difficult airways, arrhythmias, desaturation episodes, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, nausea, vomiting or cardiac arrest.

DiscussionApproximately 550 IEMs exist, the majority of which go undiagnosed6; however, their cumulative incidence is 2% in the entire population.6

In this case series, the most frequent IEM was glycogen storage disease type III, although in the literature the most frequent are acetyl Co-A dehydrogenase deficiency and fenylketonuria.2

The few complications are probably due to a small sample of patients scheduled for diagnostic procedures or low-risk elective surgery, with preoperative optimization.

In the preanesthetic assessment it is important to examine for cardiorespiratory compromise and airway alterations, in particular in mucopolysaccharidoses, because those patients may have cervical spine instability.2,4,7 Preoperative laboratory testing must be individualized according to the patient's involvement.2–5 It is striking that four out of the seven patients with glycogen storage disease type III were diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, when the usual thing is for them to present liver and muscle involvement.

Two of the three anesthetic complications occurred in patients with NKHG: seizures in the immediate postoperative period in once case and the need for mechanical ventilation in another, possibly secondary to the clinical characteristics of these patients such as respiratory insufficiency, generalized hypotonia, poor sucking ability, and seizures that are difficult to control.8 Factors prolonging recovery from anesthesia include premedication, muscle relaxants, opioids and hypothermia.9

These patients require close monitoring during the postoperative period because of the risk of metabolic decompensation and clinical deterioration, and pharmacological and dietary management must be resumed early on.2

Elective surgeries must always be performed in centers where a multidisciplinary team and ICU are available.2 Prolonged fasting periods must be avoided, fluids with dextrose must be administered, and adequate hydration is critical in order to avoid metabolic decompensation.2

The limitations of this retrospective study include underecording, poor classification of diagnostic entries in the INC-10 and incomplete data in some clinical records.

Patients with IEM are frequently scheduled for anesthetic procedure. There is still very little knowledge among specialists in Colombia about this type of patients,10 resulting in the need for clear protocols for preanesthetic optimization and perioperative management plans in order to provide the best care to these patients.

FundingHospital Pablo Tobón Uribe and the authors own resources.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

In the Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe, to the doctor Carlos Enrique Yepes Delgado, PhD in Epidemiology.

Please cite this article as: Berrío Valencia MI, et al. Complicaciones anestésicas en pacientes con errores innatos del metabolismo sometidos a cirugía no cardiaca. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2013;41:257–260.