Critical intraoperative events are rare and may sometimes be managed poorly and too late.

ObjectiveTo translate and update the checklists developed by Ariadne Labs for management of critical events in the OR and to adapt the list for managing anesthetic toxicity, based on secondary clinical evidence.

Materials and methodsIn order to translate and update the checklists, the recommendations given by Ariadne Labs were followed to change the original checklists in accordance with a systematic methodology that comprises three phases: (1) translation of the original lists, (2) systematic literature search, (3) evaluation and selection of evidence, (4) adaptation of the list for managing anesthetic toxicity, (5) changes, deletions, and additions to the translated lists, and (6) layout of the checklists.

ResultsThe 12 original checklists were translated into Spanish and a new list was adapted for managing toxicity from local anesthetic agents. As a result of the systematic literature search, 1407 references were screened, from which 7 articles were selected and included for evidence-based updating of the new checklists. The layout of the new lists was consistent with the design recommendations of the original lists.

Conclusion12 translated and updated checklists were submitted and a new list was adapted for the management of local anesthetics toxicity, based on a systematic literature review.

Los eventos críticos intraoperatorios son situaciones raras y su manejo en ocasiones podría ser inoportuno e inadecuado.

ObjetivoTraducir y actualizar las listas de chequeo para manejo de eventos críticos en salas de cirugía desarrolladas por Ariadne Labs y adaptar la lista para el manejo de la toxicidad por anestésicos locales, a partir de evidencia clínica secundaria.

Materiales y métodosPara la traducción y actualización de las listas de chequeo se siguieron las recomendaciones de Ariadne Labs para la modificación de las lista de chequeo originales de acuerdo a una metodología sistemática dividida en fases: 1) traducción de las listas originales, 2) búsqueda sistemática de la literatura, 3) evaluación y selección de la evidencia, 4) adaptación de la lista para manejo de toxicidad por anestésicos locales, 5) cambios, sustracciones y adiciones a las listas traducidas, y 6) diagramación de las listas de chequeo.

ResultadosSe tradujeron al español las 12 listas de chequeo originales y se adaptó una nueva lista para el manejo de toxicidad por anestésicos locales. Como resultado de la búsqueda sistemática de la literatura se tamizaron 1.407 referencias, de las cuales se seleccionaron e incluyeron 7 artículos con los que se actualizaron las nuevas listas de chequeo con base en la evidencia. Las nuevas listas se diagramaron según las recomendaciones de diseño de las listas originales.

ConclusiónSe presentan 12 listas de chequeo traducidas y actualizadas y se adaptó una nueva para el manejo de toxicidad por anestésicos locales. Todo ello a partir de una revisión sistemática de la literatura.

Critical events in operating rooms are rare occurrences, but they can be stressing and potentially fatal, requiring timely, rapid and coordinated management for successful outcomes.1–3 Under these circumstances, the response of the healthcare team may be crucial for patient survival.2 Some observational studies on critical events requiring advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS), have shown that the compliance of the healthcare staff with the clinical management guidelines is poor and that in some cases the performance of the healthcare team fails to be timely and adequate.4 It has also been shown that after ACLS training, the health staff fails to recall most of the knowledge imparted.5–8

It has been estimated that the incidence of critical intraoperative events is 145 per every 100,000 surgeries.9 Considering that around 313 million surgical procedures are done every year around the world,10 and that by 2012 more than 5 million surgeries were performed annually in Colombia,11 it may be estimated that there are around 8 thousand critical intraoperative events per year in our country. However, from an individual perspective and considering the number of people involved in the care of surgical patients, the occurrence of an intraoperative critical event is relatively rare.12

The results of some trials have suggested that one of the main causes for the variation in surgical mortality among hospitals is the inability to properly manage critical intraoperative events and other potentially fatal complications.13–15

Cognitive aids are memory prompts containing important information presented in an analog or digital format that serve as a reminder of diagnostic and corrective instructions for managing special situations.16 Cognitive aids are tools that assist in decision making since they are not just learning aids.17,18 Cognitive aids may be presented as algorithms, acronyms, and checklists, inter alia.19 Checklists are widely accepted in other high-risk settings (aviation and nuclear plants) as a tool to help improve performance during critical, rare and unpredictable events.20 Several of these cognitive aids have been described in the literature for managing critical events in the OR.1,21–24 A collection of cognitive aids or checklists is called an emergency manual.17

The use of cognitive aids in the management of critical events has been correlated with improved compliance with the clinical management guidelines.16,25 Evidence suggests that checklists have a favorable impact on the coordination, communication, and overall performance of clinical teams and that their lineal design could offer some advantages versus the branched design of algorithms.26 In anesthesiology, the use of the checklist for surgical safety during routine perioperative care has been associated with a significant decrease in morbidity and mortality.27,28 Consequently, with this evidence, checklists have quickly become a standard of care in perioperative medicine.29–32

In 2011 Ziewacz et al., developed and initially tested in high-fidelity simulated surgical settings some checklists for managing critical events in the OR. The actions (recommendations) described in the checklists were initially developed based on an extended literature search including 48 articles that defined the potentially lethal critical events in the OR and the corresponding evidence-based clinical management was established.1 The lists were then subject to a process of effectiveness evaluation by the same developer group. The effectiveness of checklists to improve compliance with management guidelines and the perception of the healthcare staff about the usefulness and clinical relevance of these cognitive aids was evaluated in a controlled randomized trial in simulated surgical environments.2 The trial showed that when checklists are available, non-compliance with vital processes established under the clinical management guidelines is considerably reduced (adjusted relative risk, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.18–0.42; P value <0.001), and that 97% of the staff involved in perioperative management would use the checklists in the occurrence of an actual critical intraoperative event.2

Up to now, no formal checklists (neither other cognitive aids) have been formally established in Spanish for the management of critical events in the OR, adapted to the Colombian environment. Hence, the purpose of this initiative was to update the checklists developed by Ariadne Labs (Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard School of Public Health)33 for managing critical events in the OR and to adapt the list for the management of local anesthetic toxicity, based on secondary clinical evidence.

MethodsThis project was possible thanks to the initiative and sponsorship of the Colombian Society of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation (S.C.A.R.E.). A group of methodology experts (with their respective support staff) and clinical experts was organized to advance the project. Every project team member was required to complete a form stating any conflicts of interest. Then a phased methodology was used. Each phase followed standard procedures to develop evidence-based secondary evidence.34

Generally speaking, Ariadne Labs recommendations were followed for making changes to the original checklists33:

Any additional impact on the applicability of the list was carefully evaluated, maintaining a balance between content and complexity.

Short, direct and unequivocal sentences were used, that were easy to read aloud. The number of actions was limited to exclusively the most important ones, following the conventions of color, typographic, and layout. The font shall be as large as possible, consistent with the style established.

No text or color tabs were added.

Considering that tables, arrows and other graphics further complicate the visualization of the checklist, these were only used if strictly necessary to avoid ambiguity of the actions. Light colors were used to minimize any distraction.

Blank spaces were preserved as much as possible.

Translation of the original checklistsAriadne Labs granted written permission to translate and make changes to the original checklists. The original checklists in English were used, extracting the various components into plain text: (1) list identification and description, (2) actions, and (3) information on references. Two of the authors were responsible for translating the complete original lists, with particular emphasis on adapting the language to the Colombian setting and changing any ambiguous terms and sentences. Any medications not available in Colombia were removed, while others that are commonly used in the country were added. The resulting initial translation was primarily validated by an expert on each list's topic and finally by all the team members in the project via non-formal consensus.

Systematic literature searchFor the design of the search strategies a generic question was asked that could be answered on the basis of clinical evidence. The question was: which are the most effective and safe interventions for managing any critical events arising in the OR? This question was asked for each checklist in order to design a search strategy in electronic data bases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and LILACS) using the terms MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), Emtree (EMBASE tree), DeCS (Health Sciences Descriptors), text terms, Boolean operators (AND, OR) adaptable to the various data bases. The validated filters were introduced to identify any systematic reviews to answer the question asked.

In addition to the electronic database, other gray literature searches were done, manual search of specialized journals and contacts with experts. Furthermore, the snow-ball search strategy was used based on the list of references in each publication selected and the Google scholar citation function.

The process complied with the quality standards used in systematic literature reviews and met the requirements and strategies listed in the methodological guidelines. The systematic database search was lead by the Cochrane Review Group STI from the Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Evidence Evaluation and SelectionUpon selecting the final electronic searches as well as other sources of information, a selection of the relevant literature for each checklist was undertaken. At least two reviewers reviewed the titles and abstracts. Any disagreements regarding the inclusion or exclusion of references were solved by consensus. After selecting the articles included, the complete texts were obtained. Two independent authors completed the quality evaluation and data collection. At this stage, any disagreements were settled through third-party reviewer arbitration.

Development of checklist for managing local anesthetic toxicityTo develop the checklist for managing systemic toxicity resulting from local anesthetic agents, two background documents were used: the safety guideless of the Association of Anesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland – AAGBI,35 and the checklist of the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine – ASRA.23 A written authorization was obtained for the translation and amendment of these tools.

One of the authors transcribed all the relevant elements for the original lists and then translated the original text into Spanish, emphasizing the importance of adapting the terminology to the Colombian setting and changing any ambiguous terms and sentences. The result of the initial translation was initially validated by a clinical expert, and lastly by all of the authors participating in the project. Any disagreements were solved by consensus.

Changes, deletions and additions to the translated listsAfter a critical reading of the literature, changes, deletions and additions to the checklists translated into Spanish were drafted. All changes were done to the checklists in plain text. Any changes were initially approved by the expert on the topic of the checklist. All of the final items in the checklists were discussed and approved by all the experts on the various topics and methodologies.

Checklist layoutTwo authors were responsible for the layout of the translated and updated checklists. This process was completed using Adobe InDesign CC® (2016, Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA, EUA) with the original templates designed by Ariadne Labs. The result of the layout was approved by all the authors.

Drafting of the final documentThe document reflects the context, the methodology, and the results of the translation initiative and update of the checklists, incorporating and reconciling the recommendations with the expert consensus. The written document was submitted for publication upon approval of all the team members and shall be endorsed by the center for technological development of S.C.A.R.E.

Peer review and publicationThe final document was submitted for review by two academic peers, one expert on the specific topic and the other on methodology. The academic peers evaluated the paper from the thematic and methodological perspective. This process followed the guidelines set forth by the editorial committee of the Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology (http://www.revcolanest.com.co/es/guia-autores).

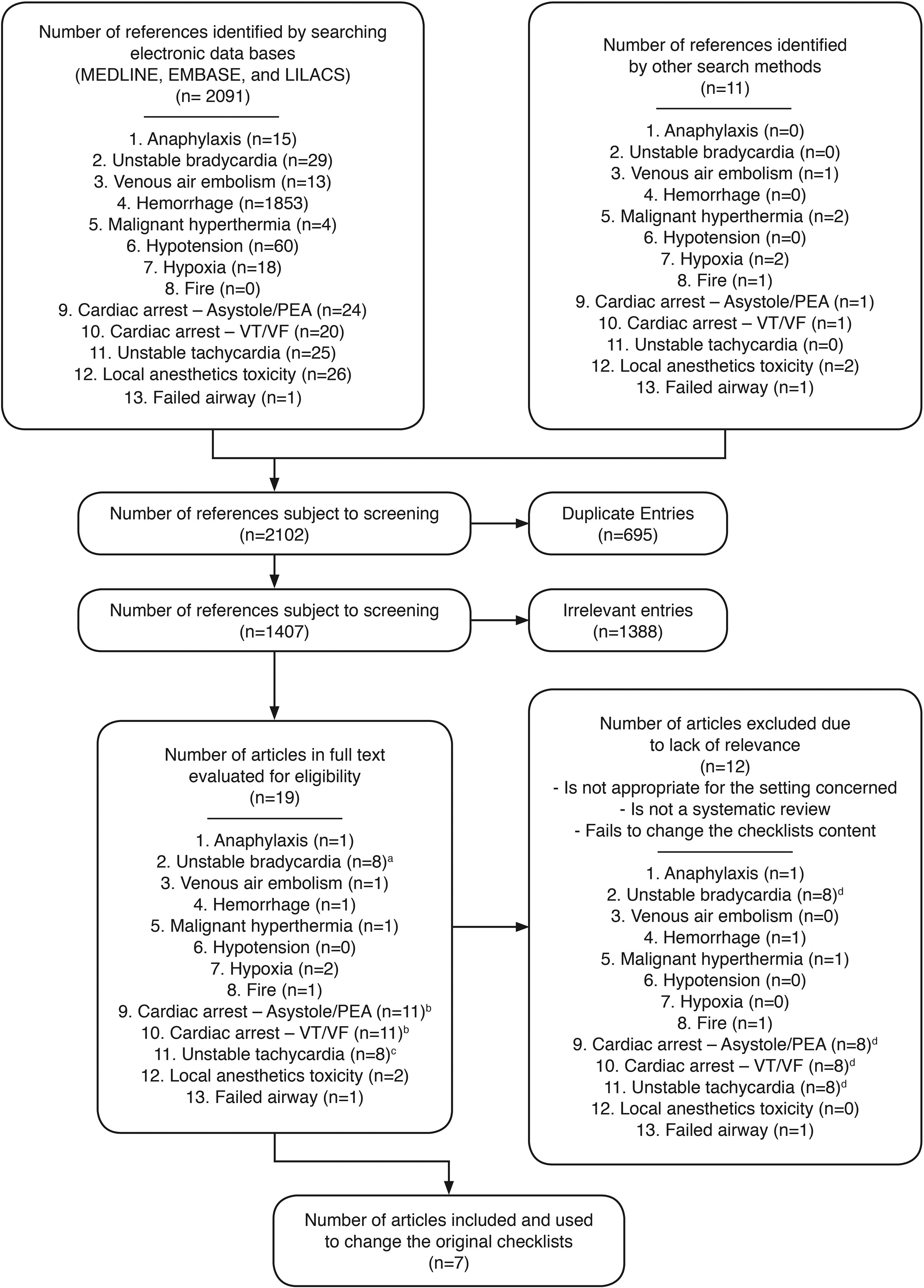

ResultsThe systematic search of electronic databases identified a total of 2091 articles. Through manual search strategies and snow-ball, 11 additional articles were identified. After eliminating the duplicate entries, the titles and abstracts of 1407 references were selected. Following the screening process, 19 full text articles were obtained, of which seven were finally included and used to change the original checklists (Fig. 1).23,35–40

Systematic search results. aThe 8 articles evaluated for unstable bradycardia are included among the 11 articles evaluated for the cardiac arrest checklists. bThe 11 articles evaluated for both cardiac arrest checklists are the same. cThe 8 articles evaluated for unstable tachycardia are comprised in the 11 articles evaluated for the cardiac arrest checklists. dThe 8 articles excluded from the checklists for bradycardia, tachycardia, and cardiac arrest are the same.

The checklists were reorganized in alphabetical order according to the Spanish title. The tables used as reference information under the title of “critical changes” in the original checklists, were translated into Spanish as “eventos críticos” in order to avoid user confusion.

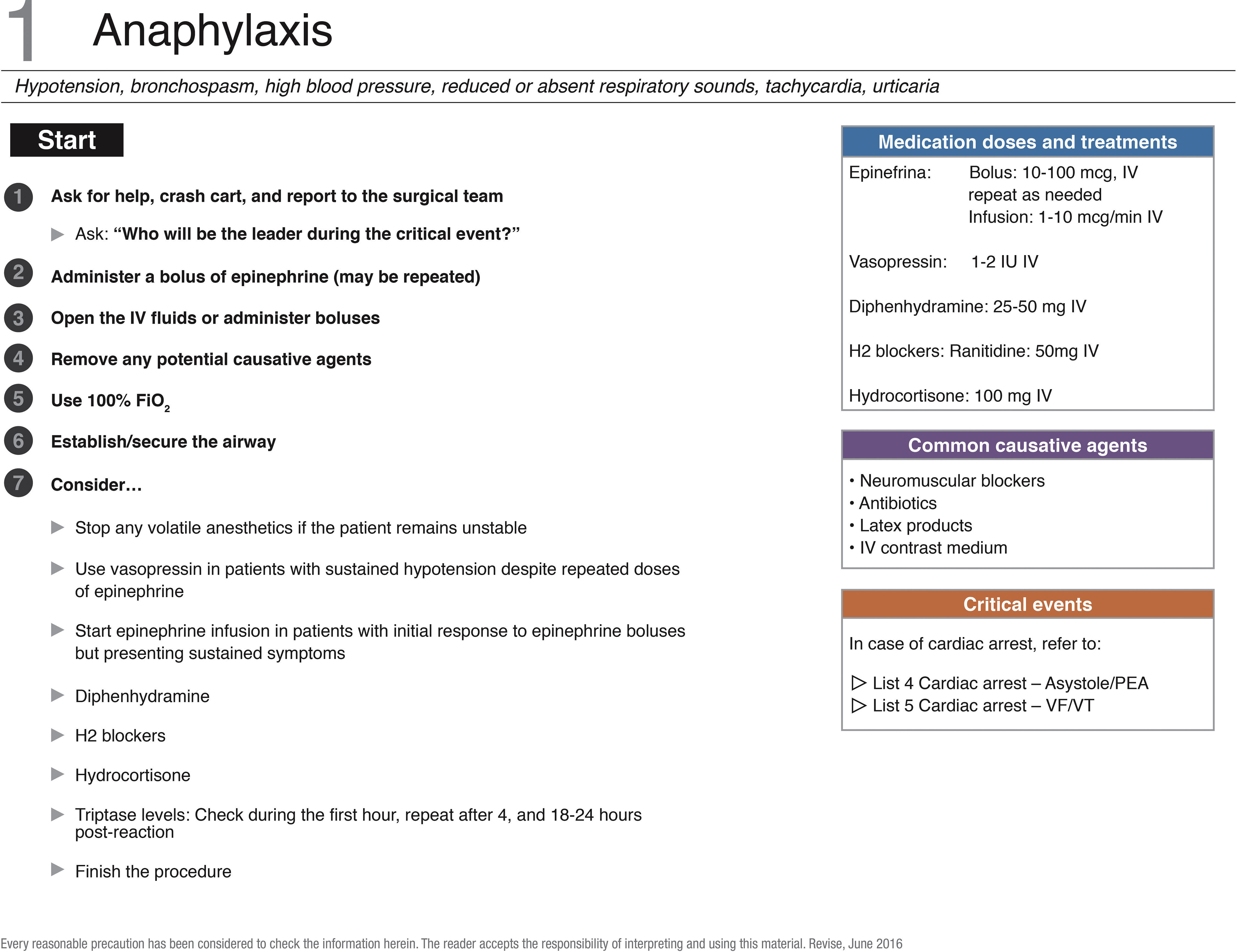

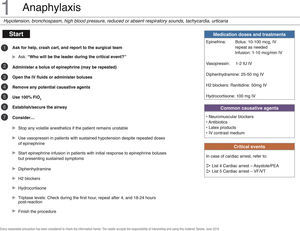

To update the checklist for managing anaphylaxis, a full text article was evaluated.41 The review generated no changes in the actions submitted in the original list. The checklist layout in Spanish is depicted in the corresponding figure (Fig. 2).

Checklist for managing anaphylaxis. PEA, pulseless electrical activity; FiO2, oxygen inspired fraction; FV, ventricular fibrillation; IV, intravenous; VT, ventricular tachycardia. Source: Translated and updated with authorization based on “OR Crisis Checklists” available at: www.projectcheck.org/crisis.

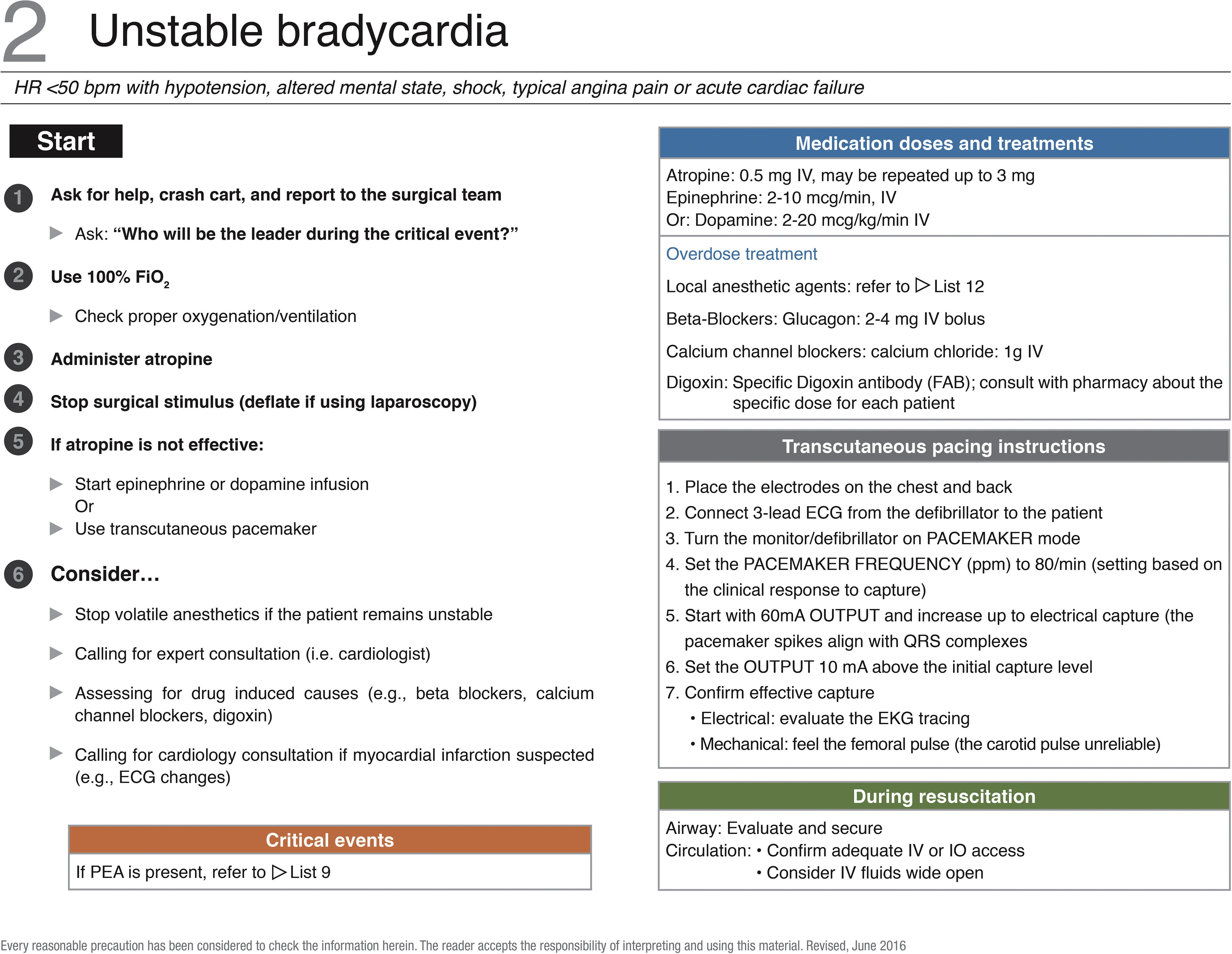

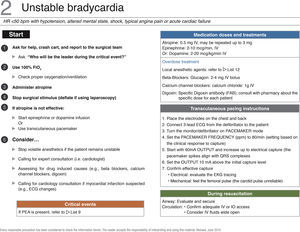

8 articles for managing bradycardia were identified and revised to consider probable changes to the original English checklist.37,39,42–47 However, no secondary evidence was found to change, add, or delete any action proposed in the original list. The corresponding figure exhibits the Spanish checklist (Fig. 3).

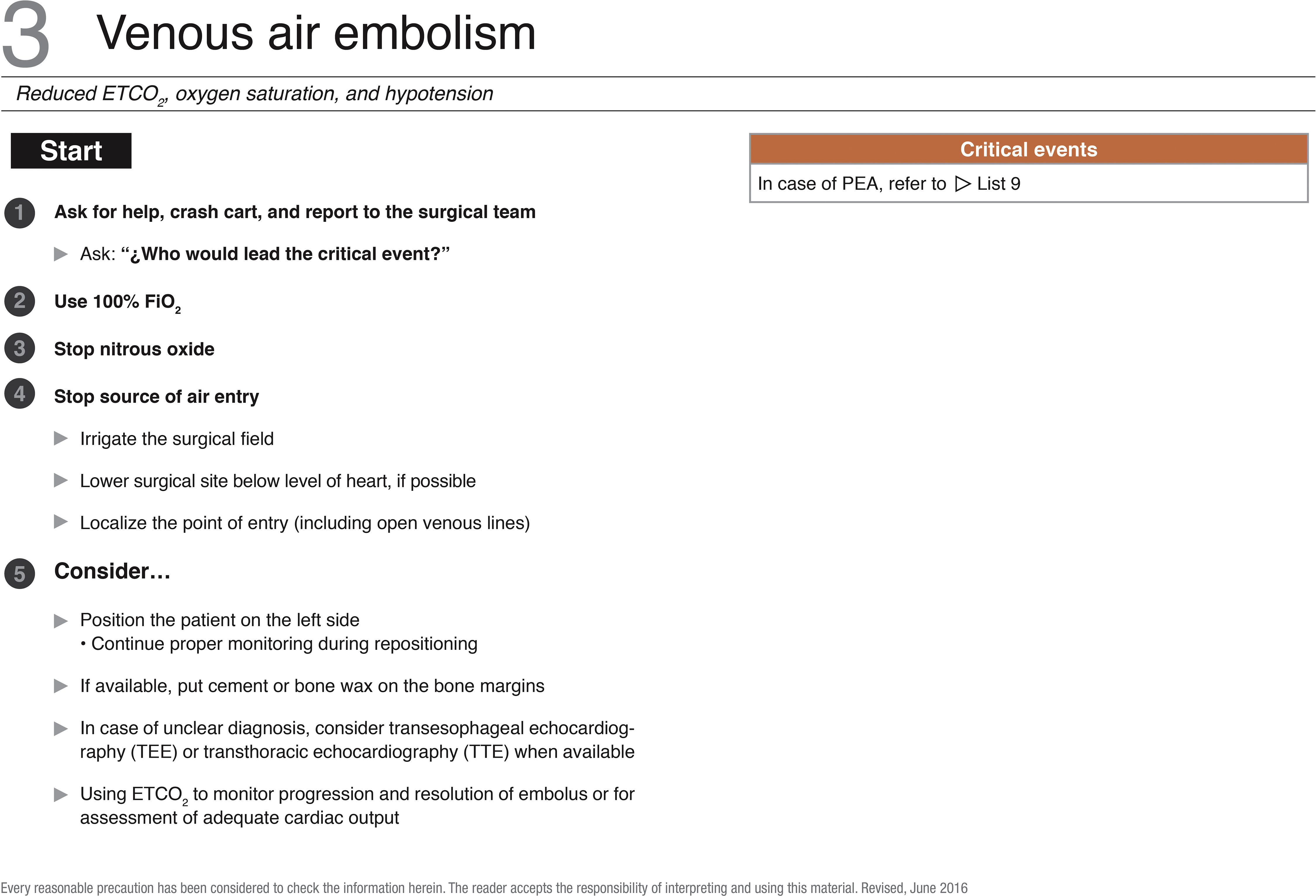

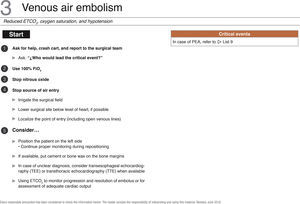

An article evaluated as full text was used to change one action in the checklist for the management of venous air embolism. Additionally, the possibility to consider transthoracic echocardiography in cases of uncertain diagnosis36 was introduced (Fig. 4).

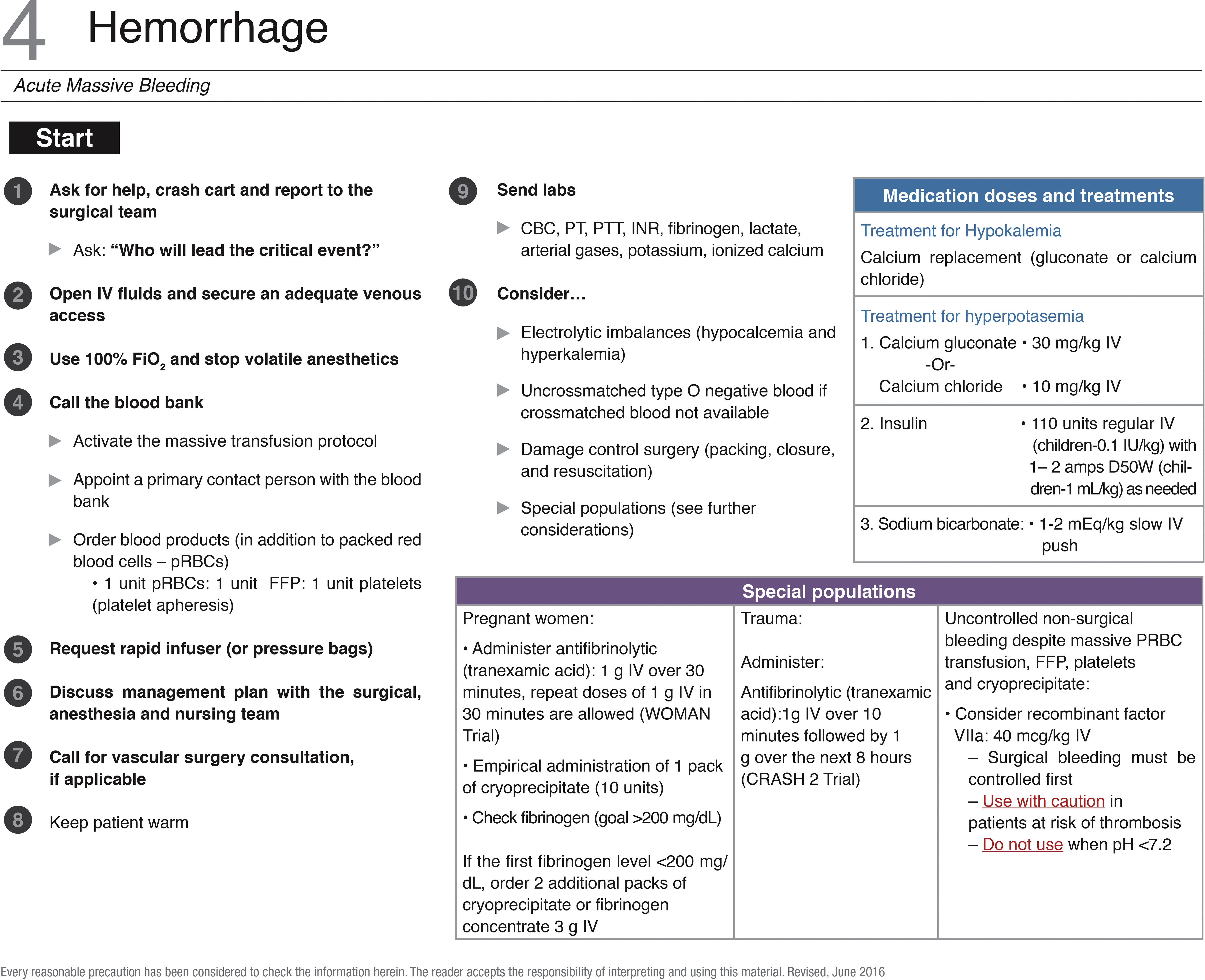

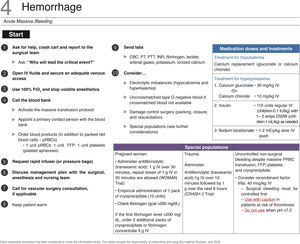

1853 references were identified on the management of bleeding in the OR and were subject to screening for complete text review and discussion.48 None of the actions in the original checklist was changed. The list in Spanish is exhibited with the respective figure (Fig. 5).

Checklist for hemorrhage management. DDW, dextrose in distilled water; FiO2, inspired oxygen fraction; VF, ventricular fibrillation; IV, intravenous; VT, ventricular tachycardia. Source: Translated and updated with authorization from “OR Crisis Checklists” availale at: www.projectcheck.org/crisis.

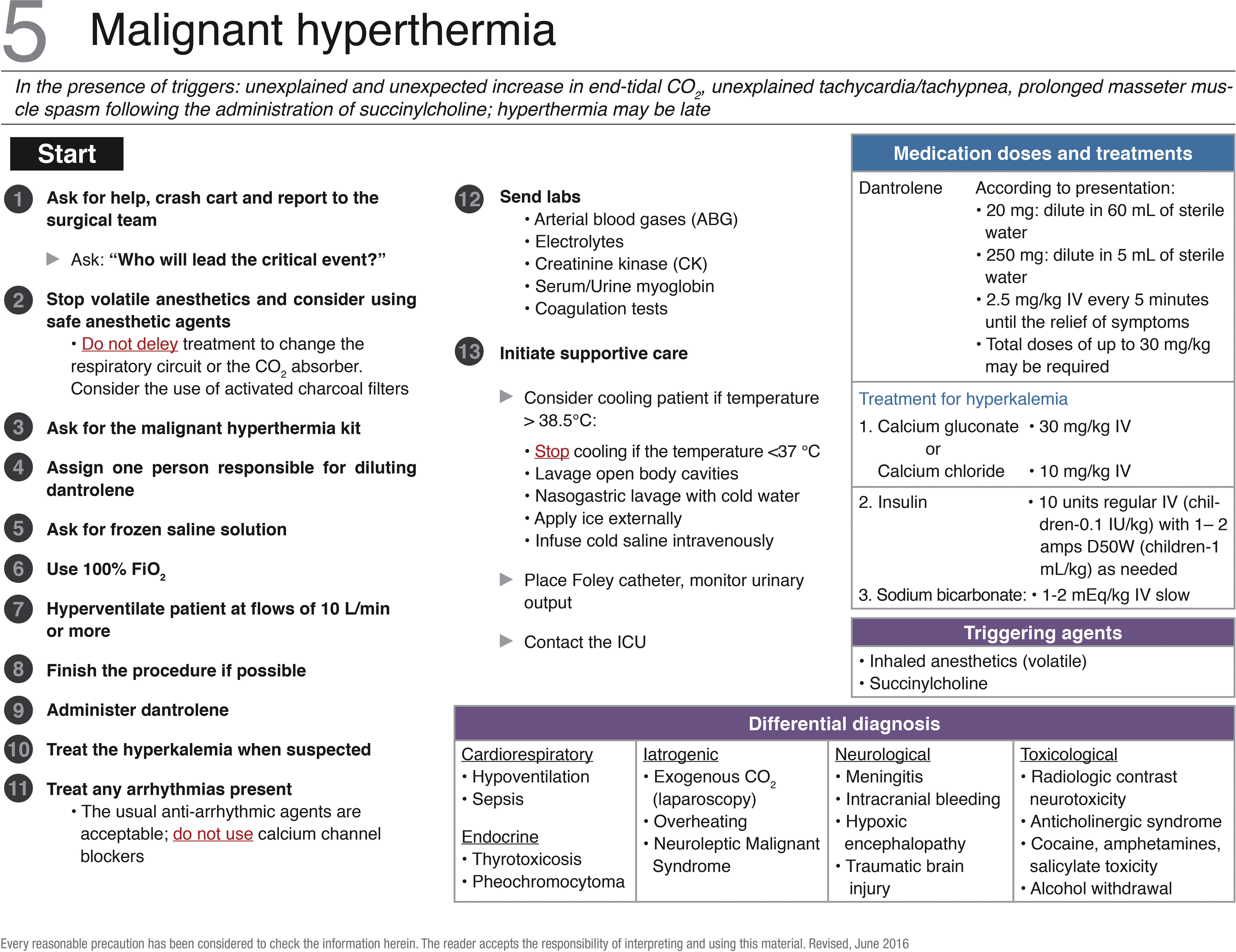

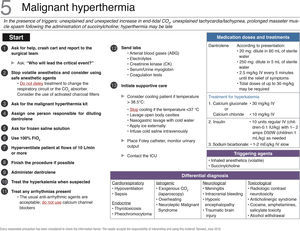

A full text reference was identified and analyzed for the list of intraoperative management of hyperthermia crisis. Based on this reference,38 the order of the initial actions for crisis management was changed. In the original checklist, suspending volatile anesthetics and the use of safe anesthetic agents is in the fifth place but for the Spanish list, this became the second action following the activation of the aid system. The probability to consider the use of activated carbon filter in the respiratory circuit was also added, together with information about the clinical use of concentrated dantrolene (250mg per vial). The contact number for the crisis hot line of the US Malignant Hyperthermia Association (MHAUS) was removed. The Spanish checklist is exhibited in the figure attached (Fig. 6).

Checklist for the management of malignant hyperthermia. DDW, dextrose in distilled water; ETCO2, end-tidal carbon dioxide; FiO2, inspired oxygen fraction; VF, ventricular fibrillation; IV, intravenous; ICU, intensive care unit. Source: Translated and updated with authorization from “OR Crisis Checklists” available at: www.projectcheck.org/crisis.

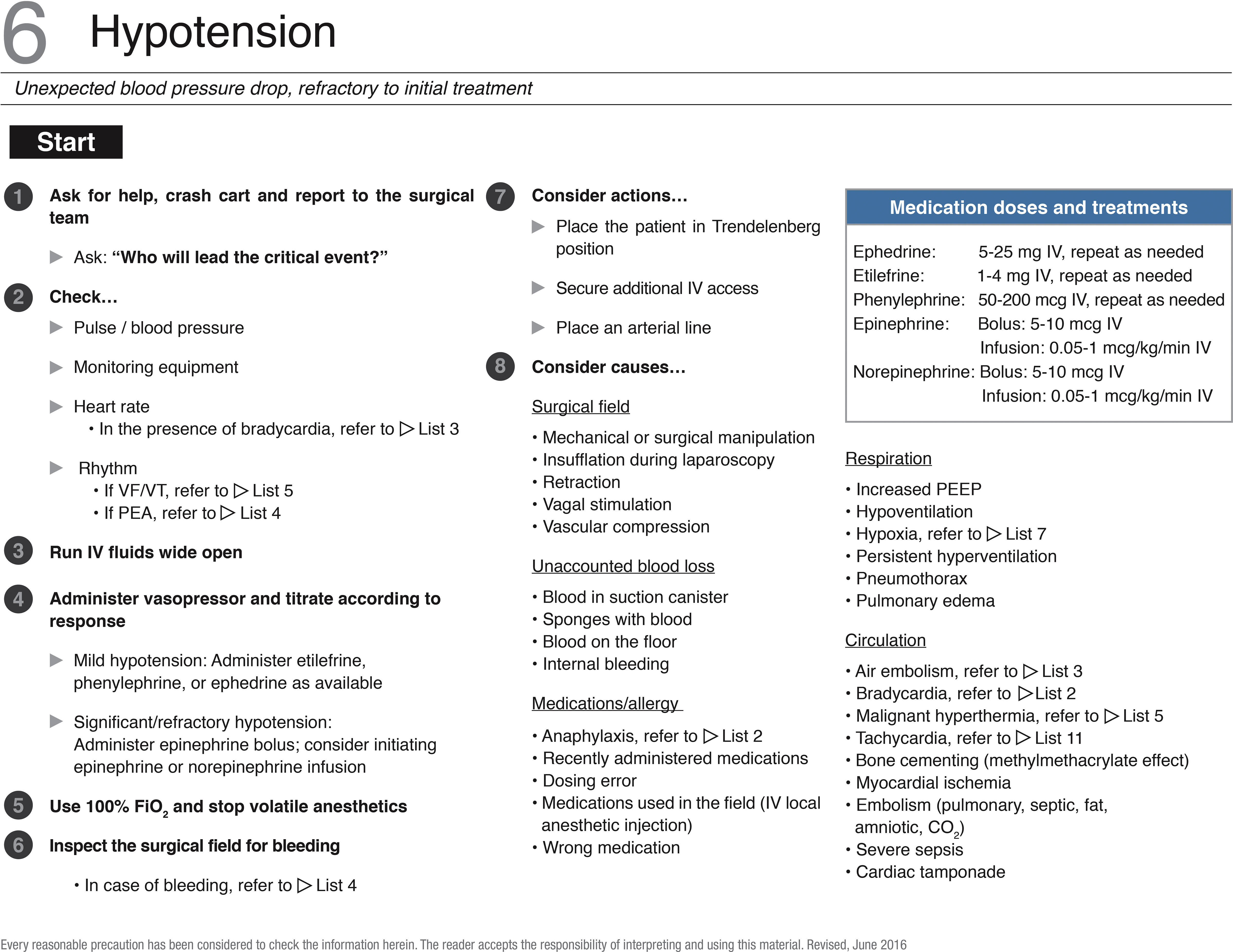

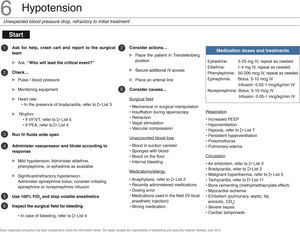

The Spanish checklist for intraoperative management of hypotension is in the corresponding table. None of the articles lead to changes in the original list. Etilefrine and norepinephrine were added as reference information for selecting the pharmacological intervention (Fig. 7).

Checklist for the management of hypotension. PEA, pulseless electrical activity; FiO2, inspired oxygen fraction; VF, ventricular fibrillation, IV, intravenous; VT, ventricular tachycardia. Source: Translated and updated with authorization, based on “OR Crisis Checklists” available at: www.projectcheck.org/crisis.

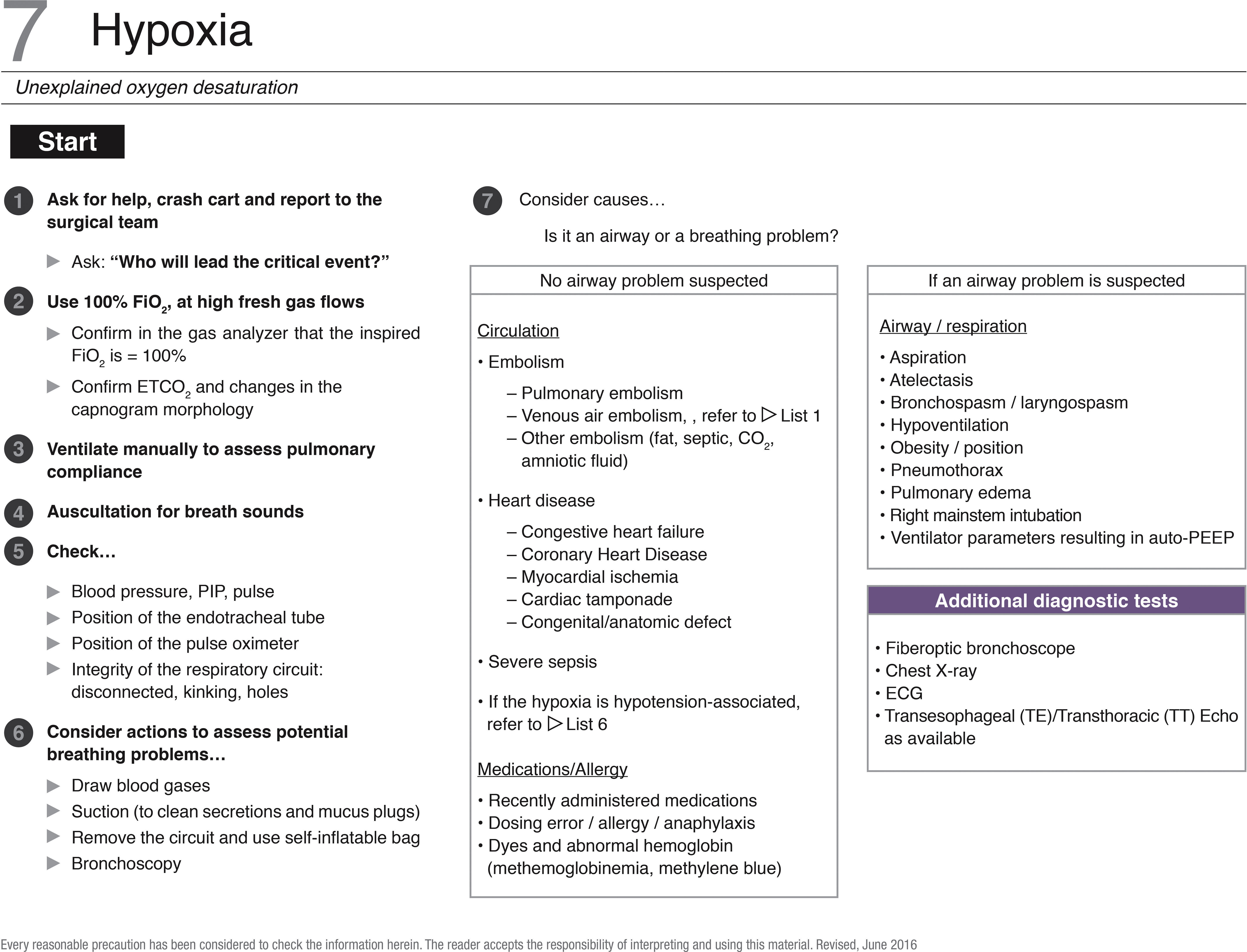

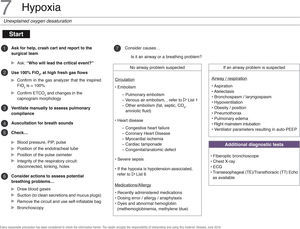

Full text articles were not evaluated for the checklist for management of hypoxia. Just as with the list for managing venous air embolism, the possibility to use transthoracic echocardiography for diagnostic evaluation was included in the reference information.36 The Spanish list is available at the end of this document (Fig. 8).

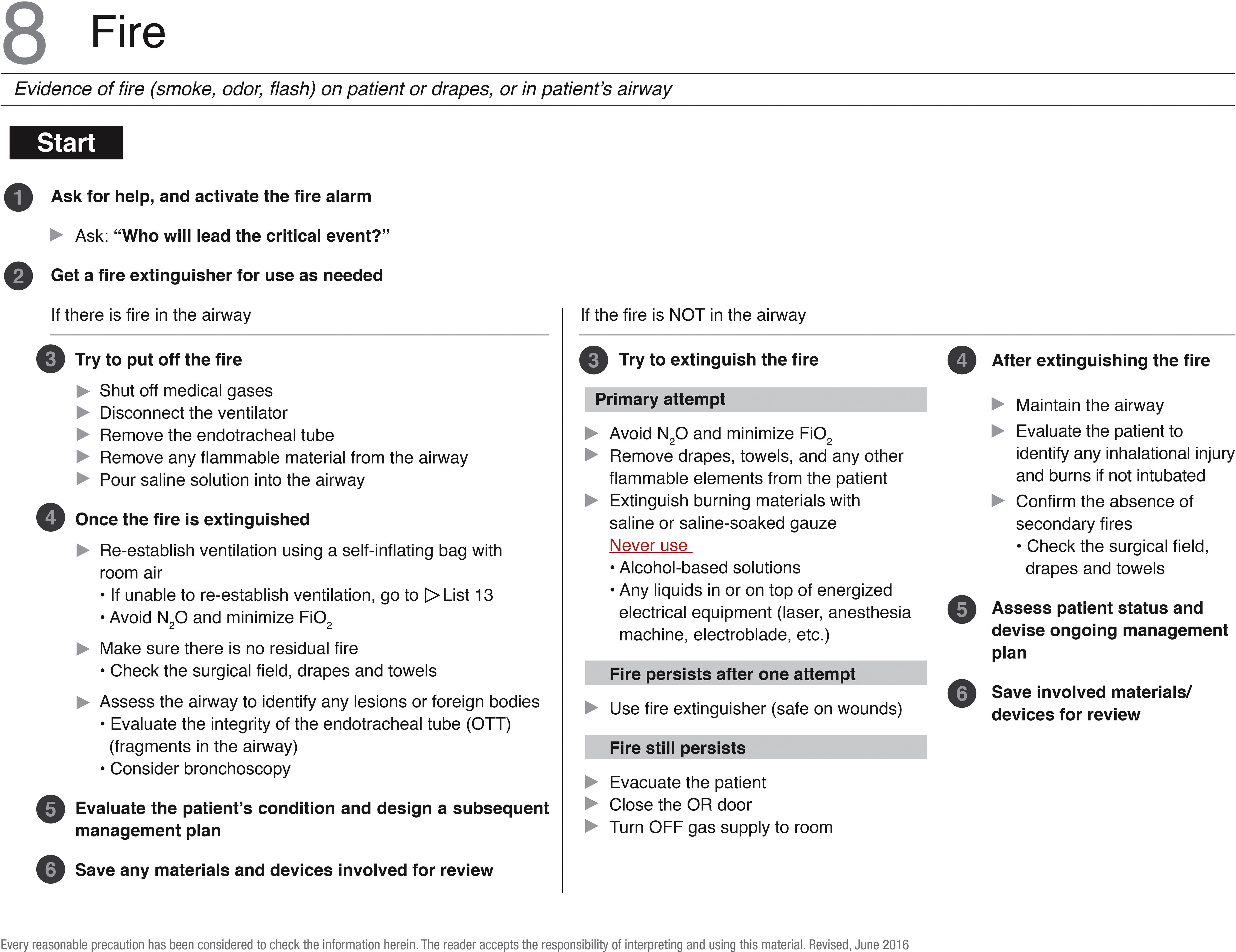

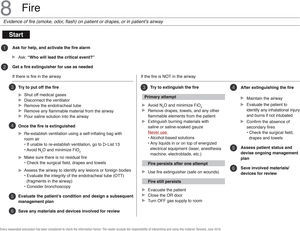

A full text article on fire in the OR was evaluated.49 The checklist translated into Spanish was not amended versus the original checklist (Fig. 9).

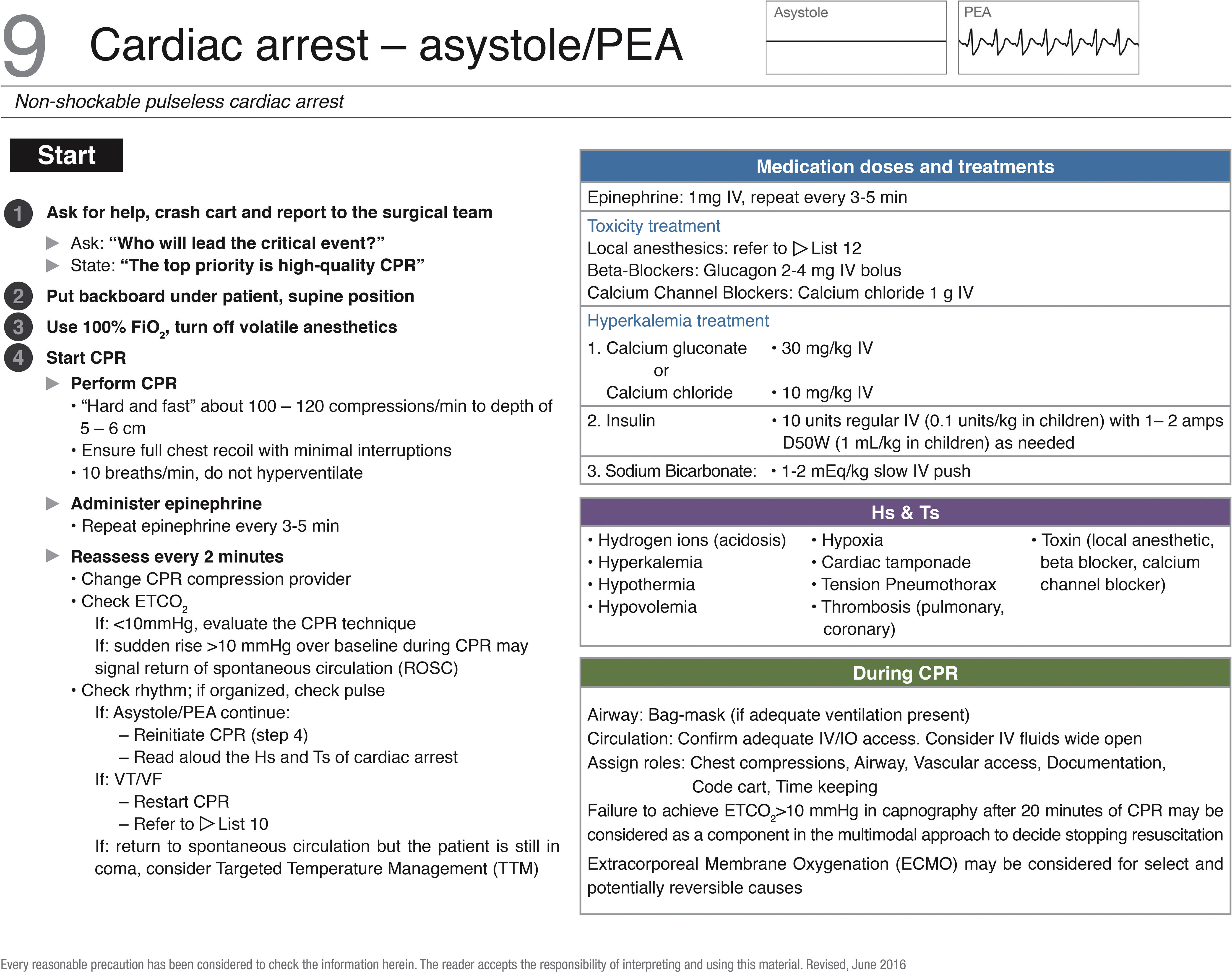

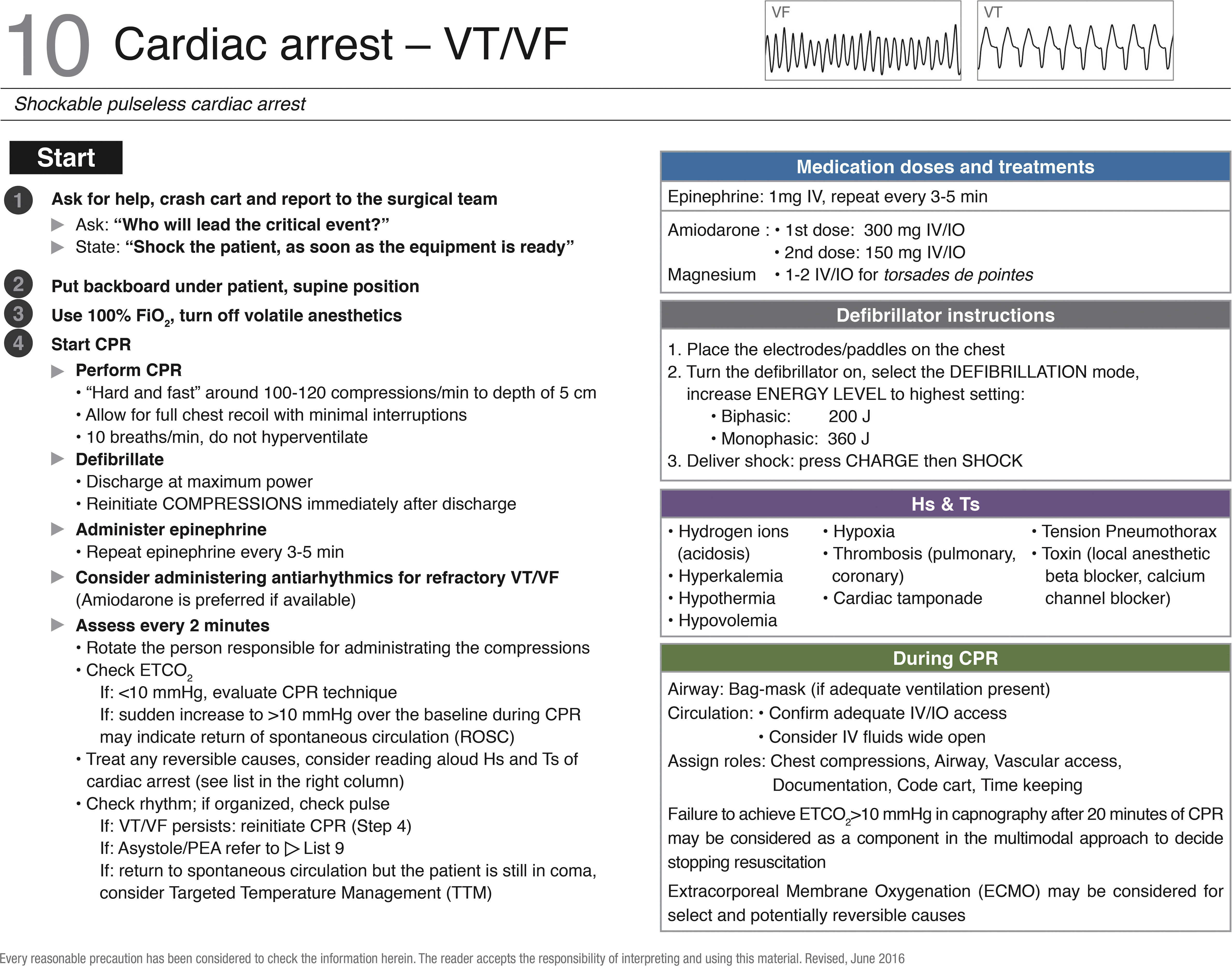

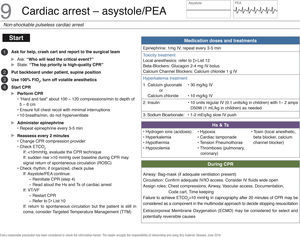

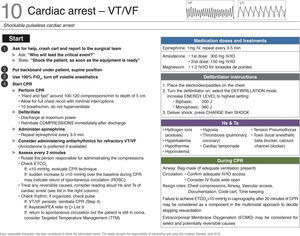

In order to update the checklists for managing intraoperative cardiac arrest, the complete text of the 2015 guidelines was evaluated37,39,42–47,50,51 and a second additional article on the management of body temperature during the post-arrest period.40 In terms of the original lists, the number of thoracic compressions per minute was changed from a fixed value of 100 to a range of 100–120 compressions per minute. The number of breaths per minute was changed from 8 to 10. The use of vasopressin was eliminated in both scenarios of cardiac arrest. Information about some considerations to be kept in mind with the multimodal approach, to decide whether to stop the resuscitation. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was also included as an option to consider in the treatment of selected and potentially reversible causes (Figs. 10 and 11).

Checklist for managing cardiac arrest – VT/VF. ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FiO2, inspired oxygen fraction; VF, ventricular fibrillation; IV, intravenous; IO, intraoseous; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; VT, ventricular tachycardia. Source: Translated and updated with authorization from “OR Crisis Checklists” available at: www.projectcheck.org/crisis.

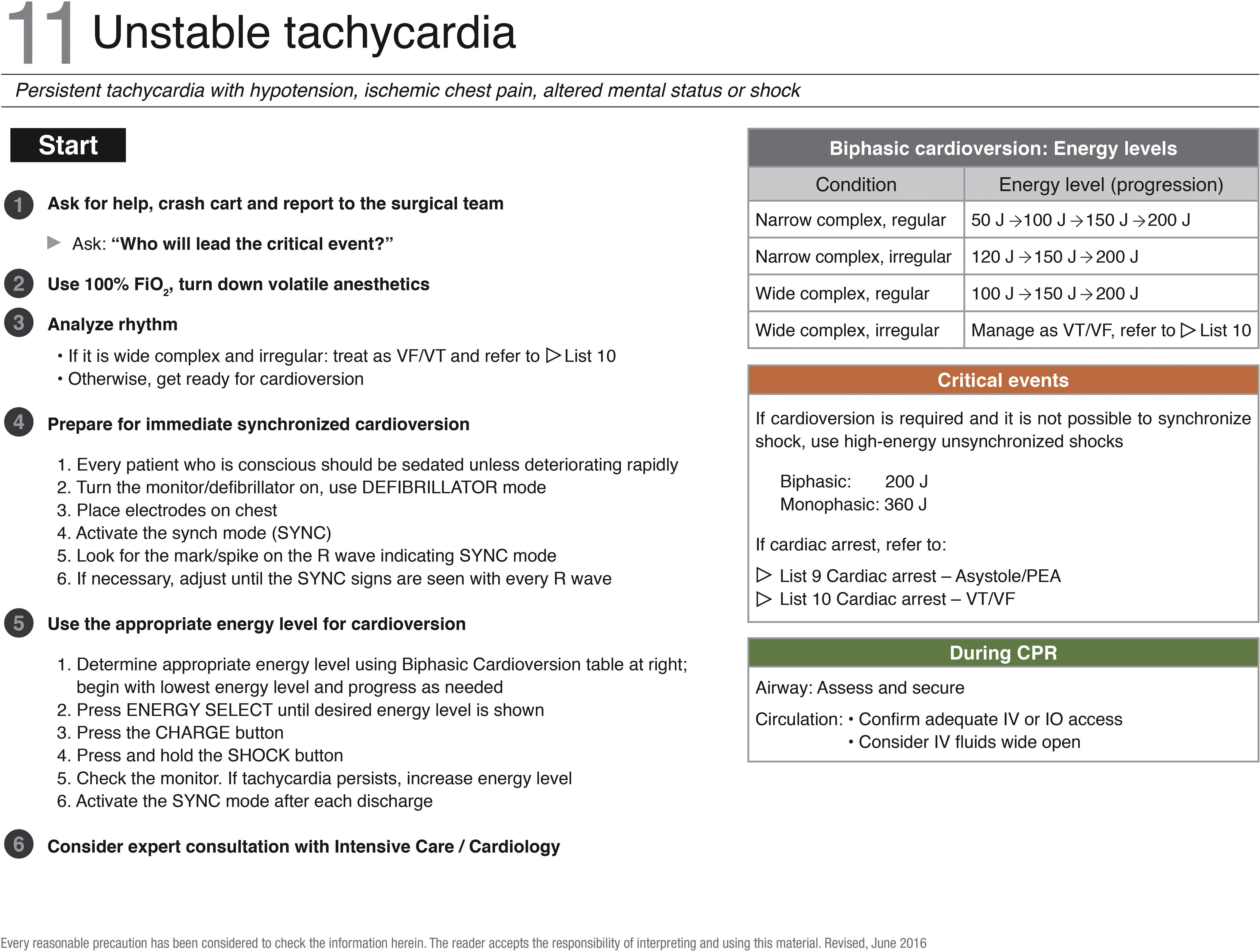

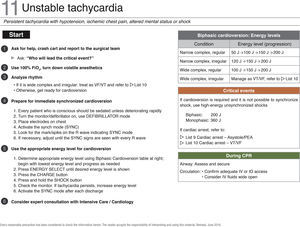

8 full text articles were evaluated for the translation of the checklist for management of unstable tachycardia.37,39,42–47 The information collected did not change the actions considered in the original list (Fig. 12).

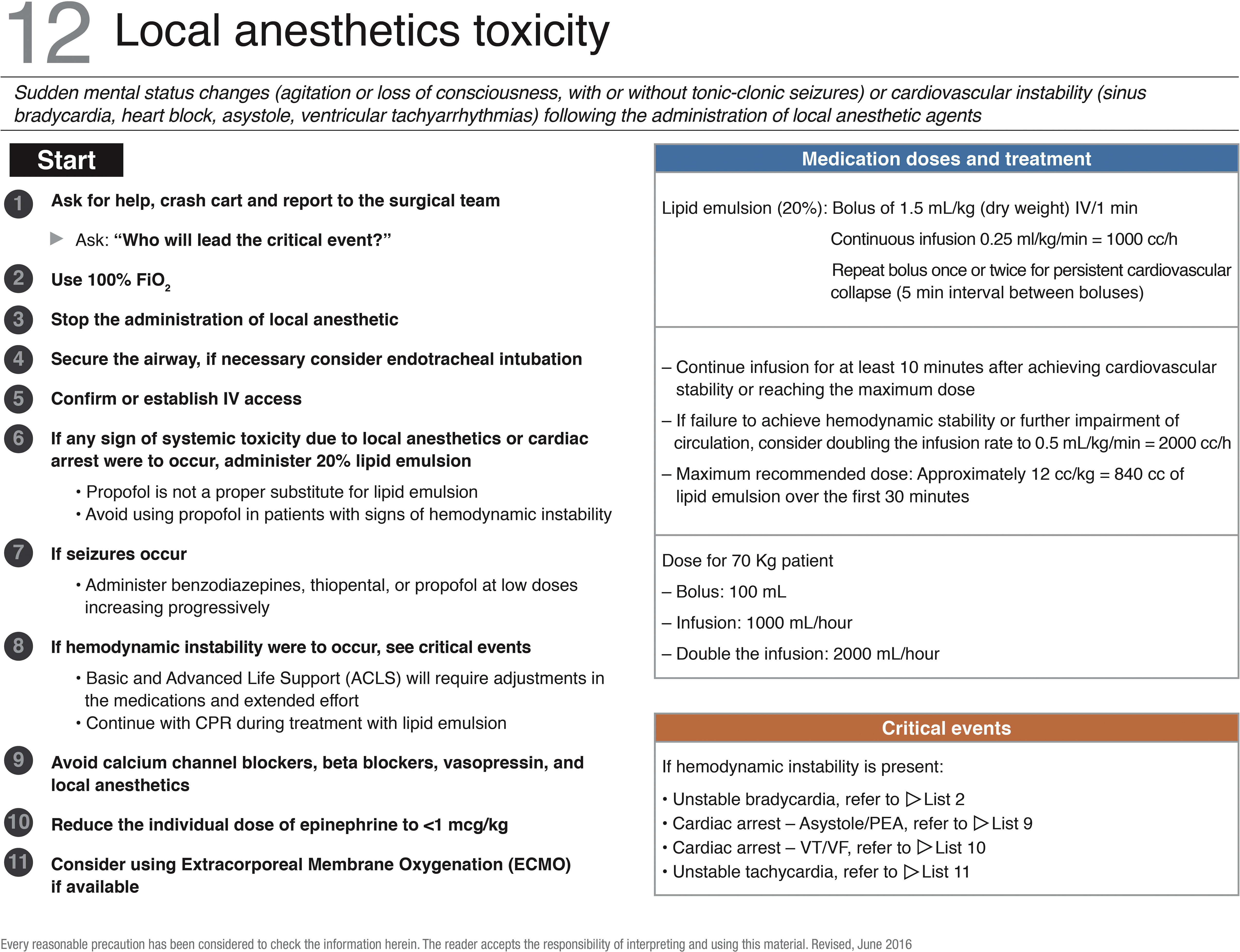

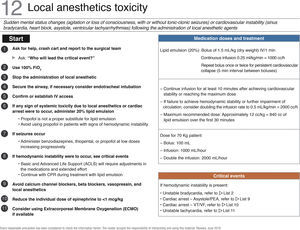

The checklist for managing anesthetic systemic toxicity in the OR is available at the end of this document. 11 actions were included based on two checklists selected a priori.23,35 The actions for the new Spanish list were generated in accordance with the structure proposed by the original Ariadne Labs. The layout was adapted to the design style of the other checklists. Reference information about the clinical used of 20% lipid emulsion was included, in addition to potential critical events that may occur during an intraoperative local anesthetics crisis (Fig. 13).

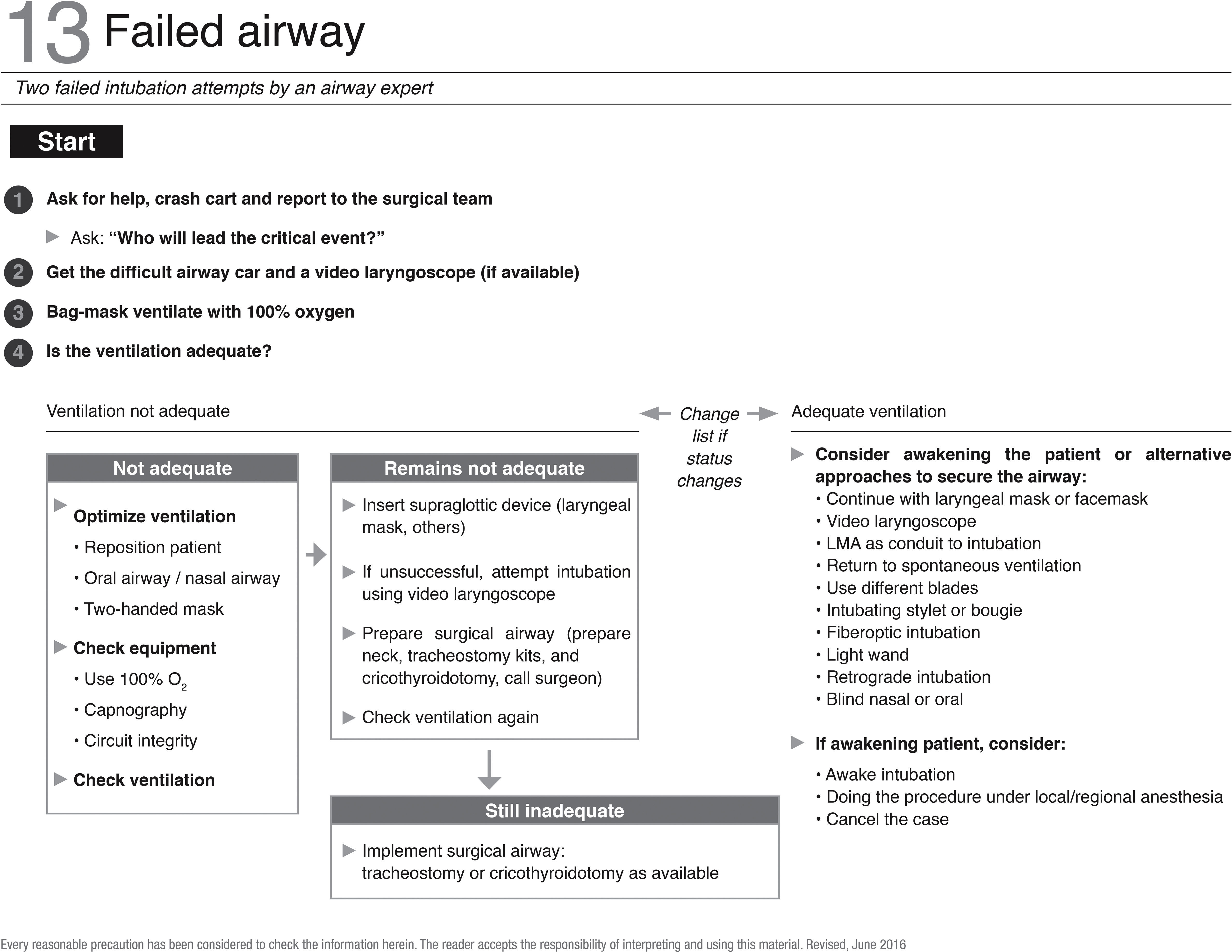

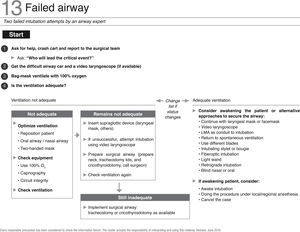

A full text article was evaluated on failed airway management.52 The actions in the original list were not amended. The file used at the basis to print the translated and updated checklists in the form of a booklet, is available as an appendix in this document (Fig. 14).

Implementation guidelinesThe implementation guidelines are based on the recommendations form Ariadne Labs.33 It is recommended to organize a multidisciplinary team prior to implementation. Such team shall be in charge of coordinating the implementation efforts and should comprise several anesthesiologists, OR nurses, and ideally a hospital administrator.33 Depending on the individual institutional culture, you may consider including representatives from other disciplines in the team, for instance a specialized surgeon. Team members shall be highly motivated, though it is not a requirement to have held a leadership position in the institution.33

It may be necessary to adapt the contents of the checklists to the particular clinic of hospital prior to their implementation. Changes in some actions may be relevant, for instance with regards to the specific information about available equipment and supplies, as well as institutional telephone numbers.33

There are multiple approaches to the use of the checklist in the OR. In order to achieve the best performance, the implementation team shall consider some specific aspects. Any decision regarding such consideration shall be adopted upon evaluating their impact on simulated emergency situations. The opinion of potential checklist users should also be taken into account, in terms of their expectations for availability and use.33

Location, presentation, and number of brochures availableThere are many locations where checklists may be posted in the OR. Consider the possibility of having several copies of the brochures. Usually a hard copy of the checklist shall be made available next to every anesthesia machine. Furthermore, each person involved in the care of surgical patients may have a digital copy available in his/her own mobile device.

Using checklists during a critical eventIt is advisable that the person reading the checklist during a critical event does not directly participate in the patient care. The list reader may be for instance the head nurse or a nursing assistant, medical student, intern, resident, or any team member able to use his/her time in directly reading the checklists.

Dissemination planAs a general rule, everyone working in the OR must be aware of checklists available for use. In order to accomplish this goal, a few activities may be organized:

Presenting the checklists at formal work meetings with the healthcare staff and hospital leadership.

Talking personally with the surgical team members about the checklists asking for their collaboration in the implementation thereof. This may some individuals less reluctant to using them.

Make an announcement about the fact that the checklists will be used in the institution. There are several ways to make this information available, including; internal newsletters, memoranda, posters, screen savers and badges.

Assess the impact of the implementationIt is critical to keep the information on the impact of the checklists at the site of implementation. This information shall be shared with the members of the surgical team, and particularly with the institutional leadership, since this furthers institutional support to the project.

Long term strategyThe initial implementation is critically important to the success of this type of initiatives. Likewise, consider the possibility of providing regular training with surgical team members.

DiscussionAs a result of this initiative by S.C.A.R.E. some checklists were translated and adapted to the Colombian Spanish terminology, in addition to updated based on the current evidence. The expectation is that the information contained in the new checklists have a stronger content validity as compared with doing the translation without going through a systematic review, leading to enhanced probabilities of recommending actions consistent with the current knowledge.

Although cognitive aids are a very important tool in the management of critical events, having available checklists properly translated and updated does not necessarily ensure having better outcomes in surgical patients. The leaders of the surgical departments must be aware of the need to establish a sound implementation program for checklists.24

The evidence of the positive impact of checklists on the performance of the staff responsible for the clinical management of surgical patients is consistent. However, there have been cases in which this positive impact is not materialized. For example, a misdiagnosis of a critical event may result in the selection and use of the inadequate checklist for the particular critical situation. The fat that strategies such as the use checklists have been adopted in the airplane industry may not be extended to a wrongful and potentially dangerous analogy.53 Clearly patients are not airplanes, and anesthesiologists are not pilots.54 It is impossible for a checklist to perfectly fit any critical situation that may arise in the OR. Consequently, despite the usefulness of checklists and other cognitive aids, proper skill-based training (knowledge, skills, and attitudes),55 clinical experience, and a commitment to patient safety, are still key for the management of critical events in the OR.56

In summary, the new translated and updated checklists resulting from S.C.A.R.E.’s initiative, are available to all the members of the healthcare staff for implementation at simulation educational settings and in clinical practice, as an additional tool in our quest for better outcomes in patients undergoing treatment in the OR.

FundingThis study was funded by the Colombian Society of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation (S.C.A.R.E.), and developed by the Instituto de Investigaciones Clínicas (Institute of Clinical Research) in partnership with the Review Group STI Cochrane, Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Conflicts of interestPrior to the development of this document, all authors competed a form to disclose any conflicts of interest. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Please cite this article as: Hepner DL, Rubio J, Vasco-Ramírez M, Rincón-Valenzuela DA, Ruiz-Villa JO, Amaya-Restrepo JC, et al. Listas de chequeo de la Sociedad Colombiana de Anestesiología y Reanimación (S.C.A.R.E.) para el manejo de eventos críticos en salas de cirugía: Traducción y actualización basada en la evidencia. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2017;45:182–199.