Lactic acidosis is defined as the presence of pH <7.35, blood lactate >2.0mmol/L and PaCO2 <42mmHg. However, the definition of severe lactic acidosis is controversial. The primary cause of severe lactic acidosis is shock. Although rare, metformin-related lactic acidosis is associated with a mortality as high as 50%. The treatment for metabolic acidosis, including lactic acidosis, may be specific or general, using sodium bicarbonate, trihydroxyaminomethane, carbicarb or continuous haemodiafiltration. The successful treatment of lactic acidosis depends on the control of the aetiological source. Intermittent or continuous renal replacement therapy is perfectly justified, shock being the argument for deciding which modality to use. We report a case of a male patient presenting with metformin poisoning as a result of attempted suicide, who developed lactic acidosis and multiple organ failure. The critical success factor was treatment with continuous haemodiafiltration.

Definimos acidosis láctica en presencia de pH <7.35, lactato en sangre >2.0mmol/L y PaCO2 <42mmHg. Por otro lado, la definición de acidosis láctica grave es controvertida. La causa principal de acidosis láctica grave es el estado de choque. La acidosis láctica por metformina es rara pero alcanza mortalidad del 50%. La acidosis metabólica incluyendo a la acidosis láctica puede recibir tratamiento específico o tratamiento general con bicarbonato de sodio, trihidroxiaminometano, carbicarb o hemodiafiltración continua. El éxito del tratamiento de la acidosis láctica yace en el control de la fuente etiológica; la terapia de reemplazo renal intermitente o continua está perfectamente justificada, donde el argumento para decidir cuál utilizar será el estado de choque. Presentamos el informe de un caso de un paciente masculino con intoxicación por metformina como intento suicida, quien desarrolló acidosis láctica y falla orgánica múltiple en cuya base para el éxito del caso fue el tratamiento con hemodiafiltración continua.

Lactic acidosis is defined as the presence of pH <7.35, blood lactate >2.0mmol/L and PaCO2 <42mmHg. However, the definition of severe lactic acidosis is controversial. Many physicians associate the severity of lactic acidosis with pH <7.2 or with deleterious effects, mainly haemodynamic, requiring immediate treatment.1–3 The main cause of severe lactic acidosis is shock, associated with a mortality as high as 50% despite adequate aetiological treatment, and 100% when pH is lower than 7.0.4,5

However, an uncommon cause of lactic acidosis is metformin poisoning, with a mortality as high as 50%. The incidence is 3 cases for every 100,000 patients treated per year. The main risk factor for the occurrence of metformin-related lactic acidosis is the renal impairment present in diabetic patients. Voluntary poisoning is rare and its characteristics and prognosis are seldom reported in the literature. It appears that blood levels of metformin are not a determining factor of the outcome in the intoxicated patient, whereas blood lactate >15mmol/L, pH <7.2, organ dysfunction (≥4 points), and lower prothrombin activity (≤50%) are considered risk factors for mortality.6,7 We report the case of a patient intentionally poisoned with metformin who developed multiple organ dysfunction, in whom the critical success factor to resolve the clinical picture was continuous haemodiafiltration.

Clinical caseWe present the case of a 74-year-old male patient coming from Veracruz, Mexico, with a history of diabetes mellitus type 2 diagnosed 26 years before, treated with metformin 850mg/day and glibenclamide 10mg/day, a diagnosis of schizophrenia-type psychiatric disorder irregularly treated with olanzapine, and no other relevant history. Following the intentional intake of 20 tablets of metformin, the patient developed a clinical picture characterised by nausea, vomiting and drowsiness, followed 24h later by epistaxis, diaphoresis, and loss of consciousness which prompted transfer for assessment.

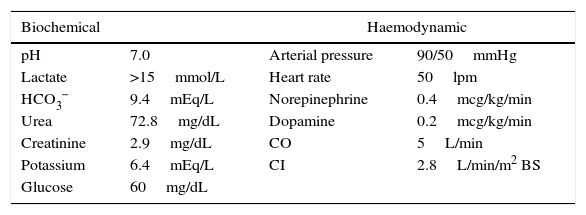

Upon arrival to the emergency department, the patient was placed on invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) because of his neurological condition, and required the use of vasopressors because of haemodynamic instability with altered nodal-type cardiac rhythm. The initial blood work revealed hyperlactatemia (>15mmol/L), hypoglycaemia, hyperkalemia and acute kidney injury (AKI 3) (Table 1).

Biochemical and haemodynamic variables for hospital admission.

| Biochemical | Haemodynamic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.0 | Arterial pressure | 90/50mmHg |

| Lactate | >15mmol/L | Heart rate | 50lpm |

| HCO3− | 9.4mEq/L | Norepinephrine | 0.4mcg/kg/min |

| Urea | 72.8mg/dL | Dopamine | 0.2mcg/kg/min |

| Creatinine | 2.9mg/dL | CO | 5L/min |

| Potassium | 6.4mEq/L | CI | 2.8L/min/m2 BS |

| Glucose | 60mg/dL | ||

pH: negative log of hydrogen ion concentrations; HCO3− bicarbonate; CO: cardiac output; CI: cardiac index; BS: body surface.

Source: Authors.

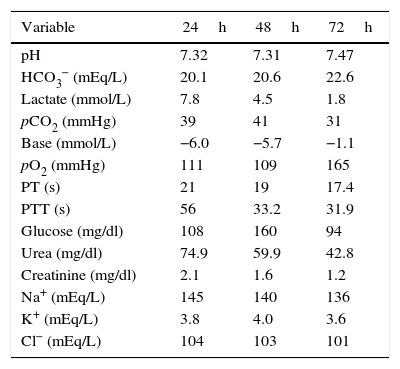

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with a diagnosis of severe lactic acidosis secondary to metformin intoxication, an APACHE II score of 25 and a SOFA score of 9. Slow continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) was started with haemodiafiltration using a Prisma-Flex® equipment; it was maintained for 48h with an effluent dose of 25ml/kg/h, achieving clinical and laboratory improvement characterised by a reduction in potassium levels, diminished nitrogen compounds, acidosis reversal, and lactate clearance of more than 50% in 24h and 90% at 48h. As a result, the patient was extubated, vasopressors were discontinued, and the patient was discharged from the ICU after 72h (Table 2). The patient gave his consent for the publication of the case report, and approval was also obtained from the hospital's local Ethics Committee.

Behaviour of the biochemical variables of the patient during slow CRRT and on discharge from the ICU.

| Variable | 24h | 48h | 72h |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.32 | 7.31 | 7.47 |

| HCO3− (mEq/L) | 20.1 | 20.6 | 22.6 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 7.8 | 4.5 | 1.8 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 39 | 41 | 31 |

| Base (mmol/L) | −6.0 | −5.7 | −1.1 |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 111 | 109 | 165 |

| PT (s) | 21 | 19 | 17.4 |

| PTT (s) | 56 | 33.2 | 31.9 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 108 | 160 | 94 |

| Urea (mg/dl) | 74.9 | 59.9 | 42.8 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| Na+ (mEq/L) | 145 | 140 | 136 |

| K+ (mEq/L) | 3.8 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| Cl− (mEq/L) | 104 | 103 | 101 |

pH: negative log of hydrogen ion concentrations: HCO3−: bicarbonate; pCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; pO2: partial pressure of oxygen; PT: prothrombin time; PPT: partial thromboplastin time; Na+: sodium; K+: potassium; Cl−: chlorine.

Source: Authors.

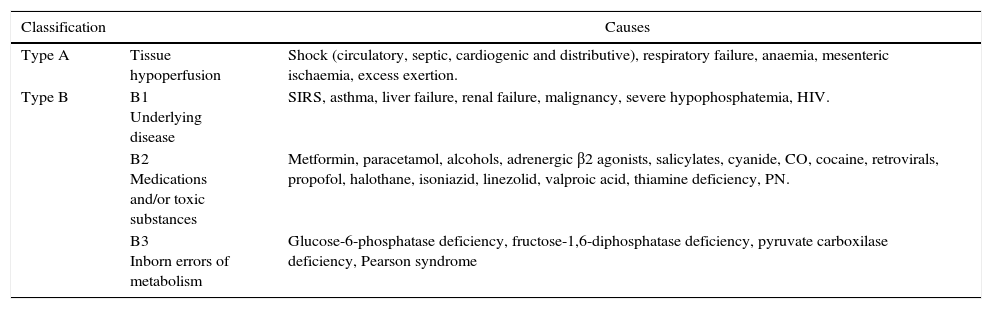

Metformin is a biguanide and the first drug of choice for blood sugar control in patients with DM type 2 because of its metabolic and cardiovascular benefits.8 The most frequent adverse effects related to its use are gastrointestinal, including nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. However, the most feared adverse effect is lactic acidosis.7,9 Pyruvate-derived lactate is the end product of glycolysis in anaerobic conditions. Humans produce 1500mmol of lactate per day (0.8mmol/kg/h) in muscle-skeletal tissue (25%), skin (25%), red blood cells (20%), brain (20%) and intestinal tissue (10%). To maintain balance, lactate needs to be removed, and this is done in organs like the liver (60%), kidneys (30%), heart and skeletal muscle (10%).10–12 Any imbalance in the form of increased lactate production, reduced clearance, or both, will give rise to serum lactate elevation (normal <2mmol/L). As a molecule, lactate is found in anion form and not as lactic acid. In the past, it was postulated that in order for lactic acid to occur, the hydrogen ions (H+) required for conversion had to be produced through adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis not used in the cytoplasm. Recently, an explanation for the development of acidosis has been postulated on the basis of Stewart's physicochemical theory, according to which pH changes depend on the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2), the total concentration of non-volatile weak acids, and the strong ion difference (SID), the latter being the cation–anion difference in the extracellular fluid (Na++K++Mg++Ca2+)−(Cl−+Lactate−). This means that an increase in lactate will reduce the SID and, in turn, pH, creating or perpetuating lactic acidosis.13 Traditionally and in accordance with Cohen's classification, lactic acidosis is divided into hypoxaemic type A and non-hypoxaemic type B14,15 (Table 3).

Aetiologic classification of metabolic acidosis.

| Classification | Causes | |

|---|---|---|

| Type A | Tissue hypoperfusion | Shock (circulatory, septic, cardiogenic and distributive), respiratory failure, anaemia, mesenteric ischaemia, excess exertion. |

| Type B | B1 Underlying disease | SIRS, asthma, liver failure, renal failure, malignancy, severe hypophosphatemia, HIV. |

| B2 Medications and/or toxic substances | Metformin, paracetamol, alcohols, adrenergic β2 agonists, salicylates, cyanide, CO, cocaine, retrovirals, propofol, halothane, isoniazid, linezolid, valproic acid, thiamine deficiency, PN. | |

| B3 Inborn errors of metabolism | Glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency, fructose-1,6-diphosphatase deficiency, pyruvate carboxilase deficiency, Pearson syndrome |

HIV: human immunodificiency virus; SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome; CO: carbon monoxide; PN: parenteral nutrition.

Source: Authors.

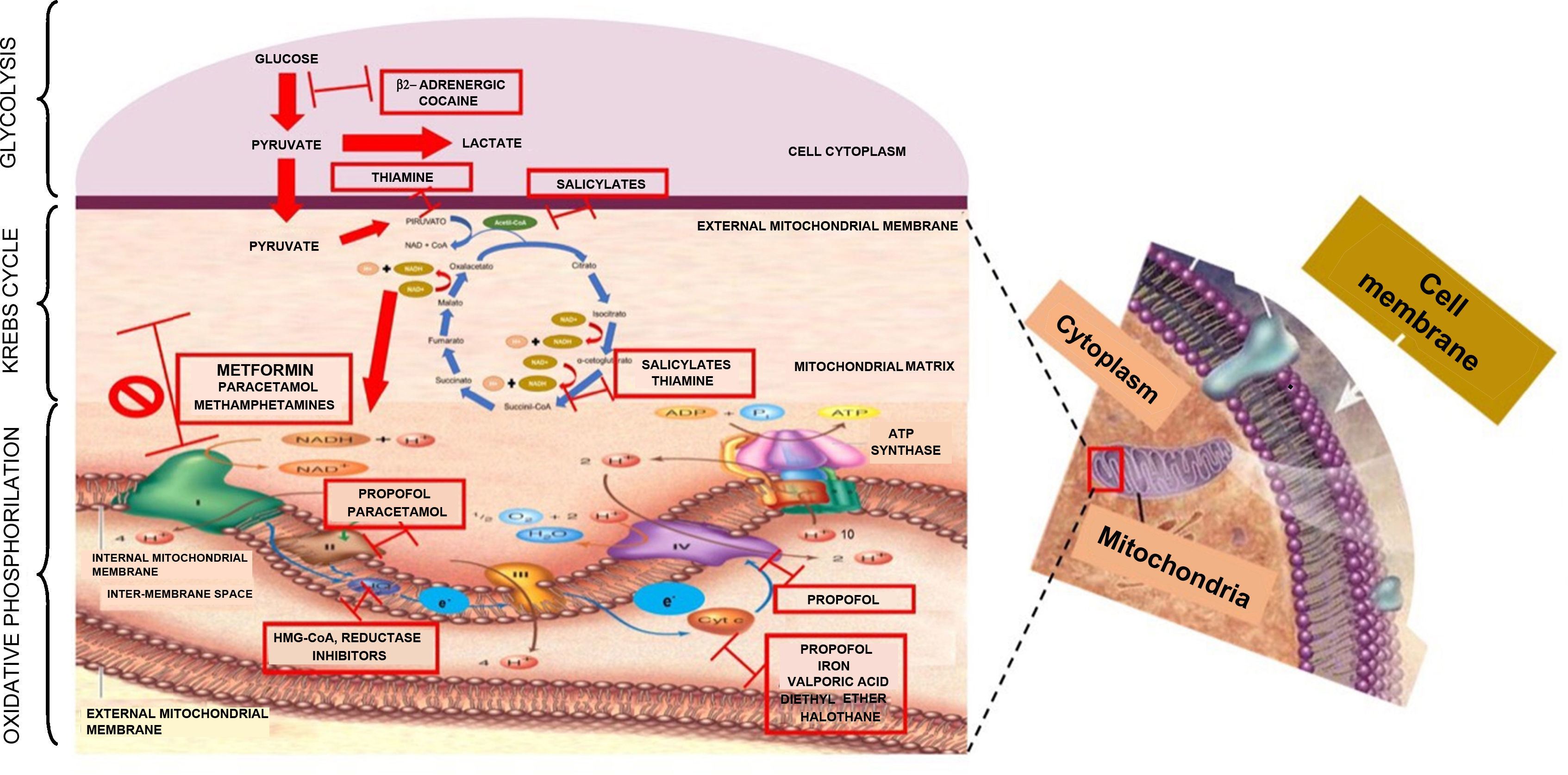

It has been considered that the mechanism for the production of lactic acidosis is multi-factorial: genetic, metabolic oxidation suppression, and Krebs cycle enzyme suppression.16,17 However, the most widely accepted mechanism is the one proposed by Owen,18 whereby metformin affects electron transport, increasing the concentration of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide or NADH+ and inhibits metabolic oxidation, inducing anaerobic metabolism. Understanding the process of cell respiration is important in order to understand the mechanism through which metformin poisoning causes lactic acidosis type B2. ATP is the “cell's top energy currency”, indispensable for physiological cell function. A process known as cell respiration is required in order to obtain this energy currency in aerobic metabolism. Cell respiration is defined as the generation of energy from nutrient oxidation and it consists of three stages: glycolysis, citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) and oxidative phosphorilation. Glycolysis consists of a set of enzymatic reactions designed to convert glucose into two pyruvate molecules with energy production (2ATP+2NADH) in the cytoplasm. In order for the Krebs cycle to start, pyruvate needs to enter the mitochondrial matrix and, by the end of the cycle, there will be more metabolic energy (2ATP+8NADH++2FADH2). In the glycolysis and Krebs cycle pathways, energy carriers (NADH+ and FADH2) are derived so that they can be used in oxidative phosphorilation through mitochondrial complexes which play the role of electron mobilisers. This process starts when NADH+ oxidises to NAD+ and gives 2 electrons to complex I; these electrons are transported between complexes II, III, IV and arrive at the mitochondrial matrix in order to bind to an oxygen moiety and 2H+ to form water. Every time electrons travel across complexes, they pump H+ towards the mitochondrial inter-membrane space, creating a proton gradient in complexes I (4H+), III (4H+) and IV (2H+); this gradient is again transported towards the mitochondrial matrix through the ATP synthase complex in order to phosphorilate ADP and produce 4 ATP molecules, resulting in 38 ATPs during the entire cell respiration (2 ATPs are used as currency to initiate glycolysis). In short, the purpose of the three stages of cell respiration is to generate the necessary energy to maintain optimal cell metabolism19–22 (Fig. 1). When, for some reason, the aerobic pathway is not followed, the anaerobic pathway will be activated in order to produce energy. In cases of metformin overdosing, the drug binds to the mitochondrial membranes, specifically complex I, inhibiting the electron transport system (oxidative phosphorilation). When NADH is not oxidised, it accumulates, there is a change in the anaerobic mechanism with increased production of lactate, in an attempt to produce the necessary energy to maintain the physiological conditions of the cell. However, the level of energy is lower and only 4 ATP molecules are produced. Blood lactate accumulates, the SID is altered, and lactic acidosis ensues.

DiscussionMetformin is a small 165Da molecule with an oral availability of 55% and a distribution volume of 1–5L/kg. It is eliminated practically unchanged through the kidneys, and its total body clearance in subjects with healthy renal function is 500ml/min, 200ml/min with intermittent dialysis, and 50ml/min in patients on slow continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT). Therapeutic concentrations are 1.5–3.0mg/L. The elimination half-life is 8–20h in individuals with normal renal function.23–28

Outcomes will improve when risk factors for the development of lactic acidosis are recognised, including deterioration of kidney or liver function, alcoholism, reduced tissue perfusion due to infection, age over 60 years, and heart failure in patients receiving metformin-based treatment; also, early diagnosis and timely initiation of renal replacement therapy are critical for success.29,30 The vast majority of patients admitted to the ICU with metformin-related lactic acidosis are over 65 years of age and present with haemodynamic instability and acute renal injury.31 Intermittent or continuous renal replacement therapy with haemodiafiltration to eliminate metformin and lactate from the blood is recommended, the argument being the correlation between reduction of metformin plasma levels and improvement in lactic acidosis.32

Hypotension is treated initially with intravenous fluids, followed by the use of vasopressors if needed. For patients with metformin poisoning, extracorporeal haemodialysis is the preferred treatment as long as there is haemodynamic stability. Although there is limited evidence regarding slow CRRT, it is preferred in patients with haemodynamic instability because it is better tolerated than haemodialysis.33 The working group on extracorporeal treatments in poisoning (EXTRIP), comprised by international experts who represent different societies and specialties, makes recommendations in this regard. Extracorporeal treatment is recommended in severe metformin poisoning (1D), primarily if lactate is ≥15mmol/L, pH ≤7.0 and standard therapy (including NaHCO3−) has failed (1D), or in the presence of shock (use of vasopressors) or decline in kidney function (1D). Discontinuation of extracorporeal treatment is indicated when lactate levels are lower than 3mmol/L and pH is higher than 7.35 (1D). Intermittent haemodialysis will always be the first option (1D), although slow CRRT will be the preferred choice in presence of haemodynamic instability (1D).34 Compared to lactic acidosis of a different origin, metformin-related lactic acidosis is associated with lower mortality (50% vs 74%) and has a better prognosis, even when pH is under 7.0.35

On the other hand, treatment of any alteration in acid–base balance must be targeted to the underlying cause. Acidosis has a protective effect in anoxic or ischaemic cells, but that protection will be lost at a certain point, which is still a subject of controversy (pH under 7.2, HCO3− less than 10mEq or base deficit greater than −10mmol/L). Addressing acidosis could result in a paradoxical effect (“harm and no benefit”). Acidosis protection could be related to an enzyme “sparing” effect. Treatment of metabolic acidosis should be aimed at avoiding cell dysfunction occurring as a result of intracellular increase of Na+ and Ca2+ levels, driven by intra and extracellular pH alterations.36

The use of sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3−) is a controversial strategy that has not been fully validated in the clinical scenario of lactic acidosis and haemodynamic instability, regardless of the aetiology. This measure is considered a bridging therapy while waiting for aetiologic treatment. Even the international guidelines of the Surviving Sepsis campaign recommend the use of NaHCO3− when pH is less than or equal to 7.15 in order to improve the haemodynamic state or reduce the number of vasopressors in patients with hypoperfusion-induced lactic acidosis.37 A recent publication of a review study that evaluated the use of NaHCO3− in the treatment of lactic acidosis due to sepsis reported that the routine use of NaHCO3− continues to be controversial, and concluded that further studies are required in order to determine a potential benefit.38 NaHCO3− administration may give rise to side effects, including increased production of carbon dioxide(CO2) and reduced ionised calcium, which may contribute to diminished right ventricular contractility or vascular tone. Moreover, there is the potential for a paradoxical effect because of the improvement in extracellular pH but not so of the intracellular pH (intracellular hypercapnia).39

The use of NaHCO3− in the treatment of metabolic acidosis has been shown to have beneficial effects in diseases where there is evidence of HCO3− loss. In contrast, no benefit has been observed when it has been used to address metabolic acidosis from other causes.40 Additionally, the use of NaHCO3− has been proposed as a diagnostic method in the form of a bicarbonate challenge to determine the origin of metabolic acidosis, mainly in patients with septic shock and severe metabolic acidosis and high risk of hypoperfusion-associated complications such as hypoxic hepatitis, a condition that usually occurs after prolonged hypoperfusion, as well as inflammation, hypoxaemia and hypoxia. It would be wise to assume that prompt and accurate diagnosis of metabolic acidosis (hypoperfusion) will lead to early targeted treatment or help consider a different source (exogenous acid production) at an earlier stage, in order to modify the diagnostic and therapeutic approach.41

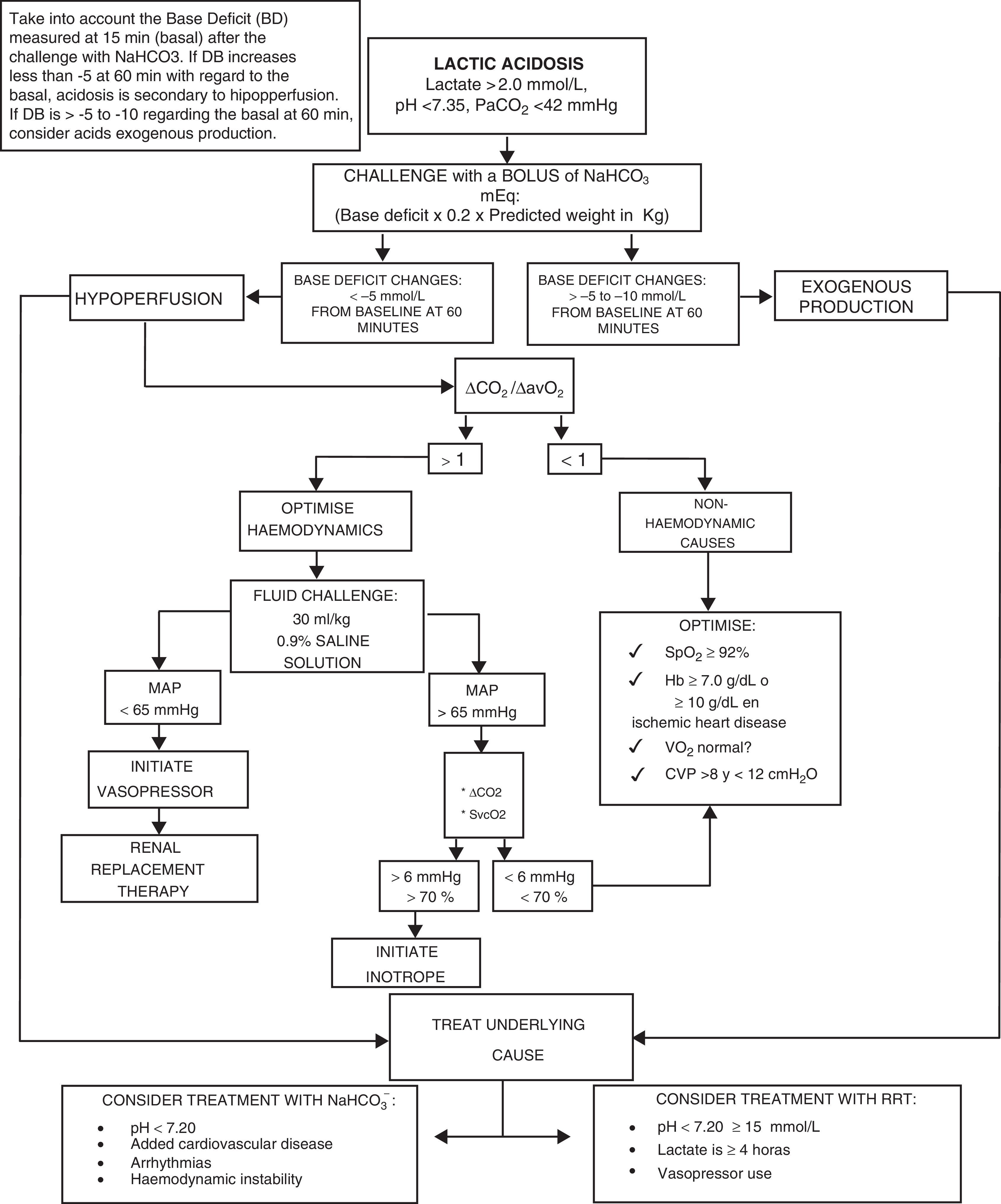

We present the management algorithm used in our critical care unit in cases of lactic acidosis (Fig. 2).

Algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of lactic acidosis.

NaHCO3−: sodium bicarbonate; pH: negative log of hydrogen ion concentrations; PaCO2: carbon dioxide arterial pressure; ΔCO2: carbon dioxide difference; ΔCO2/ΔavO2: carbon dioxide difference between arterio-venous oxygen difference; MAP: mean arterial pressure; SvcO2: central venous oxygen saturation; SpO2: peripheral oxygen saturation; Hb: haemoglobin; VO2: oxygen consumption; CVP: central venous pressure; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

Source: Author.

Lactic acidosis is common in critically ill patients and correlates with severity and prognosis. However, the aetiology of lactic acidosis is a key determining factor for outcome. Timely diagnosis of the mechanism and cause of lactic acidosis will favour early targeted treatment. Treatment success depends on the control of the aetiologic source. Metformin-related lactic acidosis has a better prognosis lactic acidosis induced by septic shock. Intermittent or continuous renal replacement therapy should be used as the first step in the treatment of metformin-related lactic acidosis.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

FundingThe authors were not sponsored to carry out this article

Conflict of interestThe authors declare not having received external funding for this research and not having conflict of interest regarding publication.

We thank the medical and nursing team on the different work schedules in the intensive care unit who collaborated in the comprehensive care.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Díaz JS, Monares-Zepeda E, Martínez-Rodríguez EA, Cortés-Román JS, Torres-Aguilar O, Peniche-Moguel KG, et al. Acidosis láctica por metformina: reporte de caso. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2017;45:353–359.