To recognise the changes experienced by the therapist who works with gay and lesbian couples.

MethodQualitative with biographical-narrative method. Seven therapists were interviewed in Medellin.

ResultsThree moments in the life trajectory of the participants were identified: Before: closeness and distances between families and the school were found (distances, makes reference, among others, to discourses about homosexuality). During: showed the conspiracy of silence in the undergraduate and postgraduate training of therapists, and in the clinical approach with homosexual couples they perceive in the reasons for consultation, a spectrum between everyday conflict and imposed exclusion. After: makes reference to the changes that this clinical work has generated in them, how they have become different, while others have been defined as: political subjects who resist normalisation and become learners of artistic territories and artisans of their own lives.

ConclusionsThe task of becoming another is a poetic, aesthetic and ethical process like the beautiful creation of the own existence. These transformations are connected with presence, social, politic and artistic contexts, reflexive labour and criticism about themselves.

Reconocer las transformaciones que han tenido los terapeutas a partir de la atención a parejas lesbianas y gais.

MétodoEnfoque cualitativo con método biográfico narrativo. Se realizaron entrevistas a siete terapeutas de la ciudad de Medellín.

ResultadosSe identificaron tres momentos en la trayectoria de vida de los participantes: el antes, donde se encontraron cercanías y distancias en relación con sus familias de origen y la escuela (las distancias hacen referencia, entre otros, a los discursos sobre la homosexualidad); el durante, que evidenció el complot del silencio en la formación de pregrado y posgrado de los terapeutas y en el abordaje clínico con las parejas homosexuales que perciben en los motivos de consulta, un abanico que oscila entre el conflicto cotidiano y la exclusión impuesta; el después, que hace referencia a las transformaciones que dicha labour clínica ha generado en ellos, cómo van siendo diferentes en tanto han ido deviniendo otros como sujetos políticos que se resisten a la normalización y se hacen aprendices de territorios artísticos y artesanos de la propia vida.

ConclusionesLa labour de devenir otro es un proceso poético, estético y ético en tanto creación bella de la propia existencia. Estas transformaciones se vinculan con presencias, contextos sociales, políticos, artísticos, labour reflexiva y crítica sobre sí mismo.

Historically, lesbians and gays have been discriminated against as a subculture removed from the family nucleus because they have been viewed as more sexual than social beings.1 They have been portrayed as eternal singles, going from one relationship to another. Until the 20th century, this condition was even classified as mental illness.2,3 Until the 1980s, homosexuality was a crime included in the Colombian penal code, punishable by imprisonment.4,5

However, the recent Colombian policy of Sexuality, Sexual and Reproductive Rights 2014–20216 advocates prevention of any form of discrimination or stigma of non-heterosexual forms. The law focuses on rights and creates mechanisms for people to exercise and demand their rights to overcome inequality and live their sexuality more fully. In terms of legislation, significant progress was made from 1991 to 20007 in terms of educational, labour and patrimonial rights and health inclusion. However, in relation to the recognition of homosexual families and adoption, there have been historical obstacles based on the heterosexist practices and discourses of the Catholic Church and moralist and conservative sectors of society, among others. Against that kind of pressure, the Constitutional Court encourages progress while Congress refrains from legislating.8

In agreement with some court proceedings in Colombia relating to this subject, in 2003 the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Catholic Faith considered that homosexual unions went against the natural law.

It must be pointed out that political, social, medical, legal and religious discourse has, throughout history, conducted a campaign of antipathy, condemnation, aversion, fear and proscription of homosexual behaviour that, according to a term coined in 1960, can be defined as homophobia.3,5,9 One of the bases of this fear is to think that homosexuality disrupts the sexual and gender order and alters the natural, social, political, legal, ethical and moral order of society. Homophobia has close ties to other forms of social exclusion such as racism and anti-Semitism. To nurture these messages and ensure they remain socially active, a particular stereotype is cultivated that circulates in the social world and keeps these minorities excluded. Homophobia is much stronger with gay men, who are despised for acting like women. Throughout history there has been more tolerance towards lesbians; until recent times lesbianism was almost invisible. This may have to do with the lack of visibility traditionally experienced by women in general.9

Family therapy, psychiatry and mental health professionals have not been immune to these messages, as demonstrated by research and the teaching and training of researchers, teachers, students and therapists. According to a study by Clark et al.,10 articles on same-sex couples published in couple and family journals between 1975 and 1995 accounted for less than 0.006%. Research on homosexuality in the 1980s prioritised the conversion of homosexual identity into heterosexual identity. In 1996, a study conducted with 526 members of the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy showed that about 50% of them did not feel competent to work with lesbians and gay men. In the therapeutic field, discriminatory practices such as conversion therapies are currently being performed in order to “repair” this “disorder”.11 Some psychiatrists still consider homosexuality as a disease and associate it with comorbidities such as obsessive-compulsive disorder or personality disorders.5

Despite these obstacles, there is no doubt that there has been a slow but significant shift in the attitudes of mental health professionals. Among other reasons, this has probably to do with the social protest movements and political activism of the homosexual community in the 1970s, as well as the decision of the American Psychiatric Association and WHO to remove homosexuality from the list of mental illnesses, and the publication of research and scientific articles.

In clinical work with gay and lesbian couples, some studies have shown that their demand for therapy has increased; some 25–77% of them have used it. It is reported that lesbians are more positive about psychotherapy and are better at continuing therapy than heterosexual women.12,13 Many studies have shown that the level of knowledge about lesbians and gay men and the degree of contact with them have an impact on positive therapeutic attitudes with this population.3,12,13

In terms of the therapeutic approach for homosexual couples, some studies show the similarities and differences with heterosexual couples and the lack of preparation in the field in therapist training.12,14 Other studies determined the levels of homophobia, and found it to be as endemic among healthcare workers as it is in society as a whole.13,15,16 We found no studies, either local, national or international, acknowledging the transformations in therapists brought about by their clinical experience with homosexual couples.

Outline of the studyThe study was conducted by researchers from the Family and Mental Health section of the Psychiatry Research Group at Universidad de Antioquia. The approach was qualitative: it investigated the therapists’ experiences and the changes they were aware of in themselves after dealing with homosexual couples.17 The method was biographical narrative.

For Ricoeur,18 life is narrated, represented and transformed, revealing its identity. The study analysed the personal and socio-professional circles of the subject of the biography. In the narrative, the participants visualised events that made it possible, based on the joint interpretation of the interviewee and the researchers, to introduce science into life.19

The biographical interview was used to learn the life stories in order to create meaning between the interviewee and the researcher as the process developed.

The units of analysis were: the narratives that seven therapists from Medellín gave about clinical interventions with homosexual couples. Two interviews were conducted with each therapist.

The analysis of the narratives sought to discover the essential and to differentiate the relevant from the accessory by refining the data obtained in the interviews.

Reading the narratives: the interviews were recorded and later transcribed and read with the aim of:

- •

Identifying the events in the stories related to the transformations that occurred in the therapist.

- •

Making the events that were related to the transformation visible.

- •

Subsequently selecting texts and putting them together.

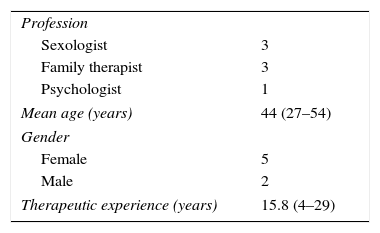

The participants (Table 1) had homosexual subjects, couples and families among their clients. Three of them worked in private practice and the other four practiced both privately and for public institutions (Table 2).

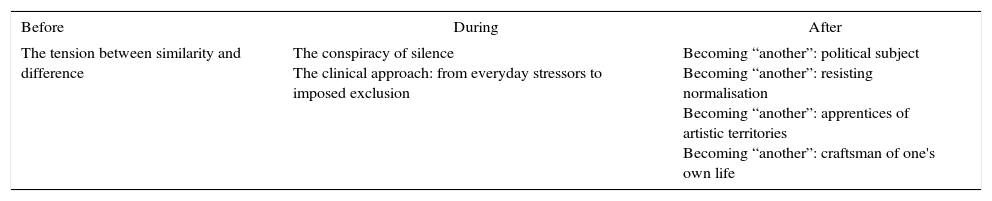

Biographical trajectories of the participants.

| Before | During | After |

|---|---|---|

| The tension between similarity and difference | The conspiracy of silence The clinical approach: from everyday stressors to imposed exclusion | Becoming “another”: political subject Becoming “another”: resisting normalisation Becoming “another”: apprentices of artistic territories Becoming “another”: craftsman of one's own life |

The stories of each of the seven therapists were very valuable, helping the researchers to see beauty, pain and exclusion, thus transforming them into “another”. To maintain the participants’ confidentiality, names of precious and semi-precious stones were used instead of their real names: Ruby, Onyx, Sapphire, Diamond, Pearl, Emerald and Quartz. Their biographical accounts were organised into three moments:

- •

The “before”: in which their experiences with their families of origin and their peers converged up to the time they started university.

- •

The “during”: experiences while training as undergraduate and postgraduate students and from their early clinical practice.

- •

The “after”: showed the transformations, evolution, that had been gestating in the therapists’ current life.

Every moment of their life's trajectory was nourished by aspects that allowed for the ongoing transformation experience to come to the surface.

The “before”: the tension between similarity and differenceMost of the participating therapists described their families as very traditional, with differentiated gender roles and an emphasis on the culture of values, exemplified in respect, study, work, responsibility, sport and study, which permeated them: ... My dad was a lovely, conservative man; my mum, a normal housewife, a very loving woman, very motherly... A very academic family (Emerald, I1). My family was very traditional; my mother acting as tutor/instructor; my dad with the role of provider and worker; mum laid down the law... They demanded a lot of me, giving me responsibilities since I was little (Quartz, I2). I was raised with values like respect for human beings, honesty, responsibility, commitment, for our actions as human beings (Ruby, I1).

In relation to discussion about homosexuality, both at school and in family life, this was completely forbidden. What little was said on the subject was said in a tone of mockery, aggressiveness and, in some, worry about it being contagious. ... When I was little I don’t remember hearing anything about homosexuality, a little at school, very conservative... Of course there was one guy at school, when he turned 15, I remember the comments that he was a poof, in those derogatory terms people use. I heard about it that way (Emerald, I1). It was never talked about at school; I went to a religious school... I was older, had a nephew who was effeminate, so in my family, which is macho, there were aggressive comments towards him (Pearl, I1).

Faced with these family and social positions in relation to homosexuality, some of the participants described themselves as distanced from such talk, as rebels who were able to think differently or not believe: I think I’ve always been very rebellious, I was a rebel and I didn’t believe, or I clashed with those ideas (Emerald, I1).

They also explain how they distanced themselves on having been born in the middle of important social movements, having had different experiences. ... I was born in ‘69, after May ‘68. I was born in a time of revolutions, so despite coming from a very traditional family, rosaries, mass, I have always had more revolutionary religious beliefs: my beliefs and practices are of the Jesus of the Gospel, a loving Jesus (Pearl, I1). Catholicism is deeply ingrained in my family history; nevertheless, the times, my age, my personal experiences put me more in the category of open-minded religious beliefs (Quartz, I1).

In the “before”, the tension between similarity and difference became evident in the way in which therapists remained close, faithful to family values they experienced as opposed to studying, responsibility and work, and how they distanced themselves in relation to the discourses about homosexuality or certain practices and beliefs and assumed a critical, reflexive position, with which they managed to connect how machismo and tradition can explain these discourses. They talked about what was setting them apart from their families as they described themselves as rebels, open to experiences and contextualised by the times in which they were born; these three elements that highlight intimacy, intersubjectivity and social life make it possible for them to configure and reconfigure, as Ricoeur puts it, “while weaving a plot between the concordant (the normative aspects of family experience) and the discordant (the event, that which breaks the pattern, the non-normative, the crises). Emplotting or weaving in intrigue makes it possible to synthesise the heterogeneous and include it in the story told, narrated”.20 They, by weaving their narrative plots, are reconfiguring their lives, those of their families and others in their social world.

The discourses found in their families of origin are consistent with what other research has found in relation to the practices of silencing and prejudice towards homosexuality, which are usually evident in people with conservative and right-wing political ideas, who regularly attend religious worship or who have negative attitudes towards women and a strong adherence to the hegemonic model of masculinity and the division of gender roles.21,22

In concordance with the above and with what was reported by the study participants regarding the silencing or marginalisation of sexual diversity, in Antioquia, Bustamante4 shows that in the 20th century these discourses were governed by the Christian perception of the world; morality was a matter for the Church and the family, where each gender had its defined place, in which homosexuals did not fit. For that reason homosexuality was hushed up, to avoid risking the breakdown of the conventional family structure and its main function.

The “during”: the conspiracy of silenceFor most of the therapists, from when they were at school and later as undergraduate and postgraduate students, there was a continuum of not talking about homosexuality. For some, the silence even extended to aspects of sexuality like contraception. ... But in medical school, we were never given the class as a disease, nor did we study transsexual gender dysphoria. They didn’t tell us anything. They gave the class on contraception in secret (Onyx, I2). As an undergraduate absolutely nothing... Practically, the ideas of psychoanalysis, the perversion of the father and the like were considered as something really mixed up (Emerald I1). As a postgraduate I didn’t receive any training in seminars or interventions related to homosexuality (Quartz, I2). Zero, nothing, because you couldn’t touch the subject. Not because it was taboo, but because it wasn’t seen as a social phenomenon (Sapphire I1). As an undergraduate and a postgraduate I received very little training... I think it wasn’t just because they didn’t know, which was the explanation they always gave me, but that no one had studied it – I think that was due to a structure and collective resistance to looking at diversity (Diamond, I1).

In this study, this hushing up of the “condition” of homosexuality is referred to as the conspiracy of silence. The word “conspiracy” refers to a conspiracy of a political or social nature or the confabulation of some people against others, which coincides with the experience the study participants had in not talking about homosexuality. This conspiracy of silence can be explained through the participants as:

- •

Denial of the reality through silence.

- •

A form of social resistance to including diversity.

These explanations that take shape in the silence are forms of discrimination and domination of homosexual minorities, exercised by the heterosexual majorities. Moreover, they are an expression of the fears that move within those institutions in relation to the subject; not mentioning it means you can pretend it does not exist, but mention it, and you allow it to enter the social world.

Faced with these forms of domination, minorities stir up forms of resistance. The social silence also provokes silence and concealment of the “condition” in them in order to protect themselves. They take advantage of the night as a form of transgression, as a device to express their homosexuality.4

That silencing, which emerged in this study, is consistent with Foucault's view23: in the 16th and 17th centuries sexuality was mentioned as little as possible in primary schools, seminaries and secondary schools. He identified this situation as a form of control of sexuality that can extinguish the verbal fires that the word can arouse in relation to desire and pleasure.

The lack of training that the participants talk about in relation to homosexuality is corroborated in other studies,12,13,24 which also show the scant literature and research related to sexual diversity to date. The fact that therapists do not acquire clinical competences for looking after these subjects and couples during their training is of concern, as there has been a growth in attendance by diverse subjects,13 and the professionals’ lack of knowledge can hinder their approach to their clients’ specific problems.

The clinical approach: from everyday stressors to imposed exclusionOn the basis of their clinical work with female and male homosexual couples, the participants have gradually come to realise how their conflicts are shaped by a continuum that goes from the everyday stressors, which are the same as those faced by heterosexual couples, to the particular, which refers to the discrimination to which they are party. ... The thing is that much of the problem is not because they are a homosexual couple, but because they are a couple. It's that simple. What I mean is that they face the same difficulties, tensions, maybe a touch extra for discrimination or marginalisation, but they face exactly the same problems, they face the same tensions. But I have also witnessed self-healing, self-repairing mechanisms which the couple has and that they can use; in the end, all one has to do is activate them (Diamond, I1).

This is why their reasons for consulting, just like heterosexual couples, are human suffering. ... There are couples who have consulted me because of infidelity, couples who have consulted me for communication problems, because they fight a lot. I would say that the reasons for consulting are problems that human beings suffer whether homosexual or heterosexual, there's not much difference (Pearl, I1).

The reason for consulting has nothing to do with being homosexual, but with the intrinsic dynamics of being a couple; what is happening to them is happening to a certain extent because they are a couple (Ruby, I2).

Given this similarity, according to the therapists, the type of support is going to be similar to what they do with heterosexual couples. My feeling, my thoughts when I worked with them was that I did the same as what I might do with another couple when they were a man and a woman (Quartz, I1).

But in clinical conversation, therapists have also perceived differences in relation to heterosexual couples. They refer to greater ease and openness for talking about sexuality, or to conditions of concealment of their lifestyle that have to do with the other end of the spectrum, i.e., the exclusion imposed socially for these couples, and which drives them to conceal who they are by being part of a family, becoming an individual, doing a job that prohibits, limits, conditions and thus leads these couples to seek therapy. ... Their experience of sexuality, which they even spoke about with an ease that I didn’t find with other heterosexual couples; they were more open to talking about it... Another thing though is when you touch on aspects that have to do with their social life, which is different from heterosexual couples. For these aspects there was concealment, they didn’t disclose their relationship in certain places; in certain places it was something forbidden (Quartz, I1).

They could not live together because the elder cared for her mother, who was very old, very sick and absolutely prohibitive of her daughter's sexuality (Quartz, I1). … One very important thing, I had already come out of the closet whereas he had not been able to come out; the anonymity, family resistance, work, the issue comes up a lot (Sapphire I1).

These couples may be faced with the fear of being discriminated against by therapists or they may discriminate against themselves, a situation that heterosexual couples do not experience. She told me from the start that it was “couple therapy”. When she was about to hang up, she said, “I want to ask you something, do you have any problem with seeing a lesbian couple? “That struck me, and I thought,” She felt she had to ask because she was afraid that someone would say that they wouldn’t see her” (Quartz, I2).

Exclusion, as already mentioned, can include the therapist or, as Diamond says, the health team which, like the rest of society, do not escape heterosexist socialisation and can let their prejudices and fears interfere with their delivery of care. It's surprising, many times I regret what I have seen other colleagues do – a homosexual couple arrives and from the first consultation they all come out with HIV serology, all that stuff, and I say, “Great! Very vigilant, it's logical, congratulations”, but if a heterosexual couple comes in, do they do the same? No, they don’t even ask for a creatinine test or a blood count (Diamond, I2).

Including particularities that these couples experience that heterosexual couples do not, given the marginalisation and discrimination they have lived through, it means helping to deconstruct the prejudices against homosexuality that have been woven throughout history as causes of disease, which often circulate in our clients’ stories. … It's what one should say: your erectile dysfunction is just the same as what could happen to any heterosexual man; so, it is partly reparative; it's not because I masturbated a lot as a teenager thinking of a man – no, don’t worry; it's not because I had previously had sex with lots of men – no, no, no, don’t worry, nothing happened, because you don’t have any infections or anything, you’re fine, nothing like that has happened (Diamond, I2).

It also means becoming a reader of the couple's life to avoid prefiguring it or considering it according to heterosexual or stereotypical rules. What do you aspire to? What kind of a couple do you want to be? Because maybe it is not the mould that you have always been shown. You are instead exploring possibilities in areas where nothing is established or predetermined or preconfigured, and if I support you in that process, I have to say, “I won’t put you in the mould I already have for you, which they taught me and with which I got 5/5 in a postgraduate essay; instead, you show me. I’ll begin there. I’m a great reader” (Diamond, I2).

The clinical approach: it is what the participants call the emergence of a continuum in their approach towards these couples, from the everyday stressors to the imposed exclusion. This accounts for how the concerns they have and approaches they use in their clinical work involve a process of discovery in listening to what they are going through in their daily lives, just like heterosexual couples, with a mixture of conflicts such as difficulty communicating, jealousy, infidelity, ageing, rage. These everyday stressors, which sometimes lead to consultation for therapy, make it possible, as one of the therapists said, to recognise the humanity that also inhabits them, thus blurring the nosological and psychopathic or dysfunctional ideas that have so often stigmatised homosexuality.

The researchers consider as a hypothesis the fact that the therapists see the everyday stressors as a common cause of consultation and implement an approach that coincides with that used with heterosexual couples to be precisely because of the naturalisation of the participants’ attitudes towards homosexuality.

This continuum is not to deny the imposed exclusion that they have experienced and which can at times be part of or be the motivation to seek therapy. The imposed exclusions that emerge from the participants’ accounts are referred to in this study as hetero-imposed and self-imposed. The former arise from their relationship with others; from the healthcare team, society, family, work environment. The latter emerge from themselves. These forms of hetero-exclusion/self-exclusion, which have been imposed on homosexual subjects throughout history, necessarily cause them pain that heterosexual couples do not go through, which places on them, their partners and their families additional burdens on top of life's everyday stressors.

As for what has been called “the clinical approach: from everyday stressors to imposed exclusion” in this study, other studies10,14,16 have also found that female and male homosexual couples consult for similar situations as heterosexual couples, but that they have particularities which, as found in our study, have to do with social and individual factors that call for concealment due to social stigma and self-stigma. Consequently, they involve the need to work on their own and external stigmatisation in therapy.9

In relation to the exclusion imposed by the healthcare team reported by the therapists, several studies have found that homophobia is an endemic attitude in health workers,16 as in society in general. De la Espriella5 reports how some suffer from this condition but do not externalise it because it would be received negatively in the social environment.

With regard to therapists, some authors13,25 have stated that they do not escape socially shared heterosexist prejudices and can impose these stereotypes, or ignore the subjective particularities of homosexual couples, and impose ways of being a couple in the dominant heterosexual perspective.

As regards the self-exclusion that can be exercised by female or male homosexual individuals, as can be interpreted from an account by one of our participants, Carter et al.2 report that self-exclusion can be linked to the fact that they have been socialised in a heterosexist/homosexual biculture, which does not free them from prejudices that circulate socially in relation to homosexuality. Some have called this situation internalised homophobia, referring to the process by which a subject who forms part of a stigmatised group internalises the negative stereotypes and the expectations of the majority.10

AfterBecoming “another”: political subjectTheir work with homosexual couples has awakened sensitivity for their humanity in the participants, inspiring the need for reflection and political commitment to talk about homosexuality as a right that deserves to be de-demonised and established as a lifestyle choice. … Also to consider being more decisive on this subject, to have... a one-off political activism (Quartz, I1). … After hearing about all this suffering and listening also to all the beauty that these people have inside, a pain that is purely irrational, absurd, I believe that the transformation in me was the need to talk more about it. I would call it a political exercise (Pearl, I1). … Sensitivity, to see the human being, it seems to me, and I say it in my talks a lot and it's in the sexual rights charter, that one has the right to have any identity or any generic preference... to de-demonise the subject, the “it's a sin”, “an aberration”. It's a lifestyle choice (Onyx, I2).

This political commitment has had different scenarios: teacher training, educational support for children by NGOs, inclusion in the training of healthcare professionals and at conferences.

I had worked a lot training professionals and people in Antioquia, but when I got to Guajira that was something else... I had to help because societies really need to open up... They were teachers. I really noticed in education how close-minded they were (Emerald, I1). … They see sexuality, genitality, connoting it with violence... because many were abused in their childhood; we are a project that prevents, we are talking about teaching, but that is articulated with the NGO (Sapphire I2). ... I had to talk about it. It was an ethical obligation. I couldn’t continue with that silence or with aggression associated with that subject. In the curriculum there has to be a seminar on homosexual couples... I have touched on the subject a couple of times in public settings. These are my political challenges, to give aesthetic existence to homosexuality (Pearl, I1).

From the Foucauldian perspective, resistance26 involves questioning the mechanisms of power and their dispossession from their excess moral and legal burdens.

The study participants are resistant to dominant discourses regarding homosexuality, insofar as they consider that it is not a matter of illness or health, abnormality or normality; it is a nature that transcends the positivist polarities in which it is proposed to understand life. So, everything is normal, right? It's not that it is normal or abnormal. There are some very clearly established guidelines, but there are others that are very rigid and do not allow us to see a being as such... We cannot continue to see it as an illness. We are violating a right when we judge by generic preference (Onyx, I2).

According to one participant, the heterosexual standard forms in which we are to perceive homosexuality interfere with our understanding of this diverse nature, but they are not definitive. The environment in which we develop, where we grow up, interferes in the development of how we think about homosexuality, but it is not absolute, it is not determinative (Ruby, I1).

And they are not because the subject can question, resist, criticise the mechanisms of power from which the discourses of normality-abnormality emerge. Who really has the power to judge? Who decides what is morally right? From what paradigm? (Quartz, I1)

By resisting, the therapists are able to include, and thus strive to integrate, the plurality of the human experience.

Becoming “another”: apprentices of artistic territoriesIn their attitudes towards female and male homosexuality, the therapists were part of the conspiracy of silence, and so in their family and academic lives, this prevented them from knowing anything about the lives of these subjects. In some cases, they call themselves apprentices who were entering artistic territories, such as the cinema, theatre or literature, to take a closer interest in this experience, to use them as devices for learning. Studying psychology, that was my first educational device; experience forms theory. Cinema was what began to educate me in what I call gender theory or in the theory of sexual and gender identities... Cinema is a reflection of our reality (Sapphire, I1). I’m an apprentice. I need to know more about the lives of these people. So, many years ago, I started going to a Pink Film Season at Centro Colombo Americano. Seeing the suffering of these people who had AIDS, seeing the care networks with the chosen families, with the homosexual community or with heterosexuals, that was very important for me; their humanity, suffering and discrimination made me well up (Pearl, I1).

The everyday life of subjects, their humanity, their universality as the subject of pathos, emerges in art. To have the scene set and see one's own and other people's pain, the combativeness and the networks of life through the theatre, literature, dance or the cinema, is a source that enables the opening up of pathways to the subject of homosexuality, in terms of saying what couldn’t be said. My big moment of contact was also through the theatre. Lately my source (I have been seeking it out) has been in the theatre; the performativity of the theatre, which I believe is what is reproduced in things, too (Diamond, I1).

In classical literature, in cinema, in dance, you can express what the human being is not allowed to say. It is an expression of life, of what happens in the world... It is universal. It allows me to see things that I feel, that I see, that I hear (Ruby I2).

Becoming “another”: craftsman of one's own lifeIn listening to the clients, the therapists, like the craftsmen with their work, are taking on new forms themselves and are also proposing alternative forms, with less suffering, for the clients, and with this coming and going, words and encounters gradually transform them. Therapists are transformed. It's the beauty of this work. You become what or who you work with. It's like the craftsman's trade: their hands become transformed by the craft; he who tills the earth opens his hands to work the earth. The same thing happens to the therapist with the couples; by cultivating the couples, they too open their hands, and, I hope, also think critically in themselves (Diamond, I1).

The craftwork that the therapists do on themselves involves learning processes and breaking paradigms and models to learn how to weave different ones; this work is nourished by the encounter in therapy with same sex couples. Since I began to break paradigms and smash models, my mentality has changed. This has lead to an enriching transformation as a therapist. By providing support to same sex couples, I am educating myself. The stories and these constructions are very, very different realities that are expressed with feelings that break with the established order. I have transformed my mentality, or that is, this vision of conscience... (Sapphire, I1)

But the craftwork is not limited to their intimate self, but also emerges in their private life with their own family, where, according to the study participants, they openly and respectfully talk about sexual diversity; they talk, although some families more openly than others, but they talk, and that raises awareness, it transforms. I have always talked about it openly. What I mean is that my family know that this is how I think and that I do so openly. For example, I‘ve had conversations with my daughters and my nephews. In my family I don’t keep quiet. In my family of origin it's a subject that provokes argument, but in my immediate family, i.e., with my daughters, I believe that I have raised their awareness (Emerald, I1). It's talked about very openly at home in terms of us as a couple, to validate, to respect... In fact, my daughter has a lovely friend, aged 16, and she says he is gay, and he's her friend. We have lived that experience openly (Quartz, I2).

The craftwork therapists do on their own lives and those of their ancestors and descendants leaves trails. That they can speak to their descendants about sexual diversity, and that their descendants can be open and maintain friendships with their different peers, is evidence of the craftsman's work being woven and amplified.

The elements that stand out in the life of the subjects interviewed reveal the processes of transformation we have called “becoming” in this study. This becoming “another” in the political, clinical, theoretical and existential dimensions seems to be in line with the therapists’ reports. It is not a situation that has emerged from clinical work with male and female homosexual couples, but rather it is present—as was related in the “before”—in their distancing from the established order; lines of flight from the hegemonic discourses and acts of language with which they have lived.

This becoming “another” has allowed them to mutate, to transform themselves throughout life, leading them to move fluidly, not fixedly rooted in the territory of a certain belief or religion. Instead, it has enabled them to become a polyphony or, according to Deleuze,27,28 it is transforming or evolving them from molar lines to molecular lines. Molar lines are hard lines. It is the majority becoming the aspiration of most people that makes it possible to access a certain position of domination. These lines refer to the binary categories that govern society: man–woman, black–white, heterosexual–homosexual. Molecular lines are smaller intensities experienced by minorities, which do not represent the binary, but instead the desire to flee, to become territories alternative to the molar, to transform the paradigms in which subjectivation had been organised.

This becoming, i.e., this deterritorialisation, is the line of escape present throughout their lives. As subjects of action, they make it possible to mutate and resist suffocating lines of power in order to trace new narratives of greater movement.29

The condition of deterritorialising oneself, i.e., distancing oneself from the molar lines of their context and their subsequent decision to dedicate themselves to therapy, is linked to what some authors30 have suggested: that becoming a therapist is closely linked to a desire for rebellion, a desire to question tradition in some way.

Consistent with what emerged in our study participants, regarding subjects who are deterritorialised, i.e., who are transformed, Le Blanc31 refers to how normal everyday life is potentially explosive because the subjects do not stop moving, deploying potential, which he calls trembling. They, as political subjects, who resist normalisation, craftsmen of their own lives, do not submit to the norms of the majorities, rather they take a risk on novel forms that make them speak in public and private spaces with respect and inclusion of sexual diversity.

These new forms that are being created are going to be discovered by apprentices and not experts. These apprentices need to be nourished in different situations to enable them to reach intimate, private and public spaces to become “another” and to encourage others to also become “another”. These tremors that are occurring in the therapists and in the private and public spheres through which they travel show the creative potential that inhabits them and the transformations that take place in ordinary life.

The therapists in this study question, reflect, resist, create, speak and act. In other words, they deviate from the norms, powers and laws of heterosexist culture. This is consistent with what Le Blanc proposes when he states that the subject of ordinary life, more than opposing the established order, can deviate its subjective course by prioritising a poetic capacity which Certeau calls “the art of poaching”, i.e., the art of hunters who succeed in transforming adversity to their own advantage.

Becoming “another”, creating trembling forms in everyday life, makes it possible to crush existing norms, diverting them to micronorms that respond to subjective desires, to new transformations that are free from pain and exclusion.

ConclusionsThis study has referred to the biographical transformations of seven therapists who participated by sharing their life and professional experiences providing therapy to lesbian and gay couples. In their life trajectory, it was possible to show that the transformations that were taking place did not develop the moment they began to support these subjects. Instead, they emerged from the “before” and the “during”, in other words, from their childhood, youth and adulthood. This transformation had its origins in personal processes of reflection and criticism, in encountering others and in their distancing from family and social discourses, which made it possible to capture differences and integrate aesthetics and sufferings of different subjects.

These transformations, called becoming “another”, have led them to become political subjects who are resistant to normalisation, and they see themselves as apprentices and craftsmen of their own lives. In this process of becoming “another”, they are demonstrating poetic, aesthetic and ethical forms as creators and craftsmen of beautiful ways of becoming subjects of action and discourse in their intimate, private and public spheres. These forms that are being created have been making it possible for them to integrate the plurality of human life, liberate them from exclusion and the fear of the different other, giving them new ways to deterritorialise themselves from the molar lines of their ancestry to molecular lines of minorities. They become “another” while in their life trajectories they move from one territory to another. In other words, they are reterritorialising, i.e., creating with other multiple forms of living that surpass the Cartesian dichotomies.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

To the therapists who participated in the research for their generosity in sharing their experiences and life trajectories with us. To the University of Antioquia for its support.

Please cite this article as: Builes Correa MV, Anderson Gómez MT, Arango Arbeláez BH. Devenir otro: transformaciones del terapeuta que atiende a parejas lesbianas y gais. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2017;46:12–21.

This research was presented at the 9th International Public Health Conference: development, visions and alternatives, held in Medellín, Colombia from 19 to 21 August 2015.