Diabetes is one of the main pandemics in recent years. Its association with depression increases the risk of mortality and morbidity. The coexistence of both diseases leads to poor management of diabetes, which leads to a worse quality of life.

ObjectiveTo determine the frequency of depression in patients with diabetes mellitus and the effect of both pathologies on the quality of life in patients who attend outpatient appointments at public health facilities in Lima and Callao.

MethodologySecondary analysis of the Epidemiological Study of Mental Health of depression in diabetic adults. The instrument used to determine the depressive episode was the MINI (Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview) while quality of life was measured using the Mezzich Quality of Life Index. Diagnosis information of type 1 or 2 diabetes was obtained from the daily medical record (HIS) of care.

ResultsThe frequency of depression in the 471 patients with diabetes was 5.8% in the last two weeks. While the annual frequency was 8.6% and 31.8% at some point in life. Being a woman was associated with a greater frequency of depression. Quality of life was lower in patients with diabetes and depression (p < 0.005).

ConclusionsThe frequency of depression in patients with diabetes who are treated on an outpatient basis in public health centres is higher than the general population and their quality of life is significantly reduced, which raises the need for considering depression as an additional factor to the burden of morbidity of this condition.

La diabetes es una de las principales pandemias en los últimos años. Su asociación con depresión incrementa el riesgo de mortalidad y morbilidad. La coexistencia de ambas patologías produce un mal manejo de la diabetes, lo que conlleva a una peor calidad de vida.

ObjetivoDeterminar la frecuencia de depresión en pacientes con diabetes mellitus y el efecto que tienen ambas patologías sobre la calidad de vida en pacientes que acuden de forma ambulatoria a establecimientos de salud públicos de Lima y Callao.

MétodosAnálisis secundario de la base de datos del Estudio Epidemiológico de Salud Mental de depresión en adultos diabéticos. El instrumento empleado para determinar el episodio depresivo fue el MINI (Entrevista Neuropsiquiátrica Internacional) mientras que la calidad de vida fue medida empleando el Índice de Calidad de Vida de Mezzich. Se obtuvo información de diagnóstico de diabetes tipo 1 ó 2 del registro médico diario (HIS) de atención.

ResultadosLa frecuencia de depresión en los 471 pacientes con diabetes fue 5.8% en las últimas dos semanas. Mientras que la frecuencia anual fue 8.6% y en algún momento de la vida 31.8%. Ser mujer se asoció con mayor frecuencia de depresión. La calidad de vida fue menor en los pacientes con diabetes y depresión (p < 0.005).

ConclusionesLa frecuencia de depresión en pacientes con diabetes que son atendidos en forma ambulatoria en centros de salud públicos es mayor a la población general y su calidad de vida se ve reducida significativamente, lo que plantea la necesidad de considerar la depresión como un factor aditivo a la carga de morbilidad de esta condición.

Diabetes is one of the most prevalent diseases in the world, and it is on the rise worldwide, especially in middle-income countries like Peru. It is becoming one of the main pandemics today, with more than 420 million people suffering from it per year.1 In addition, diabetes presents a high degree of comorbidity, not only with cardiovascular problems derived from the pathophysiological complications of the disease itself, but also with other problems such as Parkinson's disease, schizophrenia and depression.2 Moreover, the risk of mortality and morbidity increases as it is associated with other pathologies, depression being one of them,3 affecting adherence, functioning, and treatment costs.4 The relationship between depression and chronic diseases, including diabetes, has been established in a two-way relationship where psychosocial factors associated with depression affect medical conditions and, in turn, the impact of chronic diseases can predispose to depression. Depression is one of the illnesses with the highest burden of morbidity in the world and is a priority public health problem.

Various studies in developed countries have shown that patients with diabetes have twice the risk of developing depression compared to non-diabetic groups.5 Moreover, the course of depression is longer in those with diabetes mellitus than in the general population.6 In all, 64% of people with diabetes have depression with a relapsing-remitting course, 15% never recover from their depression and only about 20% fully recover.7,8 The Medical Outcomes Study showed that the coexistence of chronic diseases with depression has an added impact on the functioning of the person who suffers from it.9 There are few studies on the frequency and prevalence of depression in patients with diabetes in developing countries.

MethodsThis study was a cross-sectional study based on the secondary analysis of the database of the “Estudio de Salud Integral en Hospitales Generales y Centros de Salud de Lima Metropolitana y el Callao-2015” [Comprehensive Health Study in General Hospitals and Health Centres of Metropolitan Lima and Callao-2015] carried out by the Honorio Delgado-Hideyo Noguchi Instituto Nacional de Salud Mental (INSM) [Honorio Delgado-Hideyo Noguchi National Institute of Mental Health]. This original research was approved by the INSM's Ethics Committee and the present research by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia [Cayetano Heredia Peruvian University].

DataThe information was collected in 24 public health facilities in the city of Lima and Callao, dependent on the Ministry of Health of Peru. These included eight general hospitals with a large movement of patients, and their corresponding primary health centres, two for each hospital. The sample of the original study conducted between July and November 2015, was 10,885 adults aged 18 years or older. The subjects were selected from among the people waiting to be seen in different specialties. For the present study, only those patients with a diagnosis of type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus and whose information was complete were considered.

MeasurementsThe presence was determined of a current depressive episode (in the last two weeks), an episode in the last 12 months, or at some point in life. For this, the module that evaluates the depressive episode according to the ICD-10 of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Spanish version ICD-1010) was used, modified to obtain the annual and lifetime frequency, and linguistically adapted in previous studies conducted by the INSM. The psychometric analysis of depressive symptoms reached a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.665.11

Quality of life was measured using the Mezzich Quality of Life Index (Spanish version).12 This consists of 10 items that include physical well-being, psychological or emotional well-being, self-care and independent functioning, occupational functioning, interpersonal functioning, social-emotional support, community and service support, personal fulfilment, spiritual satisfaction, and overall quality of life. Each item is rated by the subject on an ordinal scale of 1–10 points. This instrument was linguistically adapted and validated for the Peruvian population, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.867.13

The diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was obtained from the daily statistical report of care provided by the treating physician, regardless of whether it was type 1 or type 2. The covariates include age group in years (18−30, 30−45, 45−60 and over 60), gender, level of education (primary, secondary, non-university higher, university) and marital status (single, married, cohabiting, and grouping together those who were separated, divorced or widowed).

Statistical analysisThe database was analysed with the statistical software Stata 14 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). A significance level of 0.05 was considered in all the statistical tests. An exploratory analysis was made of the variables that could be associated with depression. For this, a chi square test was performed first and only those variables with a p value <0.05 (gender, age, educational level and marital status) were included in the logistic regression models.

The quality of life analysis was carried out in each of the 10 areas in the Mezzich quality of life index and for this the T test was used. The results are shown as mean and standard deviation. To obtain the minimum clinically important difference (MCID), the mean standard deviation value of the quality of life variable was determined,14,15 which was equivalent to 0.74. Then it was determined if the difference between patients with DM and depression and those with DM but without depression in each area of the quality of life is greater than 0.74. In the areas where this occurred, an MCID was established.

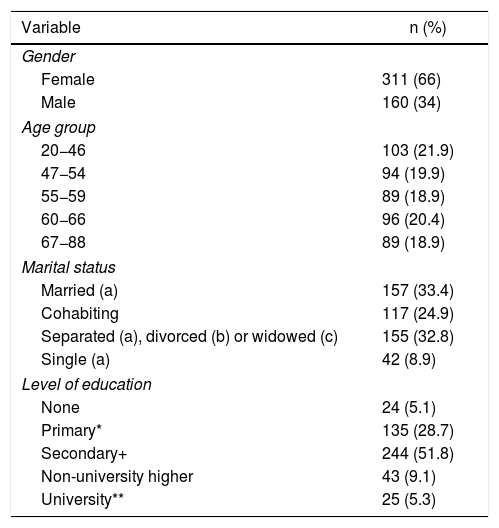

ResultsOf 471 patients with diabetes mellitus registered in the database, 468 were included for the study. The average age of these patients was 55 + 12.2 years. The rate of current depression was 5.9%, the annual 8.6% and the lifetime 31.8%. Most of the participants were female and were married or cohabiting. As regards their educational level, the majority had reached at least the secondary level (Table 1).

Characteristics of the population.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 311 (66) |

| Male | 160 (34) |

| Age group | |

| 20−46 | 103 (21.9) |

| 47−54 | 94 (19.9) |

| 55−59 | 89 (18.9) |

| 60−66 | 96 (20.4) |

| 67−88 | 89 (18.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Married (a) | 157 (33.4) |

| Cohabiting | 117 (24.9) |

| Separated (a), divorced (b) or widowed (c) | 155 (32.8) |

| Single (a) | 42 (8.9) |

| Level of education | |

| None | 24 (5.1) |

| Primary* | 135 (28.7) |

| Secondary+ | 244 (51.8) |

| Non-university higher | 43 (9.1) |

| University** | 25 (5.3) |

*Includes pre-primary education.

+Includes baccalaureate (A-level equivalent).

** Includes postgraduate.

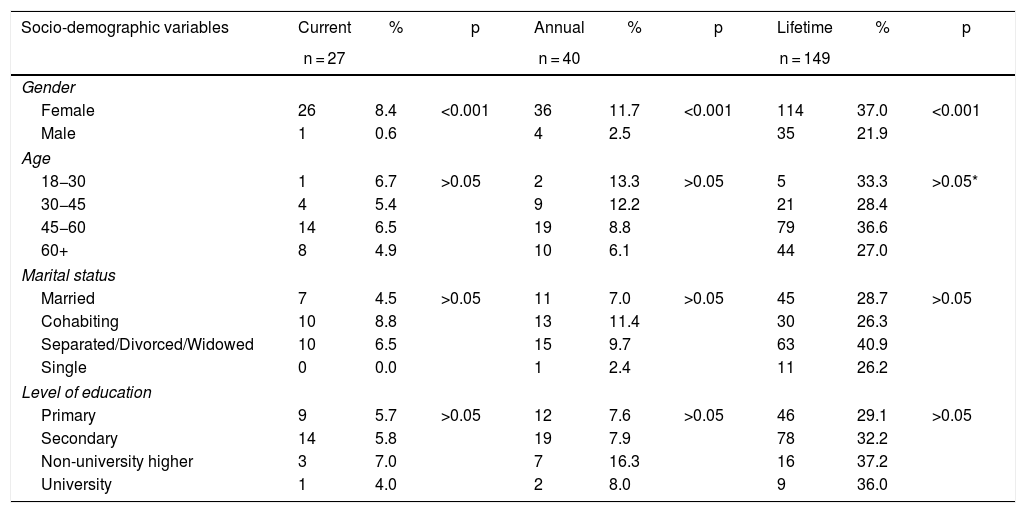

Table 2 shows that women had a higher rate of depression, whether it was current, in last 12 months, or at some point in their life (8.44%, 11.69% and 37.01% respectively, p < 0.0001). With regard to age, there were no differences in depression between groups in the current, annual and lifetime categories, except for the higher rate of depression in adults aged 45−60 years (36.57%) compared to adults older than 60 years (26.99%). In the case of marital status, it was found that cohabiting diabetics had a higher frequency of depression than those who were single (8.77% vs 0%, p < 0.05). In addition, in the lifetime rate, married people presented less depression than those who were separated, widowed or divorced (28.66% vs 40.91%, p < 0.05). By educational level, no differences were found for current, annual or lifetime depression.

Sociodemographic variables of diabetic patients with depressive episode who were treated at public health centres in Metropolitan Lima.

| Socio-demographic variables | Current | % | p | Annual | % | p | Lifetime | % | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 27 | n = 40 | n = 149 | |||||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 26 | 8.4 | <0.001 | 36 | 11.7 | <0.001 | 114 | 37.0 | <0.001 |

| Male | 1 | 0.6 | 4 | 2.5 | 35 | 21.9 | |||

| Age | |||||||||

| 18−30 | 1 | 6.7 | >0.05 | 2 | 13.3 | >0.05 | 5 | 33.3 | >0.05* |

| 30−45 | 4 | 5.4 | 9 | 12.2 | 21 | 28.4 | |||

| 45−60 | 14 | 6.5 | 19 | 8.8 | 79 | 36.6 | |||

| 60+ | 8 | 4.9 | 10 | 6.1 | 44 | 27.0 | |||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married | 7 | 4.5 | >0.05 | 11 | 7.0 | >0.05 | 45 | 28.7 | >0.05 |

| Cohabiting | 10 | 8.8 | 13 | 11.4 | 30 | 26.3 | |||

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 10 | 6.5 | 15 | 9.7 | 63 | 40.9 | |||

| Single | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.4 | 11 | 26.2 | |||

| Level of education | |||||||||

| Primary | 9 | 5.7 | >0.05 | 12 | 7.6 | >0.05 | 46 | 29.1 | >0.05 |

| Secondary | 14 | 5.8 | 19 | 7.9 | 78 | 32.2 | |||

| Non-university higher | 3 | 7.0 | 7 | 16.3 | 16 | 37.2 | |||

| University | 1 | 4.0 | 2 | 8.0 | 9 | 36.0 | |||

NS: Not significant (p > 0.05, unless otherwise indicated).

Regarding lifetime frequency, it was found that patients between 45 and 60 years of age had more severe depression than those 60 and older (p < 0.05) + . In current frequency, those cohabiting presented a higher percentage of depression than single people (p < 0.05)°. In lifetime frequency, married people had a lower percentage of depression than those separated/divorced/widowed (p < 0.05).

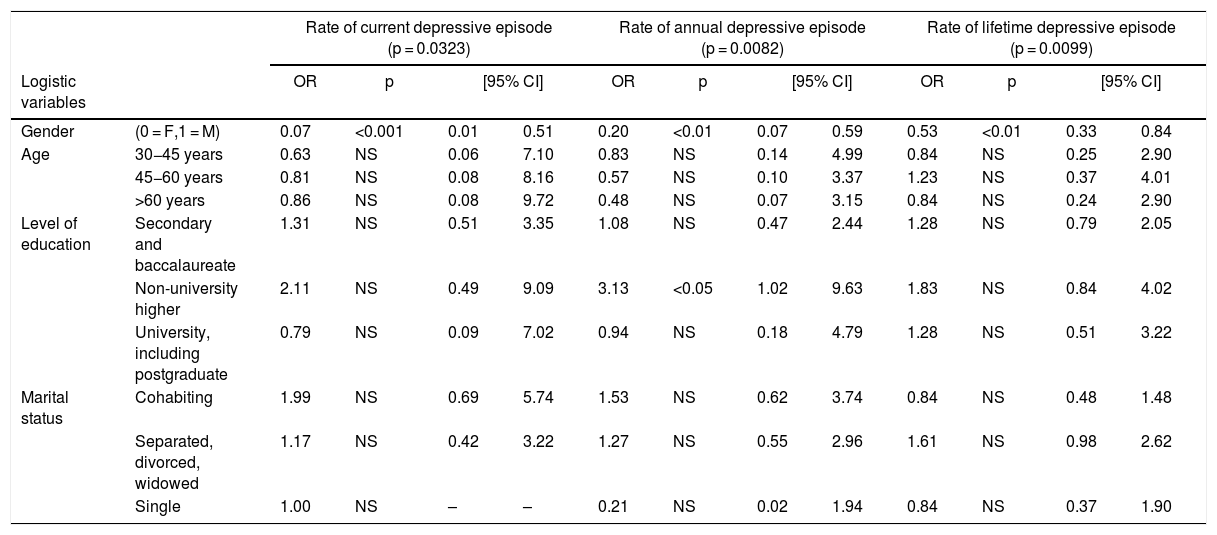

The logistic regression showed that gender was the only factor associated with depression, in the current, annual and lifetime frequencies. Moreover, the annual frequency of a depressive episode was associated with having a non-university higher education level (Table 3).

Logistic regression: Shows the significance of the selected variables versus the final status of the depressive patient by categories.

| Rate of current depressive episode (p = 0.0323) | Rate of annual depressive episode (p = 0.0082) | Rate of lifetime depressive episode (p = 0.0099) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic variables | OR | p | [95% CI] | OR | p | [95% CI] | OR | p | [95% CI] | ||||

| Gender | (0 = F,1 = M) | 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.51 | 0.20 | <0.01 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 0.53 | <0.01 | 0.33 | 0.84 |

| Age | 30−45 years | 0.63 | NS | 0.06 | 7.10 | 0.83 | NS | 0.14 | 4.99 | 0.84 | NS | 0.25 | 2.90 |

| 45−60 years | 0.81 | NS | 0.08 | 8.16 | 0.57 | NS | 0.10 | 3.37 | 1.23 | NS | 0.37 | 4.01 | |

| >60 years | 0.86 | NS | 0.08 | 9.72 | 0.48 | NS | 0.07 | 3.15 | 0.84 | NS | 0.24 | 2.90 | |

| Level of education | Secondary and baccalaureate | 1.31 | NS | 0.51 | 3.35 | 1.08 | NS | 0.47 | 2.44 | 1.28 | NS | 0.79 | 2.05 |

| Non-university higher | 2.11 | NS | 0.49 | 9.09 | 3.13 | <0.05 | 1.02 | 9.63 | 1.83 | NS | 0.84 | 4.02 | |

| University, including postgraduate | 0.79 | NS | 0.09 | 7.02 | 0.94 | NS | 0.18 | 4.79 | 1.28 | NS | 0.51 | 3.22 | |

| Marital status | Cohabiting | 1.99 | NS | 0.69 | 5.74 | 1.53 | NS | 0.62 | 3.74 | 0.84 | NS | 0.48 | 1.48 |

| Separated, divorced, widowed | 1.17 | NS | 0.42 | 3.22 | 1.27 | NS | 0.55 | 2.96 | 1.61 | NS | 0.98 | 2.62 | |

| Single | 1.00 | NS | – | – | 0.21 | NS | 0.02 | 1.94 | 0.84 | NS | 0.37 | 1.90 | |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; NS = p >0.05.

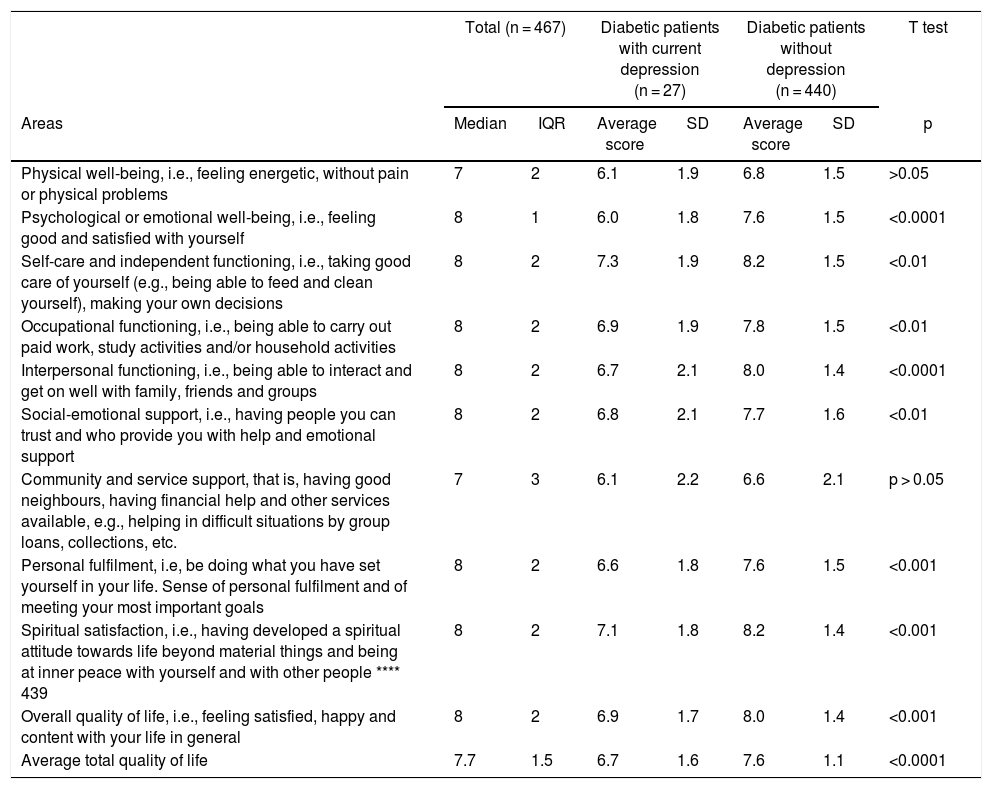

The quality of life in diabetic patients was lower when they had current depression (6.7 vs. 7.6 p < 0.0001) (Table 4). When the differences in each of the parameters that make up this Mezzich scale were analysed, the same difference was observed with the exception of the areas of psychological or emotional well-being and in the area of community and service support (p > 0.05). Comparing the same, but using the minimum clinically important difference (MCID), it was found that both physical well-being and community and service support did not have a clinically important difference.

Quality of life in diabetic patients with and without depression.

| Total (n = 467) | Diabetic patients with current depression (n = 27) | Diabetic patients without depression (n = 440) | T test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Areas | Median | IQR | Average score | SD | Average score | SD | p |

| Physical well-being, i.e., feeling energetic, without pain or physical problems | 7 | 2 | 6.1 | 1.9 | 6.8 | 1.5 | >0.05 |

| Psychological or emotional well-being, i.e., feeling good and satisfied with yourself | 8 | 1 | 6.0 | 1.8 | 7.6 | 1.5 | <0.0001 |

| Self-care and independent functioning, i.e., taking good care of yourself (e.g., being able to feed and clean yourself), making your own decisions | 8 | 2 | 7.3 | 1.9 | 8.2 | 1.5 | <0.01 |

| Occupational functioning, i.e., being able to carry out paid work, study activities and/or household activities | 8 | 2 | 6.9 | 1.9 | 7.8 | 1.5 | <0.01 |

| Interpersonal functioning, i.e., being able to interact and get on well with family, friends and groups | 8 | 2 | 6.7 | 2.1 | 8.0 | 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| Social-emotional support, i.e., having people you can trust and who provide you with help and emotional support | 8 | 2 | 6.8 | 2.1 | 7.7 | 1.6 | <0.01 |

| Community and service support, that is, having good neighbours, having financial help and other services available, e.g., helping in difficult situations by group loans, collections, etc. | 7 | 3 | 6.1 | 2.2 | 6.6 | 2.1 | p > 0.05 |

| Personal fulfilment, i.e, be doing what you have set yourself in your life. Sense of personal fulfilment and of meeting your most important goals | 8 | 2 | 6.6 | 1.8 | 7.6 | 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Spiritual satisfaction, i.e., having developed a spiritual attitude towards life beyond material things and being at inner peace with yourself and with other people **** 439 | 8 | 2 | 7.1 | 1.8 | 8.2 | 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Overall quality of life, i.e., feeling satisfied, happy and content with your life in general | 8 | 2 | 6.9 | 1.7 | 8.0 | 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Average total quality of life | 7.7 | 1.5 | 6.7 | 1.6 | 7.6 | 1.1 | <0.0001 |

IQR: interquartile range.

SD: standard deviation.

Our results indicate that DM patients from Metropolitan Lima attending public health centres present more depression than the general population. In the present study, the current rate of depression in diabetic patients was 5.77%, the annual rate was 8.55% and the lifetime was 31.84%, while in the general population of Metropolitan Lima the prevalence of current depression was found to be 2.8%, the annual, 6.2% and lifetime, 17.2%.16 In 1993, it was found that people with DM had a prevalence of depression three times higher than the general population.17 In another meta-analysis of 42 studies that included 20,218 patients with DM, it was found that depression is twice as common in people with DM compared to the general population.18 In a meta-analysis of 10 controlled studies, Ali et al. obtained a rate of depression among those with type 2 DM that was almost twice as high.19 We believe that it is important to examine the course of depression in patients with a long-standing diagnosis of diabetes.

It has been suggested that depressive symptoms could be a consequence of the burden of DM. The number of chronic diseases seems to explain part of the association between DM and depressive symptoms.20 Depression in DM would thus be a multi-determined phenomenon resulting from the interaction between biological and psychosocial factors.21 But the higher incidence of depression in patients with diabetes may be a consequence of central insulin resistance. Insulin resistance in the brain can cause alterations in mitochondrial function, increased levels of monoamine oxidases, and increased clearance of dopamine.22 It has been suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction may contribute to depression.23 Insulin resistance is directly related to the severity of depression symptoms in individuals without DM.24 But it is one of several mechanisms associated with depression, such as decreased dopamine neurotransmission.25 These alterations can also interact with other factors that may contribute to depression and anxiety, including genetic susceptibility, alterations in circadian rhythms, or changes in the content of monoamines such as serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine.26 People newly diagnosed with DM have fewer symptoms of depression than those already diagnosed.27 With ageing, brain-specific insulin receptor knockout mice show signs equivalent to depression.24

These biochemical variations would explain the abnormal brain imaging findings in people with DM, which include altered brain activity and connectivity by functional magnetic resonance imaging,28 altered microstructure by diffusion tensor imaging29 and altered neuronal circuits in the corpus striatum.30

In other studies carried out in Peru in patients with DM, high prevalences of depression have been found. In Metropolitan Lima, the current prevalence of depression was 73.3%31, in Chiclayo it was 57.78%32, and in Trujillo it was 38.21%33. This dissimilarity in the results can be attributed to methodological differences. In the case of our study, a categorical diagnostic instrument was used, based on the presence or absence of a depressive episode according to the operational criteria of the ICD-10, while in the other studies, dimensional instruments such as the Beck Depression Inventory were used. It is also possible that ethnocultural factors could have caused measurement biases,34 or because the study was conducted among hospitalised or more seriously ill patients, who will have higher percentages of depression.

Women had a higher frequency of depression, which is what was found in similar studies.11,35 In the general population, being a woman is associated with higher rates of depression.36 One reason to explain this higher frequency in the female gender could be that women perform less physical activity (which is a protective factor of depression) than men, which would predispose them to have depression.37. In their study, Khuwaja et al. reported that the social role that women have (passivity, dependence, emotional expression) allows them to better express their emotions and thus identify when they feel depressed.34 But we consider that the main reason is that women have greater insulin resistance than men,38 which would explain why they have a higher percentage of depression.30

Meanwhile, we did not find that age, marital status or educational level were related to depression. But, in the analysis, we found that those cohabiting presented a higher percentage of depression than single people, and that, in those who were married, the percentage of depression was lower than in those separated/divorced/widowed. Chew also found a higher percentage of depression among separated/divorced.39

Our diabetics with depression had a lower quality of life. In patients with diabetes, depression seems to be a determining factor of a poor quality of life.40 High levels of depression have been reported to have a negative impact on quality of life. Eren et al. classify depression as a pervasive condition and assert that its impact on the quality of life of diabetics is directly proportional to the severity of the depression.41 The simultaneous presence of DM and depression causes poorer self-care42 than when each disease presents separately, and also decreases adherence to treatment and the quality of life, and increases complications43 and mortality44, all of which translates into an increase in health costs.45

When we separately analysed the ten areas that make up the quality of life questionnaire that we used, we found that the scores were lower in DM patients with depression in all areas except in psychological and emotional well-being, and in community and service support. The physical, social and emotional condition of diabetic patients is diminished.46 In DM, there is a loss of muscle mass and polyneuropathy, which causes a reduction in muscle strength, leading to a decrease in physical well-being that is greater when the person is in a depressed state.47 The self-care of most people with DM is not so good. This is because at diagnosis DM patients are adults, and thus teaching control measures is a challenge. This learning process is hampered even more if they have depression, since depression intervenes negatively in the cognitive processes of learning.48

As this is a cross-sectional study, the first limitation is that we were only able to observe one moment in the life of DM patients treated at health facilities in Lima. Being a survey-only study, we do not know the true level of their DM or if its treatment was carried out adequately or not. Another limitation is the selection bias of the participants, since only those attending public sector hospitals were selected. However, this was taken into account when making the conclusions.

ConclusionThe rate of depression in patients with diabetes who are treated on an outpatient basis at public health centres is higher than in the general population and their quality of life is significantly reduced, which raises the need to consider depression as an additive factor to the burden of morbidity of this condition.

Funding sourceNone.

Academic thesis for the qualification of PhysicianPrevalence of depression and its associated factors in patients with diabetes mellitus attending the outpatient clinic of general hospitals and health centres in Metropolitan Lima and Callao –2015, 2018, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Accinelli RA, Arias KB, Leon-Abarca JA, López LM, Saavedra JE. Frecuencia de depresión y calidad de vida en pacientes con diabetes mellitus en establecimientos de salud pública de Lima Metropolitana. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:243–251.