To evaluate the influence of the factors associated with overall functioning in patients with schizophrenia who attended the outpatient clinic of the Hospital Nacional de la Policía [National Police Hospital] “Luis Nicasio Saenz” in 2018–2019.

MethodologyNon-experimental quantitative study of a descriptive cross-sectional correlational type. Convenience sampling was carried out, and consisted of 53 patients with schizophrenia. Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) was used to assess overall functioning, the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP) for cognitive functioning, and a data collection sheet with sociodemographic data and a history of the disease.

ResultsIt was found that 34 (62.2%) patients were male; 52 (98.1%), single; 39, (73.6%) without a current job. We found worse overall functioning in patients with a lower educational level (P = .005) and without a current job (P = .004). The total FAST was correlated with the time of the disease (ρ = 0.334, P < .05), the number of previous psychotic episodes (ρ = 0.354, P < .01), the total SCIP score (ρ = 0.542, P < .01) and their working memory dimension (VMT) (ρ = −0.523, P < .05). In the multiple linear regression model, it was found that the variables that most influenced the FAST were the total SCIP score (Beta = −0.528) and the number of previous psychotic episodes (Beta = 0.278).

ConclusionThe associated factors that most influence overall functioning in this sample of Peruvian patients with schizophrenia are cognitive functioning and the number of previous psychotic episodes.

Evaluar la influencia de los factores asociados al funcionamiento global en pacientes con esquizofrenia que acuden a la consulta externa del Hospital Nacional de la Policía “Luis Nicasio Saenz” durante los años 2018–2019.

MetodologíaEstudio cuantitativo observacional de tipo descriptivo transversal correlacional. La muestra fue por conveniencia y estuvo constituida por 53 pacientes con esquizofrenia. Se utilizó el Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) para valorar el funcionamiento global, el Screen for Cognitive Impairment (SCIP) para el funcionamiento cognitivo y una ficha de recolección de datos sociodemográficos y de historia de la enfermedad.

ResultadosSe encontró que 34 (62.2%) pacientes fueron varones; 52 (98.1%), solteros; 39 (73.6%), sin un trabajo actual. Se halló un peor funcionamiento global en los pacientes con menor nivel educativo (P = .005) y sin un trabajo actual (P = .004). El total del FAST se correlacionó con el tiempo de la enfermedad (ρ = 0.334, P < .05), el número de episodios psicóticos previos (ρ = 0.354, P < .01), el puntaje total del SCIP (ρ = 0.542, P < .01) y su dimensión memoria de trabajo (VMT) (ρ = −0.523, P < .05). En el modelo de regresión lineal múltiple se encontró que las variables que más influyeron en el FAST fueron el puntaje total del SCIP (Beta = −0.528) y el número de episodios psicóticos previos (Beta = 0.278).

ConclusiónLos factores asociados que más influyen en el funcionamiento global en esta muestra de pacientes con esquizofrenia peruanos son el funcionamiento cognitivo y el número de episodios psicóticos previos.

Schizophrenia is a chronic mental disorder that produces high costs, has a substantial impact on healthcare budgets globally, and accounts for 1.5%–3% of total national healthcare expenditures.1 Despite its low lifetime prevalence (4 per 1000 people), the health, social and economic burden related to schizophrenia is very significant, not only for patients, but also for families, caregivers and society in general.2 The study “Carga de enfermedad en el Perú: estimación de los años de vida saludables perdidos 2012” [Burden of disease in Peru: estimate of healthy years of life lost 2012] revealed that neuropsychiatric diseases ranked first in healthy years of life lost (HeaLY) in the Peruvian population aged 15–44 years. Schizophrenia has a prominent position in this category, occupying the fourth place in HeaLY.3

This illness, usually considered the most devastating mental disorder, notably affects the global functioning of patients (at the level of autonomy, work, cognitive function, finances, interpersonal relationships and leisure, among others). The high costs of the illness and the HeaLY already described are mainly due to poor global functioning, which indicates the importance of its evaluation. The concept of functioning is complex, and is broken down into different dimensions according to the capabilities of the patient to: study, maintain friendships, enjoy life, live independently, and work. Poor global functioning has been related to several variables, such as poor cognitive function.4–6 In a meta-analysis, neurocognition and social cognition were found to be associated with functionality in patients with schizophrenia with small to medium effect size.4 The strongest associations were between verbal fluency and functioning, and between verbal memory and social functioning. Functioning has also been related to clinical and disease history variables such as negative, extrapyramidal, and depressive symptoms, greater number of psychotic episodes, etc.6

However, despite the importance of global functioning, it does not tend to be evaluated in psychiatric outpatient consultations for various reasons (large number of patients, more attention is paid to positive psychotic symptoms, etc.), a situation that occurs worldwide and also in Peru. At the Hospital Nacional “Luis Nicasio Saenz” de la Policía Nacional del Perú (HN-LNS-PNP) [Luis Nicasio Saenz National Hospital of the National Police of Peru], there are no protocols for global functioning assessment in patients with schizophrenia attending the outpatient clinic. Therefore, neither its status nor its associated factors are known. This situation is worrying, since if we do not assess global functioning, we will not be able to carry out suitable specific rehabilitation programmes. Furthermore, we must consider that the different factors associated with functioning in patients with schizophrenia reported in other studies could vary due to the Peruvian cultural characteristics and its health system.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the influence of sociodemographic factors, disease history and dimensions of cognitive performance on global functioning in a sample of patients with schizophrenia who attended the HN-LNS-PNP outpatient clinic in 2018 and 2019.

Material and methodsThe study was a quantitative, non-experimental, descriptive, cross-sectional, correlational study. The study population was patients diagnosed with schizophrenia at the HN-LNS-PNP who met the following selection criteria:

Inclusion criteria:

- •

Aged 18−59 years.

- •

Having a diagnosis of a schizophrenic spectrum disorder.

- •

Stable phase of the disorder, defined as not having been hospitalised in the last three months and without changes in psychopharmacological treatment during the last month.

- •

Information from the interview corroborated by a family member or another person.

Exclusion criteria:

- •

Presence of a neurological disease that produces impaired cognitive function.

- •

Presence of consumption of toxic substances.

- •

Presence of major affective disorders.

- •

Difficulties in reading and writing.

The type of sampling was non-probabilistic for convenience. Interviews with patients were conducted from June 2018 to May 2019 in the outpatient clinic of the HN-LNS-PNP Department of Psychiatry. After checking if patients met the selection criteria, they were invited to participate in the study and its purpose was explained to them in a clear, simple and comprehensive way. The research protocol was applied, which consisted of a data collection sheet for sociodemographic data and disease history prepared ad hoc, and scales to assess global and cognitive functioning.

Assessment of global functioningThe Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) was applied, which is a scale initially developed to be able to carry out an assessment of global functioning and its impairment in patients with bipolar affective disorder. However, it has also been shown to have suitable psychometric properties in terms of validity and reliability in patients with schizophrenia, with high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha of 0.89).7 It is easy to apply and takes approximately 3−6 min. It assesses the primary difficulties in psychosocial functioning that present. It has a total of 24 items, each of which has operational scoring criteria that range from 0 to 3. The higher the score, the greater the difficulty, as stated in the application manual.8 The 24 items are grouped into six specific dimensions of functioning: autonomy, occupational functioning, cognitive functioning, financial issues, interpersonal relationships and leisure time.

Assessment of cognitive functioningThe cognitive assessment was carried out with the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP). This instrument was designed to assess the cognitive functioning of psychiatric patients in daily clinical practice. It has the advantage, compared to other types of cognitive evaluations, of being able to be applied in a short period of time (±15−20 min), in addition to not having additional costs, since it does not require a test kit.9,10 This scale was translated from English to Spanish, with a factorial structure and similar intraclass correlation coefficients found in both versions.11 It assesses five cognitive dimensions through five subtests:

- 1)

Immediate verbal learning test (VLT-I): derived from the Rey Audio Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT). The patient is given a series of 30 stimulus words assigned in groups of 10. The examinee has to listen to these 10 words that are read by the examiner with an interval of 3 seconds between them. At the end, the patient is asked to recall the words, in the order they prefer. This process is repeated three times. The primary score of the VLT-I is the total number of words that the patient remembers, and can be evaluated as: low (0–15), moderate (16–19), high (20–23) and very high (24–30).11,12

- 2)

Working memory test (VMT): derived from the Brown-Peterson Consonant Trigram Test (CTT). To administer the SCIP, eight consonant trigrams are selected, then each set of three letters is read to the patient. The first two trigrams have no delay, the next two trigrams have a delay of three seconds, the next two have a nine second delay and the last two have a delay of 18 s, with the task of counting backwards and then the patient must remember the letters of the trigram in any order.11 The main measure to assess is the number of individual letters remembered in the eight trigrams (total of 24). It can also be evaluated as: very low (0–11), low (12–16), moderate (17–20) and high (21–24).12

- 3)

Verbal fluency test (VFT): derived from the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT). The patient is given a letter (C), and is asked to generate as many words as possible from the letter in 30 s. It is also explained that they should not say numbers, proper names or derived words. The procedure is repeated with the next letter (L). The main measure that is recorded is the total number of words generated with these conditions. It can also be assessed as: very low (0–7), low (8–13), moderate (14–18) and high (≥19).12

- 4)

Delayed verbal learning test (VLT-D): the patient is asked for the words they remember from the VLT-I. It can be evaluated as: very low (0–2), low (3–4), moderate (5–6), high (7–8) and very high (9–10).12

- 5)

Processing speed test (PST): developed from Morse Code. The patient has six letters of the alphabet with their respective Morse code symbols. A random distribution of these six letters is made in four rows of nine boxes, with a white space under each letter. It is explained to the patient that they must fill in the blank space of each letter with its corresponding Morse code symbol. The first six boxes are for practice, after which the patient has 30 s to fill in the remaining boxes. The main score recorded is the total number of boxes that are completed correctly during the 30 s.11 It can also be assessed as: low (0–6), moderate (7–10), high (11–15) and very high (16–30).12

The sociodemographic data of each patient were also obtained: age, gender, marital status, level of education, occupation before becoming ill, and current job. The patient was also asked about the history of their illness: age at first nonspecific symptom, age at first psychotic symptom, age at first treatment, duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), duration of untreated illness (DUI), total duration of illness and number of previous psychotic episodes.

Data processing and analysisDescriptive statistics techniques were performed for all variables. The mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum for numerical variables, and frequency analysis for categorical variables were reported.

The relationship between the FAST and the qualitative variables was evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test or Student's t-test depending on whether they met the normality assumptions. The linear correlation between the FAST, the SCIP and the other quantitative variables was evaluated using Spearman's rho.

A multiple linear regression model was constructed in which all the variables other than the total FAST result were considered using the forward method. The variables that were significant were selected and the assumptions of the linear regression were verified by evaluating the residuals.

Ethical aspectsEach participant, or their responsible family member, was asked to sign an informed consent form, which provided a basic outline of the research, and of the rights of the participants (anonymity and refraining from participating if deemed appropriate). The research was carried out with the authorisation of the Oficina de Capacitación y Docencia [Office of Training and Teaching] of the HN-LNS-PNP and the Faculty of Human Medicine of the University of San Martín de Porres.

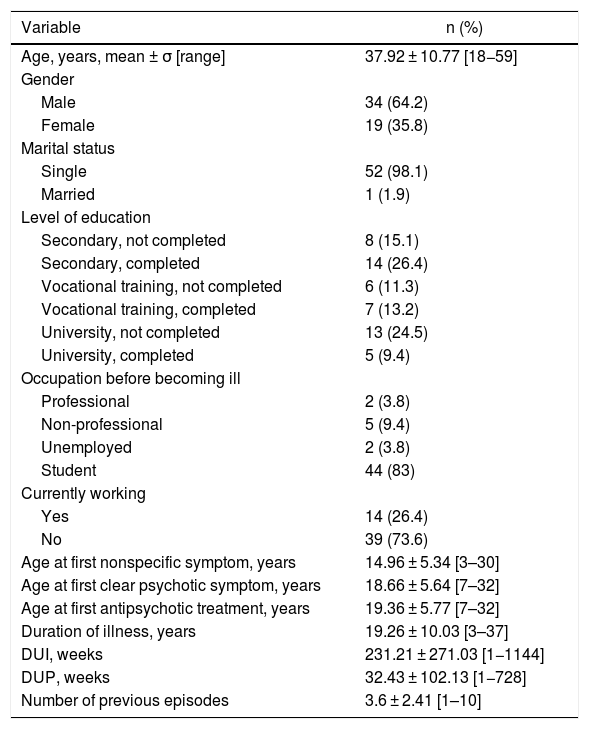

ResultsA total of 53 patients with schizophrenia who attended the outpatient clinic of the HN-LNS-PNP Department of Psychiatry during the study period were evaluated. The mean age was 37.92 (±10.77) years. The other sociodemographic characteristics and the history of illness are shown in Table 1. The mean FAST score was 36.83 (± 16.44) points. With a minimum value of 1 and a maximum of 72. The mean score of the total SCIP was 51.89 ± 16.66 [25–86], and that of the SCIP subtests: VLI-I: 14.64 ± 4.26 [5–23], VMT: 13.77 ± 4.51 [6–24], VFT: 13.85 ± 6.04 [4–29], VLT-D: 3.28 ± 2.62 [0–8]; y PST: 6.34 ± 3.66 [0–16].

Sociodemographic characteristics and those of history of illness of 53 schizophrenia patients of the HN-LNS-PNP.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± σ [range] | 37.92 ± 10.77 [18−59] |

| Gender | |

| Male | 34 (64.2) |

| Female | 19 (35.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 52 (98.1) |

| Married | 1 (1.9) |

| Level of education | |

| Secondary, not completed | 8 (15.1) |

| Secondary, completed | 14 (26.4) |

| Vocational training, not completed | 6 (11.3) |

| Vocational training, completed | 7 (13.2) |

| University, not completed | 13 (24.5) |

| University, completed | 5 (9.4) |

| Occupation before becoming ill | |

| Professional | 2 (3.8) |

| Non-professional | 5 (9.4) |

| Unemployed | 2 (3.8) |

| Student | 44 (83) |

| Currently working | |

| Yes | 14 (26.4) |

| No | 39 (73.6) |

| Age at first nonspecific symptom, years | 14.96 ± 5.34 [3–30] |

| Age at first clear psychotic symptom, years | 18.66 ± 5.64 [7–32] |

| Age at first antipsychotic treatment, years | 19.36 ± 5.77 [7–32] |

| Duration of illness, years | 19.26 ± 10.03 [3–37] |

| DUI, weeks | 231.21 ± 271.03 [1−1144] |

| DUP, weeks | 32.43 ± 102.13 [1−728] |

| Number of previous episodes | 3.6 ± 2.41 [1–10] |

DUI: duration of untreated illness.

DUP: duration of untreated psychosis.

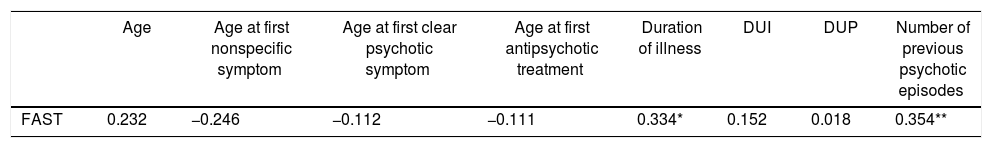

The bivariate analyses of the total FAST score with the sociodemographic variables can be found in Table 2. The correlation coefficients between the FAST with age and the variables of the history of illness are shown in Table 3. The coefficients of the correlation between the FAST and the SCIP subtests are shown in Table 4. The most powerful and significant correlations were between the FAST and the total SCIP (ρ = −0.542, P < .05) and with the VMT (ρ = −0.523, P < .05).

Comparative analysis according to the sociodemographic variables for the mean FAST scores.

| Variable | n (%) | FAST | |

|---|---|---|---|

| X ± σ [95% CI: lower limit–upper limit] | P | ||

| Gender | .568 | ||

| Male | 34 (64.2) | 35.85 ± 17.71 [29.67–42.03] | |

| Female | 19 (35.8) | 38.58 ± 14.17 [31.75–45.41] | |

| Level of education | .005 | ||

| Secondary, not completed | 8 (15.1) | 51.88 ± 11.28 [42.44–61.31] | |

| Secondary, completed | 14 (26.4) | 38.86 ± 12.60 [31.58–46.14] | |

| Vocational training, not completed | 6 (11.3) | 45.17 ± 13.25 [31.25–59.08] | |

| Vocational training, completed | 7 (13.2) | 26.57 ± 14.51 [13.15–39.99] | |

| University, not completed | 13 (24.5) | 31.77 ± 16.39 [21.86–41.67] | |

| University, completed | 5 (9.4) | 24.60 ± 20.23 [−0.52 to 49.72] | |

| Currently working | .004 | ||

| Yes | 14 (26.4) | 23.57 ± 18.56 [12.85–34.29] | |

| No | 39 (73.6) | 41.59 ± 12.81 [37.44–45.74] |

CI: confidence interval; FAST: Functioning Assessment Short Test.

P values obtained through Student's t-test for gender and currently working, and ANOVA for educational level.

Correlation coefficients of the total FAST score with age and the history of illness variables.

| Age | Age at first nonspecific symptom | Age at first clear psychotic symptom | Age at first antipsychotic treatment | Duration of illness | DUI | DUP | Number of previous psychotic episodes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAST | 0.232 | −0.246 | −0.112 | −0.111 | 0.334* | 0.152 | 0.018 | 0.354** |

FAST: Functioning Assessment Short Test; DUI: duration of untreated illness; DUP: duration of untreated psychosis.

Correlation coefficients of the total FAST scores with the total SCIP scores and its subtests.

VLT-I: Verbal Learning Test-Immediate recall; VMT: Working Memory Test; VFT: Verbal Fluency Test; VLT-D: Verbal Learning Test-Delayed recall; PST: Processing Speed Test; SCIP: Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry; FAST: Functioning Assessment Short Test.

*P < .05.

The multiple linear regression analysis with the total FAST score as the explained variable showed that there was a relationship between variables that is explained by the equation:

where Y is the total FAST score, X1 the total SCIP and X2 the number of previous psychotic episodes. The coefficient of determination was 0.392 and the mean square error 161.46. The Durbin-Watson statistic was 1.529. Table 5 shows the standardised coefficients and their probability values. The assumptions of homoscedasticity and normality in the linear regression of the standardised residuals were verified, and were met.Multiple linear regression models.

| Model | [0.3−4]Non-standardised coefficients | Standardised coefficients | t | Sig. | 95% CI for B (lower limit–upper limit) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard error | Beta | |||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 65.586 | 6.227 | 10.532 | 0.000 | (53.084–78.087) | |

| Total SCIP | −0.554 | 0.114 | −0.561 | −4.846 | 0.000 | (−0.784 to −0.325) | |

| 2 | (Constant) | 57.032 | 6.843 | 8.334 | 0.000 | (43.288–70.777) | |

| Total SCIP | −0.521 | 0.110 | −0.528 | −4.750 | 0.000 | (−0.741 to −0.301) | |

| Number of previous psychotic episodes | 1.896 | 0.758 | 0.278 | 2.503 | 0.016 | (0.375–3.418) | |

CI: Confidence interval; SCIP: Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry.

Dependent variable: total FAST.

This is the first exploratory pilot analysis of the factors associated with global functioning, with special emphasis on cognitive functioning and the history of illness, in Peruvian patients with schizophrenia. Regarding the general characteristics of the study sample, the mean age was 37.92 (±10.77) years, which is similar to that reported in other studies.7,12,13 This age corresponds to the economically active population. It is also represented mostly by unemployed single men. These sociodemographic characteristics are similar to those reported in other samples of patients with schizophrenia.11,12,14,15 Various studies have shown that the percentage of patients with schizophrenia who marry is much lower than in normal individuals or those with other psychiatric disorders. This is due to a poor premorbid adjustment, social and work disability, an early onset of the condition, clinical symptoms and problems in satisfying sexuality and the need for intimacy.16–18 Being unemployed is a characteristic of patients with schizophrenia. A recent study found that employment rates in this population were 10.24%–10.5% for men and 9.8% for women.19 These low employment rates have important implications for the effect of the disorder on the individual, the family (dependency) and society (loss of productivity and the need for an additional source of income, social stigma).20 For some researchers, low employment rates are not intrinsic to schizophrenia, but rather a reflection of the interaction between the social and economic pressures that patients face, the labour market, and the psychological and social barriers to employment.21

Regarding the characteristics of the history of illness, it was found that the mean age when the first clear psychotic symptom occurred was 18.66 (±5.34) years. This age corresponds to that reported in the literature, in which it is mentioned that schizophrenia generally begins in young adults between 15 and 35 years old.22 However, it is lower than that reported in a meta-analysis, in which it was found that schizophrenia appeared at 24.4 years.23 A DUI of 231.21 (±271.03) weeks was found and a DUP of 32.43 (±102.13) weeks. DUI is defined as the time from the appearance of the first nonspecific symptom to the start of adequate psychopharmacological treatment, while DUP has the same endpoint, but begins with the manifestation of the first clear psychotic symptom.24 Various studies have shown that the mean value of DUP is within the range of 8–48 weeks,24 which is similar to that reported in this study.

A mean FAST score of 36.83 (±16.44) points was found, which has significant differences when grouped according to educational level and whether currently working. These findings are partially similar to those reported by Osorio-Martínez,15 who found, in a sample of Peruvian schizophrenia patients from the Hermilio Valdizán Hospital, that those who had completed only primary school showed higher FAST scores than those who had completed secondary school and higher education.15 That study found a mean FAST score of 56.6 (±10.6), a value higher than that reported in this study. It was found that patients with a current job obtained lower FAST scores than those who were unemployed, and this difference was significant. This is different from what was reported in the Osorio-Martínez study,15 which found no significant difference in the FAST score according to occupation. These dissimilar findings may be explained by the characteristics of the patient population of the Hermilio Valdizán Hospital, which is a Ministry of Health hospital that attends chronic patients. No significant difference was found in the FAST score grouped by gender, although it has been reported in the literature that men with schizophrenia have slightly lower levels of functioning, and that women have higher levels of social support, which would improve their overall functioning.25,26

It was found that the total FAST score was negatively and significantly related to the length of time with the condition, which is similar to that reported by Osorio-Martínez,15 who found a direct relationship between the time with the condition and the total FAST score. That is, the longer the duration of the condition, the worse the overall functioning. However, other studies do not report the same findings. Apparently, there are no differences in the FAST score at different stages of the illness. Gazzi et al.27 found a mean of 31 FAST points in patients in the initial phase of their illness (first five years after diagnosis), and 34 points in the late phase (up to twenty years after diagnosis). Apparently, the duration of the illness, by itself, is not enough to classify people with schizophrenia since the effect on global functioning is only partial, maintaining a steady deterioration in functioning.27

A significant indirect relationship was found between the VLT-I and VLT-D and the total FAST score. The immediate (VLT-I) and delayed (VLT-D) verbal learning tests consist of learning new information, remembering that information learned over time, and recognising previously presented material.28 These results support what has been reported in other studies, which concluded that there is a relationship between poor performance in the VLT-I and VLT-D and poor global functioning.29

Processing speed (PST) was indirectly and significantly related to the total FAST score. Contrary to what was found in the present study, a recent meta-analysis, examining 19 studies with a total of 1095 patients and 324 controls, found that the PST of patients with schizophrenia was not associated with the duration of the illness or the level of education.30 Other studies have reported that a deficit in PST is related to a poor capacity in patients with schizophrenia to carry out their daily activities,31 keep their job,32 lead an independent life,33 and also to interact well socially.34

Of all the SCIP subtests, the strongest relationship was with the VMT. Working memory is commonly accepted to be a central component of cognition. However, its exact definition varies depending on the theoretical model followed (e.g. visual, auditory, spatial, semantic, motor, affective, contextual, etc.).35,36 In general, it refers to the ability to store, process and manipulate a limited amount of information for a short period.28 Similar to what is reported in this work, other studies have found that working memory has a relationship with global functioning, which could be useful for the daily interpersonal functioning of people with schizophrenia in social, work, education and community settings.35,37

In the multiple linear regression model, it was found that the variables that most influenced the FAST were the total SCIP score and the number of previous psychotic episodes. The SCIP total was the one that had the most influence on global functioning (Beta = −0.528), that is, lower levels of cognitive functioning are related to high levels of poor global functioning, similar to that reported in a meta-analysis.4 However, both variables explain 39% of the variance in global functioning. Therefore, not all global functioning in patients with schizophrenia could be explained by the variables analysed in this study, since stigma, culture and the society where the patient lives may also influence the final functional result.

The present study must be understood in the context of its potential methodological limitations. First, this was an exploratory pilot study, which was conducted in a single hospital, so these results cannot be generalised since we work with a small non-probabilistic population for convenience. However, despite the preliminary nature of these results due to the small sample size, the present study is heuristically significant as it provides data on the factors associated with global functioning among patients with schizophrenia in Peru. Second, being a cross-sectional study, we could not observe a causal relationship. Finally, the small size of the sample, and the fact that it is for convenience, does not allow us to ensure adequate power of the study.

ConclusionsOur results indicate that, in this sample of Peruvian patients with schizophrenia, the associated factors that most influence global functioning are cognitive functioning and the number of previous psychotic episodes. Future longitudinal studies should be conducted in larger patient samples, especially with a first psychotic episode, in order to look for a cause-effect relationship between global functioning and its associated factors in patients with schizophrenia.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animals. The author declares that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Data confidentiality. The author declares that the protocols at his work centre regarding the publication of patient data have been followed.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The author has obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. These documents are in the possession of the corresponding author.

FundingSelf-financed.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Huarcaya-Victoria J. Factores asociados al funcionamiento global en pacientes con esquizofrenia de un hospital general del Perú. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:252–259.