To determine the factors associated with impostor syndrome in medical students from six regions of Peru.

Material and methodsA multicentre, cross-sectional study was conduced on students from first to the sixth year in six Peruvian regions. Sociodemographic, academic, and psychological characteristics were included through the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and the Clance Imposter Phenomenon Scale. Generalised linear models were performed using crude and adjusted estimated prevalence ratios.

ResultsOf 2,231 medical students, 54.3% were female and 30.6% had the impostor phenomenon. An association was found between the PI and those who suffered from depression (aPR=1.51; 95%CI, 1.27–1.79), anxiety (aPR=2.25; 95%CI, 1.75–2.90), stress (aPR=1.37; 95%CI, 1.19–1.57), and being female (aPR=1.12; 95%CI, 1.01–1.26).

ConclusionsThree out of 10 medical students suffer from PI; having some level of depression, anxiety, stress, being a woman, and/or attending the fourth academic year were predisposing factors for their development.

Determinar los factores asociados con el síndrome del impostor (IP) en estudiantes de Medicina de 6 facultades peruanas.

Material y métodosMaterial y métodos Estudio multicéntrico transversal analítico realizado en estudiantes del primer al sexto año en 6 regiones peruanas. Se incluyeron características sociodemográficas, académicas y psicológicas mediante la escala de depresión, ansiedad y estrés, la escala de autoestima de Rosenberg y la escala del Fenómeno del Impostor de Clance. Los modelos lineales generalizados se construyeron mediante razones de prevalencia estimada brutas y ajustadas.

ResultadosDe 2.231 estudiantes de Medicina, el 54,3% eran mujeres y el 30,6% padecía IP. Se encontró asociación entre el IP y la depresión (RPa=1,51; IC95%, 1,27-1,79), la ansiedad (RPa=2,25; IC95%, 1,75-2,90), el estrés (RPa=1,37; IC95%, 1,19-1,57) y el sexo mujer (RPa=1,12; IC95%, 1,01-1,26).

ConclusionesDe cada 10 estudiantes de Medicina, 3 sufren IP; tener depresión, ansiedad o estrés, ser mujer y/o cursar el cuarto año fueron los factores predisponentes.

The impostor phenomenon (IP) or impostor syndrome is characterised by feelings of guilt about success experienced by people who are high achievers, and the inability to acknowledge it internally, added to strong feelings of phoniness.1 This phenomenon is experienced by individuals who doubt their own abilities, even though they are objectively capable and accomplished.2,3 People with IP are convinced that they are deceiving those around them about their abilities and are afraid of being exposed as frauds or impostors.3

Studies have attempted to determine the causes of IP and there is evidence that race, ethnicity and/or immigrant status can play a role in people who constantly consider themselves unworthy for the environment they find themselves in.4 The concept was originally defined with particular reference to women in the fields of science, technology, engineering, mathematics and even medicine.1,4 With regard to cultural factors, high levels of IP were found in students who were the first in their families to attend university and/or medical school, in addition to working or studying in another country.4,5 Being part of any higher education programme that included an apprentice level (student, resident intern, fellow), being surrounded by equally driven, outstanding individuals, and being constantly assessed (medical students during their clinical rotations) were triggers of IP in the different study populations.1–3

People with IP show a certain inability to delegate functions and make important decisions and tend to procrastinate about delivering projects, which prevents them from being team leaders, or they set impossible goals that end up lowering the morale of other employees, who feel they are being held back by poor leadership.4,6,7 This can make those suffering from IP even more incapable of making decisions or being team leaders, and more likely to develop chronic diseases, adjustment disorders (depression, anxiety) and, in certain cases, even suicidal tendencies.8,9

IP has now been seen in males and females3–5,8–11 and in different professions. Proportionally, however, it is medical professionals who suffer the most from this condition,4,5 which has also been reported in university students8,11 who are studying Human Medicine.8,9

Despite all this, even though IP is considered a psychological construct found in those who underestimate their abilities and skills, it has not yet been widely studied or documented.4 It has nonetheless been demonstrated that people affected by IP are incapable of internally acknowledging their accomplishments, while at the same time may magnify their failures.1,2,4 Accordingly, with this study we sought to quantify the prevalence of IP and determine the main associated factors in medical students at six medical schools in Peru.

Material and methodsStudy design and populationThis was an analytical cross-sectional study conducted on students from six medical schools: three of them at public universities, in the regions of Ica (Universidad Nacional San Luis Gonzaga), Ancash (Universidad Nacional del Santa) and Ucayali (Universidad Nacional de Ucayali); and three at private universities, in the regions of Lambayeque (Universidad San Martin de Porres Filial Norte), Junín (Universidad Continental) and Tacna (Universidad Privada de Tacna).

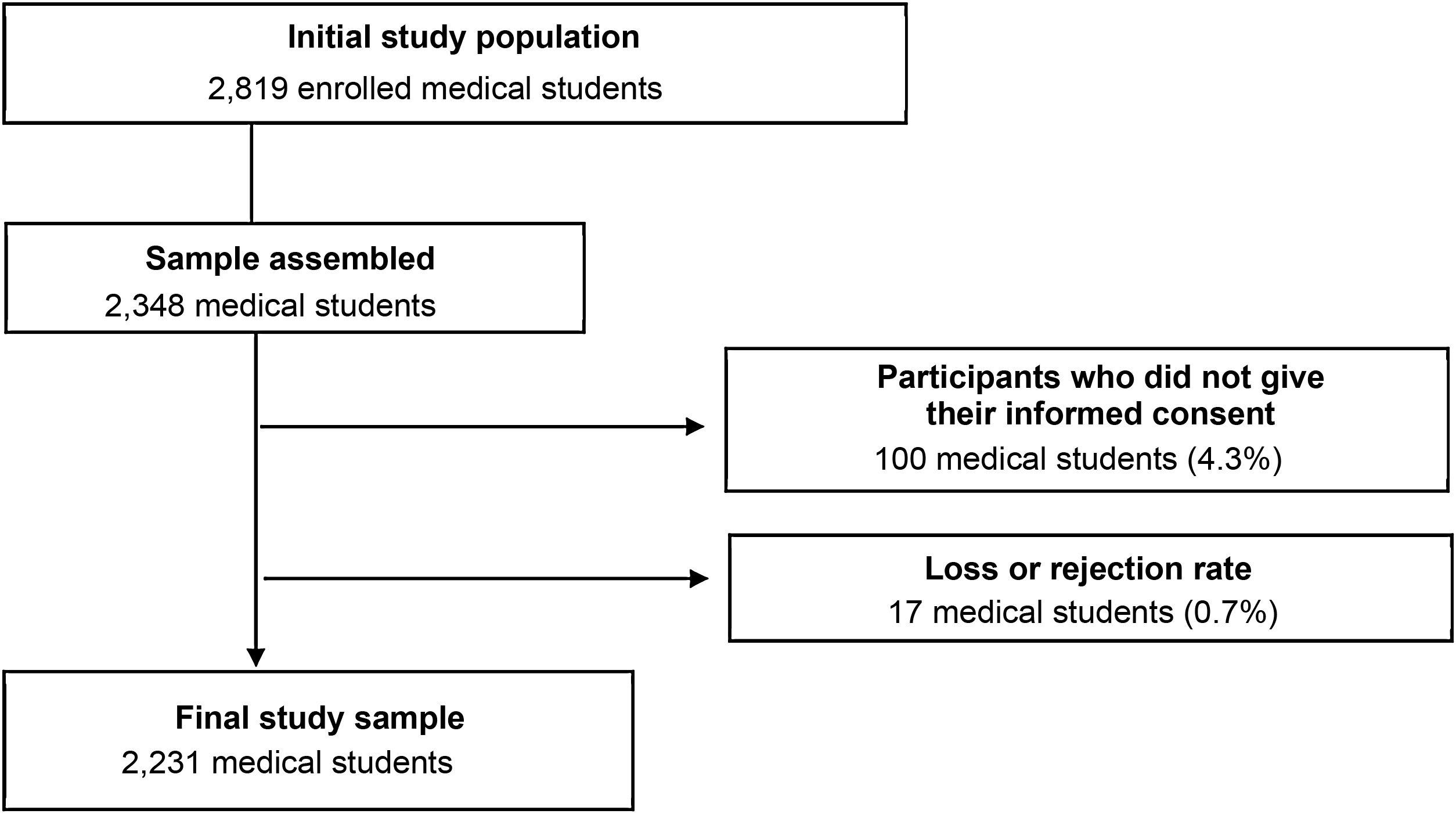

The initial sample size of 2819 medical students was calculated with a confidence level of 97% and a margin of error of 3%, which resulted in a sample size of 2348; later adjusted for possible losses of 20%. During the study, 100 surveys (4.3%) were discarded for not having a signed informed consent form and 17 (0.7%) could not be analysed because of incomplete data, leaving a final sample size of 2231 students (Fig. 1).

The list of those selected through stratified sampling considered all participants who were enrolled during the 2019-I academic semester corresponding to the first and sixth years of Medicine who did not have any problems for written communication and provided their informed consent. Incomplete surveys or those containing more than two items of data that made it impossible to analyse them were excluded.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Nacional de Ucayali (Ucayali, Peru). Authorisation to conduct the study was obtained from each of the Medical Schools participating in this study; during data collection, each interviewer proceeded to explain in detail to the selected students the purpose and main aim of the research, stressing its reliability and anonymity.

Instrument and variablesThe instrument consisted of a self-administered survey given out to each participant. The first section outlined the main information about the study and their informed consent. The second section concerned the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants: age; gender; marital status; people they are currently living with; and livelihood; as well as the average hours spent working. The academic characteristics assessed included: the academic year; the year of admission; approximate daily hours of study; and extracurricular activities and their type.

The psychological characteristics assessed in the third section were adjustment disorders, with the aim of detecting negative effects of anxiety, depression and stress, which include essential symptoms that make it difficult to relax, nervous tension, hyporexia, irritability and agitation.12 For this, we used the short version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21),13 which has a validated adaptation to Spanish in a similar university population,14 with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.85, 0.73 and 0.83 for the depression, anxiety and stress subscales, respectively. However, overall, the items making up the DASS-21 obtained α=0.91.14

The scale has 21 items with four alternatives on the Likert scale of 0 (rarely), 1 (sometimes), 2 (often) and 3 (almost always) to assess three parameters, including depression (items 3, 5, 10, 13, 16, 17 and 21), anxiety (items 2, 4, 7, 9, 15, 19 and 20) and stress (items 1, 6, 8, 11, 12, 14 and 18). The values for the depression scale range from normal (0–4 points), to mild depression (5–6 points), moderate (7–10 points), severe (11–13 points) and extremely severe (more than 14 points); anxiety levels range from normal (0–3 points), to mild anxiety (4–5 points), moderate (6–7 points), severe (8–9 points) and extremely severe (more than 10 points); and stress levels range from normal (0–7 points), to mild stress (8–9 points), moderate (10–12 points), severe (13–16 points) and extremely severe (more than 17 points).14

Self-esteem was also assessed using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES),15 which addresses aspects related to feeling competent in various aspects of life; the dimension on self-hatred uses insulting terms associated with sympathy with oneself16 in its version adapted to Spanish15–17 (α=0.75).17 The scale consists of 10 items about the person's feelings about themselves, with the first five positive statements (items 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5), on a 4-point Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (agree) and 4 (strongly agree). The score is inverted for negative statements (items 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10). The values on the scale range from low self-esteem (<25 points) to normal (25–35 points) to high (>35 points).17

IP was assessed using the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS),1,18 which determines the clarity of self-concept, components of social self-esteem and concern for having succeeded by chance.18 Its original version has α=0.9618; the CIPS version adapted to Spanish19 had a test of sphericity and a significant sampling adequacy measure (0.89); the reliability of the instrument showed α=0.92. However, as the scale was not adapted to a population such as that of our study, the authors carried out a pilot test on 280 students from one of the study sites in the Ucayali region during the 2018 academic year. This enabled us to determine an internal consistency with α=0.91, in addition to the permanence of all the items of the instrument, as they did not modify the final construct.

The CIPS is therefore made up of 20 items rated using a 5-point Likert scale: 1 (not at all true), 2 (rarely true), 3 (sometimes true), 4 (often true) and 5 (very true). The sum of the 20 items provides the score; <62 indicates absence of IP and ≥62 is defining of IP.19,20

Data analysisThe data collected in the survey were recorded on an Excel 2013 spreadsheet, entered on two separate occasions by different people to verify the quality of the data. Data were analysed with the STATA version 14 statistical package; the qualitative variables are presented as frequency and percentage, and the quantitative variables as median [interquartile range] when distribution is not normal, after checking using the skewness and kurtosis test, with a p-value <0.05.

With regard to the inferential statistics for the qualitative variables, the DASS-21 variables were dichotomised, considering as affected by the condition those who had some degree of depression, anxiety or stress according to each of the subscales. Lastly, we used this recoding in order to be able to use generalised models, applying logistic regression for both the crude (crude prevalence ratios [PR]) and adjusted (adjusted prevalence ratios [APR]) analysis; a p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

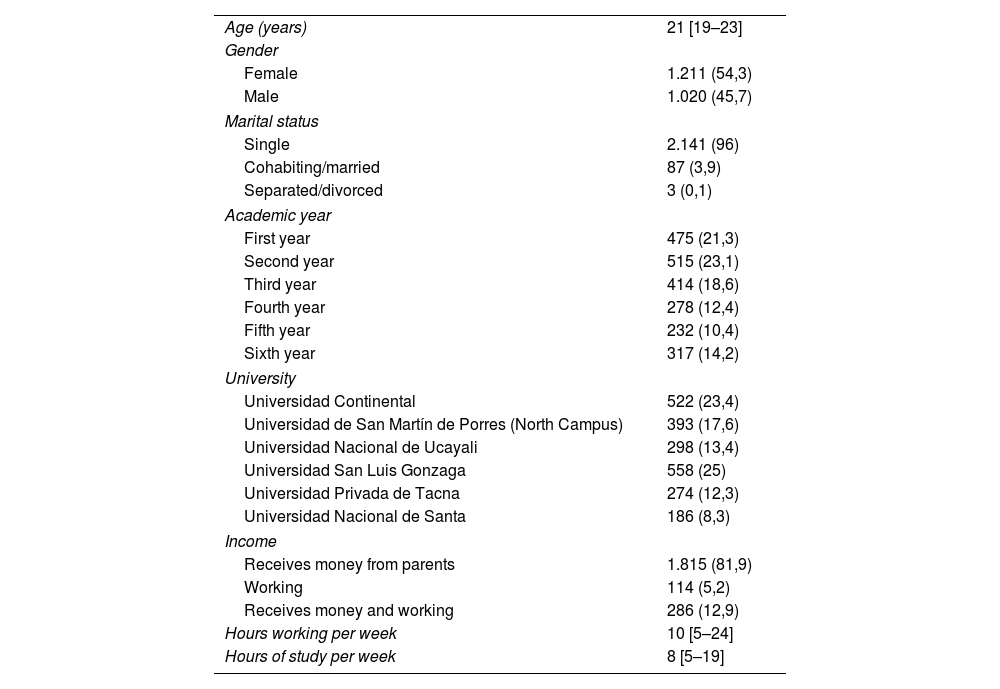

ResultsThe study population was made up of 2231 Human Medicine students from six Peruvian universities; median age was 21 years [19–23]; 96% of the participants (2140) stated that they were single (Table 1).

General characteristics of the population studied.

| Age (years) | 21 [19–23] |

| Gender | |

| Female | 1.211 (54,3) |

| Male | 1.020 (45,7) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 2.141 (96) |

| Cohabiting/married | 87 (3,9) |

| Separated/divorced | 3 (0,1) |

| Academic year | |

| First year | 475 (21,3) |

| Second year | 515 (23,1) |

| Third year | 414 (18,6) |

| Fourth year | 278 (12,4) |

| Fifth year | 232 (10,4) |

| Sixth year | 317 (14,2) |

| University | |

| Universidad Continental | 522 (23,4) |

| Universidad de San Martín de Porres (North Campus) | 393 (17,6) |

| Universidad Nacional de Ucayali | 298 (13,4) |

| Universidad San Luis Gonzaga | 558 (25) |

| Universidad Privada de Tacna | 274 (12,3) |

| Universidad Nacional de Santa | 186 (8,3) |

| Income | |

| Receives money from parents | 1.815 (81,9) |

| Working | 114 (5,2) |

| Receives money and working | 286 (12,9) |

| Hours working per week | 10 [5–24] |

| Hours of study per week | 8 [5–19] |

Values are expressed as n (%) or median [interquartile range].

A total of 72.8% (1496) stated that they lived with a family member (parents, siblings and/or aunts and uncles); 19.2% (394) lived alone; and 3.2% (66) with their partner. Some 12.9% (286) stated that they received money from their relatives and from working. A majority 56.4% (1244) stated that they were not satisfied with their academic performance, and only 43.6% (960) did some type of extracurricular activity as part of their university life: 43% (480) did some type of sport; 24.4% (239) had some involvement in art and/or music; and 21% (234) and 15.7% (176) belonged to the student union or a scientific society, respectively (Table 1).

According to the DASS-21, 60.7% (1355) did not have any degree of stress. However, 17.8% (398) reported mild levels of stress, 14.2% (316) moderate, 5.6% (125) severe and 1.7% (37) extremely severe. In terms of anxiety, 32.9% (735) had none, but 15.8% (352) reported mild levels of anxiety, 18.9% (422) moderate, 13.8% (307) severe and 18.6% (415) extremely severe. Last of all, 50.8% (1133) reported some degree of depression, while 14.7% (327) had mild depression, 23.2% (518) moderate, 7.8% (174) severe and 3.5% (79) extremely severe (Fig. 2).

From the RSES, we determined that 22.3% (497) of the participants had normal levels of self-esteem, while 75.3% (1681) had low self-esteem and only 2.4% (53), high self-esteem (Fig. 2). Of those with low self-esteem, 22.1% (372) were second-year students and 19.5% (328) first-year students. In contrast, 28.3% of fifth-year students (15) had high self-esteem. A statistically significant association (p<0.05) was found using the χ2 test between the academic year and the RSES.

The CIPS found that only 30.6% of the students (682) suffered from IP (Fig. 3). In addition, it was found that during the second, fourth and third years, 20.8% (142), 19.9% (136) and 19.7% (134), respectively, suffered from IP (association between academic year and the CIPS by χ2, p<0.05).

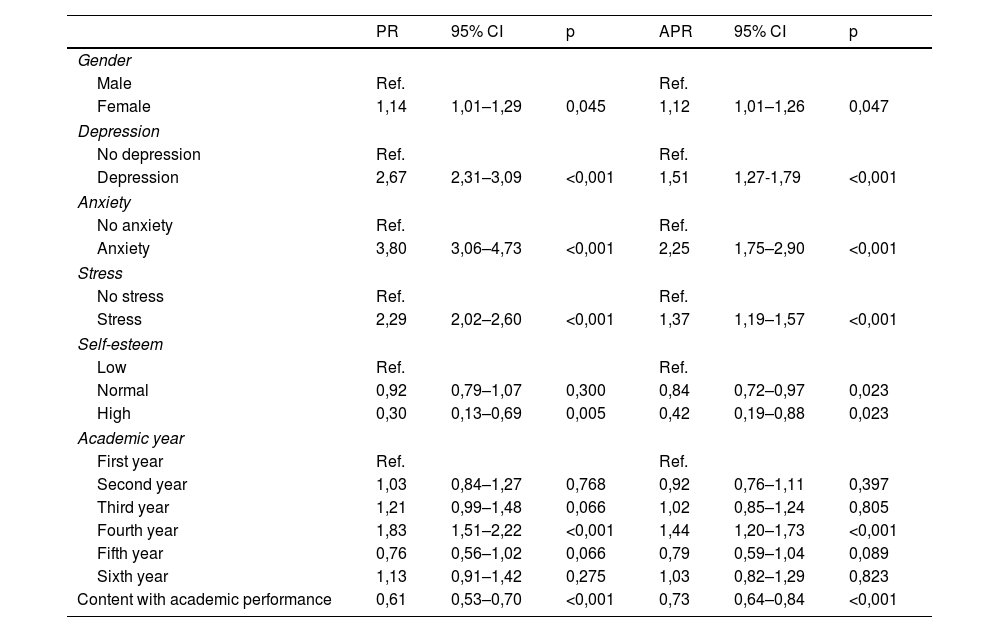

The bivariate analysis found that being female, being in the fourth year and having some degree of depression, anxiety or stress meant a likelihood 1.14 times greater of suffering from IP than those who did not meet any of these conditions (PR=1.14; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.01−1.29), 1.83 (PR=1.83; 95% CI, 1.51−2.22), 2.67 (PR=2.67; 95% CI, 2.31−3.09), 3.80 (PR=3.80; 95% CI, 3.06−4.73) and 2.29 (PR=2.29; 95% CI, 2.02−2.60). It was also found that those who had high levels of self-esteem were less likely to have IP (Table 2).

Bivariate and multivariate analyses of the factors associated with impostor phenomenon in medical students.

| PR | 95% CI | p | APR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Female | 1,14 | 1,01–1,29 | 0,045 | 1,12 | 1,01–1,26 | 0,047 |

| Depression | ||||||

| No depression | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Depression | 2,67 | 2,31–3,09 | <0,001 | 1,51 | 1,27-1,79 | <0,001 |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| No anxiety | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Anxiety | 3,80 | 3,06–4,73 | <0,001 | 2,25 | 1,75–2,90 | <0,001 |

| Stress | ||||||

| No stress | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Stress | 2,29 | 2,02–2,60 | <0,001 | 1,37 | 1,19–1,57 | <0,001 |

| Self-esteem | ||||||

| Low | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Normal | 0,92 | 0,79–1,07 | 0,300 | 0,84 | 0,72–0,97 | 0,023 |

| High | 0,30 | 0,13–0,69 | 0,005 | 0,42 | 0,19–0,88 | 0,023 |

| Academic year | ||||||

| First year | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Second year | 1,03 | 0,84–1,27 | 0,768 | 0,92 | 0,76–1,11 | 0,397 |

| Third year | 1,21 | 0,99–1,48 | 0,066 | 1,02 | 0,85–1,24 | 0,805 |

| Fourth year | 1,83 | 1,51–2,22 | <0,001 | 1,44 | 1,20–1,73 | <0,001 |

| Fifth year | 0,76 | 0,56–1,02 | 0,066 | 0,79 | 0,59–1,04 | 0,089 |

| Sixth year | 1,13 | 0,91–1,42 | 0,275 | 1,03 | 0,82–1,29 | 0,823 |

| Content with academic performance | 0,61 | 0,53–0,70 | <0,001 | 0,73 | 0,64–0,84 | <0,001 |

APR: adjusted prevalence ratio; PR: crude prevalence ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

Finally, in the multivariate analysis, after an adjustment was made for the variables described, we were able to determine that the participants who had depression had a 51% higher likelihood of suffering from IP (APR=1.51; 95% CI, 1.27−1.79), those with anxiety, 125% higher (APR=2.25; 95% CI, 1.75−2.90) and those with stress, 37% higher (APR=1.37; 95% CI, 1.19−1.57). Females had a 12% greater predisposition to IP (APR=1.12; 95 % CI, 1.01−1.26) than males. Students with high self-esteem and those who were content with their academic performance showed 58% (APR=0.42; 95% CI, 0.19−0.88) and 27% (APR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.64−0.84) less likelihood of IP, respectively (Table 2).

DiscussionThe prevalence of IP was higher in women. It has been considered that males tend to have more confidence in their intellectual capacity than women. However, adhering to this social concept allows women to be thought of as incapable and, if they show they are not, that they have lost their femininity, thereby devaluing their own success by seeking to reduce this polarity.12 For that reason, “success” is more difficult for them to assess and achieve because of different social expectations; women tend to show the need to explain their accomplishments by attributing their intelligence and/or giving credit to external factors beyond their own capabilities.2

Previous studies have managed to define certain differences in the prevalence of IP according to gender, and men show a greater tendency to these feelings.21–23 These studies have also shown that men do not tend to openly acknowledge IP, as they tend to protect themselves from this type of emotion.24 As such, for fear of presenting an atypical masculine image or a position that could question their sexuality, they tend to put on the appearance of indifference so as not to feel inadequate in the society around them.24 This explains why IP, initially observed in women, is now acknowledged to show mixed trends in terms of its distribution by gender.3–5,9–11,25–27 However, IP is still considered one of the biggest challenges facing women in medicine,28 in line with research that shows the relationship between IP and less career planning and professional effort, in addition to motivation to pursue and take on leadership roles.29

Our study found that only three in 10 students suffered from IP, but that there was an association between being a fourth-year student and a greater tendency towards IP. After consulting different studies,1–5,8,9 we are able to conclude that a transition in the academic development of any student, the assignment of new duties, the aim to excel, being part of any programme involving continuous and scaled learning, and being assessed are also determining factors in the development of IP.1 Here in Peru, most schools of Human Medicine begin their hospital practices in the fourth year, which means a change in both methodology and teaching and constant assessments for undergraduate students with patients, and this may explain the disproportionate development of IP among fourth-year students.

Being content with academic performance and/or having high levels of self-esteem have a negative correlation with IP, as individuals with high self-esteem attribute their achievements to their own abilities, their own intelligence and/or competence.30–32 Some authors31,32 recommend having, and even believe it necessary to have, high levels of self-esteem combined with certain IP characteristics, so that future doctors practice medicine in a proper, sustainable and, to a certain extent, healthy manner, as this combination could provide the necessary tools for diagnosing and treating patients with both caution and care.

Depression levels increased the likelihood of having IP by 56%. However, these symptoms are not always concomitant, and various authors have stated that symptoms experienced may be similar to mild depressive disorders.33,34 Patients with IP and some degree of depression tend to be more critical and harder on themselves and they mask any depressive symptoms, all of which diminishes their performance and their ability to achieve their goals and improve productivity, and leaves them unable to perceive success in their achievements.34

People with IP may not achieve their goals because they are enveloped in a vicious circle of anxiety attacks that manifest on a daily basis. Stress similarly increased the likelihood of suffering IP by 39%. This is due to a persistent struggle to prove that they should be the best in their class, disregarding their own talents and belittling their own ability. Last of all, there is an association between anxiety-related symptoms and IP35; the constant assessments, the fear of failure, the doubts generated, apprehension, the lack of confidence and the fear of being exposed as a fraud36,37 provoke and encourage fervent preparation for success and perfectionism, but in the end de-legitimise their accomplishments, and this becomes a never-ending vicious circle.35–37

Our study has certain limitations, such as access to the different schedules of all the participants selected at the universities, and their commitment to provide their informed consent, in addition to not being able to carry out a case-control and/or longitudinal study to determine the causality of the IP in medical students.

ConclusionsThree in 10 medical students suffer from IP. Suffering some degree of depression, anxiety or stress and being a woman and/or a fourth-year student are all predisposing factors for IP. We also identified that being content with academic performance and having high self-esteem are protective factors against IP among medical students.

We recommend expanding the study nationwide and, given the hostile environment they have to deal with in hospitals, including all students of health sciences. Moreover, sampling techniques should be applied that allow data to be extrapolated to the real situations experienced by these Peruvian health science students.

We propose expanding the research to a case-control study to determine the risk factors for IP more accurately, as well as a longitudinal study to detect possible causality between other variables in addition to the association with the number of years at university.

As a result of our study, we recommend providing advice, counselling and psychological support to students throughout their university course, to enable early detection of psychological conditions that may affect their performance, prevent them from fulfilling their full academic potential and end up triggering the development of IP.

FundingThis research was self-financed by all the authors.

Conflicts of interestThe pilot for this study was part of Dr Jennifer Vilchez-Cornejo's thesis entitled "Factores asociados al síndrome del impostor en estudiantes de medicina de la Universidad Nacional de Ucayali, 2018" ["Factors associated with impostor syndrome in medical students at the National University of Ucayali, 2018"], defended in 2019 at Universidad Nacional de Ucayali.

The authors would like to thank university student Julia García Gutiérrez, who contributed to the initial versions of the article and performed data collection.