Mild cognitive impairment produces slight cognitive and motor disturbances without affecting daily life during aging, however, if this symptomatology is not controlled, the speed of deterioration can increase, and even some cases of dementia can appear in the elderly population.

ObjectiveTo describe non-pharmacological therapies that seek to prevent, control and reduce the symptoms of mild cognitive impairment.

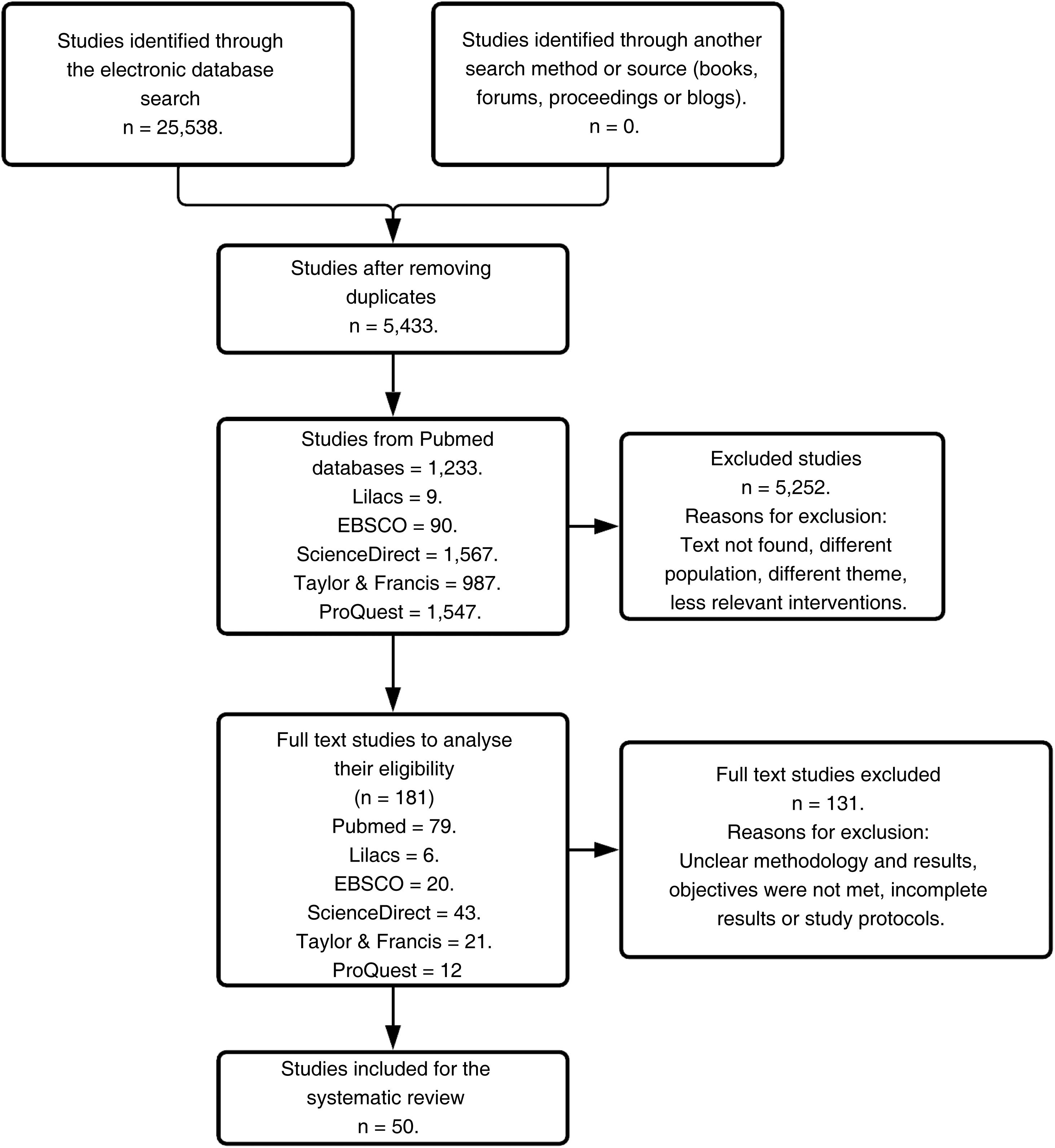

MethodsAn initial search was carried out in the databases of PubMed, Lilacs, EBSCO, ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis and ProQuest. The results found were filtered through the PRISMA system and biases evaluated using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.

ResultsFour categories of non-pharmacological therapies were created, using 50 articles found in the search, which contribute to controlling and improving cognitive and motor areas, in order to reduce the symptoms presented by mild cognitive impairment. The treatments have different methods, instruments and objectives, so that no meta-analysis of the studies could be performed. In addition, limitations related to the sample, the effectiveness of the results and the methodological quality were found.

ConclusionsIt was found that non-pharmacological therapies prevent, improve and control the symptoms caused by mild cognitive impairment, however, it is necessary to carry out more studies with better methodologies to corroborate these results.

El deterioro cognitivo leve produce ligeras perturbaciones cognitivas y motoras que no afectan a la vida cotidiana durante el envejecimiento; sin embargo, de no controlarse este síntoma, puede aumentar la velocidad del deterioro e incluso pueden manifestarse algunos casos de demencia en los adultos mayores.

ObjetivoDescribir los tratamientos no farmacológicos para prevenir, controlar y reducir los síntomas del deterioro cognitivo leve.

MétodosSe realizó una búsqueda inicial en las bases de datos PubMed, Lilacs, EBSCO, ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis y ProQuest. Los resultados se filtraron a través del sistema PRISMA y se evaluaron los sesgos mediante el Manual Cochrane de revisiones sistemáticas de intervenciones.

ResultadosSe construyeron 4 categorías de tratamientos no farmacológicos con los 50 artículos encontrados en la búsqueda, las cuales contribuyen a controlar y mejorar áreas cognitivas y motoras con el fin de reducir los síntomas del deterioro cognitivo leve. Los tratamientos tienen métodos, instrumentos y objetivos diferentes, por lo que no se pudo realizar un metanálisis de los estudios. Asimismo se encontraron limitaciones relacionadas con la muestra, la efectividad de los resultados y la calidad metodológica.

ConclusionesSe encontró que los tratamientos no farmacológicos previenen, mejoran y controlan los síntomas del deterioro cognitivo leve, pero es necesario realizar más estudios con mejores metodologías que corroboren estos resultados.

Ageing forms part of the human life cycle, and presents a variety of cognitive, behavioural and physiological changes that result in reduced skills and difficulty in performing different everyday tasks, in addition to the possible presence of neurodegenerative diseases caused by age, genetic factors, or accidents which affect the brain directly or indirectly.1

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is one of the most frequent disorders caused mainly by ageing; it is known as an intermediate cognitive state, between normal ageing and dementia,2 which gives rise to mild disturbances in different areas, such as memory, attention. language, and executive and visuospatial functions.2 It is worth clarifying, however, that these symptoms need not interfere with the individual's everyday life.3

On other hand, MCI may be a predictor or precursor of chronic neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia,2 that is, there is a risk of the onset of progressive symptoms that worsen over time, leading to concerns about loss of functionality and cognitive skills in elderly adults; hence the need for early intervention and management of these symptoms.

Moreover, there is clearly a lack of effective medicinal treatments that prevent or diminish MCI,4 for which reason a number of randomised clinical trials evaluating non-pharmacological therapies are being conducted, with the aim of identifying factors that may reduce or control the symptoms of these cognitive disturbances.

The purpose of this systematic review is to identify non-pharmacological treatments aimed at preventing, reducing or controlling the characteristic symptoms of MCI and, thus, to analyse the beneficial effects on the individual's well-being, with a view to preventing the growing number of elderly adults suffering from dementia.

MethodsA systematic search was performed of the literature between February and June 2021, using the following databases: PubMed, Lilacs, EBSCO, ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis and ProQuest. The inclusion criteria employed were: randomised, controlled, crossover and pilot clinical trials published between 2011 and 2021, with an elderly adult population, which analyse the different treatment which help to reduce, prevent or control MCI: the electronic version thereof also had to be available in Spanish or English.

The keywords for the search process were: "mild cognitive impairment'', "alternative therapies'', "prevention" and "elderly adult'', which were filtered in English and Spanish in order to not exclude any articles relevant for this study.

First of all, articles were selected and discarded by means of observation, which took into account the characteristics and information provided in the title and abstract with the aim of identifying whether they had the content necessary for the review. They were then incorporated into an Excel sheet, in which the study data (such as title, year, sample, treatment type, study type and other pertinent information) were grouped together in order decide whether they met the inclusion criteria).

The initial search found 25,538 articles relating to MCI, but after eliminating the duplicates (using Mendeley, version 1.19.8, software developed by Elsevier), verifying whether they had the full text, checking the language, and examining whether they were randomised clinical trials, 25,357 studies were excluded, leaving 181 studies, which were analysed to determine their relevance. Other exclusion factors were also found: scant relevance in content, errors in methods employed, unspecified sample or time, and proposed objectives not met, with 50 articles finally included (Fig. 1).

A total of 34 studies from PubMed, two from Lilacs, two from EBSCO, seven from ScienceDirect, two from Taylor & Francis and three from ProQuest were incorporated, in both English and Spanish. It is important to stress that it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis or statistical grouping of the data, given that there are a variety of articles with different types of treatments, interventions, and objectives set, as a result of which a high degree of heterogeneity is evident, precluding the use of these tools.

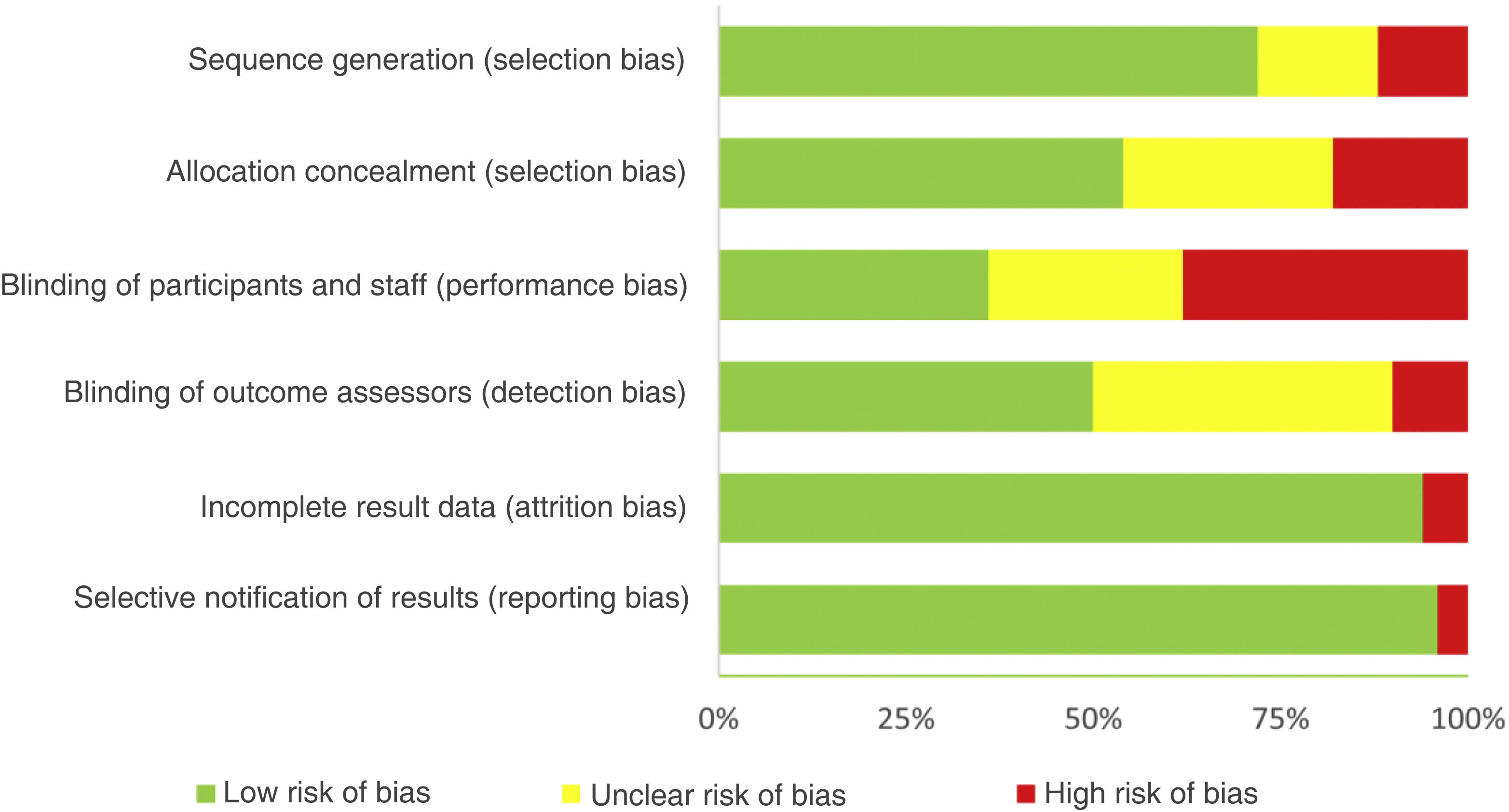

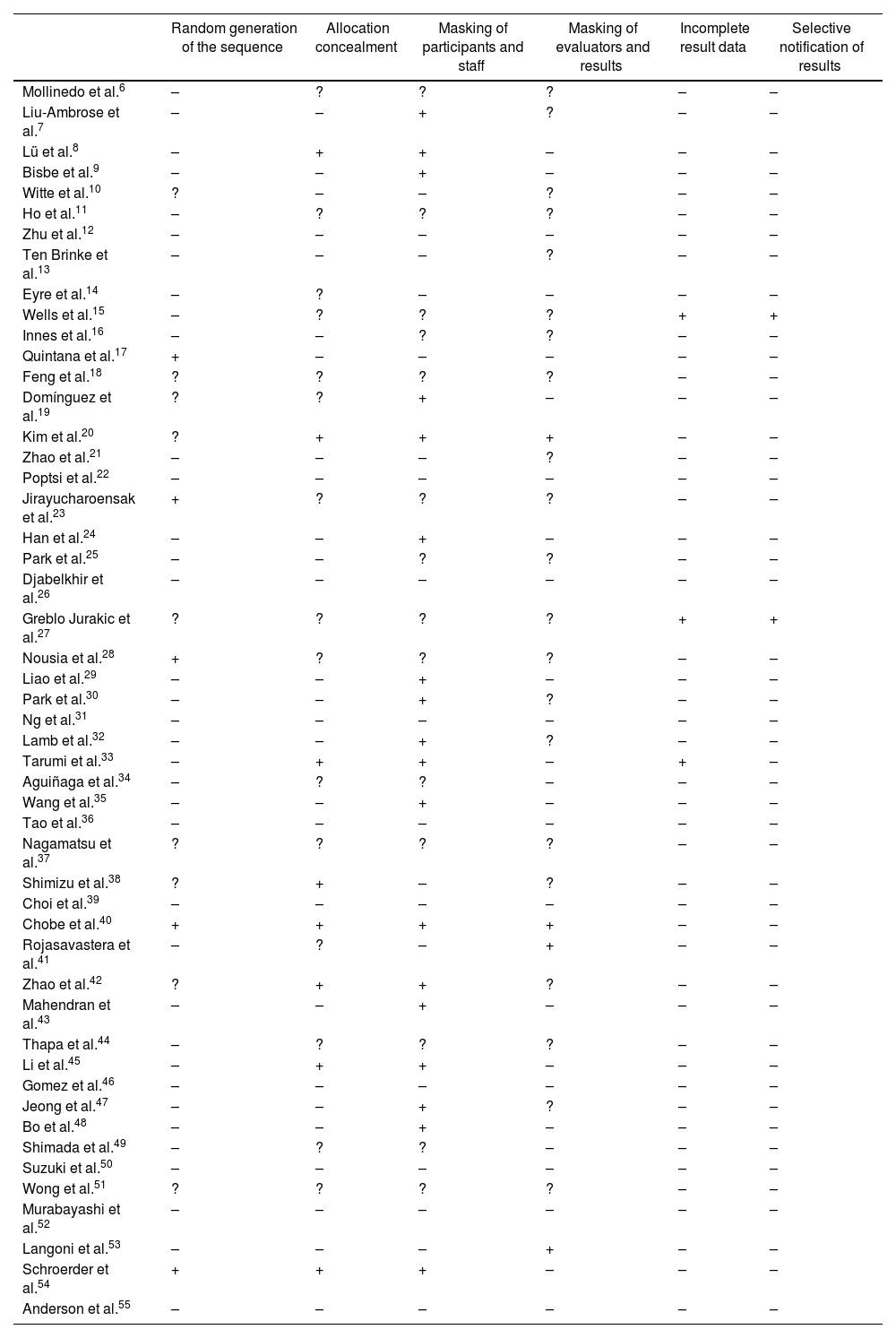

An assessment of risk of bias was conducted using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (high, low, or imprecise)5 (Fig. 2) (Appendix A).

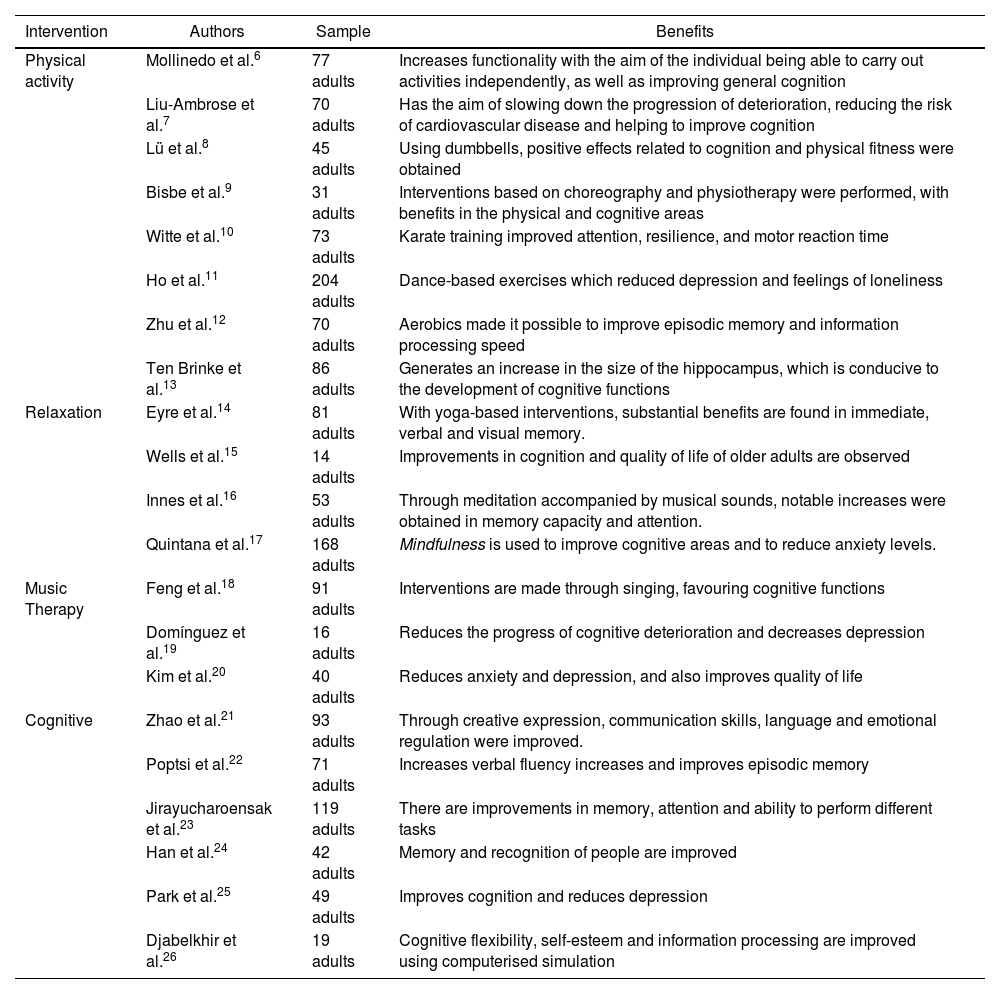

ResultsAfter performing the systematic search for articles, 50 randomised clinical trials were incorporated into the review. These were grouped by interventions or treatments, and the most relevant were described (Table 1). Appendix A and Fig. 2 show the qualification of all studies performed with the Cochrane Handbook. It is important to stress that the population type for each of the studies is the same, since they were in late adulthood.

Psychotherapies in mild cognitive impairment with most relevant findings identified during the review.

| Intervention | Authors | Sample | Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity | Mollinedo et al.6 | 77 adults | Increases functionality with the aim of the individual being able to carry out activities independently, as well as improving general cognition |

| Liu-Ambrose et al.7 | 70 adults | Has the aim of slowing down the progression of deterioration, reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease and helping to improve cognition | |

| Lü et al.8 | 45 adults | Using dumbbells, positive effects related to cognition and physical fitness were obtained | |

| Bisbe et al.9 | 31 adults | Interventions based on choreography and physiotherapy were performed, with benefits in the physical and cognitive areas | |

| Witte et al.10 | 73 adults | Karate training improved attention, resilience, and motor reaction time | |

| Ho et al.11 | 204 adults | Dance-based exercises which reduced depression and feelings of loneliness | |

| Zhu et al.12 | 70 adults | Aerobics made it possible to improve episodic memory and information processing speed | |

| Ten Brinke et al.13 | 86 adults | Generates an increase in the size of the hippocampus, which is conducive to the development of cognitive functions | |

| Relaxation | Eyre et al.14 | 81 adults | With yoga-based interventions, substantial benefits are found in immediate, verbal and visual memory. |

| Wells et al.15 | 14 adults | Improvements in cognition and quality of life of older adults are observed | |

| Innes et al.16 | 53 adults | Through meditation accompanied by musical sounds, notable increases were obtained in memory capacity and attention. | |

| Quintana et al.17 | 168 adults | Mindfulness is used to improve cognitive areas and to reduce anxiety levels. | |

| Music Therapy | Feng et al.18 | 91 adults | Interventions are made through singing, favouring cognitive functions |

| Domínguez et al.19 | 16 adults | Reduces the progress of cognitive deterioration and decreases depression | |

| Kim et al.20 | 40 adults | Reduces anxiety and depression, and also improves quality of life | |

| Cognitive | Zhao et al.21 | 93 adults | Through creative expression, communication skills, language and emotional regulation were improved. |

| Poptsi et al.22 | 71 adults | Increases verbal fluency increases and improves episodic memory | |

| Jirayucharoensak et al.23 | 119 adults | There are improvements in memory, attention and ability to perform different tasks | |

| Han et al.24 | 42 adults | Memory and recognition of people are improved | |

| Park et al.25 | 49 adults | Improves cognition and reduces depression | |

| Djabelkhir et al.26 | 19 adults | Cognitive flexibility, self-esteem and information processing are improved using computerised simulation |

Four categories of non-pharmacological treatments that contribute to prevention and to increasing diminished abilities owing to MCI in the elderly adult; physical activities, relaxation, music therapy, and cognitive intervention, were found. Therefore, there is a variety of results in studies that aimed to improve, prevent, or reverse the symptoms of this condition; on the other hand, the mean population sample used was 87,64 subjects.

The treatments that were most often mentioned and used in the review were those based on physical activities, which included different methods or exercises, as well as cognitive interventions, for which there are also a variety of programmes, platforms, or games.

The risks of bias found in the studies are related to the masking of participants, staff, or evaluators. It should be pointed out that, although not all the articles are affected by this problem, it was apparent in many of them; additionally, some studies conducted the randomisation process in an ill-advised manner, according to the Cochrane Handbook5 (Fig. 2 and Appendix A).

DiscussionThis study shows that the use of non-pharmacological treatments has positive impacts on elderly adults and is beneficial in aspects of cognitive and executive function, such as memory, attention, processing speed, mood, balance and strength, among other objectives to prevent, treat, or improve the symptoms of MCI. Moreover, interventions with physical exercise and computerised cognitive training are prominent, as they were the most commonly implemented in the studies.

Nonetheless, the studies included in the review do have discernible limitations; one of the most salient is the small number of participants, as illustrated in Table 1, which means that the samples are unrepresentative and do not allow the efficacy of the results obtained in this population to be validated. In turn, in the studies conducted by Jirayucharoensak et al.,23 Ten Brinke et al.,13 Kim et al.20 and Greblo Jurakic et al.27 it was found that, in most cases, the samples comprised only women, which raises uncertainty as to whether the findings may also be evident in elderly men. Moreover, Nousia et al.28 included more participants in the intervention group than in the control group, owing to which the effects obtained cannot be properly compared.

Conversely, the studies by Liao et al.,29 Poptsi et al.,22 Liu-Ambrose et al.,7 Eyre et al.,14 Kim et al.20 and Nousia et al.28 made no long-term evaluations of the results obtained, so it is not clear whether they are sustainable. On the contrary, cognitive training treatment with creative expression21 only presented long-term results, and the intervention needs to be constant to ensure that the benefits of these treatments are not impaired.

Additionally, in three articles, no benefits in the cognitive area are evident, as they focus solely on strengthening participants' motor function.30,31 Consequently, Liu-Ambrose et al.7 and Lamb et al.32 determined that their results could only be applicable in MCI, since they did not present the same effect in severe stages of the condition. However, Park et al.30 recommend further examining virtual reality-based computerised cognitive training in order to benefit the population with dementia.

Moreover, some studies have specific limitations. In the case of Tarumi et al.,33 results were not apparent for all participants; the dance-based intervention generated pain in the elderly adults’ limbs, in addition to which the recommended application time is not indicated34; in the music-based intervention of Feng et al.,18 similar results were obtained in the intervention and control groups, so it is not possible to verify the effectiveness of its benefits.

The biases of the review process are due principally to the variability of the studies included, as they render statistical analysis impossible and limit the correlations. Also incorporated were randomised pilot clinical trials, which can give rise to problems as they are smaller scale studies. On the other hand, the search for and selection of articles was only in English and Spanish.

ConclusionsDifferent non-pharmacological treatments were identified that generate positive effects on the health of the individual, which prevent, reduce or control the symptoms of MCI. The majority of these studies identified notable improvements in cognition, but numerous constraints related with time, sample size and non-compliance with objectives were evident.

The use of these treatments is recommended to reduce the number of individuals diagnosed with dementia, as well as to improve the well-being of elderly adults, although it is important to conduct large-scale studies to corroborate the information of the pilot studies included, as well as to provide more rigorous methods, since some studies have major limitations or unclear results.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

| Random generation of the sequence | Allocation concealment | Masking of participants and staff | Masking of evaluators and results | Incomplete result data | Selective notification of results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mollinedo et al.6 | – | ? | ? | ? | – | – |

| Liu-Ambrose et al.7 | – | – | + | ? | – | – |

| Lü et al.8 | – | + | + | – | – | – |

| Bisbe et al.9 | – | – | + | – | – | – |

| Witte et al.10 | ? | – | – | ? | – | – |

| Ho et al.11 | – | ? | ? | ? | – | – |

| Zhu et al.12 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ten Brinke et al.13 | – | – | – | ? | – | – |

| Eyre et al.14 | – | ? | – | – | – | – |

| Wells et al.15 | – | ? | ? | ? | + | + |

| Innes et al.16 | – | – | ? | ? | – | – |

| Quintana et al.17 | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| Feng et al.18 | ? | ? | ? | ? | – | – |

| Domínguez et al.19 | ? | ? | + | – | – | – |

| Kim et al.20 | ? | + | + | + | – | – |

| Zhao et al.21 | – | – | – | ? | – | – |

| Poptsi et al.22 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Jirayucharoensak et al.23 | + | ? | ? | ? | – | – |

| Han et al.24 | – | – | + | – | – | – |

| Park et al.25 | – | – | ? | ? | – | – |

| Djabelkhir et al.26 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Greblo Jurakic et al.27 | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + |

| Nousia et al.28 | + | ? | ? | ? | – | – |

| Liao et al.29 | – | – | + | – | – | – |

| Park et al.30 | – | – | + | ? | – | – |

| Ng et al.31 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lamb et al.32 | – | – | + | ? | – | – |

| Tarumi et al.33 | – | + | + | – | + | – |

| Aguiñaga et al.34 | – | ? | ? | – | – | – |

| Wang et al.35 | – | – | + | – | – | – |

| Tao et al.36 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nagamatsu et al.37 | ? | ? | ? | ? | – | – |

| Shimizu et al.38 | ? | + | – | ? | – | – |

| Choi et al.39 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Chobe et al.40 | + | + | + | + | – | – |

| Rojasavastera et al.41 | – | ? | – | + | – | – |

| Zhao et al.42 | ? | + | + | ? | – | – |

| Mahendran et al.43 | – | – | + | – | – | – |

| Thapa et al.44 | – | ? | ? | ? | – | – |

| Li et al.45 | – | + | + | – | – | – |

| Gomez et al.46 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Jeong et al.47 | – | – | + | ? | – | – |

| Bo et al.48 | – | – | + | – | – | – |

| Shimada et al.49 | – | ? | ? | – | – | – |

| Suzuki et al.50 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Wong et al.51 | ? | ? | ? | ? | – | – |

| Murabayashi et al.52 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Langoni et al.53 | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Schroerder et al.54 | + | + | + | – | – | – |

| Anderson et al.55 | – | – | – | – | – | – |