Male chauvinism is rooted in certain populations, but it has not been measured among those who will be responsible for healthcare.

ObjectiveTo determine the factors associated with male chauvinism among the medical students of 12 Peruvian universities.

MethodsCross-sectional multicentre analytical study, with previously collected data, which used validated tests to measure male chauvinism and strong religious beliefs. In addition, other social and educational factors were analysed and the data was crossed. Descriptive and analytical statistics were obtained.

ResultsIn the multivariate analysis, we found an association between male chauvinism and religious non-believers (RP=1.88; 95% CI, 1.47–2.40), as well as being female (RP=0.35; 95% CI, 0.27–0.46). Of the 12 universities evaluated, the least chauvinistic university was in Lima. Using this university as a comparison category, the statistically more chauvinistic universities were a private university in Chiclayo (α=3.63; p<0.001), followed by a university in Huancayo (α=3.20; p=0.001), Huancayo national university (α=2.79; p<0.001) and the public university of Ica (α=2.32; p=0.006); the crossed data were adjusted for age.

ConclusionsIt was found that male chauvinism is greater among non-religious believers, men and in some universities, with a predominance of universities in the central highlands of Peru or that had migrants from the mountains. This is important, since it gives us an overview about this trait in those who will be responsible for the future healthcare of Peruvians.

El machismo está arraigado en ciertas poblaciones, pero no se ha medido esto entre los que se encargarán de la atención de la salud.

ObjetivoDeterminar los factores asociados con el machismo entre los estudiantes de Medicina de 12 universidades peruanas.

MétodosEstudio transversal analítico de tipo multicéntrico, con datos recogidos previamente, en el que se usaron tests validados para la medición del machismo y la religiosidad; además, se indagaron otras características sociales y educativas y se cruzaron los datos. Se obtuvieron estadísticos descriptivos y analíticos.

ResultadosEn el análisis multivariable, se encontró asociación entre ser machista y no creyente (RP=1,88; IC95%, 1,47-2,40), así como ser mujer (RP=0,35; IC95%, 0,27-0,46). De las 12 universidades evaluadas, la universidad menos machista fue una particular en Lima. Utilizando esta universidad como categoría de comparación, las universidades estadísticamente más machistas fueron una privada de Chiclayo (α=3,63; p<0,001), seguida de una particular en Huancayo (α=3,20; p=0,001), la nacional de Huancayo (α=2,79; p<0,001) y la pública de Ica (α=2,32; p=0,006); los cruces se ajustaron por la edad.

ConclusionesSe encontró que el machismo es mayor entre los no creyentes, los varones y en algunas universidades, con predominio de universidades de la sierra central del Perú o con migrantes de la serranía. Esto es importante, ya que brinda un panorama acerca de este rasgo de los que serán los futuros encargados de velar por la salud de los peruanos.

Sexism has always been present throughout history, manifesting itself with derogatory attitudes towards the rights and roles of certain groups, in particular to the detriment of women, who have been ignored in certain aspects and periods of history.1

In Latin America, male chauvinism is considered a form of sexism,2 which refers to beliefs and expectations with regard to the role of men in society3 and can adopt extreme attitudes such as femicide,4 the incidence of which has increased in recent years, in particular in rural areas.5 These types of male chauvinist attitudes have also been reported among university students. A study conducted at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [National Autonomous University of Mexico] reported that 100% of women surveyed claimed that there was gender discrimination in their university.6

Various factors which have an influence on, and intensify male chauvinism have been found; some of them are religious movements which tend to silence, discriminate against and make women “invisible”.7,8 As an example of this, a high rate of male chauvinism has been reported among pupils of parish schools,9 as well as a strong association between religious commitment and negative attitudes towards homosexual males.10

Although studies have been published in countries similar to Peru, which show that being a woman, having a homosexual orientation and holding certain religious beliefs are factors directly associated with male chauvinism,11,12 this topic has not been studied among Peruvian medical students. It is important to determine the factors which predispose to this attitude, as in the future the doctor-patient relationship may be affected. The objective of this study was therefore to determine the factors associated with male chauvinism among medical students at 12 Peruvian universities.

MethodsStudy designAn analytical, observational, cross-sectional study was carried out. A secondary analysis of the database collected by a primary investigation (which investigated homophobia among medical students) was used.

Study populationThe study population was made up of students from the medical schools of 12 Peruvian universities. The responses of students on the medical degree who were enrolled in the semester 2016-I, in the 1st to 6th years of study and who agreed to voluntarily take part in the study were included. Students from other degrees and also those who did not respond to the main questions of the male chauvinism test were excluded (exclusion<5%).

Sample and samplingProbability sampling was performed, with a sample size found by comparing two means (44.94 and 38.42) obtained from a study conducted on medical students. An error rate of 5% and a statistical power of 99% was worked with. A sample size of 198 students was obtained for each school in the study.

Male chauvinism variableThe main variable was “being a male chauvinist”, which was obtained according to the sexual male chauvinist scale created by Díaz Rodríguez et al., which uses vocabulary that can be understood by the entire Latin American population, in addition to referring to a factor which explains 98% of the variance in the confirmatory factor analysis and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.91. The test consisted of 12 questions, with a maximum of 60 points and a minimum of 12 points, with the highest number indicating a tendency towards male chauvinism. Answers were given using a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (from strongly agree to strongly disagree).13 To generate the analytical part, the upper tertile (which indicates a higher degree of male chauvinism and was taken as an indicator of male chauvinism) was compared with the sum of the two lower tertiles.

Religiousness and other variablesThe degree of religiousness was measured with the short version of the Francis scale. This scale has a single-dimension structure and a variable which explains 74% of the variance; the data show their reliability and correct values of internal consistency. The test used had five questions which aimed to measure certain actions in light of religious divinities (such as God or Jesus).14 The Francis scale also uses Likert scale responses, similar to those already explained. The sum of the responses was also categorised here and the category of interest was that which showed the least religiousness (compared to higher values+the intermediate values).

The university variable was categorised into: Universidad San Martín de Porres [San Martín de Porres University] (USMP) (with its two campuses: Lima and Chiclayo), Universidad Nacional Pedro Ruiz Gallo [Pedro Ruiz Gallo National University] (UNPRG) in Chiclayo, Universidad Nacional de Piura [Piura National University] (UNP) in Piura, Universidad Nacional San Luis Gonzaga [San Luis Gonzaga National University] (UNSLG) in Ica, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia [Cayetano Heredia Peruvian University] (UPCH) in Lima, Universidad Ricardo Palma [Ricardo Palma University] (URP) in Lima, Universidad Nacional José Faustino Sánchez Carrión [José Faustino Sánchez Carrión National University] (UNJFSC) in Huacho, Universidad Nacional San Cristóbal de Huamanga [San Cristóbal de Huamanga National University] (UNSCH) in Ayacucho, Universidad Nacional del Centro del Perú [National University of Central Peru] (UNCP) in Huancayo, Universidad Nacional de Hermilio Valdizán [Hermilio Valdizán National University] (UNHEVAL) in Huánuco and Universidad Peruana Los Andes [Los Andes Peruvian University] (UPLA) in Huancayo.

Other variables analysed were gender and age (in years).

ProceduresThe list of students from 1st to 6th year from the 12 medical schools was compiled. The participants were selected by means of random sampling and it was proceeded with the collection of data from an online survey carried out on the platform Google Docs®.

For contact with the participants, the authors communicated with each one of those selected on the phone and online (email and Facebook®). The data were collected between July and December 2016.

Data analysisThe data were tabulated in Microsoft Excel (version 2013 for Windows). Subsequently, the variables chosen were imported from the primary base to the statistical software Stata version 11.1 (StataCorp LP; College Station, Texas, United States), through which the different statistical analyses were performed.

First, a descriptive analysis of the categorical variables was carried out, to show the frequency and the percentage of each response, despite knowing that these responses separately have less weight than the overall score, as it will provide a general idea of the perception of each item.

In the bivariate and multivariate analysis, generalised linear models were used, using the Poisson family, the log link function and robust models, and prevalence ratios (PR), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and p-values were obtained. A p-value<0.05 was considered as the limit of statistical significance.

Ethical considerationsAs it was a secondary database study, it was not submitted for review by an ethics committee; however, the primary project did have this approval. The database analysed did not include variables which could identify the participants. Furthermore, the international parameters for the processing of scientific information were followed.

ResultsOf the 902 medical students surveyed, 51.8% (468) were females and 13% (118) of the total number of respondents were studying at the national university in Huacho, located in the coastal region of the country. In addition, it was found that 29.5% (262) of the students are male chauvinists and 47.2% (340) are non-believers.

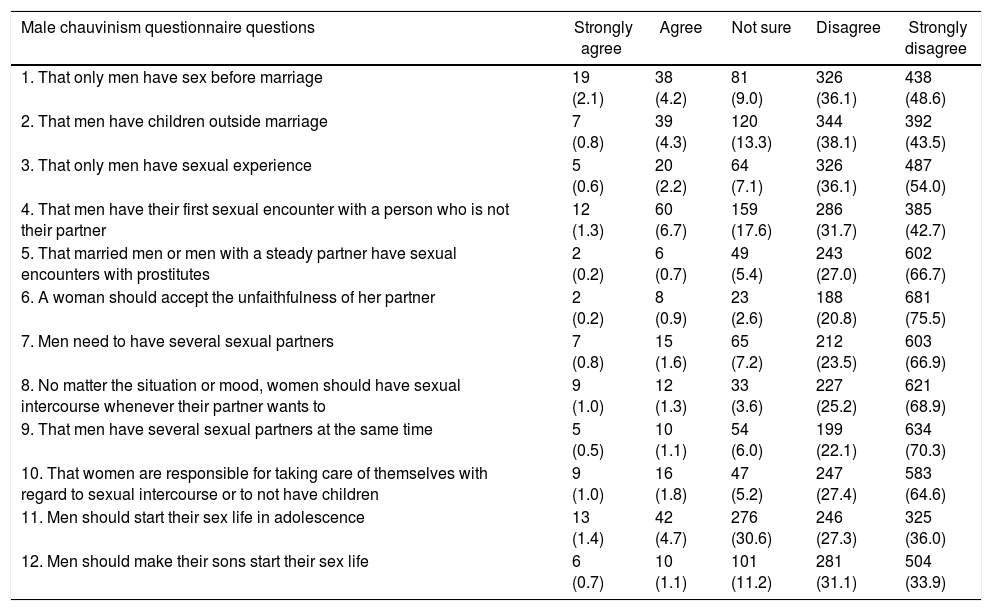

A total of 1.3% and 6.7% of the students, respectively, strongly agree or agree with the statement “that men have their first sexual encounter with a person who is not their partner”. A total of 2.1% and 4.2% strongly agree or agree with the statement that “only men have sex before marriage” and 1.4% and 4.7% strongly agree or agree that “men should start their sex life in adolescence” (Table 1).

Frequency of responses to the questionnaire on male chauvinism among medical students at Peruvian universities.

| Male chauvinism questionnaire questions | Strongly agree | Agree | Not sure | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. That only men have sex before marriage | 19 (2.1) | 38 (4.2) | 81 (9.0) | 326 (36.1) | 438 (48.6) |

| 2. That men have children outside marriage | 7 (0.8) | 39 (4.3) | 120 (13.3) | 344 (38.1) | 392 (43.5) |

| 3. That only men have sexual experience | 5 (0.6) | 20 (2.2) | 64 (7.1) | 326 (36.1) | 487 (54.0) |

| 4. That men have their first sexual encounter with a person who is not their partner | 12 (1.3) | 60 (6.7) | 159 (17.6) | 286 (31.7) | 385 (42.7) |

| 5. That married men or men with a steady partner have sexual encounters with prostitutes | 2 (0.2) | 6 (0.7) | 49 (5.4) | 243 (27.0) | 602 (66.7) |

| 6. A woman should accept the unfaithfulness of her partner | 2 (0.2) | 8 (0.9) | 23 (2.6) | 188 (20.8) | 681 (75.5) |

| 7. Men need to have several sexual partners | 7 (0.8) | 15 (1.6) | 65 (7.2) | 212 (23.5) | 603 (66.9) |

| 8. No matter the situation or mood, women should have sexual intercourse whenever their partner wants to | 9 (1.0) | 12 (1.3) | 33 (3.6) | 227 (25.2) | 621 (68.9) |

| 9. That men have several sexual partners at the same time | 5 (0.5) | 10 (1.1) | 54 (6.0) | 199 (22.1) | 634 (70.3) |

| 10. That women are responsible for taking care of themselves with regard to sexual intercourse or to not have children | 9 (1.0) | 16 (1.8) | 47 (5.2) | 247 (27.4) | 583 (64.6) |

| 11. Men should start their sex life in adolescence | 13 (1.4) | 42 (4.7) | 276 (30.6) | 246 (27.3) | 325 (36.0) |

| 12. Men should make their sons start their sex life | 6 (0.7) | 10 (1.1) | 101 (11.2) | 281 (31.1) | 504 (33.9) |

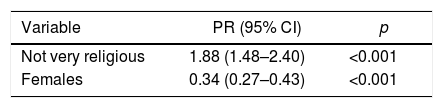

In the bivariate analysis of the questions on religiousness and sex, being a male chauvinist had a direct relationship with being a non-believer (PR=1.88; 95% CI, 1.48–2.40), while being a woman was associated negatively with male chauvinism (PR=0.34; 95% CI, 0.27–0.43) (Table 2).

Bivariate analysis of male chauvinism according to religiousness and the gender of medical students at Peruvian universities.

| Variable | PR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Not very religious | 1.88 (1.48–2.40) | <0.001 |

| Females | 0.34 (0.27–0.43) | <0.001 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; PR: prevalence ratio.

p-Values obtained with generalised linear models, with Poisson family, log link function and robust models.

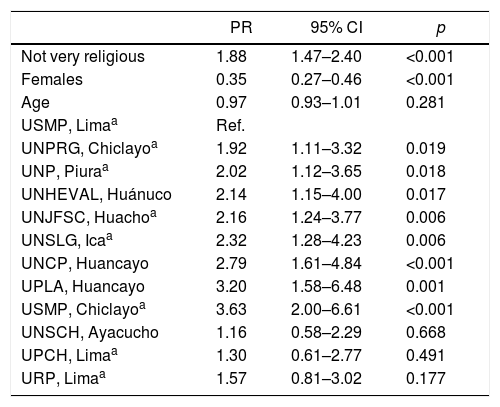

In the multivariate analysis an association was found between being a male chauvinist and not being very religious (PR=1.88; 95% CI, 1.47–2.40), as well as being a woman (PR=0.35; 95% CI, 0.27–0.46). Of the 12 universities evaluated, the least male chauvinistic was the USMP in Lima. Using this university as a comparison category, the most male chauvinistic universities from a statistical perspective were a private university in Chiclayo (α=3.63; p<0.001), followed by another private university in Huancayo (α=3.20; p=0.001), the national university in Huancayo (α=2.79; p<0.001) and the public university in Ica (α=2.32; p=0.006). For all these crosstabs, an adjustment was made for age (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis of male chauvinism according to socio-educational variables of medical students at Peruvian universities.

| PR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not very religious | 1.88 | 1.47–2.40 | <0.001 |

| Females | 0.35 | 0.27–0.46 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.97 | 0.93–1.01 | 0.281 |

| USMP, Limaa | Ref. | ||

| UNPRG, Chiclayoa | 1.92 | 1.11–3.32 | 0.019 |

| UNP, Piuraa | 2.02 | 1.12–3.65 | 0.018 |

| UNHEVAL, Huánuco | 2.14 | 1.15–4.00 | 0.017 |

| UNJFSC, Huachoa | 2.16 | 1.24–3.77 | 0.006 |

| UNSLG, Icaa | 2.32 | 1.28–4.23 | 0.006 |

| UNCP, Huancayo | 2.79 | 1.61–4.84 | <0.001 |

| UPLA, Huancayo | 3.20 | 1.58–6.48 | 0.001 |

| USMP, Chiclayoa | 3.63 | 2.00–6.61 | <0.001 |

| UNSCH, Ayacucho | 1.16 | 0.58–2.29 | 0.668 |

| UPCH, Limaa | 1.30 | 0.61–2.77 | 0.491 |

| URP, Limaa | 1.57 | 0.81–3.02 | 0.177 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; PR: prevalence ratio.

Male chauvinism among medical students was approximately 30%. The statement that scored highest on the male chauvinism scale was that men have their first sexual encounter with a person who is not their partner. This is consistent with the results of a sociological analysis carried out in Spain, which found that at least 22% of males have had sexual intercourse with someone who is not their partner.15 It is also consistent with an investigation carried out in Colombia, which confirms that the majority of adolescents start their sexual life motivated by “social pressure of masculinity”.16 This could be explained by the concept that society has of men, that it considers a man like an “animal” to which certain actions can be justified due to their “nature”, an ingrained perception both in males and in females of many societies. These types of attitude promote the development and establishment of male chauvinist ideas, both in Latin America and in the East, where male chauvinist attitudes are even normalised.17–19 This leads to the myths on male sexuality being questioned, which drive the strengthening of a male chauvinist culture20 that could be associated with existing sexual violence. This even creates a feeling of guilt in victims, which occurs due to the inadequate justification of certain acts seen as normal by the male chauvinist society.21

The association between not being very religious and male chauvinism differs from that reported in a study in El Salvador, which found a positive association between religion and male chauvinism,22 and in another study of triple association between religion, homophobia and male chauvinism, which concluded that there is a percentage of believers who are male chauvinists and who generate different forms of discrimination, notably homophobia,23,24 despite it being proven that homosexual people have a greater degree of awareness regarding gender discrimination.25 It is important to highlight the above given that our study removes religion to a certain extent as a main predisposing factor to male chauvinism, as has been reported frequently in different studies, and suggests that there are other more influential factors in male chauvinist behaviour. This must be studied so that it can be determined if there are special groups (as it is known that there is much segmentation between people who practise religion) or other factors which could be influencing this relationship.

The total figure of male chauvinism is still lower than that found in a study in Chilean universities,19 possibly due to a difference in measuring scales, although it may also be due to the fact that the objective of the Chilean study was to describe the frequency of male chauvinism, which was not the objective of our study. In England, one study found higher figures, peaking at 46% for any type of gender violence. However, it is important to point out that this study focuses on the student population of approximately 16 and 19 year-olds,21 which could explain the differences with our study. However, there are no specific studies on male chauvinism in medical students in any of these countries mentioned, which is necessary and useful in order to take a brief look at the male chauvinism that is being experienced at the moment, even in the healthcare setting, and to observe how this can affect the type of healthcare in the community. It is recommended that future research be carried out which tries to find the prevalences of male chauvinism among students. Such research should incorporate the use of sampling techniques that make it possible to extrapolate to these populations.

Male chauvinism of students could come from their training at home, which is known to be characterised by the marked role of superiority of the male figure.26 In this context, it is important to emphasise the cultural environment where they live, as this has a significant impact on the possible stereotypes and the establishment of male chauvinist behaviour.27 Despite the fact that our study found a percentage of male chauvinism<50% in the vast majority of universities evaluated, it is essential to carry out strategies to resolve this problem, especially given the future implications that it may have on their medical activity,28 as has been demonstrated at Yale University, where it has been proven that women face difficulties being recognised in their field of research.29 Universities need to perform psychological and personality tests, where they can establish these and other traits and identify cases eligible for psychological support therapies.

The USMP in Chiclayo, the UPLA in Huancayo, the UNCP in Huancayo and the UNSLG in Ica are the universities which present the highest percentage of male chauvinism. Of these, the second and third are in the country's mountain region. There are also reports that the USMP in Chiclayo and the UNSLG in Ica have significant percentages of students from the mountainous areas of Cajamarca and Ayacucho, respectively, which is why it could be hypothesised that students who are originally from the mountain areas are more likely to be male chauvinists. These figures are consistent with other research carried out in other countries30 and in cities in the Central Highlands of Peru, such as a study conducted in the city of Cerro de Pasco, which revealed that 32% of males exhibit a high rate of male chauvinism.31 One of the possible explanations for this is the conservative setting that has been recorded in this region, in addition to the well-defined sexist roles that lead to gender violence. One case to highlight is that of the USMP, as its campus in Lima obtained the lowest percentage of male chauvinism, in contrast to its campus in the province (and this occurred despite the fact that they are both in the coastal region), which shows that social and/or behavioural variables could be influencing the results. This reinforces the hypothesis that there is greater migration among students from the mountainous departments close to Chiclayo who, for study purposes, move to the coast, maintaining their customs due to their strong identification with the culture of their home town.32 Furthermore, the process of psychological acculturation that the population of Chiclayo may suffer from, which consists of the different psychosocial changes that occur in a population due to contact with people from a different culture, should be taken into account.33 In view of all of the above, it is necessary to take into account the regional differences between the coast and Peruvian mountainous areas, with noteworthy gender stereotypes which are more prominent in the mountainous areas than on the Peruvian coast.16,34 Our study shows that the mountainous areas have higher rates of male chauvinism and gender violence than the Peruvian coastal areas. Despite this, levels of gender violence are actually higher on the coast. This could be explained by the current demographics, which show that there are up to 56% more inhabitants living on the coast.

Among the strengths of our study is the fact that it is multi-centre; information was gathered from a large number of departments on the coast and in the mountainous areas of Peru, in addition to having a considerable population aged between 20 and 23 years, which provides a greater level of confidence in the responses. The main limitation of the study is that the results cannot be extrapolated to each one of the campuses as there was not a randomisation process for each university. Therefore, a specific university and/or religious group cannot be categorised. Hence it cannot be claimed categorically that not being very religious or studying at a certain university are predisposing factors to male chauvinism, but the results can be used as preliminary results due to the large population sample and the diversity of the campuses included.

In view of everything mentioned in the population evaluated, it can be concluded that male chauvinism is more prevalent in males, among those who are not very religious and in certain university campuses evaluated, with predominance of high frequencies among some educational establishments located in the Peruvian Central Highlands area or with an influence of migration from cities in the mountainous area. Expanding the population and taking into account students from the Peruvian forest region is recommended for future research.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interestThe student authors are studying at the educational establishments evaluated, but this did not have any impact on the results or any another section of the article.

Please cite this article as: Mejia CR, Pulido-Flores J, Quiñones-Laveriano DM, Nieto-Gutierrez W, Heredia P. Machismo entre los estudiantes de medicina peruanos: Factores socio-educativos relacionados en 12 universidades peruanas. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2019;48:215–221.