We describe seven cases of patients with an inability to cry after treatment with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI) medication, even during sad or distressing situations that would have normally initiated a crying episode, in the light of the role of the serotonergic system in emotional expression.

MethodCase series drawn from patients attended in a secondary care psychiatry service.

ResultsWhile excessive crying without emotional distress has been previously reported in the literature, and is associated with reduced serotonin function, these reports suggest cases of the reverse dissociation, where emotional distress and an urge to cry was present, but crying was impaired.

DiscussionAlthough the case series presented here is new, these cases are consistent with the neuroscience of crying and their relationship with serotonergic function, and provide preliminary evidence for a double dissociation between subjective emotional experience and the behavioural expression of crying. This helps to further illuminate the neuroscience of emotional expression and suggests the possibility that the phenomenon is an under-recognised adverse effect of SSRI treatment.

Se describen los casos de 7 pacientes con incapacidad para llorar tras tratamiento con un inhibidor de la recaptación de serotonina (ISRS), situación que se presenta aun en situaciones estresantes o tristes, que normalmente les habrían iniciado una respuesta de llanto. Los casos se examinan a la luz de lo que se conoce acerca del papel del sistema serotoninérgico en la expresión emocional.

MétodoSerie de casos de pacientes que acuden a un servicio de atención secundaria en psiquiatría.

ResultadosMientras el llanto excesivo sin estrés emocional ya se había descrito en la literatura asociado con una función serotoninérgica reducida, los presentes reportes apuntan casos de la disociación inversa, en los que el estrés emocional y la urgencia de llorar se encontraban presentes, pero con incapacidad para el llanto.

DiscusiónAunque la serie de casos aquí presentada es nueva, concuerdan con la neurociencia del llanto y su relación con la función serotoninérgica, y proveen evidencia preliminar para una disociación doble entre la experiencia emocional subjetiva y la expresión conductual del llanto. Esto ayuda a elucidar la neurociencia de la expresión emocional y apunta la posibilidad de que el fenómeno sea un efecto adverso poco detectado del tratamiento con ISRS.

“Cuando quiero llorar, no lloro, y a veces lloro sin querer…” (Canción de Otoño en Primavera, Rubén Darío)

Dysfunctions in emotional modulation, experience, and ex pres sion are frequent in patients with both primary and secon dary psychiatric disorders. Uncontrollable or involuntary crying has been widely reported after many types of neurological damage or disease, where it may be labelled as ‘pathological laughing or crying’, ‘pseudobulbar affect’, ‘emotionalism’ or ‘involuntary emotional expression disorder’ (IEED) to name but a few of the many terms in use.1 Conversely, while crying is most typically associated with mood disorders, evidence that depression leads to more frequent crying, or, conversely, that severely depressed individuals lose their capacity to cry, is mixed, and little reliable empirical evidence for the connection between mood pathology and crying can be found in the literature.2 However, it is clear from the clinical literature that crying behaviour and emotional distress can dissociate, so people who experience involuntary crying may not necessarily experience the subjec tive emotional feeling that usually accompanies these episodes.3,4 This paper reports on 7 cases that demonstrate the reverse dissociation, an inability to cry after intervention with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medication, despite the subjective emotional feeling of sadness and the urge to cry, indicating a perhaps under-recognised adverse effect and providing further evidence for the neural basis of crying regulation.

Previous studies on the possible neurological basis of pathological crying have not come to any clear conclusions as to which neural circuits are implicated in the condition and, to complicate matters for those specifically interested in crying, it is often the case that excessive crying and excessive laughing are studied as the same phenomenon. The first and still influential theory of pathological laughing and crying suggests that it results from ‘disinhibition’ or ‘release phenomenon’ after damage to the voluntary inhibitory mechanisms in the upper brain stem.5 However, it has become increasingly clear that excessive crying is not obviously linked to damage to any one specific brain area.6 Indeed, prior reports based on lesion data have implicated a wide range of specific cortical and subcortical areas, with recent theories focusing on two major pathways: the cerebro-ponto-cerebellar pathway7 and the cortico-limbic-subcortico-thalamic-ponto-cerebellar network.8 In a recent review of the literature, however, Nieuwenhuis-Mark et al1 noted that the most commonly implicated areas from the lesion data include the limbic system, brain stem and frontal lobes, as well as evidence for excessive crying being linked to a greater level of overall damage and a lower ratio of serotonin transporter (SERT) binding ratios in the brain stem.

The link with serotonin transporter has emerged from two neuroimaging studies that have used radioligand binding to understand serotonin function in stroke patients with pathological crying. A single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) study by Murai9 found lower SERT binding ratios in the midbrain and pons in pathological crying patients compared to non-affected controls, while a positron emission tomography (PET) study by Møller, Andersen et al10 found a globally lower level of 5HT1A receptor binding associated with pathological crying. This is in line with evidence that serotonergic medication is an effective treatment for excessive crying,11 and that it typically resolves crying episodes at lower doses than are needed to treat depression. Furthermore, resolution of excessive crying typically occurs within days, in contrast to the several weeks typically needed for the mood elevating effects.12–14 In line with this, excessive crying is recognized as a symptom of SSRI discontinuation syndrome.15

From this evidence, a clear prediction emerges that the over-modulation of serotonergic pathways would induce the inability to cry in some patients. However, this is a topic that has rarely been addressed in the clinical literature. In fact, to our knowledge, only two minor reports exist. In a letter to the editor, Oleshansky et al16 discussed 3 patients who seemingly ‘lost’ their ability to cry after starting treatment with SSRI medication with examples of specific episodes that typically caused crying in the past but no longer triggered a tearful response. In addition, a short report by Opbroek et al.17 described 15 patients with sexual dysfunction after SSRI treatment, of which 60% (n=9), reported that they experienced the ability to cry ‘a lot less than usual’. However, no con textual details were given, so it is difficult to say to what extent this effect may have been due to changes in exposure to emotional stimuli, changes in appraisal of emotional events, or a loss of ability to control tears, all three of which are cited as possible processes having an effect on crying frequency.1

In the present study we report a series of 7 psychiatric patients without neurological damage who presented with an inability to cry during treatment with SSRIs, even during extremely sad or moving situations that were cited as likely to have previously initiated a crying episode. We discuss implications for serotonergic models of emotional control and the understanding of how subjective emotional feeling and emotional expression may dissociate.

Case ReportsCase 1A female patient aged 43, presented to psychiatric consultation due to a depressive episode, with profound sadness and anhedonia, sleep disturbance, low energy, negative cognitions, and difficulties in concentration. On the first consultation, she scored 27 on the Beck Depression Inventory version 1A (BDI). A neurological examination and recent CT scan reported no abnormalities and she had no history of neurological disease or acquired brain injury. A general physical examination found no abnormalities and blood, glucose, thyroid, hepatic function and creatinine tests were all in the normal range. The patient was started on escitalopram 10mg/day. After five weeks of treatment she reported feeling quite well and her score on the BDI reduced to 8, within the ‘no depression’ range. After 2 months of treatment, she felt she was no longer depressed and considered that her day-to-day functioning, relationships and quality of life had returned to normal. However, she mentioned she had noticed something that seemed very curious to her — her pet dog had died one week ago and although she felt very sad and wanted to cry, she was unable. She reported the experience as puzzling: “I felt a bit strange, you know… I really wanted to cry, and I was feeling like if I was on the brink of doing it, but it is like if my face and my eyes could not do it”. She was emphatic in saying that she was not apathetic, that her capacity for enjoying life was preserved, that it was something only affecting her capacity for crying. She did not want to stop the medication, fearing a relapse. The patient has continued taking the medication, and the inability to cry has persisted. She considered this as a curious but tolerable side-effect, although she wondered if being unable to cry would have later consequences because of “repressed sad feelings”, considering crying as cathartic and that being unable to cry might “not be good for your mental health”.

Case 2A 23 year-old male patient presented to psychiatric consultation with a history of obsessive compulsive disorder commencing around the age of 15. His obsessions included intrusive thoughts concerning obscenities and contamination. His compulsions were restricted to washing rituals. He did not tolerate sertraline, because of nausea and sleepiness, and he was subsequently started on fluvoxamine which was increased to 300mg/day and was tolerated well. After 8 weeks of taking fluvoxamine, severity, frequency and interference of both obsessions and compulsions were greatly diminished. He reported no comorbid depression, but fulfilled criteria for generalised anxiety disorder, although he reported that he felt his tendency for excessive worry had improved with treatment. After four months of treatment he noticed that he was unable to cry. Two weeks before the consultation he ended his romantic relationship and felt sad, wanting to cry, but could not, as if his “capacity for crying was frozen”. He was neither apathetic, nor depressed (BDI score 7). After discussing the matter with him, he preferred not to change fluvoxamine treatment, because, apart from the inability to cry, he was very satisfied with the results of the treatment and considered this side effect a minor inconvenience.

Case 3A 30 year-old male patient presented to consultation because of a depressive episode that started at least 5 months previously, with a score of 25 on the BDI. This was his third major depressive episode. A CT scan, neurological examination, thyroid levels, and other general laboratory exams were normal. The patient had a history of good response and remission with sertraline 100mg/day in all previous episodes and was subsequently restarted on this treatment regime. After 8 weeks of treatment, his depression was in remission, scoring 5 (‘no depression’) on the BDI. However, he noticed that he was unable to cry, even when feeling sad. He described the situation where his mother was diagnosed with a severe coronary disease, and, although he felt very sad and wanted to cry, he couldn’t because “it was as if I had no tears, as if my face didn’t remember how to cry”. He remembered having the same experience during previous treatments, but he did not feel the need to mention it. Subsequent to this point, the patient has been on the treatment for 12 months, and the inabi lity to cry has diminished, although he says that it is still present to a certain degree. He considers that crying could be healthy on some occasions, but that usually he was not a “very tearful person” and that he only tended to cry and being excessively moved by events when depressed or with severe stressors.

Case 4A 45 year-old female patient presented to consultation with her fourth depressive episode. She had previously been prescribed buproprion and venlafaxine but these treatments were abandoned because of side-effects (mainly headache, constipation, irritability and dizziness). She also had previous treatment with f luoxetine 20mg/day that she tolerated better, although with diminished libido. After discussing alternatives, the patient was prescribed citalopram 20mg/day. A CT scan, neurological examination, thyrioid test and other medical examinations were normal. The initial BDI score was 23. After 4 weeks, she reported feeling much better and quite comfortable with the citalopram (BDI score 13). However, after week 12 she complained of diminished sexual desire and a delay in reaching orgasm. Although in her opinion, the side-effect was less than with fluoxetine, she was motivated to request a consultation to discuss alternatives. During the meeting she remarked “a quite surprising inability to cry”. She noticed that when watching very moving films (an event that almost always led her to cry) she “simply couldn’t cry”. She reported no apathy, depression, anhedonia or other mood manifestations (BDI score 9). She found that the experience of not being able to cry was surprising, but not really distressing. Buspirone, up to 40mg/day for 6 weeks, was added to her treatment regime in an attempt to address the sexual side-effects. Sexual function improved although not to levels previous to treatment. She also noticed that her ability to cry had improved (e.g., she would shed tears in a very moving movie, she cried during a memorial service and found that in both occasions “it felt right and relieving to cry”). She remains on both treatments and feels satisfied with them.

Case 5A 60 year-old woman presented to consultation with a seventh major depressive episode and a history of previous treatments with sertraline and escitalopram. CT scan was reported as normal for her age, with no evidence of vascular disease or atrophy or other findings that would make think about a neurological disease. Although she had a history of hypothyroidism, she was on treatment and a recent thyroid work-up was within normal range. She was subsequently prescribed escitalopram 10mg/day and, after 7 weeks of treatment, she reported significant improvement. However, she noted that she was unable to cry when going to the cemetery to visit her husband's grave or when one of her grand children had an accident. She felt that “I was very sad but I was like dry inside. I wanted to cry, but couldn’t shed a single tear”. After 10 weeks, her depression was markedly improved although her inability to cry continued. She is still on the same treatment and the inability to cry continues without change although the patient does not feel this side-effect warrants a change of treatment. She was not concerned by the inability to cry in itself, but she considered that the fact she was not able to shed tears when visiting her late husband's tomb “was not right”.

Case 6A 35 year-old male patient reported to consultation with a third depressive episode. A neurological examination found no abnormalities, and other medical tests (blood, thyroid, HIV, blood sugar, etc.) were normal. The patient had no prior history of previous pharmacological treatment. He was started on escitalopram 10mg/day and reported that his depression had significantly improved after 4 weeks. However, he complained about a significant decrease in sexual desire and delayed ejaculation. He also noticed that, paradoxically, when feeling sad, he was unable to cry. For example, he remembered that he saw reports of hostages being released he felt very moved, saying “emotionally I was crying, but in my face no change happened”. Similarly during a very difficult argument with his boyfriend he remembered that “I wanted to cry, I feel like crying, but my body doesn’t respond, like if my crying apparatus is broken”. He wanted to wait longer before thinking about changing his medication hoping that the sexual side effects would subside. He experienced the inability to cry as something curious, but not especially distressing. However, he wanted to be able to cry in appropriate situations, for example, during a memorial service, because it seemed to him that not being able to cry in some circumstances might not be polite or healthy. Several weeks later, he went on a three day trip, and forgot to take his medication. Besides the usual discomfort due to sudden SSRI discontinuation, he had several “crying spells”. He described these spells as “crying without reason, like veritable storm of tears”. He was emphatic in denying any sad mood accompanying the crying spells. After a further consultation, the patients started mirtazapine, that was not well tolerated due to excessive sleepiness. Subsequently, he was prescribed brupropion, and had a noticeable increase in anxiety and irritability. Finally, he was started on reboxetine, that effectively treated his depression without sexual dysfunction. He has reported no further episodes of an inability to cry.

Case 7A 34 year-old female patient reported to consultation owing to an onset of a major depressive episode. The patient had a prior diagnosis of dysthymia and double depression (a concept used more widely in the Americas, that describes an acute episode of major depressive disorder superimposed on dysthymia18), and had a history of good symptomatic response to paroxetine. She was therefore restarted on paroxetine 20mg, but after 5 weeks the response was still partial and therefore the dosage was increased. Three weeks later she reported having continued improvement and after 12 weeks she was reported feeling significantly improved and did no longer qualified for a diagnosis of major depression. However she complained of low sexual desire and delay in orgasm. She also noticed that “When I want to cry, I can’t. It's like my body had forgotten how to cry. I try, but I can’t.” For example, one of her neighbours died, an event that usually would have led her to cry, but he was not able to do so. She noticed a similar inability after arguments with her partner or mother. She was concerned whether being unable to cry was normal or whether it would have negative consequences. However, she preferred to continue paroxetine treatment, because of the improvement of her mood symptoms. In order to improve sexual response, burproprion 150mg/day was added. After several weeks, sexual desire and response improved. However, her inability to cry has continued.

DiscussionWe have reported 7 cases in which patients treated with a diverse range of SSRIs presented with an inability to cry after several weeks of treatment, even when distressed and in situation which would normally lead to crying. This was recounted by patients as if the bodily systems involved in crying were “frozen”, had “broken” or that the “body had forgotten how to cry”, in which the patients demonstrated a dissociation between the presence of subjective feelings of distress and an urge to cry; and the expressive, motor components of affect. It is important to emphasise that the patients were neither apathetic nor blunted in their feelings — i.e. their subjective experience of emotion was preserved.

Significantly, several of the patients reports that this inability manifested itself in situations where they would normally have cried on previous, pre-treatment, occasions; that they appraised the situation as emotionally distressing; and that they experienced an urge to cry. Nieuwenhuis-Mark et al1 have criticised some earlier studies of crying, noting that they often do not specifically address differences in exposure to emotional stimuli, changes in appraisal of emotional events, or the control of the urge and expression of tears, and it is notable that, unlike the present study, neither of the previous two reports of reduced crying after SSRI treatment16,17 allow these factors to be fully accounted for.

These case studies provide further evidence of the importance of serotonergic systems in the control of crying. While all SSRI medication is thought to derive its clinical effect from the high affinity for the serotonin transporter and the in creases in the eff iciency of post-synaptic 5HT transmission,19 the secondary effects of individual compounds are remarkably variable. Indeed, compounds associated with inability to cry in the present study have a range of secondary effects: fluvoxamine on sigma-1 receptors, paroxetine on muscarinic receptors, sertraline on dopamine receptors, and citalopram and escitalopram on histamine receptors (review in Carrasco et al20). The fact that in the present study an inability to cry was associated with a range of SSRIs with differing secondary effects suggests that it is the primary action on increasing synaptic availability of serotonin which mediates the effect. This is in line with clinical evidence that SSRIs can treat pathological crying,11 that SSRI discontinuation can lead to crying spells15, and the radioligand neuroimaging evidence of lower serotonin turnover in subcortical areas associated with pathological crying after stroke.9,10

It is notable that all patients reported here described a dissociation between crying and subjective feelings of sadness. Indeed, this dissociation has been reported previously, although typically in its opposite form, where pathological crying is present without the subjective emotional component. This has been reported in cases of acquired brain injury, stroke, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease (see review in Wortzel et al21), as well as a side-effect of deep brain stimulation to the caudal internal capsule22, and the subthalamic nucleus.3,23 While this dissociation is most commonly reported after neurological disorder, as the phenomena of experienced emotion without the normal behavioural expression is known in schizophrenia, where diminished facial expression of emotion can be accompanied by a full subjective emotional experience.24

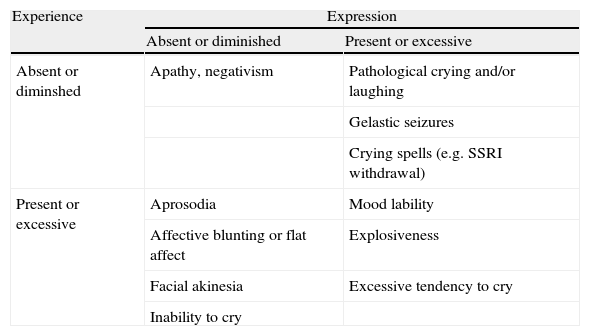

From a psychopathological point of view, an understanding of how expression and subjective emotion may dissociate is still in a very preliminary state with a more refined conceptualisation still lacking. With this in mind, we offer a tentative classification of how syndromes could be categorised by the distinction of emotional expression and emotional experience (table 1).

Examples of affective symptoms classified as disorders of emotional experience and expression

| Experience | Expression | |

| Absent or diminished | Present or excessive | |

| Absent or diminshed | Apathy, negativism | Pathological crying and/or laughing |

| Gelastic seizures | ||

| Crying spells (e.g. SSRI withdrawal) | ||

| Present or excessive | Aprosodia | Mood lability |

| Affective blunting or flat affect | Explosiveness | |

| Facial akinesia | Excessive tendency to cry | |

| Inability to cry | ||

At present, the justification for our classification is largely based on clinical observation: patients complain of excesses or deficits in the experience of some emotions and/or their expression. On the basis of the value of dissociation in cognitive neuropsychiatry research25, this plausible although tentative descriptive classification suggests that there may be distinct mechanisms underlying subjective experience and emotional expression (importantly, beyond the simple control of the musculature), although exactly how distinct and how separable in terms of cognitive and neural subsystems remains to be seen. For example, we would expect at the least a significant two-way feedback between the experience and expression components considering evidence that voluntarily forming expressions can have a reciprocal effect on mood (e.g. Kleinke et al26).

It is also notable that the patients reported here did not report apathy or emotional blunting, suggesting that inability to cry was dissociated from both. This is important as each can evidently present as symptoms of major depression, and moreover, each has been reported as a result of SSRI treatment.27 In this case series, however, an inability to cry was associated with other ‘inhibitory’ side-effects: in cases 4, 6 and 7, sexual dysfunction was apparent and, interestingly, intervention to counteract or compensate for this well-known serotoninergic side-effect also reversed the inability to cry. In patient 6, the reversal of inability to cry can be considered extreme, because of the subsequent presentation of crying spells on unplanned withdrawal of citalopram. Although there is no research that addresses this directly, we wonder whether these ‘inhibitory’ effects may be on a continuum, where greater serotonergic modulation has an increasingly inhibitory effect on some function or patients to the point of apathy at the most extreme end of the spectrum.

With regards to the possible clinical effects of an inability to cry, it is notable that the experience was reported as noteworthy enough to mention to a doctor but not particularly distressing in itself. The reporting of this experience in a clinical context remind us of the social and cultural components of emotional expression that form part of the attribution that something seems out of the ordinary or emotionally ‘wrong’ and it is notable that several of the patients mentioned that they were concerned about the consequences for their mental health, reflecting the widespread view that crying is cathartic.28 However, empirical support for the catharsis hypothesis is mixed and the cathartic effect of crying has been found to be modulated by the response of others, as much as any intrinsic value to crying itself.29 Perhaps most relevantly, a recent study, albeit solely on women,30 found that while the majority (89%) reported relief from crying, those with symptoms of depression, anxiety, anhedonia and/or alexithymia reported that crying left them feeling worse or just the same. However, in this case series, the majority of patients had recovered from their index diagnosis while being unable to cry, and it is not clear from this evidence whether this inability prevents them from accessing a useful form of emotional release, protects them from unhelpful crying spells (particularly considering the psychological and neurobiological vulnerability factors still present in recovered depressed patients31,32), or has no effect either way.

ConclusionsWe report a dissociation between intact subjective emotional distress and impaired ability to cry related to the use of SSRI medication. Although the study has limitations inherent to case series (mainly selection bias and retrospective analysis) we hope that it stimulates further research in this area particularly in light of its theoretical support from the previous literature on the serotonin system and crying. From a clinical perspective an inability to cry may diminish the tolerability and acceptability of treatment for the patient, particularly in light of the popularly accepted ‘cathartis model’ of crying despite the fact that the current literature does support the popular idea that being unable to cry is emotionally harmful. From a scientific perspective, the clinical dissociation of emotional experience and expression suggests a distinction between underlying cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms and provides a basis for further prospective studies in this area.

Conflicto de interesesJorge Holguin Lew ha sido conferencista remunerado en actividades académicas financiadas por Astra Zeneca, Lundbeck, Jannssen, Novartis, Eli-Lilly y Servier. Ha asistido a congresos y actividades académicas en donde su desplazamiento, inscripción y estadía ha sido financiada por estas casas farmacéuticas. No posee acciones de ninguna de estas compañías ni recibe honorarios por afiliación laboral directa.