Social media use is growing in Latin America and is increasingly being used in innovative ways. This study sought to characterise the profile of social media users, among primary care patients in Colombia, and to assess predictors of their use of social media to search for health and mental health information (searching behaviour).

MethodsAs part of a larger scale-up study, we surveyed 1580 patients across six primary care sites in Colombia about their social media use. We used chi-square and Student’s t-tests to assess associations between demographic variables, social media use and searching behaviour, and a Chi-square Automatic Interaction Detector (CHAID) analysis to determine predictors of searching behaviour.

ResultsIn total, 44.4% of respondents reported that they were social media users. Of these, 35.7% used social media to search for health-related information and 6.6% used it to search for mental health-related information. While the profile of individuals who used social media to search for health-related information was similar to that of general social media users (the highest use was among women living in urban areas), the presence of mental health symptoms was a more important predictor of using social media to search for mental health-related information than demographic variables. Individuals with moderate-severe symptoms of anxiety reported a significantly higher percentage of searching than individuals without symptoms (12.5% vs. 5.2%).

ConclusionsGiven that some individuals with mental health disorders turn to social media to understand their illness, social media could be a successful medium for delivering mental health interventions in Colombia.

El uso de las redes sociales está creciendo en América Latina y de manera cada vez más innovadora. Este estudio busca caracterizar el perfil de los usuarios de las redes sociales entre los pacientes de atención primaria en Colombia y evaluar los predictores de utilización de las redes sociales para buscar información de salud y salud mental (comportamiento de búsqueda).

MétodosComo parte de un estudio de scale-up, se encuestó a 1.580 pacientes en 6 sitios de atención primaria en Colombia sobre usos de las redes sociales. Se aplicaron las pruebas de la χ2 y de la t de Student para evaluar asociaciones entre variables demográficas, uso de redes sociales y comportamiento de búsqueda, y un análisis de Chi-square Automatic Interaction Detector (CHAID) para determinar predictores de comportamiento de búsqueda.

ResultadosEl 444% de los encuestados informaron que eran usuarios de las redes sociales. El 357% de los usuarios de las redes sociales las utilizaron para buscar información relacionada con la salud y el 6,6%, para buscar información relacionada con la salud mental. Si bien el perfil de las personas que utilizaron las redes sociales para buscar información relacionada con la salud fue similar al de los usuarios de las redes sociales en general (el mayor frecuencia se dio entre las mujeres que vivían en áreas urbanas), la presencia de síntomas de salud mental fue un predictor más importante de emplear las redes sociales para buscar información relacionada con la salud mental que variables demográficas; los individuos con síntomas de ansiedad moderados-graves tuvieron un porcentaje significativamente mayor de búsquedas informadas que los individuos sin síntomas (el 12,5 frente al 5,2%).

ConclusionesDado que algunas personas con trastornos de salud mental recurren a las redes sociales para comprender su enfermedad, estas podrían ser un medio exitoso para ofrecer intervenciones de salud mental en Colombia.

The use of social media, internet-based applications made up of consumer-generated content that can be easily shared and accessed by other users, is widespread and continually growing, with a total of 3.96 billion social media users, representing 42% global penetration.1 The use of social media is expanding in both high income and low and middle-income countries (LMICs).1,2 The increasing presence of social media across the world creates a unique opportunity to easily deliver information to a wide audience.3 Although there are limited studies on the use of social media to deliver health information and interventions, those that do exist show promise across a variety of settings. Social media has been used to identify health information not reported to health departments, as a form of surveillance and information sharing, and as a means of targeting vulnerable populations and health risk behaviors, particularly among stigmatized populations with sensitive health conditions.4–8

In the healthcare setting, studies show that social media has the potential to expand patient engagement and education through allowing patients to share their experiences, reach out to peers and providers, and obtain information about their medical conditions.3 Moreover, studies have shown that social media can be effective at targeting and changing individuals’ behaviour. For example, the intervention, Get Yourself Tested (GYT), a social media-based sexually transmitted disease (STD) testing campaign, led to a 71% increase in STD testing nationwide.8 However, the majority of these studies have focused on physical illnesses, such as cholera, dengue, E. coli, and HIV/AIDs, and there are limited studies on the use of social media to deliver mental health interventions.4 The studies that do exist on this topic were conducted in high-income countries (HICs), such as Australia, where 47% of students reported that they would use online social networks to address their mental illnesses.4 In the United States, one study on the use of social media to create peer-to-peer support networks for individuals with serious mental illnesses found that these social media networks had the potential to help individuals challenge stigma, increase consumer activation, and provide opportunities for intervention-delivery.9 These studies demonstrate that individuals in HICs post information about their mental illnesses on social media, such as Twitter and Facebook, and would feel comfortable using social media interventions for their mental health disorders.4,9

Latin America shows promise as one region where social media-based health interventions could be effective; there is 63% social media penetration and 115% mobile connectivity, which represents more than one mobile phone per-person.1 In a literature review of studies on the use of social media in the context of health in Latin America, recurrent topics included tobacco and HIV/AIDs.10 An example of one of these studies that used social media to address HIV/AIDs was the HOPE study in Peru.11 Young et al.11 used peer-led Facebook groups to share messages and information about the importance of HIV prevention and testing, which led to an almost 3-fold increase in HIV testing in the region. However, few studies within LMIC-settings have explored the use of social media for searching for health or mental health-related information.

A country in Latin America with widespread social media use and a need for the proliferation of mental health interventions is Colombia. In Colombia, 9.1% of the population above the age of 18 meet DSM-IV criteria for any mental health disorder at some point during their lifetime, yet less than half of individuals presenting with a mental health disorder in the past 12 months received care.12 Moreover, in Colombia, there are more than 28 million social media users (57% penetration), and there has been a 17% growth in active social media users since 2016.1 Social media is used in Colombia in a variety of health and non-health related domains, such as by politicians, journalists, and health authorities. Health authorities in Colombia have a presence on three main social media channels: Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.10,13,14 Moreover, Ospina-Pinillos et al. recently conducted an exploratory study to adapt and test a web-based mental health eClinic for Colombian adolescents, which demonstrates the potential for using online platforms for delivering mental healthcare.15 However, although social media is widely used in Colombian society, as far as we know, social media has not been used to deliver mental health interventions.

Before proceeding with the development of a social media-based intervention, it is necessary to understand who uses these platforms, how they are used, and whether these platforms are used for seeking information about health and mental health. Consequently, as part of the formative work of a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-funded study that is scaling-up the screening and treatment for depression and mental health disorders within the primary care setting in Colombia, we conducted a survey across six sites in Colombia to better understand the landscape of technology usage and the demographic characteristics of those who use technology and social media. This paper seeks to characterise the profile of social media users in Colombia, and to identify demographic predictors of the use of social media platforms to search for health and mental health information. Through these analyses, we will identify demographic subsets of the population who could potentially benefit from a targeted social media-based mental health intervention.

MethodsSurvey sites and participant recruitmentParticipants were recruited to complete the survey, using non-probability quota sampling, from six primary care hospitals across Colombia, ranging from urban to rural and public to private. Participants were all 18 years old or older. Specifically, the healthcare centers included in this study were: site 1 (an urban ambulatory healthcare center in Bogotá), site 2 (an urban regional hospital that serves over 200,000 individuals in the state of Boyacá) site 3 (a rural primary care center, covering a population of 14,000), site 4 (a rural clinic that provides care to both urban and rural populations), site 5 (a rural, local hospital that provides care to a small town and highly dispersed rural population), and site 6 (a rural clinic that coordinates mental health services for 47 municipalities in the province). At each primary care site, a research assistant asked patients if they would be willing to complete the survey during their time in the waiting room before their medical appointment. The research assistant explained the nature of the tablet-based survey to participants and was available to supervise and answer questions as needed. The survey was self-administered, anonymous, and generally took between 10 and 15 min to complete. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Institutional Review Boards at Dartmouth College in the U.S. and Javeriana University in Colombia.

Survey instrumentThe survey that was used in this study sought to examine the extent to which patients in primary care hospitals in Colombia use Internet, mobile devices, such as smartphones (e.g., iPhone, Android, Blackberry), and tablet computers (e.g., iPad) to search for medical and health information. The survey included questions related to the use of social media to search for health information, such as, “have you ever used social media (e.g., Facebook) to search for information about your health” and “have you ever used social media (e.g., Facebook) to search for information about your mental health.” Through this survey, we intended to 1) Evaluate patients’ socioeconomic characteristics and their possible relation to patterns of technology use 2) Establish healthcare service use of patients in the primary care network and 3) Assess patients’ mobile device use for finding medical information related to general health and mental health. Specifically, the survey asked questions about facilitators of mobile device use in medical information seeking, barriers to access, internet connection conditions, familiarity with medical resources, and most frequently used resources. Research team members designed the survey questions based on prior similar surveys, such as technology assessments conducted in local hospitals and LMICs, as well as the Colombian mental health survey.12,16,17 The survey was implemented via a computerized survey engine (REDCap).18,19

Data analysisContinuous data were described through mean ± standard deviation, while relative and absolute frequencies were used for categorical variables. Associations between demographic characteristics and social media use or use of social media for searching for health or mental health information were assessed using Student’s t and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. These data were analyzed in Stata.20 Two classification tree models (CHAID) were used for detecting profiles of social media uses. p-Values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

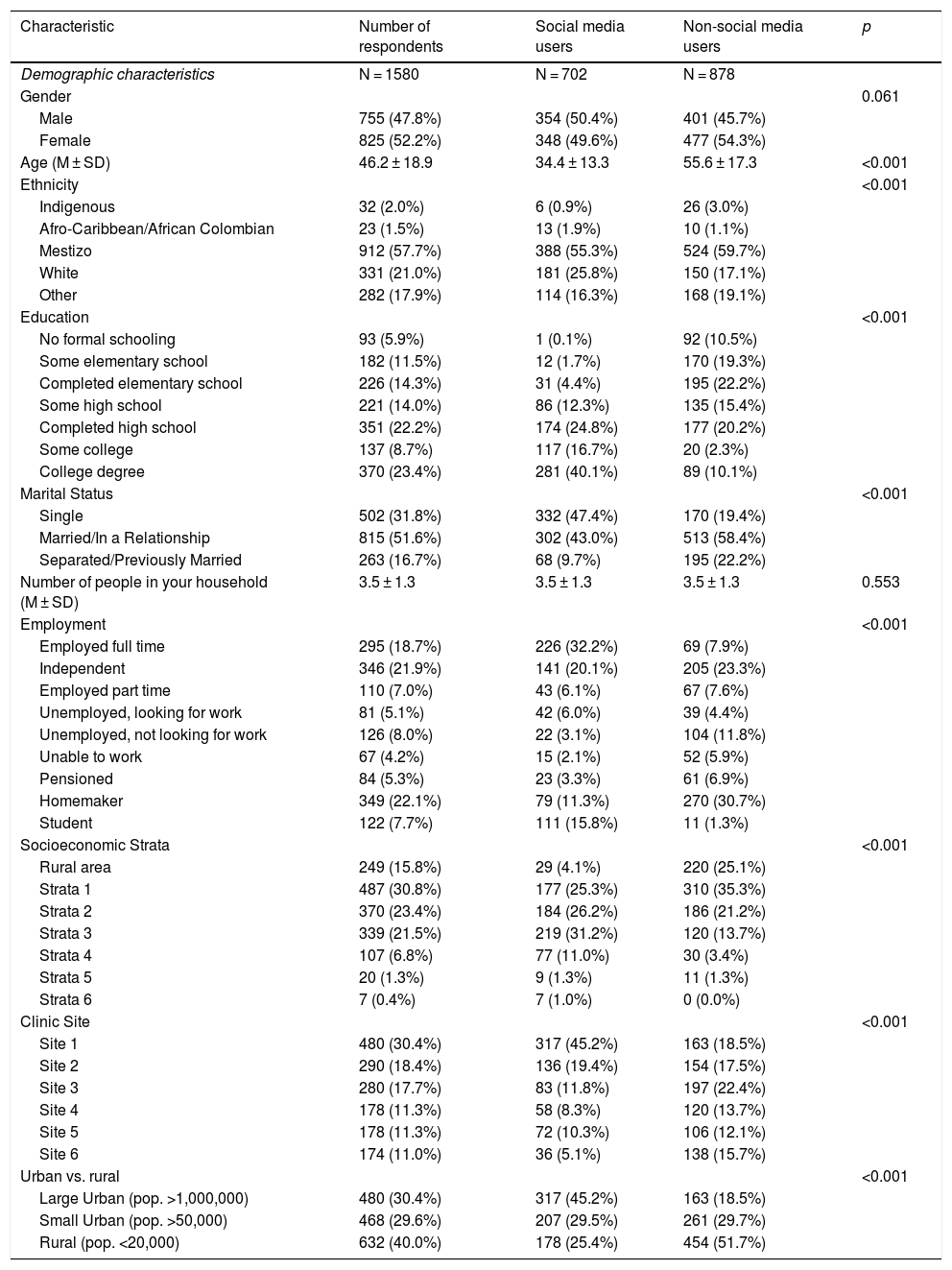

ResultsSample characteristicsA total of 1580 individuals responded to our survey. Respondents came from six different clinics: site 1 (n = 480; 30.4%), site 2 (n = 290; 18.4%), site 3 (n = 280; 17.7%), site 4 (n = 178; 11.3%), site 5 (n = 178; 11.3%), and site 6 (n = 174; 11.0%). 52.2% of respondents were female (n = 825). The average age of our respondents was 46.2 years ±18.9. The majority of our respondents identified as mestizo (mixed race) (57%), although respondents also identified as white (21.0%), indigenous (32%), Afro-Caribbean/Afro-Colombian (1.5%), and other (17.9%). Colombia officially classifies socioeconomic status through a strata system (with 1 being the lowest socioeconomic strata and 6 being the highest). The majority of our respondents came from the lowest two strata, which is representative of the sociodemographic makeup of Colombia; 487 (30.8%) came from strata 1 and 370 (23.4%) came from strata 2. For a complete list of the demographic characteristics of the respondents see Table 1.

Participants’ demographic characteristics.

| Characteristic | Number of respondents | Social media users | Non-social media users | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | N = 1580 | N = 702 | N = 878 | |

| Gender | 0.061 | |||

| Male | 755 (47.8%) | 354 (50.4%) | 401 (45.7%) | |

| Female | 825 (52.2%) | 348 (49.6%) | 477 (54.3%) | |

| Age (M ± SD) | 46.2 ± 18.9 | 34.4 ± 13.3 | 55.6 ± 17.3 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| Indigenous | 32 (2.0%) | 6 (0.9%) | 26 (3.0%) | |

| Afro-Caribbean/African Colombian | 23 (1.5%) | 13 (1.9%) | 10 (1.1%) | |

| Mestizo | 912 (57.7%) | 388 (55.3%) | 524 (59.7%) | |

| White | 331 (21.0%) | 181 (25.8%) | 150 (17.1%) | |

| Other | 282 (17.9%) | 114 (16.3%) | 168 (19.1%) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| No formal schooling | 93 (5.9%) | 1 (0.1%) | 92 (10.5%) | |

| Some elementary school | 182 (11.5%) | 12 (1.7%) | 170 (19.3%) | |

| Completed elementary school | 226 (14.3%) | 31 (4.4%) | 195 (22.2%) | |

| Some high school | 221 (14.0%) | 86 (12.3%) | 135 (15.4%) | |

| Completed high school | 351 (22.2%) | 174 (24.8%) | 177 (20.2%) | |

| Some college | 137 (8.7%) | 117 (16.7%) | 20 (2.3%) | |

| College degree | 370 (23.4%) | 281 (40.1%) | 89 (10.1%) | |

| Marital Status | <0.001 | |||

| Single | 502 (31.8%) | 332 (47.4%) | 170 (19.4%) | |

| Married/In a Relationship | 815 (51.6%) | 302 (43.0%) | 513 (58.4%) | |

| Separated/Previously Married | 263 (16.7%) | 68 (9.7%) | 195 (22.2%) | |

| Number of people in your household (M ± SD) | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 0.553 |

| Employment | <0.001 | |||

| Employed full time | 295 (18.7%) | 226 (32.2%) | 69 (7.9%) | |

| Independent | 346 (21.9%) | 141 (20.1%) | 205 (23.3%) | |

| Employed part time | 110 (7.0%) | 43 (6.1%) | 67 (7.6%) | |

| Unemployed, looking for work | 81 (5.1%) | 42 (6.0%) | 39 (4.4%) | |

| Unemployed, not looking for work | 126 (8.0%) | 22 (3.1%) | 104 (11.8%) | |

| Unable to work | 67 (4.2%) | 15 (2.1%) | 52 (5.9%) | |

| Pensioned | 84 (5.3%) | 23 (3.3%) | 61 (6.9%) | |

| Homemaker | 349 (22.1%) | 79 (11.3%) | 270 (30.7%) | |

| Student | 122 (7.7%) | 111 (15.8%) | 11 (1.3%) | |

| Socioeconomic Strata | <0.001 | |||

| Rural area | 249 (15.8%) | 29 (4.1%) | 220 (25.1%) | |

| Strata 1 | 487 (30.8%) | 177 (25.3%) | 310 (35.3%) | |

| Strata 2 | 370 (23.4%) | 184 (26.2%) | 186 (21.2%) | |

| Strata 3 | 339 (21.5%) | 219 (31.2%) | 120 (13.7%) | |

| Strata 4 | 107 (6.8%) | 77 (11.0%) | 30 (3.4%) | |

| Strata 5 | 20 (1.3%) | 9 (1.3%) | 11 (1.3%) | |

| Strata 6 | 7 (0.4%) | 7 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Clinic Site | <0.001 | |||

| Site 1 | 480 (30.4%) | 317 (45.2%) | 163 (18.5%) | |

| Site 2 | 290 (18.4%) | 136 (19.4%) | 154 (17.5%) | |

| Site 3 | 280 (17.7%) | 83 (11.8%) | 197 (22.4%) | |

| Site 4 | 178 (11.3%) | 58 (8.3%) | 120 (13.7%) | |

| Site 5 | 178 (11.3%) | 72 (10.3%) | 106 (12.1%) | |

| Site 6 | 174 (11.0%) | 36 (5.1%) | 138 (15.7%) | |

| Urban vs. rural | <0.001 | |||

| Large Urban (pop. >1,000,000) | 480 (30.4%) | 317 (45.2%) | 163 (18.5%) | |

| Small Urban (pop. >50,000) | 468 (29.6%) | 207 (29.5%) | 261 (29.7%) | |

| Rural (pop. <20,000) | 632 (40.0%) | 178 (25.4%) | 454 (51.7%) |

Seven hundred and two respondents (44.4%) in our study reported being social media users. Among social media users, the four most common types of social media use were Facebook (97%), YouTube (65.8%), Instagram (32.8%), and Twitter (28.5%). We found that there was a significant difference in age between social media users and non-social media users (p < 0.001); the mean age of social media users was 34.4 ± 13.3 years, while the mean age of non-social media users was 55.6 ± 17.3 years. Social media use also differed significantly based on urban versus rural location (p < 0.001). 45.2% of social media users were from a large urban population (pop. >1,000,000), while 29.5% and 25.4% of social media users came from small urban areas (20,000 > pop. >5000) and rural areas (pop. <20,000), respectively. There was also a significant difference (p < 0.001) in social media use based on level of education; overall, those with lower levels of education were more likely to be non-social media users; more than half of non-social media users only had up to an elementary school level degree (n = 457; 52.1%), 35.6% (n = 312) had completed some or all of high school as their highest degree, and 12.4% (n = 109) had completed some or all of college as their highest degree.

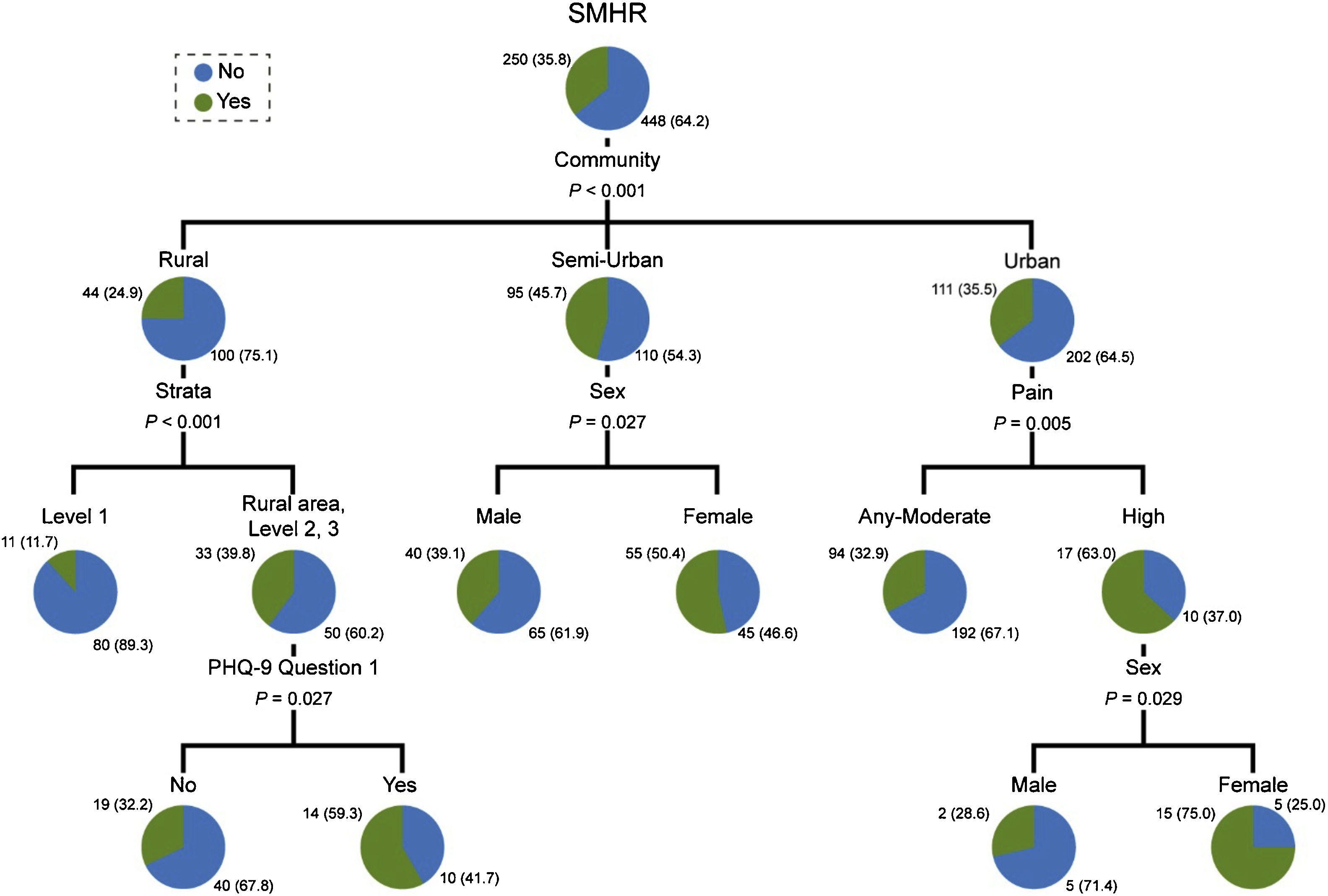

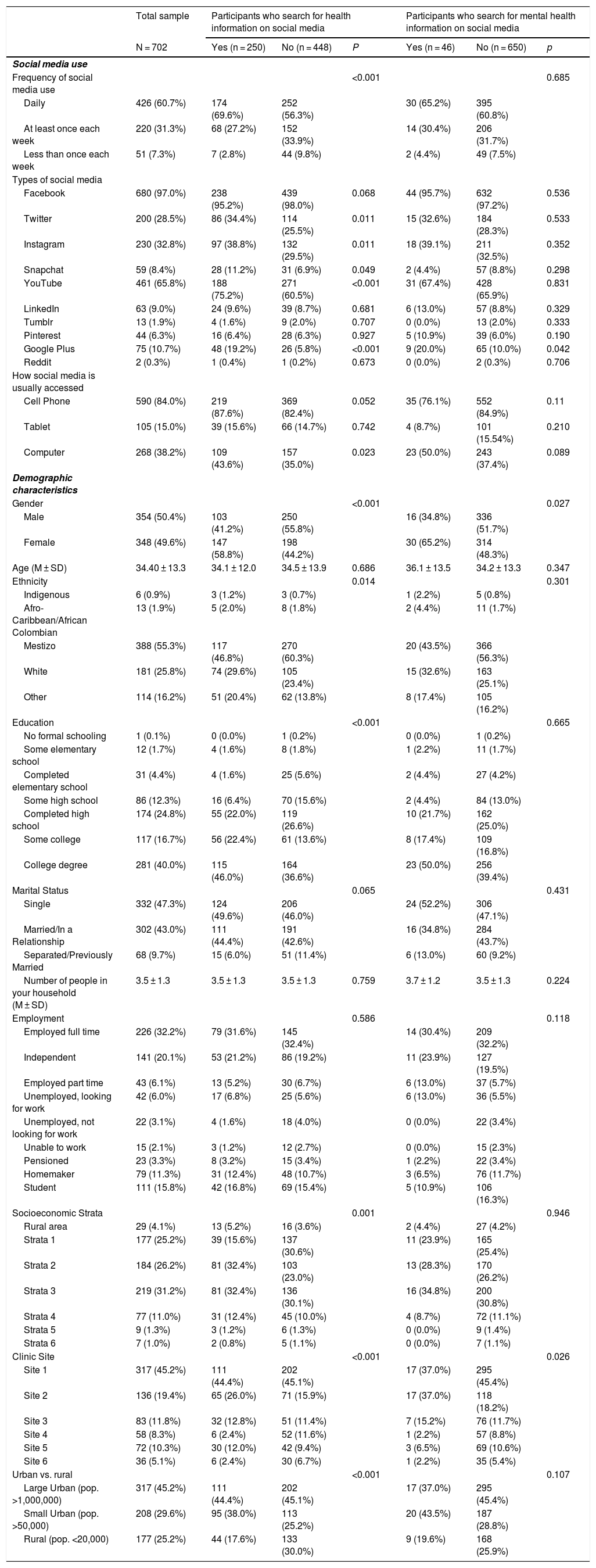

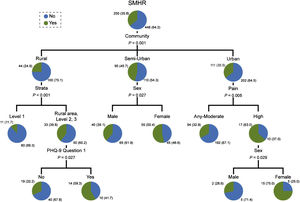

Searching for health and mental health information on social mediaAmong social media users within our sample (n = 702, 4 missing), 250 (35.6%, 95% CI from 32.2% to 39.1%) participants searched for health information on social media. Frequency of social media use differed significantly between those who searched for health information on social media and those who did not (p < 0.001). Participants who searched for health information on social media tended towards daily use (n = 174; 69.6%) more than those who did not use social media for this purpose (n = 252; 56.3%), and a greater percentage of those who did not search for health information on social media used social media at least once a week (33.9%) or less than once a week (9.8%) compared to those that did (27.2% and 2.8% respectively). There was also a significant difference in searching behaviour based on gender and education levels. Individuals who searched for health information on social media were more likely to be female (58.8%) and to have a college degree (46.0%) than men or individuals with less than a college degree. See Table 2 for a full list of comparisons. Overall, females living in urban areas who were suffering high levels of pain and females living in semi-rural areas had the highest percentages of social media use for searching for health information, 75.0% and 50.4%, respectively. Individuals living in rural areas with the lowest socioeconomic status (strata 1) had the lowest percentage of use, 11.7%. Fig. 1 depicts the classification tree for the use of social media use in health research (for searching for information about health).

Demographic characteristics and patterns of social media use among participants who search for information about their health and mental health on social media.

| Total sample | Participants who search for health information on social media | Participants who search for mental health information on social media | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 702 | Yes (n = 250) | No (n = 448) | P | Yes (n = 46) | No (n = 650) | p | |

| Social media use | |||||||

| Frequency of social media use | <0.001 | 0.685 | |||||

| Daily | 426 (60.7%) | 174 (69.6%) | 252 (56.3%) | 30 (65.2%) | 395 (60.8%) | ||

| At least once each week | 220 (31.3%) | 68 (27.2%) | 152 (33.9%) | 14 (30.4%) | 206 (31.7%) | ||

| Less than once each week | 51 (7.3%) | 7 (2.8%) | 44 (9.8%) | 2 (4.4%) | 49 (7.5%) | ||

| Types of social media | |||||||

| 680 (97.0%) | 238 (95.2%) | 439 (98.0%) | 0.068 | 44 (95.7%) | 632 (97.2%) | 0.536 | |

| 200 (28.5%) | 86 (34.4%) | 114 (25.5%) | 0.011 | 15 (32.6%) | 184 (28.3%) | 0.533 | |

| 230 (32.8%) | 97 (38.8%) | 132 (29.5%) | 0.011 | 18 (39.1%) | 211 (32.5%) | 0.352 | |

| Snapchat | 59 (8.4%) | 28 (11.2%) | 31 (6.9%) | 0.049 | 2 (4.4%) | 57 (8.8%) | 0.298 |

| YouTube | 461 (65.8%) | 188 (75.2%) | 271 (60.5%) | <0.001 | 31 (67.4%) | 428 (65.9%) | 0.831 |

| 63 (9.0%) | 24 (9.6%) | 39 (8.7%) | 0.681 | 6 (13.0%) | 57 (8.8%) | 0.329 | |

| Tumblr | 13 (1.9%) | 4 (1.6%) | 9 (2.0%) | 0.707 | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (2.0%) | 0.333 |

| 44 (6.3%) | 16 (6.4%) | 28 (6.3%) | 0.927 | 5 (10.9%) | 39 (6.0%) | 0.190 | |

| Google Plus | 75 (10.7%) | 48 (19.2%) | 26 (5.8%) | <0.001 | 9 (20.0%) | 65 (10.0%) | 0.042 |

| 2 (0.3%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0.673 | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.3%) | 0.706 | |

| How social media is usually accessed | |||||||

| Cell Phone | 590 (84.0%) | 219 (87.6%) | 369 (82.4%) | 0.052 | 35 (76.1%) | 552 (84.9%) | 0.11 |

| Tablet | 105 (15.0%) | 39 (15.6%) | 66 (14.7%) | 0.742 | 4 (8.7%) | 101 (15.54%) | 0.210 |

| Computer | 268 (38.2%) | 109 (43.6%) | 157 (35.0%) | 0.023 | 23 (50.0%) | 243 (37.4%) | 0.089 |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Gender | <0.001 | 0.027 | |||||

| Male | 354 (50.4%) | 103 (41.2%) | 250 (55.8%) | 16 (34.8%) | 336 (51.7%) | ||

| Female | 348 (49.6%) | 147 (58.8%) | 198 (44.2%) | 30 (65.2%) | 314 (48.3%) | ||

| Age (M ± SD) | 34.40 ± 13.3 | 34.1 ± 12.0 | 34.5 ± 13.9 | 0.686 | 36.1 ± 13.5 | 34.2 ± 13.3 | 0.347 |

| Ethnicity | 0.014 | 0.301 | |||||

| Indigenous | 6 (0.9%) | 3 (1.2%) | 3 (0.7%) | 1 (2.2%) | 5 (0.8%) | ||

| Afro-Caribbean/African Colombian | 13 (1.9%) | 5 (2.0%) | 8 (1.8%) | 2 (4.4%) | 11 (1.7%) | ||

| Mestizo | 388 (55.3%) | 117 (46.8%) | 270 (60.3%) | 20 (43.5%) | 366 (56.3%) | ||

| White | 181 (25.8%) | 74 (29.6%) | 105 (23.4%) | 15 (32.6%) | 163 (25.1%) | ||

| Other | 114 (16.2%) | 51 (20.4%) | 62 (13.8%) | 8 (17.4%) | 105 (16.2%) | ||

| Education | <0.001 | 0.665 | |||||

| No formal schooling | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | ||

| Some elementary school | 12 (1.7%) | 4 (1.6%) | 8 (1.8%) | 1 (2.2%) | 11 (1.7%) | ||

| Completed elementary school | 31 (4.4%) | 4 (1.6%) | 25 (5.6%) | 2 (4.4%) | 27 (4.2%) | ||

| Some high school | 86 (12.3%) | 16 (6.4%) | 70 (15.6%) | 2 (4.4%) | 84 (13.0%) | ||

| Completed high school | 174 (24.8%) | 55 (22.0%) | 119 (26.6%) | 10 (21.7%) | 162 (25.0%) | ||

| Some college | 117 (16.7%) | 56 (22.4%) | 61 (13.6%) | 8 (17.4%) | 109 (16.8%) | ||

| College degree | 281 (40.0%) | 115 (46.0%) | 164 (36.6%) | 23 (50.0%) | 256 (39.4%) | ||

| Marital Status | 0.065 | 0.431 | |||||

| Single | 332 (47.3%) | 124 (49.6%) | 206 (46.0%) | 24 (52.2%) | 306 (47.1%) | ||

| Married/In a Relationship | 302 (43.0%) | 111 (44.4%) | 191 (42.6%) | 16 (34.8%) | 284 (43.7%) | ||

| Separated/Previously Married | 68 (9.7%) | 15 (6.0%) | 51 (11.4%) | 6 (13.0%) | 60 (9.2%) | ||

| Number of people in your household (M ± SD) | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 0.759 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 0.224 |

| Employment | 0.586 | 0.118 | |||||

| Employed full time | 226 (32.2%) | 79 (31.6%) | 145 (32.4%) | 14 (30.4%) | 209 (32.2%) | ||

| Independent | 141 (20.1%) | 53 (21.2%) | 86 (19.2%) | 11 (23.9%) | 127 (19.5%) | ||

| Employed part time | 43 (6.1%) | 13 (5.2%) | 30 (6.7%) | 6 (13.0%) | 37 (5.7%) | ||

| Unemployed, looking for work | 42 (6.0%) | 17 (6.8%) | 25 (5.6%) | 6 (13.0%) | 36 (5.5%) | ||

| Unemployed, not looking for work | 22 (3.1%) | 4 (1.6%) | 18 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 22 (3.4%) | ||

| Unable to work | 15 (2.1%) | 3 (1.2%) | 12 (2.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (2.3%) | ||

| Pensioned | 23 (3.3%) | 8 (3.2%) | 15 (3.4%) | 1 (2.2%) | 22 (3.4%) | ||

| Homemaker | 79 (11.3%) | 31 (12.4%) | 48 (10.7%) | 3 (6.5%) | 76 (11.7%) | ||

| Student | 111 (15.8%) | 42 (16.8%) | 69 (15.4%) | 5 (10.9%) | 106 (16.3%) | ||

| Socioeconomic Strata | 0.001 | 0.946 | |||||

| Rural area | 29 (4.1%) | 13 (5.2%) | 16 (3.6%) | 2 (4.4%) | 27 (4.2%) | ||

| Strata 1 | 177 (25.2%) | 39 (15.6%) | 137 (30.6%) | 11 (23.9%) | 165 (25.4%) | ||

| Strata 2 | 184 (26.2%) | 81 (32.4%) | 103 (23.0%) | 13 (28.3%) | 170 (26.2%) | ||

| Strata 3 | 219 (31.2%) | 81 (32.4%) | 136 (30.1%) | 16 (34.8%) | 200 (30.8%) | ||

| Strata 4 | 77 (11.0%) | 31 (12.4%) | 45 (10.0%) | 4 (8.7%) | 72 (11.1%) | ||

| Strata 5 | 9 (1.3%) | 3 (1.2%) | 6 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (1.4%) | ||

| Strata 6 | 7 (1.0%) | 2 (0.8%) | 5 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (1.1%) | ||

| Clinic Site | <0.001 | 0.026 | |||||

| Site 1 | 317 (45.2%) | 111 (44.4%) | 202 (45.1%) | 17 (37.0%) | 295 (45.4%) | ||

| Site 2 | 136 (19.4%) | 65 (26.0%) | 71 (15.9%) | 17 (37.0%) | 118 (18.2%) | ||

| Site 3 | 83 (11.8%) | 32 (12.8%) | 51 (11.4%) | 7 (15.2%) | 76 (11.7%) | ||

| Site 4 | 58 (8.3%) | 6 (2.4%) | 52 (11.6%) | 1 (2.2%) | 57 (8.8%) | ||

| Site 5 | 72 (10.3%) | 30 (12.0%) | 42 (9.4%) | 3 (6.5%) | 69 (10.6%) | ||

| Site 6 | 36 (5.1%) | 6 (2.4%) | 30 (6.7%) | 1 (2.2%) | 35 (5.4%) | ||

| Urban vs. rural | <0.001 | 0.107 | |||||

| Large Urban (pop. >1,000,000) | 317 (45.2%) | 111 (44.4%) | 202 (45.1%) | 17 (37.0%) | 295 (45.4%) | ||

| Small Urban (pop. >50,000) | 208 (29.6%) | 95 (38.0%) | 113 (25.2%) | 20 (43.5%) | 187 (28.8%) | ||

| Rural (pop. <20,000) | 177 (25.2%) | 44 (17.6%) | 133 (30.0%) | 9 (19.6%) | 168 (25.9%) | ||

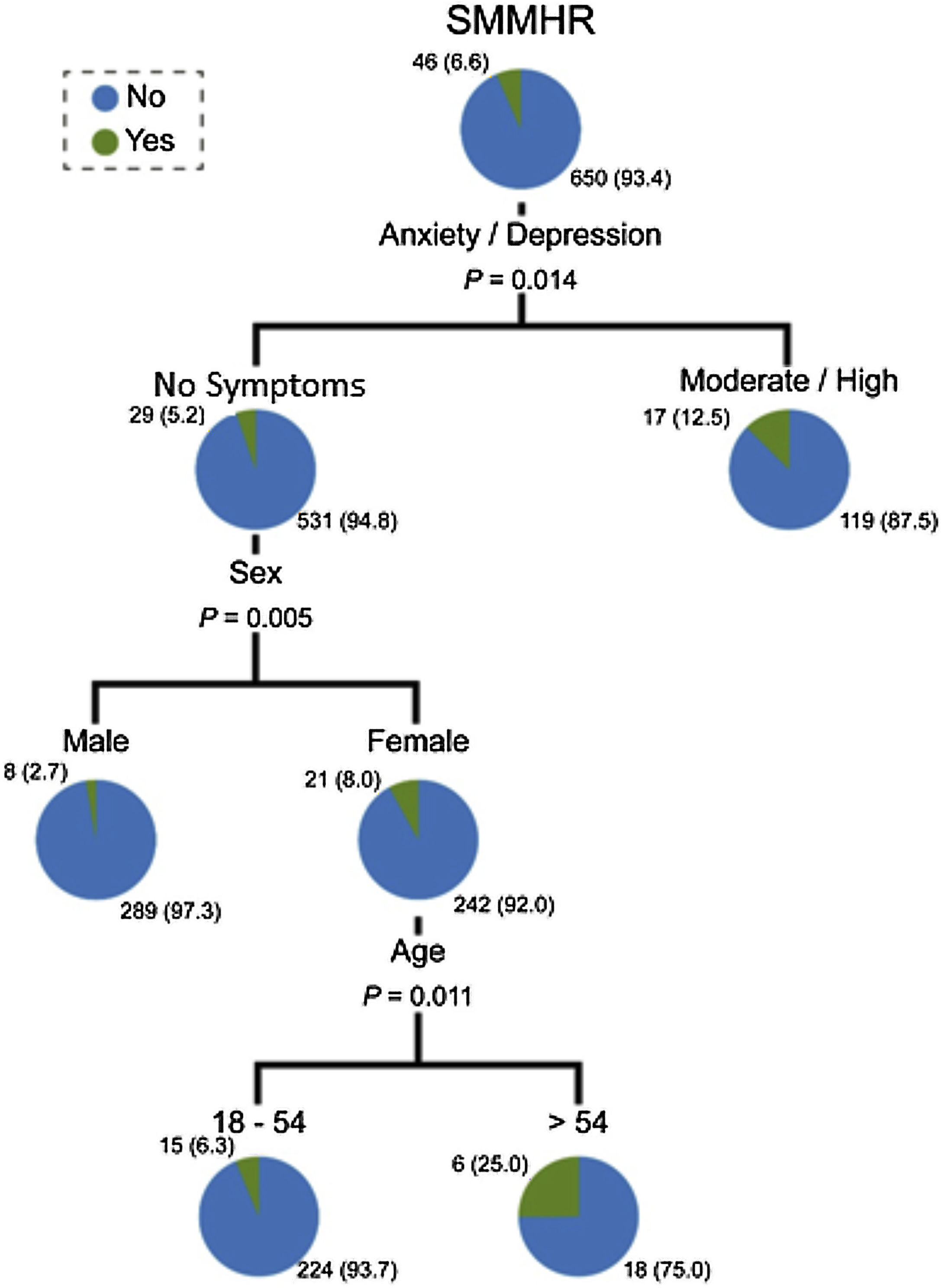

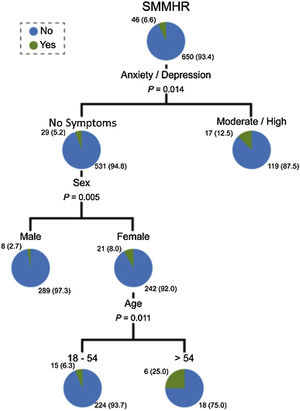

Our study also analyzed responses from social media users about if they searched for mental health information on social media. Overall, 46 participants (6.6%, 95% CI from 4.9% to 8.5%) used social media for this purpose. Within this sample, types of social media use were not significantly different between the two groups, except Google Plus; 20% of participants who searched for information about mental health on social media used Google Plus, versus 10% of participants who did not (p = .042). Gender was also statistically significant between the two groups; 65.2% of individuals who had used social media to search for mental health information were female, while only 48.3% of individuals who had not used social media for this purpose were female. Age, education, employment, socioeconomic status and setting (urban versus rural) were not significantly different between the two groups. Overall, the use of social media to search for information about mental health was more associated with symptoms than with social profiles. Although females who were older than 54 years and did not have anxiety symptoms had the highest percentage of reported searching (25%), individuals with moderate/high symptoms of anxiety had a higher percentage of reported searching than individuals without symptoms (12.5% vs. 5.2%, p = 0.014). Fig. 2 depicts the classification tree for the social media use in mental health research (for searching for information about mental health).

DiscussionThis study found a widespread use of social media in Colombia. As 44.4% of our respondents used social media, and 35.6% of our sample used social media to search for health information, these trends represent an opportunity to use this medium to deliver health and mental health interventions in Colombia. As demonstrated through interventions such as the Get Yourself Tested (GYT) campaign, social media can be particularly effective at reaching populations with socially stigmatized illnesses, like mental health disorders.4,8 Studies have found that although reforms have been made in many Latin American countries to reduce the stigma of mental illness, following the 1990 Caracas Declaration (a reform that called for the integration of mental healthcare into the primary healthcare system, the shifting of hospital-based care to community care, and the protection of rights for those with mental illness; see Caldas de Almeida & Horvitz-Lennon, 2010 for further reading), stigma still represents a major barrier for patients with mental disorders and their family members.21,22 Uribe-Restrepo et al. (2007) conducted focus groups and interviews with patients and their family members in Colombia about their experiences with lived stigma, and found that some of the major consequences and experiences of stigma are ostracism, rejection, demoralization, hopelessness, rejection, low self-esteem, and lower rates of seeking treatment.23 Consequently, social media, and the anonymity and connection to peers that it provides, could offer an important opportunity in Colombia to increase treatment and reduce the negative feelings associated with stigma among those with mental illness.

It is likely that in Colombia, social media-based interventions will be more effective with young individuals, versus older adults, as our data show that young Colombians are more likely to be social media users than older adults. Ethnicity, education level, socioeconomic status, and being from a rural versus urban area were also all significantly associated with social media use. In a systematic review of social media use for health interventions or surveillance, Charles-Smith (2015) found that different demographic groups may prefer different types of social media outlets, and determined that understanding how a population uses social media is an essential element in the success of a health intervention. Additionally, this systematic review found that adolescents are generally targeted using Facebook and Myspace, while adults are targeted using Twitter and specialized chat rooms.4 This study indicates the need for surveys, like ours, that seek to understand social media use among different demographics and demonstrates that mental health interventions in Colombia may vary in effectiveness based on population age and social media outlet.

Our study also found that those who search for health information on social media differ significantly from those who do not use social media for this purpose. Social media use for searching for health information was most prevalent among urban populations, among individuals with a higher socioeconomic status, and among individuals with higher education levels (p < 0.001). Additionally, individuals who use social media more frequently, females, and those with higher levels of education were more likely to use social media to search for health information (p < 0.001). Specifically, females, living in urban areas, and who were experiencing high levels of pain, were most likely of all respondents to use social media to search for health information. These results indicate that females living in Colombia’s major cities could be a good target for health interventions, and that females, in particular, turn to social media when they want to learn more about the illness and pain that they are experiencing.

Our results also highlight potential barriers for the use of social media to deliver health interventions to individuals living in rural areas and to individuals with lower levels of education, who may have reduced access to Wi-Fi, Internet, and devices, such as smartphones or computers, or may be illiterate, which could limit their access to and use of social media. Studies show that these populations, in particular, tend to suffer more in Colombia due to a paucity of mental healthcare providers in rural areas and lower quality subsidized healthcare.24 Although this barrier makes the current utility of social media for delivering interventions to these populations challenging, increasing trends of social media use and internet connectivity in Colombia may present future opportunities to use social media interventions for delivering health interventions to these underserved populations.1

Finally, our study found that severity of symptoms (related to anxiety or depression) was a more important predictor of using social media to search for information about mental health than sociodemographic profiles, although being female and above the age of 54 also played a role in searching behaviour. This finding indicates that in Colombia, individuals who experience mental illness often turn to social media to better understand their symptoms and information related to their illness. As a result, social media-based interventions or information campaigns show promise for extending the reach of care for individuals with mental illness. As indicated by the work of Ospina-Pinillos et al.,15 these interventions may be able to be adapted from HICs to the Colombian context to make mental healthcare more accessible and acceptable throughout the country.

The limitations of this study include the fact that non-probability sampling was used as the recruitment method for this survey. This method could have reduced the generalizability of our results to the general population of primary care users. Another limitation of this study was that surveys were self-administered on a tablet. As individuals who are less comfortable with technology may have chosen not to take the survey, due to the fact that it was administered on a tablet, answers to the surveys could have been skewed towards more frequent use of technology and social media. Finally, our population surveyed was also older (46.2 years+/-18.9) than the national average age in Colombia (30 years old), which could have also affected the generalizability our results, potentially skewing them towards a lower prevalence of social media use than in the general population.25 However, we aimed to address some of these potential issues of generalizability through our large sample (1580 participants) taken from primary care settings across Colombia.

ConclusionThis study makes strides towards understanding patterns of social media use among primary care users in Colombia, specifically how they use social media in relation to their general and mental health. These findings can inform the field of mental health intervention research, given the potential that social media has to reach a wide range of patients with mental health disorders, particularly those who might be uncomfortable seeking formal treatment. This study has found that primary care patients with moderate-severe mental health symptoms in Colombia use social media to learn more about their illness, demonstrating that a social media-based intervention for this population could be effective. The predictors of social media use highlighted in this study can be used by researchers, as they develop general health and mental health applications, to target populations in Colombia that may benefit most from social media-based interventions.

FundingResearch reported in this publication was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number 1U19MH109988 (Multiple Principal Investigators: Lisa A. Marsch, Ph.D. and Carlos Gómez-Restrepo, MD). The contents are solely the opinion of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or the United States Government.

Please cite this article as: Bartels SM, Martinez-Camblor P, Naslund JA, Suárez-Obando F, Torrey WC, Cubillos L, et al. Caracterización de los usuarios de las redes sociales dentro del sistema de atención primaria en Colombia y predictores de su uso de las redes sociales para comprender su salud. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:42–51.