Access to healthcare services involves a complex dynamic, where mental health conditions are especially disadvantaged, due to multiple factors related to the context and the involved stakeholders. However, a characterisation of this phenomenon has not been carried out in Colombia, and this motivates the present study.

ObjectivesThe objective of this study was to explore the causes that affect access to health services for depression and unhealthy alcohol use in Colombia, according to various stakeholders involved in the care process.

MethodsIn-depth interviews and focus groups were conducted with health professionals, administrative professionals, users, and representatives of community health organisations in five primary and secondary-level institutions in three regions of Colombia. Subsequently, to describe access to healthcare for depression and unhealthy alcohol use, excerpts from the interviews and focus groups were coded through content analysis, expert consensus, and grounded theory. Five categories of analysis were created: education and knowledge of the health condition, stigma, lack of training of health professionals, culture, and structure or organisational factors.

ResultsWe characterised the barriers to a lack of illness recognition that affected access to care for depression or unhealthy alcohol use according to users, healthcare professionals and administrative staff from five primary and secondary care centres in Colombia. The groups identified that lack of recognition of depression was related to low education and knowledge about this condition within the population, stigma, and lack of training of health professionals, as well as to culture. For unhealthy alcohol use, the participants identified that low education and knowledge about this condition, lack of training of healthcare professionals, and culture affected its recognition, and therefore, healthcare access. Neither structural nor organisational factors seemed to play a role in the recognition or self-recognition of these conditions.

ConclusionsThis study provides essential information for the search for factors that undermine access to mental health in the Colombian context. Likewise, it promotes the generation of hypotheses that can lead to the development and implementation of tools to improve care in the field of mental illness.

El acceso a servicios de salud implica una dinámica compleja, donde las condiciones de salud mental se ven especialmente desfavorecidas, debido a múltiples factores relacionados con el contexto y los actores involucrados. Sin embargo, en Colombia no se ha caracterizado este fenómeno, lo cual motiva el presente estudio.

ObjetivosEl objetivo de este estudio fue explorar las causas que afectan el acceso a servicios de salud para la atención de la depresión y el consumo riesgoso de alcohol en Colombia, de acuerdo con diversos actores involucrados en el proceso de atención.

MétodosSe condujeron entrevistas en profundidad con profesionales de la salud, administrativos, usuarios y representantes de organizaciones comunitarias en salud, en cinco instituciones de atención de primer y segundo nivel en tres regiones de Colombia. Posteriormente, para describir el acceso a la atención en salud para depresión o uso riesgoso de alcohol, se codificaron extractos de entrevistas y grupos focales a través del análisis del contenido, consenso de expertos y teoría fundamentada. Se crearon cinco categorías de análisis: educación y conocimiento de la condición de salud, estigma, falta de entrenamiento de profesionales de la salud, cultura y estructura o factores organizacionales.

ResultadosCaracterizamos las barreras para la falta de reconocimiento de las condiciones en salud mental que afectan el acceso a la atención de depresión o consumo riesgoso de alcohol de usuarios, profesionales de la salud y personal administrativo de cinco centros de atención primaria y secundaria en Colombia. Los grupos identificaron que la falta de reconocimiento de la depresión se relaciona con la poca educación o conocimiento de la población sobre esta condición, estigma y falta de entrenamiento de los profesionales de la salud, así como a la cultura. Para el consumo riesgoso de alcohol, los grupos observaron que la baja educación y el escaso conocimiento sobre esta condición, así como falta de capacitación de profesionales de la salud y la cultura afectan su identificación, y por lo tanto, el acceso a la atención en salud. Ni factores estructurales ni organizacionales parecieron tener un rol en el reconocimiento o autoreconocimiento de estas condiciones.

ConclusionesEste estudio suministra información esencial sobre los factores que afectan el acceso a la salud mental en el contexto colombiano. Asimismo, promueve la generación de hipótesis que pueden llevar al desarrollo e implementación de herramientas para mejorar la atención en el ámbito de la enfermedad mental.

The healthcare services access process is such a complex and diverse dynamic, that various models or schemes have been proposed to assess and interpret it.1 Irrespective of their advantages or disadvantages, all of the models focus on the patient, who is the actor promoting such dynamic.2,3 One of these models was proposed by Penchansky and Thomas.4 It does not provide a specific definition of healthcare access but disaggregates the process into different components, where healthcare access is the result of the interrelation or adjustment between its components (see Fig. 1). The assessment of healthcare access by components facilitates its characterization as a process.5 This model has been used in previous studies of the dynamics of healthcare access in different types of pathologies have been conducted, including mental health conditions.6,7

The assessment of healthcare access dynamics for mental health conditions has been increasing, not only in the agendas of health providers, but also in those of governments, organizations, and the general population.8–10 This trend lies in the increasing awareness about the burden of these conditions and their impact on the patients, caregivers and society. However, within the model of Penchansky and Thomas,4 the healthcare access phenomenon for mental health conditions has some peculiarities, in comparison to other conditions. For example, healthcare access among patients with mental health conditions would be particularly affected by low acceptability due to the social implications of the diagnosis for the patients, the stigma and segregation, the repercussions in economic aspects, and its relationship with poverty.11–13 It has also been observed that, compared to other conditions, the component of availability is at disadvantage for mental health conditions, given the scarcity of resources for its care. Resources are understood as the investment of financial capital in public policies, infrastructure, such as hospital centers and the number of hospitals, beds intended exclusively for patients with mental health conditions, and health professionals specialized in this area.8,14

Additionally, it has been previously identified that the lack of recognition of the mental health conditions among patients is a limiting factor for healthcare access, even in countries with high resources invested in health.15 Growing evidence shows that patients often do not recognize or underestimate the impact of mental health conditions in their overall health. In a study conducted within the framework of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Mental Health Survey,16 data from national surveys of 24 countries with different income levels was used to identify which barriers hinder the access to healthcare services. Data from patients who had been diagnosed with any type of mental health condition in the last twelve months was used, using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) survey. The most frequent barrier was not perceiving the need to be treated medically (between 56.4–99.3%), followed by attitudinal barriers (between 50.1–80.3%). When delving into the group of attitudinal barriers, it was observed that the most common factors were the perception that patients should be able to overcome the condition by themselves and that the disease was not so severe.16 At the local level, the 2015 Colombian National Mental Health Survey (ENSM, in Spanish) among participants aged 45 years old or older, about a third of the respondents reported a mental issue, but only 34% of them obtained any type of care; the leading cause for not receiving care was the lack of patient intiative to seek care. Among young adults (18–44 years old), 36.1% reported any mental issue, but only 38% of them had received some assessment by a health professional. Regarding participants aged 18 years old or younger, 64.8% and 52% did not seek healthcare services despite mental health issues were observed in 51.5% of the adolescents (12–17 years) and 55.4% of the children (7–11 years). The reason for not consulting was not assessed in this age group.17

There are other barriers in healthcare access among system actors, as a consequence of the lack of integration between the system actors, because the mental health conditions usually do not manifest with evident physical signs, but on the contrary, the signs must be recognized and identified by the patient and expressed to healthcare professionals.18,19 Other reasons hindering healthcare access for mental health issues, which have been described both among patients and healthcare professionals, include a lack of knowledge about what mental health conditions are, how they can be detected, and stigma or other negative cultural associations surrounding them.

In order to explore which components of the model behave as access barriers for mental healthcare services, and to explore why these barriers arise, this qualitative study was conducted with healthcare professionals, administrative staff, and patients from primary and secondary care sites in five municipalities of Colombia. We explored the role of these components in healthcare access for two of the most prevalent mental health conditions in Colombia, according to the ENSM 201517: depression and unhealthy alcohol use. We obtained the information through qualitative in-depth interviews and focus groups with each of the groups listed above at every site. This study focused on primary and secondary care sites because, in the Colombian health model, this is the gateway to health services, making it a strategic point for the recognition of mental health conditions.

MethodsThis study was conducted within the framework of the Comprehensive Detection and Attention of Alcohol Depression and Abuse in Primary Care (DIADA) project, an implementation study of a model for mental healthcare access in primary care. This qualitative study delved into the barriers to the recognition of mental health conditions and the impact on healthcare services access for these conditions in different municipalities of Colombia.

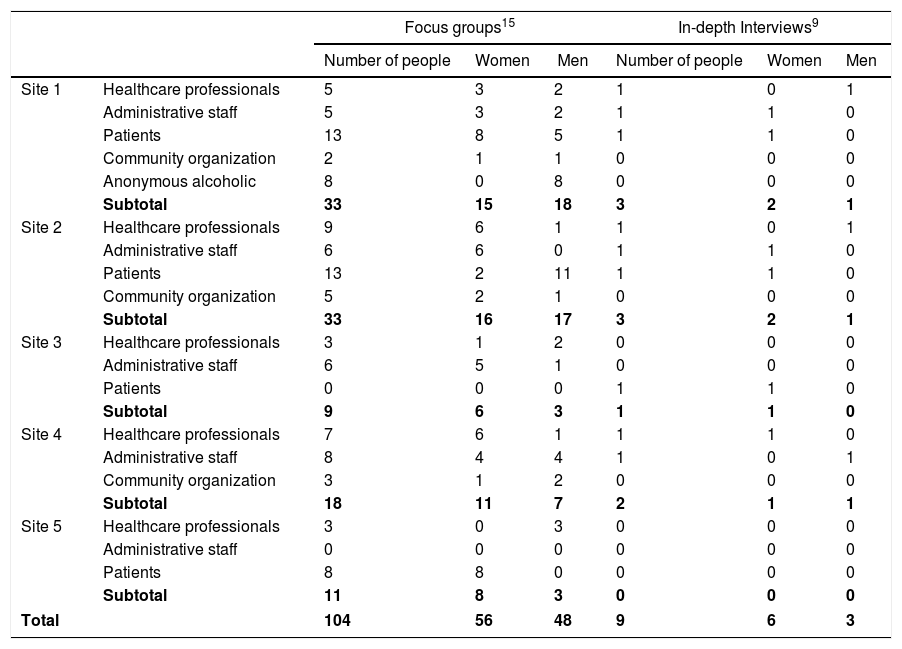

Fifteen focus groups and nine in-depth interviews were conducted for the present study, between 2017 and 2018, in 5 primary- and secondary-level health centers, located in both urban (Sites 1 and 3) and rural areas (Sites 2, 4 and 5). The focus groups and interviews were conducted by a team composed of a general practitioner, an anthropologist, and a psychologist or a psychiatrist. All of the focus groups and interview participants gave their informed consent to participate and to have the sessions recorded. The protocol of this study was approved by the research and ethics committees at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and Dartmouth College.

Each of the focus groups was recorded, notes were taken about the characteristics of the group, in order to complement the data collection. A trained research assistant coordinated the focus groups. During the focus groups, we asked the question: There may be some barriers to carry out the model (for mental health care in primary care) that we are implementing within the center. In this regard, what barriers exist, on the part of the center or the patients, that can be improved to increase the detection and treatment of patients with depression or unhealthy alcohol use who attend the medical appointments?

In-depth interviews were conducted, recorded and transcribedin order to complement the focus group responses and to learn other details that did not emanate from the focus groups. The interviewees had the role of critical informants, namely health professionals, administrative professionals, users, and representatives of community health organizations. The participants were chosen by convenience sampling, availability, and willingness to participate. Inclusion criteria for the foucs groups and interviews was that all participants were at least 18 years old, healthcare professionals and administrative staff had to be actively linked to the institutions visited and users belonged to the General System of Social Security in Health (SGSSS in Spanish) and should have sought care at the corresponding health center within the last twelve months due to symptoms compatible with depression or unhealthy alcohol use. No additional criteria besides age was established for the representatives of community organizations

Table 1 details number of foucs groups and in-depth interviews held by site and group.

Focus groups and in-depth interviews characteristics.

| Focus groups15 | In-depth Interviews9 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of people | Women | Men | Number of people | Women | Men | ||

| Site 1 | Healthcare professionals | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Administrative staff | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Patients | 13 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Community organization | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Anonymous alcoholic | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 33 | 15 | 18 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Site 2 | Healthcare professionals | 9 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Administrative staff | 6 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Patients | 13 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Community organization | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 33 | 16 | 17 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Site 3 | Healthcare professionals | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Administrative staff | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Patients | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 9 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Site 4 | Healthcare professionals | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Administrative staff | 8 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Community organization | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 18 | 11 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Site 5 | Healthcare professionals | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Administrative staff | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Patients | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 11 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 104 | 56 | 48 | 9 | 6 | 3 | |

We classified the interviews according to whether they were from an user of the health system, an administrative staff member, or a healthcare professional (medical doctor, psychiatrist, social workers). We stored the transcripts in a secure server at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. The research assistant that conducted the focus groups and the interviews deleted the names from the documents, leaving only a numeric list of participants (partipant1, etc.). These files were transcribed and then broken down into fragments to code them.

We conducted a categorical analysis using these fragments. The categories used were agreed upon and discussed a priori by three experts: an anthropologist, a psychologist and a psychiatrist with research experience. The defined categories were: education and knowledge of the condition, stigma, lack of training of health professionals, culture, and structural or organizational. Each expert coded the interview fragments in NVIVO 11. In order to verify the consistency of the classification and to evaluate the reliability of intercoders, a Cohen kappa coefficient was estimated for each pair of experts. We assumed there was consistency in the classification with a kappa greater than 0.60. When the kappa was lower than 0.60, we reviewed the coding obtained by each pair of experts, and we re-specified the classification, considering the definition of the categories described until a consensus was reached.

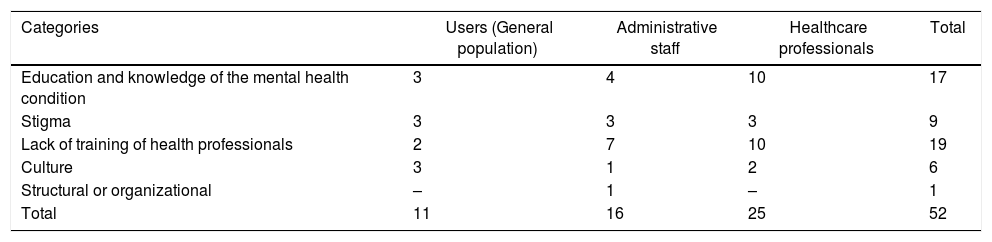

ResultsDepressionWe obtained 52 fragments with contents for depression. Table 2 shows the distribution of the fragments obtained according to the categorical analysis (Table 2).

Content themes on depression.

| Categories | Users (General population) | Administrative staff | Healthcare professionals | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education and knowledge of the mental health condition | 3 | 4 | 10 | 17 |

| Stigma | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| Lack of training of health professionals | 2 | 7 | 10 | 19 |

| Culture | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Structural or organizational | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| Total | 11 | 16 | 25 | 52 |

Users and healthcare professionals identified the category of education and knowledge of depression as a possible cause of non-recognition of the condition. A common point in most of the fragments was the misinformation that users have about the symptoms and course of the mental health conditions which, according to them, could prevent them from consulting in early stages: “But sometimes it happens that you do not inform yourself about your illnesses, because in my case at the beginning I was like someone told me that I had this and one gets the depression, yes, perhaps you don’t inform yourself about what is this disease and at that moment, the doctor doesn’t give you enough information, but then its when you start like to inform yourself, then it is something else, then one says, I will continue this treatment or I will do this or simply according to the years one has had the disease.” (Focus group: user association. Site 4)

The next three fragments illustrate the delay in treatment access that may occur due to lack of education and knowledge among patients and providers: "The thing is, see that the majority of people who consult here, they consult when they are already very depressed due to substance consumption and that, and they have even attempted suicide as a way to solve the situation, or as when they find themselves with the depression symptoms in their life that don’t let them work […].” (Interview: specialist in psychiatry. Site 2) “I believe that also the education that [it] is a disease like any other, it is worthwhile, I believe that with education one learns that it is a disease like any other and that it needs to be treated and that it needs to be identified.” (Focus group: administrative professionals. Site 4) “It is important to be able to make an early diagnosis, yes? To be able to detect the cases and to be able to do the handling on time, because let's say, this is an environment where in some occasions it has already been seen, but sadly one comes to know or to make an accurate diagnosis when things have already happened, yes? I mean, that is the importance or the reason why it is important to know about the topic, that all of our professionals and the professionals in the area know about the symptoms, to make an early diagnosis and be able to treat on time.” (Focus group: user. Site 1)

The following fragment highlights the contradiction between the perception of “not having anything” but “having something in the emotional part.” This apparent contradiction can be relevant for healthcare professionals, who may be able to recognize that the patient may have an emotional issue without assuming it is a disease. “You have absolutely nothing. Heart, head, I liked it, I didn't have to beg anyone to send me exams, everything, [the doctor] examined everything, and [the doctor] told me: you are well, the part that is failing you is your emotional part.” (Focus group: user. Site 1)

Additionally, the three interviewed groups identified stigma as a frequent cause of non-recognition or non-consultation for depression. Most of the participants mentioned that people facing these mental health conditions might be isolated or feel ashamed. “Here it is very complicated, see that here there are patients in fact who are already in a psychiatric process and the society does not understand well what happens, but perhaps [they assume] it is a tantrum on some occasions or that this [person] is already crazy, this is the crazy [one] and there is nothing to do. But there is not, like, a support; or, to have, for problems and mental disorders in the Colombian population, more education, yes, to guide and support certain issues. Then yes, this can also be a little factor.” (Interview: social worker. Site 4) “When you have a pain in a finger you do anything to cure that finger, but when you are depressed you don't get out of the depression, because you don't even feel like getting out of the depression, then it is very important that you remove that taboo.” (Focus group: user. Site 1)

Also, because these conditions are not well known by the general population, it is more difficult to ask a doctor for help in addressing them. The two following fragments illustrate the stigma that not only occurs in the community, but also in the healthcare system: “Mental illnesses to identify, depression or a bipolar disorder as a disease and that I, as a patient, as a family member, don't feel ashamed about this, I can perfectly present an illness and invent that I have diabetes and I'm not ashamed of telling it, but a person in his sixties says I have a bipolar disorder, so perhaps it is that stigma, it is an important task, it is an important challenge for the health system, I think people do not identify their problem because of that.” (Focus group: administrative professional. Site 4) “I think that the healthcare institutions must first work on the destigmatization of depression disease, because it is a disease.” (Focus group: user association. Site 1)

The most frequently mentioned category causing the lack of recognition of depression, even among the interviewed health professionals, was the lack of training of health professionals. In some fragments, it was mentioned that the lack of diagnostic suspicion would lead to late detection, when serious symptoms of depression have already appeared. “Well, because when they come to the office, they get here and the physician looks at him, [the doctor] does not see him depressed, but when he arrives, it is because he already tried to commit suicide.” (Focus group: administrative professional. Site 4) “Fortunately or unfortunately, the consumption for substances such as alcohol and depression are not within the 10 causes of morbidity, so, no emphasis is made, it is a diagnosis that will be ranked 30 out of the first 10 causes, if it were in the top 5 or in the top 10 probably, but then, it is a pathology that, although it is very common, it is very underdiagnosed and that is why the respective updates are not made, and it is already in the opinion of each professional if [the professional] wants to read, if [the professional] wants to update [him/herself] or whatever [the professional] wants to do about it.” (Focus group: health professional. Site 1) “I think it is also something cultural and political, when you start studying medicine and [they] always talk about the definition of health, the mental health part is included, but always the thick and the hard part is the bioclinical part and, let's say, when one is hypertense, diabetes (sic), that is the bulk. I would dare to say that when my brothers, who graduated about 20 years ago, studied medicine, they didn't talk so much about mental health, they didn't talk about depression so much, but maybe these were like those subjects that are a brief module and that's it, but it is not something that has always been addressed, like, in the clinical part.” (Focus group: health professional. Site 1)

Participants also described the normalization of depression symptoms occurring concurrently or masking other types of pathologies associated with depression: “Because the service provider institutions did not take that into account. For example, in a close case we had, there was depression in our relative and we wanted to take her to the doctor, ‘no, that doesn’t happen; that is simply age; that is simply postpartum’, and so on, he was given reasons, but they did not study it, that is, they knew that the person could have those symptoms of depression, but there was no follow-up, like: let's see what we can do with this depression, how can we help you get out of the depression frame. It is not simply that all women when they have had [children] have symptoms of postpartum depression, it is already normal, because they have symptoms of postpartum depression and now, nothing was done, they did not work with that. [To] things one has to give treatment so that one knows what will happen, that is, how we can overcome it.”(Focus group: user association. Site 1)

Patients or users of the healthcare system frequently mentioned culture as a barrier for depression recognition. In contrast, administrative staff workers and healthcare did not highlight this category as a possible explanation for why they are not consulted or why health care for depression is not often requested. In this category, it was identified that the symptoms of depression can be taken as a normal situation that can happen and that, if the doctor does not “worry, the person should not worry”: “People have not been accustomed to owning their health, but the owner of my health is the doctor.” (Focus group: administrative professional. Site 4) “But it is taken as normal. Or not, teenagers get depressed and that is it, it is assumed as a behavior pattern among certain sectors, and it is not like that, it is a thing to pay attention to. So nobody said, “Come look, let’s make an appointment. We can help you by this side.” No, “that's normal for teenagers, that's normal for mothers who just had children, that’s normal.” No, it is not normal, because it is something that makes me feel bad.” (Focus group: user association. Site 1) “I researched the disease, I started to see that my mom was also very depressed, so I started to get out of that depression for the same reason, to help her, for helping her, and then [there] have been like traumatic things, right? and one, then, sometimes thinks that the depression is something that happens and we do not go to the doctor, because what for, because one, being in depression, the doctor will not treat it, one says, no, but there are situations, there is a doctor for each case, but then one at that time does not plan to do it.” (Focus group: user. Site 4)

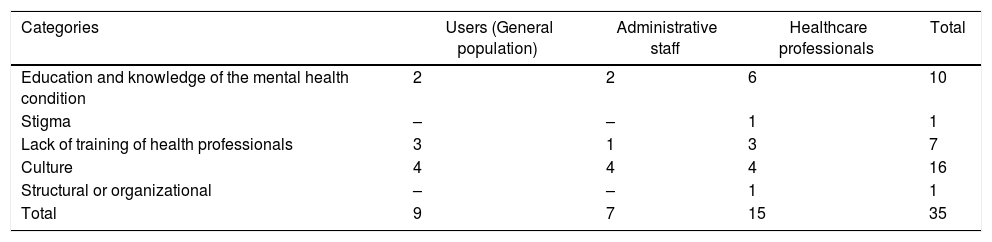

We coded 35 fragments with contents for unhealthy alcohol use, with more health professionals discussing barriers to recognition of unhealthy alcohol use than administrative staff. The most frequently identified cause for non-recognition was culture, while the structural and organizational category was the least frequently identified (Table 3).

Thematic of the contents on alcohol consumption.

| Categories | Users (General population) | Administrative staff | Healthcare professionals | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education and knowledge of the mental health condition | 2 | 2 | 6 | 10 |

| Stigma | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| Lack of training of health professionals | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Culture | 4 | 4 | 4 | 16 |

| Structural or organizational | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 9 | 7 | 15 | 35 |

Although the category of education and knowledge about the mental health condition was frequently mentioned by the three interviewed groups as a reason for the lack of recognition of unhealthy alcohol use, it was more frequently discussed by healthcare professionals. When exploring whether there was any common feature or factor in the extracts grouped in this category, we observed that healthcare professionals considered that users do not contemplate unhealthy alcohol use as a health condition. Although both patients and healthcare professionals do identify the consequences of alcohol consumption (for example, the occurrence of other diseases or their manifestations), a connection is not made between unhealthy alcohol use and the occurrence or manifestations of these diseases. “Alcohol abuse is something that I, at least, have not seen in the seven months I have been here, I have not seen a single patient who consults for alcoholism. And then say: ‘Well, I have high blood pressure, I have diabetes, I don't know what, I drink alcohol, I drink beer on the weekend, I like the drink, but I don't see the problem with that.’ So if the patient does not recognize his own body, one cannot try and tell him no.” (Focus group: healthcare professionals. Site 5) “‘The denial of the disease’, that is what has us at most, I received a message, when I was 22 years old and I got to 52 [years-old], because no, I handle the drink, ‘I leave that to the old degenerated men or… right? I don't fall asleep on the sidewalks…’ ; then, one waits until one hits against the world, until it does get to terrible bottoms, one does not land (sic), thank God I got to land.” (Focus group: Alcoholics Anonymous. Site 1).

All groups, especially healthcare professionals, identified the lack of training of healthcare professionals as a cause for non-recognition of unhealthy alcohol use. In general, it was mentioned that healthcare professionals tend to identify unhealthy alcohol use as a bad habit, rather than a health condition. Even during serious events in which unhealthy alcohol use is an obvious cause, such as in a traffic accident secondary to alcohol use or in a Mallory Weiss syndrome, an active search for this condition is not performed. “If a common person, when we give a small talk, who has nothing to do with health and is not a professional, who does not know, who does not know that alcoholism is a disease, it is fine, I did not know either, but we have been with doctors and there are some who do not know, or we go with psychologists who should know it and who say: ‘Is that a disease? [it is a bad habit], but a disease?’ Then it is not us, the World Health Organization and this whole issue.” (Focus group: Alcoholics Anonymous. Site 1)

The two following fragments illustrate how providers prioritize physical illness over unhealthy alcohol use as the factor underlying the patient’s conditions, potentially leading to delayed treatment and more severe consequences for patient’s wellbeing: “Perfect, but see, here is something very important (how good that you do this, how good), but there is something important here, when a traffic accident, for example, the guy arrives, he goes drunk driving a motorcycle and has a crash, he broke his leg, what do the doctors do in an emergency room when the patient gets there, they take care of his leg, right? ‘look, the man broke his leg’, its cast, its thing, but they do not see at the cause of the accident, the cause of the accident was the alcohol, and with the respect that you deserve, of course, because you have your future and how good you do that. So, here is something, if doctors, if the medical part saw the disease as the disease that it is, the alcohol as the World Health Organization says (min. 12), then it would be different, because you heal the guy’s leg and the guy gets his leg healed in three months and he goes well and will continue drinking, then in another accident he will arrive with both broken legs and a broken arm, and perhaps the guy kills himself; but if the doctors had more information about the disease of alcoholism, take it for granted that…” (Focus group: Alcoholics Anonymous. Site 1) “There is a lot of ignorance also among medical professionals, because the doctor tells the alcoholic…, the alcoholic will consult him not because of his alcoholism, but because he has gastritis, caused precisely by alcohol consumption and says: ‘don’t drink the whiskeys, have a beer that is softer’, yes?” (Focus group: Alcoholics Anonymous. Site 1)

The two following fragments illustrate how lack of recognition among providers may occur because of lack of training to identify the symptoms of these conditions: “In external consultation one see this. One perceives that a certain part of the population has something on a psychological level, something on a mental level. One realizes that they consult for other things of organic pathology, but that one… one identifies it, one knows it, but that one determines some behavior in front of that, no!.” (Focus group: healthcare professionals. Site 3) “There are some signs that are not formal triage, but that alert you that something else must be done, this patient has to go through or [the patient] has something, and we, in those criteria, we have nothing contemplated regarding mental health, we have very clinical criteria or perhaps not so clinical, but of very-user-symptoms (sic), that [the patient] says I have a lot of pain, the fact that [the patient] says he has a lot of pain, that is a symptom that the assistant will alert us. At least to call the specialist and say ‘Dr., here is something that can alert us’. I find it interesting to review what we can put of symptoms (sic) that the auxiliaries can identify, to at least asking for help and to say that is something that may be important to check, that we do not have contemplated, like there is pain, there are repeated consultations, there is alteration of vital signs, but really nothing of mental health". (Focus group: administrative professional. Site 1)

Finally, culture was mentioned and identified by the three interviewed groups as an important cause for not requesting or using health services for unhealthy alcohol use. The main common point in all the obtained fragments was the fact that, in Colombian society, alcohol consumption is seen as a normal and daily habit, which is accepted in homes and even introduced to minors in family events. Also, that alcohol is a legally and socially accepted substance. “I define this as a great monster, which pulls us down, but because it is socially accepted, nothing happens. The daddies are afraid of the consumption of marijuana, of parakeet, that they inject themselves, that they suck glue, whatever, in that we do get scared, but in the face of alcohol: tolerate it, control it, consume five….” (Focus group: Alcoholics Anonymous. Site 1) “And, in addition, as the boss says, it is also cultural; the boss says it’s like cultural, nobody is going to treat alcoholism, nobody, it is very difficult for a person to say I am an alcoholic and I am going to treatment.” (Interview: administrative professional. Site 4) “Culturally, alcohol abuse is an everyday thing. I believe that we grew up in an environment in which from families to people around our families have a culture of alcohol consumption. That before, I would believe, it is my perception, before it was more likely to give a child a drink at a meeting, as an act of ‘try’.” (Focus group: health professionals. Site 1)

Through the qualitative approach used in this study, we described the barriers that hinder the recognition of depression and unhealthy alcohol use and that affect the process of healthcare access for these conditions, according to various actors involved in this process (users, healthcare professionals, and administrative staff), in five primary and secondary care centers in Colombia. The identified barriers were similar between the interviewed actors and are consistent with those reported in studies conducted in Australia,20 United States21 and Europe,22 in which are also evident the difference between the care processes for mental health conditions compared to other types of conditions. Some of the categories that modify the care of patients with mental health conditions, and that were identified in this study, have been found in other studies, such as mental health literacy, stigma, culture and health care professionals’ knowledge of mental health conditions in Colombian population.

Mental health literacyMental health literacy has been defined in several ways. However, the one that is accepted with more regularity was proposed by Jorm et al.: “Knowledge and beliefs about mental illnesses that help in their recognition, management and prevention”.23 Patients’ education or, as it is known in the biomedical literature, “medical literacy” was one of the causes mentioned for the lack of access to health services, both due to depression and unhealthy alcohol use. This study showed that both healthcare professionals and users perceive that the population lacks knowledge about these conditions. Even in some interviews, it was mentioned that these are only recognized at advanced stages or when in crisis, for example, after a suicide attempt related to depression or under multiorgan sequelae associated with unhealthy alcohol consumption.

The lack of mental health literacy has been observed in different populations. In Australia, Jorm et al. conducted a national population study, in which they presented to their participants' vignettes with cases of depression and schizophrenia, in addition to behaviors and interventions that could help or worsen an individual’s condition. In their results, they found that only 39% and 27% of respondents adequately identified the case of depression and schizophrenia, respectively.23 This study design has been replicated in several countries and subsequently summarized in the review conducted by Angermeyer et al., which consistently found a lack of knowledge and information, as well as misconceptions, about people with mental health conditions.24

Misinformation and misconceptions about mental health conditions also encourage discriminatory behavior, such as prejudices, that are part of this dynamic that affect the patient care and treatment process.25 Additionally, poor literacy in mental health conditions can delay early diagnoses and proper treatment of these patients, thus increasing the recognition of the condition when it has already reached advanced stages. Such delays increase not only the impact of these conditions on the user and their family but also the associated costs and disability.26,27

Identifying health and mental health poor literacy as a cause of non-recognition for health issues has led to the definition of interventions and measures that could help to address the burden of these issues and the health status of patients. For example, in a population study conducted in Denmark with patients with cardiovascular disease, Aaby et al. applied questionnaires about the state of physical and mental health, knowledge about mental health conditions, attendance at control appointments, as well as related behaviors. In this population, patients with higher scores on scales of literacy and knowledge of their disease practiced healthier behaviors, such as physical activity and a healthy diet. They also had better physical and mental health, when compared with those with little knowledge about their conditions.28

The lack of mental health literacy among users can be explained because, often, they do not know about the existence of these mental health conditions or because they do not perceive difficulties caused by these conditions, due to a lack of introspection or recognition ability. Nevertheless, mental health literacy was a frequently mentioned aspect of the lack of recognition of both depression and unhealthy alcohol use, which is consistent with international literature.23,24,29,30 This finding may be attributed to the increasing demand of care for both physical and mental health conditions among patients in Colombia, probably secondary to the relevance gained by mental health in various recent public policies.31

StigmaStigma has historically been one of the most frequently identified barriers for mental healthcare access. Traditionally, mental health conditions have been associated with divine punishments, considered a family responsibility, or associated with poor resilience or mental weakness, so its occurrence has implied and continues to imply, although to a lesser extent, prejudices and discrimination.32

The definitions of stigma are multiple, and its approach is multidisciplinary, exceeding the scope of this study. For the objective of exploring the relationship between the recognition of mental health conditions and healthcare access, we use the model proposed by Henderson et al. about stigma and mental health conditions.12 This model disaggregates stigma into three components: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and organizational or structural stigma. Intrapersonal stigma or self-stigma refers to patients’ acceptance of stereotypes and ideas about mental health conditions, which impacts their self-esteem, and, therefore, on their need to be treated. Interpersonal stigma is closely related to mental health literacy, since it refers to the ideas, prejudices, and conceptions that families, friends, and the general population have, which can lead to discriminatory psychological and physical acts. Organizational or structural stigma refers to laws, policies, or social constructs that limit and compromise proper mental health care; for example, the lower number of mental health specialists or inequity in care among patients with and without mental health conditions.12,33 These aspects can be illustrated with an example frequently found in depression interviews, such as the loss of a pregnancy due to an abortion. The patient may blame herself, because she heard the abortion may have been caused by her sadness and depression (self-stigma); neighbors or acquaintances can walk away or talk behind her back about why the abortion occurred (interpersonal stigma); and the patient does not have professional mental health access to accompany her during the grieving process and, if any, appointments are very distant in time or the professional is at a considerable distance (structural stigma), which limits the consultation and health care that the patient requires.

Although stigma affects the recognition of most mental health conditions, some are more affected than others. In the study conducted by Dinos et al., qualitative interviews were conducted with patients with various mental health conditions. They found that patients with substance use disorders and psychosis more frequently suffered and were more affected by stigma. In contrast, patients with depression or anxiety disorders frequently mentioned paternalistic or condescending behaviors directed to them, as well as a higher degree of anticipatory stigma. Finally, the authors mentioned that stigma significantly affects acceptance of mental health condition recognition, as well as adherence and treatment continuity.34

It is worth noting that stigma was rarely or almost not mentioned as a barrier for the recognition or healthcare access for unhealthy alcohol use, unlike the findings of other studies about stigma and mental health conditions,35–37 while it was among the leading categories for lack of recognition of depression. This finding can be possibly attributed to the full acceptance and normalization of alcohol consumption in Colombia.

CultureThe definition of health as the mere absence of disease has transcended to include an integral vision of the human being, by considering their culture as part of what is known as social determinants. For this study, culture was defined as: “the values, norms, and beliefs under which the members of a group are governed, coexist and develop, and which can influence or be influenced by religious, gender, ethnicity, among others”.38 The set of values, norms, and beliefs that conform to the culture definition can and have been seen to modify the pathways in which individuals within a specific culture build their idea or construct of health and disease, thus creating substantial differences between different societies and countries. This mechanism is reflected in existing constructions and beliefs about mental health, such as those identified by Choudrhy et al.,25 who conducted a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies conducted in different countries to find perceptions or beliefs around mental health issues. One of the areas explored was the description of mental health issues. It was found that while in China, depression was considered normal for the population, in Nigeria, diseases, including depression, are attributed spiritual causes and supernatural forces.

On the other hand, it has been identified that the differences in these beliefs remain even after the individuals leave their country or geographical space of origin, as observed in countries where individuals from multiple cultures converge. Bignal et al. conducted a qualitative study aimed at exploring perceptions and ideas about mental health issues in four different cultural and ethnic groups in the United States (African-American, Hispanic, Asian, and American). These perceptions were grouped into different categories. The authors found that, concerning mental health conditions, perceptions among cultural groups were different. Thus, the most frequent perception of mental health conditions was of normalization among Asians, spirituality among Latinos and African Americans, and trauma among Americans. The author concluded that these cultural differences could explain the differences in requests for health services and should be considered when promoting health campaigns tailored to each cultural group.39

It is clear that the cultural and social context under which users grow is a significant determinant of their perception and understanding of the concept of health and disease, and from there, constructs such as social or legally accepted behaviors arise. To better understand this, we could explore the law regulation regarding the legality or illegality of the use of psychoactive substances among countries, especially for alcohol use. The law regulations about alcohol use are very diverse. However, the minimum age for alcohol use is legislated worldwide, varying from the non-definition of legal minimum age for consumption (China, Bolivia, Cameroon), over 18 years of age (Colombia, Italy, Egypt, Australia) and up to the undefined prohibition of consumption (Afghanistan, Iran, Bangladesh).40 However, depending on each country and culture, this legally defined age for alcohol consumption may or may not be socially accepted and, consequently, be reflected or not in the age at which alcohol consumption begins.

Culture was frequently mentioned as a barrier for recognition of both mental health conditions addressed in this study, although it seemed to be more relevant for alcohol consumption. This could be explained because alcohol consumption is usually performed in public, and it is associated with damage to third parties.40,41 Therefore, it is easier to identify the impact of culture in this condition.

Lack of training of health professionalsHealth services availability does not only refer exclusively to health structures and policies, but also to health professionals. Therefore, it is essential to have properly trained professionals providing these health services. However, a deficit in the number of specialists in mental health has been identified. In a study by Jacob et al., it was found that, worldwide, there are 1.2 psychiatrists per 100,000 inhabitants, a figure that varies depending on the region of the world: from 0.05 specialists in Africa to 9 psychiatrists for every 100,000 inhabitants in Europe.8 In Colombia, this proportion is 1 psychiatrist for every 200,000 people.17 In the face of such a deficit of doctors specializing in the assessment and treatment of mental health conditions, and given the burden and incidence of these conditions, with a projected increase in the coming years, it is expected that other health professionals get training in mental health. However, current literature shows that health professionals who are not psychiatrists struggle to recognize mental health conditions42 and to address them as health risk factors, which are important elements of primary care. In a systematic review conducted by Cepoiu et al. about the diagnosis of depression by non-psychiatrist doctors, they included mostly studies performed in primary care, followed by emergency room and in-hospital patients. They found a sensitivity of only 36.4% (95% CI 27.9–44.8) and specificity of 83.7% (95% CI 77.5–90) for the diagnosis of depressive among non-psychiatrist doctors, concluding that the diagnostic accuracy was very low.39 As this underdiagnosis and inaccuracy occur in depression, despite being among the most prevalent and best known mental health conditions in the general population, it is not uncommon to find such inaccuracies and recognition errors occurring in other mental health conditions.43,44

The lack of knowledge and training of healthcare professionals has been observed in several moments of the clinical process, from the diagnostic process to treatment. A study conducted by Wu et al.45 about knowledge of mental health conditions among general practitioners showed that less than 60% of the professionals identified the mental health condition when shown vignettes about the diagnosis and treatment of these conditions. However, 70% of the participants suggested offering the patient psychoactive drug treatment accompanied with a recommendation to speak or discuss the diagnosis with friends or family, instead of suggesting treatment by a mental health professional.

Studies have also been conducted to address the causes of health professionals’ lack of knowledge. For example, in the study conducted by Wilson et al., general practitioners in the United Kingdom (n = 282) were asked the reasons why the diagnosis of alcohol use disorder was not made. Most professionals indicated being very busy (63%), not having an adequate education on the diagnosis and management of this condition (57%), or beliving that it was not within their contractual obligations (49%). According to their results, the main points to intervene on were a lack of support in terms of time and human resources, and a lack of training.46

In our study, lack of knowledge among general practitioners was frequently recognized as a barrier to the recognition of both depression and unhealthy alcohol use. Probable causes are a lack of training or refresher courses for health professionals, as well as inadequate training in health and mental health conditions within the curricula of medical schools.

Our study has noteworthy limitations. First, our findings may not be generalizable to other contexts, such as different geographical locations. Although our study is multicenter, most of the study centers included in the study are located at the center of the country, known as Cundiboyacense region, where the alcohol use patterns and depression prevalence is different from other regions in the country. This implies that the perceptions of the interviewed population may be affected by this distribution of these mental health conditions. Second, our findings do not represent the perception of the overall population, as we included participants working at a primary and secondary care center or who were users of the center. Although these selection criteria allow for a more informed perspective regarding the factors that affect both recognition and healthcare access, due to depression and unhealthy alcohol use, our population and their opinions may be highly selected concerning the overall population. Lastly, since the purpose of the study was not masked, the interviewees (especially health professionals) could have been influenced by social desirability bias.

ConclusionThe present study provides essential information to understand the factors underlying the lack of recognition of mental health conditions and the low access to mental healthcare services within the Colombian context. The identified barriers may affect the effectiveness of evidence-based interventions for mental healthcare, as these factors may hinder either the self-recognition of patients suffering of these conditions or the recognition of the health professionals, thus preventing patients of obtaining the diagnosis and receiving the required treatment. Therefore, the implementation of such interventions need to take into account these factors to increase its effectiveness. Our findings can generate hypothesis leading to a better understanding of the mental healthcare access dynamics and thus, to possible improvements. The categories explored included mental health literacy, stigma, lack of training of health professionals, culture, and structure and type of organization. We provide an approach to depression and unhealthy alcohol use recognition barriers within the Colombian health system and comprehension about the recognition of mental health conditions among actors of the health system, including patients, healthcare professionals, and administrative staff.

FundingThe investigation reported in this publication was financed by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) via Grant# 1U19MH109988 (Multiple Principal Investigators: Lisa A. Marsch, PhD and Carlos Gómez-Restrepo, MD PhD). The content of this article is only the opinion of the authors and does not reflect the viewpoints of the NIH or the Government of the United States of America.

Conflicts of interestAuthors report not having any conflicts of interest. Dr. Lisa A. Marsch, one of the principal investigators on this project, is affiliated with the business that developed the mobile intervention platform that is being used in this research. This relationship is extensively managed by Dr. Marsch and her academic institution.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Restrepo C, Cárdenas P, Marroquín-Rivera A, Cepeda M, Suárez-Obando F, Miguel Uribe-Restrepo J, et al. Barreras de acceso, autoreconocimiento y reconocimiento en depresión y trastornos del consumo del alcohol: un estudio cualitativo. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2020.11.021