Stigma is a sociocultural barrier to accessing mental health services and prevents individuals with mental health disorders from receiving mental health care. The Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Colombia acknowledges that a great number of people with mental disorders do not seek medical aid due to stigma.

ObjectivesCharacterise the perceived stigma towards mental health among the stakeholders involved in the early implementation of the DIADA project [Detección y Atención Integral de Depresión y Abuso de Alcohol en Atención Primaria (Detection and Integrated Care for Depression and Alcohol Use in Primary Care)]. Explore whether the implementation of this model can decrease stigma. Describe the impact of the implementation on the lives of patients and medical practice.

Materials and methodsEighteen stakeholders (7 patients, 5 physicians and 6 administrative staff) were interviewed and a secondary data analysis of 24 interview transcripts was conducted using a rapid analysis technique.

ResultsThe main effects of stigma towards mental health disorders included refusing medical attention, ignoring illness, shame and labelling. Half of the stakeholders reported that the implementation of mental health care in primary care could decrease stigma. All of the stakeholders said that the implementation had a positive impact.

ConclusionsThe perceived stigma was characterised as social and aesthetic in nature. Communication and awareness about mental health is improving, which could facilitate access to mental health treatment and strengthen the doctor-patient relationship. Culture is important for understanding stigma towards mental health in the population studied.

El estigma hacia la salud mental impide que personas con enfermedad mental accedan a servicios de salud mental y se beneficien de un manejo médico integral. El Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia reconoce que personas con enfermedad mental no consultan al médico por varias razones, entre esas el estigma.

ObjetivoCaracterizar el estigma hacia la salud mental percibido por actores involucrados en la fase temprana de implementación del proyecto DIADA. Explorar si la implementación de este modelo podría ser una estrategia para disminuir el estigma. Describir el impacto de la implementación en la vida de pacientes y la práctica médica.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un análisis secundario de 24 entrevistas a 18 actores (7 pacientes, 5 médicos y 6 administrativos) implementando la técnica de análisis rápido.

Resultados: Entre los efectos principales del estigma se encuentra: rehusar la atención médica, no reconocimiento de la enfermedad, vergüenza y señalamiento. La mitad de los actores refieren que la implementación tuvo un impacto en el estigma. Todos los actores refieren que la implementación tuvo un impacto positivo.

ConclusionesEl estigma percibido es de carácter social y estético. La comunicación y la consciencia en torno a la salud mental mejora, lo cual podría facilitar el acceso al tratamiento en salud mental y fortalecer la relación médico-paciente. La cultura es importante para entender el estigma hacia la salud mental en la población estudiada.

Mental illness accounts for 7% of the world’s disease burden and almost one fourth of total global disability.1 Some studies show that the real impact of mental illness may be underestimated.2 In low and middle income countries, approximately 79–93% of people with depression have no access to treatment due to the unavailability of mental health professionals and the poor implementation of mental health programs. Even though the World Health Organization (WHO) promotes the integration of mental health services in primary care as a strategy to overcome such obstacles,3 care for mental health in low and middle income countries is often slow and ineffective due to various factors, including stigma towards mental health.4

According to the 2015 National Mental Health Survey, the lifetime prevalence of having a mental illness in Colombia is 10% in all ages.5 In adults, the lifetime prevalence of depression is around 5.3%, mainly impacting people between the ages of 18 and 44. The prevalence of risky alcohol use is 12% in this same age range.5 The Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Colombia recognizes that many people with mental illness refrain from seeking medical attention due to the stigma that surrounds mental health.6 In Colombia, law 1616 of 2013 recognizes, taking into account the 2030 agenda defined by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), “the necessity of making more efforts to reduce the stigmatization of the mentally ill and offer mental health services to the population”.7 Despite the efforts and proposals that have been developed within the legal and executive framework, important gaps related to economic, geographic and cultural factors still persist and obstruct access to mental health services.8

The DIADA (Detection and Integrated Care for Depression and Alcohol Use in Primary Care) project is a systematic, multicentric investigation and implementation project that implements a new model of care for mental health in Colombia. DIADA’s main objective is to integrate mental health into primary care through a collaborative model, including mobile technology and personnel training, to support the screening, diagnosis and treatment of depression and harmful alcohol use. The project executed a pilot phase in a single primary urban care site located in Bogotá with subsequent implementation to six other, rural and urban, primary care sites in various Colombian communities.9

Other low and middle income countries have implemented strategies promoting the integration of mental health in primary care and stigma is commonly identified as a barrier to achieve this.3,4 Thus, it is important to analyze the stigma towards mental health and its role in the early implementation stage of projects such as DIADA.

Moreover, it is important to note that, in Colombia, alcohol is used for recreational, social, ritualistic and even religious purposes; it is consumed not only in moments of leisure and celebration but also when faced with pain, sadness and anguish.10 Like in much of rest of the world, alcohol consumption is a socially accepted practice,10,11 meaning that, the acceptance of alcohol consumption is not something exclusively unique to Colombian culture; but it is an aspect that could affect the perception of the stigma towards mental health, when addressing disorders linked to alcohol use.

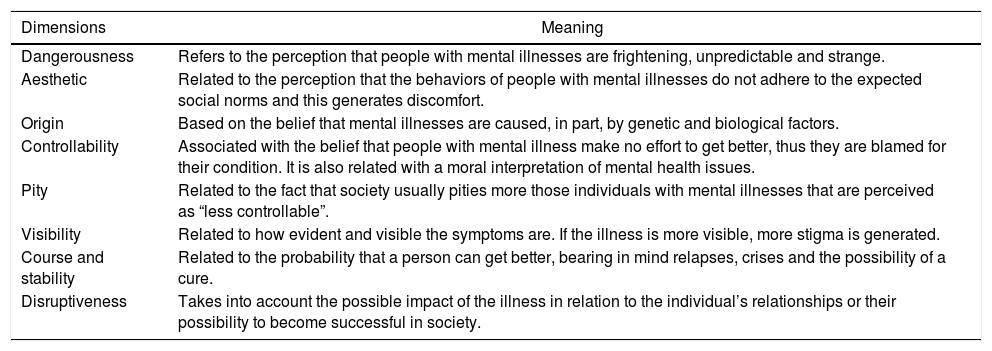

Theoretical frameworkIn his book titled “Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity”, Erving Goffman defines stigma as a “profoundly discrediting attribute” that prompts a change in perception of the stigmatized individual. A stigmatized individual is initially a “complete and normal person” but, due to stigma, becomes a “contaminated and unworthy” individual.12 Stigma places the individual in a condition of inferiority and loss of status, which in turn generates feelings of shame, guilt and humiliation.13 Additionally, stigma has various dimensions which facilitate the existence and maintenance of stigma as well as social rejection towards affected individuals.14 The dimensions of stigma applied to mental health in this study14 are found in Table 1.

Dimensions of stigma and their meanings.14

| Dimensions | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Dangerousness | Refers to the perception that people with mental illnesses are frightening, unpredictable and strange. |

| Aesthetic | Related to the perception that the behaviors of people with mental illnesses do not adhere to the expected social norms and this generates discomfort. |

| Origin | Based on the belief that mental illnesses are caused, in part, by genetic and biological factors. |

| Controllability | Associated with the belief that people with mental illness make no effort to get better, thus they are blamed for their condition. It is also related with a moral interpretation of mental health issues. |

| Pity | Related to the fact that society usually pities more those individuals with mental illnesses that are perceived as “less controllable”. |

| Visibility | Related to how evident and visible the symptoms are. If the illness is more visible, more stigma is generated. |

| Course and stability | Related to the probability that a person can get better, bearing in mind relapses, crises and the possibility of a cure. |

| Disruptiveness | Takes into account the possible impact of the illness in relation to the individual’s relationships or their possibility to become successful in society. |

Stigma can also be described on social dimensions, including social stigma, which is executed by the general population, and self-stigma, which is executed by the same individual who has internalized a perceived social stigma.14,15 Thus, the sources of stigma are diverse.

Stigma deprives people of their dignity and interferes with their participation in society.16 It is common for people who suffer from mental illnesses to experience stigma within the health care system,17 not only on a personal level but also due to the limited attention paid to mental health within healthcare by executive and legislative stakeholders (who are responsible for the development and infrastructure directed towards the improvement of the healthcare system).18 Stigma not only exacerbates the experience of a mental illness in those who have it, due to the fact that it compromises the individual’s quality of life,15 but also hinders people who could benefit from medical attention from seeking early treatment.12

Consequently, stigma is conceived as an important sociocultural barrier that impedes people who would meet criteria for a mental illness diagnosis in accessing mental health services and deprives them of the possibility of receiving critical and comprehensive healthcare for their mental health condition.18

Materials and methodsThe protocol for this study was approved by the institutional review boards of Dartmouth College in the U.S. and Pontificia Javeriana University in Colombia. Twenty-four semi-structured individual interviews with eighteen stakeholders were conducted during the early stage of implementation of the DIADA model of mental health care in partnering primary care systems. The stakeholders included administrative personnel, physicians and patients directly involved in the project. Stakeholders signed a consent form explaining the purpose of the interview and ensuring that the use and storage of the data collected would be confidential and used exclusively by the DIADA research group. The stakeholders also gave verbal consent at the moment prior to the interview further confirming their written consent. The semi-structured interviews were conducted based on 3 interview guides, tailored for each stakeholder group, developed by the team to explore the perceptions, aptitudes, attitudes, practices and experiences of the stakeholders with relation to the access, continuity, integration, quality and problem solving capacity regarding mental health since the implementation of the DIADA project.9 Interviews were conducted with all stakeholders at three months post-implementation of the DIADA model of care, and a subset of these stakeholders (3 physicians and 3 administrative personnel) were interviewed a second time at 6 months post-implementation. All interviews were transcribed from the original audio to a Word format and then all the transcriptions were de-identified and stored in a file on a secure computer.

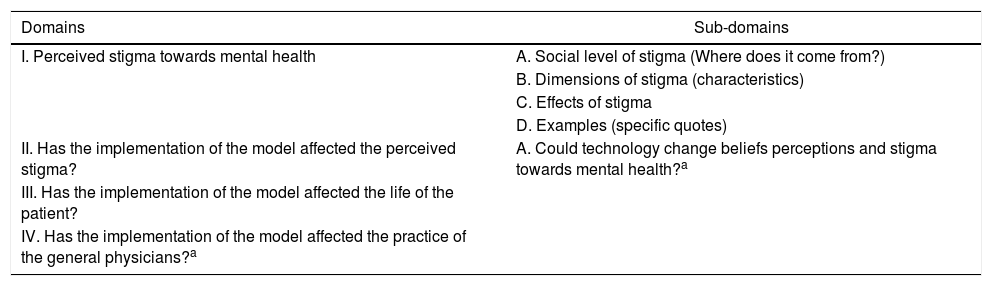

The data were analyzed using a “rapid analysis” technique. Rapid analysis is a technique used to reduce and organize data and is based on the systematic application of text analysis formats with neutral domains in order to organize information in matrices and facilitate the analysis of the content.19 Based on the interview guides, a text analysis format was developed in Word for each of the stakeholder groups. The three text analysis formats included: four domains for patients and three domains for physicians and administrative personnel, four sub-domains for all of the stakeholders and an additional subdomain for the physicians and the administrative personnel. The domains and subdomains used were neutral and specific and can be found in Table 2.

Domains used in the text analysis formats.

| Domains | Sub-domains |

|---|---|

| I. Perceived stigma towards mental health | A. Social level of stigma (Where does it come from?) |

| B. Dimensions of stigma (characteristics) | |

| C. Effects of stigma | |

| D. Examples (specific quotes) | |

| II. Has the implementation of the model affected the perceived stigma? | A. Could technology change beliefs perceptions and stigma towards mental health?a |

| III. Has the implementation of the model affected the life of the patient? | |

| IV. Has the implementation of the model affected the practice of the general physicians?a |

The text analysis formats were applied in a systematic way: starting with the reading of each transcription and then filling out the text analysis format accordingly for each one of the interviews. The data collected in the text analysis formats was then moved to 3 different matrices, one for each stakeholder group using Excel and then was abridged using abbreviations for the aspects frequently identified. The interview transcripts and text analysis formats were developed, analyzed and abridged by a single researcher. This researcher is a Colombian woman who is a general physician.

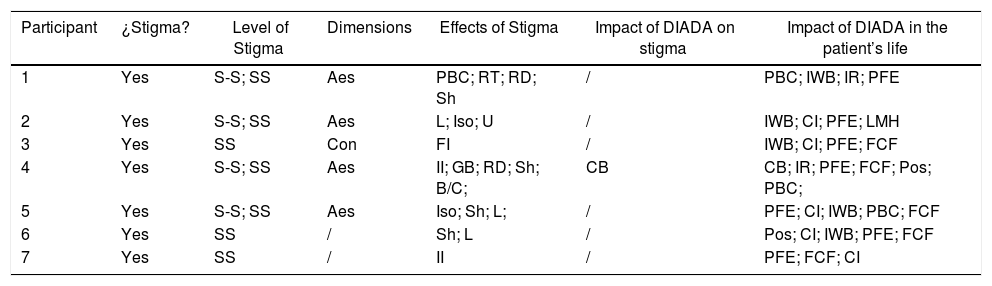

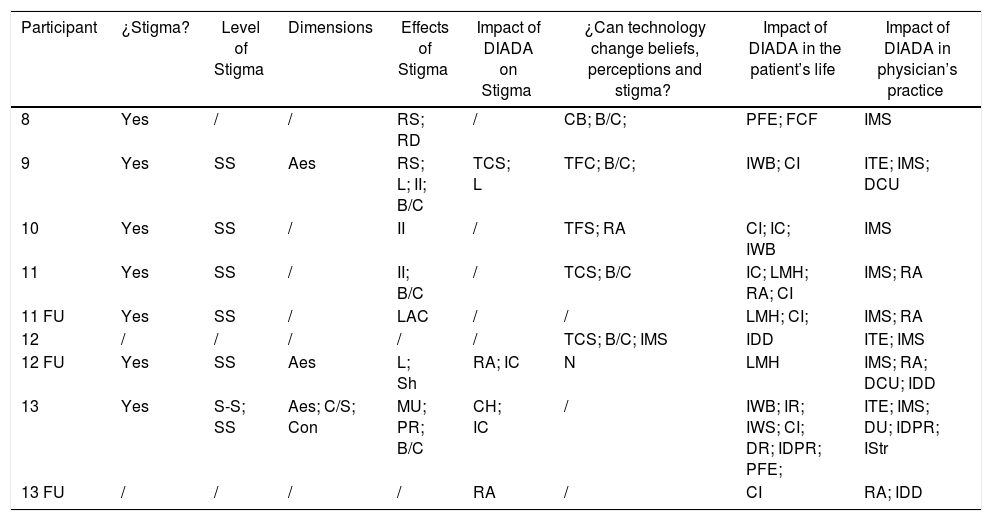

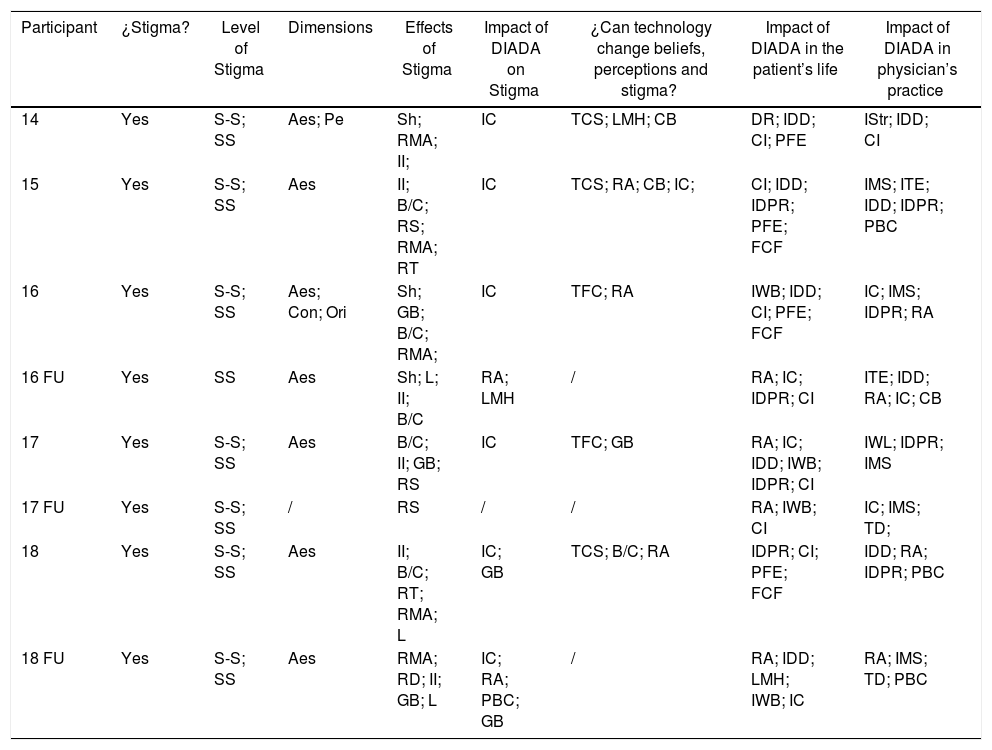

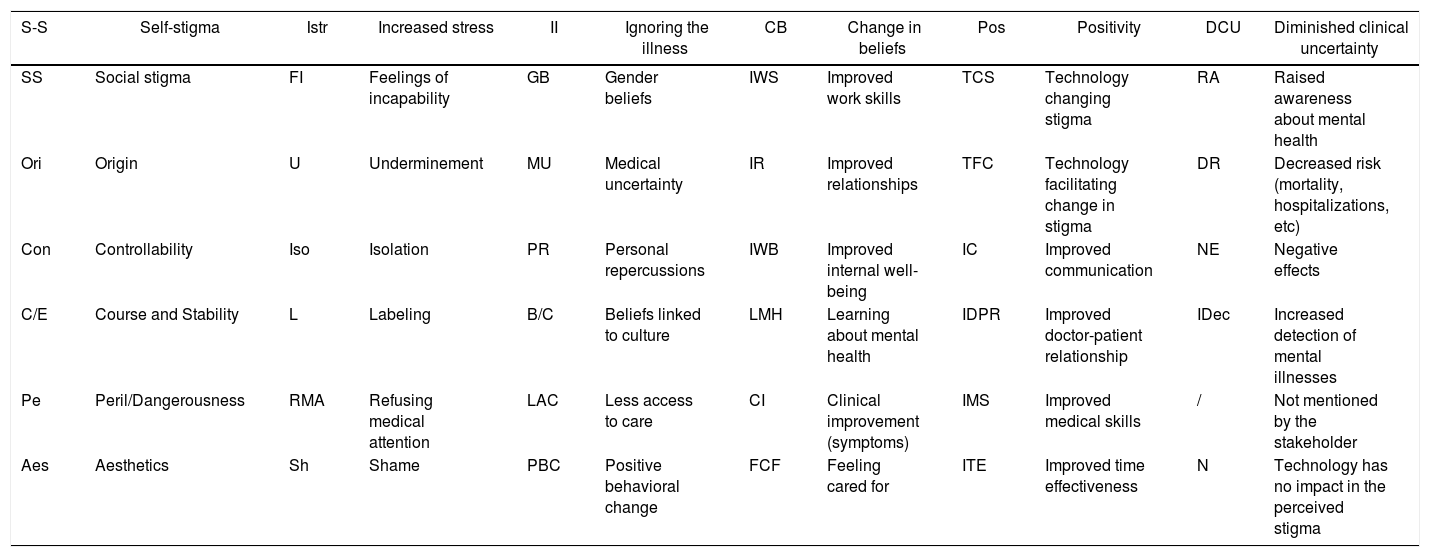

ResultsThe results of the analysis of the interviews can be found in the following tables: Table 3 shows the results for the patient group, Table 4 shows the results for the administrative personnel group and Table 5 shows the results for the physician group. The legend with the respective conventions is found in Table 6.

Patient stakeholder group results.

| Participant | ¿Stigma? | Level of Stigma | Dimensions | Effects of Stigma | Impact of DIADA on stigma | Impact of DIADA in the patient’s life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | S-S; SS | Aes | PBC; RT; RD; Sh | / | PBC; IWB; IR; PFE |

| 2 | Yes | S-S; SS | Aes | L; Iso; U | / | IWB; CI; PFE; LMH |

| 3 | Yes | SS | Con | FI | / | IWB; CI; PFE; FCF |

| 4 | Yes | S-S; SS | Aes | II; GB; RD; Sh; B/C; | CB | CB; IR; PFE; FCF; Pos; PBC; |

| 5 | Yes | S-S; SS | Aes | Iso; Sh; L; | / | PFE; CI; IWB; PBC; FCF |

| 6 | Yes | SS | / | Sh; L | / | Pos; CI; IWB; PFE; FCF |

| 7 | Yes | SS | / | II | / | PFE; FCF; CI |

Administrative personnel stakeholder group results.

| Participant | ¿Stigma? | Level of Stigma | Dimensions | Effects of Stigma | Impact of DIADA on Stigma | ¿Can technology change beliefs, perceptions and stigma? | Impact of DIADA in the patient’s life | Impact of DIADA in physician’s practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | Yes | / | / | RS; RD | / | CB; B/C; | PFE; FCF | IMS |

| 9 | Yes | SS | Aes | RS; L; II; B/C | TCS; L | TFC; B/C; | IWB; CI | ITE; IMS; DCU |

| 10 | Yes | SS | / | II | / | TFS; RA | CI; IC; IWB | IMS |

| 11 | Yes | SS | / | II; B/C | / | TCS; B/C | IC; LMH; RA; CI | IMS; RA |

| 11 FU | Yes | SS | / | LAC | / | / | LMH; CI; | IMS; RA |

| 12 | / | / | / | / | / | TCS; B/C; IMS | IDD | ITE; IMS |

| 12 FU | Yes | SS | Aes | L; Sh | RA; IC | N | LMH | IMS; RA; DCU; IDD |

| 13 | Yes | S-S; SS | Aes; C/S; Con | MU; PR; B/C | CH; IC | / | IWB; IR; IWS; CI; DR; IDPR; PFE; | ITE; IMS; DU; IDPR; IStr |

| 13 FU | / | / | / | / | RA | / | CI | RA; IDD |

Physician stakeholder group results.

| Participant | ¿Stigma? | Level of Stigma | Dimensions | Effects of Stigma | Impact of DIADA on Stigma | ¿Can technology change beliefs, perceptions and stigma? | Impact of DIADA in the patient’s life | Impact of DIADA in physician’s practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | Yes | S-S; SS | Aes; Pe | Sh; RMA; II; | IC | TCS; LMH; CB | DR; IDD; CI; PFE | IStr; IDD; CI |

| 15 | Yes | S-S; SS | Aes | II; B/C; RS; RMA; RT | IC | TCS; RA; CB; IC; | CI; IDD; IDPR; PFE; FCF | IMS; ITE; IDD; IDPR; PBC |

| 16 | Yes | S-S; SS | Aes; Con; Ori | Sh; GB; B/C; RMA; | IC | TFC; RA | IWB; IDD; CI; PFE; FCF | IC; IMS; IDPR; RA |

| 16 FU | Yes | SS | Aes | Sh; L; II; B/C | RA; LMH | / | RA; IC; IDPR; CI | ITE; IDD; RA; IC; CB |

| 17 | Yes | S-S; SS | Aes | B/C; II; GB; RS | IC | TFC; GB | RA; IC; IDD; IWB; IDPR; CI | IWL; IDPR; IMS |

| 17 FU | Yes | S-S; SS | / | RS | / | / | RA; IWB; CI | IC; IMS; TD; |

| 18 | Yes | S-S; SS | Aes | II; B/C; RT; RMA; L | IC; GB | TCS; B/C; RA | IDPR; CI; PFE; FCF | IDD; RA; IDPR; PBC |

| 18 FU | Yes | S-S; SS | Aes | RMA; RD; II; GB; L | IC; RA; PBC; GB | / | RA; IDD; LMH; IWB; IC | RA; IMS; TD; PBC |

Legend.

| S-S | Self-stigma | Istr | Increased stress | II | Ignoring the illness | CB | Change in beliefs | Pos | Positivity | DCU | Diminished clinical uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | Social stigma | FI | Feelings of incapability | GB | Gender beliefs | IWS | Improved work skills | TCS | Technology changing stigma | RA | Raised awareness about mental health |

| Ori | Origin | U | Underminement | MU | Medical uncertainty | IR | Improved relationships | TFC | Technology facilitating change in stigma | DR | Decreased risk (mortality, hospitalizations, etc) |

| Con | Controllability | Iso | Isolation | PR | Personal repercussions | IWB | Improved internal well-being | IC | Improved communication | NE | Negative effects |

| C/E | Course and Stability | L | Labeling | B/C | Beliefs linked to culture | LMH | Learning about mental health | IDPR | Improved doctor-patient relationship | IDec | Increased detection of mental illnesses |

| Pe | Peril/Dangerousness | RMA | Refusing medical attention | LAC | Less access to care | CI | Clinical improvement (symptoms) | IMS | Improved medical skills | / | Not mentioned by the stakeholder |

| Aes | Aesthetics | Sh | Shame | PBC | Positive behavioral change | FCF | Feeling cared for | ITE | Improved time effectiveness | N | Technology has no impact in the perceived stigma |

All stakeholders (N = 18/18) mentioned the presence of stigma towards mental health, with particular emphasis on social stigma. Twelve stakeholders referenced the aesthetic dimension of stigma. Of the effects of stigma, ignoring the illness was mentioned by ten stakeholders, refusing medical attention for mental health was mentioned by nine stakeholders, and shame and labeling were both mentioned by seven stakeholders. “…My family thinks I am crazy, meaning that they also have suggested it, so I have no one to talk to…”

-Stakeholder (patient) “…and a lot of times the patient feels shame, or don’t want to consult, or believe that consulting for depression means he/she is crazy so he/she doesn’t like it, or they don’t know how to consult or how to manage the situation…”

-Stakeholder (physician)

Eight stakeholders related stigma with beliefs linked to culture, especially risky alcohol use, and four stakeholders related stigma with gender role beliefs. As a part of the gender role beliefs, we identified that the concept of “machismo” was alluded to frequently. “We celebrate everything with alcohol. Then, since it is a part of our normal life, and of our culture, one could say that we do not see it as a problem until something really bad happens…”

-Stakeholder (physician) “… it is very uncommon for one to tell somebody else that one is depressed or that one is bored with life. One does not share that. Then, like they say, one swallows it. As a man, one is not capable of doing it.”

-Stakeholder (patient) “…it is possible that they (men) are depressed and they don’t show it to society because it is weakness, in all the machismo issue: that men don’t cry, don’t get depressed, the man is strong, thus it may be that they are depressed but they refuse to express it because socially a man that gets depressed and cries is bad…”

-Stakeholder (physician)

Impact of DIADA on stigmaTen stakeholders noted that the DIADA project had an impact on stigma and related the impact mainly to the improvement of communication and an increased awareness about mental illness. “There are patients that are very reticent, like very timid when it is time to speak about their emotional problems, so, I have seen that with the screening they open up more and they are able to talk openly about thing during the consult that they would never mention before.”

-Stakeholder (physician) “I truly think that one of the main advantages has been the sensibility of the professionals or of all physicians when faced with mental health problems.”

-Stakeholder (administrative personnel)

“Could technology change beliefs perceptions and stigma towards mental health?”With respect to this question, which was directed only to the physicians and administrative personnel (N = 11/18), seven stakeholders mentioned that technology facilitates change towards reducing stigma. Comments about how technology may impact stigma were frequent in relation to some changes in beliefs linked to culture and with the increase of awareness towards mental health. Three stakeholders affirmed that technology can change stigma. One stakeholder indicated that technology has no impact on stigma. “Technology can support the improvement or the making of a social change, but technology alone will not allow you to make that social change: allowing you to remove taboos or stigmas that in a given moment are not “normal”… Let’s say that in order to make that change, of something cultural that is also very ingrained in our culture, because, in the case of alcoholism, which is socially accepted, I think there have to be a lot of more components and not just the technological component.”

-Stakeholder (administrative personnel)

The impact of DIADA in the life of the patientsAll the stakeholders (N = 18/18) frequently mentioned clinical improvement, improvement of the internal wellbeing of patients and patients feeling cared for. Additionally, there were references towards increased communication, improvement of the doctor-patient relationship, increased awareness towards mental health and learning about mental health. “… I feel that I belong to something that can become essential or important for society. Second, although I have not used the application, I feel that I have reduced my alcohol consumption…I think it has been positive, I have liked it, I liked that they are attentive towards me and that there is communication… It is not every day that somebody calls you to ask how you are and what have you been up to these days…”

-Stakeholder (patient) “Look, answering that is relaxing. These questions they ask us, especially the last one the one that says “if you have had attempts or yearning to commit suicide”, that is where one realizes that life is pretty and that one has never had those thoughts. One has to go on.”

-Stakeholder (patient)

The impact of DIADA in physician practiceThe physician and administrative personnel group (N = 11/18) emphasized improved medical skills related to mental health, increase in efficiency in consultation regarding mental health, increase in detection of mental illness, increase in awareness towards mental health and improvement of the doctor-patient relationship. Only three stakeholders mentioned negative effects, mainly pertaining to technical connectivity issues when using the digital screening tool or diagnostic confirmation tool and increase in stress among physician personnel. “…I think that the gain we have had is acquiring a little bit more of sensibility and to really start to ask ourselves a little and actually worry about “what is this patient feeling?”

-Stakeholder (physician) “…let’s say that in this process one adapts the attention of one’s practice, so now you have pharmacological and non-pharmacological tools for the patient and I, for example, think losing the fear of giving medicine to a patient is very interesting…”

-Stakeholder (physician) “So, I think this could also improve the doctor-patient relationship in the sense that the patients would feel like “Ok, you are worried not only for my knee, but also you are asking me if I am depressed, if I sleep alright, if I concentrate.”

-Stakeholder (physician)

DiscussionStigma, commonly understood under a socio-cognitive framework,14 comprises a process that includes stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination.20 Stereotypes allow people to be categorized in social groups, generating expectations on how an individual’s behavior should be as a member of a specific group.20 In the case of persons with mental illness, pre-existing prejudice also creates, not only negative stereotypes, but also negative reactions towards this population.20,21 Discrimination, evasion and exclusion are examples of these reactions.21,22 In this study, stigma towards mental health was perceived by all stakeholders, highlighting its importance in the diagnostic and therapeutic process for mental illness.

The fact that social stigma was perceived more frequently than self-stigma, even if there is an important overlap with the perception of both, is important. This overlap suggests that the effects of stigma are not caused by the dynamics of social stigma alone, but that self-stigma also contributes to the internalization of stereotypes and prejudices by the same individuals.

We can relate the social level of stigma with the aesthetic dimension, given that the latter is derived from a discomfort generated in the general public when faced with individuals whose behaviors are outside of what is considered “normal”.14 This suggests that, within the population, there is a more accentuated preoccupation towards how others will perceive them than how they perceive themselves. Thus, it is not surprising that ignoring the illness and refusing medical attention are frequently mentioned as effects of stigma. Likewise, shame and labeling are effects that can be linked to aesthetics given that when one is stigmatized, the associated stereotype may support labeling and produces shame in that individual. This, added to the preexisting prejudices, may support discriminatory action.15,21

In the literature, shame is commonly conceived of as an effect linked to self-stigma15,21 considering that, when internalizing the stigma created by society, individuals have negative thoughts and emotional reactions that lead them to feel shame. As a consequence, individuals may avoid situations, in which originally, they were subject to external stigmatization because they now stigmatize themselves.15,21 Shame, more than just another consequence the individual lives through, is possibly an effect that is linked to other effects shown in the study, like ignoring the illness and refusing medical attention.

Impact of DIADA project on stigma towards mental healthChanging attitudes and behaviors that promote stigma towards mental health is a difficult process and various methods to decrease stigma have been studied.16 In a meta-analysis, Corrigan et al. conclude that educational methods that aim to correct myths and false beliefs towards mental illness and in-person contact with people that have mental illnesses are the most effective methods to diminish stigma in adults.23 In this study, stakeholders highlight that the DIADA project could have an impact on stigma, taking into account the increase in awareness of mental health and the improvement in communication regarding mental health issues.

Thus, as the population becomes more conscious about the importance of mental health and, in turn, perceives that mental illnesses are common, people who suffer from these pathologies, diagnosed or not, could feel more comfortable talking about them, whether it be with a professional, their family or social group. The aforementioned would not only facilitate the diagnosis of mental illnesses in Colombia, but also promote early treatment, and strengthen the doctor-patient relationship and the quality of life of those people who require mental health services.23

Likewise, it is important to highlight that stigma towards mental health is not the only barrier that limits access to mental health services; in our context, financial and structural barriers (geographical location, etc.), and lack of knowledge in terms of health care routes obstruct access and adherence to treatment.5 The DIADA project proposes to overcome some of these barriers, taking into account that the model facilitates access to mental health services for many users and, by doing so, stigma is also ideally impacted. Resolving other access barriers may also be a way to tackle problematic stigma towards mental health.

Concerning the impact of technology over beliefs, perceptions and stigma towards mental healthAlthough some physician and the administrative personnel mentioned that technology has that power of change, the majority of stakeholders refer to technology as a facilitating agent for changing stigma with an important condition: the need for a cultural change. Additionally, some stakeholders mention that the change that technology solely provides is related to the increase of awareness in the population regarding the importance of mental health and mental illnesses.

Impact of DIADA project in the life of patients and in physician practiceAll stakeholders perceived that the DIADA project had a positive and varied impact in the life of patients: with frequent allusions to clinical improvement, increased patient internal wellbeing, decrease in alcohol consumption and depressive symptoms, positivity, etc. Also, patient stakeholders mentioned feeling supported and cared for by someone else, in relation to the clinical follow-up calls made to them during the study.

Physician and administrative stakeholders mentioned many positive aspects the DIADA project has brought to physician practice including improvement in clinical abilities in mental health issues, efficiency in mental health consultation with the mental health screening processes, increase in detection of mental illnesses, increase in awareness about mental health and improvement in doctor-patient relationship.

Taking this into account, the implementation of a model like the DIADA project could have multiple long-term benefits such as improving quality of life and illness course in patients with mental illness, facilitating diagnosis and both short- and long-term treatment, and strengthening the bond between patients and their physicians.

Cultural aspects of the Colombian context and stigmaWhen talking about stigma, culture, is an important aspect to keep in mind, given that it is a factor that molds stigma in society.24 In this realm, culture refers to the attributes, belief system and values shared by a population that influence its customs, norms, practices, social institutions, psychological processes and organizations.25 Thus, to understand the perceived stigma in this study, it is important to comprehend the cultural aspects from a Colombian point of view and, also, how the Colombian interacts with and characterizes stigma.

Beliefs about gender roles and “machismo”In this study, there were allusions to “machismo” and mentions of gender roles as cultural factors that play an important role in the perceived stigma. These beliefs may pose as a barrier, largely for men in particular, for communication, acceptance or recognition towards a mental health issue.

“Machismo”, according to the Spanish Royal Academy, is “a way of sexism or discrimination characterized by the prevalence of the male.”26 According to the Colombian anthropologist Mara Viveros Vihgoya, “machismo” can also be defined as “the male obsession with predominance and virility, which is expressed in the possession with respect to women themselves and in acts of aggression and boasting in relation to other men.”27 Therefore, taking into account that various stakeholders mention that men have more difficulties accepting mental illness diagnoses than women, it is important to understand the role “machismo” and socially established gender roles play in stigma towards mental health.

In Colombia, men are commonly expected to be strong and be the main financial providers of a home. A Peruvian exploratory gender study mentions that individuals with mental illness fear rejection by their close social circle because mental illness represents an incapacity to match the expectations they have according to their gender.28 By understanding “machismo” as a factor that molds the stigma in the Colombian context, we can see that facing a mental illness diagnosis suggests not only the presence of a flaw or weakness in the individual in question, but also obstacles that negatively affect their professional life.29 The social construct of the man as a strong being and the main financial provider shatters. This could explain the tendency in stakeholders to mention that men have more difficulties, not only in consulting for mental health issues, but in facing a diagnosis of a similar nature.

Beliefs related to cultureIn this study, some beliefs related to culture are mentioned, especially when talking about risky alcohol use and alcoholism. Ignoring the illness was frequently mentioned and, in this study, it is commonly linked to fear of being labeled as an “alcoholic” and to the erroneous perception that alcohol consumption, which is in some cases excessive, frequent and/or risky, is not harmful, given that alcohol consumption is socially accepted in the Colombian context.30

It is important to highlight that, in Colombia, especially in rural areas, daily alcohol consumption is common given that there are artisanal beverages (like “chicha”, “guarapo”, “chirrinchi”, “ñeque”, etc.) that are consumed daily. Alcohol use often starts at an early age, meaning that its use starts at around infancy and is predominant during the work day in the countryside.31

Taking this into account, we derive that for individuals who consume these types of beverages, understanding that they were introduced at an early age and are considered as a part of their day to day labor, facing a diagnosis of risky alcohol use could be problematic.

ConclusionsThe perceived stigma in this study appears to be mainly social and is predominantly linked to the aesthetic dimension of stigma and is very important to people. The stigma perceived by the stakeholders yields various effects, mainly: ignoring the illness, refusing medical attention, and shame and labeling, which in this case, act as barriers to accessing services for people who need mental health care. Taking into account that the perceived stigma towards mental health was noted so unanimously by the stakeholders, we conclude that further studies investigating stigma in detail would be of great impact for the public and mental health scope in the country.

The results suggest that the DIADA project had an impact in decreasing stigma given that, when facilitating access to healthcare services, awareness and communication about mental health was increased. It was unanimously perceived that the DIADA project had a positive impact in the lives of patients and in the medical practice of physicians.

The implementation of technologies and educational materials was perceived as a premise of change in the perceptions, beliefs and stigma regarding mental health at a sociocultural level, with the condition that they are accompanied by a cultural change. The cultural environment of the population studied is a key aspect to understanding how stigma is developed in the Colombian context. In this study, “machismo”, gender roles, acceptability of alcohol at a social level and its normalization are the cultural aspects most frequently linked towards the creation of stigma towards mental health. We consider that further analyses regarding these aspects is necessary to plan interventions that could help diminish stigma towards mental health that takes into account cultural factors.

Finally, we conclude that implementing a model of health care services where mental health is successfully integrated into primary care could bring significant benefits when addressing stigma and could also benefit, alongside purely cultural processes, the way in which mental health is perceived and managed in Colombia.

FundingThe investigation reported in this publication was financed by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) via Grant# 1U19MH109988 (Multiple Principal Investigators: Lisa A. Marsch, PhD and Carlos Gómez-Restrepo, MD PhD). The content of this article is only the opinion of the authors and does not reflect the viewpoints of the NIH or the Government of the United States of America.

Conflicts of interestAuthors report not having any conflicts of interest. Dr. Lisa A. Marsch, one of the principal investigators on this project, is affiliated with the business that developed the mobile intervention platform that is being used in this research. This relationship is extensively managed by Dr. Marsch and her academic institution.

The authors thank Sarah K Moore, PhD at Dartmouth College for her guidance in the theoretical framework and execution of the study.

Please cite this article as: Jassir Acosta MP, Cárdenas Charry MP, Uribe Restrepo JM, Cepeda M, Cubillos L, Bartels SM, et al. Caracterización del estigma percibido hacia la salud mental en la implementación de un modelo de servicios integrados en atención primaria en Colombia. Un análisis cualitativo. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:91–101.