Resident physicians who work more hours a day are prone to suffer mental health problems such as depression, a subject that has been little studied. In this regard, the aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms and to evaluate the association between the number of daily working hours and depressive symptoms in Peruvian residents.

MethodsAnalytical cross-sectional study that used the database of the National Survey for Resident Physicians-2016, a voluntary survey issued virtually by the National Council of Medical Residency of Peru to physicians who were undertaking their residency in Peru. The presence of depressive symptoms was considered as having obtained a score ≥3 with the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 scale. The number of hours worked each day was collected through a direct question. To assess the association of interest, prevalence ratios (PR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using crude and adjusted Poisson regressions with robust variance.

ResultsThe responses of 953 residents (41.3% women, mean age: 32.5 years) were evaluated, 14.6% of which presented depressive symptoms. In the adjusted analysis, it was found that the prevalence of depressive symptoms increased for each additional hour worked (PR = 1.11; 95% CI, 1.04–1.17).

ConclusionsOne in seven residents had depressive symptoms. For every extra daily working hour, the frequency of depressive symptoms increased by 11%.

Los médicos residentes que laboran más horas diarias son propensos a sufrir problemas de salud mental como la depresión, tema que se ha estudiado poco. Por ello, el presente estudio tiene por objetivos determinar la prevalencia de los síntomas depresivos y evaluar la asociación entre el número de horas diarias laboradas y la presencia de síntomas depresivos en residentes del Perú.

MétodosEstudio transversal analítico que usó la base de datos de la Encuesta Nacional para Médicos Residentes-2016, una encuesta voluntaria realizada virtualmente por el Consejo Nacional de Residentado Médico de Perú a médicos que realizaban su residencia en este país. Se consideró presencia de síntomas depresivos una puntuación ≥ 3 con la escala Patient Health Questionnaire-2. Las horas laboradas diariamente se tomaron mediante una pregunta directa. Para evaluar la asociación de interés, se calcularon razones de prevalencia (RP) y sus intervalos de confianza del 95% (IC95%) usando regresiones de Poisson brutas y ajustadas con varianza robusta.

ResultadosSe evaluaron las respuestas de 953 residentes (el 41,3% mujeres; media de edad, 32,5 años), de los que el 14,6% tenía síntomas depresivos. En el análisis ajustado, se encontró que la prevalencia de síntomas depresivos aumentaba por cada hora laborada adicional (RP = 1,11; IC95%, 1,04–1,17).

ConclusionesUno de cada 7 residentes presentó síntomas depresivos. Por cada hora laborada diariamente extra, la frecuencia de síntomas depresivos aumentó un 11%.

Due to their working and academic conditions, resident physicians may be particularly exposed to suffering mental health problems such as depression.1–4 In fact, a recent meta-analysis of 54 studies estimated a prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms in residents of 28.8%, although the results were highly heterogeneous.5 Depression in this population not only affects the lives of residents,6 it also has a negative impact on the quality of care they give to their patients, in addition to creating a greater risk of committing medical errors such as incorrect drug prescriptions.7,8

The residency stage for a specialist physician in training often demands many dedicated hours, meaning they have a higher workload and less time available for leisure, relaxation, seeking help and even sleep. All of this could affect the mental health of resident physicians.9 Nevertheless, previous reviews have found mixed results in terms of the impact of reducing the number of hours worked to under 80 hours per week in the United States (as recommended by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education [ACGME])8 on well-being or burnout among residents.10 Because of these mixed results, the Flexibility in Duty Hour Requirements for Surgical Training (FIRST) study11 is now underway in the United States. This is a pragmatic trial that seeks to assess whether the policy change on the number of hours of service of general surgery residency programmes affects variables relating to medical education and residents' well-being.

Moreover, few studies have looked at the association between the number of hours worked and symptoms of depression. One study conducted in 13 hospitals in the United States found a positive association between the number of hours worked and depression,4 while three studies that evaluated residents in surgery,2 internal medicine,12 and different specialties13 in the United States before and after implementing the ACGME hours limit did not find a significant reduction in the presence of depressive symptoms.

Latin America is a region characterised by low incomes for healthcare personnel,14 as well as a shortage of healthcare professionals and shortages of materials in its healthcare establishments.15 This could pose an additional risk for the mental health of resident physicians, in particular those who are exposed to these working conditions for a greater number of hours per week. However, few studies have assessed the prevalence of depressive symptoms in residents in Latin America,16–21 and no studies were found that looked at the association between hours worked and the presence of depressive symptoms in this region.

This study therefore aims to determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms and assess the association between the number of hours worked and depressive symptoms in residents in Peru.

Material and methodsStudy designThis is an analytical cross-sectional study. A secondary analysis was carried out of the Encuesta Nacional para Médicos Residentes 2016 [National Survey for Resident physicians 2016] (ENMERE-2016), conducted by the Comité Nacional del Residentado Médico del Perú [National Committee on the Medical Residency in Peru] (CONAREME). The methodology has been published in detail previously.22

Study population, sample and selection criteriaThe study population was made up of physicians pursuing a residency at any university in Peru during June 2016. For convenience, the sample included the residents who had taken part in the ENMERE-2016 survey. Those who did not provide information on the outcome or exposure of interest were excluded.

BackgroundPhysicians who wish to pursue a residency in Peru must apply for a place offered by any CONAREME-accredited university. Their admission will depend on a series of scores, including that obtained in a knowledge exam. For the year 2016, seven universities in Lima and sixteen in other cities in Peru were certified to offer medical residency programmes.23

Physicians who enrol in a residency programme choose the facility or hospital where they will work for the majority of their residency. These facilities are managed by the National Ministry of Health (MINSA), regional governments, the Ministry of Labour (Medical Social Security [EsSalud]), armed forces and police healthcare systems, or private entities.

ProceduresThe survey used in ENMERE-2016 was designed by CONAREME based on consultations with medical residents, consultations with specialists and researchers in medical education, and previous studies. This survey was evaluated by focus groups of medical residents and experts in medical educations, to ensure that it would be understood by participants and that the most relevant subjects linked to the problems of the Peruvian residency were addressed.

During June 2016, this survey was made available virtually to all residents in Peru through the official CONAREME website.23 CONAREME invited all residents in Peru to take part in the survey through emails, announcements on the official CONAREME Facebook page and in Peruvian periodicals.

The survey was voluntary. To access the survey, residents had to enter their identity document number and agree to voluntary participation. An email address was made available for survey-takers to ask any questions about the survey. The results were stored in the database on CONAREME's server.

For this analysis, permission to access the database, excluding participants' names and identity documents, was sought from CONAREME.

Outcome: depressive symptomsThe presence of depressive symptoms was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) scale,24 taking into account the modifications proposed by Calderón et al.25 for the questions in Peru. This scale includes two questions that ask about depressive symptoms over the last two weeks. Presence of depressive symptoms is defined as having obtained a score on this scale ≥3, which is used as a cut-off point due to its high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of major depressive disorder based on previous studies.26,27

Exposure: number of hours worked per dayThe number of hours worked per day was collected using the open question: “In the last month, on average, how many hours a day were you required to remain at your post in a normal day, not counting on-call shifts?”, which was evaluated quantitatively.

Other variablesOther variables available in the database, which were evaluated as potential confounders based on the literature consulted and the authors’ opinions, were: age, sex (male or female), marital status (single or married/cohabiting), city in Peru where the university through which the residency took place is located (Lima or provincial), institution to which the hospital facility where the residency took place belongs (MINSA, EsSalud or other), year of residency (first year, second year, or third year and beyond) and specialty pursued (medical, surgical or other). The specialty was categorised as “medical” if it related to preventive, diagnostic or therapeutic activities, “surgical” is it was related to surgical procedures, and “other” which brought together responses related to diagnostic support, management and other areas not included in the above categories.

Other areas assessed were satisfaction with the teaching received during the residency (satisfied or unsatisfied), whether at any time during the residency the resident suffered violence of any type (physical violence, sexual assault, verbal abuse or threats), average number of on-call shifts in the last month, including days and nights (0 or <5, 5–10, or >10), and time released from night on-call shifts (9:00 a.m. or earlier, 9:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m., or later than 2:00 p.m.).

Statistical methodsThe results were analysed using the STATA v.14.0 program. Mean ± standard deviation and absolute and relative frequencies were used for the descriptive results.

The evaluate the factors associated with the presence of depressive symptoms, unadjusted and adjusted Poisson regression analyses with robust variance were used to calculate prevalence ratios (PR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), with a p value <0.05 considered significant. The adjusted model included variables that obtained p < 0.20 in the unadjusted models.

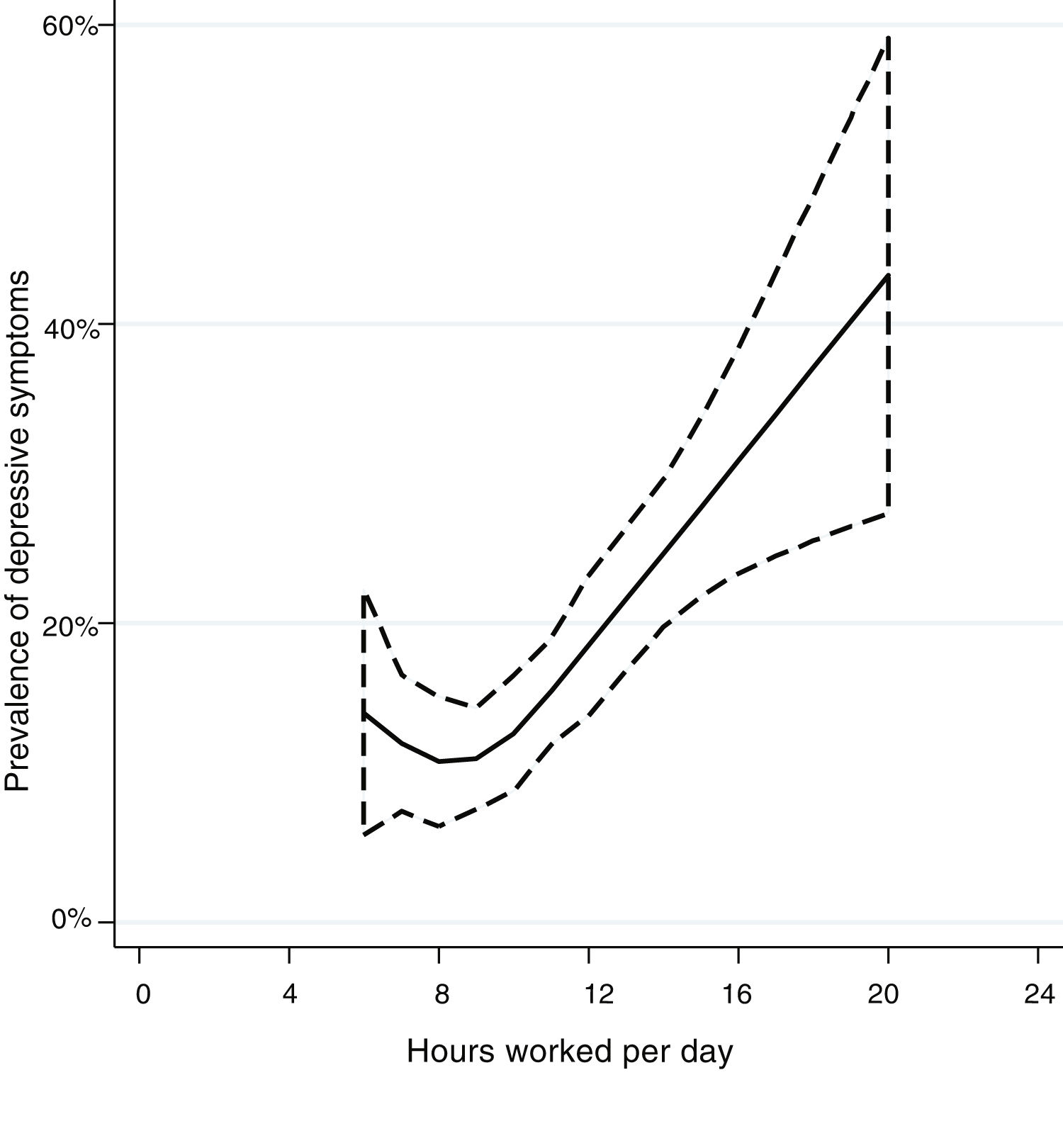

The association of interest was also represented graphically using restricted cubic splines with five knots obtained by default, as other authors have proposed.28

Ethical aspectsThis secondary analysis was reviewed by the ethics committee of Hospital San Bartolomé [San Bartolomé Hospital], Lima, Peru. There were no variables that might allow the residents to be identified.

ResultsGeneral dataIn June 2016, there were 7,393 physicians pursuing their residency in Peru according to the CONAREME database. Of these, 1,163 (15.7%) visited the virtual platform for the survey and answered at least the first question, but only 953 (12.9%) answered all PHQ-2 questions on working and were therefore included in this study's analysis.

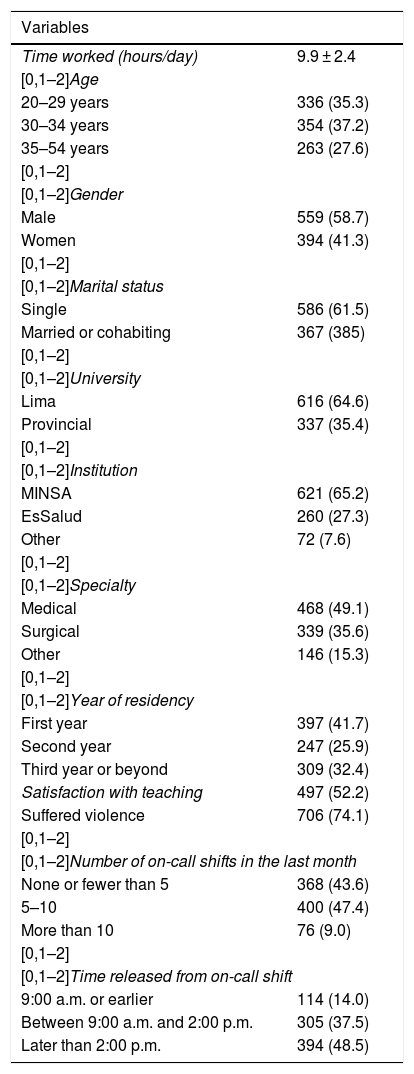

Of the subjects included, the mean age was 32.5 ± 5.4; 394 (41.3%) were women, 367 (38.5%) were married or cohabiting, 616 (64.6%) were pursuing their residency through a university in Lima, 621 (65.2%) were doing so in a MINSA hospital, 397 (41.7%) were in their first years and 468 (49.1%) were pursuing a medical residency. In addition, 497 (52.2%) felt satisfied with the teaching at their hospital facility, 400 (47.4%) had been on 5–10 on-call shifts in the last month, 305 (37.5%) were released from on-call shifts between 9:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. and 394 (48.5%) after 2:00 p.m. (Table 1).

Description of the population studied.

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Time worked (hours/day) | 9.9 ± 2.4 |

| [0,1–2]Age | |

| 20–29 years | 336 (35.3) |

| 30–34 years | 354 (37.2) |

| 35–54 years | 263 (27.6) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Gender | |

| Male | 559 (58.7) |

| Women | 394 (41.3) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Marital status | |

| Single | 586 (61.5) |

| Married or cohabiting | 367 (385) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]University | |

| Lima | 616 (64.6) |

| Provincial | 337 (35.4) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Institution | |

| MINSA | 621 (65.2) |

| EsSalud | 260 (27.3) |

| Other | 72 (7.6) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Specialty | |

| Medical | 468 (49.1) |

| Surgical | 339 (35.6) |

| Other | 146 (15.3) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Year of residency | |

| First year | 397 (41.7) |

| Second year | 247 (25.9) |

| Third year or beyond | 309 (32.4) |

| Satisfaction with teaching | 497 (52.2) |

| Suffered violence | 706 (74.1) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Number of on-call shifts in the last month | |

| None or fewer than 5 | 368 (43.6) |

| 5–10 | 400 (47.4) |

| More than 10 | 76 (9.0) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Time released from on-call shift | |

| 9:00 a.m. or earlier | 114 (14.0) |

| Between 9:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. | 305 (37.5) |

| Later than 2:00 p.m. | 394 (48.5) |

Values are expressed as or mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

According to the PHQ-2, 139 (14.6%) presented depressive symptoms, defined by a score ≥3. The mean hours worked per day were 9.9 ± 2.4.

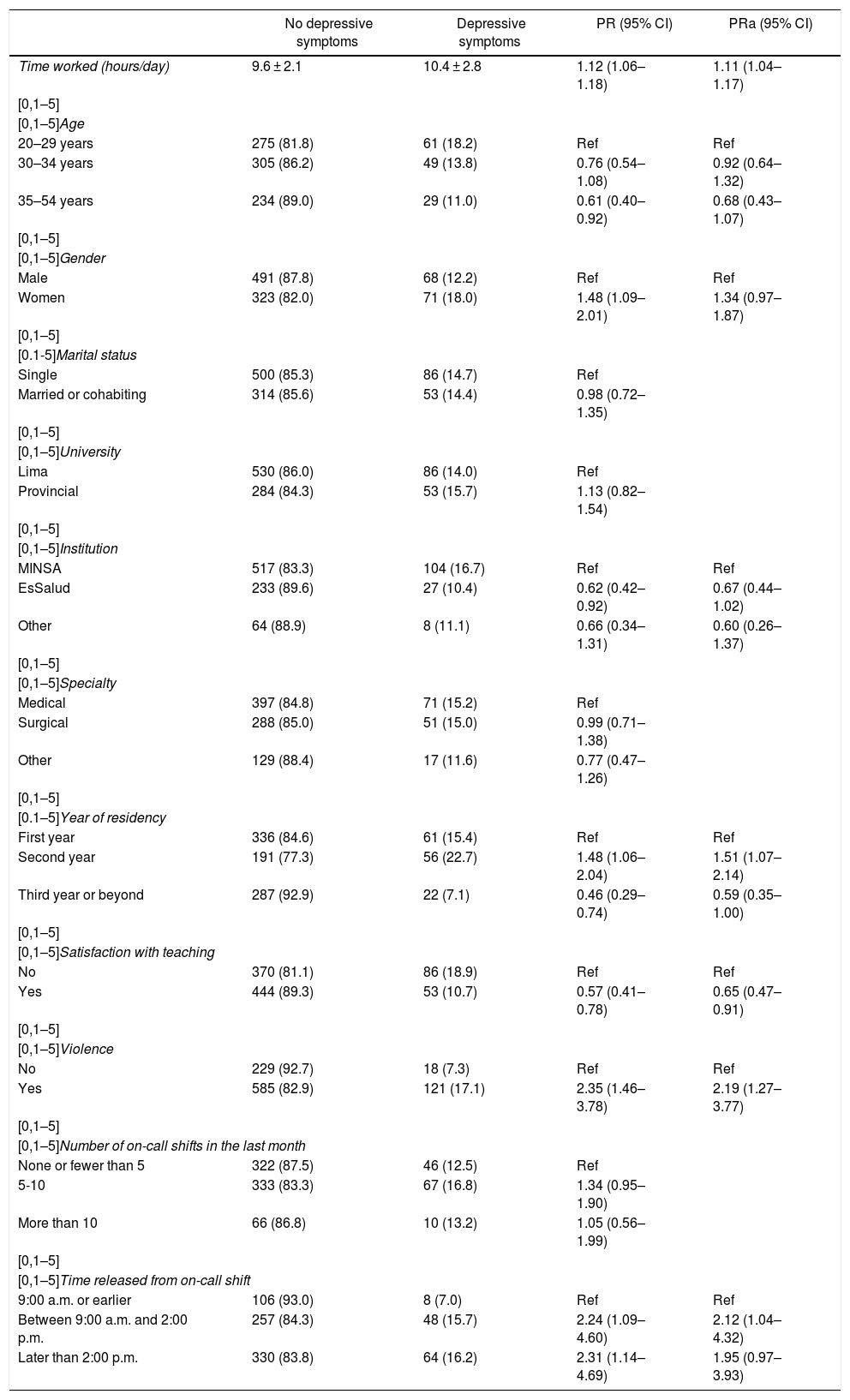

Hours worked per day associated with depressive symptomsIn the unadjusted model, it was found that, for each additional hours worked, the prevalence of depressive symptoms saw a significant increase (PR = 1.12; 95% CI 1.06–1.18). The same was also observed when adjusting for other co-variables (PR = 1.11; 95% CI 1.04–1.17) (Table 2). The graphical representation of this association shows that the prevalence of depressive symptoms was relatively constant among those working between six and nine hours per day, but that there was a marked linear association among those working nine or more hours per day (Fig. 1).

Factors associated with depressive symptoms.

| No depressive symptoms | Depressive symptoms | PR (95% CI) | PRa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time worked (hours/day) | 9.6 ± 2.1 | 10.4 ± 2.8 | 1.12 (1.06–1.18) | 1.11 (1.04–1.17) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Age | ||||

| 20–29 years | 275 (81.8) | 61 (18.2) | Ref | Ref |

| 30–34 years | 305 (86.2) | 49 (13.8) | 0.76 (0.54–1.08) | 0.92 (0.64–1.32) |

| 35–54 years | 234 (89.0) | 29 (11.0) | 0.61 (0.40–0.92) | 0.68 (0.43–1.07) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Gender | ||||

| Male | 491 (87.8) | 68 (12.2) | Ref | Ref |

| Women | 323 (82.0) | 71 (18.0) | 1.48 (1.09–2.01) | 1.34 (0.97–1.87) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0.1-5]Marital status | ||||

| Single | 500 (85.3) | 86 (14.7) | Ref | |

| Married or cohabiting | 314 (85.6) | 53 (14.4) | 0.98 (0.72–1.35) | |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]University | ||||

| Lima | 530 (86.0) | 86 (14.0) | Ref | |

| Provincial | 284 (84.3) | 53 (15.7) | 1.13 (0.82–1.54) | |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Institution | ||||

| MINSA | 517 (83.3) | 104 (16.7) | Ref | Ref |

| EsSalud | 233 (89.6) | 27 (10.4) | 0.62 (0.42–0.92) | 0.67 (0.44–1.02) |

| Other | 64 (88.9) | 8 (11.1) | 0.66 (0.34–1.31) | 0.60 (0.26–1.37) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Specialty | ||||

| Medical | 397 (84.8) | 71 (15.2) | Ref | |

| Surgical | 288 (85.0) | 51 (15.0) | 0.99 (0.71–1.38) | |

| Other | 129 (88.4) | 17 (11.6) | 0.77 (0.47–1.26) | |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0.1–5]Year of residency | ||||

| First year | 336 (84.6) | 61 (15.4) | Ref | Ref |

| Second year | 191 (77.3) | 56 (22.7) | 1.48 (1.06–2.04) | 1.51 (1.07–2.14) |

| Third year or beyond | 287 (92.9) | 22 (7.1) | 0.46 (0.29–0.74) | 0.59 (0.35–1.00) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Satisfaction with teaching | ||||

| No | 370 (81.1) | 86 (18.9) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 444 (89.3) | 53 (10.7) | 0.57 (0.41–0.78) | 0.65 (0.47–0.91) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Violence | ||||

| No | 229 (92.7) | 18 (7.3) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 585 (82.9) | 121 (17.1) | 2.35 (1.46–3.78) | 2.19 (1.27–3.77) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Number of on-call shifts in the last month | ||||

| None or fewer than 5 | 322 (87.5) | 46 (12.5) | Ref | |

| 5-10 | 333 (83.3) | 67 (16.8) | 1.34 (0.95–1.90) | |

| More than 10 | 66 (86.8) | 10 (13.2) | 1.05 (0.56–1.99) | |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Time released from on-call shift | ||||

| 9:00 a.m. or earlier | 106 (93.0) | 8 (7.0) | Ref | Ref |

| Between 9:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. | 257 (84.3) | 48 (15.7) | 2.24 (1.09–4.60) | 2.12 (1.04–4.32) |

| Later than 2:00 p.m. | 330 (83.8) | 64 (16.2) | 2.31 (1.14–4.69) | 1.95 (0.97–3.93) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; PR: prevalence ratio.

Values are expressed as or mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

The adjusted model revealed a significant association between the presence of depressive symptoms and being in the second (PR = 1.51; 95% CI 1.07–2.14) or third year of a residency (PR = 0.59; 95% CI 0.35-1.00), feeling satisfied with the teaching at a hospital facility (PR = 0.65; 95% CI 0.47–0.91), having suffered violence during the residency (PR = 2.19; 95% CI 1.27–3.77) and being released from on-call shifts between 9:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. (PR = 2.12; 95% CI 1.04–4.32) (Table 2).

DiscussionPrevalence of depressive symptomsSome 14.6% of the residents evaluated presented depressive symptoms, defined as a PHQ-2 ≥ 3 points. Only one previous study was found that used this instrument in resident physicians with a cut-off point of ≥3, which reported a 15.1% prevalence of PHQ-2 ≥ 3 in residents at New York University (United States),29 a similar figure to this study.

These results are also comparable to those of other studies conducted in resident physicians with different instruments; indeed, a systematic review of 54 studies found a mean prevalence of 28.8%, although estimates varied between 22.4% and 43.7%.5 In Peru, a previous study in 84 residents at Hospital Nacional Cayetano Heredia [Cayetano Heredia National Hospital] using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale found a prevalence of 38.6%.30 Another study conducted in 39 resident physicians at Hospital Daniel Alcides Carrión [Daniel Alcides Carrión Hospital] and using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale reported a prevalence of 13.3%.31 Unfortunately, the lack of uniformity in the instruments used means that an adequate comparison between these results and ours is not possible.

Association between hours worked and depressive symptomsOur study found and almost linear association between hours worked and the prevalence of depressive symptoms. Although one previous study had also found this association in residents at 13 hospitals in the United States,4 various studies that followed residents before and after the implementation of the ACGME hours limit in the United States did not find a significant reduction in the presence of depressive symptoms.2,12,13 This could be because the ACGME provisions only achieved a small reduction in working hours of between 0.4 and 3 h per day in the studies analysed.

The association between hours worked ad depressive symptoms found in this study highlights the importance of regulating working hours for resident physicians. In this respect, Peruvian legislation up to 2016 established that a resident's workload should not exceed 70 h per week excluding on-call shifts.32 Nevertheless, new regulations published in 2017 reduces this time to 60 h excluding on-call shifts (approximately 8.6 h per day).33 In spite of this, 68.2% of the population evaluated in this study indicated working 9 h per day or more. There is therefore a need to regularly assess compliance with current legislation for the medical residency programme in Peru, which could be achieved through oversight of facilities where residents work and anonymous surveys.

On the other hand, it is important to implement strategies for the early detection and treatment of cases of depression during the medical residency, such as periodic risk assessments and preventive and therapeutic programmes for resident physicians.34

Other factors found to be associatedThose in the second and third years of their residency presented a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than first-year residents. This may be explained by a cumulative phenomenon or physical and mental exhaustion.

Dissatisfaction with teaching was associated with the presence of depressive symptoms, possibly because unsatisfactory teaching can cause feelings of pessimism and irritability, or because depression cause problems with academic development, which in turn would cause the teaching to be perceived as unsatisfactory.35 Likewise, suffering violence was associated with presenting depressive symptoms, similarly to descriptions in previous studies.36–38

Limitations and strengthsThe study has the following limitations: a) the variable of hours worked per day was self-reported by participants, therefore it is possible that some might have exaggerated the number of hours in the hope that CONAREME might take actions against their hospital facility or reported a lower figure, fearing that actions might be taken against them; b) because the survey was voluntary, it is possible that the response rate might have been lower among those working more hours (as they have less free time) and among those with depressive symptoms (as they may have difficulty performing extracurricular activities like answering surveys), so our sample may under-represent the number of hours worked and the presence of depressive symptoms, and c) the residents who responded to the surveys and were ultimately included differed from those who did not respond, so that residents in surgical specialties, second-year residents and those pursuing residencies in public universities outside of Lima were found to be under-represented, and caution should be exercised with regard to external validity of our results in these groups, as is mentioned in the study report.22

Nevertheless, this study was able to obtain information from a considerable number of residents, and is one of the few studies in the world to have evaluated the association between hours worked and depressive symptoms in resident physicians.

ConclusionsA non-random sample of Peruvian resident physicians was evaluation, finding that 14.6% of the residents surveyed had depressive symptoms. This was directly related to the number of hours worked per day, such that for each additional hour of work per day, the frequency of depressive symptoms increased by 7%.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Alva-Diaz C, Nieto-Gutierrez W, Taype-Rondan A, Timaná-Ruiz R, Herrera-Añazco P, Jumpa-Armas D, et al. Asociación entre horas laboradas diariamente y presencia de síntomas depresivos en médicos residentes de Perú. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:22–28.