The primary objective is to analyse the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the triggers of psychopathology and on the delusional content of patients with psychotic symptoms treated during the first three months of the pandemic in a tertiary hospital in Madrid.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional, observational and retrospective study of all patients attending the psychiatric emergency room (ER) between 11th March and 11th June 2020. Sociodemographic and clinical variables were included. The chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test were performed to compare categorical variables. The level of statistical significance was set at P<.05.

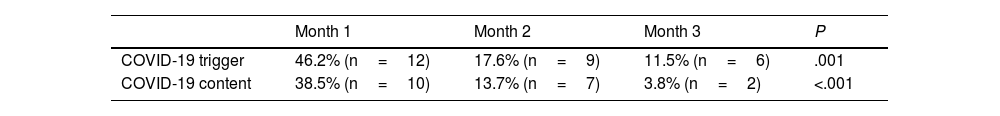

ResultsIn the first month of the pandemic, COVID-19 conditioned the delirious content of 38.5% of the admitted patients and acted as a direct trigger for 46.2% of consultations. In the second week it affected 100.0% of the patients in both cases. Subsequently, a progressive and significant decrease was observed, with COVID-19 being the triggering factor for 17.6% and 11.5% of consultations in the second and third months of the pandemic respectively. Similarly, it was the main determinant of the delusional content in 13.7% and 3.8% of cases respectively.

ConclusionsThe current pandemic affects delirium’s pathoplasty. The delusional content of patients admitted with psychotic symptoms is quickly conditioned, which may be related to the radical change in their life, without transition or prior preparation. The patient’s environmental context and events have a huge impact on the dynamics and characteristics of mental disorders.

El objetivo principal es analizar el impacto de la pandemia por COVID-19 en los desencadenantes de la psicopatología y el contenido delirante de los pacientes con síntomas psicóticos atendidos durante los primeros 3 meses en un hospital terciario de Madrid.

MétodosEstudio transversal, observacional y retrospectivo en pacientes que acudieron a urgencias psiquiátricas entre el 11 de marzo y el 11 de junio de 2020. Se incluyeron variables sociodemográficas y clínicas. Se realizaron las pruebas de la χ2 o el test exacto de Fisher para el contraste de hipótesis de variables categóricas. El nivel de significación estadística se estableció en P<,05.

ResultadosEn el primer mes, la COVID-19 condiciona el contenido delirante del 38,5% de los pacientes ingresados y actúa como desencadenante directo de las consultas en el 46,2% de los casos. En la segunda semana en concreto, afecta al 100% de los pacientes en ambos casos. Posteriormente se observa un descenso progresivo y significativo, y la COVID-19 es el factor desencadenante del 17,6 y el 11,5% de las consultas en el segundo y el tercer mes y el condicionante del contenido delirante en el 13,7 y el 3,8% de los casos respectivamente.

ConclusionesLa actual pandemia afecta a la patoplastia del delirio. El contenido delirante de los pacientes ingresados con síntomas psicóticos se ve rápidamente condicionado, lo que puede estar en relación con el cambio de vida radical, sin transición ni preparación previa. Los acontecimientos y el entorno del paciente tienen un enorme impacto en la dinámica y las características de trastornos mentales.

On 31 December 2019, news came out of the first grouping of cases formed by what would later be identified as a new type of virus of the Coronaviridae family, called SARS-CoV-2. The infection of this virus then spread around the world, until it was recognised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as a global pandemic on 11 March 2020.1 On 14 March, a state of alarm was declared to manage the health care crisis.2 On 4 May 2021, there were 152,534,452 confirmed cases around the world, and a total of 3,544,945 in Spain.3

COVID-19 Is a new disease and, thus, it is understandable that its appearance and spread may generate anguish, anxiety and fear among the population.4 The infection is transmitted rapidly and invisibly, and with a high risk of death. This limits individuals' capacity to use appropriate emotional regulation strategies to cope with the situation, which has often been the case during the COVID-19 pandemic.5

There is substantial evidence from previous studies on the impact that outbreaks of infectious diseases have had on mental health, such as SARS, MERS, and Ebola, in which preventative distancing measures have needed to be adopted.4,6–8 In the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong in 2003, an increase in the number of suicides was observed in the over-65 population, which was linked to greater isolation and increased fear and anxiety.7 Various cases of COVID-19-related suicide in the United States, United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, Bangladesh, India and other countries have been published in the media and in the psychiatric literature.9 Individuals with a history of suicidal ideation, panic disorder, stress, and low self-esteem are highly susceptible to catastrophic thinking.10

In China, after the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic, an increase in negative emotions was observed among the population, to the detriment of a number of positive emotions, which is consistent with studies of previous public health emergencies.11 To understand the psychological and psychiatric impact of a pandemic, the emotions that intervened therein need to be considered. Fear increases the levels of anxiety and stress in healthy individuals12 and intensifies the symptoms of those who have pre-existing psychiatric disorders.12,13 It has been observed that patients infected or suspected of infection with COVID-19 can experience intense emotional reactions, which may evolve into depressive, anxiety, or psychotic disorders, and may even lead to suicide.12,14 This may be particularly prevalent among patients in isolation, whose anguish tends to be greater.12 With regard to psychiatric patients, during the peak of the pandemic in China, a greater risk of suffering post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, irritability or insomnia was observed, as well as an increased propensity to report suicidal ideation in comparison with healthy controls.15

It is worth noting that the population suffering from severe mental disorders, such as psychotic disorders, is particularly vulnerable to situations of threat, measures restricting activity, and changes in daily routines.16 In the current era of digital information and social networks, the proliferation of fake news and conspiracies further contributes to increasing public concern.17 Cases of brief psychotic disorders triggered by stress derived from the COVID-19 pandemic have been reported,17 as well as psychotic decompensation arising from the imposition of mandatory isolation measures in possible cases of COVID-19.16 Also salient in these cases is a delusional content, marked fundamentally by the coronavirus itself.17

Owing to the predictable growth of the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on mental health, in another study, our team has already described the effect of the pandemic on the demand for psychiatric emergency department care and on our brief hospitalisation unit (BHU) during the initial phase. In this work, we focus on describing whether the pandemic or the lockdown have become part of the triggers of the psychopathology present in the patients, and on their possible effect on the delusional content itself of individuals with psychotic symptoms.

Thus, the principal objective is to analyse the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the delusional content of patients seen in the Emergency Department and in the BHU of a tertiary hospital in Madrid (Spain) during the first three months after the declaration of a pandemic by the WHO (from 11 March to 11 June 2020). In line with that observed, it is presumed that, in the same way as in the global society in which we live, the content of the discourse has been impregnated by the current pandemic, the content of the psychopathology of psychiatric patients has been homogenised, and we find a large presence of delusional content related with the coronavirus.

MethodsProcedure and sampleThis work forms part of a larger, cross-sectional, observational, retrospective study.18 Patients aged ≥18 years who attended the psychiatric emergency department at the Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro [Puerta de Hierro University Hospital] in Majadahonda (HUPH) Between 11 March and 11 June 2020 were included.

The medical records of all the patients who consulted during the period have been reviewed. The data collection was conducted by two independent investigators. In the case of any discrepancy, a consensus was reached by consulting a third investigator. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the HUPH.

MeasuresThe following sociodemographic variables were included in the study: age, sex, and mental health hospital referral area. Variables of a clinical nature were also collected: main reason for consultation and diagnosis, type of consultation (voluntary or involuntary), and attitude to follow. In relation to the COVID-19 situation, it was noted whether PCRs were taken for COVID-19 and the results thereof. The presence or absence of triggering factors linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the presence or absence of psychopathological content related to it in patients admitted to the BHU was recorded.

Statistical analysisDescriptive analyses of the categorical variables were made using absolute and relative frequencies, and of numerical variables using the mean±standard deviation. χ2 tests or Fisher's exact test were used for the hypothesis testing of categorical variables. The level of statistical significance was set at P<.05. The statistical package used for data management and analysis was SPSS Statistics, from IBM.

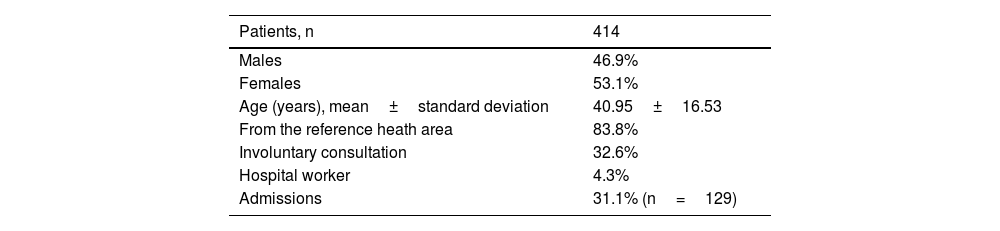

ResultsTable 1 shows the social, demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients seen in psychiatric emergency departments in the period in question. Of the 431 patients who consulted, 414 were seen, given that 14 discharged themselves voluntarily without communication.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients seen in the psychiatric emergency department of the Puerta de Hierro University Hospital from 11 March to 11 June 2020.

| Patients, n | 414 |

|---|---|

| Males | 46.9% |

| Females | 53.1% |

| Age (years), mean±standard deviation | 40.95±16.53 |

| From the reference heath area | 83.8% |

| Involuntary consultation | 32.6% |

| Hospital worker | 4.3% |

| Admissions | 31.1% (n=129) |

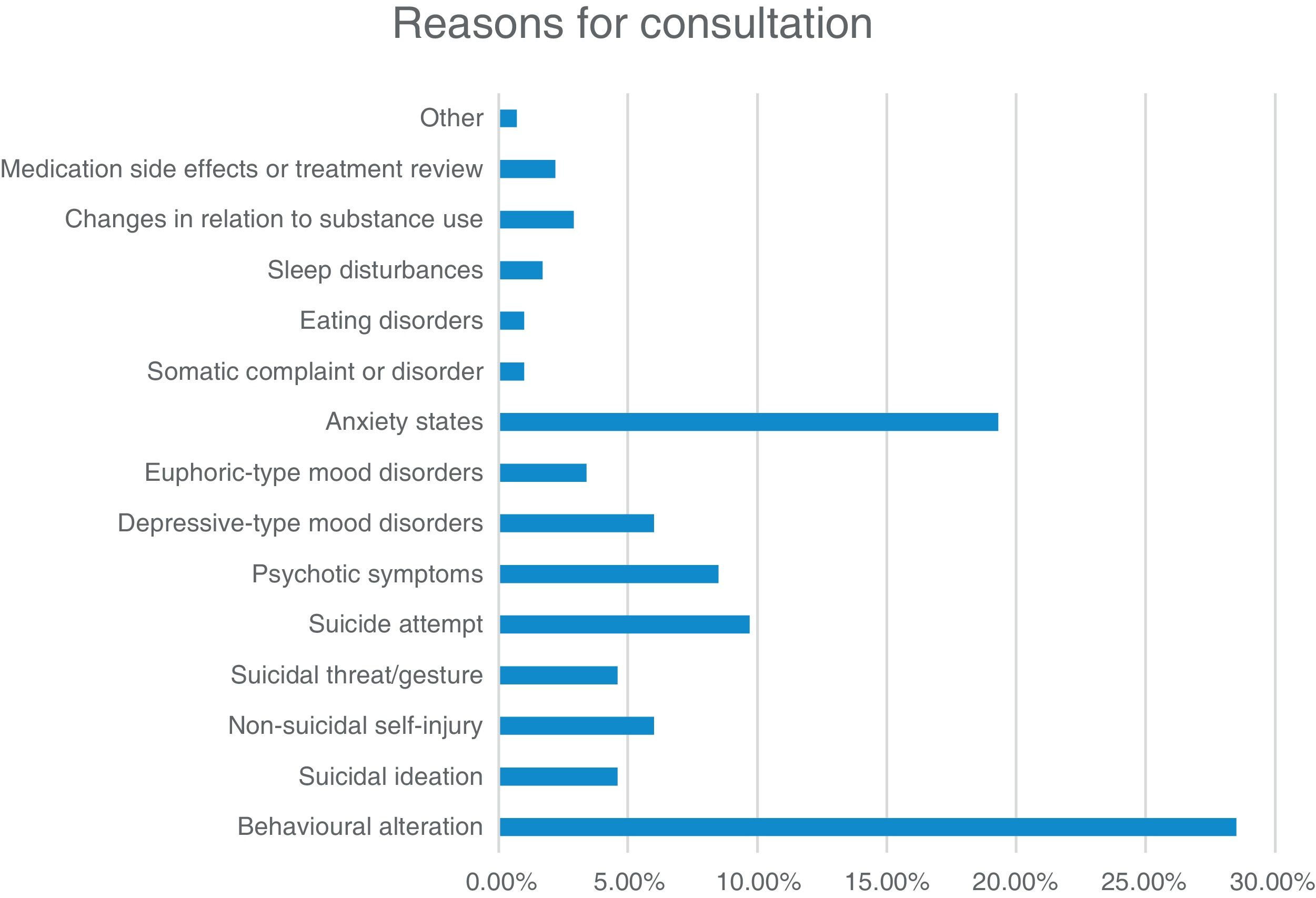

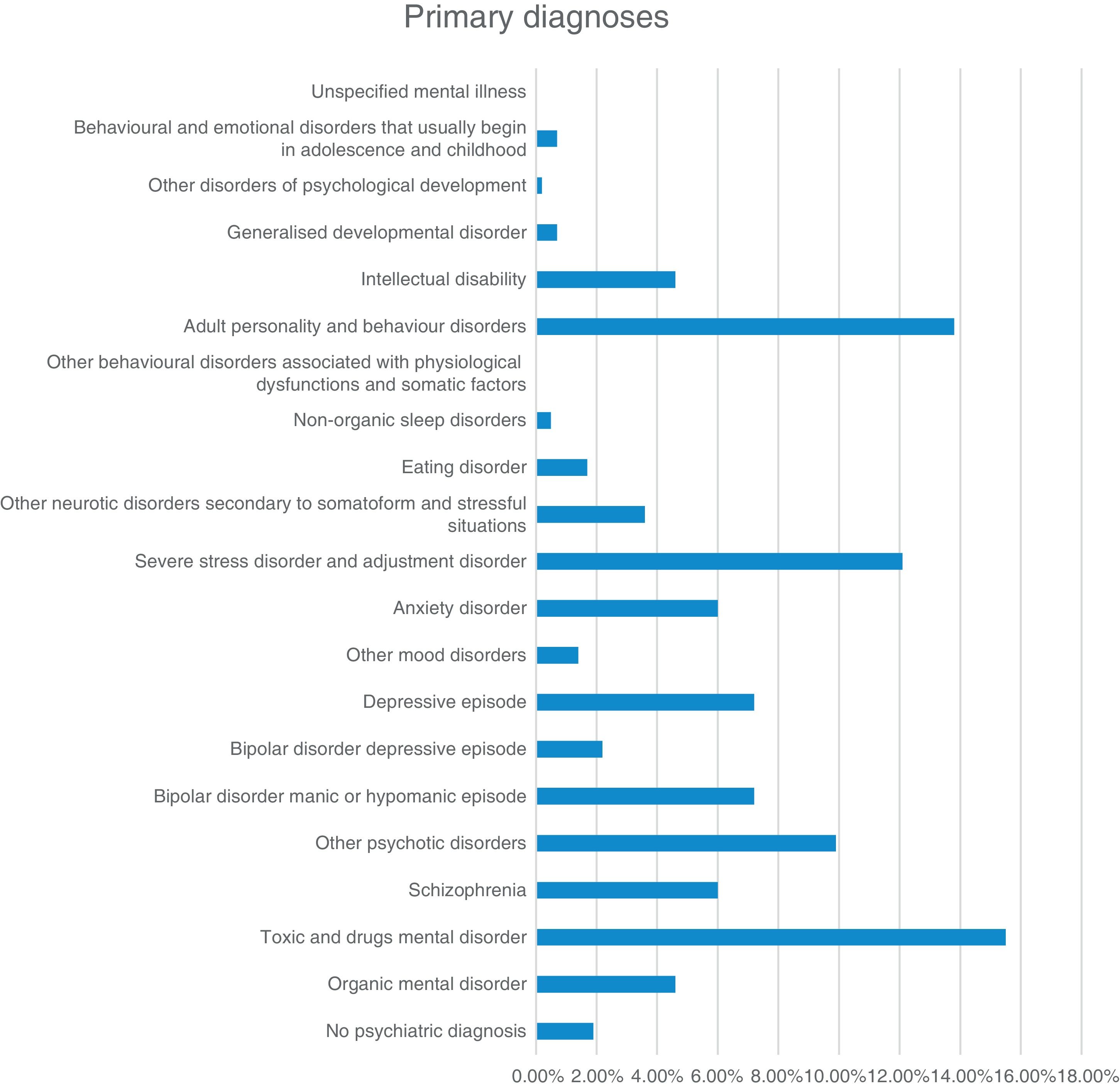

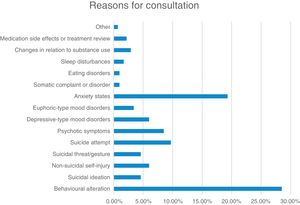

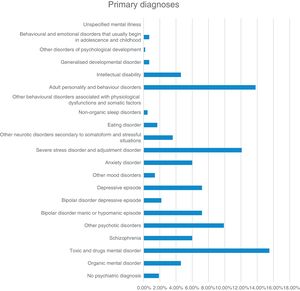

Figs. 1 and 2 show the main reason for consultation and the diagnoses of patients seen in the emergency department during the period described.

Out of a total of 414 seen in the emergency department, 129 were admitted to our hospital's BHU. Of these, a PCR for COVID-19 was taken from 86.0% (n=111), for which the results were negative in all cases.

It was observed that, throughout the three months of the study, 20.9% (n=27) of the patients admitted consulted for some reason directly related with the pandemic. With regard to thought content, in 14.7% (n=19) this was predominantly marked by the coronavirus itself.

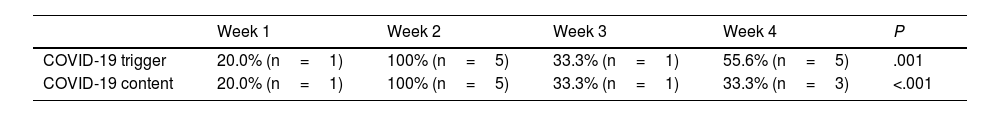

Table 2 shows the evolution by months of the percentage and the number of patients admitted with COVID-19 as the trigger or with content marked by the same. Table 3 shows the evolution by weeks of the same variables during the first month of the pandemic.

Evolution of the percentage and number of patients admitted with a COVID-19 -related trigger or content marked by the same between 11 March and 11 June 2020, by months.

| Month 1 | Month 2 | Month 3 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 trigger | 46.2% (n=12) | 17.6% (n=9) | 11.5% (n=6) | .001 |

| COVID-19 content | 38.5% (n=10) | 13.7% (n=7) | 3.8% (n=2) | <.001 |

Evolution of the percentage and number of patients admitted with a COVID-19-related trigger or content marked by the same during the first month of the pandemic, by weeks.

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 trigger | 20.0% (n=1) | 100% (n=5) | 33.3% (n=1) | 55.6% (n=5) | .001 |

| COVID-19 content | 20.0% (n=1) | 100% (n=5) | 33.3% (n=1) | 33.3% (n=3) | <.001 |

Of the 19 patients admitted with thought content marked fundamentally by the COVID-19 pandemic, the four most representative cases are described below.

Case 1This was a twenty-five-year-old woman, healthcare staff (Resident Biologist Intern), who was admitted on 17 March for a manic episode with psychotic symptoms. The patient had experienced a change in behaviour over the previous three weeks. She presented a rambling, verbose, tangential discourse, with loose associations and loss of the narrative thread. Delusional topics of a mystic/religious nature predominated, as well as the belief of being infected by the coronavirus. The patient was reiterative regarding a male patient who she had assessed over recent weeks and about whom she said “she needed to save, after having observed a cross on one of the clinical samples, which meant that she had to do everything possible to save him”. The patient also asked us to keep our distance from her as “she was infected with coronavirus; she had caught it on the first floor”, and she was insistent on this notion stating that “it had been a human who created the virus”.

Case 2This was a thirty-four-year-old male who was admitted from the emergency department on 18 March for a manic episode with psychotic symptoms. The patient maintained a circumstantial discourse with loose associations and megalomaniacal content, with allusions to his being able to “change the course of things, predict the future and change it”. He referred to messianic themes, although he did not go into detail, only that he had a YouTube channel on which he spoke about such matters and “explained everything in detail”. An interview was held with his family members, who reported behavioural disorganisation of two weeks' duration with episodes of verbal hetero-aggressiveness towards his partner and his family members, with strange behaviour, such as recording videos insulting society. He had also started to declare that “he is the Messiah” and that “it had been him who had provoked the coronavirus through a ritual, and in the same way is able to control it.”

Case 3This was a thirty-four-year-old male who was admitted on 24 March 2020 owing to a psychotic episode with mania-like symptoms related with the consumption of toxic substances. The patient recounted that he was at home with his wife and son when he started to talk about all the ideas and plans he had to solve the problem of the pandemic. He reported that in the month of February, thanks to a workmate of Chinese origin, he had started to realise everything that was going on in the world. He claimed that he could foresee everything that was going to happen, since “What I predicted was proven right”, “I could do away with slavery by making robots work for us”.

His wife reported that, since the home isolation due to the pandemic and the increase in news related with the matter, the patient had started to present manifest behavioural disturbances. As of Thursday, 19 March, his sleep rhythm began to be disturbed, and he was sleeping a total of four hours every two days. She reported an expansive and euphoric mood, with a rambling discourse focused on “plans about how to sort out the world's problems”. “He started to buy pies for the whole building, which he delivered door-to-door”, “He bought various video cameras to make YouTube videos in which he wanted to explain his plans to society and his vision about the virtues of the coronavirus”.

Case 4This was a thirty-year-old male patient admitted on 26 March 2020 for a manic episode with psychotic symptoms. The family reported that, for a period of four days, the patient had been more aggressive, agitated, “with strange ideas; he says that the Chinese are spying on us and that they are recording our calls”.

A jumpy, rambling discourse, with marked distractibility was observed, with loss of the narrative thread. They recounted that a few days previously he had moved to his mother's house to protect his partner, as they lived in a small home and did not feel it was appropriate to isolate under such conditions. They acknowledged that he locked himself in the bathroom and slept in the bathtub to isolate himself. He focused his discourse on his academic-work activity, mixed disjointedly with themes related with COVID-19 infection.

DiscussionDuring the period of the study, it has been possible to observe a change in the delusional content of patients, which is now impregnated by the pandemic and coronavirus. This was more striking during the first month of the pandemic, from 11 March, coinciding fully with the lockdown phase.

Even though the core themes of delusions tend to be the same throughout different periods (persecution, grandiosity, blame, religion, hypochondriasis or jealousy),19,20 clinicians often find that they tend to rapidly incorporate popular current affairs topics.20

In psychiatry, the biological model still considers that the ultimate underpinning of symptoms is their referral to the biological signal that ultimately causes that which is observable to the psychiatrist.21 Nonetheless, being critics of this hegemonic model, there are authors who point out the importance of the context of events and the patient's environment, which have an enormous impact on the dynamics and characteristics of mental disorders.22 This study has focused not so much on the form of psychiatric symptoms, but on their content, on the established fact with the description made of how a specific social context has marked the delusional content of patients with psychotic symptoms. Thus, it is revealed how human psychopathology is always intertwined with the social and cultural reality, how it is related with the particular environment and the circumstances of people's everyday lives.22

With the passing of the weeks, the change in the content of the primary delusions, which it is believed may be due to the environmental circumstances, has been observed longitudinally.23 The social and political situation and technological advances can affect psychiatric patients' delusional beliefs. A few centuries ago, the principal content of delusions of control, persecution and reference involved supernatural entities and witchcraft, which, after the invention of technologies, electricity, X-rays, laser and communication media, such as the telegraph, the telephone, the radio and the television, the content of delusions has been substantially influenced by these innovations.24 Between 1950 and 1995, different authors in Europe described the inclusion of new technologies and cultural innovations in schizophrenic delusions.19 In the 1990s, cases were recorded of patients with delusions related with different socio-political events, such as the criminal trial of O.J. Simpson, the Pope's visit to the United States, the 50th anniversary of the United Nations, and political elections in different countries.25

It is not known how long is required for these cultural innovations to have a bearing of delusional beliefs. For example, after the advent of the Internet, related delusions were not reported until knowledge of the internet became widespread.24 A study from 2006 conducted on 41 individuals with an initial psychotic episode found a relationship between the subject matter of delusions and the content of auditory hallucinations with events that had occurred in the year prior to the onset of the symptoms.26

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on certain mental disorders, such as psychosis, is yet to be determined. It has been proposed that the intense psychological stress associated with a new, potentially fatal disease, such as COVID-19, and the national lockdown restrictions could be triggering factors in a brief reactive psychosis. Cases have been observed of patients with no previous psychiatric history, and previous normal psychosocial adjustment and without COVID-19 infection who presented somatic delusions of infection by the virus. The predominance of spiritual and religious content in the delusions has been notable. The global threat, coupled with an unprecedented overload of information and home isolation could have increased spiritual concerns on an individual level.27

On the other hand, cases have been described of patients with previous mental disorders (bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia) who in the subsequent decompensations have incorporated coronavirus into their delusions or hallucinations.20,28 This illustrates how the current pandemic affects the pathoplasty of delusion. As the situation of the COVID-19 pandemic has been transformed into a topic of concern for the general population, it has increasingly been included in the delusional contents of patients with psychiatric disorders.20 The most striking aspect is the speed of this incorporation. In the second week after the declaration of the state of alarm, 100% of admitted patients had delusional content which revolved homogeneously around the coronavirus. We refer fundamentally to patients already diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders or bipolar disorders with psychotic symptoms who had suffered other previous decompensations in which they presented their own delusional ideations, with different themes in each of them. This rapid and abrupt change observed in the psychopathology could be related with the uncertainty and the deep and critical rupture caused by the virus. In just three days, between the declaration of the pandemic and the declaration of the state of alarm, a radical change took place, with no transition or prior preparation, from one way of life to another. The majority of the external factors which structured our daily lives, such as work, studies, social relations, leisure and hobbies, simply disappeared. Everything came to an abrupt and massive halt. The social component was transformed in such a rapid and global way that it made individual factors virtually disappear, the only external component being the pandemic.

Events of this type (changeable contents in patients with underlying conditions exacerbated by stress or the onset of de novo disorders in vulnerable individuals) brings the essence of the mental symptom to the fore. In order for experience, language, and human behaviour to take the form of a psychiatric symptom, and present certain characteristics (both for their own appearance and pathoplasty and for their classification in the area of abnormality), certain social and practical relations need to be taken into account.21

On the other hand, it has been observed that during the study period, 20.9% of consultations were prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, more striking during the first month (46.2%) and especially in the second week (100%) from the declaration of the pandemic, followed by a progressive decline. The same has occurred with the evolution of the delusional contents of patients. This leads us on to the question of why this decline is observed with the passing of time: could it be due to coming out of the state of alarm? To the return to a “new normal”? One of the possible hypotheses put forward is the existence of a series of mechanisms which make it possible to adapt to the situation of stress as time goes by. The other hypothesis would be that new factors appear, probably related with isolation, cohabitation or lack of activity, among others, and individual factors gain prominence both as triggers and in the content of the thought disturbances, particularly with the end of the state of alarm.

Resilience consists of the maintenance and/or rapid recovery of mental health during and after periods of adversity. It results from a dynamic process of successful adaptation to stressors. These could be both “macro-stressors” (e.g. potentially traumatic events, such as natural or man-made disasters) and “micro-stressors” (the so-called “everyday problems” which, to a certain extent, form part of daily interactions with the environment).29

Although individuals may face the same fear and unknown health risk, not all of them experience the same degree of anxiety or adopt the same number of coping strategies, and considerable individual differences can be observed. On the other hand, the responses for addressing a situation may vary between different situations and over time. In the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong, variations were seen in participants' anxiety responses during the four weeks of a study.30

A study in Germany investigated the course of anxiety and behaviours associated with SARS-CoV-2, as well as the contributory effects of health anxiety, intolerance to anguish, and intolerance to uncertainty in the context of the pandemic. Initially, COVID-19-related anxiety increased, to then go on to stabilise, particularly in April and May 2020. This coincided with a fall in infection rates and the relaxing of certain governmental restrictions. Increased safety and knowledge on the pandemic and an effect of habituation to the threat of the virus could have modified the risk evaluation in relation to the virus and could have led to a reduction in anxiety after March 2020. The results of previous epidemics/pandemics confirm that responses to infectious outbreaks are variable and may decrease during the course thereof.31

Nonetheless, other researchers have pointed out that the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for mental health could persist and reach their peak even later than the pandemic itself. A study to evaluate changes in psychopathological symptoms during and subsequent to the outbreak in China showed that, after the peak, the prevalences of depression and anxiety increased. This could be due to the long-term consequences, such as uncertainty and fear of a financial crisis or recession or increased unemployment.32

The principal strength of this work lies in the fact that it is one of the first to date to analyse and describe the impact of the COVID-19 on the delusional contents of patients admitted to a BHU with psychotic symptoms. Moreover, it highlights the impact of the current pandemic on the reasons for consultation of patients seen during the period described. It should be mentioned that the main limitation is the short observation period; studies that allow us to observe the long-term evolution of the findings described above will need to be conducted.

ConclusionsIt has been seen that the current COVID-19 pandemic affects the pathoplasty of delusion. The delusional content of patients admitted to our BHU was rapidly conditioned by the arrival of the coronavirus, and a homogenisation can be observed, above all, in the second week of the observation period, when the delusional themes focused on the pandemic appeared in 100% of the subjects studied. This may be related to the radical life change, with no transition or prior preparation, which came about in just three days, between the declaration of the pandemic and the declaration of the state of alarm. It can be concluded that the context of events and the patient's environment have an enormous impact on the dynamics and characteristics of mental disorders.

On one hand, a high percentage of patient consultations in the initial period of the study were directly triggered by motives associated with the coronavirus, and with the passing of time, the appearance of other stress factors was observed. While at the start of the pandemic, it functioned practically as a single external component, and individual factors disappeared, as the period of lockdown progressed and especially following the end of the state of alarm, other triggers appeared, probably more related with cohabitation, the lack of activity, financial difficulties, or the socio-cultural conditions of each individual. It is also possible that a number of mechanisms may develop that allow for adaptation to the stressful situation as time goes by.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.