Lockdowns and social distancing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic have brought about the need to continue treatment virtually in patients with Eating Disorders (ED).

ObjectiveTo evaluate feasibility, acceptability and adherence to virtual treatment in patients, families and therapists.

MethodsFourteen patients, 10 family members and eight therapists from an intensive outpatient program for ED answered online surveys and a SWOT analysis was performed with the responses.

ResultsVirtual treatment during lockdown was considered feasible and useful by all respondents. Fear of contagion and the presence of parents in the home were identified as strengths. Parents reported problems with nutritional plan compliance, especially in anorexia patients. Therapists highlighted the importance of methodological adaptations in sessions to improve participation. Adherence to sessions was 100% for family members and 90% for patients.

ConclusionsAdaptation to a virtual program is a valid and useful option during lockdowns. It improves family participation, but does not replace face-to-face treatment.

La cuarentena y el distanciamiento social como resultado de la pandemia de COVID-19 planteó la necesidad de continuar virtualmente el tratamiento de los pacientes con trastornos alimentarios (TA).

ObjetivoEvaluar la viabilidad, aceptabilidad y adherencia al tratamiento virtual de los pacientes, las familias y los terapeutas.

MétodosSe aplicaron encuestas en línea a 14 pacientes, 10 familiares y 8 terapeutas de un Programa Ambulatorio Intensivo para TA, y se realizó un análisis DOFA con las respuestas.

ResultadosEl tratamiento virtual durante el confinamiento fue considerado factible y útil por todos los encuestados. El miedo al contagio y la presencia de los padres en el hogar se identificaron como fortalezas. Los padres informaron problemas con el cumplimiento del plan nutricional, especialmente en anorexia. Los terapeutas señalaron la necesidad de adaptaciones metodológicas en las sesiones para mejorar la participación. La adherencia de las familias fue total y la de los pacientes, del 90%.

ConclusionesLa adaptación virtual del programa es una opción válida y útil durante el confinamiento obligatorio, mejora la participación familiar, pero no reemplaza el tratamiento presencial.

As a result of the rapid spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) across the five continents, the World Health Organisation declared a global public health emergency on 31 January 2020. From the beginning of March, after identifying the first case in a traveller from Europe, the Colombian government established regulations aimed at containing and mitigating the spread of the pandemic, drawing up guidelines for epidemiological surveillance, hygiene and social distancing. Lockdowns were ordered throughout the country from the last week of March. These measures posed great challenges in the treatment of patients with mental illnesses in general, and in particular patients with eating disorders (ED) who were receiving treatment at that time, with this being the area we specifically address in the present article.

Hospital and outpatient services specialised in ED in other countries reported serious obstacles in patient care during the COVID-19 emergency. There was the need for participation of other healthcare professionals, problems of space, increased care costs, rotation of therapeutic teams, reduction of time allocated to psychotherapy, family members' fears of infection, etc.1

In addition, for patients who had already recovered, the risk of relapse increased during lockdown due to aspects such as the change in routines, non-availability of the usual foods, the pressure from the media encouraging countless exercise routines at home so as "not to gain weight", the interruption of activities in gyms.2

A series of strategies and recommendations for patients, families and therapists during the COVID-19 lockdown was recently published in 21 languages, addressing issues related to diet and weight (likelihood of gaining weight, overeating, lack of regular activity, lack of excessive control); including topics related to uncertainty, the risk of infection itself, boredom and loneliness.3 However, beyond psychoeducation and recommendations, it is necessary to continue the treatment and support of these patients and their families, with the additional challenge of providing psychotherapeutic care in conditions of social isolation and in the midst of a pandemic.

In this context, teleconsultation re-emerges as a work tool in mental health. Telemedicine and teleconsultation were initially established by the Australian Government to meet the health needs of rural or remote populations during emergency situations. In Psychiatry, the first experiences with telemedicine, reported by the University of Nebraska, date back to 1972. There is a history of these tools for the treatment of depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, suicide risk, bipolar disorder, self-harm behaviours, grief management, post-traumatic stress disorder and ED, using methods such as video conferences, online forums, smartphone applications and text messages.4

In ED in particular, there are experiences, ranging from nutritional support for patients with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, to cognitive behavioural therapy for bulimia and family-based therapy protocols for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Studies comparing the effectiveness and the cost-effectiveness ratio of cognitive behavioural therapy carried out face-to-face or by telemedicine for patients with bulimia nervosa agree that both are equally effective, but that virtual care costs less.5–10 There have been no reports to date evaluating individual, group and family therapies for patients with ED.

This article reviews the feasibility and acceptability of comprehensive treatment with individual and group virtual psychotherapy and nutritional support for a group of Colombian patients with ED and their families in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, from the viewpoint of patients, their caregivers and the therapists.

MethodsClinical scenarioEquilibrio, in its in-person modality, is an intensive comprehensive outpatient care programme, in which ED patients (teenagers and adults) receive a multidisciplinary multimodal treatment from Monday to Friday consisting of weekly individual sessions of cognitive behavioural psychotherapy along with psychodynamic orientation, medical-psychiatric treatment of the ED and its comorbidities, and nutritional rehabilitation. In addition, patients receive group therapy using various approaches (cognitive-behavioural; dialectical behavioural; work on body image; expressive therapy: art therapy; nutrition workshops). Renutrition is carried out through a nutritional regime designed according to the patient's needs with exposure to all food groups in daily therapeutic meals. At the same time, we work on training family members and caregivers in home treatment strategies, through weekly sessions attended by families, which are an adaptation of the new Maudsley Method.11 Although one of the criteria for entering the programme is the absence of medical or psychiatric life-threatening risk, the patients treated usually have a chronically compromised nutritional condition, which, with the added emotional impact of fear of contagion, the exposure of some patients to the arrival of family members from other countries with high rates of the disease which imposed quarantine, or the presence at home of older people with comorbidities or with immunosuppressant treatments for other disorders, all led to the decision to temporarily discontinue in-person treatment and observe the indications of the health authorities on lockdown.

A virtual teleconsultation strategy for patients and their families was rapidly planned and implemented as an alternative, in order not to leave the care of these people uncovered in the midst of a particularly critical situation. All participants were receiving treatment in the intensive in-person outpatient programme.

Procedures and materialsThis was a cross-sectional descriptive observational study for which three surveys were designed with semi-structured questions, directed at patients, family members and members of the treating team. The surveys consisted of multiple choice questions, eight closed questions (yes or no) and four open questions. A focus group was held with the therapeutic team and representatives of the patients' parents. Therapists took field notes while observing the patients and parents while using the Zoom platform. During the process, all participants were asked to reflect on whether the new virtual treatment scheme was useful or not: its content, its design and its methodology adapted for the sessions and the process of using the platform. They were asked to comment on: any difficulties they may have faced or believed others might face; sessions or components they considered particularly beneficial or deficient; and how they imagined their treatment might continue in the future. We specifically worked with the patients in two of the group sessions on the negative or positive impact of lockdown on eating symptoms, concerns with weight and body image, as well as the potential harm/benefit derived from the pandemic situation on relationships with the family. In another group session, the relationship between exposure to the video camera and their experience with their body image was explored. Using the responses to the interviews, field notes, focus group discussions and group sessions described, the findings were discussed and a SWOT analysis was conducted to explore strengths, weaknesses, opportunities for improvement, and options to resume in-person treatment or not. To assess adherence, a register of participants was taken at each Zoom session.

For the use of teleconsultation, informed consent was obtained on services under the modality of telemedicine to parents and patients which indicated the potential benefits, risks and responsibilities of the intervention. An agenda of individual, group and training psychotherapy sessions was defined for family members and caregivers on home treatment during lockdown, consisting of: two weekly sessions of cognitive behavioural therapy; one follow-up session by Psychiatry; two group sessions per day; one weekly nutrition workshop; and, in addition, multi-family and single-family support and accompaniment sessions. All sessions were one hour long. The group sessions with the patients and the multifamily training groups for parents and caregivers lasted one hour. The single-family support sessions lasted half an hour. At the time of writing, eight weeks of virtual treatment had been completed. A total of 14 patients with ED participated: nine with anorexia nervosa (three atypical anorexias, three restrictive and three combined with purging) and six with bulimia nervosa; 10 family members and eight members of the therapeutic team. Patients ranged from 11 to 23 years old.

ResultsIn general, all the family members and patients considered the virtual scheme of individual, group and family sessions viable. They stated that they preferred the online scheme due to fear of contagion and positively valued the support of the therapists.

The patients highlighted as a strength not having to leave home and being able to be with their family, as well as being able to continue with treatment. Regarding the weaknesses of the online scheme, the patients pointed out the need for "more teaching-orientated" methods during the group sessions and one of them reported connection problems. When giving their opinions about what they would improve, they pointed out the need to have more individual sessions during lockdown, “let us talk more, because they hardly let us talk” (referring to interruptions when participating in group sessions), and take into account the times so that it did not clash with school or university classes. When asked about their desire to return to in-person treatment, half of the patients stated that they would like to return, but if the epidemiological conditions did not improve, they would all like to continue with online treatment.

The family members were unanimous in positively rating the continuity of the treatment so as not to lose the progress made so far, to have the permanent support of the therapists during the quarantine, and to receive the therapists’ modelling for how to proceed at meal times. They also appreciated the convenience of not having to leave the house during the pandemic and the fact of having to make the effort to deal with the disorder at home. However, others described the experience at home as, “a great effort; it's difficult to be with her at all five times, but it's a challenge that I took on with love and I've already got used to it". Others expressed difficulties due to confinement and boredom. Furthermore, the parents' anguish with regard to managing the recommendations for their daughters' diet and adherence to the nutritional guidelines was very evident. In this area, family members responded that the virtual model: "doesn't allow monitoring of eating times, which are key for renutrition"; “There's no support for the difficulties before and after eating, to remove control or prevent the patient's participation in preparing meals at home” and “afterwards, to diffuse anxiety and avoid symptoms”; "Even managing the menu and portions is difficult at home"; "It's very tiring to do the programme at home, as you don’t have all the professional tools to manage the disorder"; or "Adhering to the regimen is really time-consuming". Another expressed his doubts about the methodology in the body image sessions.

In terms of proposals to improve the scheme, the family members responded: "I would include more eating times"; "I would try to develop a relationship more of alliance and support with the parents, instead of what I often perceived as reprimands". Others asked for, “Accompaniment at all five eating times, because the management provided by the therapist is more effective”. They proposed weekly sessions with parents, "because lots of situations come up which are difficult to handle and it's good to have more direct guidance".

Despite this, when we asked family members about the possibility of returning to the in-person programme taking all travel precautions and with a rigorous biosafety plan, only three maintained their preference for the online programme for fear of infection; eight of the nine patients with anorexia preferred to return to face-to-face treatment.

The therapists comprised three psychiatrists, three psychologists and two healthcare professionals working in nutrition. All members of the treatment team conducted group sessions and seven individual sessions, and six conducted sessions with families. Six of the eight team members considered the online scheme to be useful and stated that they felt comfortable doing it. All the respondents thought that the number of participants per session seemed appropriate. Only one of the therapists considered the session time too short. However, all of them agreed that they had experienced some degree of discomfort during the online sessions and that they had experienced problems with connection and with the cameras turned off, which did not allow them to establish eye contact and see whether the patient was present or if they were doing other activities while the session was going on; six observed that the patients did not have enough privacy during the sessions, they were interrupted by their siblings or activities at home; five reported having difficulties in achieving the participation of all patients in the group sessions, and two reported having had difficulties adapting the methodology of the in-person group sessions to the online format.

When asked about the strengths, therapists stated that the online model, "is better than not having any support, but it is inferior to in-person", or that, "the older the patient, the better it works”. Other strengths described were: "Being able to work in the family environment allows us to see how each family and home works, and with this, intervene in situations which generate treatment dysfunction". The nutritionist stated that, “Sharing the screen via Zoom makes the workshop easier. In individual consultations there's more time to write down tasks, menu ideas. Patients can stop and show the meals they eat, their portions, different brands of foods". In general, the therapists considered time availability, frequency of sessions and avoiding travel to be valuable and noted as another strength that, "It helps us gain an insight into how they live and adapt certain strategies to their immediate environment".

When describing the weaknesses of the format, therapists made comments such as; “Maintaining patients' attention when the session doesn't have a dynamic methodology (for example, filling out a worksheet)”; or “Sometimes group sessions don't allow for such a broad discussion, as it depends on the patients' willingness to participate; this isn't a constant, it depends more on the subject matter; of course it forces the therapist to be creative and change the dynamics of the session". Others said that in individual sessions, “The chances of patients being distracted by other things are high,” and that they lose the opportunity to make a physical assessment. Regarding the methodology of the online sessions, they added: "The lack of an observational approach makes it difficult to do more dynamic body image and expressive therapy sessions"; and "The original sessions are designed for face-to-face work and direct interaction, work in pairs or answers on worksheets which are then socialised. This format needs to be reviewed in the online ones". They agreed with the patients' assessment of connection failures. However, in general, the therapists' recommendations pointed out the need to maintain the online format for family sessions and thus guarantee adherence by counteracting the difficulty with schedules and travel; maintain some individual follow-up appointments online for patients; train parents to detect signs of deterioration in nutritional and general status, and adapt the content of the group sessions to methodologies which encourage the participation and interaction of the patients.

As regards adherence at eight weeks, there was full attendance of patients at their individual appointments and of families at their training sessions in home management skills. The parents participation in their daughters' renutrition tasks improved substantially, with them assuming control of food preparation, information about the components of the nutritional regimen, preparations, exchanges and seeking support for critical moments. The parents of patients with anorexia had greater difficulty preventing their daughters' attempts to control food preparation, "negotiating" mealtimes, and emotional restraint. In the group sessions, adherence was total in the first six weeks, but attendance dropped to 11 of the 14 patients, which denotes a certain exhaustion with the online sessions, which also coincided with their class times. Active participation during the group sessions was intermittent for some patients, some turned off the camera, others were playing with their phone, or left mid-session.

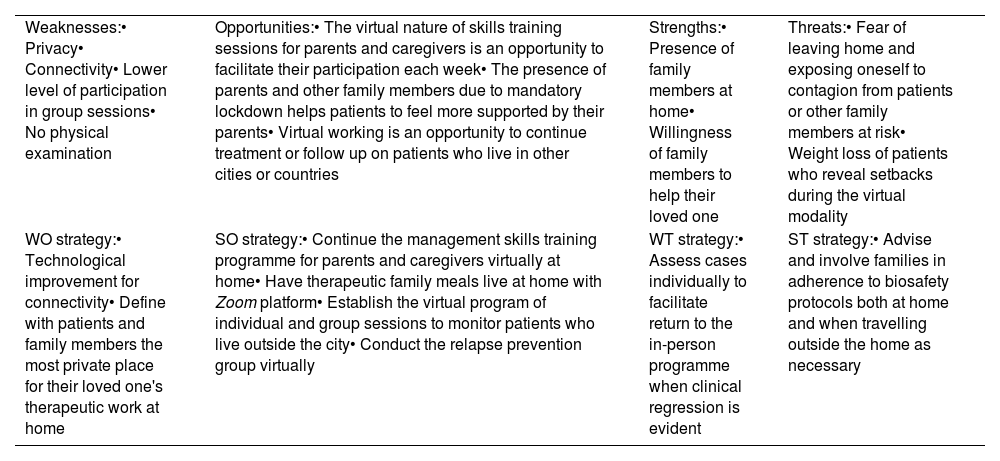

The findings and strategies derived from the SWOT analysis are summarised in Table 1.

SWOT matrix.

| Weaknesses:• Privacy• Connectivity• Lower level of participation in group sessions• No physical examination | Opportunities:• The virtual nature of skills training sessions for parents and caregivers is an opportunity to facilitate their participation each week• The presence of parents and other family members due to mandatory lockdown helps patients to feel more supported by their parents• Virtual working is an opportunity to continue treatment or follow up on patients who live in other cities or countries | Strengths:• Presence of family members at home• Willingness of family members to help their loved one | Threats:• Fear of leaving home and exposing oneself to contagion from patients or other family members at risk• Weight loss of patients who reveal setbacks during the virtual modality |

| WO strategy:• Technological improvement for connectivity• Define with patients and family members the most private place for their loved one's therapeutic work at home | SO strategy:• Continue the management skills training programme for parents and caregivers virtually at home• Have therapeutic family meals live at home with Zoom platform• Establish the virtual program of individual and group sessions to monitor patients who live outside the city• Conduct the relapse prevention group virtually | WT strategy:• Assess cases individually to facilitate return to the in-person programme when clinical regression is evident | ST strategy:• Advise and involve families in adherence to biosafety protocols both at home and when travelling outside the home as necessary |

WT: weakness/threat; WO: weakness/opportunity; ST: strength/threat; SO: strength/opportunity.

For someone with an ED, the physical isolation and limited access to food, added to the permanent state of alert against becoming infected for themselves or their loved ones, the interruption of their routines, the uncertainty and lack of control over the situation, can increase the symptoms of the disorder. On top of that, the poor nutritional status of these patients may increase their risk of virus infection.

Because of the recent situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the available data comes mostly from cross-sectional studies such as telephone surveys. Schlegl et al.12 surveyed 159 patients with anorexia who had left hospital treatment as a result of the pandemic. About 70% of the patients reported greater concerns about their diet, body image and weight, as well as an increased need to exercise to burn calories, feelings of loneliness, sadness and concern about the pandemic. Access to their in-person psychotherapy sessions had been significantly reduced; 26% were receiving follow-up by video conference, and 35% by telephone calls. In patients with bulimia, a notable increase in binge eating, purging and other compensatory behaviours was reported and, equally, a lack of follow-up in their psychotherapeutic and nutritional treatment.13

There are reports that the pandemic has increased both the risk of developing ED and the worsening of symptoms in people already ill.14 The reduction in protective factors against ED (for example, socialisation, development of personal projects) and the increase in barriers to receiving treatment, already problematic before lockdown, aggravate the situation. Disruption of daily routines and restriction of outdoor activities can increase weight concerns and negatively affect eating patterns, exercise, and sleep patterns, which in turn increase the symptoms of the ED. In addition, the deterioration of patients with ED during lockdown has been associated with prior higher rates of anxiety and depression and poorer coping and emotional regulation strategies.15–17

Besides the worsening eating symptoms during mandatory lockdown and the disturbing role of the video camera described, major components of anxiety arise when faced with the uncertainty, the fear of infection or the loss of loved ones and the management of multiple aspects of grief derived from the sudden interruption of social, academic or work life and other aspects, such as fear of job loss or reduction in family income, or concern about caring for older adults in the family. In other words, there are multiple stress factors that ED patients and their families have to face, which helps create the perfect scenario for the worsening of the eating-related symptoms and the anxiety and/or depressive symptoms that tend to accompany ED.

In a group session about eating symptoms during quarantine and the coping strategies used, patients noted an increase in obsessive concerns about food, weight and body image. They all reported having increased the restriction due to the fear of gaining weight, as well as remaining hyperactive or doing more strenuous exercise routines, performing more rituals in front of the mirror, such as checking bone prominences, checking the calorie content of food, checking food preparation more at home and trying to skip meals, especially snacks. Patients with bulimic symptoms also reported an increase in snacking throughout the day, and an increase in purging. In another session, all of them expressed their unease in exposing themselves to the video camera, which has increased rituals and avoidance behaviours and self-image checks; they looked for angles that seemed more favourable to them or put on make-up before appointments to hide perceived flaws. Switching off the camera is one option for controlling the anxiety of exposing themselves both to others and to their own image in the box that appears on the screen. The video camera becomes "another mirror" that is very disturbing and interferes with the patients' concentration in the session. One patient expressed greater concern with her body image when exposed to the camera than she typically experiences during in-person social interactions. Another acknowledged that at least in front of the camera she can "control" that her entire body is not seen, but only her face, turning it off or on, while in face-to-face social relationships she feels much more scrutinised by the others’ gaze. Patients report greater concern between one session and another as to the possible changes in their physical appearance ("looking fatter") or create space for the fantasy of being able to lose all the desired weight during the quarantine so that when lockdown is over, and they return to their social and academic life, they will have already achieved their desired body.

The risks of interrupting treatment in ED patients, however, as we have stated before, are twofold. Immunological alterations in ED patients are well known. The altered cellular immunity in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa is reflected in the changes found in bone marrow, lymphocyte count and altered cytotoxic T helper cell ratio (CD4/CD8); an increase in the secretion and concentration of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin 1 and 6 and tumour necrosis factor alpha being a strong indication of a deregulated immune system.18–20 This situation may, on the one hand, mean a potential increase in the risk of infection and/or complications deriving from it, but on the other, the sudden interruption of in-person treatment may lead to setbacks in the recovery process, with deterioration in physical and mental health making clinicians refer patients to the hospital at the riskiest time. This was precisely the dilemma that parents, patients and therapists faced during the first general lockdown, and we chose to continue the treatment with online sessions, the assessment of which led to this article.

The other people affected in this situation are the family members and caregivers. During the COVID‐19 pandemic, the main problem faced by families of people diagnosed with an ED was limited access to medical resources, including difficulties in going to hospitals, obtaining medications and maintaining treatment as before, especially for outpatients. This situation aggravated the caregivers' feeling of burden, on top of the levels of anxiety and depression they already tend to experience. Mandatory lockdown also contributed to relationship problems becoming visible within the family nucleus, with unresolved conflicts and expressed emotions becoming more marked, all of which can lead to acts of abuse and domestic violence and, at the same time, aggravate the patients’ levels of suffering and the family's difficulties in coping with their role as caregivers of their loved one who is ill.

The effectiveness of online psychoeducation programmes for caregivers of patients with ED was assessed by Guo et al. in 2020. The authors monitored the anxiety and depression levels of a group of caregivers during the pandemic in China and compared them with a control group. Caregivers of patients with ED showed significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety than the comparator group. The online education programme did not show any significant effect in reducing the levels of depression and anxiety of caregivers of patients with ED in general. In caregivers of patients with a longer illness duration, their anxiety levels were less likely to decrease.21,22 In our study, caregivers were very receptive, endorsing the virtual intervention and recognised its advantages. However, those whose daughters had anorexia nervosa had great difficulty taking control of their daughters' renutrition, adhering to the prescribed nutritional regimen, avoiding "supervision" of their daughters in the preparation of menus and managing conflicts at meal times. Four of the patients with anorexia lost weight and the remaining five did not gain weight. The exhaustion from the role of caregiver was evident. Parents expressed fears of fighting an “all-out battle” at mealtimes, which would disrupt the relationship between all family members. Some caregivers followed a different plan from the Equilibrio nutritional guideline being implemented before the pandemic, agreeing with their daughters on safer foods, portions and preparations at meal times. They stated that the firm stance taken by the therapeutic team during meals at Equilibrio was very difficult to achieve. They did not have the support of the other patients in the group or the therapists in-person pointing out dysfunctional rituals and behaviours and avoiding compensations. For this aspect, the proposal to resume in-person treatment came from the families of these patients. It can be said that, although parents, patients and therapists considered online treatment during the pandemic to be viable and accepted its implementation, and the fact that adherence to the sessions in terms of attendance was very good, adopting the therapeutic indications at home exposed difficulties. Lockdowns and quarantines pose challenges to families and patients which not only require flexible thinking, adjustment to changes and mobilisation of adaptive strategies to improve coexistence, but also self-care and the importance of caring for others, and a sense of community.

Comprehensive ED treatment via telemedicine lacks evidence because the studies covering it to date come from in-person treatments, which allow risks to be monitored and other aspects, such as weighing patients to be performed. Moreover, the studies carried out remotely did not take place in situations involving lockdown due to a pandemic. Waller et al.23 recently discussed some points to consider in cognitive behavioural therapy for ED patients via telemedicine when face-to-face treatment is not possible. They include the concerns of patients and clinicians about telemedicine, the changes in the environment and the methodological adaptations required.

In our study, the online experience of individual and group treatment was accepted, with the understanding that it was a temporary measure to continue the process and prevent deterioration in the patients' conditions. Moreover, the adherence of the families to their daughters' treatment regimens was significantly greater than the in-person treatment, thanks to the very lockdown which required parents to stay at home with their children, and not having to travel to our centre during rush hour, as happens under normal conditions.

Although the in-person management protocol of the Equilibrio programme has components of family-based therapy, such as therapeutic family meals and constant training for parents and caregivers to develop management skills at home, the online accompaniment of therapists to patients and families during some "live" mealtimes was very well received. However, despite the support and training they receive, the difficulties that parents continue to have been brought to light: managing the moments before, during and after meals; complying with the nutritional guidelines; and taking control in the preparation of food. This was especially evident in cases of anorexia nervosa. The parents stressed their exhaustion in the task of renutrition and the important role of the therapists in the face-to-face treatment regimen. In general, the therapists observed better participation in the older patients than in the young girls in the group sessions.

In other aspects, however, such as assessing risk to life, which is carried out daily in the in-person programme, checking weight and for changes in vital signs, and assessing suicide risk, checking for self-harm check, etc, the clinicians pointed to the limitations of the online model. As Waller points out, face-to-face work allows the clinician to monitor progress or setbacks day by day, working in privacy, behind closed doors; a mode that facilitates the exploration of suicidal thoughts, behaviours or plans.22 Similarly, in the online model, interruptions are another limitation, not only due to connection problems, but also due to the interference of email alerts or text messages, such as those that pop up on the screen when the patient and therapist are connected.

ConclusionsThe situation of lockdown and quarantines due to the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the conditions for patients with ED by adding more concerns with weight, body image and eating and increasing purging behaviours, as other authors have reported. The virtual adaptation of a comprehensive management protocol was a viable and well-accepted strategy at the beginning, but despite parental commitment and efforts to adopt management indications at home, it cannot replace in-person treatment. Although telemedicine is an option in times of pandemic, patients with ED require direct exposure to all types of foods, at least in the early stages of treatment, to achieve renutrition and control compensatory behaviours and dysfunctional rituals. With online treatment, we also lose the direct interaction with other patients which nourishes the group process, and the monitoring of vital signs and physical examination, all essential in patients with ED in the acute phase. The inclusion of the camera in the sessions for patients with ED adds another disturbing aspect which can become "another mirror", increasing checking and avoidance behaviours and concerns with body image. However, for our programme, the online treatment experience had some positive outcomes, such as consolidating the patient follow-up processes and maintaining the training programme for parents and caregivers online, with greater adherence from them.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.