Little is known about the incidence of delirium and its subtypes in patients admitted to different departments of university hospitals in Latin America.

ObjectiveTo determine the incidence of delirium and the frequency of its subtypes, as well as its associated factors, in patients admitted to different departments of a university hospital in Bogotá, Colombia.

MethodsA cohort of patients over 18 years of age admitted to the internal medicine (IM), geriatrics (GU), general surgery (GSU), orthopaedics (OU) and intensive care unit (ICU) services of a university hospital was followed up between January and June 2018. To detect the presence of delirium, we used the CAM (Confusion Assessment Method) and the CAM-ICU if the patient had decreased communication skills. The delirium subtype was characterised using the RASS (Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale). Patients were assessed on their admission date and then every two days until discharged from the hospital. Those in whom delirium was identified were referred for specialised intra-institutional interdisciplinary management.

ResultsA total of 531 patients admitted during the period were assessed. The overall incidence of delirium was 12% (95% CI, 0.3–14.8). They represented 31.8% of patients in the GU, 15.6% in the ICU, 8.7% in IM, 5.1% in the OU, and 3.9% in the GSU. The most frequent clinical display was the mixed subtype, at 60.9%, followed by the normoactive subtype (34.4%) and the hypoactive subtype (4.7%). The factors most associated with delirium were age (adjusted RR = 1.07; 95% CI, 1.05−1.09), the presence of four or more comorbidities (adjusted RR = 2.04; 95% CI, 1.31−3.20), and being a patient in the ICU (adjusted RR = 2.02; 95% CI, 1.22−3.35).

ConclusionsThe incidence of delirium is heterogeneous in the different departments of the university hospital. The highest incidence occurred in patients that were admitted to the GU. The mixed subtype was the most frequent one, and the main associated factors were age, the presence of four or more comorbidities, and being an ICU patient.

Poco se conoce acerca de la incidencia del delirio en pacientes hospitalizados en diferentes servicios de hospitales universitarios en Latinoamérica y de los subtipos que se presentan.

ObjetivoDeterminar la incidencia del delirio, la frecuencia de los subtipos motores y los factores asociados en pacientes hospitalizados en diferentes servicios de un hospital universitario en Bogotá, Colombia.

MétodosSe dio seguimiento a una cohorte de pacientes mayores de 18 años hospitalizados en los servicios de Medicina Interna, Geriatría, Cuidado Intensivo, Cirugía General y Ortopedia de un hospital universitario entre enero y junio de 2018. Para identificar la presencia de delirio, se utilizó la escala CAM (Confusion Assessment Method) y la CAM-ICU si el paciente presentaba disminución de las capacidades de comunicación. El subtipo de delirio se caracterizó utilizando la escala RASS (Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale). Los pacientes fueron valorados el día de ingreso y luego cada 2 días hasta su alta hospitalaria. Se derivó a los pacientes en quienes se identificó delirio para tratamiento especializado interdisciplinario intrainstitucional.

ResultadosSe evaluó a 531 pacientes que ingresaron durante ese periodo a los servicios mencionados. La incidencia global del delirio fue del 12% (IC95%, 0,3–14,8). En orden descendiente, el 31,8% de los pacientes hospitalizados en el servicio de Geriatría, el 15,6% en Cuidado Intensivo, el 8,7% en Medicina Interna, el 5,1% en Ortopedia y el 3,9% en Cirugía. El subtipo motor más frecuente fue el mixto (60,9%), seguido por el normoactivo (34,4%) y el hipoactivo (4,7%). Los factores asociados con la incidencia del delirio fueron la edad (RR ajustada = 1,07; IC95%, 1,05−1,09), la presencia de 4 o más comorbilidades (RR ajustada = 2,04; IC95%, 1,31−3,20) y la hospitalización en Cuidado Intensivo (RR ajustada = 2,02; IC95%, 1,22−3,35).

ConclusionesLa incidencia del delirio es heterogénea en los diferentes servicios del hospital universitario. La mayor incidencia se presentó en pacientes ingresados en el servicio de Geriatría; el subtipo más frecuente fue el mixto y los principales factores asociados fueron la edad, la presencia de 4 o más comorbilidades y la hospitalización en Cuidado Intensivo.

Delirium, included for the first time as a clinical entity in the DSM-III of 1980, is a disturbance in attention and awareness that develops over a short period of time, usually hours or days,1,2 tends to fluctuate in severity during the course of the day, and may be accompanied by disorientation, cognitive impairment, memory deficit, impaired language and visuospatial ability or perception.1–3

This condition is common in hospitalised patients, especially those admitted to intensive care units (ICU), where frequencies of up to 80% have been reported,3 and in elderly patients.4–6 Despite its known association with longer hospital stays, re-hospitalisations, increased hospital costs, risk of long-term cognitive impairment and increased mortality,7–9 it tends to be an underdiagnosed condition, probably due to its fluctuating nature, the overlap with depression or neurocognitive disorders and the lack of systematic application of formal hospital assessment instruments.

In Colombia, only a few studies have been performed that measure the incidence of this disorder, and the validity of many of these studies is questionable, given that no active searches for delirium are performed, or patients are not monitored throughout their full hospital stay.10–14 In a study conducted at our institution, a global incidence of delirium of 18.6% was found, with a higher percentage (60%) among patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). However, as in many of the published studies, the motor subtype was not classified and the sample size (160 patients) limited the likelihood of being able to compare the incidence between different departments.15

There are four delirium motor subtypes: hyperactive, hypoactive, mixed and no motor subtype. Despite methodological problems faced when defining the delirium subtypes, the motor-activity profile is considered clinically relevant for their detection, and their relationship with other neuropsychiatric diagnoses, comorbidities, aetiology and treatment. Several studies have shown that the presence of a neurocognitive disorder, a prolonged duration and a hypoactive motor subtype are associated with a worse prognosis.6,16–18

The aim of this study is to determine the incidence of delirium, to classify the motor subtype, to explore associated factors and to establish comparisons between the Surgery, Orthopaedics, Geriatrics and Internal Medicine departments and the ICU of Hospital San Ignacio (HUSI) in Bogotá.

MethodsThis study describes a unique cohort of patients over 18 years of age admitted to the ICU and the Internal Medicine, Geriatrics, Orthopaedics and General Surgery departments of a high-complexity hospital during the first half of 2018.

Patients who were delirious or unconscious, or who were receiving antipsychotics, at the time of admission, were excluded. On day one of admission and then every 2 days while in the hospital, patients were assessed using the CAM (Confusion Assessment Method) or the CAM-ICU scales validated in Spanish and for Colombia.19 The delirium motor subtype was characterised using the RASS (Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale).20,21 Trained personnel were responsible for applying the scales and for collecting data. Most were residents from the general psychiatry and liaison psychiatry specialties. An institutional interdisciplinary group was responsible for treating the patients.

The cumulative incidence of delirium and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated, classified by sex, age, marital status, profession, hospital department and number of comorbidities. If a patient had more than one episode of delirium during their time in the hospital, only the first episode was quantified to calculate the incidence. For each variable, the relative risk (RR) was estimated, which was adjusted using a Poisson model for the variables of age, widowhood status, hospital department and number of comorbidities. The Stata 15.0 software tool was used for data processing and analysis.

The research protocol was submitted to the Ethics and Research Committees of the Faculty of Medicine and the hospital. All patients provided their written consent.

ResultsA total of 531 patients who were admitted to the ICU and to the Internal Medicine (IM), Geriatrics, General Surgery and Orthopaedics departments were assessed and voluntarily gave their consent to participate. The sociodemographic data, hospital department and number of comorbidities are shown in Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and number of comorbidities in 531 hospitalised patients during the first half of 2018.

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Age | 65 [48−79] |

| Female | 261 (49.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 105 (19.8) |

| Married | 206 (38.8) |

| Divorced | 45 (8.5) |

| Widowed | 95 (17.9) |

| Cohabiting | 80 (15.1) |

| Profession | |

| Student | 18 (3.4) |

| Unemployed | 140 (26.4) |

| Vocational | 169 (31.8) |

| Undergraduate | 63 (11.9) |

| Retired | 141 (26.6) |

| Education (years) | 10 [5–11] |

| Comorbidities | |

| None | 26 (4.9) |

| 1 | 179 (33.7) |

| 2 | 168 (31.6) |

| 3 | 102 (19.2) |

| 4 or more | 56 (10.5) |

Values are expressed as n (%) or median [interquartile range].

The age of the patients ranged between 18 and 96 years, with differences in medians between the different departments (53.9 years for patients in the Surgery department, 56.8 for those in Orthopaedics, 58.4 for those in Internal Medicine, 59.4 for patients in the ICU and 84.6 for those in Geriatrics). Half of the patients were elderly adults and 25% were 80 years of age or above. Although more men were admitted than women, this difference was small (50.8 compared to 49.2%). With regards to marital status, the frequency with which the patients reported being single, widowed or divorced is noteworthy (46.1%), and more so in women (59.8%) than in men (33%). Most patients had one or more comorbidities (95.1%).

The overall incidence of delirium, with its confidence intervals and broken down by department are shown in Table 2. Statistically significant differences were evident in the incidence of delirium in patients admitted to the Geriatrics department compared to those admitted to the Orthopaedics, Internal Medicine and Surgery departments. However, despite a higher relative risk for patients admitted to the Geriatrics unit, no statistically significant differences were found with respect to the other departments. The mixed motor subtype was the most common (60.9%), followed by no motor subtype (34.4%) and the hypoactive motor subtype (4.7%). No statistically significant differences were found in the incidence of mixed and hypoactive delirium between the departments.

Incidence of delirium and relative risks per hospital department.

| Department | Patients, n | Incidence (95% CI), % | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delirium | Total | |||

| Surgery (comparator) | 4 | 102 | 3.92 (0.15−7.69) | — |

| Internal Medicine | 13 | 150 | 8.67 (4.16−13.17) | 2.21 (0.74−6.59) |

| Intensive Care | 15 | 96 | 15.63 (8.36−22.89) | 3.98 (1.37−11.58) |

| Orthopaedics | 5 | 98 | 5.10 (0.75−9.46) | 1.30 (0.36−4.70) |

| Geriatrics | 27 | 85 | 31.76 (21.87−41.66) | 8.10 (2.95−22.24) |

| Total | 64 | 531 | 12.05 (9.28−14.82) | |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; RR: relative risk.

With regards to associated factors, statistically significant differences were found in the incidence and relative risk of delirium as age increased, for widowhood status and in the presence of four or more comorbidities (Table 3).

Incidence of delirium and relative risks according to age, sex, marital status, professional status and number of comorbidities.

| Variables | Cases (n/N) | Incidence of delirium (95% CI), % | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.06 (1.04−1.08) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male (comparator) | 26/270 | 9.6 (6.1−13.1) | — |

| Female | 38/261 | 14.6 (10.3−18.8) | 1.51 (0.95−2.42) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single (comparator) | 7/105 | 6.7 (1.9−11.4) | — |

| Married | 25/206 | 12.1 (7.7−16.6) | 1.82 (0.81−4.07) |

| Divorced | 7/45 | 15.6 (5−26.1) | 2.33 (0.87−6.27) |

| Widowed | 18/95 | 18.9 (11.1−26.8) | 2.84 (1.24−6.5) |

| Cohabiting | 7/80 | 8.8 (2.6−14.9) | 1.31 (0.48−3.59) |

| Professional status | |||

| Student (comparator) | 1/18 | 5.6 (0−16.1) | — |

| Unemployed | 27/140 | 19.3 (12.8−25.8) | 3.47 (0.5−24.03) |

| Vocational | 10/169 | 5.9 (2.4−9.5) | 1.07 (0.14−7.85) |

| Undergraduate | 5/63 | 7.9 (1.3−14.6) | 1.43 (0.18−11.46) |

| Retired | 21/141 | 14.9 (9−20.8) | 2.68 (0.38−18.75) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| 0 | 1/26 | 3.8 (0−11.2) | — |

| 1 | 7/179 | 3.9 (1.1−6.8) | 1.02 (0.13−7.93) |

| 2 | 17/168 | 10.1 (5.6−14.7) | 2.63 (0.37−18.94) |

| 3 | 20/102 | 19.6 (11.9−27.3) | 5.10 (0.72−36.25) |

| 4 or more | 19/56 | 33.9 (21.5−46.3) | 8.82 (1.25−62.4) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; RR: relative risk.

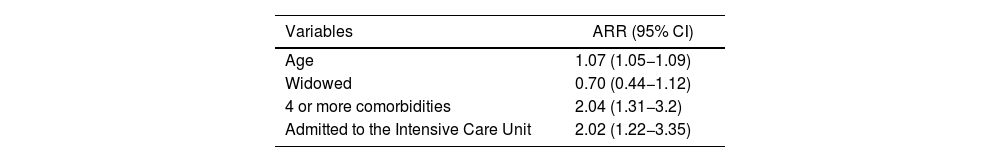

After adjusting the model for age in years, marital status, number of comorbidities and hospital unit, the results shown in Table 4 were obtained.

Relative risk of delirium adjusted for age, marital status, number of comorbidities and hospital department.

| Variables | ARR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Age | 1.07 (1.05−1.09) |

| Widowed | 0.70 (0.44−1.12) |

| 4 or more comorbidities | 2.04 (1.31−3.2) |

| Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit | 2.02 (1.22−3.35) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; ARR: adjusted relative risk.

According to this model adjusted for the aforementioned variables, there are statistically significant differences in the risk of delirium according to age, presence of four or more comorbidities and admission to the ICU.

DiscussionThe general incidence of delirium found may be considered low for a hospital with tier 4 level of complexity, and is also lower than the incidence previously reported at this institution.15,22 We consider that both the current low incidence of delirium and its decrease over time are related to the implementation of an institutional policy for interdisciplinary treatment based on multi-component interventions that include environmental-based interventions, permanent review of drug interactions and de-prescribing for patients who are receiving multiple medications. Multi-component interventions in patients who are at risk of delirium have been shown to be effective in the prevention of delirium,23,24 with statistically significant decreases in the incidence of delirium and in the frequency of in-hospital falls and costs of medical care.23–25

Likewise, the low incidence found in patients admitted to the ICU may be related to the aforementioned institutional policy, plus the prescription of central alpha-2 agonists for patients requiring conscious sedation or to be kept under deep sedation,26 and to an "open door" component in which the visit schedule is free, broad and flexible. As a result, our institution can be considered a "friendly hospital for the prevention of delirium".24,27

The finding of a statistically significant relationship between age and the incidence of delirium agrees with the findings of several studies.16,17,28 The mixed motor subtype as the most common variant of delirium and the low frequency of the hypoactive variant may be related to the early diagnosis implemented in this study, together with the fact that patients were assessed by liaison psychiatry specialists, and patients whose primary symptoms were attributable to depression were labelled as having delirium, a bias that is often reported in the literature.28–30 However, our study was not designed to specifically explore these associations and these should therefore be clarified in subsequent research.

The prospective nature of the follow-up of patients admitted to the selected hospital departments and early identification of those patients who were starting to experience delirium support the validity of the results presented. However, the results are also limited by the fact that other risk factors were not assessed, such as the specific use of high-risk medications, standardised nutritional assessment guidelines, sensory deprivation or acute phase biomarkers.31

FundingThis research was performed during the time that the authors were under contract with the Faculty of Medicine of the Pontifical Javeriana University in Bogotá and San Ignacio University Hospital. Project Number FM-CIE-0493-17.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest for this study.