To describe pharmacological and non-pharmacological practices for delirium, carried out by psychiatry residents and psychiatrists in Colombia.

MethodsAn anonymous survey was conducted based on the consensus of experts of the Liaison Psychiatry Committee of the Asociación Colombiana de Psiquiatría [Colombian Psychiatric Association] and on the literature review. It was sent by email to the association members.

Results101 clinicians participated. Non-pharmacological preventive measures such as psychoeducation, correction of sensory problems or sleep hygiene are performed by 70% or more. Only about 1 in 10 participants are part of an institutional multi-component prevention programme. The preventive prescription of drugs was less than 20%. Regarding non-pharmacological treatment, more than 75% recommend correction of sensory difficulties, control of stimuli and reorientation. None of the participants indicated that the care at their centres is organised to enhance non-pharmacological treatment. 17.8% do not use medication in the treatment of delirium. Those who use it prefer haloperidol or quetiapine, particularly in hyperactive or mixed motor subtypes.

ConclusionsThe practices of the respondents coincide with those of other experts around the world. In general, non-pharmacological actions are individual initiatives, which demonstrates the need in Colombian health institutions to commit to addressing delirium, in particular when its prevalence and consequences are indicators of quality of care.

describir las prácticas farmacológicas y no farmacológicas para el delirium, realizadas por residentes de psiquiatría y psiquiatras en Colombia.

Métodosencuesta anónima basada en el consenso de expertos del Comité de Psiquiatría de Enlace de la Asociación Colombiana de Psiquiatría y en la literatura. Enviada por correo electrónico a los adscritos a la asociación.

ResultadosParticiparon 101 clínicos. Las medidas preventivas no farmacológicas como psicoeducación, corrección de problemas sensoriales o higiene del sueño son realizadas por el 70% o más. Solo cerca de uno de cada 10 hace parte de algún programa multicomponente preventivo institucional. La prescripción preventiva de fármacos fue menor del 20%. Respecto al tratamiento no farmacológico, más del 75% hace corrección de dificultades sensoriales, control de estímulos y reorientación. Nadie indicó que en su centro la atención esté organizada para potenciar el tratamiento no farmacológico. El 17,8% no usa fármacos en el tratamiento. Los que los usan prefieren haloperidol o quetiapina, especialmente en casos hiperactivos o mixtos.

ConclusionesLas prácticas de los encuestados coinciden con las de otros expertos en el mundo. En general, las acciones no farmacológicas son iniciativas individuales, lo que evidencia la necesidad de que las instituciones colombianas de salud se comprometan con el abordaje del delirium, especialmente cuando su prevalencia y consecuencias son indicadores de calidad en la atención.

Delirium is a clouding of consciousness that occurs with impaired alertness (but before stupor, coma or deep sedation) as a result of various health conditions. This altered state of consciousness is characterised by deficits in cognition (predominantly attention difficulties), circadian rhythm and higher-order thinking.1 This psychiatric disorder is known to be highly prevalent in general hospitals, where one in every five patients suffers from it at some point.2 Those who do are at risk of medical complications, as well as institutionalisation,3 irreversible brain damage and dementia.4 The disorder increases the duration of hospitalisation and the likelihood of dying during or after its resolution.5–7 To this is added the risk of complications such as post-traumatic stress.8

The clear knowledge of the epidemiology and consequences of delirium stands in contrast to the lack of consensus on tackling it. The need to detect and resolve the health conditions involved in its aetiology is agreed, but other therapeutic measures beyond that are subject to debate. Although a biopsychosocial approach involves pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions in prevention and treatment, the quality of the evidence backing the relevant guidelines and the willingness of health institutions to implement standardised measures are limited.1,9

It is not known with certainty whether preventive pharmacological interventions reduce the risk of delirium or if they decrease episode duration. The indication for medications in treatment is also debated; indeed, there is not even a consensus on whether antipsychotics are for managing symptoms or if they act on the pathophysiological mechanisms of the condition.10 The panorama for prevention and non-pharmacological treatment is no better. Intervention packages have been proposed, as have systems of working that require some degree of training of the treatment teams and of investment in health institutions. The efficacy of these approaches or of their individual components are difficult to verify in rigorous trials. Furthermore, real-life implementation of these interventions is arduous due to a lack of agreement on which patients benefit, to staff changes or to the workload.11

Psychiatry is the medical speciality with the most extensive knowledge of the biopsychosocial model, particular to approaching delirium. Therefore, in light of the debatable quality of the evidence, it is important to ask these specialists about their practices with regard to tackling the disorder. Although physicians are known for their low survey response rates, such questionnaires should still be used, since it has been found that those who do not participate do not differ substantially from those who participate.12 In view of these considerations, the objective of this study was to learn, by means of a survey, about the (non-pharmacological and pharmacological) preventive practices and (non-pharmacological and pharmacological) treatments in delirium used by qualified psychiatrists and those in training in Colombia.

Materials and methodsDesign, ethics and participantsA cross-sectional survey, approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana [Pontifical Bolivarian University] in Medellín, Colombia. As the study entailed no risks, the committee approved that requesting written informed consent was not necessary. The questionnaire header explained the objective and specified that participation was voluntary, that the survey was anonymous and that completing it amounted to agreeing to participate. The investigators are members of the Liaison Psychiatry Committee of the Asociación Colombiana de Psiquiatría [Colombian Psychiatry Association] (ACP). For circulating the survey and gathering statistics on the participants, we relied on the collaboration of the ACP, which neither sponsored nor participated in the design, analysis, the decision to publish or the preparation of the manuscript.

Of the 763 psychiatrists affiliated with the ACP in January 2019, 303 indicated that they worked at institutions that often saw patients with delirium, such as hospitals and clinics. Among those 303, 58 were specialists or training to be liaison psychiatrists. In addition, 231 psychiatry residents were registered in the ACP (this study assumed that residents see patients with delirium in the course of their training). In short, the target population consisted of the 303 psychiatrists and 231 residents who had the potential to see patients with the disorder.

Instrument and proceduresPreparation and description of the surveyThe study was designed in four stages. 1) To include a wide range of preventive and therapeutic interventions, not necessarily supported by high standards of evidence, two authors drafted a questionnaire taking into account the comprehensive reviews on prevention and treatment from the chapter on delirium by Trzepacz and Meagher in the Textbook of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences1 and from the chapter on the disorder by Maldonado in the book Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient.9 2) The other authors reviewed the text and made independent recommendations. The contents were consequently amended until all approved them. 3) One investigator prepared the formal diagramming/design of the questionnaire, which the others evaluated; it was amended accordingly and approved. 4) Finally, a pilot was done in which five psychiatrists filled in the survey, considering the comprehensibility of its language and contents. The opinion of the participants was favourable and therefore the 45-question survey was approved.

The questions are grouped into five sections: characterisation of the participants, non-pharmacological prevention, pharmacological prevention, non-pharmacological treatment and pharmacological treatment. Most questions were dichotomous to make them easier to answer and to reduce the effects of fatigue. Questions about indications for mechanical restraint, first and second pharmacological options in treatment, indications for benzodiazepines, duration of pharmacological treatment and dose ranges for antipsychotic agents in treatment were open-ended (participants could specify ranges as they liked). The authors agreed upon the way of grouping the data reported by the participants. Finally, several questions offered participants the option of elaborating on their responses. The annotations of those who used this option were reported.

Survey platform, distribution and window for data collectionSurveyMonkey (es.surveymonkey.com) was used, enabling the survey to be sent through a link in an e-mail. The survey could be opened on various devices (computers, mobile phones and tablets). SurveyMonkey reports the average time taken by survey participants. The platform has world-class data protection standards and it was determined in advance that it would not be possible to obtain the participants' e-mail addresses or any other identifying information.

The ACP distributed the survey exclusively to its members' e-mail addresses. The e-mail was sent on 18 October 2018, and the window for completing the survey remained open until 1 January 2019. According to the recommendations in the literature, to maximise the number of participants, a motivational e-mail was sent out prior to the survey.13

Data analysisThe data were analysed in SPSS 22. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check whether continuous variables had a normal distribution; those without a normal distribution were reported in terms of median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were presented in terms of frequencies and percentages. Although the study did not set out to analyse differences in responses among residents, psychiatrists and liaison psychiatrists (in training or qualified), exploratory analyses were performed wherever possible using Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Mann–Whitney U test for post hoc comparisons for continuous variables and with the chi-squared or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. The Bonferroni correction for multiple paired comparisons was used; hence, the level of significance (P value) was set at <.0167 (two-tailed). Unanswered questions are identified throughout the presentation of the results by including the “no response” option.

ResultsOne hundred and one questionnaires were answered: 64 (63.4%) by psychiatrists and 37 (36.6%) by residents. Twenty-four (37.5%) of the 64 psychiatrists were liaison psychiatrists, qualified or in training. The response rate among the 303 specialists who worked at institutions with potential for regular care of patients with delirium was 21.1%. Among the 231 residents, it was 16.0%; among the 58 liaison psychiatrists, qualified or in training, it was 41.4%. The majority of the participants were from Bogotá, followed by Medellín, Cali and Manizales. The mean time spent taking the survey was nine minutes and 24 s.

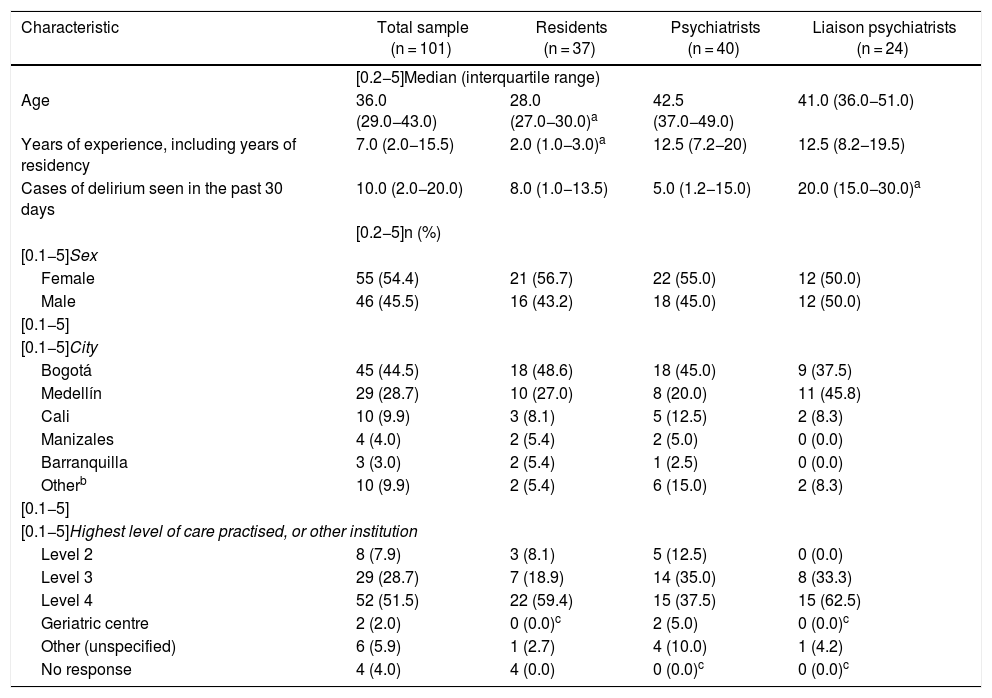

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the survey participants. As expected, the median age was younger and the median number of years of experience was lower among the residents than among the psychiatrists. In contrast, also as expected, the liaison psychiatrists saw more patients with delirium. There were no significant differences in the characteristics of the participants in the three groups.

Characteristics of 101 psychiatry residents, psychiatrists and liaison psychiatrists (qualified or in training) who practised in Colombia and answered the survey on approaches to delirium.

| Characteristic | Total sample (n = 101) | Residents (n = 37) | Psychiatrists (n = 40) | Liaison psychiatrists (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0.2−5]Median (interquartile range) | ||||

| Age | 36.0 (29.0−43.0) | 28.0 (27.0−30.0)a | 42.5 (37.0−49.0) | 41.0 (36.0−51.0) |

| Years of experience, including years of residency | 7.0 (2.0−15.5) | 2.0 (1.0−3.0)a | 12.5 (7.2−20) | 12.5 (8.2−19.5) |

| Cases of delirium seen in the past 30 days | 10.0 (2.0−20.0) | 8.0 (1.0−13.5) | 5.0 (1.2−15.0) | 20.0 (15.0−30.0)a |

| [0.2−5]n (%) | ||||

| [0.1−5]Sex | ||||

| Female | 55 (54.4) | 21 (56.7) | 22 (55.0) | 12 (50.0) |

| Male | 46 (45.5) | 16 (43.2) | 18 (45.0) | 12 (50.0) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]City | ||||

| Bogotá | 45 (44.5) | 18 (48.6) | 18 (45.0) | 9 (37.5) |

| Medellín | 29 (28.7) | 10 (27.0) | 8 (20.0) | 11 (45.8) |

| Cali | 10 (9.9) | 3 (8.1) | 5 (12.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| Manizales | 4 (4.0) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Barranquilla | 3 (3.0) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Otherb | 10 (9.9) | 2 (5.4) | 6 (15.0) | 2 (8.3) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]Highest level of care practised, or other institution | ||||

| Level 2 | 8 (7.9) | 3 (8.1) | 5 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Level 3 | 29 (28.7) | 7 (18.9) | 14 (35.0) | 8 (33.3) |

| Level 4 | 52 (51.5) | 22 (59.4) | 15 (37.5) | 15 (62.5) |

| Geriatric centre | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0)c | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0)c |

| Other (unspecified) | 6 (5.9) | 1 (2.7) | 4 (10.0) | 1 (4.2) |

| No response | 4 (4.0) | 4 (0.0) | 0 (0.0)c | 0 (0.0)c |

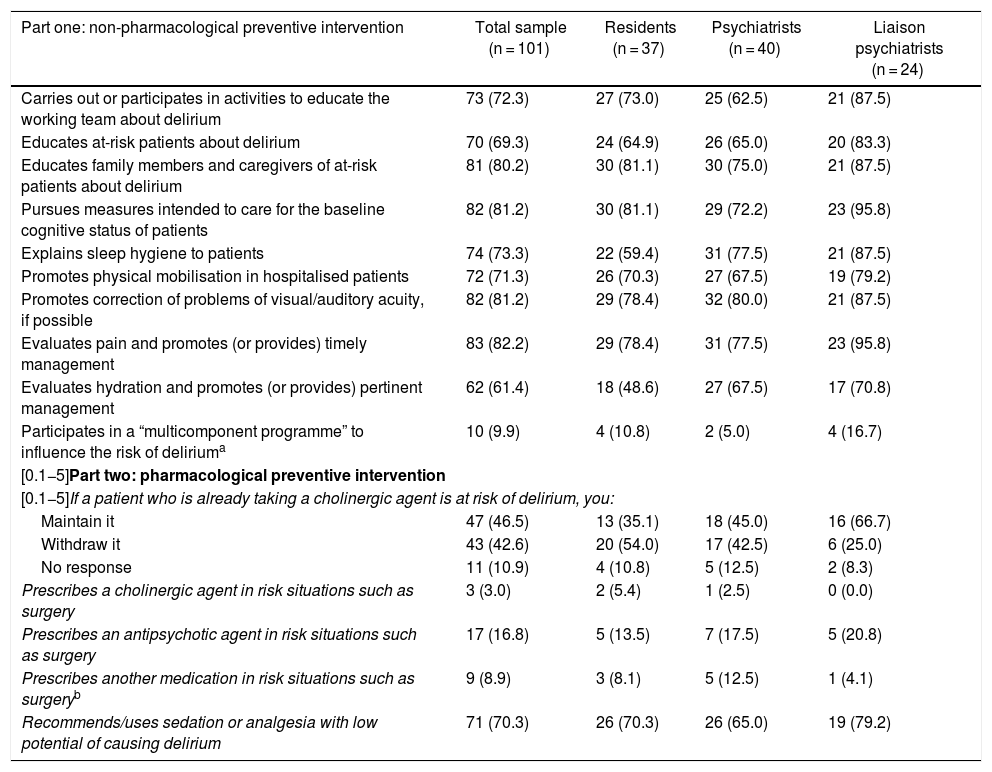

There were no statistically significant differences between the responses of the three groups of professionals in relation to preventive measures.

Practically all non-pharmacological actions — psychoeducation, baseline cognitive status care, correction of sensory problems, patient mobilisation, sleep hygiene and pain management — were made by the majority of the participants (70% or more). The number of clinicians who evaluated and intervened in the hydration of their patients was a little lower (61.4%). Only around one in 10 stated that they were part of any “multicomponent programme” to reduce delirium risk; of these, just six elaborated on their responses, and of those six, just one described a structured programme (called the Delirium Pathway) in which risk factors are identified, interventions are made and identification of the disorder is stressed. The first part of Table 2 shows the details of each non-pharmacological preventive measure about which the participants were asked.

Responses supplied by 101 psychiatry residents, psychiatrists and liaison psychiatrists (qualified or in training) in Colombia on interventions usually made for non-pharmacological and pharmacological prevention of delirium. Results are expressed in terms of frequency and percentage in parentheses. None of the paired comparisons between the three groups showed significant differences.

| Part one: non-pharmacological preventive intervention | Total sample (n = 101) | Residents (n = 37) | Psychiatrists (n = 40) | Liaison psychiatrists (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carries out or participates in activities to educate the working team about delirium | 73 (72.3) | 27 (73.0) | 25 (62.5) | 21 (87.5) |

| Educates at-risk patients about delirium | 70 (69.3) | 24 (64.9) | 26 (65.0) | 20 (83.3) |

| Educates family members and caregivers of at-risk patients about delirium | 81 (80.2) | 30 (81.1) | 30 (75.0) | 21 (87.5) |

| Pursues measures intended to care for the baseline cognitive status of patients | 82 (81.2) | 30 (81.1) | 29 (72.2) | 23 (95.8) |

| Explains sleep hygiene to patients | 74 (73.3) | 22 (59.4) | 31 (77.5) | 21 (87.5) |

| Promotes physical mobilisation in hospitalised patients | 72 (71.3) | 26 (70.3) | 27 (67.5) | 19 (79.2) |

| Promotes correction of problems of visual/auditory acuity, if possible | 82 (81.2) | 29 (78.4) | 32 (80.0) | 21 (87.5) |

| Evaluates pain and promotes (or provides) timely management | 83 (82.2) | 29 (78.4) | 31 (77.5) | 23 (95.8) |

| Evaluates hydration and promotes (or provides) pertinent management | 62 (61.4) | 18 (48.6) | 27 (67.5) | 17 (70.8) |

| Participates in a “multicomponent programme” to influence the risk of deliriuma | 10 (9.9) | 4 (10.8) | 2 (5.0) | 4 (16.7) |

| [0.1−5]Part two: pharmacological preventive intervention | ||||

| [0.1−5]If a patient who is already taking a cholinergic agent is at risk of delirium, you: | ||||

| Maintain it | 47 (46.5) | 13 (35.1) | 18 (45.0) | 16 (66.7) |

| Withdraw it | 43 (42.6) | 20 (54.0) | 17 (42.5) | 6 (25.0) |

| No response | 11 (10.9) | 4 (10.8) | 5 (12.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| Prescribes a cholinergic agent in risk situations such as surgery | 3 (3.0) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Prescribes an antipsychotic agent in risk situations such as surgery | 17 (16.8) | 5 (13.5) | 7 (17.5) | 5 (20.8) |

| Prescribes another medication in risk situations such as surgeryb | 9 (8.9) | 3 (8.1) | 5 (12.5) | 1 (4.1) |

| Recommends/uses sedation or analgesia with low potential of causing delirium | 71 (70.3) | 26 (70.3) | 26 (65.0) | 19 (79.2) |

Of the 10, six provided responses in relation to this type of preventive programme: four specified some sort of interdisciplinary work without clarifying the nature of the specific measures of non-pharmacological prevention, one indicated that they followed the indications on prevention in the HELP programme and one indicated that their institution had the programme called the Delirium Pathway (for evaluation and intervention in risk factors and timely standardised evaluation and management of delirium).

Prescription of antipsychotic agents, cholinergic agents (such as donepezil and rivastigmine) and other medications for preventive purposes was always less than 20%. In cases of risk of delirium, virtually half those surveyed maintained a cholinergic agent that the patient was already taking (see details in part two of Table 2).

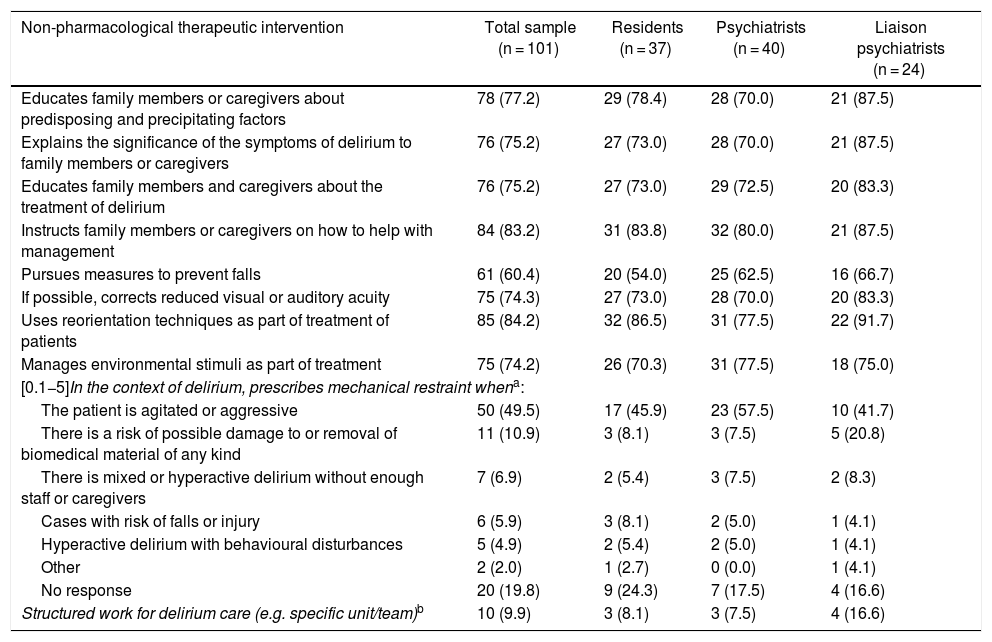

Non-pharmacological treatmentTable 3 specifies non-pharmacological treatment measures, in which there were no significant differences between groups. All the psychoeducation activities were practised by more than 75%. The percentage of professionals who took steps to reduce the risk of falls in their patients with delirium was lower (60.4%). Routine correction of sensory difficulties, management of environmental stimuli and reorientation actions were practised by 75% or more; notably, reorientation was practised by 84.2%.

Responses supplied by 101 psychiatry residents, psychiatrists and liaison psychiatrists (qualified or in training) in Colombia on non-pharmacological interventions usually made in the treatment of patients with delirium. Results are expressed in terms of frequency and percentage in parentheses. None of the paired comparisons between the three groups showed significant differences.

| Non-pharmacological therapeutic intervention | Total sample (n = 101) | Residents (n = 37) | Psychiatrists (n = 40) | Liaison psychiatrists (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educates family members or caregivers about predisposing and precipitating factors | 78 (77.2) | 29 (78.4) | 28 (70.0) | 21 (87.5) |

| Explains the significance of the symptoms of delirium to family members or caregivers | 76 (75.2) | 27 (73.0) | 28 (70.0) | 21 (87.5) |

| Educates family members and caregivers about the treatment of delirium | 76 (75.2) | 27 (73.0) | 29 (72.5) | 20 (83.3) |

| Instructs family members or caregivers on how to help with management | 84 (83.2) | 31 (83.8) | 32 (80.0) | 21 (87.5) |

| Pursues measures to prevent falls | 61 (60.4) | 20 (54.0) | 25 (62.5) | 16 (66.7) |

| If possible, corrects reduced visual or auditory acuity | 75 (74.3) | 27 (73.0) | 28 (70.0) | 20 (83.3) |

| Uses reorientation techniques as part of treatment of patients | 85 (84.2) | 32 (86.5) | 31 (77.5) | 22 (91.7) |

| Manages environmental stimuli as part of treatment | 75 (74.2) | 26 (70.3) | 31 (77.5) | 18 (75.0) |

| [0.1−5]In the context of delirium, prescribes mechanical restraint whena: | ||||

| The patient is agitated or aggressive | 50 (49.5) | 17 (45.9) | 23 (57.5) | 10 (41.7) |

| There is a risk of possible damage to or removal of biomedical material of any kind | 11 (10.9) | 3 (8.1) | 3 (7.5) | 5 (20.8) |

| There is mixed or hyperactive delirium without enough staff or caregivers | 7 (6.9) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (7.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| Cases with risk of falls or injury | 6 (5.9) | 3 (8.1) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (4.1) |

| Hyperactive delirium with behavioural disturbances | 5 (4.9) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (4.1) |

| Other | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.1) |

| No response | 20 (19.8) | 9 (24.3) | 7 (17.5) | 4 (16.6) |

| Structured work for delirium care (e.g. specific unit/team)b | 10 (9.9) | 3 (8.1) | 3 (7.5) | 4 (16.6) |

Concerning indications for mechanical restraint, 60.4% used it when a patient was agitated/aggressive or when there was a risk of damage to/removal of biomedical material. All other indications had a rate lower than 7% and, strikingly, were generally associated with increased motor activity or a lack of staff or companions supervising the patient's behaviour (Table 3).

Although 9.9% indicated that their work was structured for focused care of delirium, none really explained how they went about organised work through any type of specific care unit or team for treatment.

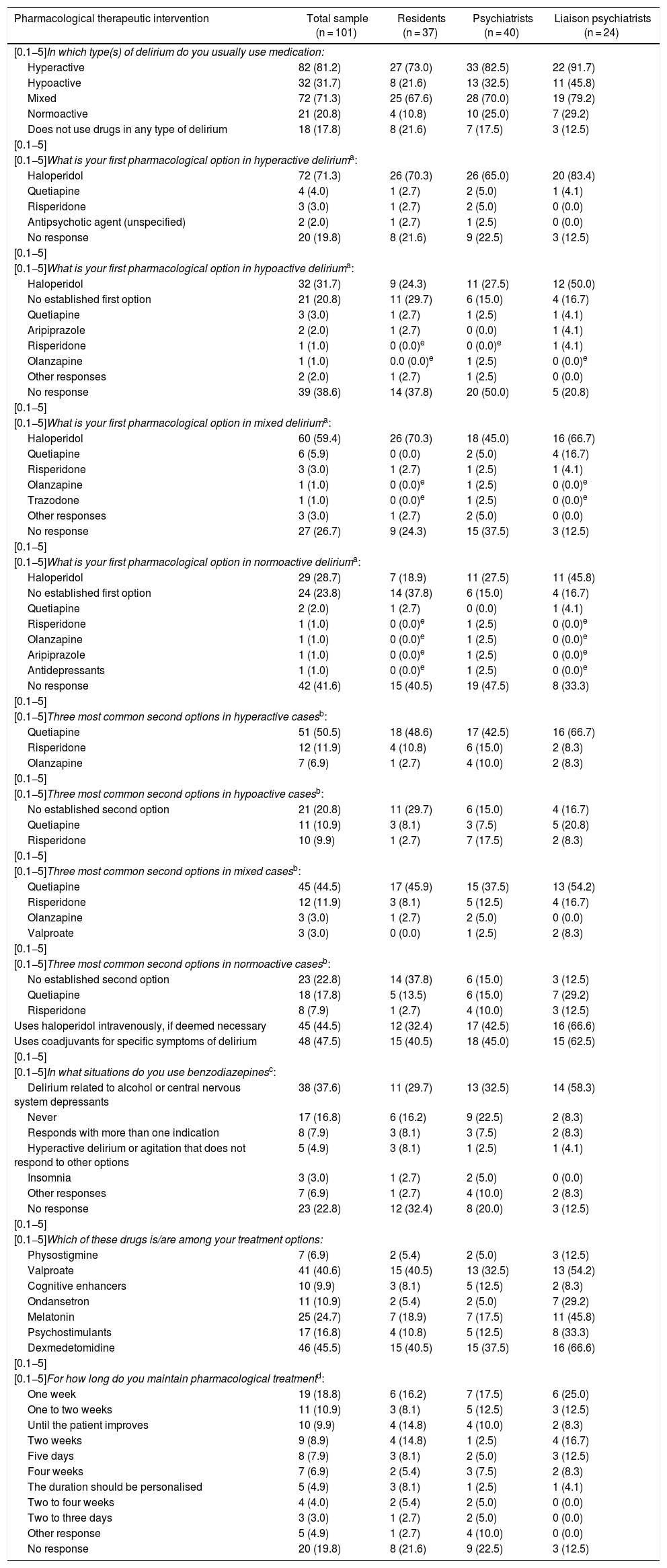

Pharmacological treatmentTable 4 reports the percentage of patients treated with medications by motor subtype of delirium. While more than 70% of hyperactive or mixed cases were prescribed a drug, less than 32% of hypoactive or normoactive cases received any. Notably, 18 (17.8%) physicians did not prescribe medication to treat delirium, and no clear trend was seen in prescription duration.

Responses supplied by 101 psychiatry residents, psychiatrists and liaison psychiatrists (qualified or in training) in Colombia on pharmacological interventions usually made in the management of patients with an established diagnosis of delirium. Results are expressed in terms of frequency and percentage in parentheses. None of the paired comparisons between the three groups showed significant differences.

| Pharmacological therapeutic intervention | Total sample (n = 101) | Residents (n = 37) | Psychiatrists (n = 40) | Liaison psychiatrists (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0.1−5]In which type(s) of delirium do you usually use medication: | ||||

| Hyperactive | 82 (81.2) | 27 (73.0) | 33 (82.5) | 22 (91.7) |

| Hypoactive | 32 (31.7) | 8 (21.6) | 13 (32.5) | 11 (45.8) |

| Mixed | 72 (71.3) | 25 (67.6) | 28 (70.0) | 19 (79.2) |

| Normoactive | 21 (20.8) | 4 (10.8) | 10 (25.0) | 7 (29.2) |

| Does not use drugs in any type of delirium | 18 (17.8) | 8 (21.6) | 7 (17.5) | 3 (12.5) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]What is your first pharmacological option in hyperactive deliriuma: | ||||

| Haloperidol | 72 (71.3) | 26 (70.3) | 26 (65.0) | 20 (83.4) |

| Quetiapine | 4 (4.0) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (4.1) |

| Risperidone | 3 (3.0) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Antipsychotic agent (unspecified) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| No response | 20 (19.8) | 8 (21.6) | 9 (22.5) | 3 (12.5) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]What is your first pharmacological option in hypoactive deliriuma: | ||||

| Haloperidol | 32 (31.7) | 9 (24.3) | 11 (27.5) | 12 (50.0) |

| No established first option | 21 (20.8) | 11 (29.7) | 6 (15.0) | 4 (16.7) |

| Quetiapine | 3 (3.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.1) |

| Aripiprazole | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.1) |

| Risperidone | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0)e | 0 (0.0)e | 1 (4.1) |

| Olanzapine | 1 (1.0) | 0.0 (0.0)e | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0)e |

| Other responses | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| No response | 39 (38.6) | 14 (37.8) | 20 (50.0) | 5 (20.8) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]What is your first pharmacological option in mixed deliriuma: | ||||

| Haloperidol | 60 (59.4) | 26 (70.3) | 18 (45.0) | 16 (66.7) |

| Quetiapine | 6 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.0) | 4 (16.7) |

| Risperidone | 3 (3.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.1) |

| Olanzapine | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0)e | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0)e |

| Trazodone | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0)e | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0)e |

| Other responses | 3 (3.0) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No response | 27 (26.7) | 9 (24.3) | 15 (37.5) | 3 (12.5) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]What is your first pharmacological option in normoactive deliriuma: | ||||

| Haloperidol | 29 (28.7) | 7 (18.9) | 11 (27.5) | 11 (45.8) |

| No established first option | 24 (23.8) | 14 (37.8) | 6 (15.0) | 4 (16.7) |

| Quetiapine | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.1) |

| Risperidone | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0)e | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0)e |

| Olanzapine | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0)e | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0)e |

| Aripiprazole | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0)e | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0)e |

| Antidepressants | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0)e | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0)e |

| No response | 42 (41.6) | 15 (40.5) | 19 (47.5) | 8 (33.3) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]Three most common second options in hyperactive casesb: | ||||

| Quetiapine | 51 (50.5) | 18 (48.6) | 17 (42.5) | 16 (66.7) |

| Risperidone | 12 (11.9) | 4 (10.8) | 6 (15.0) | 2 (8.3) |

| Olanzapine | 7 (6.9) | 1 (2.7) | 4 (10.0) | 2 (8.3) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]Three most common second options in hypoactive casesb: | ||||

| No established second option | 21 (20.8) | 11 (29.7) | 6 (15.0) | 4 (16.7) |

| Quetiapine | 11 (10.9) | 3 (8.1) | 3 (7.5) | 5 (20.8) |

| Risperidone | 10 (9.9) | 1 (2.7) | 7 (17.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]Three most common second options in mixed casesb: | ||||

| Quetiapine | 45 (44.5) | 17 (45.9) | 15 (37.5) | 13 (54.2) |

| Risperidone | 12 (11.9) | 3 (8.1) | 5 (12.5) | 4 (16.7) |

| Olanzapine | 3 (3.0) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Valproate | 3 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]Three most common second options in normoactive casesb: | ||||

| No established second option | 23 (22.8) | 14 (37.8) | 6 (15.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| Quetiapine | 18 (17.8) | 5 (13.5) | 6 (15.0) | 7 (29.2) |

| Risperidone | 8 (7.9) | 1 (2.7) | 4 (10.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| Uses haloperidol intravenously, if deemed necessary | 45 (44.5) | 12 (32.4) | 17 (42.5) | 16 (66.6) |

| Uses coadjuvants for specific symptoms of delirium | 48 (47.5) | 15 (40.5) | 18 (45.0) | 15 (62.5) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]In what situations do you use benzodiazepinesc: | ||||

| Delirium related to alcohol or central nervous system depressants | 38 (37.6) | 11 (29.7) | 13 (32.5) | 14 (58.3) |

| Never | 17 (16.8) | 6 (16.2) | 9 (22.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| Responds with more than one indication | 8 (7.9) | 3 (8.1) | 3 (7.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| Hyperactive delirium or agitation that does not respond to other options | 5 (4.9) | 3 (8.1) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.1) |

| Insomnia | 3 (3.0) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other responses | 7 (6.9) | 1 (2.7) | 4 (10.0) | 2 (8.3) |

| No response | 23 (22.8) | 12 (32.4) | 8 (20.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]Which of these drugs is/are among your treatment options: | ||||

| Physostigmine | 7 (6.9) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| Valproate | 41 (40.6) | 15 (40.5) | 13 (32.5) | 13 (54.2) |

| Cognitive enhancers | 10 (9.9) | 3 (8.1) | 5 (12.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| Ondansetron | 11 (10.9) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.0) | 7 (29.2) |

| Melatonin | 25 (24.7) | 7 (18.9) | 7 (17.5) | 11 (45.8) |

| Psychostimulants | 17 (16.8) | 4 (10.8) | 5 (12.5) | 8 (33.3) |

| Dexmedetomidine | 46 (45.5) | 15 (40.5) | 15 (37.5) | 16 (66.6) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]For how long do you maintain pharmacological treatmentd: | ||||

| One week | 19 (18.8) | 6 (16.2) | 7 (17.5) | 6 (25.0) |

| One to two weeks | 11 (10.9) | 3 (8.1) | 5 (12.5) | 3 (12.5) |

| Until the patient improves | 10 (9.9) | 4 (14.8) | 4 (10.0) | 2 (8.3) |

| Two weeks | 9 (8.9) | 4 (14.8) | 1 (2.5) | 4 (16.7) |

| Five days | 8 (7.9) | 3 (8.1) | 2 (5.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| Four weeks | 7 (6.9) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (7.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| The duration should be personalised | 5 (4.9) | 3 (8.1) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.1) |

| Two to four weeks | 4 (4.0) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Two to three days | 3 (3.0) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other response | 5 (4.9) | 1 (2.7) | 4 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No response | 20 (19.8) | 8 (21.6) | 9 (22.5) | 3 (12.5) |

Open-ended question. Of 20 who did not respond in the hyperactive type, 18 (90%) did not usually use medication in these cases. Of 39 who did not respond in the hypoactive type, 38 (97.4%) did not usually use medication in this type. Of 27 who did not answer in the mixed type, 21 (77.8%) did not usually use medication in this type. None of those who did not respond in the normoactive type medicated this type.

Open-ended question, regrouped by the investigators. The “other response” option included: context of palliative care, withdrawal/risk of withdrawal (without specifying substances), hyperactive delirium/various degrees of agitation. Of the 23 who did not respond, 18 (78.3%) did not treat delirium with drugs.

The first pharmacological option in any motor subtype is haloperidol (more in cases with increased motor activity). Nearly half used it intravenously if necessary. Interestingly, around 20% of the participants did not have an established first option for hypoactive or normoactive cases. The second most common medication as a first option, although in much lower percentages, was quetiapine. From there, there was no consensus, although three antipsychotic agents came up repeatedly: risperidone, olanzapine and aripiprazole. The drug most commonly reported as a second option in any motor subtype was always quetiapine, although in cases with normal or reduced motor activity it was surpassed by statements of having no established second option. Though less common and with less agreement, risperidone and olanzapine were other second options. In addition to antipsychotic agents, the most common treatment options were valproate and dexmedetomidine (Table 4).

Nearly half the clinicians used coadjuvants. Concerning benzodiazepines, rates of use for indications other than delirium related to central nervous system depressants were always less than 10% (Table 4).

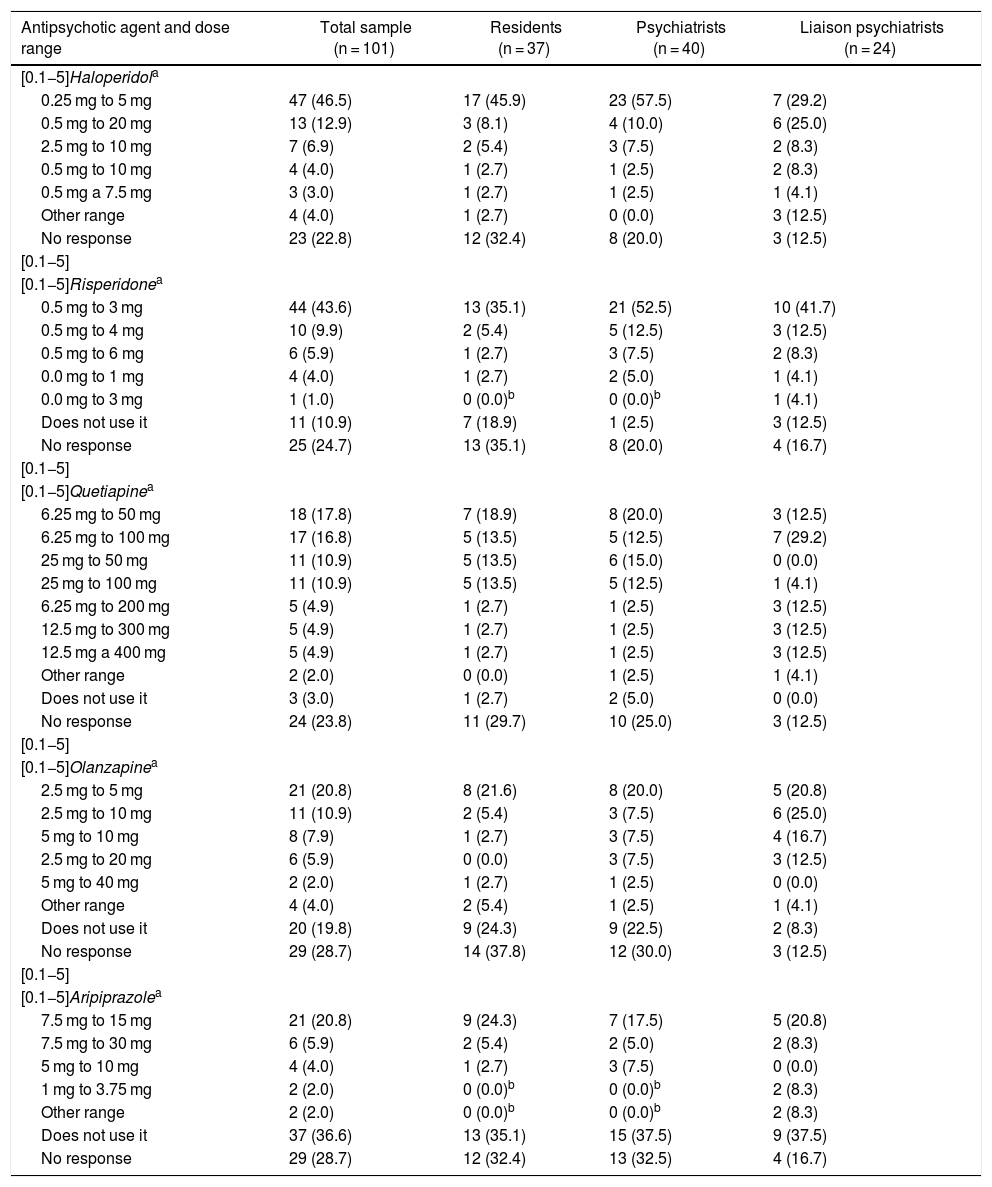

Table 5 shows the dose ranges for haloperidol, risperidone, quetiapine, olanzapine and aripiprazole used by the participants. While none of the ranges achieved at least 50% agreement, the majority of the participants preferred relatively low doses, e.g. between 0.25 mg as a minimum and 5 mg as a maximum daily dose of haloperidol or from 6.25 mg as a minimum to 50 mg or 100 mg as a maximum daily dose of quetiapine. Ranges tended to be somewhat higher for aripiprazole.

Frequencies (percentages) for the dose range per day of antipsychotic agents used by 101 psychiatry residents, psychiatrists and liaison psychiatrists (qualified or in training) in Colombia. None of the paired comparisons between the three groups showed significant differences.

| Antipsychotic agent and dose range | Total sample (n = 101) | Residents (n = 37) | Psychiatrists (n = 40) | Liaison psychiatrists (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0.1−5]Haloperidola | ||||

| 0.25 mg to 5 mg | 47 (46.5) | 17 (45.9) | 23 (57.5) | 7 (29.2) |

| 0.5 mg to 20 mg | 13 (12.9) | 3 (8.1) | 4 (10.0) | 6 (25.0) |

| 2.5 mg to 10 mg | 7 (6.9) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (7.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| 0.5 mg to 10 mg | 4 (4.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| 0.5 mg a 7.5 mg | 3 (3.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.1) |

| Other range | 4 (4.0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| No response | 23 (22.8) | 12 (32.4) | 8 (20.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]Risperidonea | ||||

| 0.5 mg to 3 mg | 44 (43.6) | 13 (35.1) | 21 (52.5) | 10 (41.7) |

| 0.5 mg to 4 mg | 10 (9.9) | 2 (5.4) | 5 (12.5) | 3 (12.5) |

| 0.5 mg to 6 mg | 6 (5.9) | 1 (2.7) | 3 (7.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| 0.0 mg to 1 mg | 4 (4.0) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (4.1) |

| 0.0 mg to 3 mg | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0)b | 0 (0.0)b | 1 (4.1) |

| Does not use it | 11 (10.9) | 7 (18.9) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (12.5) |

| No response | 25 (24.7) | 13 (35.1) | 8 (20.0) | 4 (16.7) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]Quetiapinea | ||||

| 6.25 mg to 50 mg | 18 (17.8) | 7 (18.9) | 8 (20.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| 6.25 mg to 100 mg | 17 (16.8) | 5 (13.5) | 5 (12.5) | 7 (29.2) |

| 25 mg to 50 mg | 11 (10.9) | 5 (13.5) | 6 (15.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 25 mg to 100 mg | 11 (10.9) | 5 (13.5) | 5 (12.5) | 1 (4.1) |

| 6.25 mg to 200 mg | 5 (4.9) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (12.5) |

| 12.5 mg to 300 mg | 5 (4.9) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (12.5) |

| 12.5 mg a 400 mg | 5 (4.9) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (12.5) |

| Other range | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.1) |

| Does not use it | 3 (3.0) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No response | 24 (23.8) | 11 (29.7) | 10 (25.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]Olanzapinea | ||||

| 2.5 mg to 5 mg | 21 (20.8) | 8 (21.6) | 8 (20.0) | 5 (20.8) |

| 2.5 mg to 10 mg | 11 (10.9) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (7.5) | 6 (25.0) |

| 5 mg to 10 mg | 8 (7.9) | 1 (2.7) | 3 (7.5) | 4 (16.7) |

| 2.5 mg to 20 mg | 6 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.5) | 3 (12.5) |

| 5 mg to 40 mg | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other range | 4 (4.0) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.1) |

| Does not use it | 20 (19.8) | 9 (24.3) | 9 (22.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| No response | 29 (28.7) | 14 (37.8) | 12 (30.0) | 3 (12.5) |

| [0.1−5] | ||||

| [0.1−5]Aripiprazolea | ||||

| 7.5 mg to 15 mg | 21 (20.8) | 9 (24.3) | 7 (17.5) | 5 (20.8) |

| 7.5 mg to 30 mg | 6 (5.9) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.0) | 2 (8.3) |

| 5 mg to 10 mg | 4 (4.0) | 1 (2.7) | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| 1 mg to 3.75 mg | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0)b | 0 (0.0)b | 2 (8.3) |

| Other range | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0)b | 0 (0.0)b | 2 (8.3) |

| Does not use it | 37 (36.6) | 13 (35.1) | 15 (37.5) | 9 (37.5) |

| No response | 29 (28.7) | 12 (32.4) | 13 (32.5) | 4 (16.7) |

Although a significant percentage of questions about medication were not answered (see “No response” in Tables 4 and 5), it is important to note that between 62.1% and 100% of the participants who left any unanswered did not use drugs in the motor subtype of delirium asked about or did not use any medications when asked about the disorder in general (see the corresponding table footers). The tables show either that there were no statistically significant differences between the responses of the three groups, or that, in some cases, responses equal to zero (0) did not enable comparisons in relation to pharmacological treatment.

Finally, regarding follow-up of patients after delirium, 79 (78.2%) of survey participants believed that there should be an evaluation by psychiatry when the condition is referred.

DiscussionThe keys to managing delirium undoubtedly lie in identifying and treating its causes. Beyond this, evidence on all other preventive and therapeutic measures is scant or contradictory. Knowledge of the preventive and therapeutic actions taken by experts is important in this context. The majority of the survey participants in this study practised non-pharmacological prevention and treatment measures on their own, i.e. not within a structured care system. In general, the survey participants did not prescribe drugs on a preventive basis, and with regard to pharmacological treatment, there was a clear tendency to medicate hyperactive and mixed cases, but not hypoactive cases. The answers supplied by the three groups of professionals to the survey were comparable.

Non-pharmacological prevention and treatmentStructured, multicomponent programmes for non-pharmacological prevention have been proposed. The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), focused on baseline cognitive function care, sleep hygiene, appropriate mobilisation and suitable hydration, is quite well known.11 Another system, the Delirium Pathway, includes prevention and treatment aspects, as it combines work on risk factors with timely diagnosis and intervention.14

Structured active interconsultation programmes have an impact on the onset of delirium, provided that they include education (of the treating team, patients or the companions) and intervention for sensory deficits and symptoms such as pain.15 It is not known for certain whether these strategies manage to reduce the incidence of the syndrome or, in the event of its onset, the severity and duration of its symptoms; whether some of their components are more useful than others is also unclear.16

The above-mentioned preventive programmes are difficult to implement due to poor adherence on the part of care teams or for administrative reasons. Similar difficulties pose obstacles to implementing treatment programmes (delirium units and delirium intervention teams) that maximise non-pharmacological aspects such as education, environmental modifications, reorientation techniques or suitable hydration.17

The fact that the majority of the survey participants took non-pharmacological preventive and treatment actions on their own indicated good knowledge of factors that increase the risk and worsen the course of delirium. The contrast to the lack of structured institutional programmes was striking. That is to say, the involvement of the professionals was greater than that of the institutions, even though decreasing the prevalence of delirium is a healthcare quality indicator.18 In line with this, experts in each country must establish prevention and treatment programmes suited to their administrative realities and particular healthcare systems. Adherence to the programmes and the effectiveness of their specific components must be regularly evaluated to make the pertinent changes.

Mechanical containment merits special mention. This is used in treatment (never in prevention) only when behavioural disturbances endanger the safety of the patient or of nearby people. It should always include regular evaluations of the patient's condition and of the persistence of the indication.19 The consensus found on its use in cases of risk to the patient or to others, once the diagnosis has been made, was indicative of good care quality.

Pharmacological preventionAlthough multiple studies on antipsychotic agents such as haloperidol, risperidone and olanzapine have demonstrated beneficial effects in prophylaxis, there are disagreements as to what these effects are. While a meta-analysis by Teslyar et al. indicated that they reduce incidence,20 others have reported that they decrease episode severity or duration.21 The studies mentioned used varying antipsychotic agents, doses and protocols. To disagreements about which is the most effective, the most suitable regimen of administration or the effects on prevention, is added the need to identify patients at high risk of delirium and to implement routine psychiatric evaluation protocols in specific populations. This may explain why less than 20% of survey participants used this strategy.

Cholinergic agents such as donepezil and rivastigmine appear to be a logical choice in prevention, especially when used to treat dementia, which is the most significant predisposing factor for delirium.22 Despite this reasoning, a placebo-controlled trial on prevention with rivastigmine was suspended due to the trend towards greater mortality in the medication group.23 Other studies have not supported the use of these drugs, although there have been promising reports.24 With the current information, it is too soon to conclude that cholinergic agents are not useful in prevention, since many studies have had an open-label design, few participants, brief administration periods, or low doses. The behaviour of our survey participants was consistent with this uncertainty; virtually half suspended these drugs and the other half maintained them if patients were already taking them. Less than 5% prescribed them as a preventive measure.

Pharmacological prevention also includes rationalisation of medication regimens for baseline health conditions. This is particularly important when the drugs act on receptors involved in the pathophysiology of delirium (such as cholinergic agents, dopaminergic agents, opiates and GABAergic agents), as occurs with many sedatives and analgesics. In this regard, decisions as to which sedative or analgesic is best and at what dose should be personalised. For example, Maldonado et al. (2009)25 found that dexmedetomidine, a selective α2 agonist with sedative and analgesic activity, “saved on” episodes of delirium; their findings have been corroborated in double-blind, randomised, controlled evaluation.26 The majority (seven out of every 10 survey participants) took into account the “deliriogenic” potential of sedation and analgesia when deciding with their team on the best management of their patients.

Pharmacological treatmentAntipsychotic agentsAlthough some studies have supported the use of antipsychotic agents in treatment, others have not; furthermore, there is fear of their cardiovascular and metabolic effects and uncertainty about the reasons for their use: a sedative effect in cases of increased motor activity or a specific action on the disorder.10 The responses of eight in 10 survey participants indicated that the majority were in favour of using antipsychotic agents (with haloperidol as a first option) and that many used them to manage increased motor activity in hyperactive and mixed cases, whereas just two or three out of every 10 prescribed them in hypoactive and normoactive cases.

A network meta-analysis by Wu et al. (2019), which assessed all the drugs studied in this context, reported that haloperidol, quetiapine and olanzapine, analysed individually, were better than placebo or control, and did not find that pharmacological interventions increased mortality.27 Regarding the specific effects of antipsychotic agents on the disorder, they aid in restoring the balance between dopamine and acetylcholine, altered in delirium, which is contrary to the belief that its effects are sedative only.28 More extensive studies with suitable instruments and assessment of status markers, such as electrophysiological markers, are needed to determine the effects of antipsychotic agents on delirium and, equally importantly, on duration of hospitalisation, morbidity and mortality during admission, and what happens to patients after discharge.

The survey participants' choice of an antipsychotic agent as a first pharmacological option matched that of other experts asked in Europe.29 Furthermore, the most common first option always being haloperidol was consistent with the 2004 update of the 1999 American Psychiatric Association guidelines30 and with the 2019 update of the 2010 guidelines of the British National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).31 Quetiapine, either as the second most common drug among the first options or as the most common drug among second options, was backed by the above-mentioned network meta-analysis, in which this medication, with which there are fewer years of experience than haloperidol, equalled it in effectiveness.27

One of the advantages of haloperidol is the years of experience with its parenteral presentation. Although approved only for intramuscular use, nearly half the survey participants used it intravenously if needed. This practice is supported by the literature, has the advantage of being less traumatic for the confused patient, and reduces the risk of extrapyramidal effects. On the other hand, it increases the risk of cardiovascular complications in predisposed individuals; therefore, the baseline status of this risk must be evaluated and weighed against the benefits of quickly managing delirium and having electrocardiographic control.32

In general, the experts in Colombia agree with those in other countries in recommending a small lower limit for antipsychotic agent dose ranges. Furthermore, the survey participants recommended ranges similar to those of trials on those most commonly used, which are: haloperidol 0.25–10 mg, quetiapine 12.5–300 mg, risperidone 0.5–3 mg and olanzapine 1.25–20 mg.29 This was in line with the recommendations on the use of low initial doses in geriatric patients, those with comorbidities and those with cardiovascular risk.33 The exception was aripiprazole, for which the majority of those who used it indicated the relatively high minimum dose of 7.5 mg. It is difficult to make recommendations about the minimum effective dose of aripiprazole, since, on the one hand, tit has little empirical support in delirium and, on the other hand, it is relatively safe from a cardiovascular and metabolic point of view.34

Other medicationsOther drugs have been tested in small-scale trials, in non-replicated studies or in case series. With this history of scant empirical information, the recognition of other options, either as coadjuvants or as a choice when antipsychotics are contraindicated or there is no response to these, derives both from knowledge of the literature and from experience. Strikingly, both valproate (neuroprotective) and melatonin (which along with its receptor agonists regulates the circadian rhythm) were among those most mentioned as other therapeutic options, as interest in these is growing.35,36 It is also interesting that dexmedetomidine was the most commonly selected treatment option among these. Although it is better known for “saving on” delirium, it could be useful as rescue therapy in hyperactive cases.37

Although adding benzodiazepines to treatment relieves agitation and the lack of night-time sleep, their deleterious effect on cognition, sleep architecture and motor function, as well as their anticholinergic action, causes them to worsen the prognosis. This means that their only indication is in withdrawal from nervous system depressants.38 Most of those who responded indicated that they did not use them in delirium or used them in this context of withdrawal. The fact that less than 5% used them as rescue therapy in hyperactive/agitated cases or in cases of difficulty falling asleep was a positive finding.

Duration of pharmacological treatment and clinical follow-upResponses on duration of medication maintenance ranged from two days to four weeks, with no defined preference. The literature does not clarify matters much. Some experts recommend gradually reducing the dose once clinical management is achieved and re-evaluating for recurrence of symptoms (e.g. reducing by 50% every 24 h) to decrease the risk of adverse effects; others believe that one week is a suitable maintenance period to ensure that cases with persistent, difficult-to-detect symptoms do not cease to receive treatment.39

Encouragingly, nearly eight in 10 survey participants considered psychiatric follow-up necessary after an episode of delirium. The disorder has serious psychological and psychiatric consequences that should be borne in mind, such as patients' fear of further episodes leading to silent cases, anxiety due to not remembering what happened, various degrees of post-traumatic symptoms and depression, persistent cognitive and functional impairment or its worsening when it is pre-existing.40

LimitationsComparisons between the characteristics and practices of the psychiatry residents, psychiatrists and liaison psychiatrists could indicate that training in Colombia is good, since there were no differences between them or between them and the literature reviewed. However, the results of the comparisons in this first study on the subject were merely exploratory. The numerical trend among the liaison psychiatrists towards using some non-pharmacological prevention and treatment measures more often (Tables 2 and 3) as well as, to a lesser extent, some pharmacological treatment interventions (Table 4) points to a need for studies that measure the impact of training on the approach to specific disorders. The data reported here for each of the participating groups could be useful in calculating the sample size for surveys on this topic in the context of delirium.

Although there was a wide range of years of experience among the survey participants, and both their cities of origin and the characteristics of their places of work were diverse, the response rate was low. This is a common problem in surveys of physicians. Nevertheless, this sort of investigation is important when the evidence is not convincing, especially when research on physicians who are “non-responders” recommends conducting such surveys, since the bias attributed to non-responders does not have as much of an impact as was thought.13 In line with this, the participants' practices were generally comparable to those of experts in other countries and consistent with the literature.

From another perspective, the information available in the ACP on the activities of the affiliated physicians was limited. The number of professionals who regularly see patients with delirium may be lower than that identified in this study. As surveys are useful for gaining insight into healthcare, teaching, and research practices, awareness-raising campaigns are needed among ACP members on the importance of participating. The information recorded on ACP members must also be expanded.

ConclusionsThe agreement between the survey participants and other experts around the world indicated that their knowledge was sufficient and their approach to delirium suitable. The participants routinely pursued non-pharmacological measures of prevention and treatment. On the other hand, they did not prescribe drugs on a preventive basis and tended to medicate those cases with increased motor activity.

Practically all the actions were individual initiatives, highlighting the need for health institutions in Colombia to commit to preventing and treating delirium, especially when its prevalence and its consequences are indicators of healthcare quality.

Sources of fundingNone.

The results of this study were presented in a lecture as part of a symposium on delirium at the 63rd Colombian Psychiatry Conference in Barranquilla, Colombia, in 2019.

Conflicts of interestGabriel Fernando Oviedo Lugo has sat on Janssen's advisory board. Liliana Patarroyo Rodriguez has been a speaker for Lundbeck. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Franco JG, Oviedo Lugo GF, Patarroyo Rodriguez L, Bernal Miranda J, Carlos Molano J, Rojas Moreno M, et al. Encuesta a psiquiatras y residentes de psiquiatría en Colombia sobre sus prácticas preventivas y terapéuticas del delirium. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:260–272.