Traumatic events and violence are widespread public health problems. They do not have limits related to age, sex or socioeconomic level. The prevalence of mental disorders and sociodemographic characteristics were compared in the context of traumatic events and types of violence in the general population.

Materials and methodsObservational prevalence study with a secondary information source, in the general population aged 13–65 years, selected at random. The interview was conducted using the Compositum International Diagnosis Interview which generates psychiatric diagnoses according to the DSM-IV. The variables included were traumatic events grouped into five categories: related to armed conflict, sexual violence, interfamily violence, other types of violence, traumas and some mental disorders. The prevalence of mental disorders was compared in the five categories of traumatic events. Statistical significance was defined as a p value of <0.05.

ResultsSexual and interfamily violence were more prevalent in women (p < 0.05). In those under age 13, major depression related to armed conflict had a prevalence of 48.3%, with a significant difference from the other trauma groups (p = 0.015). All prevalences for childhood-onset disorders showed significantly different prevalences compared with the group for violence related to armed conflict (p < 0.05) and suicidal ideation was higher in the sexual violence group (p = 0.006).

DiscussionHigh prevalences of mental disorders were found in people who had been exposed to traumatic events and violence. In those who experienced traumatic events related to armed conflict and sexual violence, higher prevalences of certain mental disorders were detected.

Los eventos traumáticos y la violencia son problemas de salud pública generalizados. No tienen límites de edad, sexo o nivel socioeconómico. Se comparó la prevalencia de trastornos mentales y las características sociodemográficas desde la perspectiva de eventos traumáticos y tipos de violencia en población general.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional de prevalencia, con fuente de información secundaria, en población general de 13 a 65 años, seleccionados al azar. La entrevista se realizó con la Compositum International Diagnosis Interview, la cual genera diagnósticos psiquiátricos según el DSMIV. Las variables incluidas fueron: eventos traumáticos agrupados en 5 categorías: relacionadas con el conflicto armado, violencia sexual, violencia intrafamiliar, otras violencias, traumas y algunos trastornos mentales. Se compararon las prevalencias de trastornos mentales en las 5 categorías de eventos traumáticos. Se definió la significación estadística en p < 0,05.

ResultadosLa violencia sexual e intrafamiliar fueron más prevalentes en mujeres (p < 0,05). En los menores de 13 años, la depresión mayor relacionada con el conflicto armado tuvo una prevalencia del 48,3%, con diferencia significativa con los demás grupos de traumas (p = 0,015). Todas las prevalencias de los trastornos de inicio en la infancia mostraron diferencias significas en el grupo de violencia relacionada con el conflicto armado (p < 0,05), y la ideación suicida fue mayor en el grupo de violencia sexual (p = 0,006).

DiscusiónSe encontraron altas prevalencias de trastornos mentales en personas con exposición en la vida a eventos traumáticos y violencia. En quienes experimentaron eventos traumáticos relacionados con el conflicto armado y la violencia sexual, se encontraron las más altas prevalencias de algunos trastornos mentales.

Trauma and violence are widespread, harmful and costly public health problems. They know no limit in terms of age, gender, socio-economic level, race, ethnic background or sexual orientation. Trauma is a common experience among adults and children in populations all over the world, and is particularly common in the lives of people with mental and substance use disorders. For this reason, trauma must be addressed as an important part of medical history in comprehensive healthcare and in recovery and rehabilitation processes.1

Exposure to traumatic events varies extensively depending on the contexts studied. The general population prevalences reported vary between 60.6% and 90.0%2; in Colombia, 40.2% of adults aged between 18 and 44 years and 41.4% of adults aged 45 years or older have suffered at least one traumatic event, and one-third of those who have been exposed to intrafamily violence report psychological trauma3.

In a World Health Organisation (WHO) study conducted in 21 countries, more than 10% of the respondents stated that they had witnessed acts of violence: 21.8% had suffered interpersonal violence,18.8% accidents, 17.7% exposure to armed conflict, and 16.2% traumatic events related to loved ones.4

The literature confirms the greater prevalence of mental disorders in populations exposed to traumatic events.5 Three general theories have been proposed for the relationship between mental disorders and life events: a) the quantitative theory (Holmes et al.,6 1967), which proposes a cumulative effect of the stress model, in which the quantity and the weight of life events, albeit not their quality or significance, are related to psychopathology; b) the qualitative theory (Paykel,7 1971), which proposes that it is not the change related to the trauma in itself but rather the undesirable nature of the change that generates the stress and the latter's adverse consequences, and c) the specific qualitative theory (Seligman,8 1967), which indicates that there are specific events that determine specific disorders.

Colombia is a country subjected to situations of violence, some of them part of the armed social conflict which for 60 years has pitted Colombians against each other, as guerrillas, drug traffickers, paramilitaries, armed forces or civil population, leaving thousands of peoples dead, missing and displaced.9 The violence in Colombia has been one of the main causes of death, hospitalisation, emergency room care and disability.10

Between 1998 and 2012, there were 331,470 homicides, with an average of 22,098 homicides per year.11 There are currently 8,307,777 registered victims of the armed conflict, and the country has 7.4 million internally displaced persons, which has only recently been surpassed by the war in Syria.12

The situations of trauma and violence offer an opportunity to examine how these events are related to mental disorders. In this context, in the last three decades, Itagüí-Antioquia has been identified as a municipality with high rates of homicide, criminality and intrafamily violence.13

The objective of this study is to compare the prevalence and the sociodemographic characteristics of some mental disorders from the standpoint of five groups of traumatic events and violence in the general population of Itagüí-Antioquia.

Material and methodsStudy designAn observational, descriptive prevalence study was conducted on the basis of secondary information from the Itagüí mental health study14, a population study that applied the methodology of the World Mental Health Survey, making it possible to estimate, as main outcome indicators, the frequency of the mental disorders studied using the lifetime prevalence ratios, in the last 12 months and in the last 30 days, according to the DSM-IV criteria. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in the home.

Characteristics of the municipality of ItagüíThe municipality of Itagüí, one of Colombia's smallest and most densely populated, covers a surface area of 21.09 km2. In 2012, according to the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [National Administrative Department of Statistics], the population was 258,520 inhabitants, 91% of them living in an urban area. With regard to distribution by age groups, 4% were under 5 years old; 24% were under 15 years; 9% were above 60 years; 9% were adolescents between 15 and 19 years, and 34% were women of childbearing age (between 10 and 49 years). 47.7% of the population are in the medium-low socio-economic bracket, followed by low (42.8%) and low-low (6.8%). The unemployment rate of men and women in the urban area was 10.9%, and 12.5% in the rural area. The general mortality rate for 2011 was 4.7/1,000 inhabitants The main causes of death in 2011 were ischaemic heart disease and respiratory diseases; assaults (homicides) were the main cause of death among the young population.

Study populationThe study comprised the general non-institutionalised population residing in the urban area, with fixed abode in the municipality of Itagüí in 2012 and aged between 13 and 65 years, chosen at random.

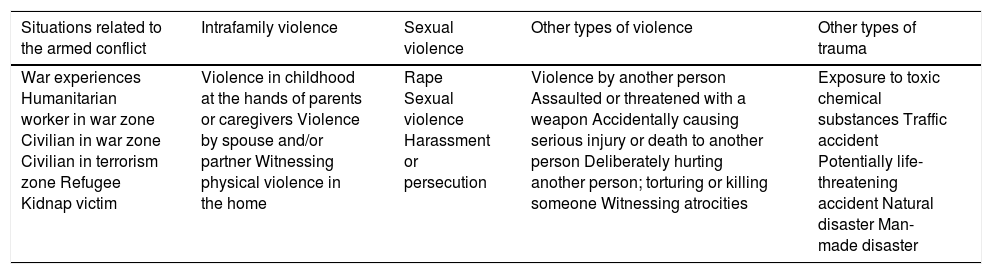

CriteriaThe inclusion criteria were: a) a background of a traumatic life event; b) aged from 13–65 years, and c) both sexes. The exclusion criterion was lack of information about the study variables. For the study purposes, a case is defined as a person who responded in the affirmative to any of the questions probing about 21 traumatic events included in the study and which the CIDI interview introduced as follows: "In the next part of the interview, we are going to talk about highly stressful events that may have occurred to you in the course of your life…" Table 1 shows how the different traumatic and violence-related events were grouped together.

Groups of traumatic events included in the study.

| Situations related to the armed conflict | Intrafamily violence | Sexual violence | Other types of violence | Other types of trauma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| War experiences Humanitarian worker in war zone Civilian in war zone Civilian in terrorism zone Refugee Kidnap victim | Violence in childhood at the hands of parents or caregivers Violence by spouse and/or partner Witnessing physical violence in the home | Rape Sexual violence Harassment or persecution | Violence by another person Assaulted or threatened with a weapon Accidentally causing serious injury or death to another person Deliberately hurting another person; torturing or killing someone Witnessing atrocities | Exposure to toxic chemical substances Traffic accident Potentially life-threatening accident Natural disaster Man-made disaster |

The sample size was calculated with the formula for the estimation of a population proportion, using a confidence interval of 99%, a precision of 5% and an estimated prevalence of 5.9%, the annual prevalence expected for depression according to the results of the Primer Estudio de Salud Mental, Medellín [First Mental Health Study, Medellín] 2011−2012. The sample size calculated was 900 persons, who were regarded as final units for the study analysis. The survey was finally applied to 896 persons from different socio-economic strata in the six communities of Itagüí. The interview was conducted in each selected house.

InstrumentThe WHO-CIDI interview, a highly structured psychiatric interview that makes it possible to diagnose psychiatric disorders according to the DSM-IV criteria, was used. For this study, the CIDI-CAPI version used in the Primer Estudio de Salud Mental, Medellín15 was used. The CIDI comprises two stages. The first one screens for any mental disorder. If it is positive, the interviewee goes on to the second stage. Twenty-five percent (25%) of the interviewees with a negative result in the first stage were selected randomly to complete the second stage to guarantee a suitable number of possible cases and controls. Personnel with no experience in mental health and trained by the team of investigators applied the interview. The questionnaire took approximately two hours, depending on the number of affirmative answers given by each interviewee.

VariablesThe study's dependent variable was a history of a traumatic life event. The traumatic events screened in the CIDI interview were grouped into five categories: a) situations related to the Colombian armed conflict; b) intrafamily violence c) sexual violence d) other types of violence, and e) trauma. Table 1 presents the traumatic situations that comprise each group. Other variables included in the study were: sociodemographic (age, gender, level of education, marital status) and clinical psychiatric (affective disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, childhood- and adolescent-onset disorders, and suicidal behaviour - suicidal ideation, plans and attempts).

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the sociodemographic and clinical variables was performed. The epidemiological indicators used were prevalences of mental disorders in the five groups of traumatic events in the study population. As each variable did not present a normal distribution, the median [interquartile range] is presented. The qualitative variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Statistically significant differences were sought in the prevalences of mental disorders in the five groups of traumatic disorders by means of the χ2 test, and a level of statistical significance of 5% (p < 0.05) was established.

BiasesThis study may have been affected by the following biases: a) screening, which was minimised by the sample design with the selection probability up to the household level; the design selected was probabilistic and multi-stage in a non-institutionalised general population, and b) information, minimised by using the CIDI structure interview, used in World Mental Health studies and with suitable validity, sensitivity and specificity for the mental disorders included. The version used in this study was already applied in the Medellín first mental health study and was linguistically and culturally validated.15 This manuscript was reviewed for publication following the STROBE guidelines for observational studies.16

Ethical considerationsThis investigation was approved by the University Research Committee. According to Resolution 8430 of Colombia, this research is classified as "risk-free". The primary study secured the informed consent of adults and the assent of minors and the informed consent of their parents or guardians. Confidentiality of the information analysed was guaranteed at all times. The information was analysed with the SPSS version 21.0 software (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, Illinois, United States), under a licence granted to the Universidad CES.

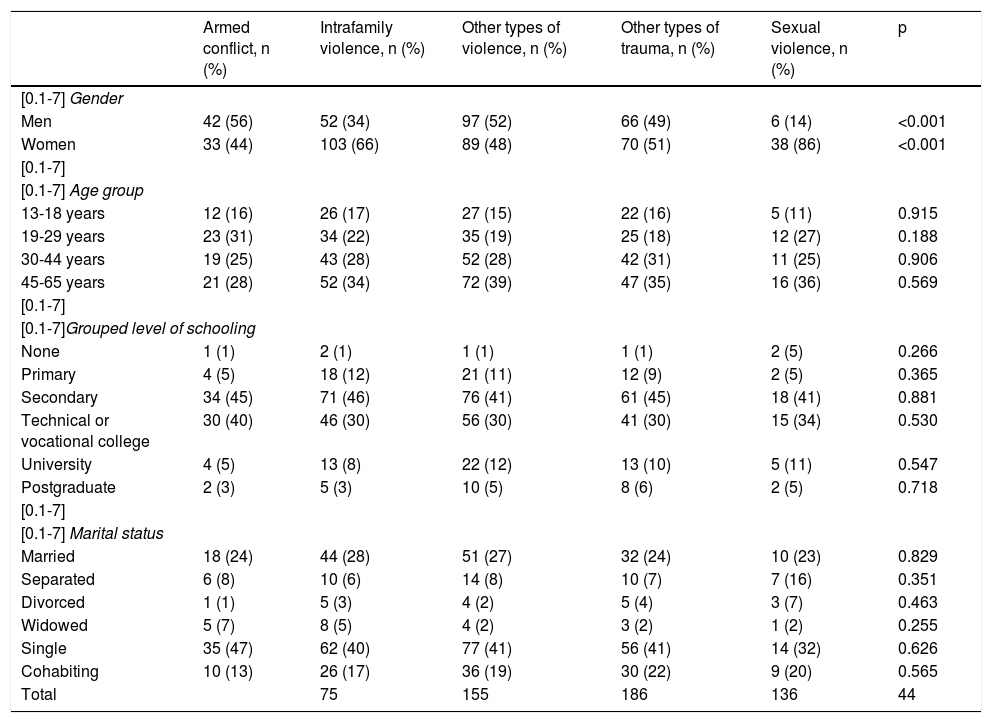

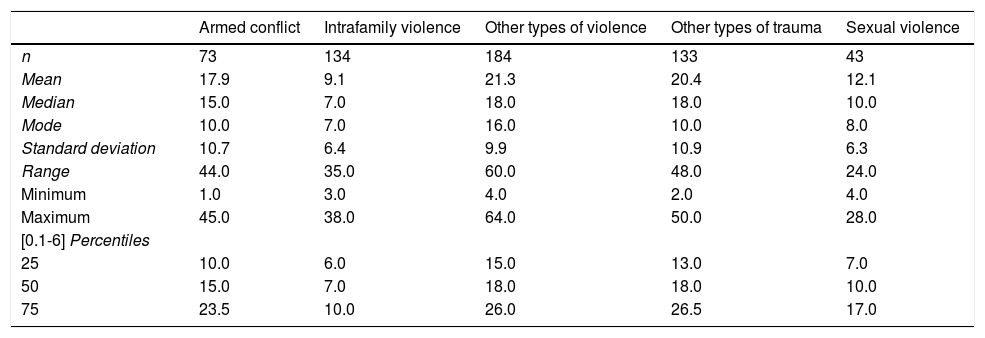

ResultsA total of 294 people were included, from whom complete information about all the study variables was obtained. The people were evaluated according to the traumatic event that they defined as the most important traumatic experience in their life. Age at the time of these traumatic events ranged from 7 to 18 years (Table 2). When the sociodemographic variables were compared in the different groups of traumatic events, differences by gender were found in the sexual and intrafamily violence groups, in which 86% and 66% were women. No significant differences were observed between the groups in the other sociodemographic variables (Table 3).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population by trauma and violence group.

| Armed conflict, n (%) | Intrafamily violence, n (%) | Other types of violence, n (%) | Other types of trauma, n (%) | Sexual violence, n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0.1-7] Gender | ||||||

| Men | 42 (56) | 52 (34) | 97 (52) | 66 (49) | 6 (14) | <0.001 |

| Women | 33 (44) | 103 (66) | 89 (48) | 70 (51) | 38 (86) | <0.001 |

| [0.1-7] | ||||||

| [0.1-7] Age group | ||||||

| 13-18 years | 12 (16) | 26 (17) | 27 (15) | 22 (16) | 5 (11) | 0.915 |

| 19-29 years | 23 (31) | 34 (22) | 35 (19) | 25 (18) | 12 (27) | 0.188 |

| 30-44 years | 19 (25) | 43 (28) | 52 (28) | 42 (31) | 11 (25) | 0.906 |

| 45-65 years | 21 (28) | 52 (34) | 72 (39) | 47 (35) | 16 (36) | 0.569 |

| [0.1-7] | ||||||

| [0.1-7]Grouped level of schooling | ||||||

| None | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (5) | 0.266 |

| Primary | 4 (5) | 18 (12) | 21 (11) | 12 (9) | 2 (5) | 0.365 |

| Secondary | 34 (45) | 71 (46) | 76 (41) | 61 (45) | 18 (41) | 0.881 |

| Technical or vocational college | 30 (40) | 46 (30) | 56 (30) | 41 (30) | 15 (34) | 0.530 |

| University | 4 (5) | 13 (8) | 22 (12) | 13 (10) | 5 (11) | 0.547 |

| Postgraduate | 2 (3) | 5 (3) | 10 (5) | 8 (6) | 2 (5) | 0.718 |

| [0.1-7] | ||||||

| [0.1-7] Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 18 (24) | 44 (28) | 51 (27) | 32 (24) | 10 (23) | 0.829 |

| Separated | 6 (8) | 10 (6) | 14 (8) | 10 (7) | 7 (16) | 0.351 |

| Divorced | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 4 (2) | 5 (4) | 3 (7) | 0.463 |

| Widowed | 5 (7) | 8 (5) | 4 (2) | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 0.255 |

| Single | 35 (47) | 62 (40) | 77 (41) | 56 (41) | 14 (32) | 0.626 |

| Cohabiting | 10 (13) | 26 (17) | 36 (19) | 30 (22) | 9 (20) | 0.565 |

| Total | 75 | 155 | 186 | 136 | 44 | |

Descriptive statistics of age at the time of the traumatic event, by trauma and violence groups.

| Armed conflict | Intrafamily violence | Other types of violence | Other types of trauma | Sexual violence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 73 | 134 | 184 | 133 | 43 |

| Mean | 17.9 | 9.1 | 21.3 | 20.4 | 12.1 |

| Median | 15.0 | 7.0 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 10.0 |

| Mode | 10.0 | 7.0 | 16.0 | 10.0 | 8.0 |

| Standard deviation | 10.7 | 6.4 | 9.9 | 10.9 | 6.3 |

| Range | 44.0 | 35.0 | 60.0 | 48.0 | 24.0 |

| Minimum | 1.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| Maximum | 45.0 | 38.0 | 64.0 | 50.0 | 28.0 |

| [0.1-6] Percentiles | |||||

| 25 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 15.0 | 13.0 | 7.0 |

| 50 | 15.0 | 7.0 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 10.0 |

| 75 | 23.5 | 10.0 | 26.0 | 26.5 | 17.0 |

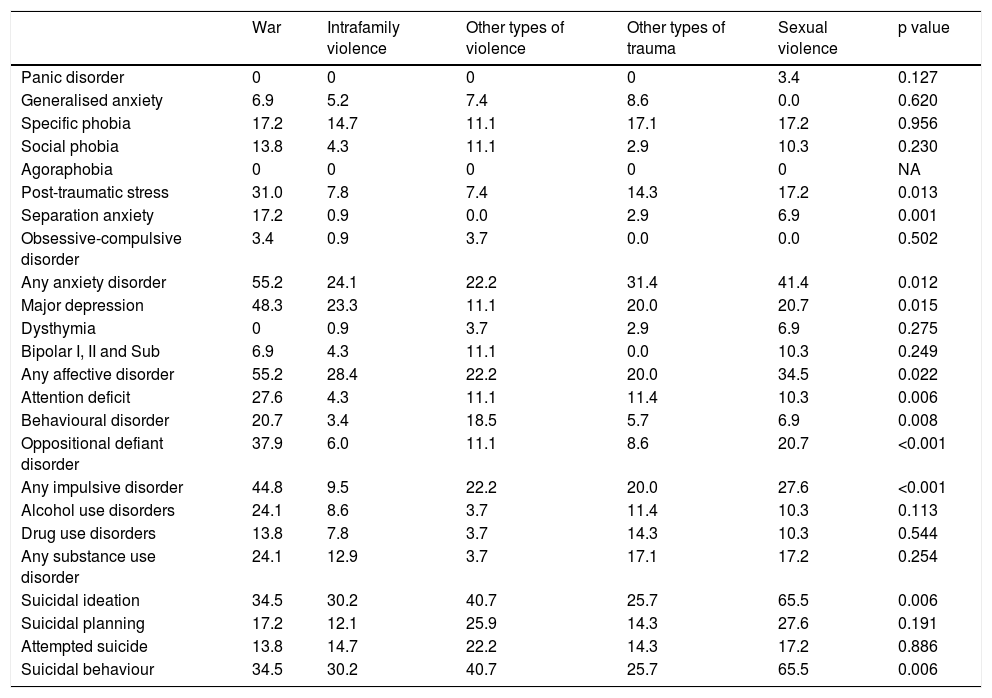

The prevalence of the mental disorders included was determined in each group of traumatic event. The population was segmented into two age groups, ≤13 years and ≥14 years (Table 4 and Table 5).

Prevalences (%) of mental disorders by traumatic event occurring at ≤13 years of age.

| War | Intrafamily violence | Other types of violence | Other types of trauma | Sexual violence | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panic disorder | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.4 | 0.127 |

| Generalised anxiety | 6.9 | 5.2 | 7.4 | 8.6 | 0.0 | 0.620 |

| Specific phobia | 17.2 | 14.7 | 11.1 | 17.1 | 17.2 | 0.956 |

| Social phobia | 13.8 | 4.3 | 11.1 | 2.9 | 10.3 | 0.230 |

| Agoraphobia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Post-traumatic stress | 31.0 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 14.3 | 17.2 | 0.013 |

| Separation anxiety | 17.2 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 0.001 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 3.4 | 0.9 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.502 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 55.2 | 24.1 | 22.2 | 31.4 | 41.4 | 0.012 |

| Major depression | 48.3 | 23.3 | 11.1 | 20.0 | 20.7 | 0.015 |

| Dysthymia | 0 | 0.9 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 0.275 |

| Bipolar I, II and Sub | 6.9 | 4.3 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 10.3 | 0.249 |

| Any affective disorder | 55.2 | 28.4 | 22.2 | 20.0 | 34.5 | 0.022 |

| Attention deficit | 27.6 | 4.3 | 11.1 | 11.4 | 10.3 | 0.006 |

| Behavioural disorder | 20.7 | 3.4 | 18.5 | 5.7 | 6.9 | 0.008 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 37.9 | 6.0 | 11.1 | 8.6 | 20.7 | <0.001 |

| Any impulsive disorder | 44.8 | 9.5 | 22.2 | 20.0 | 27.6 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use disorders | 24.1 | 8.6 | 3.7 | 11.4 | 10.3 | 0.113 |

| Drug use disorders | 13.8 | 7.8 | 3.7 | 14.3 | 10.3 | 0.544 |

| Any substance use disorder | 24.1 | 12.9 | 3.7 | 17.1 | 17.2 | 0.254 |

| Suicidal ideation | 34.5 | 30.2 | 40.7 | 25.7 | 65.5 | 0.006 |

| Suicidal planning | 17.2 | 12.1 | 25.9 | 14.3 | 27.6 | 0.191 |

| Attempted suicide | 13.8 | 14.7 | 22.2 | 14.3 | 17.2 | 0.886 |

| Suicidal behaviour | 34.5 | 30.2 | 40.7 | 25.7 | 65.5 | 0.006 |

NA: not applicable.

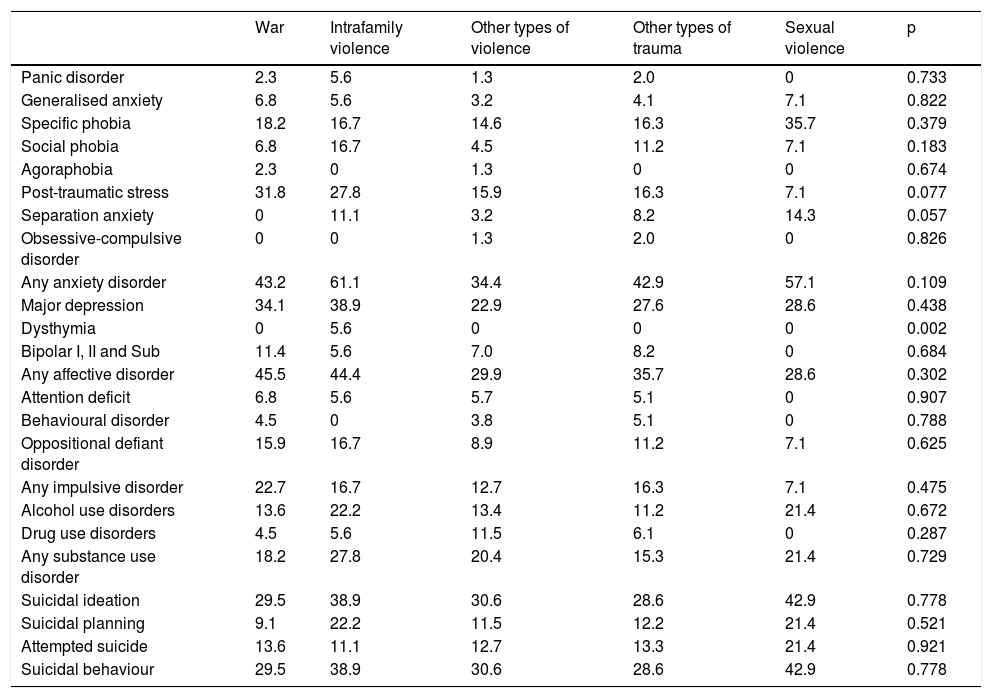

Prevalences (%) of mental disorders by traumatic event occurring at age ≤14 years.

| War | Intrafamily violence | Other types of violence | Other types of trauma | Sexual violence | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panic disorder | 2.3 | 5.6 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.733 |

| Generalised anxiety | 6.8 | 5.6 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 7.1 | 0.822 |

| Specific phobia | 18.2 | 16.7 | 14.6 | 16.3 | 35.7 | 0.379 |

| Social phobia | 6.8 | 16.7 | 4.5 | 11.2 | 7.1 | 0.183 |

| Agoraphobia | 2.3 | 0 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.674 |

| Post-traumatic stress | 31.8 | 27.8 | 15.9 | 16.3 | 7.1 | 0.077 |

| Separation anxiety | 0 | 11.1 | 3.2 | 8.2 | 14.3 | 0.057 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.826 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 43.2 | 61.1 | 34.4 | 42.9 | 57.1 | 0.109 |

| Major depression | 34.1 | 38.9 | 22.9 | 27.6 | 28.6 | 0.438 |

| Dysthymia | 0 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Bipolar I, II and Sub | 11.4 | 5.6 | 7.0 | 8.2 | 0 | 0.684 |

| Any affective disorder | 45.5 | 44.4 | 29.9 | 35.7 | 28.6 | 0.302 |

| Attention deficit | 6.8 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 0 | 0.907 |

| Behavioural disorder | 4.5 | 0 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 0 | 0.788 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 15.9 | 16.7 | 8.9 | 11.2 | 7.1 | 0.625 |

| Any impulsive disorder | 22.7 | 16.7 | 12.7 | 16.3 | 7.1 | 0.475 |

| Alcohol use disorders | 13.6 | 22.2 | 13.4 | 11.2 | 21.4 | 0.672 |

| Drug use disorders | 4.5 | 5.6 | 11.5 | 6.1 | 0 | 0.287 |

| Any substance use disorder | 18.2 | 27.8 | 20.4 | 15.3 | 21.4 | 0.729 |

| Suicidal ideation | 29.5 | 38.9 | 30.6 | 28.6 | 42.9 | 0.778 |

| Suicidal planning | 9.1 | 22.2 | 11.5 | 12.2 | 21.4 | 0.521 |

| Attempted suicide | 13.6 | 11.1 | 12.7 | 13.3 | 21.4 | 0.921 |

| Suicidal behaviour | 29.5 | 38.9 | 30.6 | 28.6 | 42.9 | 0.778 |

High prevalences of the different mental disorders were found in this group. When examined by grouped mental disorders, anxiety disorders present the greatest prevalence (55.2% of those with this type of trauma). By individual disorders, major depression reached a prevalence of 48.3%, followed by oppositional defiant disorder (37.9%) and suicidal ideation (34.5%).

Intrafamily violenceIn the grouped mental disorders, suicidal behaviour presented the highest prevalence (30.2%). Individually, suicidal ideation (30.2%) and major depression (23.3%) were the most prominent.

Other types of violenceBy groups of mental disorders, the prevalence of suicidal behaviour was most prominent (40.7%). Individually, it was behavioural disorder (18.5%).

Other types of traumaBy groups of behaviours, anxiety disorders were the most prominent, with 31.4%. Individually, they were suicidal ideation (25.7%), followed by major depression (20%), drug use disorder (14.3)% and post-traumatic stress disorder (14.3%).

Sexual violenceThis group presented the highest prevalence of suicidal behaviour, 65.5%. Among the individual disorders, major depression and oppositional defiant disorder were prominent, with a prevalence of 20.7%.

In the group of traumatic events related to the armed conflict, prevalences of 31% of traumatic stress disorder and 17.2% of separation anxiety disorder were observed, constituting a significant difference versus the other groups of traumatic events (p = 0.013 and p = 0.001). Major depression in the group related to the conflict presented a prevalence of 48.3%, significantly different with regard to the other groups (p = 0.015).

All the prevalences of childhood-onset disorders presented significant differences in the group of violence related to the armed conflict (p < 0.0001). No significant difference in substance use disorders was observed between the groups. The prevalences of drug use disorder were 14.3% in the group for other types of trauma and 13.8% in the group for violence related to the Colombian armed conflict. The prevalence of suicidal ideation (65.0%) was significantly greater in the sexual violence group (p = 0.006).

Mental disorders in the population with a traumatic event occurring at the age of 14 or overTraumaticevent related to the Colombian armed conflictThe grouped mental disorders with greatest prevalence in this group were affective disorders (45.5%). Individually, major depression (34.1%), post-traumatic stress (31.8%) and suicidal ideation (29.5%) were the most highly-prevalent.

Intrafamily violenceIn this traumatic group, the most prevalent grouped mental disorders were anxiety disorders (61.1%). Individually, they were major depression (38.9%), post-traumatic stress (27.8%) and alcohol use disorders (22.2%).

Other types of violenceThe grouped anxiety disorders were the most highly prevalent (34.4%). Individually, they were suicidal ideation (30.6%), major depression (22.9%) and post-traumatic stress (15.9%).

Other types of traumaThe grouped anxiety disorders presented the highest prevalence (42.9%). Separately, the most prevalent were suicidal ideation (28.6%), major depression (27.6%) and post-traumatic stress disorder (16.3%).

Sexual violenceThe grouped anxiety disorders presented the greatest prevalence (57.1%). Individually, the most prevalent were suicidal ideation (42.9%), specific phobia (35.7%), major depression (28.6%) and alcohol use disorders (21.4%).

In this age group, a significant difference was only found in the intrafamily violence group in dysthymia, with a prevalence of 5.6% (p = 0.002). Table 4 shows the major prevalences of each mental disorder according to trauma category and compares them by age groups (≤13 years and ≥14 years).

DiscussionThis population study with individuals aged between 13 and 65 years explored the occurrence of traumatic events and the presence of mental disorders. The results are representative of the general population. The main finding of this study is the high prevalence of mental disorders in people exposed to traumatic situations throughout their lives. These prevalences were greater in the group that suffered the trauma at ≤13 years of age, where significant differences were observed in certain categories of traumatic events, such as armed conflict-related violence and sexual violence. These findings coincide with studies that have identified exposure to trauma in childhood as a risk factor for mental disease.14,17

In a recent meta-analysis, Hughes et al.18 found that exposure to four life events is associated with an increase in the risk of poor mental, physical and sexual health, substance use, exposure to violence as a victim or perpetrator, and physical inactivity. Therefore, the effects of early traumatic experiences are far-reaching and diffused. This study allows us to observe early exposure to different forms of violence and trauma.

Post-traumatic stress and traumatic eventsIn a study with Syrian refugees, Cheung et al.19 found a prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder of 43.0%, versus 5.52% for anxiety and 5.69% for depression. These results differ from our own, since while depression and post-traumatic stress presented high prevalences, in our study depression was more prevalent (38.9% versus 27.8%).

In a study that included 301 adolescents, Wright et al.20 found that a history of negligence and emotional abuse in childhood were significantly associated with depression and anxiety symptoms. In our study, we found that among children with some type of traumatic event in the first 13 years of life, 24.1% of those who suffered intrafamily violence presented some type of anxiety disorder. In the 2015 Mental Health Survey, the risk of adults aged 45 years and over exposed to traumatic events in Colombia is 3.12% (95% confidence interval [95%CI], 2.36%-4.12%) and 3.29% in those aged 18 to 44 years (95%CI, 2.57%-4.21%).21

Major depression and traumatic eventsIn our study, the greater prevalences of depression were associated, in the group of traumas occurring up until the age of 13, with situations related to the Colombian armed conflict and, in over-14 s, with intrafamily violence. Until only recently, it was considered that young children did not remember or did not understand exposure to traumatic events.22 However, the effects of war, trauma and armed conflict in the young are becoming increasingly clearer.23

In a study by Vitriol et al., 50%-80% of adults presenting with depression identified at least one traumatic childhood event.24,25 Horesh et al.26 conducted a study of stressful events in life and depression, finding that events related to affective losses were significantly greater in the depression group (p < 0.05).

Suicidal behaviour and traumatic eventsSuicidal behaviour has been associated with exposure to traumatic events and violence. Some mechanisms proposed are the perturbation generated by trauma in interpersonal relationships and present and future confidence in social ties.27

In our study, the greatest prevalence of suicidal behaviour was observed in the sexual violence group, in which 4 out of 10 people had presented suicidal behaviour and 2 out of 5 attempted suicide, similar to the findings reported in a study28 in which exposure to multiple traumatic childhood events was associated with suicide attempts (odds ratio [OR] = 30.14; 95% CI, 14.73–61.67).

Disorders caused by substance use and trauma eventsStressful life experiences have been associated with alcohol consumption disorders.29 In our study, intrafamily violence was associated with greater prevalence of alcohol use disorder, followed by sexual violence. This association between trauma and substance use disorder has been reported mainly in women.30

In a general population study, Kim et al.31 included 22,147 people who had consumed alcohol in the previous 12 months. Those with a history of exposure to three or more stressful events had a greater association with alcohol dependence (OR = 3,15; 95% CI, 2.30–4.33). In our study, 1 in 4 people exposed to situations related to armed conflict at ≤13 years of age had an alcohol consumption disorder.

With regard to exposure to traumatic events and drug use, Carliner et al.32 evaluated 9,956 adolescents and found that exposure to a traumatic event before the age of 11 years was associated with a greater risk of consumption of marijuana (relative risk [RR] = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.33–1.69), cocaine (RR = 2.78; 95% CI, 1.95–3.97) and multiple drugs (RR = 1.74; 95% CI, 1.37–2.20). Our study found the highest prevalences of drug consumption disorder in persons exposed to other traumas and to the armed conflict before the age of 14 years.

The findings of this study must be interpreted in the light of the following limitations. Firstly, this study did not investigate all the potential types of trauma with which a person may have to contend, and although 21 types of traumatic events were included, not all the traumas associated with mental disorders were included. Secondly, the time of exposure to the traumatic events was not evaluated. However, due to the very nature of the traumatic events assessed, in some cases a single exposure is sufficient, as occurs in sexual violence. Thirdly, both the traumatic events and the mental disorders were based on the interviewee's statements or assertions, which may be influenced by memory biases. Although a private and relaxed atmosphere was permitted, with a guarantee of anonymity that was conducive to disclosing events and mental symptoms, the accuracy of memory cannot be guaranteed. In fourth place, some mental disorders associated with traumatic events were not considered — such as borderline personality in schizophrenia —, because the database used did not include these diagnoses. In fifth place, being a cross-sectional study, we cannot talk about causality between the traumatic events and mental disorders. In sixth place, the primary study's sample design had different objectives to that of the present study.

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable information related to traumatic life events and the occurrence of mental disorders.

Finally, the findings of this study are consistent with the scientific literature related to the topic, which also states that exposure to traumatic life events, particularly in childhood, are a key factor associated with negative mental health outcomes. Although greater awareness has been obtained about the impact of sexual violence and violence related to armed conflicts or war situations, it is important to consider other traumatic events, such as intrafamily and interpersonal violence, as factors that can affect the mental health of sufferers. More local studies exploring the consequences of early exposure to trauma and violence from the standpoint of mental health outcomes are required. Future research could seek to determine protective factors for individuals exposed to trauma and violence.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Orrego S, Hincapié GMSM, Restrepo D. Trastornos mentales desde la perspectiva del trauma y la violencia en un estudio poblacional. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:262–270.