The aim of the study is to compare the emotional effects of COVID-19 among three different groups, namely: health personnel, medical students, and a sample of the general population.

Methods375 participants were recruited for this study, of which 125 were medical students (preclinical studies, 59; clinical studies, 66), 125 were health personnel (COVID-19 frontline personnel, 59; personnel not related with COVID-19, 66), and 125 belonged to the general population. The PHQ-9, GAD-7, and CPDI scales were used to assess the emotional impact. A multinomial logistic regression was performed to measure differences between groups, considering potential confounding factors.

ResultsRegarding CPDI values, all other groups showed reduced values compared to COVID-19 frontline personnel. However, the general population, preclinical and clinical medical students showed increased PHQ-9 values compared to COVID-19 frontline personnel. Finally, confounding factors, gender and age correlated negatively with higher CPDI and PHQ-9 scores.

ConclusionsBeing frontline personnel is associated with increased COVID-19-related stress. Depression is associated, however, with other groups not directly involved with the treatment of COVID-19 patients. Female gender and younger age correlated with COVID-19-related depression and stress.

Los estudiantes de educación superior son una población vulnerable a los trastornos mentales, más aún durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Su salud mental se ha visto afectada por el confinamiento, las dificultades en el desarrollo de las actividades académicas y las exigencias de las nuevas modalidades pedagógicas. Se planteó entonces la pregunta: en las instituciones de educación superior, ¿cuáles acciones en torno a a) promoción y prevención, b) atención a síntomas mentales y c) adaptaciones pedagógicas pueden desarrollarse con el fin de mejorar la salud mental de sus estudiantes?

MétodosSíntesis crítica a partir de la revisión sistemática de la literatura. Se realizó la búsqueda de artículos científicos de alcance descriptivo, analítico, experimental o evaluativo, así como recursos web de organizaciones relacionadas con el tema. Se realizó una síntesis en función de los 3 focos de la pregunta mediante comparación constante, hasta realizar la agrupación de acciones por similitud en los actores que las ejecutarían y recibirían. Se anticipó una baja calidad de la evidencia, por lo que no se realizó evaluación estandarizada.

ResultadosSe exploraron 68 artículos y 99 recursos web. Después de la revisión del texto completo se incluyeron 12 artículos científicos y 11 recursos web. Como lineamentos generales, se encontró que la propuesta más frecuente es el diseño de un programa estructurado específico para el tema de salud mental en las instituciones educativas, que sea multidisciplinario, incluyente, dinámico y sensible a la cultura. Las acciones deben ser divulgadas periódicamente para que los estudiantes y demás miembros de la comunidad educativa las tengan claras, e idealmente se propone mantenerlas hasta el periodo pospandémico e incluir a los egresados. Para a) la promoción y prevención, se encontró la psicoeducación por vía electrónica, donde se expliquen estilos de vida saludable, reacciones emocionales en pandemia, estrategias de afrontamiento y signos de alarma. Se propone la participación de los pares como estrategia de apoyo y espacios de interacción social que no se enfoquen únicamente en aspectos académicos. Se reporta la necesidad de cribar síntomas mentales por medio de envío frecuente de formularios en línea o aplicaciones móviles, donde también se indague por la satisfacción de las necesidades básicas y tecnológicas. En cuanto a b) atención de síntomas mentales, una de las acciones que se encontró con mayor frecuencia es disponer de un centro de consultoría que sea capaz de realizar atención en salud mental por vía telefónica, por tecnologías e incluso presencial, con atención permanente las 24 h o equipos de respuesta rápida ante una situación de crisis, como la conducta suicida y la violencia doméstica. Para c) las adaptaciones pedagógicas, se señala como requisito indispensable la comunicación fluida para tener instrucciones claras sobre el desarrollo de las actividades académicas para disminuir la incertidumbre y, por ende, la ansiedad y favorecer la gestión del tiempo por el estudiante. Los profesores y pedagogos de la institución pueden ofrecer asesorías directas (por videollamadas o reuniones de grupos en línea) para proveer apoyo en hábitos de estudios, materias propias de cada carrera y salud mental.

ConclusionesLos recursos incluidos proponen que la institución educativa cree un programa que aborde específicamente la salud mental de los estudiantes. Esta síntesis puede proveer lineamientos que faciliten la toma de decisiones, sin perder de vista que la institución y el estudiante están inmersos en un contexto complejo, con circunstancias y otros actores en varios niveles que también intervienen en la salud mental. Se requieren investigaciones sobre la evolución de la situación de salud mental y el efecto de las acciones que se vayan tomando.

The World Health Organisation declared the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection a pandemic in March 2020, after the first cases were reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019.1 The countries of the world have made multiple efforts to deal with the situation, including lockdown, isolation of cases and contacts, cancellation of mass events and the closure of educational institutions.2 As this has been a sudden situation with the potential to put our physical integrity in danger and requiring changes in way of life, it has affected the population as a stressful event. A psychological impact is therefore only to be expected and may be expressed through symptoms of mental ill-health. Anxiety, sadness, irritability, an increase in drug use, avoidance behaviours aimed at reducing transmission, aggressiveness that leads to domestic violence and even suicidal behaviours have all been described.3–8

There are vulnerability factors that make some individuals experience greater stress. Higher education students are a group which, even before the pandemic, were at high risk of suffering mental health disorders. It has been estimated that up to 20% of university students have a mental disorder, mainly involving anxiety, altered mood and substance use.9 As young adults, they may have genetic factors that interact with environmental factors at the university, such as academic load and demands, financial support, social interaction with peers and lecturers, and even traumatic experiences such as bullying.10,11 These mental health problems appear to persist and also affect post-graduate students, including those studying for PhDs.12 For this reason, although there are still barriers due to stigma, the numbers seeking mental health services at universities have increased.13,14

With this logic, the mental health of higher education students should be a priority amid the present pandemic. In addition to the effects described in the general population,15 there is evidence among students of anxiety symptoms related to difficulties in continuing with academic activities and uncertainty about their future career paths.16 It even seems that students' stress and anxiety levels were higher than in the university workers and lecturers.17 The demands of the new teaching modalities and the detrimental effect this stressful experience is having on performance have contributed to making university students a population vulnerable to mental disorders in this unprecedented world event.18

We therefore decided to carry out a literature review with the aim of providing guidance to decision-makers of higher education institutions on actions that may benefit the mental health of their students. The question we sought to answer was, “What actions can higher education institutions implement to improve the mental health of their students in the areas of a) promotion and prevention; b) care and treatment of symptoms of mental ill-health; and c) teaching adaptations?”.

Material and methodsCritical synthesis from the systematic review of the literature.

Eligibility criteriaDue to the novelty of the subject at the time of the search, we anticipated the need to consider a variety of resources as it was unlikely that any clinical trials or systematic reviews would have already been published. Inclusion criteria were any descriptive, analytical, experimental or evaluative report that presented a specific action (a clear task directed at a target audience), which was potentially implementable (in detail so it could be put into operation) by a member of a university community, with the aim of promoting mental health, preventing symptoms of mental ill-health, treating symptoms of mental ill-health or adapting teaching and curricular strategies to improve the mental health of its students, including health science students.

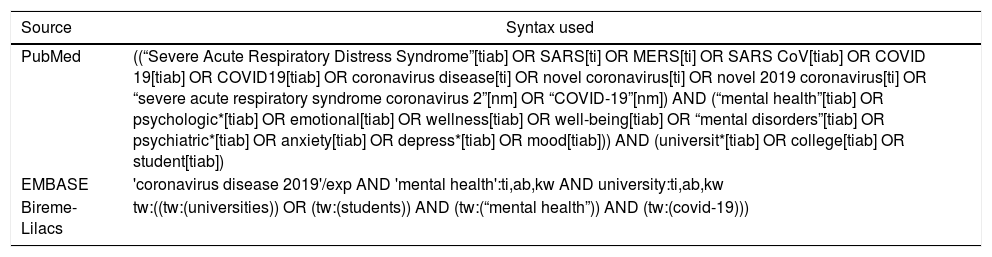

SearchThe search was completed on 3 August 2020 in the PubMed, EMBASE and Bireme databases. The websites of specialised libraries and portals of organisations related to the question were consulted to select articles, reports or any other publication of the grey literature with the potential to contain interventions. References that alluded to past epidemics were also included as they were considered a valuable source of experience. There were no restrictions in terms of language or publication date. It was designed by a document retrieval specialist from the Cochrane network and the full structure is shown in Table 1.

Database search strategy.

| Source | Syntax used |

|---|---|

| PubMed | ((“Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome”[tiab] OR SARS[ti] OR MERS[ti] OR SARS CoV[tiab] OR COVID 19[tiab] OR COVID19[tiab] OR coronavirus disease[ti] OR novel coronavirus[ti] OR novel 2019 coronavirus[ti] OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2”[nm] OR “COVID-19”[nm]) AND (“mental health”[tiab] OR psychologic*[tiab] OR emotional[tiab] OR wellness[tiab] OR well-being[tiab] OR “mental disorders”[tiab] OR psychiatric*[tiab] OR anxiety[tiab] OR depress*[tiab] OR mood[tiab])) AND (universit*[tiab] OR college[tiab] OR student[tiab]) |

| EMBASE | 'coronavirus disease 2019'/exp AND 'mental health':ti,ab,kw AND university:ti,ab,kw |

| Bireme-Lilacs | tw:((tw:(universities)) OR (tw:(students)) AND (tw:(“mental health”)) AND (tw:(covid-19))) |

Two investigators independently assessed article titles and abstracts and then the full text to decide on inclusion. For the web resources, each investigator scanned the web address found to check it met the criteria. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus. Agreement on the selection was quantified with the κ statistic.

Data extractionThe reports included were read and synthesised by the investigators using a pre-established format in Microsoft Excel to detail the specific action identified, its components and the theoretical or empirical basis it may have come from. In view of the expected variety of resources that would be included, the above format was pilot tested by two investigators with training in epidemiology and technology evaluation to determine its usability in the extraction of information.

SynthesisThrough constant comparison, each literature resource was analysed to identify one or various actions and the basis for implementation, in order that the actions could be grouped by similarity in terms of the actors implementing and those on the receiving end, and they were then summarised according to the three focuses in question. With the designs chosen, we anticipated low quality of evidence, so evaluation was not standardised.

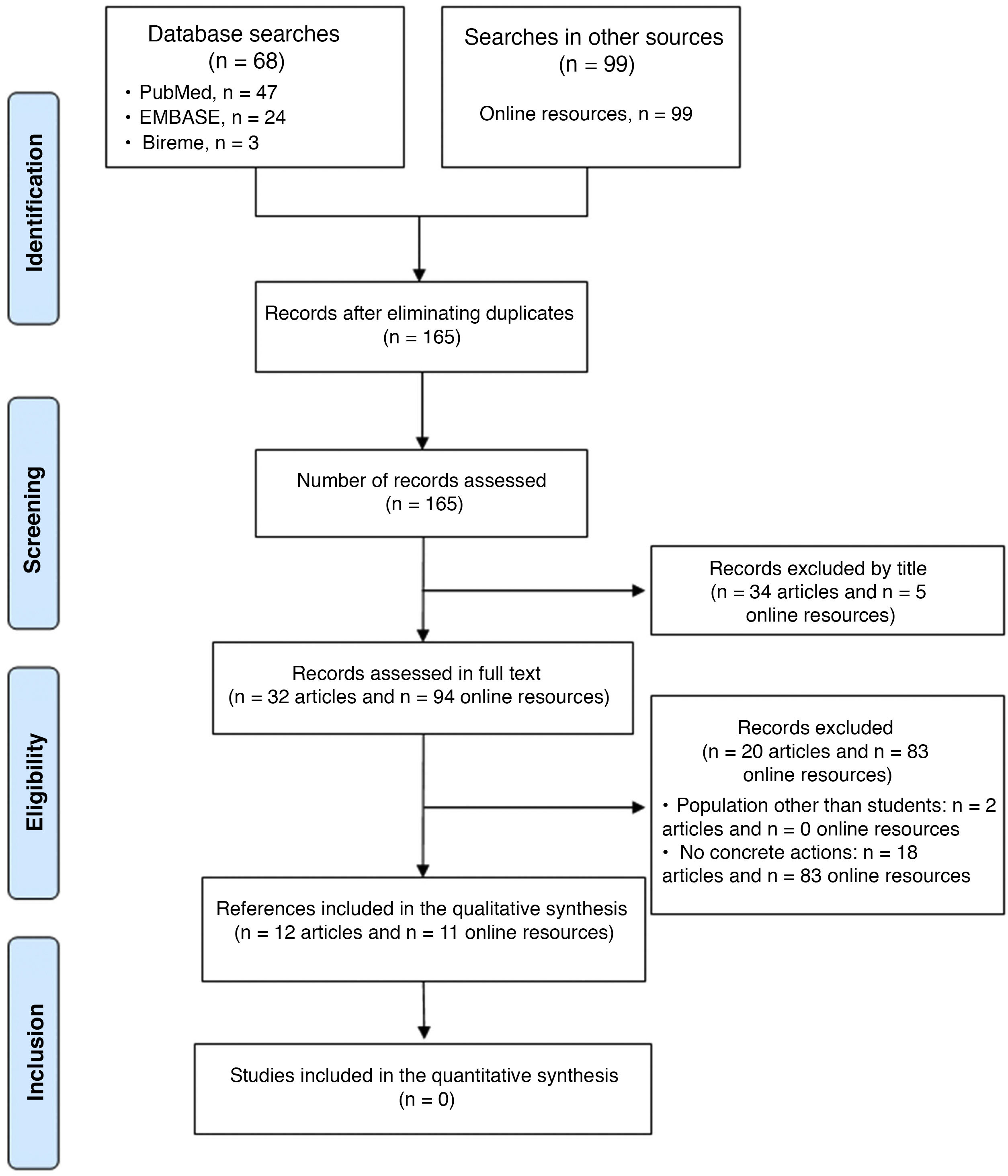

ResultsSearch and selectionA total of 68 articles and 99 online resources were examined and in the end, 12 scientific articles and 11 online resources were included (Fig. 1). The agreement on the selection was adequate (κ = 0.8; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.6–1.0).

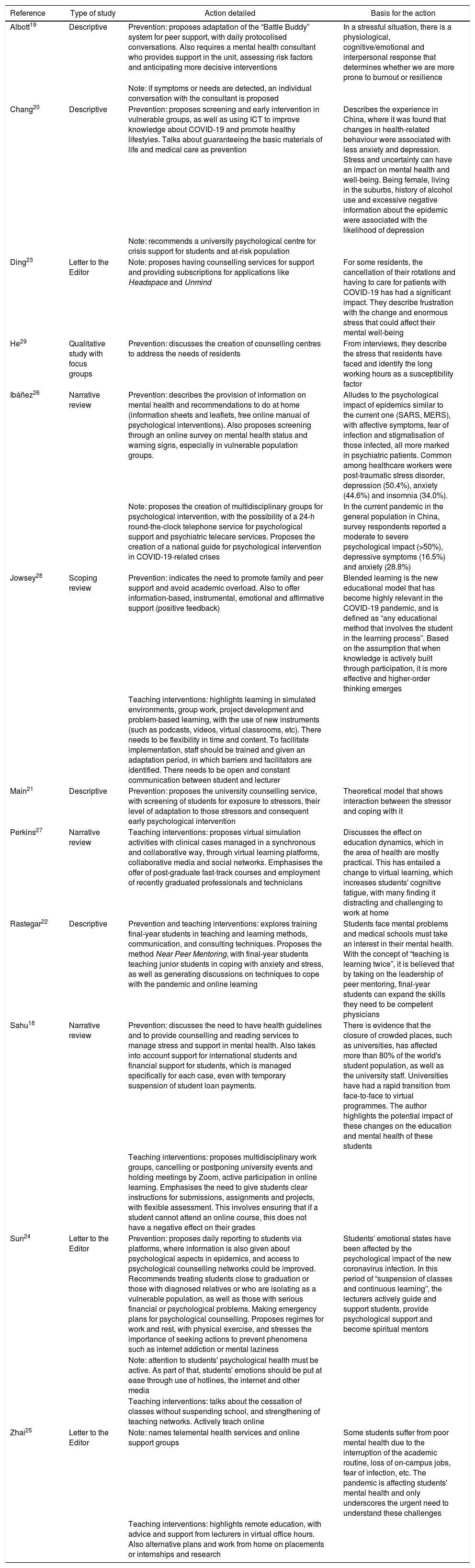

Characteristics of the studiesThe scientific articles found were mainly descriptive studies,19–22 but there were also letters to the editor,23–25 narrative reviews,18,26,27 a scoping review28 and a qualitative study with a focus group29 (Table 2). For online resources, we included press releases from healthcare organisations30 and education,31–33 as well as websites with specific resources for universities and students,34–39 plus mobile phone applications32 (Table 3). As anticipated, the quality of the evidence would be classified as low as these were descriptive studies and expert recommendations, so we did not carry out a formal evaluation. The specific actions identified are summarised below.

Scientific articles that propose actions for the mental health of university students.

| Reference | Type of study | Action detailed | Basis for the action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albott19 | Descriptive | Prevention: proposes adaptation of the “Battle Buddy” system for peer support, with daily protocolised conversations. Also requires a mental health consultant who provides support in the unit, assessing risk factors and anticipating more decisive interventions | In a stressful situation, there is a physiological, cognitive/emotional and interpersonal response that determines whether we are more prone to burnout or resilience |

| Note: if symptoms or needs are detected, an individual conversation with the consultant is proposed | |||

| Chang20 | Descriptive | Prevention: proposes screening and early intervention in vulnerable groups, as well as using ICT to improve knowledge about COVID-19 and promote healthy lifestyles. Talks about guaranteeing the basic materials of life and medical care as prevention | Describes the experience in China, where it was found that changes in health-related behaviour were associated with less anxiety and depression. Stress and uncertainty can have an impact on mental health and well-being. Being female, living in the suburbs, history of alcohol use and excessive negative information about the epidemic were associated with the likelihood of depression |

| Note: recommends a university psychological centre for crisis support for students and at-risk population | |||

| Ding23 | Letter to the Editor | Note: proposes having counselling services for support and providing subscriptions for applications like Headspace and Unmind | For some residents, the cancellation of their rotations and having to care for patients with COVID-19 has had a significant impact. They describe frustration with the change and enormous stress that could affect their mental well-being |

| He29 | Qualitative study with focus groups | Prevention: discusses the creation of counselling centres to address the needs of residents | From interviews, they describe the stress that residents have faced and identify the long working hours as a susceptibility factor |

| Ibáñez26 | Narrative review | Prevention: describes the provision of information on mental health and recommendations to do at home (information sheets and leaflets, free online manual of psychological interventions). Also proposes screening through an online survey on mental health status and warning signs, especially in vulnerable population groups. | Alludes to the psychological impact of epidemics similar to the current one (SARS, MERS), with affective symptoms, fear of infection and stigmatisation of those infected, all more marked in psychiatric patients. Common among healthcare workers were post-traumatic stress disorder, depression (50.4%), anxiety (44.6%) and insomnia (34.0%). |

| Note: proposes the creation of multidisciplinary groups for psychological intervention, with the possibility of a 24-h round-the-clock telephone service for psychological support and psychiatric telecare services. Proposes the creation of a national guide for psychological intervention in COVID-19-related crises | In the current pandemic in the general population in China, survey respondents reported a moderate to severe psychological impact (>50%), depressive symptoms (16.5%) and anxiety (28.8%) | ||

| Jowsey28 | Scoping review | Prevention: indicates the need to promote family and peer support and avoid academic overload. Also to offer information-based, instrumental, emotional and affirmative support (positive feedback) | Blended learning is the new educational model that has become highly relevant in the COVID-19 pandemic, and is defined as “any educational method that involves the student in the learning process”. Based on the assumption that when knowledge is actively built through participation, it is more effective and higher-order thinking emerges |

| Teaching interventions: highlights learning in simulated environments, group work, project development and problem-based learning, with the use of new instruments (such as podcasts, videos, virtual classrooms, etc). There needs to be flexibility in time and content. To facilitate implementation, staff should be trained and given an adaptation period, in which barriers and facilitators are identified. There needs to be open and constant communication between student and lecturer | |||

| Main21 | Descriptive | Prevention: proposes the university counselling service, with screening of students for exposure to stressors, their level of adaptation to those stressors and consequent early psychological intervention | Theoretical model that shows interaction between the stressor and coping with it |

| Perkins27 | Narrative review | Teaching interventions: proposes virtual simulation activities with clinical cases managed in a synchronous and collaborative way, through virtual learning platforms, collaborative media and social networks. Emphasises the offer of post-graduate fast-track courses and employment of recently graduated professionals and technicians | Discusses the effect on education dynamics, which in the area of health are mostly practical. This has entailed a change to virtual learning, which increases students' cognitive fatigue, with many finding it distracting and challenging to work at home |

| Rastegar22 | Descriptive | Prevention and teaching interventions: explores training final-year students in teaching and learning methods, communication, and consulting techniques. Proposes the method Near Peer Mentoring, with final-year students teaching junior students in coping with anxiety and stress, as well as generating discussions on techniques to cope with the pandemic and online learning | Students face mental problems and medical schools must take an interest in their mental health. With the concept of “teaching is learning twice”, it is believed that by taking on the leadership of peer mentoring, final-year students can expand the skills they need to be competent physicians |

| Sahu18 | Narrative review | Prevention: discusses the need to have health guidelines and to provide counselling and reading services to manage stress and support in mental health. Also takes into account support for international students and financial support for students, which is managed specifically for each case, even with temporary suspension of student loan payments. | There is evidence that the closure of crowded places, such as universities, has affected more than 80% of the world's student population, as well as the university staff. Universities have had a rapid transition from face-to-face to virtual programmes. The author highlights the potential impact of these changes on the education and mental health of these students |

| Teaching interventions: proposes multidisciplinary work groups, cancelling or postponing university events and holding meetings by Zoom, active participation in online learning. Emphasises the need to give students clear instructions for submissions, assignments and projects, with flexible assessment. This involves ensuring that if a student cannot attend an online course, this does not have a negative effect on their grades | |||

| Sun24 | Letter to the Editor | Prevention: proposes daily reporting to students via platforms, where information is also given about psychological aspects in epidemics, and access to psychological counselling networks could be improved. Recommends treating students close to graduation or those with diagnosed relatives or who are isolating as a vulnerable population, as well as those with serious financial or psychological problems. Making emergency plans for psychological counselling. Proposes regimes for work and rest, with physical exercise, and stresses the importance of seeking actions to prevent phenomena such as internet addiction or mental laziness | Students' emotional states have been affected by the psychological impact of the new coronavirus infection. In this period of “suspension of classes and continuous learning”, the lecturers actively guide and support students, provide psychological support and become spiritual mentors |

| Note: attention to students' psychological health must be active. As part of that, students' emotions should be put at ease through use of hotlines, the internet and other media | |||

| Teaching interventions: talks about the cessation of classes without suspending school, and strengthening of teaching networks. Actively teach online | |||

| Zhai25 | Letter to the Editor | Note: names telemental health services and online support groups | Some students suffer from poor mental health due to the interruption of the academic routine, loss of on-campus jobs, fear of infection, etc. The pandemic is affecting students' mental health and only underscores the urgent need to understand these challenges |

| Teaching interventions: highlights remote education, with advice and support from lecturers in virtual office hours. Also alternative plans and work from home on placements or internships and research |

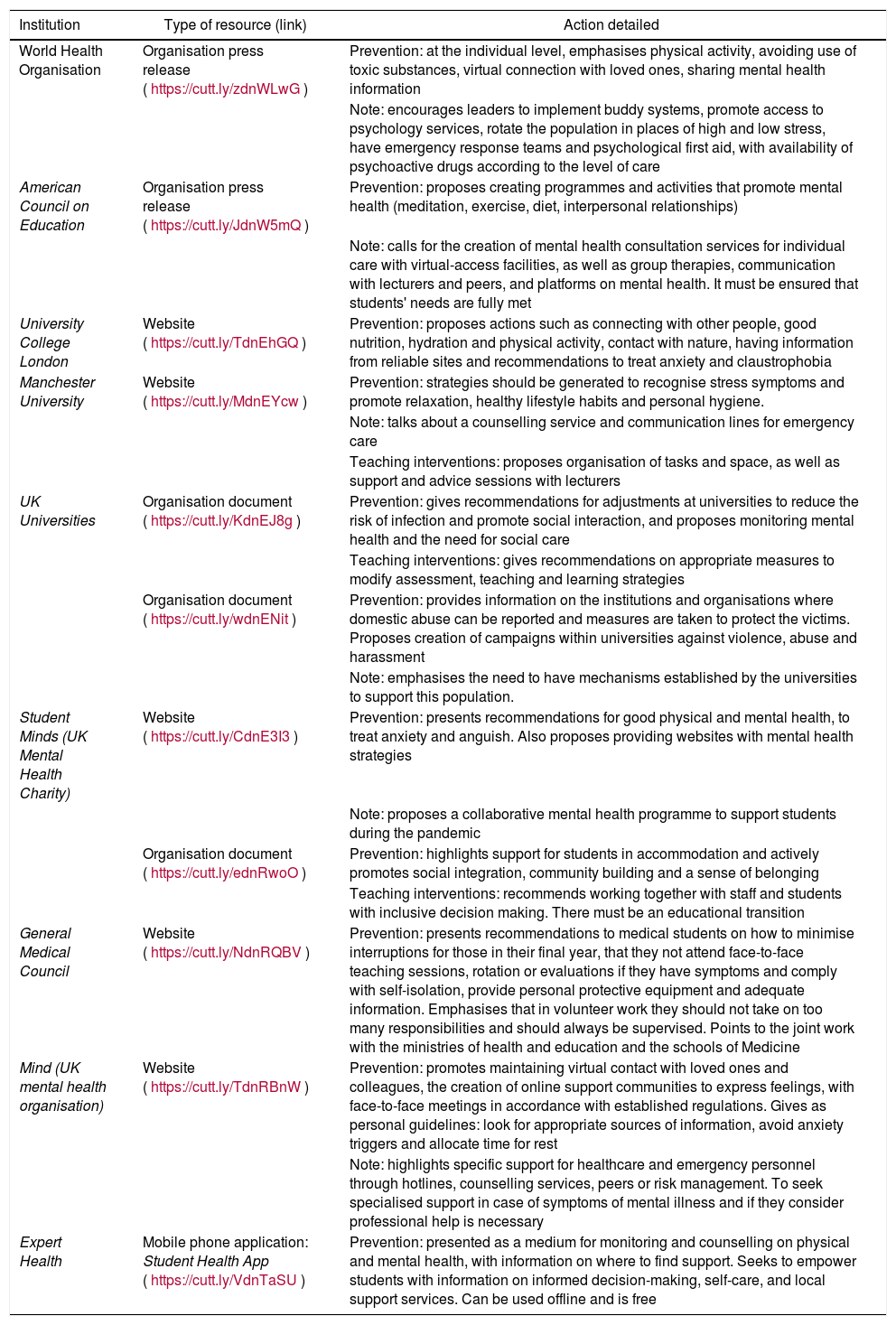

Online resources that propose actions for the mental health of university students.

| Institution | Type of resource (link) | Action detailed |

|---|---|---|

| World Health Organisation | Organisation press release (https://cutt.ly/zdnWLwG) | Prevention: at the individual level, emphasises physical activity, avoiding use of toxic substances, virtual connection with loved ones, sharing mental health information |

| Note: encourages leaders to implement buddy systems, promote access to psychology services, rotate the population in places of high and low stress, have emergency response teams and psychological first aid, with availability of psychoactive drugs according to the level of care | ||

| American Council on Education | Organisation press release (https://cutt.ly/JdnW5mQ) | Prevention: proposes creating programmes and activities that promote mental health (meditation, exercise, diet, interpersonal relationships) |

| Note: calls for the creation of mental health consultation services for individual care with virtual-access facilities, as well as group therapies, communication with lecturers and peers, and platforms on mental health. It must be ensured that students' needs are fully met | ||

| University College London | Website (https://cutt.ly/TdnEhGQ) | Prevention: proposes actions such as connecting with other people, good nutrition, hydration and physical activity, contact with nature, having information from reliable sites and recommendations to treat anxiety and claustrophobia |

| Manchester University | Website (https://cutt.ly/MdnEYcw) | Prevention: strategies should be generated to recognise stress symptoms and promote relaxation, healthy lifestyle habits and personal hygiene. |

| Note: talks about a counselling service and communication lines for emergency care | ||

| Teaching interventions: proposes organisation of tasks and space, as well as support and advice sessions with lecturers | ||

| UK Universities | Organisation document (https://cutt.ly/KdnEJ8g) | Prevention: gives recommendations for adjustments at universities to reduce the risk of infection and promote social interaction, and proposes monitoring mental health and the need for social care |

| Teaching interventions: gives recommendations on appropriate measures to modify assessment, teaching and learning strategies | ||

| Organisation document (https://cutt.ly/wdnENit) | Prevention: provides information on the institutions and organisations where domestic abuse can be reported and measures are taken to protect the victims. Proposes creation of campaigns within universities against violence, abuse and harassment | |

| Note: emphasises the need to have mechanisms established by the universities to support this population. | ||

| Student Minds (UK Mental Health Charity) | Website (https://cutt.ly/CdnE3I3) | Prevention: presents recommendations for good physical and mental health, to treat anxiety and anguish. Also proposes providing websites with mental health strategies |

| Note: proposes a collaborative mental health programme to support students during the pandemic | ||

| Organisation document (https://cutt.ly/ednRwoO) | Prevention: highlights support for students in accommodation and actively promotes social integration, community building and a sense of belonging | |

| Teaching interventions: recommends working together with staff and students with inclusive decision making. There must be an educational transition | ||

| General Medical Council | Website (https://cutt.ly/NdnRQBV) | Prevention: presents recommendations to medical students on how to minimise interruptions for those in their final year, that they not attend face-to-face teaching sessions, rotation or evaluations if they have symptoms and comply with self-isolation, provide personal protective equipment and adequate information. Emphasises that in volunteer work they should not take on too many responsibilities and should always be supervised. Points to the joint work with the ministries of health and education and the schools of Medicine |

| Mind (UK mental health organisation) | Website (https://cutt.ly/TdnRBnW) | Prevention: promotes maintaining virtual contact with loved ones and colleagues, the creation of online support communities to express feelings, with face-to-face meetings in accordance with established regulations. Gives as personal guidelines: look for appropriate sources of information, avoid anxiety triggers and allocate time for rest |

| Note: highlights specific support for healthcare and emergency personnel through hotlines, counselling services, peers or risk management. To seek specialised support in case of symptoms of mental illness and if they consider professional help is necessary | ||

| Expert Health | Mobile phone application: Student Health App (https://cutt.ly/VdnTaSU) | Prevention: presented as a medium for monitoring and counselling on physical and mental health, with information on where to find support. Seeks to empower students with information on informed decision-making, self-care, and local support services. Can be used offline and is free |

The most common proposal is the design of a specific programme for mental health at universities.18,20,21,25,26,29,31,37,39 All other actions are integrated into this programme, so the suggestion is that it should be designed by a multidisciplinary group of mental health professionals, educators and administrative personnel. It must be inclusive, in the sense that it always incorporates the vision of the students themselves,37 dynamic, so that it adapts and updates as emerging needs and barriers are identified, and culture-sensitive, as coping strategies can be different21; hence each institution should design its own programme to suit its own distinctive characteristics.

All actions should be reported on and disclosed periodically so that the entire educational community is clear about them. This is particularly important in the case of crises and emergency plans so they can be implemented immediately. This requires a platform for direct and fluid communication between the different members of the university and the students. Direct and continuous contact between students, lecturers, managers and other members of the university is recommended.

The university can also serve as a centre for reliable and relevant information to circulate news about the pandemic and the local situation. There seems to be an association between preventing false information and increasing knowledge about COVID-19 and a reduction in anxiety levels felt by students.20

Although the focus of the review is the students, it is important to stress that, in view of their direct interaction, strategies should also be designed to look after the mental health of lecturers, administrators and other members of the educational community.32,37 It would also be beneficial to encourage coordination between the university and other social actors, such as insurers and health service providers, government bodies, the legal system, financial operators and specific mental health organisations, to help deal more effectively with the needs identified.20

We found a proposal to choose indicators of the effect of the interventions which can be measured.21 Although they are not explicitly specified, we can deduce indicators such as the presence of symptoms and mental disorders, perceived well-being, the number and type of crises suffered and cared for, frequency with which students do not attend courses, measures of academic success and achievement of goals, and number of students seen. These indicators can be the input for research projects addressing issues related to interventions and their effectiveness; a necessity from a scientific point of view. The documents reviewed indicate the need to maintain mental healthcare programmes post-pandemic, when we may find a higher rate of psychological disorders29 and increased demand for mental health services.37

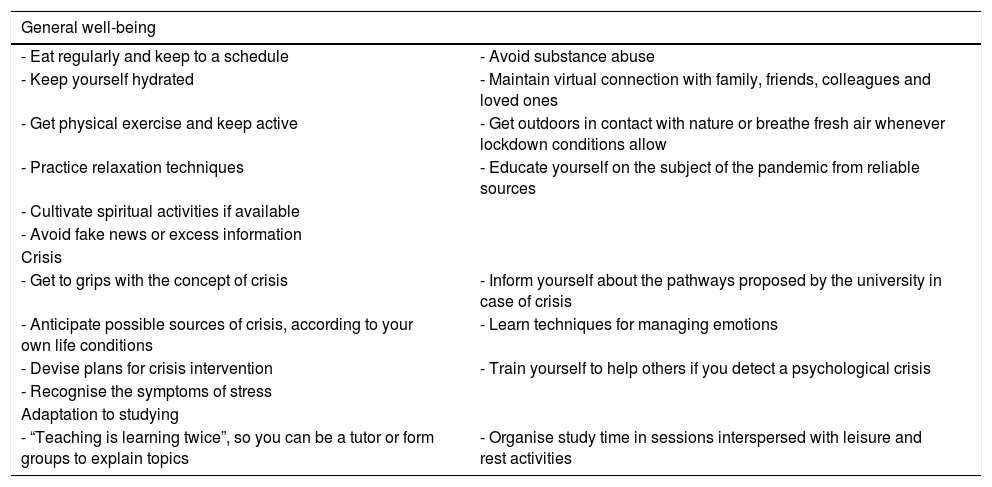

Promotion and prevention in mental healthPsychoeducationA number of the recommended actions in the sources reviewed involve the systematic delivery of information on mental health that can be grouped under the heading of psychoeducation. They include the promotion of individual actions for good mental health that can be broken down into recommendations for general well-being, coping with stressors and crises, and those related to studying (Table 4). Leaflets and manuals can be designed to be delivered electronically, giving tips for healthy lifestyles, explaining common emotional reactions to epidemics, advising on how to cope with isolation and periods of quarantine, and describing warning signs that require personalised assessment or even emergency care.26 These information resources should be available as material to be consulted at any time.36

Self-care recommendations for university students to promote mental health and prevent mental disorders.

| General well-being | |

|---|---|

| - Eat regularly and keep to a schedule | - Avoid substance abuse |

| - Keep yourself hydrated | - Maintain virtual connection with family, friends, colleagues and loved ones |

| - Get physical exercise and keep active | - Get outdoors in contact with nature or breathe fresh air whenever lockdown conditions allow |

| - Practice relaxation techniques | - Educate yourself on the subject of the pandemic from reliable sources |

| - Cultivate spiritual activities if available | |

| - Avoid fake news or excess information | |

| Crisis | |

| - Get to grips with the concept of crisis | - Inform yourself about the pathways proposed by the university in case of crisis |

| - Anticipate possible sources of crisis, according to your own life conditions | - Learn techniques for managing emotions |

| - Devise plans for crisis intervention | - Train yourself to help others if you detect a psychological crisis |

| - Recognise the symptoms of stress | |

| Adaptation to studying | |

| - “Teaching is learning twice”, so you can be a tutor or form groups to explain topics | - Organise study time in sessions interspersed with leisure and rest activities |

Compiled from the online resources included in the review.

Peer participation is also proposed as a support strategy. Among the experiences found was the “Battle Buddies” programme,19 which consists of assigning a “buddy” to each health sciences student (can be extended to other areas). This intervention is derived from the system used by the United States Army and the “anticipate, plan and deter” (APD) model used in disaster response. Individuals are paired according to their area, experience and seniority with the aim of having regular conversations on a daily basis, if necessary with the aid of prompts in the form of pre-established questions that specifically address work or academic and mental health aspects. It also includes the involvement of an expert consultant (who may be a member of the institution's mental health area) to support buddies in a particular area, facilitate group sessions to anticipate all the stressors that may arise, and plan the actions to address them, and this consultant is available to provide individual support in more serious situations as part of the deter phase of the model.

Another recommendation was found to promote social interaction, which includes topics beyond the academic.18,27 It could be wrong to assume that students will create their social groups through virtual means, as some may find it difficult or may not have the same access or skills to ask to join them. The idea is that the university facilitates spaces for interaction that also include leisure and mental health issues. In this regard, interactive spaces can be generated where students share the strategies they have used to cope with the pandemic, such as the forum “What worked for me”.37 Alternatively, support groups can be created by bringing together students who share interests or have other similarities to facilitate periodic virtual encounters, which can act as group therapy.25,31

Screening and population at riskThere are proposals to screen for symptoms of mental disorders, although no information was found on the specific instruments to achieve this. In view of the incidence, screening should cover symptoms of depression and anxiety, suicidal ideation and behaviour, insomnia, which could be an early marker of mental disorder,26 assessment of stress-producing events (in the family environment and financial), and the student's coping strategies.21 One possibility for implementing screening is by way of frequent submission of forms online18 or through lecturers and tutors in their day-to-day academic interaction. It has even been proposed that a member of the institution contact each student individually and directly to ensure that all their basic and technological needs are met.31

Mobile applications, which offer the advantage of facilitating frequent screening and monitoring of symptoms, as well as giving tips on mental health, can be used. Subscription to some applications like Headspace and Unmind have been sponsored by education centres so that, for example, students can do meditation and mindfulness exercises.23 Other free apps in English, such as Student Health, act as an archive for information and knowledge about COVID-19, and have frequent reminders with tips for promoting mental health and crisis care pathways.40

It is important to inquire about the degree of satisfaction with basic needs, including those related to technology and internet connection, due to the possibility of “digital poverty”.32 From that point of view, coordination with the financial system and local or national government bodies is essential to manage aid, loans and any financial assistance that students may require.18

The need for special assistance to be provided to students with a foreseeable psychosocial risk is described. This group includes student's with COVID-19, students on exchange programmes or simply away from their families, students with a low socioeconomic status, those with a previous history of mental disorders, including alcohol and drug use, caregivers of people with illness or disability, and residents in rural areas or with children.37 Students who may be grieving following the COVID-19-related death of relatives should be closely monitored and are a group which could become increasingly large at any point in the pandemic.39

Also usually included in this group are health science students who perform care activities in hospitals. For them, it is essential to guarantee the provision of all the necessary personal protective equipment.38 It is also possible that, with the care needs of the general population, some students from other specialities may participate in patient care as volunteers. It could be beneficial if the volunteer programmes were structured or coordinated by the university, so that this vision of vulnerability to symptoms of mental illness is maintained, the overload of responsibilities is avoided and the supervision of their work is guaranteed.

Care for symptoms of mental illnessCounselling centreOne of the most common actions found was the availability of a 24-h counselling centre that can provide round-the-clock mental healthcare by telephone, digitally and even in person (if required).20,26,29,31,37,41 This counselling centre may be responsible for designing and implementing the mental health programme and must keep up to date on the screening and have the necessary response protocols. The aim is to provide psychological support and even clinical psychology and psychiatric care. Many institutions already have a counselling centre, but if not, it can be set up with staff from the university's mental health areas or be independent. Although reference is made to a centre with its own infrastructure, some resources present it as a “functional area” within the institution's own organisation, to highlight that additional resources may not be necessary if there is an organised working group.31 The counselling centre intervention should be as early as possible as, following the experience of previous epidemics and disasters, it seems that early interventions prevent and minimise psychological symptoms.21

CrisesCrisis plans are among the most important actions because crises can be life-threatening. It is recommended that rapid response teams be created to deal with crisis situations, such as severe exacerbation of symptoms, suicidal ideation and behaviour, or domestic violence. These and other areas that are considered potential crisis triggers should be included in training plans so they not only teach about the routes to be activated, but also generate awareness and understanding to help with prevention and mitigation.

GriefPandemic-related death can also happen to people close to the students, so they may experience grief reactions. Crisis intervention and psychological first aid must be considered for a severe acute reaction, but how the grieving process evolves over time also needs to be monitored, as it can affect performance in later academic life.

SuicideUniversity students have reported an increase in suicidal ideation and behaviour,37 so it is essential to implement a protocol to address these issues, either through the results of screening, or in response to a direct request from the student. Detection can also be aided by indirect peer observation; in the “Battle Buddies” programme, indirect evidence from evaluation of the scheme in the military points to a reduction in suicide rates in the army, as the assigned buddy often noticed and sounded the alarm.19 In addition to psychological intervention by telephone or even in person, a suicide risk assessment is required to define the need for hospitalisation, which entails coordination with the health services so that intervention is timely and any progress made by the educational institution is not lost.

Domestic violenceThis can affect students' households. During the lockdown in China, a three-fold increase in domestic violence was detected, while in the United Kingdom there was an increase in the average number of women murdered and the number of calls to emergency services for domestic violence. For this crisis, female, black or ethnic minority students and the LGBT population can be considered a population at risk. This issue should motivate forceful campaigns for prevention and socialisation of care routes through the university's communications platform. Care provision should also include coordination with the judicial system and social organisations to protect the victims, which may include moving them to student residences if the university has them.33 Another form of violence that must be taken into account is cyberbullying, as transition to digital life increases the circulation of sensitive information, which some people, even outside the university, may abuse.

Teaching-related changes with an emphasis on mental healthOnline learningWhether or not there are face-to-face academic activities will depend on the degree of lockdown adopted in each location. It has been suggested that online learning should be prioritised in the hope that students staying at home will help reduce transmission, but that can lead to an increase in academic pressure, which then causes stress. Virtual learning may allow better organisation of time, but it can also blur the boundaries between academic life and other areas of life and end up saturating students. Transition to this learning environment requires training of teachers and students in the use of technologies, as well as the availability of adequate equipment. Virtual environments could be created or used to recreate classrooms, which include means of direct communication between the lecturer and the student.24 Features described for this learning environment include active, interactive learning, with discussion panels and group work, and inclusive learning, in the sense that it is the student who leads and participates in teaching-related decisions.

Content that helps develop skills to use the learning platforms can be included in the curriculum. The content can be built with the students; in fact, if students feel they are included, this can help adaptation and well-being and reduce stress levels.28 However, all this has to be balanced with the possible gaps that prevent some students from having the technology to take part,37 although such issues should have been detected. The existence of gaps or barriers will be the subject of an individual analysis, preventing any repercussions on grades for these reasons to the extent possible.

Fluent communication is paramount. Having clear instructions about academic activities can reduce uncertainty and therefore anxiety, and help the student to manage their time and be able to apply the self-care recommendations. It is recommended that academic councils develop clear and flexible evaluation guides.41

Blended learning can be an option in courses with essential face-to-face activities, such as health care.28 Another option is virtual simulation, in which students are asked to synchronously coordinate and collaborate to treat clinical cases. In the case of placements, internships and research projects, alternatives should be sought to prioritise working from home.

Academic calendarStudent admission and graduation each need to be analysed in their own context. In both processes there must be a transition supported by the educational institution so as to reduce the anxiety these situations can generate. Remedial courses or programmes can be included to offset the possible interruptions that are generated by the pandemic or by individual situations.37 Another proposal was to provide support to recently graduated students, as the socioeconomic conditions deriving from the pandemic may affect their employment prospects, which obviously generates stress. Coordination with private companies and government bodies could be sought so that recent graduates are hired and student loan payments are suspended, at least temporarily.41 Another option found is to facilitate mechanisms for graduates to continue academic life and obtain an additional degree.

In the case of health and social care students, graduation may be urgent, so they can become much needed human resources in healthcare to help with the pandemic. This highlights the need for joint work with the health ministry of each country and the educational and health institutions, as there have to be guarantees that the programme objectives were met and the student meets the standards to practice.38

Mentoring and counsellingLecturers and educators can provide direct advice (via video calls or online group meetings) on study habits, subjects specific to each course and mental health. Teachers can publish virtual office hours to dedicate to students, with the availability and training to address non-academic topics.25 Peer counselling or mentoring can work for some students, as well as being a strategy to consolidate knowledge, according to the maxim “teaching is learning twice”.22

“Beyond the academic”Students should consider implementing strict rules about working hours to help the balance between study, rest and the other spheres of a student's life, including spirituality.24 In some cases, the physical spaces of the university represented the only opportunity for recreational, sports or leisure activities. Depending on how the pandemic develops and, in collaboration with local authorities, spaces could be adapted for the practice of some of these activities.32 The need to plan holiday time in advance and with respect for the thoughts of the students is considered, and this can be helped by providing a preview of the calendar and the setting and meeting of objectives.24

DiscussionThe mental health of students during the COVID-19 pandemic is presented in the literature as a need that must be addressed as a priority by higher education institutions. In this synthesis, we have described actions that have been recommended to support the student in this pandemic. Although no evaluation of the effectiveness of these actions was found and the references included would be classed as descriptive studies, in view of the urgency called for by the pandemic, it is reasonable to consider the implementation of a number of them. We believe that this is a fertile field of research in which, taking advantage of the fact that we are dealing with academic spaces, research could be carried out into the mental health situation and the actions that may have been implemented, in order to bring these issues to the attention of the scientific community and encourage collaborative work.

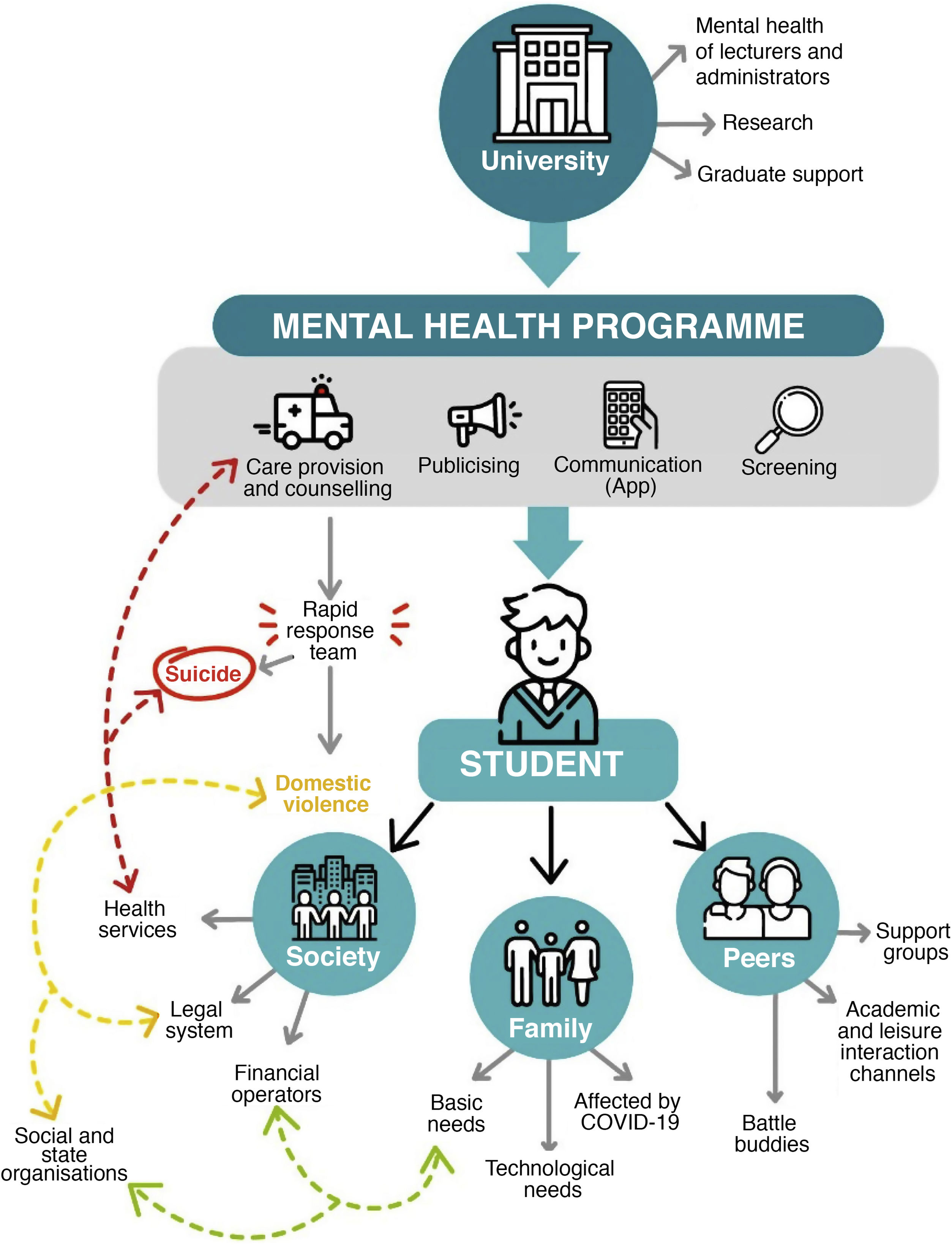

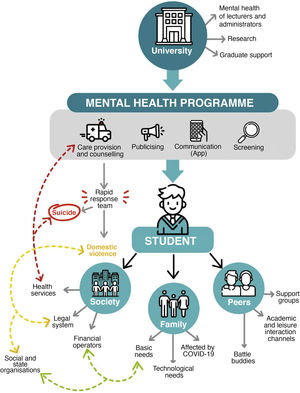

The actions described, which can be included in the mental health programme, involve seeing students within the complex system in which they interact, in addition to the university, with their peers, their family and their community, and where there are different situations that all have an effect on their health. Therefore, it may be useful to apply an ecosystem conceptual framework to put them in context and be able to see the multiple interactions that occur in the student's environment (Fig. 2). Ecosystems can be understood as dynamic groups of actors found in a common space and time, organised in hierarchies according to their interactions.42 In the field of health, all the circumstances and actors that are related to a health phenomenon are referred to from a nano level (in this case, student-lecturer and peers), micro level (university, family), meso level (the community) and macro level (region and country). In mental health, this separation seeks to direct the strength of social, human and physical capital at these levels and their connections to meet the needs of a population at risk of mental disorders.43

Actions for the mental health of university students. The conceptual model of the ecosystem that takes into account the student's interactions with their family, classmates and the rest of society is highlighted. Important among the recommended actions is the creation of a specific programme by the university that specifically addresses the mental health of students and encompasses the different focuses. The programme should have resources to screen symptoms, but also unmet basic and technological needs. It is therefore necessary to coordinate with other bodies. There must also be mechanisms for crisis situations, such as suicide and domestic violence. This highlights the importance of the essential connection with health services and other potentially helpful actors. Source: created by the authors.

At the nano level, the student's interaction with their lecturer becomes an opportunity to detect symptoms, as direct and continuous contact in academic activities allows the student's performance to be monitored.44 Although not specifically found in the literature, this opportunity requires lecturer training to increase knowledge and skills, as it is necessary to be familiar with the subject of mental health, which may not occur spontaneously.45 It is worth noting that the mental health of lecturers should also be of interest to universities, as it can have a direct impact on students.46 Peer support is invaluable, which is why it was frequently identified in the sources reviewed. Even in a virtual environment, sharing the experience with a peer seems to reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms, in part because of the sense of connection and belonging and the learning that can come from the peer's experience.47–49

At a micro level, the university institution as such is the command centre for the interventions described. It is the university that produces the guidelines on which the curriculum, academic requirements, institutional climate and administration of resources depend.50 For that reason, the agreement of those who administer it is the prerequisite for any action. With regard to the family, it should be noted that the events that stress the family nucleus will have an impact on the student's mental health and that the basic and technological needs that are experienced at home will directly affect the student's quality of life, including their stay at university.51 That is why the participation of social, state and financial operators is necessary, as university resources would not be sufficient. At the home level, the detection of and timely intervention in dealing with the domestic violence that has continued to occur during the pandemic in Colombia is essential.52 The university can be the way in, and a care pathway must be planned to continue with the intervention of other additional actors, such as the judicial system and the health services. Here, the meso and macro levels determine how the care will continue in individual cases, as well as how many of the needs detected by the university may be resolved. In the case of suicidal behaviour, for example, coordination with health services is necessary to provide the clinical care that may be needed after early detection. We think that SARS-CoV-2 should be seen as “a species” that entered the ecosystem and could be here to stay long-term. To that extent, mental health problems will persist, so actions must be designed to be long-lasting, without delegating all responsibility to the university.

One of the strengths of this synthesis is the exhaustive search that enabled purposeful sampling of information. Nevertheless, we need to point out as a limitation that the evidence was not qualified, as we were only able to include descriptive studies and expert recommendations. From a critical-scientific point of view, the evidence would be classified as low quality, which may mean that the benefit of some recommendations may be overestimated. That is only to be expected since research on the pandemic began so recently. This synthesis should therefore be seen as a description of actions that can be analysed by the different players at universities when planning their interventions in mental health.

ConclusionsThe resources consulted propose that universities create programmes that specifically address the mental health of students and that encompass the promotion of mental health and prevention of symptoms of mental illness, with psychoeducation, screening of symptoms and needs, and promotion of social interactions, including peer support. Care and treatment of symptoms and the implementation of rapid response systems for crises, such as suicidal behaviour and domestic violence, should also be provided. Teaching strategies should be designed to reduce stress, but also taking into account the need to adhere to lockdown measures due to the pandemic. However, further research is required on how the mental health situation evolves and the effect of the actions that are being taken now.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Zapata-Ospina JP, Patiño-Lugo DF, Marcela Vélez C, Campos-Ortiz S, Madrid-Martínez P, Pemberthy-Quintero S, et al. Intervenciones para la salud mental de estudiantes universitarios durante la pandemia por COVID-19: una síntesis crítica de la literatura. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:199–213.