The COVID-19 pandemic is having an impact on multiple levels, one being the way of providing mental health care services. A study was proposed in order to identify the standpoints regarding the role we must assume as psychiatrists in the setting of this pandemic in Colombia.

MethodsA study was developed employing a Delphi-type methodology. Three types of psychiatrist were included for the application of the instrument: directors of academic psychiatry programmes, directors of mental health institutions and private practitioners.

ResultsResponses were collected over the course of a month (between April and May) by 24 participants corresponding to 14 private practitioners (58.3%), 6 heads of academic programmes (25.1%) and 4 directors of mental health services (16.6%). The results, grouped around the psychiatric work, describe the impact generated by the pandemic and the possible role of the specialist.

ConclusionsConsistency was identified around the need to provide a differential approach according to the vulnerabilities of each group of people exposed to the pandemic; as well as the remote provision of health care through technology, often using videoconferencing.

La pandemia de COVID-19 genera impactos en múltiples niveles, uno de ellos es la forma de prestar servicios de atención en salud mental. Este estudio se planteó con el fin de identificar las posturas sobre el rol que debemos asumir como psiquiatras en el marco de la pandemia de COVID-19 en Colombia.

MétodosSe desarrolló un estudio mediante metodología tipo Delphi. Para la aplicación del instrumento, se incluyeron 3 tipos de participantes: psiquiatras directores de programas académicos de psiquiatría, psiquiatras directores de instituciones de salud mental y psiquiatras que ejercieran su labor clínica fuera del contexto académico.

ResultadosRecolectaron las respuestas en el transcurso de 1 mes (entre abril y mayo) 24 participantes: 14 psiquiatras clínicos (58,3%), 6 directores de residencia (25,1%) y 4 coordinadores de servicios de salud mental (16,6%). Se describen los resultados agrupados en torno al quehacer psiquiátrico, el impacto generado por la pandemia y el posible rol del especialista.

ConclusionesSe identificó consistencia en torno a la necesidad de brindar un abordaje diferencial acorde con las vulnerabilidades propias de cada grupo de personas expuestas a la pandemia, así como la implementación de estrategias de atención psiquiátrica a distancia.

The direct impact of COVID-19 on physical health, the public health measures necessary for controlling the infection (involving quarantine, closures and social distancing) and the financial consequences have had a negative effect on the emotional health of individuals and whole populations. The accumulated evidence after a year of the pandemic shows that 25%–40% of the population has had sleep problems, stress, anxiety or depression, with these particularly affecting patients who have had the disease, healthcare workers and people with mental illness.1–3

The pressure the pandemic has put on healthcare systems has led to the implementation of strategies to mitigate its effects in the medium and long term. Among other intersectoral interventions, it has been necessary to join forces to maintain the continuity of care for users, contain outbreaks of the infection in hospitals and facilitate access for the most vulnerable people.3–5 Action involving psychiatry and mental health specialists is being taken on multiple fronts, such as instructing on adverse psychological events and their consequences, promoting healthy behaviours, reinforcing the importance of mental health in care systems, facilitating problem solving, empowering patients, families and healthcare providers to reduce fears and uncertainty and promoting self-care from the healthcare providers.6,7

Another line of action is in the care of people with a history of mental illness, which needs to focus on minimising the risks of relapse, preventing admission to hospitals, where social distancing is more difficult to achieve, and being aware of interactions between psychotropic drugs and the medications indicated in the event of becoming seriously ill with COVID-19.5 Another area which must not be neglected is that of the direct psychosocial consequences in patients infected by the virus, ranging from behavioural disorders to confusional states.7

Given the need to keep face-to-face contact to a minimum in both mental health and clinical research, this pandemic has forced healthcare to rapidly shift to the use of virtual platforms. The urgency with which this change was introduced meant physicians, patients, institutions and insurers were faced with innumerable challenges. Not surprisingly, although psychiatry was one of the areas of medicine with the most experience in this field, the transition from face-to-face care to telemedicine has not been without its obstacles.8–10

In this context, the aim of this study was to identify the different stances on the role, as psychiatrists, we should be adopting in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in Colombia.

MethodsWe used the Delphi method with a pre-designed form with questions about psychiatric work, the impact caused by the pandemic and the possible role of the specialist in the light of such challenges. Three types of participants were selected to respond: psychiatrists who were directors of academic psychiatry programmes; psychiatrists who were directors of mental health institutions; and psychiatrists who worked in clinical practice, preferably in cities where there were no psychiatry specialisation programmes.

An evaluation was carried out in two rounds. The first consisted of a survey of five open questions about the specialist's perspective of society's expectations regarding their role; expectations as specialists in our ability to provide help; doubts about the ability to carry out our professional work; the impact of the pandemic on the continuity of psychiatric treatment and the quality of mental health care; and possible changes in the provision of services during the pandemic. In view of the diverse nature of the responses in this first round and with the hope of obtaining greater consensus, a second series of closed questions was sent to the same psychiatrists who took part in the first round.

The questionnaires were designed on the Google Forms platform and sent out by email to all the potential study participants. Three of the authors categorised the responses to the first round of questions to later define the closed questions from which the consensus would be evaluated. Once the information was collected, the responses were tabulated and downloaded into Microsoft Excel files for further analysis.

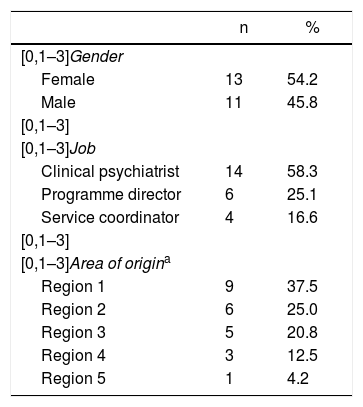

ResultsThe survey was sent to the directors of the 16 post-graduate programmes in Psychiatry in Colombia and to 32 additional specialists (both administrative and clinical). The characteristics of the participants included are shown in Table 1. In April and May 2020, responses were collected from 24 participants: 14 clinical psychiatrists (58.3%); six residency programme directors (25.1%); and four mental health service coordinators (16.6%). Although uniform representation from all the regions of Colombia was sought, 37.5% of the participants came from Bogotá; 25% from Antioquia and the coffee region; 20.8% from Cali and Neiva, and the remaining 16.7% from Bucaramanga, the Eastern Plains and the Caribbean. The female-to-male ratio was 1:1.

Participant characteristics.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| [0,1–3]Gender | ||

| Female | 13 | 54.2 |

| Male | 11 | 45.8 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Job | ||

| Clinical psychiatrist | 14 | 58.3 |

| Programme director | 6 | 25.1 |

| Service coordinator | 4 | 16.6 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Area of origina | ||

| Region 1 | 9 | 37.5 |

| Region 2 | 6 | 25.0 |

| Region 3 | 5 | 20.8 |

| Region 4 | 3 | 12.5 |

| Region 5 | 1 | 4.2 |

According to the territorial division of the Asociación Colombiana de Psiquiatría [Colombian Association of Psychiatry]. Region 1: Bogotá and Cundinamarca; Region 2: Antioquia, Caldas, Risaralda, Quindío and Chocó; Region 3: Valle, Cauca, Nariño, Tolima and Huila; Region 4: Boyacá, Santander del Norte, Santander, Meta, Arauca, Casanare, Vichada, Guaviare, Guainía, Vaupés, Amazonas, Putumayo and Caquetá; Region 5: Atlántico, Bolívar, Magdalena, Sucre, Córdoba, Cesar, Guajira and San Andrés.

With regard to society's expectations of the role of the psychiatrist, the options for which the greatest agreement was obtained were: developing care programmes for mental disorders for patients with previous diagnoses adapted to the circumstances of the pandemic (81%); providing emotional support for the general population in terms of coping with the stressors of the pandemic (71.5%); designing mental healthcare programmes for special populations such as children and adolescents and healthcare workers (66.7%); and implementing promotion and prevention strategies in mental health for the population as a whole in the midst of the pandemic (61.9%).

In response to the question, “What can we do to help the general population and people with established mental illness?”, there was greatest consensus on: increasing our knowledge and expertise in dealing with emotional responses to the disaster, with a differential approach according to degree of vulnerability (95.2%); providing emotional support and promoting resilience with the support of virtual platforms and telemedicine strategies (90%); screening the population and assessing symptoms in order to generate evidence-based strategies (76.2%); and managing the mobilisation of institutional resources to ensure clinical care (47.6%).

With regard to uncertainties or concerns about the ability to practice professionally, there was agreement on the fear of the looming economic and social crisis (71.4%) and the challenge of implementing and delivering virtual care compared to face-to-face care (47.7%). Interestingly, just over half of the respondents did not report uncertainties or concerns about the ability to practice professionally (52.4%), around a quarter expressed concern about not having adequate or sufficient protective equipment for face-to-face patient care (23.3%) and a minority reported a feeling of powerlessness and insufficient coping capacity among psychiatrists (19%).

For the consequences of the pandemic on direct patient care, the responses were broadly distributed in two groups. The first, relating to the continuity of treatment (pharmacological and psychotherapeutic), with the consequent increase in relapses and use of hospital services, and possible increase in the risk of transmission, showing most agreement in the following statements: possibility of loss of continuity of treatment (76.2%); limitation in the supply of psychotropic drugs (66.7%); and failure to attend outpatient appointments for fear of infection (66.7%). It should be noted that 33% of those surveyed did not perceive any type of concerns about the continuity of treatment. The second group was related to the impact of changes due to the current health situation on the quality of mental healthcare during and after the pandemic, with responses that included pessimistic stances (the quality of the doctor-patient bond will be affected by telemedicine, 62%; quality will deteriorate due to the high demand for mental health services and the lack of resources to provide it, 42.8%), in contrast to other more positive outlooks (quality will not be affected as long as policies are established to respond to the needs of patients and their families, 57.2%; quality will be maintained through telemedicine and the coverage of mental health services will be expanded in remote regions of the country, 47.6%).

In contrast to the 23.8% of the participants who considered that the provision of psychiatric services would not vary after the pandemic, with respect to the last question, there was more agreement that the use of virtual channels will increase and that access will be provided to more people (71.5%), teleconsultation will increase but there will be no major changes in face-to-face care (57.1%) and the use of virtual channels will increase, better access for the population will be provided and their rights will be better protected (52.3%).

For more comfortable reading, the different responses have been compiled in graph form with their proportion of agreement, and they are available as additional material.

DiscussionAn increase in mental health problems has been identified during this particular period,11,12 which is sufficient reason to seek to provide proper care for the general population and continuity in the provision of professional services to those who were already attending psychiatric clinics. The findings of this study identify the perceived importance of the role of the psychiatrist during the pandemic, and the concerns about continuity of care and the challenges this health situation is imposing on all actors in the healthcare system. This perception has been corroborated with the increased demand for mental health services worldwide, as well as with the alteration of some mental health service delivery devices.13 In fact, only a small proportion of the psychiatrists considered that there would be no changes of major impact in the routine work of our profession.

An optimal public health response during a pandemic involves reducing the burden of associated symptoms of mental ill-health (psychological trauma, burnout, mental disorders themselves) and preventing the interruption of treatment for chronic conditions, in order to improve the response capacity of healthcare systems and mitigate the global impact of the disease.13 Consequently, a sustainable adaptation of the provision of mental health services should be promoted, identifying at an early stage the most effective strategies for each particular community, and carrying out frequent evaluations of expectations, both in the general population and among mental health workers.13 The pandemic should therefore be seen as an opportunity to make care systems more flexible, promoting the creation of adequate infrastructures for the early care of vulnerable people and reducing access barriers through the use of new technologies.3,8,10

The responses collected showed consistency around the need to provide a differential approach according to the vulnerabilities of each group of people exposed to the pandemic: healthcare workers; patients with COVID-19 and their families; and people with mental illness, users of psychoactive substances or people at risk of suicide.14 This proposal is in line with the increasingly documented notion of COVID-19 as a syndemic, a phenomenon that goes beyond the disease itself and takes into account the interactions between social determinants, varying degrees of exposure and underlying medical comorbidities, both in the expression of symptoms, and in the treatment and prognosis of the disease.15 In other words, the individual experience of this global pandemic is not homogeneous, but rather is criss-crossed by individual vulnerabilities imposed by each community context.16 There is therefore a great need for a differential approach to caring for older people, children, caregivers, healthcare workers, people with pre-existing mental disorders and victims of domestic violence or armed conflict.

The impact of measures to control the pandemic (such as quarantine) on social dynamics and the economy can also become a source of clinically significant stress. Latin America is particularly vulnerable to the economic impact of the pandemic due to the high degree of informality of the workforce, inequity, fragile healthcare systems and the living conditions of a large part of the population, and this requires effective state-level actions that combine economic, social and health policies.17 Not surprisingly, there have already been reports of several suicides related to the economic recession, in addition to the fear of infection itself.18–20 Our participants highlighted that, in addition to promoting optimal care for mental problems and disorders, the commitment of all the actors involved in the healthcare system is essential to ensure continuity in the provision of services and the supply of psychotropic drugs.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health has forced health services around the world to make adjustments, including new forms of interaction in the doctor-patient relationship.21 Despite a structured legal framework (updated in the light of the contingency plans for the pandemic) and previous reports of successful telepsychiatry programmes in Colombia,22,23 the use of new technologies in psychiatrists' clinics was far from common. In the absence of a good internet connection for video consultations, in some cases the only viable option has been the telephone consultation, more accessible but with limitations for the therapeutic relationship.24 Nevertheless, the increase in remote psychiatric care strategies could become a starting point for their implementation in areas where it has been marginal to date,25 making an initial challenge26 a real opportunity for reducing barriers to mental healthcare.

Very few psychiatrists reported feelings of helplessness or powerlessness. It is possible that this finding is related to the very process of training specialists, which includes an awareness of basic elements of managing uncertainty, aimed at promoting and accepting challenging situations, keeping in mind the generation of hope, with a different and holistic form of treatment.27 When these elements fail, however, the specialist may develop a feeling of insufficient coping capacity. It is therefore essential to ensure an adequate support network among colleagues, intervention strategies and care for the “caregiver”, in addition to them being attentive to their own mental health, and knowing when it is time to ask for help.28

One of the limitations of this study is that the response rate was lower than expected and it was not possible to carry out a study which included the stance of all specialists. Moreover, this project only took into account the opinions of the specialists, leaving aside interventions of other players involved, such as patients and relatives. However, we believe that this exercise can serve as a starting point for establishing clear objectives that help us to respond to the psychosocial challenges imposed by this pandemic.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Cano JF, González-Díaz JM, Vallejo-Silva A, Alzate-García M, Córdoba-Rojas RN. El rol del psiquiatra colombiano en medio de la pandemia de COVID-19. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:184–188.